Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framing

2.1. Use of Personas and Behavioural Archetypes in User Experience (UX) Design

2.2. Personas and Sociability

2.3. Developing Behavioural Archetypes for People with Problematic Online Attachment

2.4. Personality in Problematic Attachment on Social Media

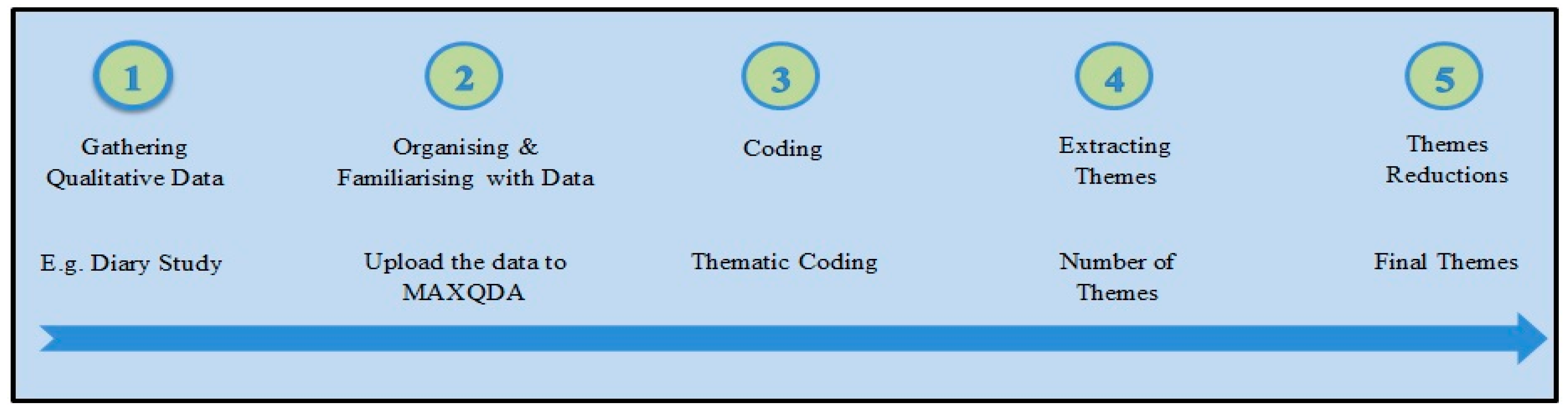

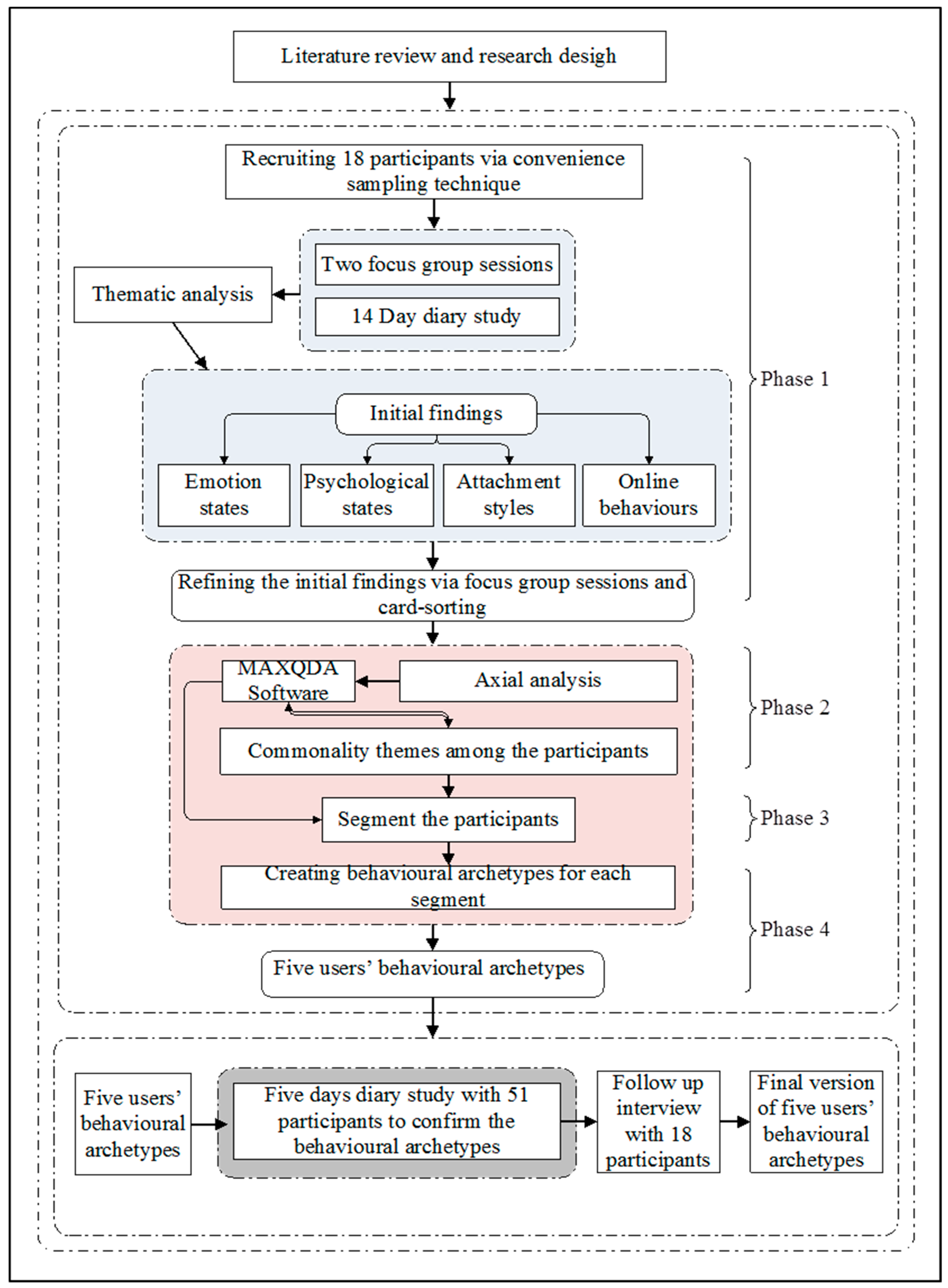

3. Behavioural Archetypes Creation and Validation: Our Research Method

3.1. First Phase: Qualitative Study

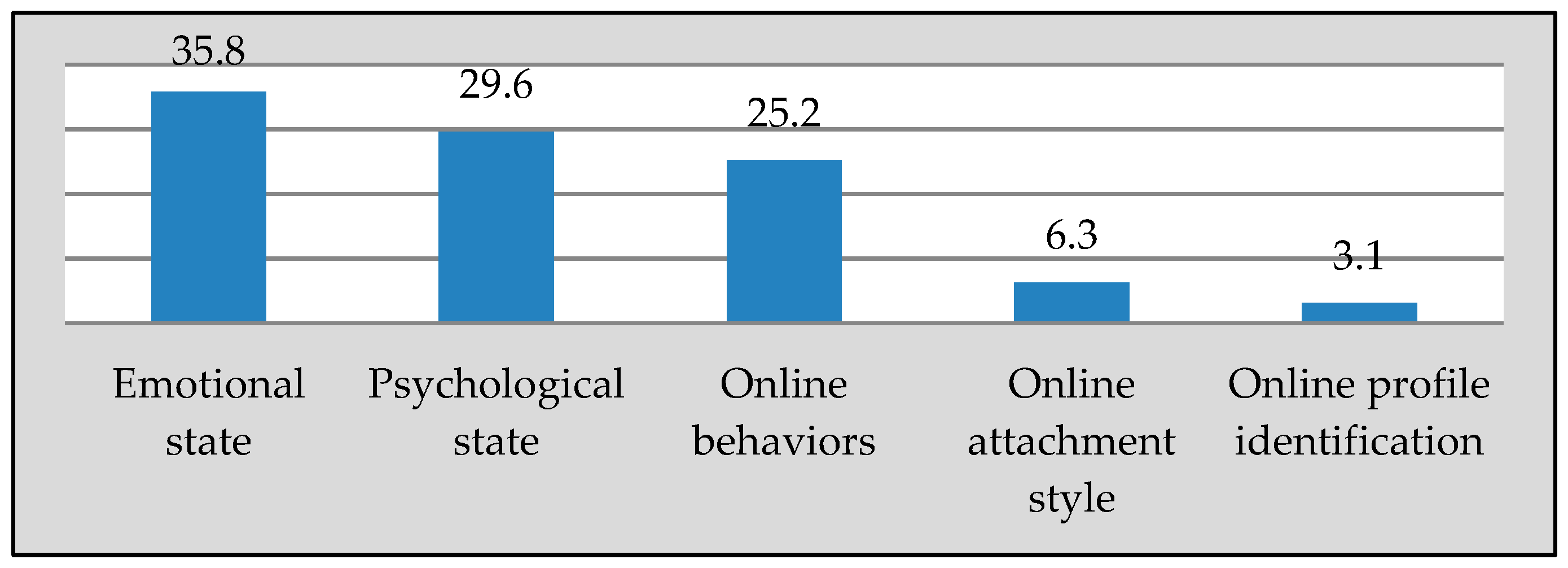

3.2. Second Phase: Segmentation of Participants Based on the Qualitative Data

- What attachment style has contributed to the participant’s problematic usage?

- What are the main features of the participant’s online behaviour that could be classed as problematic?

- What is the participant’s identification for online interaction?

- What online behaviours have contributed to the participant’s problematic usage?

3.3. Third Phase: Creating a Behavioural Archetype for Each Segment

3.4. Fourth Phase: Developing and Validating Behavioural Archetypes

4. Problematic Attachments to Social Media: Our Five Behavioural Archetypes

- Description: a brief overview of the behaviour archetype.

- Internal characteristics: attachment style, identity disclosure, social activeness, online behaviours, and personal attributes.

- Emotional states and examples: common user experiences and examples of associated emotions. Users’ experiences and associated emotions are split into positive and negative emotions. We utilised Parrott’s framework [77] to differentiate between primary, secondary, and tertiary emotions. The components of this section of the behavioural archetype were based on our previous research results in [73] on the relation between usage experiences and emotional states for people with problematic attachment to social media.

- Psychological states and examples: common user experiences and examples of associated psychological states. The components of this section of the behavioural archetype were based on our previous research results in [74] on the relation between usage experiences and psychological states for people with problematic attachment to social media.

4.1. Secure Behavioural Archetype

- Identity: Their online identities usually reflect their real offline identity through the use of their real name and image. People of this archetype possess self-confidence. Revealing their true personality online is an effective means of ensuring their popularity and forming friendships. This may directly affect their behaviour on social media, including their attachment: “I suppose my online identity while I am active online on Facebook and WhatsApp is a secure identity, which reflects my real character and personality, as well helping to build trust in social media.” The core characteristics of this archetype are the ability to trust in others and positive expectations of both self and others: “I feel happy and secure when people are there when I need them”.

- Common features of this archetype include a desire to search for information through social media, due to its accessibility, which can promote joy, particularly if the information is positive. By contrast, a lack of information leads to feelings of fear and loss.

- This archetype is also socially active, sharing information online and forming friendships within closed groups. This is due to being deterministic, which increases their social capital and social ties [78], prompting feelings of security, which influence their use of social media as an essential aspect of their daily life. However, this may also result in feelings of isolation when faced with any decrease in interaction within these groups or when subjected to discrimination or exclusion from these groups. Exclusion from online social groups may result in negative emotions, including nervousness, anger, or a lack of happiness: “the Internet connection in my residence is so weak that I could not interact online with my friends, which made me feel isolated from the world”.

- There are a number of emotions and psychological states that are prominent in the previous points (i.e., the positive interaction with social media profiles through comments or positive feedback) which revolve around a sense of liking and satisfaction. These can improve people’s self-perception, leading to higher levels of self-esteem [79], and are thus capable of triggering the evolution of an online presence. Hence, easy online communication with relatives and friends (including sharing of news) has a positive impact on the emotions of Secure users: “I feel really happy because I had a great chat with my family and friends and found lots of things online that made me joyous”.

4.2. Intimate Behavioural Archetype

- The Intimate user’s online identity is real, and his or her real name and a genuine self-image are used in profiles, i.e., self-disclosure [80]. In addition, Intimate users frequently update their profile image because they want to show their friends and social media contacts their appearance. This helps them to make new friends, and they like to diversify their friends from different cultures and geographical areas, and this makes them feel happy and joyous: “I took some pictures of myself and decided to use a new one for my profile to share with my family and friends.”

- The core of the Intimate archetype is kindness in online interactions. The Intimate user feels confident and trustworthy and pays attention to others, helping them to address their difficulties: “I am always a good listener and my friends and relatives like talking to me about their feelings and problems”. Furthermore, the Intimate user’s emotions are explicit throughout his or her online interactions.

- Very active in terms of appearance and participation with others on social media. This helps Intimate users gain a reputation and form friendships, which may facilitate the evolution of problematic attachment. Friendships are satisfying, but comparisons with social media peers may provoke jealousy or envy: “I was jealous when I saw my friend’s posts, and I compare them with my day; I wish I could be like him”. Intimate users also experience anxiety and a loss of interest if faced with disagreeable friends or uncomfortable online content. This results in feelings of dislike and neglect: “I did a favour to someone who knows me from Facebook. Later on, he started sending lots of messages, which I disliked”.

- Intimate users feel positive and satisfied as a result of their online interactions. This leads to a secure attachment to social media, particularly in the context of friendships. It enhances the evolution of their online presence and makes them feel safe. Curiosity is also important and their attachment to social media may result in fear of missing out. Intimate users are eager to know what is taking place around them in the online world, especially their close circle.

- Intimate users may feel a kind of depression if one of their online friends is no longer available or when they engage in downward social comparisons with others; this leaves a feeling of lack of social support. They may enjoy new friendships yet also feel regret or anger about the amount of time they spend on social media: “I feel regret; I have lost precious time on social media” or consider that they spend too much time posting and disclosing details of their personal life. Table 6 will present indepth details about Intimate archetype.

4.3. Escapist Behavioural Archetype

- The Escapist is often anonymous online, due to an unwillingness to form friendships that are more than temporary and because the practices of their real life are aimed at adjusting their mood and obtaining some entertainment. This gives the Escapist positive emotions, such as joy and pleasure, but they may feel regret if these positive emotions are delayed for a long period of time. The Escapist tends to be unconscious of their online interaction, leading one to ignore friends communications on social media or to procrastination and, hence, leading to negative emotions, such as sadness: “Sometimes I use social media unconsciously, by which I mean that I see some friends texting, but I am in the kind of mood where I’ll open and read their messages but not respond and then feel sad”.

- The Escapist may also have some kind of self-discrepancy [82]. The Escapist’s online personality may differ considerably from their real personality; they may pretend to be happier or younger online: “Online interaction sometimes forces me to respond to people I do not want to talk to”. Escapists may play a role and act in order to garner sympathy and boost their self-confidence.

- Escapists have an avoidant attachment to social media. They wish to be self-reliant and, therefore, do not aspire to form deep friendships with others through social media, choosing instead to entertain themselves in their own way [83].

- Some of their patterns of use may cause side effects resulting in negative emotions. For example, Escapists may categorise themselves according to factors such as interests, age, gender, or membership of an occupational group: “I am trying to contact journalists who with a similar background”. This approach may lead to loneliness and isolation, accompanied by other negative emotions, such as sadness, anger, and regret, with significant negative consequences for their self-conception. Table 7 will present indepth details about Escapist archetype.

4.4. Narcissist Behavioural Archetype

- Narcissists struggle to resist using social media and respond promptly to messages, taking part in conversations, comments, or the exchange of information. They tend to manipulate and update their profile content, including posting and changing their profile status: “I shared something via Facebook and I saw that everybody liked it; that made me happy”; “As soon as I woke up I used my social network and shared a lot of pictures and videos. I felt amazing today”. This interaction pattern may result in an evolution of their online presence and anxiety may arise from concerns about the expectations of others, perhaps leading to negative emotions such as nervousness, worry, and shame.

- Narcissists use their real identity for their online profile. This is a self-presentational choice and brings joy and satisfaction. Narcissists use a genuine self-image on their online profile, because they typically believe themselves to be attractive, both as appearance and lifestyle, and so they think that this will help them to be noticed and so achieve their social identity goals: “I have changed the profile picture I use on Facebook for family, relatives, and friends, because I took a new picture of myself”.

- Narcissists are influenced by their peers, leading to a form of competition in the use of social media, i.e., they are easily manipulated and feel they are at the centre of any interaction. Their self-categorisation is predictable, which results in them comparing themselves with others and may lead to negative emotions, such as envy and jealousy. Table 8 will present indepth details about Narcissist archetype.

4.5. Discrepancy Behavioural Archetype

- Discrepancy users’ profiles are frequently linked to their real identity because they see themselves as different from others and tend to classify themselves according to their feelings of self-worth and their self-perception: “I am trying to be myself. Also, I like to share posts with my friends who have the same interests”. Their attachment to social media takes an avoidant style, due to their focus on creating and maintaining self-esteem, in a number of different ways and on different levels, using the features and functions of social media. They may experience regret or anger as a result of the amount of time they spend online, on such activities.

- They also feel disturbed and lose concentration when their thinking is dominated by online activities to the extent that they are unable to focus on anything else. This leads them to lose interest in using social media, giving rise to negative emotions, such as nervousness and anger: “When I was checking my message I lost my concentration, and I missed an important task, which makes me feel anger”.

- Their interactions are unlike those of other behavioural archetypes, in that they are discriminating and selective when it comes to content posted to their accounts (including posts or comments) because they suffer from social anxiety: “I care about my appearance. I want people to see me as good looking and happy, even if that is far from the reality”. In addition, they expect a lot from their online friends, which makes them feel anxious and lonely and may lead to other negative emotions, such as fear and nervousness: “I was expecting a message, and I felt lonely while I was waiting”. Table 9 will present indepth details about Discrepancy archetype.

5. Evaluation of the Behavioural Archetypes: Analyzing Participants Feedback’s

- Representative nature: Participants believed that these behavioural archetypes were able to capture the main problematic online attachment style, making it easy for them to liaise to one of these archetypes. In addition, they began to understand and predict patterns of interaction with people around them. This can be attributed to the nature of the building components of the developed archetypes, which makes them closer to reflecting reality. Examples of the comments received included “I definitely can find one more characteristic that I have it myself in behavioural archetype number four” and ““I found that easy to put myself in one of these behavioural archetypes, which is good to see my usage in front of me”, and “The five behavioural archetypes are well-structured and put together. I found it relatively easy to link to one of them and populate my daily diary”. The representation nature of our five archetypes is also supported by the fact that each of the recruited participants, the 51 participants of the second diary study, found themselves in one of the archetypes.

- Raising awareness towards the interaction style: Participants agreed that the diary study and their completion of the sheets on a daily basis made them more conscious about their online behaviours and their problematic online attachment. They started to think of managing it during the diary study period. Examples of the comments received on this aspect include “To be honest, these behavioural archetypes prompted me to think about how to use social networking sites” and “I would like to thank you because I started thinking about social media effects”, and “I realised my patterns are from behavioural archetype one, which exactly reflects my interaction.”

- Terminology awareness: Some participants thought that there was an overlap between emotions and psychological states in each of the five behavioural archetypes, some of which are difficult to distinguish and needed further clarification. For example, participants mentioned they tended to see negative emotions and some psychological states as a similar thing, occasionally. They also found the subtle differences between emotions hard to recognise, and some could not differentiate between certain emotions of a similar nature, such as anxiety and regret and sadness. This suggests that an induction around emotions and the psychological states would be needed when behavioural archetypes are used for user modelling and behaviour awareness.

- Engaging presentation: At the start of the diary study (phase four), participants were presented with a summary description of each of the personas written in a simple and concise format. They were asked to liaise themselves with one or more of the behavioural archetypes. Based on their choice, participants were then given a diary book including entries tailored to the detailed description of that archetype. While participants found the detailed form helpful to self-diagnose their actual experience, they also expressed that the questions were of a “dry nature” and “heavy at times”. Hence, a more user-friendly and lively format of the behavioural archetypes would need to be presented to people if the intention is to use the behavioural archetypes for design or diagnosis purposes, to avoid causing a tiring and less engaging experience.

- Behavioural archetypes’ live presentation and representation: A set of live behavioural archetypes were created in response to the previous point around the need for an engaging presentation. The behavioural archetypes were presented in the follow-up interviews. However, some participants expressed concerns about the names of the behavioural archetypes, especially the Narcissist and the Paranoid. We stress here that these names were hidden from the actual studies and only used at that phase for consultation. Still, we replaced Paranoid with Discrepancy. Participants also felt that demographic data added to each behavioural archetype could be seen as stereotyping. The archetype names used in this paper are meant for the practitioners and researchers, and we would need more user-friendly terminology and presentation if used for other purposes, such as validating a design or eliciting user requirements. In addition, it appeared that assigning gender and age to a behavioural archetype may deter some from choosing it or liaising themselves naturally to it.

- Objectivity and influence: Participants noted that they could be biased in filling the diary and recognising their behavioural archetypes altogether. For example, one participant mentioned that emotion could be volatile depending on the different interactions they have on their different social media accounts, and, at times, they may feel “different emotions simultaneously”, according to the various messages and content received. They also noted that “being in a negative mood due to a real-world event can expand to the low mood in using social media and vice versa”. Hence, the emotions and psychological states associated with the use of social media should not be attributed to that use entirely. A more objective measure of that relation, other than the self-report, is, therefore, needed.

6. Quantitative Validation on Behavioural Archetypes

6.1. Sample Overview

6.2. Quantitative Validation of the Behavioural Archetype

6.3. Descriptive Statistics for Each Behaviour Archetype

6.4. Internal Characteristics Validity Measure for Behavioural Archetype

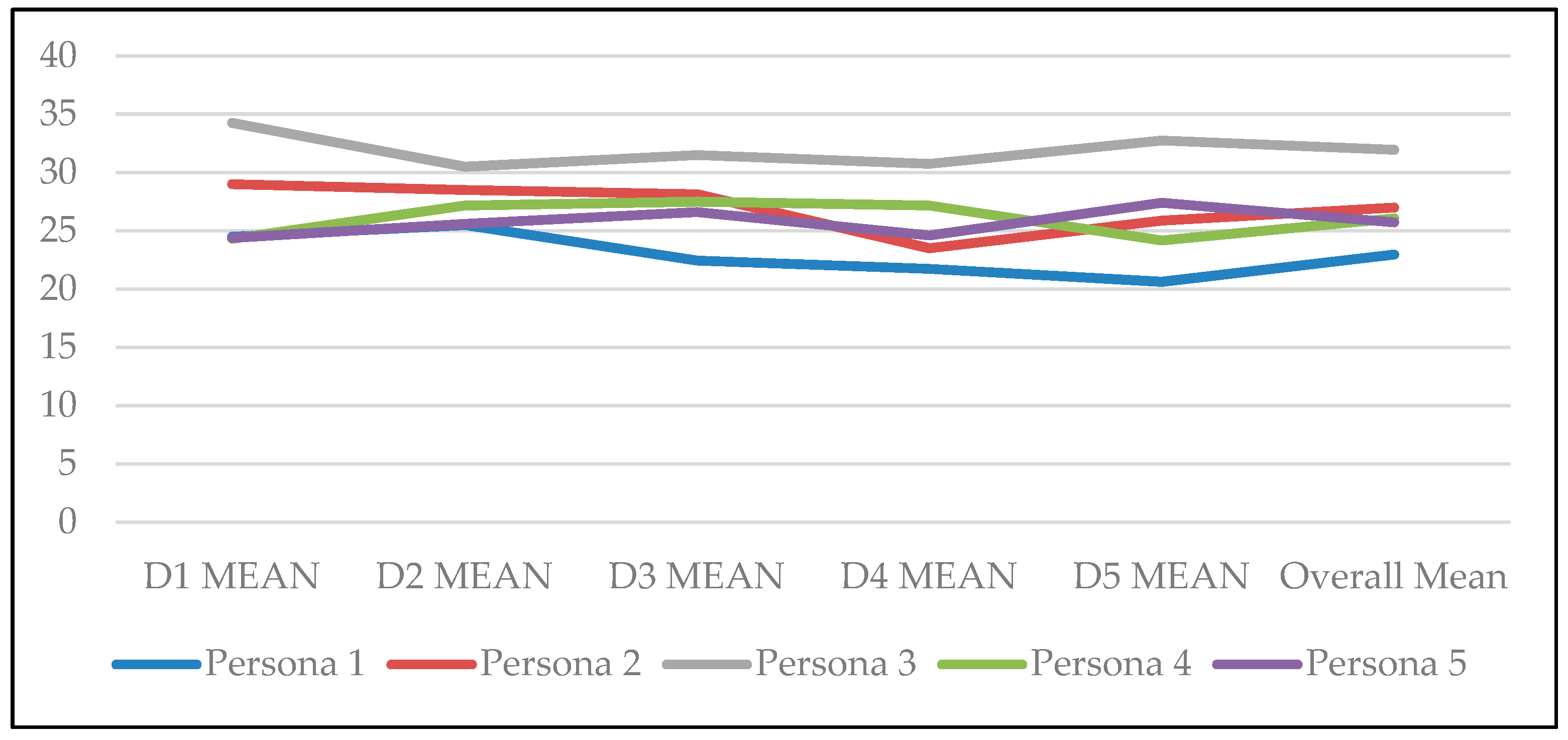

6.5. Stability of Behavioural Archetype

7. Discussion

- They facilitate the design process that engineers connect to a human face and name rather than the abstract user data.

- They provide a common, fast, and effective form of communication between software engineers and designers.

- They help engineers maintain a focus on a limited subset of users (archetype) at a time that can result in more robust design decisions.

- They are useful for system validation purposes, where proposed designs, features, and solutions can be examined against the needs defined in the archetype.

Limitations

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Demographic Variable | No. of Participants | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 9 |

| Female | 9 | |

| Age in years | 18–24 | 9 |

| 25–34 | 8 | |

| 35–44 | 1 | |

| 45 or older | - | |

Appendix A.1. Exploratory Study: Analysis

| Data Extract | Code |

|---|---|

| At the moment I am really excited and happy because my number of followers increased and my timeline is active | Feeling Reputation |

Appendix A.2. Validation Study

References

- Turkle, S. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other; Hachette: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, A.L.; Hancock, J.T. Mirror, mirror on my Facebook wall: Effects of exposure to Facebook on self-esteem. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2011, 14, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinfield, C.; Ellison, N.B.; Lampe, C. Social capital, self-esteem, and use of online social network sites: A longitudinal analysis. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2008, 29, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, H.C.; Scott, H. # Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. J. Adolesc. 2016, 51, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- El Asam, A.; Samara, M.; Terry, P. Problematic internet use and mental health among British children and adolescents. Addict. Behav. 2019, 90, 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matos, A.P.; Costa, J.; Pinheiro, M.; Salvador, M.; Vale-Dias, M.; Zenha-Rela, M. Anxiety and dependence to Media and Technology Use: Media technology use and attitudes, and personality variables in Portuguese adolescents. J. Glob. Acad. Inst. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2016, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K.S. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Review of research on problematic Internet use and well-being: With recommendations for the US Air Force. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.881.2613&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 11 June 2019).

- J. Kuss, D.; D. Griffiths, M.; Karila, L.; Billieux, J. Internet addiction: A systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 4026–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, R.; Vangeel, J.; Klein, A.; Minotte, P.; Rosas, O.; Meerkerk, G.-J. Compulsive use of social networking sites in Belgium: Prevalence, profile, and the role of attitude toward work and school. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyanto, L.; Griffiths, M. ‘Internet addiction’: A critical review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2006, 4, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.; Condron, L.; Belland, J.C. A review of the research on Internet addiction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2005, 17, 363–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O. Generalised Versus Specific Internet Use-Related Addiction Problems: A Mixed Methods Study on Internet, Gaming, and Social Networking Behaviours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrobai, A.; Phalp, K.; Ali, R. Digital Addiction: A Requirements Engineering Perspective. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality (REFSQ), Essen, Germany, 7–10 April 2014; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 112–118. [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga, R.S.; Rains, S.A. A review and meta-analysis examining conceptual and operational definitions of problematic Internet use. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 165–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D.; Griffiths, M. Social networking sites and addiction: Ten lessons learned. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spada, M.M. An overview of problematic Internet use. Addict. Behav. 2014, 39, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowlby, J.; May, D.S.; Solomon, M. Attachment Theory; Lifespan Learning Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arienzo, M.C.; Boursier, V.; Griffiths, M.D. Addiction to Social Media and Attachment Styles: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M.D.; Kuss, D.J.; Demetrovics, Z. Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In Behavioral Addictions; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 119–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kuss, D.J.; Griffiths, M.D. Online social networking and addiction—A review of the psychological literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2011, 8, 3528–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paris, C.M.; Berger, E.A.; Rubin, S.; Casson, M. Disconnected and unplugged: Experiences of technology induced anxieties and tensions while traveling. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 803–816. [Google Scholar]

- Ofcom. The Communications Market Report 2017; Ofcom: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/multi-sector-research/cmr/cmr-2017 (accessed on 9 May 2019).

- Ali, R.; Jiang, N.; Phalp, K.; Muir, S.; McAlaney, J. The emerging requirement for digital addiction labels. In Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Requirements Engineering: Foundation for Software Quality, Essen, Germany, 23–26 March 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 198–213. [Google Scholar]

- Alutaybi, A.; McAlaney, J.; Stefanidis, A.; Phalp, K.; Ali, R. Designing Social Networks to Combat Fear of Missing Out. In Proceedings of the British HCI, Belfast, UK, 4–6 July 2018; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, P.-L.P.; Gao, Q.; Ding, Y. Relationship between the level of intimacy and lurking in online social network services. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2008, 24, 2757–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barke, A.; Nyenhuis, N.; Kröner-Herwig, B. The German version of the internet addiction test: A validation study. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2012, 15, 534–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monacis, L.; de Palo, V.; Griffiths, M.D.; Sinatra, M. Exploring individual differences in online addictions: The role of identity and attachment. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2017, 15, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-H. Need for relatedness: A self-determination approach to examining attachment styles, Facebook use, and psychological well-being. Asian J. Commun. 2016, 26, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldmeadow, J.A.; Quinn, S.; Kowert, R. Attachment style, social skills, and Facebook use amongst adults. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1142–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.; Shamim, A. Malaysian Facebookers: Motives and addictive behaviours unraveled. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, M.; Shrout, P.E.; Laurenceau, J.-P.; Bolger, N. Using diary methods in psychological research. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol. 1. Foundations, Planning, Measures, and Psychometrics; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A. The Inmates Are Running the Asylum:[Why High-Tech Products Drive Us Crazy and How to Restore the Sanity]; Sams: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1999; Volume 261. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, I.R.; Cameron Jones, M.; Twidale, M.B. Resolving incommensurable debates: A preliminary identification of persona kinds, attributes, and characteristics. Artifact 2008, 2, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelson, N.; Lee, W.O. Incorporating User Archetypes into Scenario-Based Design. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Usability Professionals’ Association Conference (UPA), Asheville, NC, USA, 14–18 August 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-N.; Lim, Y.-K.; Stolterman, E. Personas: From theory to practices. In Proceedings of the 5th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Building Bridges, Lund, Sweden, 20–22 October 2008; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 439–442. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero, D.G.; Winschiers-Theophilus, H.; Abdelnour-Nocera, J. Reconceptualising personas across cultures: Archetypes, stereotypes & collective personas in pastoral Namibia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Culture, Technology, and Communication, London, UK, 15–17 June 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 96–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L. Engaging Personas and Narrative Scenarios. Ph.D. Thesis, Copenhagen Business School, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, A.; Reimann, R.; Cronin, D. About Face 3: The Essentials of Interaction Design; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Long, F. Real or imaginary: The effectiveness of using personas in product design. In Proceedings of the Irish Ergonomics Society Annual Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 14 May 2009; Irish Ergonomics Society: Dublin, Ireland, 2009; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Littrell, J. How addiction happens, how change happens, and what social workers need to know to be effective facilitators of change. J. Evid.-Based Soc. Work 2011, 8, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandell, J.J. Internet addiction on campus: The vulnerability of college students. CyberPsychol. Behav. 1998, 1, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann Stoddard Dare, P.; Derigne, L. Denial in alcohol and other drug use disorders: A critique of theory. Addict. Res. Theory 2010, 18, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, M.W.; Oswald, D.L.; Bull, F.C.; Clark, E.M. Are tailored health education materials always more effective than non-tailored materials? Health Educ. Res. 2000, 15, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.M.; Updegraff, J.A. Health message framing effects on attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A meta-analytic review. Ann. Behav. Med. 2011, 43, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, P.A.; Lehmann, D.R. Designing effective health communications: A meta-analysis. J. Public Policy Mark. 2008, 27, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustria, M.L.A.; Noar, S.M.; Cortese, J.; Van Stee, S.K.; Glueckauf, R.L.; Lee, J. A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 1039–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, G. Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personal. Indivd. Differ. 2013, 54, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Ahn, J.; Kim, Y.J. Personality traits and self-presentation at Facebook. Personal. Indivd. Differ. 2014, 69, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffardi, L.E.; Campbell, W.K. Narcissism and social networking Web sites. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 34, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh, S. Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2010, 13, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, J.L.; Campbell, W.K. Narcissism and social media use: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2018, 7, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircaburun, K.; Alhabash, S.; Tosuntaş, Ş.B.; Griffiths, M.D. Uses and gratifications of problematic social media use among university students: A simultaneous examination of the Big Five of personality traits, social media platforms, and social media use motives. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2018, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaite, E.O.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Colditz, J.B.; Primack, B.A. Social media use, personality characteristics, and social isolation among young adults in the United States. Personal. Indivd. Differ. 2018, 124, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L.R. An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McCrae, R.R. Four ways five factors are basic. Personal. Indivd. Differ. 1992, 13, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.; Orr, E.S.; Sisic, M.; Arseneault, J.M.; Simmering, M.G.; Orr, R.R. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2009, 25, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amichai-Hamburger, Y.; Vinitzky, G. Social network use and personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, S.; Yaar, Z. The User Is always Right: A Practical Guide to Creating and Using Personas for the Web; New Riders: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, N.; Fonagy, P. Attachment and personality disorders: A short review. Focus 2013, 11, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.A. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.L.S.; Valença, A.M.; Silva, A.; Baczynski, T.; Carvalho, M.; Nardi, A.E. Nomophobia: Dependency on virtual environments or social phobia? Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, T.; Chester, A.; Reece, J.; Xenos, S. The uses and abuses of Facebook: A review of Facebook addiction. J. Behav. Addict. 2014, 3, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stryker, S. Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. J. Marriage Fam. 1968, 30, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Terry, D.J.; White, K.M. A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1995, 58, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Identity theory and social identity theory. Soc. Psychol. Q. 2000, 63, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Hutton, D.G. Self-presentation theory: Self-construction and audience pleasing. In Theories of Group Behavior; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1987; pp. 71–87. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Sparks, E.A.; Stillman, T.F.; Vohs, K.D. Free will in consumer behavior: Self-control, ego depletion, and choice. J. Consum. Psychol. 2008, 18, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent developments in role theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S. The self-concept revisited: Or a theory of a theory. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caplan, S.E. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altuwairiqi, M.; Kostoulas, T.; Powell, G.; Ali, R. Problematic attachment to social media: Lived experience and emotions. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (WorldCIST), Galicia, Spain, 16–19 April 2019; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Altuwairiqi, M.; Arden-Close, E.; Jiang, N.; Powell, G.; Ali, R. Problematic Attachment to Social Media: The Psychological States vs Usage Styles. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), Brussel, Belgium, 29–31 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, K. Perfecting your personas. Cooper Interact. Des. Newslett. 2001, 19, 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L.; Storgaard Hansen, K. Personas is applicable: A study on the use of personas in Denmark. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Toronto, ON, Canada, 26 April–1 May 2014; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1665–1674. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott, W.G. Emotions in Social Psychology: Essential Readings; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri, M.A.; Wright, S.L.; Hudiburgh, L.M. The relationships among attachment style, personality traits, interpersonal competency, and Facebook use. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 33, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest, A.L.; Wood, J.V. When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 23, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S.; Hendrick, S.S. Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 23, 857–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. Does Internet and computer” addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychol. Behav. 2000, 3, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E.T. Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychol. Rev. 1987, 94, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; Nailling, E.; Bizer, G.Y.; Collins, C.K. Attachment theory as a framework for explaining engagement with Facebook. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 77, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, C.J. Narcissism on Facebook: Self-promotional and anti-social behavior. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 482–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldiera, V.R.B.G.; Rombach, H.D. The goal question metric approach. In Encyclopedia of Software Engineering; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 528–532. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, L. From user to character: An investigation into user-descriptions in scenarios. In Proceedings of the 4th Conference on Designing Interactive Systems: Processes, Practices, Methods, and Techniques, London, UK, 25–28 June 2002; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Miaskiewicz, T.; Kozar, K.A. Personas and user-centered design: How can personas benefit product design processes? Des. Stud. 2011, 32, 417–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeRouge, C.; Ma, J.; Sneha, S.; Tolle, K. User profiles and personas in the design and development of consumer health technologies. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2013, 82, e251–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosbergen, S.; Mulder-Wiggers, J.; Lacroix, J.; Kemps, H.; Kraaijenhagen, R.A.; Jaspers, M.W.; Peek, N. Using personas to tailor educational messages to the preferences of coronary heart disease patients. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 53, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, A.M.; Reeder, B.; Ramey, J. Scenarios, personas and user stories: User-centered evidence-based design representations of communicable disease investigations. J. Biomed. Inform. 2013, 46, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrero, D.G.; Kapuire, G.K.; Winschiers-Theophilus, H.; Stanley, C.; Abdelnour-Nocera, J. A UX and Usability expression of Pastoral OvaHimba: Personas in the Making and Doing. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference in HCI and UX Indonesia 2016, Jakarta, Indonesia, 13–15 April 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Whitemore, J. Coaching for Performance: Growing People, Performance and Purpose; Nicholas Brearley: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Pub: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahri, A.; Hosseini, M.; Almaliki, M.; Phalp, K.; Taylor, J.; Ali, R. Engineering software-based motivation: A persona-based approach. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Tenth International Conference on Research Challenges in Information Science (RCIS), Grenoble, France, 1–3 June 2016; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Shakya, H.B.; Christakis, N.A. Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 185, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSmet, A.; Thompson, D.; Baranowski, T.; Palmeira, A.; Verloigne, M.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I. Is participatory design associated with the effectiveness of serious digital games for healthy lifestyle promotion? A meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, D.; Namioka, A. Participatory Design: Principles and Practices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Alrobai, A.; McAlaney, J.; Phalp, K.; Ali, R. Exploring the risk factors of interactive e-health interventions for digital addiction. In Substance Abuse and Addiction: Breakthroughs in Research and Practice; IGI Global: London, UK, 2016; pp. 375–390. [Google Scholar]

- Minian, N.; Noormohamed, A.; Zawertailo, L.; Baliunas, D.; Giesbrecht, N.; Le Foll, B.; Rehm, J.; Samokhvalov, A.; Selby, P.L. A method for co-creation of an evidence-based patient workbook to address alcohol use when quitting smoking in primary care: A case study. Res. Involv. Engagem. 2018, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollnick, S.; Miller, W.R. What is motivational interviewing? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1995, 23, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. Am. Psychol. 2002, 57, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L.; Scott, S.; Cavers, D.; Campbell, C.; Walter, F. Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, B.L.; Lune, H.; Lune, H. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2004; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

| Online Behaviours | Online Attachment Style | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) | Avoidant | |

| Self-enhancement | Segment 3 | ||

| Irresistible urge and self-disclosure | Segment 4 | ||

| Categories themselves | Segment 5 | ||

| Tracking information | Segment 1 | ||

| Kindness and self-presentation | Segment 2 | ||

| Online Behaviours | Behavioural Archetype for Each Segment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Self-enhancement | Escapism archetype | ||

| Irresistible urge and self-disclosure | Narcissism archetype | ||

| Categories themselves | Discrepancy archetype | ||

| Tracking information | Secure archetype | ||

| Kindness and self-presentation | Intimacy archetype | ||

| No. # | Archetype Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Secure archetype | This archetype likes to feel assured. Social media helps them to maintain this feeling by building successful relationships that increase their connectedness and presence. Despite this, they can occasionally lose their sense of security, i.e., when unable to access social media, interact with peers, or express themselves and receive the responses they feel they need to maintain their desired level of social presence and connectedness. |

| 2 | Intimate archetype | These individuals become closely attached to their social media and their online friends. This commitment to their friends manifests as a keen interest in their activities and (when appropriate) empathetic responses. They know what they like and refuse to engage with the material of which they disapprove. Their natural curiosity and vulnerability to the fear of missing out can lead them to become anxious if they are unable to maintain an online presence. |

| 3 | Escapist archetype | These users employ social media to avoid the reality of their own lives. They may engage in anonymously or create fictitious online personalities. They have little desire to form real relationships offline and use social media for entertainment. Their behaviour could easily exacerbate their true loneliness. |

| 4 | Narcissist archetype | These individuals pay excessive attention to the thoughts and opinions of others about them on social media and they often seek approval from others. They lack the confidence to use their real identity on social media but have an urge to respond as soon as possible to updates. Social media are used as a way of competing with others, but there is potential for discontent or jealousy if they feel their contacts are experiencing more enjoyment or achieving more than they are. |

| 5 | Discrepancy archetype | This archetype spends a considerable amount of time attempting to boost his or her self-esteem on social media, but this frequently leads to feelings of regret, including the feeling of having wasted time that could have been spent doing other things. Even when engaged in other offline activities, these users are likely to think about social media, which can have an adverse influence on their daily lives. In addition, they may feel excluded and alone if social media contacts do not live up to their high expectations. |

| Internal Characteristics | SM Boosts the Feeling of Being Secure | SM Boosts Perceived Security and Fear of Missing out | Avoidant Online Attachment Style | Committed to Online Group | Socially Active | Tracking Information | Self-Presentation | Kindness Role | Trust and Positive Expectation | Self-Enhancement | Procrastination | Self-Discrepancy | Vulnerable to Peer Pressure | Irresistible Urge | Disturbance and Loss of Concentration | Categories Themselves | Detached from Reality | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online Behavioural Archetypes | ||||||||||||||||||

| Secure archetype | ◯ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ||||||||||||||

| Intimate archetype | ✕ | ◯ | ✕ | ✕ | ||||||||||||||

| Escapist archetype | ◯ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ||||||||||||||

| Narcissist archetype | ◯ | ◯ | ✕ | ✕ | ||||||||||||||

| Discrepancy archetype | ◯ | ✕ | ✕ | ✕ | ||||||||||||||

| Secure Behavioural Archetype | ||

| Internal Characteristics | Description | |

| Identity | Feels confident using information that identifies him/her in interactions online, e.g., real (or close to real) name, real (or close to real) picture, along with location, place of work, and email address | |

| Social media boosts the feeling of being secure | Interacting online contributes to a feeling of safety and confidence. Value peer support and continual presence | |

| Tracking information | Considers it important and worthwhile to search for events, feed requests, and news on social media. Keeps up to date with information and has a reasonable response time | |

| Socially active | Is active on social media (i.e., posting and commenting) and enjoys being involved in groups and establishing new connections | |

| Committed to their online group | Likes to maintain relationships with others and tolerates situations in which this may require acceptance of different attitudes and styles of interactions | |

| Examples of Usage and Associated Emotions (Positive and Negative) | Emotion Example | |

| Positive usage experience | Social media used as a medium for reciprocal messaging, posting and commenting, i.e., interactive social communication | Satisfaction, liking, joy |

| Social media as an accessible facilitator of activities related to pleasure and entertainment | Joy | |

| Social media help communicate with relatives and friends, as well as sharing information and contributes to a sustainable sense of connectedness and presence | Happiness, joy, astonishment | |

| Negative usage experiences | Using social media for longer than required | Regret, anger |

| Limited or no access to social media due to connectivity problems or restrictions imposed by the social context | Nervous, anger, fury, unhappiness | |

| Not receiving sufficient or timely responses from peers when looking for support or socialisation | Anger, sadness | |

| Fear of missing out on certain events, news, opportunities, and timely interactions | Worry, fear, jitteriness | |

| Psychological States | Usage Experiences | |

| Loss of interest | When information content, interactions, and contacts do not change and when they become repetitive | |

| Anxiety | When spending too much time on social media or when dissatisfied with the content, interaction and unable to do much to change it | |

| Boredom | When there is nothing new on one’s social media which make them scrolling through content without conscious | |

| Loneliness | Being unable to connect and interact or receive responses as desired | |

| Craving | When there is a pressing need to shape and maintain one’s online identity and self-concept which in turn increases their reputation | |

| Intimate Behavioural Archetype | ||

| Internal Characteristics | Description | |

| Identity | Feels confident and needs to use their real name and image for online profiles; updates his or her profile picture regularly | |

| Kindness role | Has inner confidence and is eager to help others by listening to their problems and offering help | |

| social media boosts the feeling of being secure and FoMO | Comfortable when engaging online, but natural curiosity means that any interruption to online activities can result in fear of missing out | |

| Self-presentation | Confident about personal appearance and regularly changes his or her profile picture as a reminder of his/her presence and current status. This may also result in a tendency to compare their life with the perceived lives of others | |

| Trust and positive expectation | Believes that his or her online friends can be relied on and is, therefore, keen to interact with them | |

| Examples of Usage and Associated Emotions (Positive and Negative) | Emotion Example | |

| Positive usage experiences | Social media are a tool for communicating with friends and family | Happiness, joy, astonishment |

| Social media are useful for reciprocal messaging, posting, and commenting, i.e., interactive social communication | Satisfaction, liking, joy | |

| Social media as a source of fun and entertainment | Pleasure, joy | |

| The Intimate user is well-liked and social media are a useful way of making many friends from various locations and backgrounds | Happiness, enjoyment, satisfaction | |

| Negative usage experiences | Using social media for longer than required | Regret, anger |

| Unwelcome communications received online, including disagreeable messages from friends, inappropriate subject matter, or comments with which one disagrees | Dislike, neglect | |

| Use of social media to compare one’s own life with those of one’s contacts | Jealousy, unhappiness | |

| Limited or no access to social media due to connectivity problems or restrictions imposed by a specific social context | Nervousness, anger, fury, unhappiness | |

| A continual need to know about contacts’ activities, resulting in fear of missing out | Worry, fear, jitteriness | |

| Psychological States | Usage Experiences | |

| Loss of interest | This occurs when there is little change of content, interaction, and contacts, resulting in the experience becoming repetitive | |

| Boredom | Arises when they lose popularity due to an inactive profile and the same content being posted | |

| Anxiety | This could result from spending too much time on social media, being unable to access social media. The belief that contacts expect a quick response to posts or online activity may also provoke anxiety | |

| Loneliness | Arises if, over time, the Intimate user comes to rely on social media in daily life and an inability to communicate leaves him or her feeling excluded | |

| Craving | This can arise in the face of routine. They are using social media on a daily basis which then turns into a daily habit | |

| Depression | This can occur when they engage in downward social comparison with others in order to meet self-evaluation needs | |

| Escapist Behavioural Archetype | ||

| Internal Characteristics | Description | |

| Identity | Escapists prefer to remain anonymous during online interactions | |

| Procrastination | They may postpone responses to their online friends and, unconsciously, leave their messages and interactions unanswered | |

| Self-enhancement motive | Social media offer an escape from real life, allowing the Escapist to create an imaginary persona that boosts his or her self-image and allows him or her to be viewed positively | |

| Self-discrepancy | Escapists’ unhappiness with their real-life situation causes them to make false claims about themselves when online, for example giving a false age or pretending to be happier than they really are | |

| Avoidant online attachment style | Escapists are unwilling to form close friendships online, which may reflect an underlying lack of trust in those with whom they engage | |

| Examples of Usage and Associated Emotions (Positive and Negative) | Emotion Example | |

| Positive usage experiences | Social media are helpful for communicating with relatives, friends, and sharing information | Happiness, joy, astonishment |

| Social media are used for activities resulting in pleasure and entertainment | Joy | |

| Negative usage experiences | Fear of missing out on certain events, news, opportunities, and timely interactions | Worry, fear, jitteriness |

| Unconsciously spending longer online than one intended; avoiding communicating with others | Regret, anger, sadness | |

| Limited or no access to social media due to connectivity problems or restrictions imposed by the social context | Nervous, anger, fury, unhappiness | |

| Content or interactions do not suit one’s mood | Anger | |

| Psychological States | Usage Experiences | |

| Anxiety | Occurs due to excessive usage of social media or due to displeasing content | |

| Boredom | Arises when the individual may engage in passive interaction such as viewing and scrolling in an unconscious mood | |

| Loss of interest | This arises when the same content is repeatedly posted on social media | |

| Loneliness | Arises if social media are crucial to social interaction and one is unable to engage and feels excluded | |

| Narcissist Behavioural Archetype | ||

| Internal Characteristics | Description | |

| Identity | Narcissists are sufficiently confident in their online interactions to use one or more items of information that identify them, e.g., real name, picture, location data, workplace, and email | |

| Self-presentation | Narcissists have a high opinion of themselves and use social media to show off their good qualities, including their physical appearance, personality and achievements, e.g., they frequently update their profile content in order to attract the attention of others. However, this leaves them vulnerable to comparisons with others that they may find it difficult to avoid | |

| Peer pressure | They are keen to impress their contacts and so may experience competitive pressures. They desire to be the centre of attention, and remaining thus requires considerable effort. | |

| Irresistible urge | They have an urge to respond to new posts and conversations and exchange information and content as soon as possible | |

| Secure and fear of missing out online attachment | Engaging with others via social media makes them feel secure and confident. If they cannot access social media, they may become uneasy and experience fear of missing out | |

| Examples of Usage and Associated Emotions (Positive and Negative) | Emotion Example | |

| Positive usage experiences | Social media are helpful for communicating with relatives and friends, sharing information and experiencing a sense of ongoing connection | Happiness, joy, astonishment |

| Social media are used for reciprocal messaging, posting and commenting, i.e., interactive social communication | Satisfaction, liking, joy | |

| Narcissists are well-liked and social media help them to make many friends from many different countries and cultures | Enjoyment, satisfaction | |

| Negative usage experiences | Social media-motivated comparisons between one’s own life and the lives of contacts, often in terms of their activities | Jealousy, unhappiness |

| Curiosity about their contacts’ activities can lead to fear of missing out if one is unable to access social media | Worry, fear, jitteriness | |

| Limited or no access to social media due to connectivity problems or restrictions imposed by the social context | Nervous, anger, fury, unhappiness | |

| Undesirable social media content and comments are posted by contacts they consider disagreeable | Dislike, neglect | |

| Psychological States | Usage Experiences | |

| Boredom | Arises when there is no new social media content or content is repetitive | |

| Loss of interest | Arises when social media contacts have failed to add any new content, or when one lacks time to access social media | |

| Loneliness | Social media are a key part of one’s social life, and one’s group memberships reflect one’s personal preferences | |

| Anxiety | Evoked by difficulty in accessing one’s profile or being unhappy with social media content. Anxiety may also result from a feeling of commitment to be a highly responsive and unconscious quick response | |

| Craving | In the form of a pressing need to shape and maintain one’s online identity, self-concept, and reputation | |

| Discrepancy Behavioural Archetype | ||

| Internal Characteristics | Description | |

| Identity | Discrepancy users use one or more items of information that identify them, e.g., real name, picture, location data, work place, and email, in online interactions | |

| Avoidant online attachment style | Discrepancy users are unwilling to form close bonds with people they engage with on social media and find it difficult to trust those they meet online | |

| Categorise themselves | Discrepancy users believe that they are special and contrast their own situation with their contacts’ situations by comparing profiles and activities | |

| Disturbance and lost concentration | The Discrepancy user finds that handling numerous interactions online simultaneously leads to a loss of concentration and so prefers to focus one interaction at a time | |

| Different from reality | The Discrepancy user behaves very differently online and in the real world | |

| Examples of Usage and Associated Emotions (Positive and Negative) | Emotion Example | |

| Positive usage experiences | Social media are an accessible facilitator of pleasure and entertainment activities | Joy |

| Social media are helpful for communicating with relatives and friends, including sharing information, resulting in a sustained feeling of connectedness and presence | Happiness, joy | |

| Negative usage experiences | Frequent online engagement, accompanied by a lack of self-awareness and concentration | Regret, anger |

| The fear of missing out on certain events, news, opportunities or interactions | Worry, fear, nervousness | |

| Failing to receive sufficient or timely responses from peers | Sadness | |

| Psychological States | Usage Experiences | |

| Boredom | Arises when their interaction is passive and unconscious | |

| Anxiety | Provoked by spending longer than intended on social media or being unable to check one’s profile | |

| Loss of interest | Caused by the disapproval of others’ content and interactions, or because the content remains unchanged or becomes repetitive | |

| Loneliness | They categorise themselves, which can result in feelings of isolation, particularly if contacts have not been active online | |

| Goal 1 Are the diary study data valid at the unit level? (for each participant) | |

| Questions Has each participant responded fully to all survey questions over the five days period? Are questions responded to in an honest manner? Has a participant exhibited variation in their responses? Is that variation reasonable? Are there any patterns within the data that should not be expected? Can any visible patterns be rationalised? Alternatively, should the participant be considered an outlier and their data removed? | Metrics Response Rate was calculated for each participant to identify potential outliers. Question Responses were analysed by summation for each participant, for each question for each participant and each survey for each participant (Section 6.1). |

| Goal 2 To understand the distribution of behavioural archetypes within a population | |

| Questions Are all behavioural archetypes equally likely to be chosen? Are behavioural archetypes related to gender? | Metrics Chi-Square Test of Behavioural Archetype according to frequency and gender (Section 6.2). |

| Goal 3 To understand whether the behavioural archetypes are related to emotional experience and psychological states | |

| Questions What are the differences (if any) in how respective behavioural archetypes relate to positive and negative emotions as well as psychological states? | Metrics Descriptive Statistics for each Behavioural Archetype relative to survey questions pertaining to positive emotions, negative emotions, and psychological states (Section 6.3). |

| Goal 4 Do the behavioural archetypes possess internal validity? | |

| Questions Do the participants respond affirmatively to questions pertaining to key characteristics of the behavioural archetype? Must participants respond to all questions affirmatively to be considered exponents of that behavioural archetype? To what extent does the continuum of human emotion influence variation to closed response questions? Is there evidence that any of the behavioural archetypes are significantly more or less valid than others? Were other dependent variables predictors of internal validity for the behavioural archetype? | Metrics The first five questions for each Behavioural Archetype were specifically designed to elicit this information. It was, therefore, possible to validate the extent to which each participant’s behaviours corresponded to key characteristics of the behavioural archetype. Statistics relating to response variation were found and analysed. Internal validity scores were found to be normally distributed and homogeneity of variance tests were undertaken. Subsequently, ANOVA was performed to identify any predictors of internal validity (Section 6.4). |

| Goal 5 Are the behavioural archetypes reliable? | |

| Questions Do the participants respond consistently? (With regard to questions pertaining to key characteristics of the behavioural archetype.) | Metrics The sum of participants’ internal validity scores for each Behavioural Archetype was found for each of five days of the study. These were plotted on a time series graph to enable any obvious visual trends to be seen. An essentially horizontal line is indicative of the stability of each behavioural archetype (Section 6.5). |

| Digital Response Equivalent | Questionnaire Response Data |

|---|---|

| 0 | Not Felt |

| 1 | Felt |

| 99 | No Response |

| Behavioural Archetype | N# | Total Diary Survey Questions | Internal Validity Questions | Positive Emotion Questions | Negative Emotion Questions | Psychological States Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 1 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Intimacy | 2 | 20 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Escapism | 3 | 15 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Narcissism | 4 | 17 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Discrepancy | 5 | 14 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Behavioural Archetype | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Secure | Intimacy | Escapism | Narcissism | Discrepancy | Total |

| Male | 13 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 26 |

| Female | 5 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 19 |

| Total | 18 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 45 |

| Age Group | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 3 | 10 | 13 |

| 25–34 | 16 | 7 | 23 |

| 35–44 | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Total | 26 | 19 | 45 |

| Statistics Test | Archetype Number | Participants Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-squared | 11.897 | 0.641 |

| Degree of Freedom | 4 | 1 |

| Asymptotic Significance | 0.018 | 0.423 |

| Behavioural Archetype (n) | Descriptive Statistic | Internal Characteristics Variable | Positive Emotions Variable | Negative Emotions Variable | Psychological States Variable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure (18) | Mean | 0.6452 | 0.6210 | 0.3565 | 0.3356 |

| N | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.16610 | 0.26943 | 0.24031 | 0.22968 | |

| Median | 0.7000 | 0.6333 | 0.3250 | 0.2933 | |

| Minimum | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.07 | |

| Maximum | 0.84 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Range | 0.51 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.93 | |

| Intimacy (11) | Mean | 0.6485 | 0.7010 | 0.3697 | 0.4737 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.25794 | 0.26562 | 0.16293 | 0.25010 | |

| Median | 0.6933 | 0.6667 | 0.3333 | 0.3333 | |

| Minimum | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.12 | |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.83 | |

| Range | 0.81 | 0.67 | 0.59 | 0.71 | |

| Escapism (4) | Mean | 0.6833 | 0.8917 | 0.6667 | 0.6792 |

| N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.06289 | 0.11345 | 0.26105 | 0.11003 | |

| Median | 0.6600 | 0.9167 | 0.6333 | 0.6833 | |

| Minimum | 0.64 | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.55 | |

| Maximum | 0.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | |

| Range | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.25 | |

| Narcissism (6) | Mean | 0.6667 | 0.7074 | 0.3389 | 0.3756 |

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.23491 | 0.23409 | 0.15117 | 0.10342 | |

| Median | 0.6067 | 0.7444 | 0.3333 | 0.3733 | |

| Minimum | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.23 | |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.53 | |

| Range | 0.67 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 0.31 | |

| Discrepancy (6) | Mean | 0.5778 | 0.9222 | 0.5148 | 0.5083 |

| N | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.28154 | 0.17470 | 0.21288 | 0.27543 | |

| Median | 0.5267 | 1.0000 | 0.5778 | 0.4167 | |

| Minimum | 0.25 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.25 | |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 0.95 | |

| Range | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.70 | |

| Total (45) | Mean | 0.6433 | 0.7163 | 0.4060 | 0.4282 |

| N | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | |

| Standard Deviation | 0.20529 | 0.25888 | 0.22467 | 0.23721 | |

| Median | 0.6400 | 0.7111 | 0.3500 | 0.3333 | |

| Minimum | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.07 | |

| Maximum | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Range | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.97 | 0.93 |

| Gender | Mean | N | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 0.6472 | 26 | 0.21981 | 0.6800 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Female | 0.6379 | 19 | 0.18936 | 0.6400 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.64 |

| Total | 0.6433 | 45 | 0.20529 | 0.6400 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Age Group | Mean | N | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 0.5774 | 13 | 0.17018 | 0.5600 | 0.25 | 0.80 | 0.55 |

| 25–34 | 0.6545 | 23 | 0.23858 | 0.6800 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| 35–44 | 0.7096 | 9 | 0.13949 | 0.6800 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.47 |

| Total | 0.6433 | 45 | 0.20529 | 0.6400 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Behavioural Archetype | Mean | N | Standard Deviation | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secure | 0.6452 | 18 | 0.16610 | 0.7000 | 0.33 | 0.84 | 0.51 |

| Intimate | 0.6485 | 11 | 0.25794 | 0.6933 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| Escapist | 0.6833 | 4 | 0.06289 | 0.6600 | 0.64 | 0.77 | 0.13 |

| Narcissist | 0.6667 | 6 | 0.23491 | 0.6067 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.67 |

| Discrepancy | 0.5778 | 6 | 0.28154 | 0.5267 | 0.25 | 1.00 | 0.75 |

| Total | 0.6433 | 45 | 0.20529 | 0.6400 | 0.19 | 1.00 | 0.81 |

| 5 Study Days | Secure | Intimacy | Escapism | Narcissism | Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 Mean | 24.5 | 29 | 34.25 | 24.33 | 24.4 |

| D2 Mean | 25.5 | 28.5 | 30.5 | 27.17 | 25.6 |

| D3 Mean | 22.44 | 28.13 | 31.5 | 27.5 | 26.6 |

| D4 Mean | 21.75 | 23.5 | 30.75 | 27.17 | 24.6 |

| D5 Mean | 20.63 | 25.88 | 32.75 | 24.17 | 27.4 |

| Overall Mean | 22.964 | 27.002 | 31.95 | 26.068 | 25.72 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altuwairiqi, M.; Jiang, N.; Ali, R. Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122136

Altuwairiqi M, Jiang N, Ali R. Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(12):2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122136

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltuwairiqi, Majid, Nan Jiang, and Raian Ali. 2019. "Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 12: 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122136

APA StyleAltuwairiqi, M., Jiang, N., & Ali, R. (2019). Problematic Attachment to Social Media: Five Behavioural Archetypes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(12), 2136. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16122136