“Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Lawsuit Cases of Gender Discrimination by Means of Stereotypes in the US and the European Union

1.2. Organizational Effects of Gender Stereotypes: A Meta-Analytic Literature Review

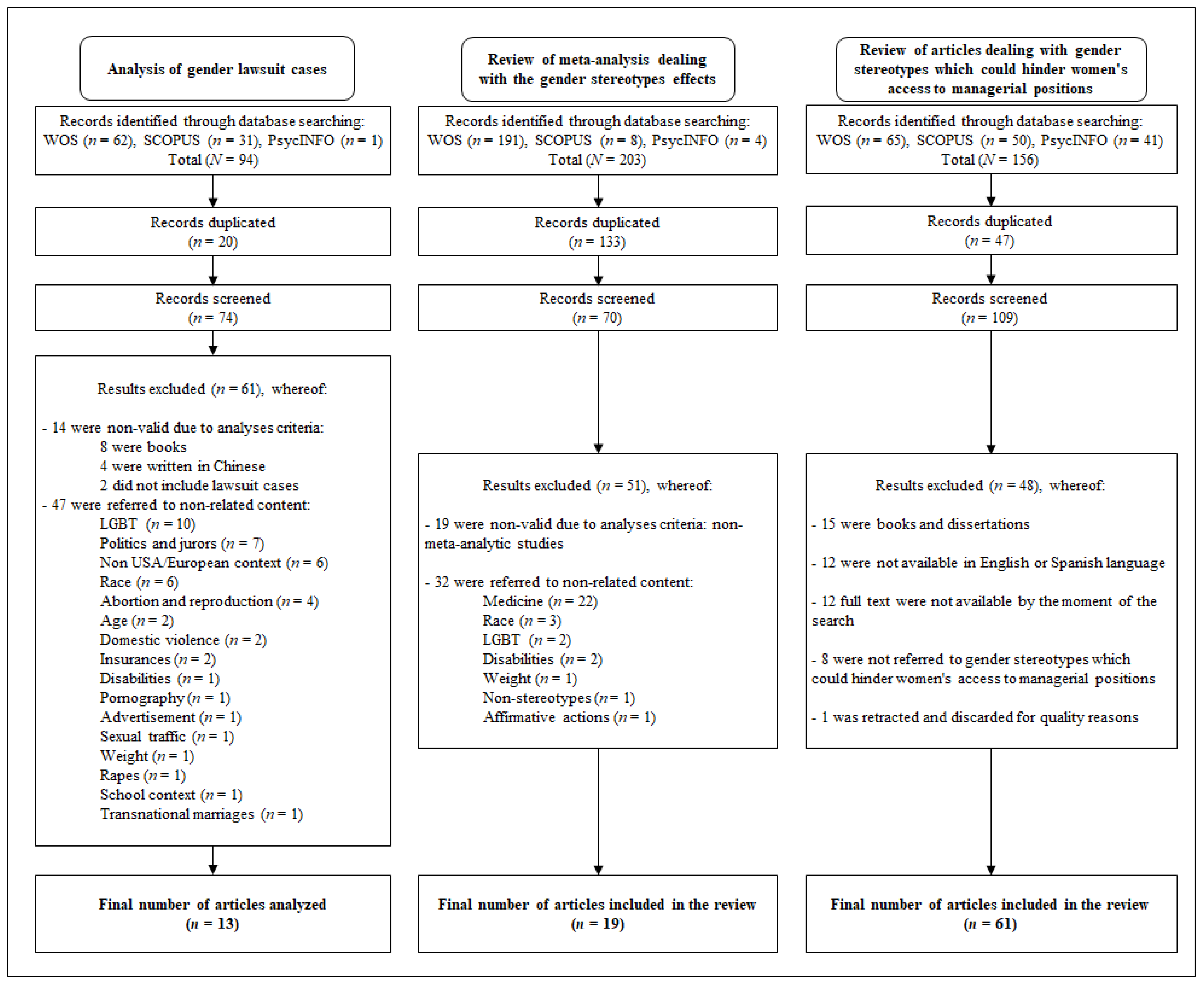

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Can We Overcome Stereotypes?

4.2. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- De Jonge, J.; Peeters, M.C.W. The Vital Worker: Towards Sustainable Performance at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2019, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labor Organization. Equality and Discrimination; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/equality-and-discrimination/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- International Labor Organization. A Quantum Leap for Gender Equality: For a Better Future of Work for All; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_674831/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- International Labor Organization. Report I(B)-Equality at Work: The continuing Challenge—Global Report under the Follow-Up to the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: http://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/100thSession/reports/reports-submitted/WCMS_154779/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 January 2019).

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting Well-Being, Meaningfulness, and Sustainability in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. Council Directive 2004/113/EC of 13 December 2004 Implementing the Principle of Equal Treatment between Men and Women in the Access to and Supply of Goods and Services; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Report on Equality between Women and Men in the EU; European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. Women at Work Trends; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Available online: http://www.ilo.org/gender/Informationresources/Publications/WCMS_457317/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- García-Izquierdo, A.L.; García-Izquierdo, M. Discriminación, igualdad de oportunidades en el empleo y selección de personal en España [Discrimination, equal employment opportunities and personnel selection in Spain]. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2007, 23, 111–138. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=231317574007 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- International Labor Organization. Decent Work; International Labor Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1919; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 27 March 2019).

- Heponiemi, T.; Kuusio, H.; Sinervo, T.; Elovainio, M. Job attitudes and well-being among public vs. private physicians: Organizational justice and job control as mediators. Eur. J. Public Health 2011, 21, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.J.; Noblet, A.J.; Rodwell, J.J. Promoting employee wellbeing: The relevance of work characteristics and organizational justice. Health Promot. Int. 2009, 24, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liljegren, M.; Ekberg, K. The associations between perceived distributive, procedural, and interactional organizational justice, self-rated health and burnout. Work Read. Mass 2009, 33, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drbohlav, D.; Dzúrová, D. Social Hazards as Manifested Workplace Discrimination and Health (Vietnamese and Ukrainian Female and Male Migrants in Czechia). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, W.M. Handbook on the Economics of Discrimination; Edward Elgar: Northampton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, A.B.; Dzubinski, L.M. Making the Invisible Visible: A Cross-Sector Analysis of Gender-Based Leadership Barriers. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2016, 27, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyness, K.S.; Grotto, A.R. Women and Leadership in the United States: Are We Closing the Gender Gap? Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 227–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdottir, U.D.; Christiansen, T.H.; Kristjansdottir, E.S. “It’s a Man Who Runs the Show”: How Women Middle-Managers Experience Their Professional Position, Opportunities, and Barriers. Sage Open 2018, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, J.L.; von Hippel, W. Stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1996, 47, 237–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, A.J.; D’Mello, S.D.; Sackett, P.R. A meta-analysis of gender stereotypes and bias in experimental simulations of employment decision making. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 128–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosette, A.S.; Akinola, M.; Ma, A. Subtle Discrimination in the Workplace. In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A.J., King, E.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, A.M.; von Glinow, M.A. Women and minorities in management. Am. Psychol. 1990, 45, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. Sex discrimination: The psychological approach. In Sex Discrimination in the Workplace: Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Crosby, F.J., Stockdale, M.S., Ropp, S.A., Eds.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 155–187. [Google Scholar]

- Siddaway, A.P.; Wood, A.M.; Hedges, L.V. How to Do a Systematic Review: A Best Practice Guide for Conducting and Reporting Narrative Reviews, Meta-Analyses, and Meta-Syntheses. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2019, 70, 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K. Guidance on conducting and reviewing systematic reviews (and meta-analyses) in work and organizational psychology. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, L.; Ritchie, J.; O’Connor, W. Analysis: Practices, principles and processes. In Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; SAGE: London, UK, 2003; pp. 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- The United States Congress. Civil Rights Act of 1964; The United States Congress: Fairbanks, AL, USA, 1964.

- European Union. Council Directive 76/207/EEC of 9 February 1976 on the Implementation of the Principle of Equal Treatment for Men and Women as Regards Access to Employment, Vocational Training and Promotion, and Working Conditions; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Women in S&P 500 Companies. 2018. Available online: http://www.catalyst.org/knowledge/women-sp-500-companies (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Fernández-Méndez, C.; Arrondo-García, R. Gender Diversity on Boards of Directors and Remuneration Committees: The Influence on Listed Companies in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development. OECD.Stat. Employment: Share of Employed Who are Managers, by Sex; Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2015; Available online: http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=54752# (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Fiske, S.T.; Bersoff, D.N.; Borgida, E.; Deaux, K.; Heilman, M.E. Social science research on trial: Use of sex stereotyping research in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 1049–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Enforcement and Litigation Statistics; US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/index.cfm (accessed on 10 December 2018).

- Moro, L. Igualdad de trato entre hombres y mujeres respecto a la promoción profesional en la jurisprudencia comunitaria: Igualdad formal versus igualdad sustancial (Comentario a las sentencias del TJCE de 17 de octubre de 1995, as. C-450/93, Kalanke y de 11 de noviembre de 1997, as. C-409/95, Marschall [Equality of treatment between men and women with respect to professional advancement in community jurisprudence: Formal equality versus substantial equality (Commentary on judgments of the ECJ of October 17, 1995, as. C.450/93, Kalanke and of November 11 of 1997, as. C-409/95, Marschall)]. Rev. Derecho Comunitario Eur. 1998, 2, 173–204. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/RDCE/article/view/48529 (accessed on 20 September 2018).

- Outtz, J.L. Can Scholarly Works on Discrimination Make a Practical Difference? In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A.J., King, E.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 419–422. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, J.S. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am. Psychol. 2005, 60, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, M.; Stone-Romero, E.F.; Coats, G. The effects of physical attractiveness on job-related outcomes: A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 431–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, K.G.; Reif, J.A.M.; Kaschner, T.; Brodbeck, F.C. Gender differences in the initiation of negotiations: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Walker, L.S.; Woehr, D.J. Gender and perceptions of leadership effectiveness: A meta-analysis of contextual moderators. J. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 99, 1129–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J.; Johnson, B.T. Gender and Leadership Style among School Principals: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Adm. Q. 1992, 28, 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Engen, M.L.; Willemsen, T.M. Sex and Leadership Styles: A Meta-Analysis of Research Published in the 1990s. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grijalva, E.; Newman, D.A.; Tay, L.; Donnellan, M.B.; Harms, P.D.; Robins, R.W.; Yan, T. Gender differences in narcissism: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 261–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C.; van Engen, M.L. Transformational, transactional, and laissez-faire leadership styles: A meta-analysis comparing women and men. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 569–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.P.; Sabat, I.E.; King, E.B.; Ahmad, A.; McCausland, T.C.; Chen, T. Isms and schisms: A meta-analysis of the prejudice-discrimination relationship across racism, sexism, and ageism. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 1076–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J.; Makhijani, M.G. Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoobler, J.M.; Masterson, C.R.; Nkomo, S.M.; Michel, E.J. The Business Case for Women Leaders: Meta-Analysis, Research Critique, and Path Forward. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 2473–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.-H.; Harrison, D.A. Glass Breaking, Strategy Making, and Value Creating: Meta-Analytic Outcomes of Women as CEOs and TMT members. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1219–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneid, M.; Isidor, R.; Li, C.; Kabst, R. The influence of cultural context on the relationship between gender diversity and team performance: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2015, 26, 733–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, A.M.; Eagly, A.H.; Mitchell, A.A.; Ristikari, T. Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 616–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badura, K.L.; Grijalva, E.; Newman, D.A.; Yan, T.T.; Jeon, G. Gender and leadership emergence: A meta-analysis and explanatory model. Pers. Psychol. 2018, 71, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-H.D.; Ryan, A.M. Does stereotype threat affect test performance of minorities and women? A meta-analysis of experimental evidence. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1314–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Makhijani, M.G.; Klonsky, B.G. Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 111, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.J.; Tiedens, L.Z. The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Treaty of Lisbon. Treaty of Lisbon Amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty Establishing the European Community (2007/C 306/01); Treaty of Lisbon: Lisbon, Portugal, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, E. La igualdad de género en el Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos: Un reconocimiento tardío en relación con el Tribunal de Justicia de la Unión Europea [Gender equality in the European Court of Human Rights: A belated recognition in relation to the Court of Justice of the European Union]. Rev. Esp. Derecho Const. 2015, 104, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J.; Elam, G. Designing and selecting samples. In Qualitative Research Practice. A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 77–108. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, D.; Borgida, E. Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychol. Public Policy Law 1999, 5, 665–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Karau, S.J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 109, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A. Kappa Fleiss Calculator. 2015. Available online: https://www.statstodo.com/CohenFleissKappa_Pgm.php (accessed on 10 September 2018).

- Duriau, V.J.; Reger, R.K.; Pfarrer, M.D. A Content Analysis of the Content Analysis Literature in Organization Studies: Research Themes, Data Sources, and Methodological Refinements. Organ. Res. Methods 2007, 10, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T., Jr.; McRae, R.R. Inventario de Personalidad Neo Revisado (NEO PI-R) [Neo Revised Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R)], 2nd ed.; TEA Ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.K.; Haslam, S.A. The Glass Cliff: Evidence that Women are Over-Represented in Precarious Leadership Positions. Br. J. Manag. 2005, 16, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.K.; Haslam, S.A.; Hersby, M.D.; Bongiorno, R. Think crisis–think female: The glass cliff and contextual variation in the think manager–think male stereotype. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A.; Phelan, J.E. Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, L.L.; Eagly, A.H. Gender, Hierarchy, and Leadership: An Introduction. J. Soc. Issues 2001, 57, 629–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.; Carli, L.L. Harvard Business Review. 2007. Available online: https://hbr.org/2007/09/women-and-the-labyrinth-of-leadership (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Kark, R.; Waismel-Manor, R.; Shamir, B. Does valuing androgyny and femininity lead to a female advantage? The relationship between gender-role, transformational leadership and identification. Leadersh. Q. 2012, 23, 620–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter, R.M. Men and Women of the Corporation; Basis Books: New York, NY, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, M. Stopgappers? The Occupational Trajectories of Men in Female-Dominated Occupations. Work Occup. 2018, 45, 283–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, L.D.; Aquino, K. Much Ado about Nothing? Observers’ Problematization of Women’s Same-Sex Conflict at Work. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 27, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staines, G.; Tavris, C.; Jayaratne, T.E. The queen bee syndrome. Psychol. Today 1974, 71, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jost, J.T.; Banaji, M.R.; Nosek, B.A. A Decade of System Justification Theory: Accumulated Evidence of Conscious and Unconscious Bolstering of the Status Quo. Polit. Psychol. 2004, 25, 881–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasi, G.; Jost, J.T. System Justification Theory and Research: Implications for Law, Legal Advocacy, and Social Justice. Calif. Law Rev. 2006, 94, 1119–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Kay, A.C. Exposure to Benevolent Sexism and Complementary Gender Stereotypes: Consequences for Specific and Diffuse Forms of System Justification. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seron, C.; Silbey, S.; Cech, E.; Rubineau, B. “I am Not a Feminist, but...”: Hegemony of a Meritocratic Ideology and the Limits of Critique Among Women in Engineering. Work Occup. 2018, 45, 131–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T.; Pelham, B.W.; Sheldon, O.; Ni Sullivan, B. Social inequality and the reduction of ideological dissonance on behalf of the system: Evidence of enhanced system justification among the disadvantaged. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, J.T. Outgroup favoritism and the theory of system justification: A paradigm for investigating the effects of socioeconomic success on stereotype content. In Cognitive Social psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Cognition; Moskowitz, G.B., Ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Valet, P. Social Structure and the Paradox of the Contented Female Worker: How Occupational Gender Segregation Biases Justice Perceptions of Wages. Work Occup. 2018, 45, 168–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéllar-Molina, D.; García-Cabrera, A.M.; Lucia-Casademunt, A.M. Is the Institutional Environment a Challenge for the Well-Being of Female Managers in Europe? The Mediating Effect of Work–Life Balance and Role Clarity Practices in the Workplace. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2018, 15, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P.; Fiske, S.T. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone-Romero, E.F.; Stone, D.L. How do organizational justice concepts relate to discrimination and prejudice? In Handbook of Organizational Justice; Greenberg, J., Colquitt, J.A., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaurn: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 439–467. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M. Sex bias in work settings: The lack of fit model. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Staw, B., Cummings, L., Eds.; JAI: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1983; pp. 269–298. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M.E. Sex stereotypes and their effects in the workplace: What we know and what we don’t know. J. Soc. Behav. Personal. 1995, 10, 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T. Intergroup biases: A focus on stereotype content. Soc. Behav. 2015, 3, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T.; Cuddy, A.J.C.; Glick, P.; Xu, J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 878–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldmeadow, J.; Fiske, S.T. System-justifying ideologies moderate status = competence stereotypes: Roles for belief in a just world and social dominance orientation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 37, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Cohen, B.P.; Zelditch, M. Status Characteristics and Social Interaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1972, 37, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Fişek, M.H. Diffuse Status Characteristics and the Spread of Status Value: A Formal Theory. Am. J. Sociol. 2006, 111, 1038–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Inf. Int. Soc. Sci. Counc. 1974, 13, 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior; Jost, J.T., Sidanius, J., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Schein, V.E. The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. J. Appl. Psychol. 1973, 57, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, V.E.; Davidson, M.J. Think Manager, Think Male. Manag. Dev. Rev. 1993, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L.A.; Moss-Racusin, C.A.; Phelan, J.E.; Nauts, S. Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 48, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welle, B.; Heilman, M. Formal and informal discrimination against women at work: The role of gender stereotypes. In Research in Social Issues in Management; Steiner, D., Gilliland, S.W., Skarlicki, D., Eds.; Information Age: Westport, CT, USA, 2005; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N. Gender Stereotypes. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devine, P.G. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 56, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forscher, P.S.; Devine, P.G. Breaking the prejudice habit: Automaticity and control in the context of a long-term goal. In Dual Process Theories of the Social Mind; Sherman, J., Gawronski, B., Trope, Y., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 468–482. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. The People Make the Place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Fernández-Salinero, S.; Topa, G. Sustainability in Organizations: Perceptions of Corporate Social Responsibility and Spanish Employees’ Attitudes and Behaviors. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.; Ma, J.; Bartnik, R.; Haney, M.H.; Kang, M. Ethical Leadership: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda. Ethics Behav. 2018, 28, 104–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquitt, J.A.; Conlon, D.E.; Wesson, M.J.; Porter, C.O.L.H.; Ng, K.Y. Justice at the millennium: A meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elango, B.; Paul, K.; Kundu, S.K.; Paudel, S.K. Organizational Ethics, Individual Ethics, and Ethical Intentions in International Decision-Making. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 543–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminke, M.; Ambrose, M.L.; Neubaum, D.O. The effect of leader moral development on ethical climate and employee attitudes. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2005, 97, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J.; van Dijke, M.; Mayer, D.M.; De Cremer, D.; Euwema, M.C. Can a leader be seen as too ethical? The curvilinear effects of ethical leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2013, 24, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resick, C.J.; Hargis, M.B.; Shao, P.; Dust, S.B. Ethical leadership, moral equity judgments, and discretionary workplace behavior. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, J.F.; Moscoso, S.; García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Anderson, N.R. Inclusive and Discrimination-Free Personnel Selection. In Shaping Inclusive Workplaces through Social Dialogue; Arenas, A., Di Marco, D., Munduate, L., Euwema, M.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscoso, S.; García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Bastida, M. A Mediation Model of Individual Differences in Attitudes toward Affirmative Actions for Women. Psychol. Rep. 2012, 110, 764–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Vilela, L.D.; Moscoso, S. Work analysis for personnel selection. In Employee Recruitment, Selection, and Assessment: Contemporary Issues for Theory and Practice; Current issues in work and organizational psychology; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Moscoso, S.; Ramos-Villagrasa, P.J. Reactions to the Fairness of Promotion Methods: Procedural justice and job satisfaction. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2012, 20, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ely, R.; Feldberg, A.C. Organizational Remedies for Discrimination. In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A.J., King, E.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 387–407. [Google Scholar]

- Salgado, J.F.; Moscoso, S. Selección de personal en la empresa y las AAPP: De la visión tradicional a la visión estratégica [Selection of personnel in organizations and the AAPP: From the traditional vision to the strategic vision]. Pap. Psicólogo 2008, 29, 16–24. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/html/778/77829103/ (accessed on 10 April 2018).

- Anderson, N.; Witvliet, C. Fairness Reactions to Personnel Selection Methods: An international comparison between the Netherlands, the United States, France, Spain, Portugal, and Singapore. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2008, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Izquierdo, A.L.; Ramos-Villagrasa, P.J.; Castaño, A.M. e-Recruitment, gender discrimination, and organizational results of listed companies on the Spanish Stock Exchange. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2015, 31, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladge, J.J.; Humberd, B.K.; Baskerville Watkins, M.; Harrington, B. Updating the Organization MAN: An Examination of Involved Fathering in the Workplace. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Science 1974, 185, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M.E.; Caleo, S. Gender Discrimination in the Workplace. In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A.J., King, E.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Gaissmaier, W. Heuristic Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2011, 62, 451–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, J.; Kleinlogel, E.P. Employment Discrimination as Unethical Behavior. In The Oxford Handbook of Workplace Discrimination; Colella, A.J., King, E.B., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 59–72. [Google Scholar]

- Casad, B.J.; Bryant, W.J. Addressing Stereotype Threat is Critical to Diversity and Inclusion in Organizational Psychology. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Assessment Service Delivery—Procedures and Methods to Assess People in Work and Organizational Settings—Part 1: Requirements for the Client; ISO 10667-1:2011; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. Assessment Service Delivery—Procedures and Methods to Assess People in Work and Organizational Settings—Part 2: Requirements for Service Providers; ISO 10667-2:2011; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, J.T.; Fine, E.; Pribbenow, C.M.; Handelsman, J.; Carnes, M. Searching for Excellence & Diversity: Increasing the Hiring of Women Faculty at One Academic Medical Center. Acad. Med. 2010, 85, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, A.J.; Vaque-Manty, D.L.; Malley, J.E. Recruiting female faculty members in science and engineering: Preliminary evaluation of one intervention model. J. Women Minor. Sci. Eng. 2004, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galinsky, A.D.; Moskowitz, G.B. Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kite, M.E.; Deaux, K.; Haines, E.L. Gender Stereotypes. In Psychology of Women: A Handbook of Issues and Theories; Denmark, F.L., Paludi, M.A., Eds.; Praeger Publishers: Westport, CT, USA, 2008; pp. 205–236. [Google Scholar]

- Guion, R.M. Assessment, Measurement, and Prediction for Personnel Decisions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tippins, N.T. Adverse Impact in Employee Selection Procedures From the Perspective of an Organizational Consultant. In Adverse Impact; Outtz, J.L., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 201–225. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, D.A.; Burdfield-Steel, E.; Potvin, J.M.; Heap, S.M. Diversity begets diversity: A global perspective on gender equality in scientific society leadership. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, H.S.; Morris, M.L.; Atchley, E.K. Constructs of the Work/Life Interface: A Synthesis of the Literature and Introduction of the Concept of Work/Life Harmony. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2010, 10, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Council Directive 2014/124/EU of 7 March 2014 on Strengthening the Principle of Equal Pay between Men and Women through Transparency; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. Guidance on Social Responsibility; ISO 26000:2010; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhoven, A.H.; Russo, P.; Land-Zandstra, A.M.; Saxena, A.; Rodenburg, F.J. Gender Stereotypes in Science Education Resources: A Visual Content Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, L.; Stuart-Fox, D.; Hauser, C.E. The gender gap in science: How long until women are equally represented? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, K.M.M.; Asadullah, M.N. Gender stereotypes and education: A comparative content analysis of Malaysian, Indonesian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi school textbooks. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, S.J.; Logel, C.; Davies, P.G. Stereotype Threat. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2016, 67, 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlova, M.A.; Weber, S.; Simoes, E.; Sokolov, A.N. Gender Stereotype Susceptibility. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case | No. | Description | Court Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion | |||

| Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins 1989 | 6 | Ms. Hopkins was refused for partnership despite her good economical results, arguing she was aggressive. | The court considered that refusing the partnership of Ms. Hopkins constituted gender discrimination. (+) |

| Schlesinger v. Ballard 1975 | 2 | A man complained against a navy’s promotion policy that allows longer time in rank for female officers. | The court held that the different treatment results from the different opportunities for professional service. (+) |

| Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney 1979 | 2 | A woman was ranked below male veterans who had lower scores due to the preference to honorably discharged veterans. | The court found no discriminatory purpose. (−) |

| Texas Dept. of Community Affairs v. Burdine 1981 | 2 | A woman applied for a supervisor position, but a male employee from another division was hired. | The court held that the decision was not based on unlawful criteria and the company was not required to hire female applicants equally qualified. (−) |

| Wal-Mart v. Dukes 2011 | 2 | Several women filed a class action lawsuit for experiencing sex discrimination in pay and promotion. | The court viewed the claims as lacking the necessary commonality to support class certification. (−) |

| Johnson v. Transportation Agency 1987 | 1 | Mr. Johnson was passed over for a promotion in favor of Ms. Joyce on the basis of an affirmative action plan. | The court considered that the Transportation Agency appropriately took into account Joyce’s sex as determinant for the promotion. (+) |

| Motherhood | |||

| Young v. UPS 2015 | 2 | A woman was forced to take an unpaid leave, as the company policy required being able to lift up more pounds than the pregnant complainant was advised to. | The court established the criteria unconstitutional. (+) |

| Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp. 1971 | 1 | A complaint against an employer who refused to hire women, but not men, with young children. | The court held that an employer could not refuse to hire females with young children. (+) |

| Wimberly v. Missouri Labor and Industrial Relations Commission 1987 | 1 | A woman complained for not being rehired after taking pregnancy leave, alleging she had left work voluntarily and without good cause. | The court declared that the denial of her unemployment compensation was not based upon her pregnancy and therefore was not illegal. (−) |

| Gender segregated domains | |||

| Mississippi University for Women v. Hogan 1982 | 4 | A qualified applicant was denied the admission to the Mississippi University for Women School of Nursing on the basis of sex. | The court found gender discrimination. (+) |

| Bradwell v. Illinois 1873 | 2 | Lawyer Mira Bradwell was refused a license to practice law because she was a woman. | The court held that women did not have the right to practice law. (−) |

| Dothard v. Rawlinson 1977 | 2 | A complaint against excluding women from positions as prison guards in maximum security facility. | The court held that having women as prison guards would create security and safety problems. (−) |

| U.S. v. Virginia 1996 | 2 | A complaint against the exclusion of women from a military college. | The court held that male-only admissions policy was unconstitutional. (+) |

| Vorchheimer v. School District of Philadelphia 1977 | 1 | A complaint against a public high school restricted to males. | The court held the gender classification. (−) |

| Rostker v. Goldberg 1981 | 1 | A complaint against male only military registration. | The court held the only male military registration. (−) |

| Washington v. Gunther 1981 | 1 | Female county prison guards complained for being paid less than male guards. | The court held that the wage differential is based on a differential based on any other factor than sex. (−) |

| UAW v. Johnson Controls, Inc. 1991 | 1 | A complaint against the prohibition of women, except for infertile women, from engaging in tasks with lead exposure. | The court held that excluding women was sex discrimination. (+) |

| United States v. Burke 1992 | 1 | A case about increasing the salaries of employees only in male dominated pay schedules. | The court held that discrimination constituted a tort-like injury to respondents. (+) |

| Case | No. | Description | Court Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promotion | |||

| Kalanke v. Bremen 1995 | 2 | Mr. Kalanke was initially proposed for a promotion, however, Ms. Glissman (holding equal qualifications for the job) was finally promoted. | The sentence considered unlawful a positive discrimination action favoring the promotion of a woman. (−) |

| Marschall v. Land Nordrhein-Westfalen 1997 | 1 | A female candidate with the same merits as Mr. Marschall was proposed for a promotion instead of him because of an affirmative action. | The sentence supported the decision of the Kalanke’s case, although the legality of positive discrimination was recognized. (−) |

| Motherhood | |||

| Petrovic v. Austria 1998 | 4 | A father was denied parental leave on the basis that only mothers were allowed. | The court denied the parental leave of the father. (−) |

| Markin v. Russia 2012 | 4 | Russian serviceman who was responsible for his children claimed equal parenting rights as women. | The court held that maternity leave to mothers not fathers perpetuates gender stereotypes hindering women’s careers and men’s family life. (+) |

| Roca Álvarez v. Sesa Start España ETT SA 2010 | 1 | Roca Álvarez requested the right to take the parental leave, but his request was refused because the mother of his child was self-employed. | Refusing the father’s leave when the mother was self-employed perpetuated the role of women as the main responsible for parental duties. (+) |

| Gender segregated domains | |||

| Karlheinz Schmidt v. Germany 1994 | 1 | A case about fire brigade duty that was compulsory for men only, arguing the protection of women. | The court found a violation of the Convention. (+) |

| Emel Boyraz v. Turkey 2014 | 1 | A woman was denied a position as a security officer in the state-run electricity company because she was a woman. | The court stated that work night shifts and physical force requirements could not in itself justify the difference in treatment between men and women. (+) |

| Reference | Results |

|---|---|

| Leadership styles | |

| Eagly AH, Karau SJ, Johnson BT 1992 | Women were more democratic and less autocratic than men, however there were no differences for either interpersonal style or interpersonal versus task style. |

| Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC, van Engen ML 2003 | Female leaders were more transformational than male leaders and also engaged in more contingent reward; whereas men manifest greater transactional active and passive leadership and laissez-faire approaches. |

| Van Engen ML, Willemsen TM 2004 | Men tended to use the traditionally masculine styles and women the traditionally feminine styles: women tended to use the stereotypical feminine styles democratic-versus-autocratic and transformational leadership styles. However, no evidence was found for sex differences in interpersonal, task-oriented, and transactional leadership. |

| Leadership idea | |

| Eagly AH, Makhijani MG, Klonsky BG 1992 | There was a small overall tendency to evaluate female leaders less favorably than male leaders, especially when female leadership was carried out in stereotypically masculine styles, in male-dominated roles, and when the evaluators were men. |

| Koenig AM, Eagly AH, Mitchell AA, Ristikari T 2011 | Masculinity of leader stereotypes was found: (a) male-leader similarity; (b) greater agency than communion; and (c) greater masculinity. |

| Koch AJ, D’Mello SD, Sackett PR 2015 * | Men were preferred for male-dominated jobs, and male raters exhibited greater gender-role congruity bias than did female raters for male-dominated jobs. |

| Badura KL, Grijalva E, Newman DA, Yan TT, Jeon G 2018 | Men tended to emerge in leadership roles more often than did women. Moreover, men tended to possess higher levels of agentic traits, whereas women tended to possess higher levels of communal traits. |

| Effectiveness and performance | |

| Eagly AH, Karau SJ, Makhijani MG 1995 | Male and female leaders were equally effective. However, effectiveness comparisons favored men for first-level leadership; and female leaders fared better in feminine expected roles such as education, whereas male leader fared better in masculine expected roles such as military. |

| Paustian-Underdahl SC, Walker LS, Woehr DJ 2014 | Men and women did not differ in perceived leadership effectiveness when all leadership contexts are considered. |

| Schneid M, Isidor R, Li C, Kabst R 2015 * | A negative relationship was found between gender diversity and contextual performance, although no relationship was found with task performance. However, gender diversity has a significant negative relationship with task performance in countries with low gender egalitarianism. |

| Jeong SH, Harrison DA 2017 | Female presence in CEO positions was positively related to long-term financial performance and negatively related to short-term market returns; whereas female presence in top management teams was positively related to long-term financial performance but not to short term market returns. |

| Hoobler JM, Masterson CR, Nkomo SM, Michel EJ 2018 | There was a positive association between having more women on boards of directors and overall financial performance. |

| Personality and individual characteristics | |

| Hyde JS 2005 * | There were small or non-differences regarding cognitive variables, verbal or nonverbal communication, social or personality variables, wellbeing, motor behaviors, and moral reasoning. |

| Grijalva E et al., 2015 * | Men tended to be more narcissistic than women, however, men and women did not differ on vulnerable (low self-esteem, neuroticism, and introversion) narcissism. |

| Williams MJ, Tiedens LZ 2016 | Dominance expressed explicitly affected women’s likability, whereas implicit forms of dominance did not. Furthermore, dominant women were found to have worse outcomes on dimensions such hireability. Nonetheless, non significant differences were found regarding men’s and women’s perceived competence. |

| Kugler KG, Reif JAM, Kaschner T, Brodbeck FC 2018 * | Women were less likely to initiate negotiations than men. However, gender differences were smaller for low situational ambiguity and situational cues, consistent with the female gender role. |

| Other criteria: physical appearance, stereotype threat, and sexism | |

| Hosoda M, Stone-Romero EF, Coats G 2003 * | Attractive people were found to be better than unattractive on job-related outcomes, obtaining similar values for women and men. |

| Nguyen H-HD, Ryan AM 2008 * | The overall performance of women stereotyped test takers might suffer from a situational stereotype threat. |

| Jones KP et al., 2017 * | There was no relationship between sexism and overall workplace discrimination. |

| Journal | Number of Articles Retrieved Per Journal | Total of Articles Retrieved |

|---|---|---|

| Gender in Management: An International Journal | 7 | 7 |

| Gender, Work & Organization | 4 | 4 |

| Journal of Managerial Psychology Psychology of Women Quarterly | 3 | 6 |

| Higher Education Human Relations Journal of Applied Psychology Journal of Business and Psychology SAGE Open | 2 | 10 |

| African Journal of Business Management Applied Psychology Australian Journal of Public Administration British Journal of Management British Journal of Social Psychology Estudios de Psicología European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology Human Resource Development International Human resources for health International Journal of Conflict Management International Journal of Health Policy and Management Journal of Nursing Management International Journal of Emerging Markets International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship International Journal of Hospitality Management Journal of Applied Social Psychology Journal of Business Ethics Journal of Business Research Journal of International Business Studies Journal of Management Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development Negotiation and Conflict Management Research Organizational Dynamics Organization Science Psychological Bulletin Psykhe Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho Scandinavian Journal of Management Social Forces Strategic Management Journal Swiss Journal of Psychology The History of the Family The Leadership Quarterly The Spanish Journal of Psychology | 1 | 34 |

| Total | 61 |

| Domains, Categories, and Subcategories of Gender Stereotypes | Units of Analysis Retrieved from the Analyzed Journal Articles | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % | |

| Descriptive stereotypes | ||

| 1. Personality traits | 408 | 54.33 |

| 1.1. Agreeableness | 137 | 33.58 |

| 1.2. Extraversion | 72 | 17.65 |

| 1.3. Conscientiousness | 68 | 16.67 |

| 1.4. Neuroticism | 50 | 12.25 |

| 1.5. Openness | 24 | 5.88 |

| No subcategory * | 57 | 13.97 |

| 2. Abilities | 230 | 30.63 |

| 2.1. Applied | 205 | 89.13 |

| 2.2. Basic | 12 | 5.22 |

| No subcategory * | 13 | 5.65 |

| 3. Leadership styles | 79 | 10.52 |

| 4. Motivation | 21 | 2.79 |

| 5. Physical appearance | 13 | 1.73 |

| Total | 751 | 65.30 |

| Prescriptive stereotypes | ||

| 1. Adopting stereotypical gender characteristics | 146 | 36.59 |

| 1.1. Masculine | 65 | 44.52 |

| 1.2. Feminine | 51 | 34.93 |

| 1.3. Androgynous | 13 | 8.90 |

| No subcategory * | 17 | 11.64 |

| 2. Roles | 114 | 28.57 |

| 2.1. Family care | 59 | 51.75 |

| 2.2. Working home | 30 | 26.32 |

| No subcategory * | 25 | 21.93 |

| 3. Status | 103 | 25.81 |

| 4. Peer rating | 36 | 9.02 |

| Total | 399 | 34.69 |

| Theory | Discrimination Criterion |

|---|---|

| General discrimination theories | |

| -Social Identity Theory -Group-Based Differential Model | A. The categorization of people into in/out-groups |

| -Status Characteristics Theory -Stereotype Content Model | B. The categorization of people regarding the perceived status and/or warmth |

| Gender discrimination theories | |

| -Lack of Fit Model -Think Manager-Think Male Theory -Role Congruity Theory of Prejudice Toward Female -Status Incongruity Hypothesis | C. A perceived lack of fit between the women’s attributes and roles and the managerial requirements |

| -Ambivalent Sexism Theory | D. Positive and negative feelings about women |

| Gender Stereotype | Psychosocial Theories of Gender Discrimination |

|---|---|

| Descriptive stereotypes | |

| 1. Personality traits (i.e., agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness) | GBDM, LFM, RCT, SCM, SIT, TMTM |

| 2. Abilities (i.e., applied, basic) | GBDM, LFM, SCM, SCT, SIT, TMTM |

| 3. Leadership styles | GBDM, LFM, SCM, SCT, SIT, TMTM |

| 4. Physical appearance | AST, GBDM, LFM, SIT, TMTM |

| 5. Motivation | GBDM, LFM, SIT, TMTM |

| Prescriptive stereotypes | |

| 1. Adopting stereotypical gender characteristics (i.e., masculine, feminine, androgynous) | LFM, RCT, SCM, SIH, TMTM |

| 2. Roles (i.e., family care, working home) | AST, LFM, RCT, SCM, SCT, SIH, TMTM |

| 3. Status | LFM, SCM, SCT, SIH, TMTM |

| 4. Peer rating | LFM, SCM, TMTM |

| Guiding Principles |

|---|

| Guiding principle 1: Assessment processes based on job analysis would buffer the influence of descriptive stereotyped beliefs. |

| Guiding principle 2: Assessment models should integrate the whole personal working characteristics for preventing the influence of stereotyped beliefs. |

| Guiding principle 3: High reliable and valid assessment methods are less liable to be influenced by stereotyped beliefs. |

| Guiding principle 4: Job postings and assessment methods which avoid gender-type language and personal questions lessen the impact of prescriptive stereotyped beliefs. |

| Guiding principle 5: Gender balanced hiring committees would entail better opportunities for avoid the influence of stereotyped beliefs in decision-making. |

| Guiding principle 6: Training on how to identify and modify stereotyped beliefs would be helpful for the promotion of equality in the workplace. |

| Area | Good Practices | Stereotypes |

|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | -Analyze the percentage of women inside the candidate pool looking for balancing the number of women and men. | MO, RO, ST |

| Personnel selection and assessment | Before the assessment: | |

| -Provide evidence of bias free assessment and criterion oriented methods before their use. | PE, AB, PH | |

| -Carry out workshops for decision-makers in order to identify gender stereotypes. | ALL | |

| -Inform decision-makers about the benefits of gender diverse managerial teams. | ALL | |

| During the assessment: | ||

| -Make decisions from the perspective taking approach. | MO, PR | |

| -Use blind CV with no information about the gender of the candidates. | ALL | |

| -Carry out structured behavioral interviews and apply valid and reliable instruments and methods based on competencies. | PE, AB, LE, MO | |

| -Provide the explanation of the competencies of the selected candidate. | PE, AB, LE, PH, MO | |

| -Balance the presence of women and men in the decision-making tribunal. | AD, RO, ST, PR | |

| After the assessment: | ||

| -Compare the presence of women and men regarding departments and levels. | RO, ST | |

| -Compare retributions of women and men. | PE, AB, ST | |

| -Establish a reference number of women in higher positions to achieve in long-term. | MO, RO, ST | |

| -Empirical assessment of adverse impact. | PE, AB, PH, AD, RO, ST | |

| -Assess perceived barriers for the professional advancement of women. | ALL | |

| Organizational culture and relationships with stakeholders | -Establish gender diversity as an added value inside the good governance code. -Create and promote an equality label. -Require the equality label for establishing relationships with stakeholders and for the award of public contracts. -Establish a gender inclusive communication code. | ALL |

| Work–family conciliation and professional development | -Establish equal parental leave for women and men. | AD, RO |

| -Avoid meetings both early in the morning and late in the evening. | RO | |

| -Implement non-lineal professional career development. | MO, RO | |

| -Establish mentoring programs for women in pre-managerial positions. | LE, MO, ST | |

| Other areas | -Verify that both retributions of women and men are equal. | AB, ST, PR |

| -Implement an advisory service for women inside the organizations. | MO, RO, PR |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castaño, A.M.; Fontanil, Y.; García-Izquierdo, A.L. “Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101813

Castaño AM, Fontanil Y, García-Izquierdo AL. “Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(10):1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101813

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastaño, Ana M., Yolanda Fontanil, and Antonio L. García-Izquierdo. 2019. "“Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16, no. 10: 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101813

APA StyleCastaño, A. M., Fontanil, Y., & García-Izquierdo, A. L. (2019). “Why Can’t I Become a Manager?”—A Systematic Review of Gender Stereotypes and Organizational Discrimination. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 1813. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101813