Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees: The Role of Affective Commitment and Person-job Fit

Abstract

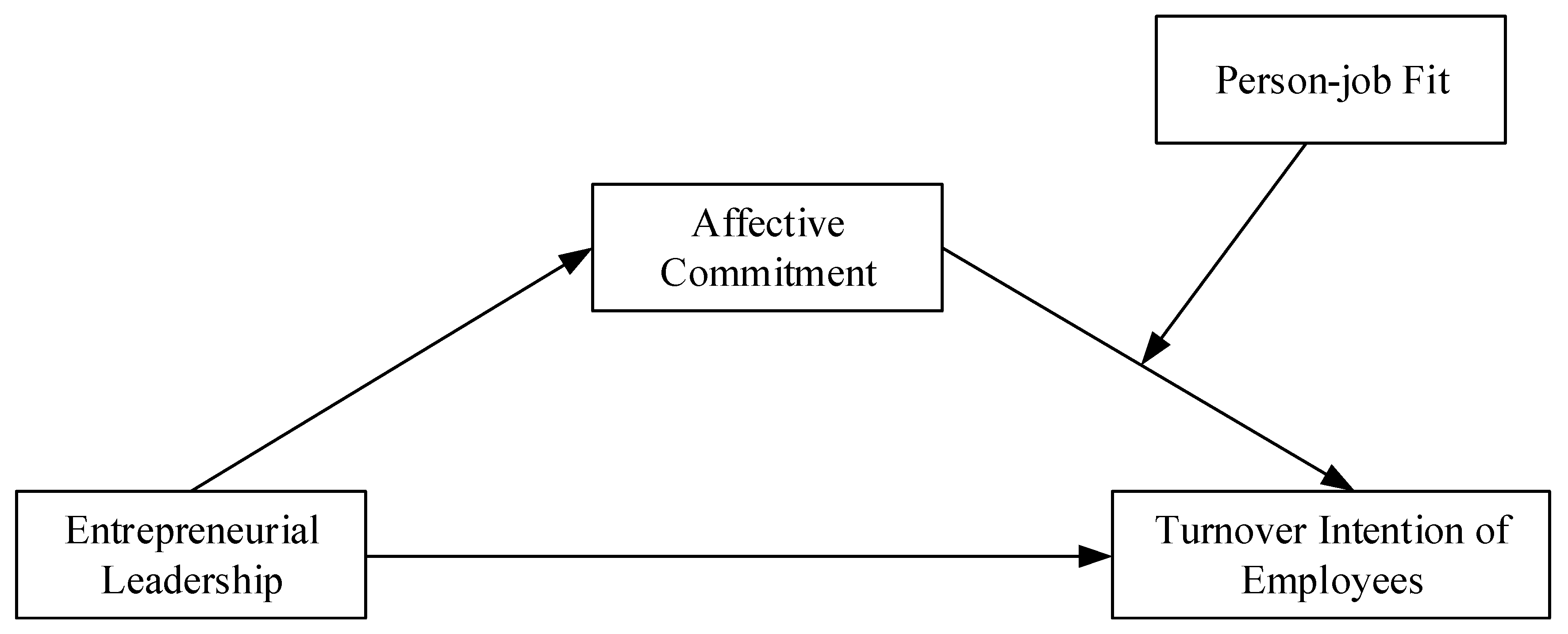

1. Introduction

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. Entrepreneurial Leadership

2.2. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees

2.3. Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

2.4. Moderating Role of Person-job Fit

3. Method

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

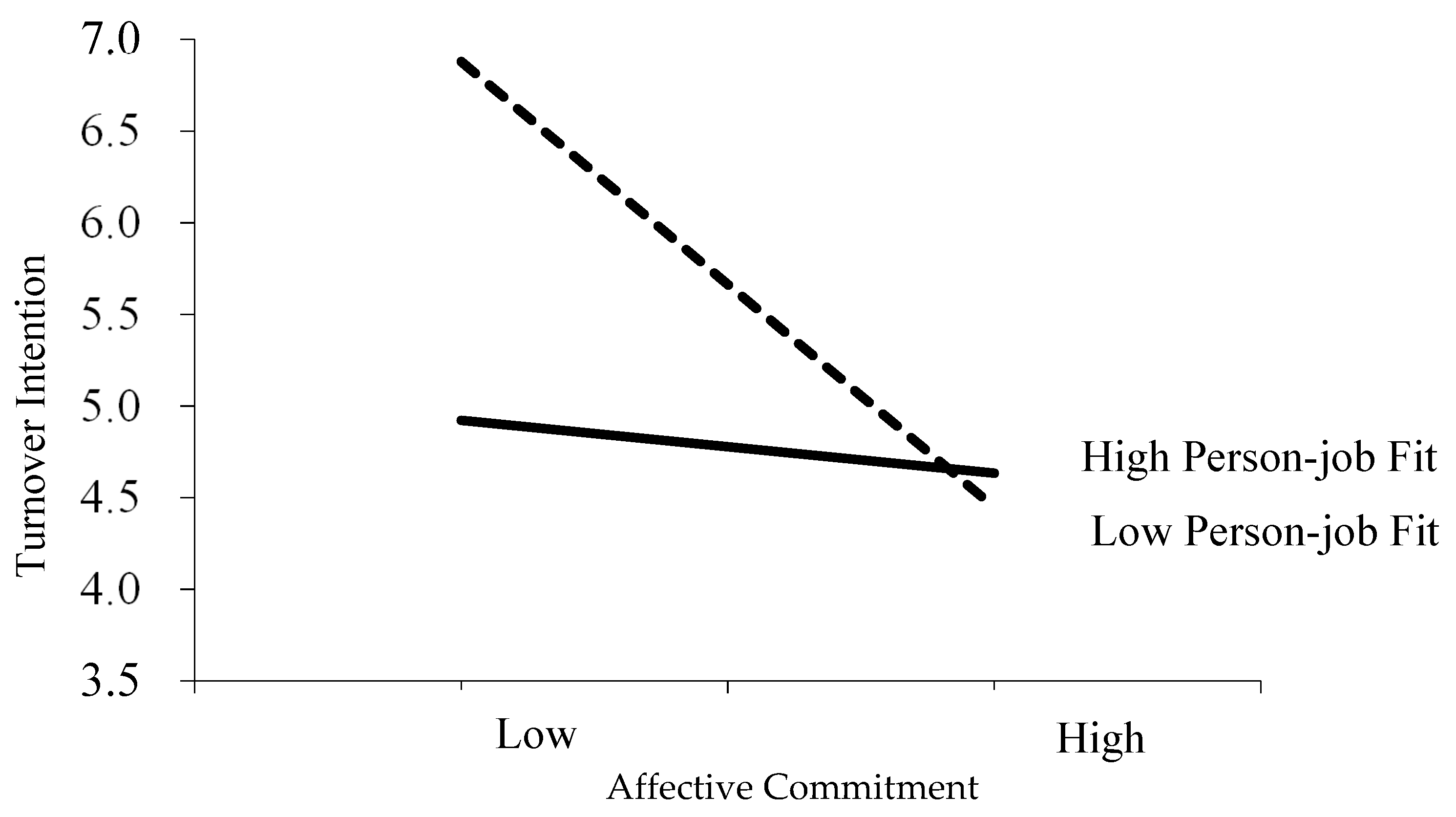

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limits and Prospects

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Adapted Scale of Construct.

| Construct | Scale reference | Adapted scale | Notes |

| Entrepreneurial leadership | Huang et al. (2014) | Leaders prefer to set high standards for business performance | Deleted |

| Leaders pursue continuous business performance improvement | Deleted | ||

| Leaders adjust goals according to employee ability | Deleted | ||

| Leaders draft long-term strategic goals of the company with the premise of understanding the market | Deleted | ||

| Leaders are prone to set challenging goals | Deleted | ||

| Leaders have concrete planning for future development to reduce uncertainty in the process | |||

| Leaders have strong predictability and control over the development prospect of the company | |||

| Leaders voluntarily and actively take the business risks to reduce uncertainty for employees in work | |||

| Leaders reduce uncertainty by various means to establish employee’s confidence in accomplishing the tasks | |||

| Leaders try to reduce the negative responses employees have during business transformation, such as the fear of uncertainty and concerns of failure, to the greatest extent | |||

| Leaders often communicate with employees regarding future development to reduce employee aversion to business transformation | |||

| Leaders have strong persuasiveness and can easily convince others and gain support | |||

| Leaders anticipate and eliminate both explicit and implicit entrepreneurial and managerial barriers | Deleted | ||

| Leaders obtain supportive resources for business transformation and innovation both within and outside the company | Deleted | ||

| Leaders often provide employees with support and help to reduce barriers in work | |||

| Leaders actively establish an atmosphere of innovation | |||

| 1. Leaders strive for employee appreciation of business innovation and transformation. | |||

| Leaders often encourage employees to realize individual values via work | |||

| Leaders actively structure work teams to facilitate employee cooperation | |||

| Leaders can inspire employees to accomplish the business goals | |||

| Leaders have a clear understanding of the business scope, what to do and what not to do | Deleted | ||

| Leaders clearly define the limits of company ability and avoid unnecessary resource consumption | Deleted | ||

| Leaders are good at integrating human and material resources to carry out the work within the company capacity | |||

| Leaders have strong confidence in employees accomplishing fixed tasks | |||

| Leaders often encourage employees to innovate | |||

| Leaders make quick and effective operational decisions according to company capacity and resources | |||

| Turnover intention | Liang (1999) | I often want to leave this company | |

| I’m highly likely to find a new job next year | |||

| I often want to change my job recently | |||

| Affective commitment | Yao et al. (2008) | I’m glad to work in this company | |

| I am a part of this company | |||

| I feel a sense of belonging in this company | |||

| I have a great affection for this company | |||

| Person-job fit | Weng and McElory (2010) | I think this job fits me very well | |

| I’m equipped with necessary experience, skills and knowledge for this job | |||

| Current work condition fits my demands | |||

| My personality fits this job well |

References

- Amway Global Entrepreneurship Report, AGER, 2018. Available online: https://www.amwayglobal.com/amway-global-entrepreneurship-report (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Separation and Compensation Reports of 2017, 51job. Available online: http://research.51job.com/insight−396.html (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Yang, J. Research on Servant Leadership’s Influences on Employee Turnover and Creativity. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Q.; Wang, T.; Wu, S.; Hu, H. Affective leadership: Scale development and its relationship with employees’ turnover intentions and voice behaviour. Foreign Econ. Manag. 2016, 38, 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, G.; Zhao, Y. Ethical leadership and employees’ turnover intention: Leader-member exchange as a mediator. Sci. Sci. Manag. S. T. 2017, 38, 160–171. [Google Scholar]

- Hensenl, R.; Visser, R. Shared leadership in entrepreneurial teams: The impact of personality. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2018, 24, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, J.; Bhau, S. Impact of transformational leadership on job performance: Mediating role of leader–member exchange and relational identification. Sage Open 2015, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanza, G.; Moriano, J.A.; Molero, F.; Lévy Mangin, J.P. The effects of authentic leadership on turnover intention. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2015, 36, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaech, S.; Baldegger, U. Leadership in start-ups. Int. Small Bus. J. 2017, 35, 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renko, M.; El Tarabishy, A.; Carsrud, A.L.; Brännback, M. Understanding and measuring entrepreneurial leadership style. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabishy, A.; Solomon, G.; Fernald, L.W.; Sashkin, M. The entrepreneurial leader’s impact on the organization’s performance in dynamic markets. J. Priv. Equity 2005, 8, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; MacMillan, I.C.; Surie, G. Entrepreneurial leadership: Developing and measuring a cross-cultural construct. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitch, C.; Hazlett, S.A.; Pittaway, L. Entrepreneurship education and context. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2012, 24, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldegger, U.; Gast, J. On the emergence of leadership in new ventures. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2016, 22, 933–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.G.; MacMillan, I.C. The Entrepreneurial Mindset: Strategies for Continuously Creating Opportunity in an Age of Uncertainty; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; Volume 284. [Google Scholar]

- Hejazi, S.A.M.; Malei, M.M.; Naeiji, M.J. Designing a scale for measuring entrepreneurial leadership in SMEs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics Marketing and Management (IPEDR), Singapore, 26–28 February 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Harnessing personal energy: How companies can inspire employees. Organ. Dyn. 1987, 16, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R.P. Entrepreneurship and leadership: Common trends and common threads. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2003, 13, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, J.M. Using founder status, age of firm, and company growth rate as the basis for distinguishing entrepreneurs from managers of smaller business. J. Bus. Ventur. 1995, 10, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, W.H., Jr.; Watson, W.E.; Carland, J.C.; Carland, J.W. A proclivity for entrepreneurship: A comparison of entrepreneurs, all business owners, and corporate manager. J. Bus. Ventur. 1999, 14, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, N.; Yang, J. A unified model of entrepreneurship dynamics. J. Financ. Econ. 2012, 106, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B.J.; Bass, B.M. Individual consideration viewed at multiple levels of analysis: A multi-level framework for examining the diffusion of transformational leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1995, 6, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, B.S.; Eastman, K.K. The nature and implications of contextual influences on transformational leadership: A conceptual examination. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 80–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B.; Howell, J.M. Organizational and contextual influences on the emergence and effectiveness of charismatic leadership. Leadersh. Q. 1999, 10, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Comparative analysis on multiple mediating effects in impact of entrepreneurial leadership on employee′s innovative behaviour. Technol. Econ. 2015, 10, 29–33, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Devarajan, T.P.; Ramachandran, K.; Ramnarayan, S. Entrepreneurial leadership and thriving innovation activity. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Global Business & Economic Development, Bangkok, Thailand, 8–11 January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hmieleski, K.M.; Ensley, M.D. A contextual examination of new venture performance: Entrepreneur leadership behaviour, top management team heterogeneity, and environmental dynamism. J. Organ. Behav. 2007, 28, 865–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Wu, W. Influence of entrepreneurial leadership on employee’s organizational commitment and job satisfaction: Considering mediating role of emotional intelligence. Technol. Econ. 2014, 33, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y.H.; Jaw, B.S. Entrepreneurial leadership, human capital management, and global competitiveness: An empirical study of Taiwanese MNCs. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2011, 2, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.; Thorpe, R. Not another study of great leaders: Entrepreneurial leadership in a mid-sized family firm for its further growth and development. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2010, 16, 457–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansikas, J.; Laakkonen, A.; Sarpo, V.; Kontinen, T. Entrepreneurial leadership and familiness as resources for strategic entrepreneurship. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2012, 18, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, H.; Ford, J. Discourses of entrepreneurial leadership: Exposing myths and exploring new approaches. Int. Small Bus. J. 2016, 35, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.; Leitch, C.; McAdam, M. Breaking glass: Toward a gendered analysis of entrepreneurial leadership. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2015, 53, 693–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Yang, S.; Liu, D. The influence of professional identity, job satisfaction, and work engagement on turnover intention among township health inspectors in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobley, W.H. Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, R.M.; Mowday, R.M. Employee Turnover and Post Decision Accommodation Processes. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Management University of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.L. The Study of Turnover; Iowa State University Press: Amen, IA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 51–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.R.; Lee, T.W. The unfolding model of voluntary turnover and job embeddedness: Foundations for a comprehensive theory of attachment. Res. Organ. Behav. 2001, 23, 189–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, I.; Jeung, C.W. Uncovering the Turnover Intention of Proactive Employees: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement and the Moderated Mediating Role of Job Autonomy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bothma, C.F.; Roodt, G. The validation of the turnover intention scale. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyensare, M.A.; Anku-Tsede, O.; Sanda, M.A.; Okpoti, C.A. Transformational leadership and employee turnover intention: The mediating role of affective commitment. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 12, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirtas, O.; Akdogan, A.A. The effect of ethical leadership behavior on ethical climate, turnover intention, and affective commitment. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 130, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee-Organization Linkages: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T.A.; Meyer, J.P.; Wang, X.H. Leadership, commitment, and culture: A meta-analysis. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2013, 20, 84–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perryer, C.; Jordan, C.; Firns, I.; Travaglione, A. Predicting turnover intentions: The interactive effects of organizational commitment and perceived organizational support. Manag. Res. Rev. 2010, 33, 911–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joarder, M.H.R.; Sharif, M.Y.; Ahmmed, K. Mediating role of affective commitment in HRM practices and turnover intention relationship: A study in a developing context. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 2, 135–158. [Google Scholar]

- A’Yuninnisa, R.N.; Saptoto, R. The effects of pay satisfaction and affective commitment on turnover intention. Int. J. Res. Stud. Psychol. 2015, 4, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slugoski, E.V. Employee Retention: Demographic Comparisons of Job Embeddedness, Job Alternatives, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment. Master’s Thesis, University of Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R. Person-Job Fit: A Conceptual Integration, Literature Review, and Methodological Critique; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 283–357. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Xin, X.; Bai, G. Hierarchical plateau and turnover intention of employees at the career establishment stage: Examining mediation and moderation effects. Career Dev. Int. 2016, 21, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scroggins, W.A. The relationship between employee fit perceptions, job performance, and retention: Implications of perceived fit. Empl. Responsib. Rights J. 2008, 20, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmojo, M. The influence of transformational leadership on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and employee performance. Int. Res. J. Bus. Stud. 2015, 5, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verquer, M.L.; Beehr, T.A.; Wagner, S.H. A meta-analysis of relations between person–organization fit and work attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof, A.L. Person-organization fit: An integrative review of its conceptualizations, measurement, and implications. Pers. Psychol. 1996, 49, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, P.; Zarutskie, R. Who works for startups? The relation between firm age, employee age, and growth. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 112, 386–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topel, R.; Ward, M. Job mobility and the careers of young men. Q. J. Econ. 1992, 107, 441–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.L.; Ding, D.H.; Chen, Z. Entrepreneurial leadership and performance in Chinese new ventures: A moderated mediation model of exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation and environmental dynamism. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2014, 23, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, K. Fairness in Chinese Organizations. Unpublished Dissertation, Old Dominion University, Norfolk, VA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Huang, W.B.; Fan, X.C. Study on employee loyalty in service industry based on organizational commitment mechanism. Manag. World 2008, 5, 102–114. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, N.J.; Meyer, J.P. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J. Occup. Psychol. 1990, 63, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.W.; Price, J.L.; Mueller, C.W. Assessment of Meyer and Allen’s three-component model of organizational commitment in South Korea. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.; McElroy, J.C. Vocational self-concept crystallization as a mediator of the relationship between career self-management and job decision effectiveness. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 234–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Greenhaus, J.H. The relation between career decision-making strategies and person–job fit: A study of job changers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2004, 64, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffeth, R.W.; Hom, P.W.; Gaertner, S. A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. J. Manag. 2000, 26, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Gao, F.; Wang, F. An improved independent component regression modelling and quantitative calibration procedure. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 1519–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.; Judd, C.M.; Yzerbyt, V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Singapore, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.; Cohen, P.; West, S.G.; Aiken, L.S. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioural Sciences, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: Toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 86, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Employee Effectiveness: From the Perspective of Fit and Human Resource Practices. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alniaçik, E.; Alniaçik, Ü.; Erat, S.; Akçin, K. Does person-organization fit moderate the effects of affective commitment and job satisfaction on turnover intentions? Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.J.; Kristof-Brown, A.L. Toward a multidimensional theory of person-environment fit. J. Manag. Issues 2006, 18, 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, H.S.; Kee, D.M.H. The core competence of successful owner-managed SMEs. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor | 689.87 | 344 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.05 | 813.87 |

| Three-factor | 745.90 | 347 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.05 | 863.90 |

| Two-factor | 948.43 | 349 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.06 | 1063.43 |

| Single-factor | 1474.62 | 350 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.09 | 1586.62 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Employee Age | ||||||||

| 2 Monthly Salary | 0.29 ** | |||||||

| 3 Number of Employees | 0.15 ** | 0.29 ** | ||||||

| 4 Corporate Tenure | 0.41 ** | 0.31 ** | 0.32 ** | |||||

| 5 Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0.11 * | 0.20 ** | 0.12 * | 0.23 ** | ||||

| 6 Affective Commitment | 0.14 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.64 ** | |||

| 7 Turnover Intention | −0.18 ** | −0.29 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.50 ** | −0.69 ** | ||

| 8 Person-job Fit | 0.21 ** | 0.25 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.56 ** | 0.68 ** | −0.59 ** | |

| Mean | 2.26 | 2.91 | 2.72 | 2.67 | 5.21 | 5.10 | 2.98 | 5.22 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.07 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.74 | 1.24 | 1.51 | 1.03 |

| Affective Commitment | Turnover Intention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | |

| Control Variables | ||||||||

| Age | 0.15 ** | 0.07 | –0.22 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.10 ** |

| Monthly Salary | 0.06 | 0.05 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Number of Employees | 0.31 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Corporate Tenure | −0.04 ** | −0.03 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.06 |

| Independent Variable | ||||||||

| Entrepreneurial Leadership | 0.58 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.11 * | −0.12 ** | |||

| Mediating Variable | ||||||||

| Affective Commitment | −0.66 ** | −0.57 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.79 ** | ||||

| Moderating Variable | ||||||||

| Person-job Fit | −0.19 ** | −0.43 ** | ||||||

| Interaction | ||||||||

| Affective Commitment × Person-job Fit | 0.52 * | |||||||

| R2 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.53 | 0.53 |

| F-value | 18.76 ** | 71.51 ** | 14.73 ** | 42.06 ** | 82.46 ** | 72.23 ** | 66.10 ** | 58.82 ** |

| △R2 | 0.15 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| △F | 18.76 ** | 240.05 ** | 14.73 ** | 132.96 ** | 310.19 ** | 149.11 ** | 14.92 ** | 4.26 * |

| b | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | −0.69 | 0.07 | [−0.84, −0.55] |

| Direct Effect | −0.29 | 0.08 | [0.00, −0.45] |

| Mediator | Conditional indirect effects of person-job fit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | b | SE | Bootstrap 95% CI | |

| Affective commitment | Low | −0.61 | 0.08 | [−0.78, −0.45] |

| Middle | −0.53 | 0.08 | [−0.70, −0.37] | |

| High | −0.45 | 0.10 | [−0.64, −0.26] | |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, J.; Pu, B.; Guan, Z. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees: The Role of Affective Commitment and Person-job Fit. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132380

Yang J, Pu B, Guan Z. Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees: The Role of Affective Commitment and Person-job Fit. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(13):2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132380

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Juan, Bo Pu, and Zhenzhong Guan. 2019. "Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees: The Role of Affective Commitment and Person-job Fit" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 13: 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132380

APA StyleYang, J., Pu, B., & Guan, Z. (2019). Entrepreneurial Leadership and Turnover Intention of Employees: The Role of Affective Commitment and Person-job Fit. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(13), 2380. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132380