Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Involvement

2.2. Perceived Value

2.3. Leisure Benefits

2.4. Recommendation Intention

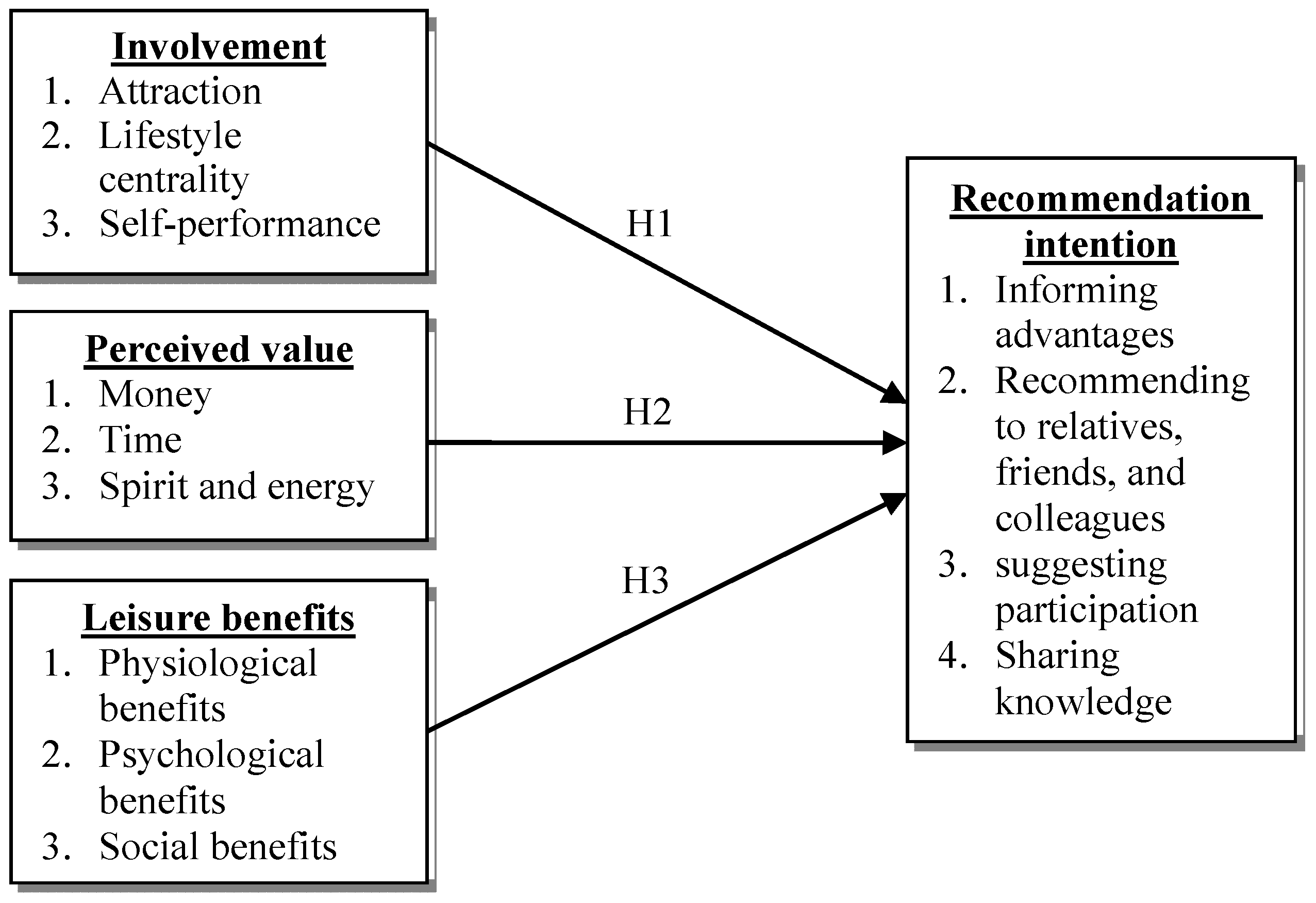

2.5. Research Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Hypothesis and Framework

3.2. Research Instrument

3.3. Research Subject and Data Collection

3.4. Statistical Analysis Methods

4. Research Results

4.1. Analysis of Sample Basic Data

4.2. Reliability and Validity Analysis of Scale

4.3. Correlation Analysis

4.4. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, C.J.; Yeh, T.M.; Lin, Y.L. Exercise and Leisure! The Effect of Belly Dance Participants’ Leisure Involvement on Leisure Benefits. J. Sport Leis. Hosp. Res. 2016, 11, 57–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Heo, J.M.; Dvorak, R.; Han, A. Benefits of Leisure Activities for Health and Life Satisfaction among Western Migrants. Ann. Leis. Res. 2018, 21, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.M.; Chang, Y.C.; Lai, M.Y. The Relationships among Leisure Experience, Leisure Benefits and Leisure Satisfaction of YouBike Users. J. Sport Leis. Hosp. Res. 2017, 12, 67–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.J.; Wray, L.; Lin, Y. Social Relationships, Leisure Activity, and Health in Older Adults. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, C.L.; Huang, C.C. A Study of Different Types of Leisure on Mental and Physical Health and Leisure Benefits. J. Leis. Tour. Sport Health 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, Y.T.; Ho, W.H.; Li, K.S.; Liu, Y. The Analysis of Motor Response in Karate Roundhouse Kick. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. Chin. Cult. Univ. 2003, 1, 65–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.Y.; Tsai, C.L. Discussion of Karate Exercise on Balance Ability of the Elderly. Chung Yuan Phys. Educ. J. 2016, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barlas, A.; Mantis, K.; Katelios, A. Achieving positive word-of-mouth communication: The role of perceived service quality in the context of Greek ski centres. World Leis. J. 2010, 52, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, J. Corporate Reputation: A research agenda using strategy and stakeholder literature. Bus. Soc. 2002, 41, 415–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, J.L.M. The effects of service quality, Perceived value and customer satisfaction on behavioral intentions. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2000, 6, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Petrick, J.F.; Backman, S.J. An examination of the determinants of golf travelers’ satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannel, R.C.; Stynes, D.J. A Retrospective: The Benefits of Leisure. In Benefits of Leisure; Driver, B.L., Brown, P.J., Peterson, G.L., Eds.; Venture Publishing: Stage College, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 461–473. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Benefits of Leisure: A Social Psychological Perspective. In Benefits of Leisure; Driver, B.L., Brown, P.J., Peterson, G.L., Eds.; Venture Publishing: Stage College, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Celsi, R.L.; Olson, J.C. The role of involvement in attention and comprehension processes. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.L. Perspectives on involvement: Current problems and future directions. In Advance in Consumer Research; Kinnear, T.C., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1984; Volume 11, pp. 216–217. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, G.; Kapferer, J.N. Measuring consumer involvement profiles. J. Mark. Res. 1985, 102, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcintyre, N. The personal meaning of participation: Enduring involvement. J. Leis. Res. 1989, 21, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.T.; Mowen, A.J. An examination of the leisure involvement-agency commitment relationship. J. Leis. Res. 2005, 37, 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannell, R.C.; Iso-Ahola, S. Psychological nature of leisure and tourism experience. Ann. Tour. Res. 1987, 14, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.B.; Leibbrandt, S.; Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Dimanche, F. Leisure involvement revisited: Conceptual conundrums and measurement advances. J. Leis. Res. 1997, 29, 245–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, M.P. Opinion leadership, Enduring involvement and characteristics of opinion leaders: A moderating or mediating relationship. Adv. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Scott, D.; Crompton, J.L. An exploration of the relationships among social psychological involvement, Behavioral involvement, Commitment, and future intentions in the context of bird watching. J. Leis. Res. 1997, 29, 320–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varki, S.; Wong, S. Consumer involvement in relationship marketing of service. J. Serv. Res. 2009, 6, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.N.; Wu, S.N. A study on Tennis Players’ Leisure Motivation, Leisure Involvement, and Subjective Well-being. J. Sport Recreat. Res. 2013, 7, 99–120. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.M.; Chang, T.D. A Study on the Relationships among Leisure Involvement, Leisure—Family Conflict, and Happiness of Bicycle Recreationists. Rev. Leis. Sport Health 2011, 2, 144–163. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe, K.B.; Krishnan, R. Perceived Quality: How Consumers View Stores and Merchandise; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R. Mental accounting consumer choice. Mark. Sci. 1985, 4, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B. The Effect of Brand and Price Information on Subjective Product Evaluations. Adv. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, Quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, W.B.; Monroe, K.B.; Grewal, D. Effects of price, Brand, and store information on buyers product evaluations. J. Mark. Res. 1991, 28, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, B.T. Managing Customer Value; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, J.L.M. Customer satisfaction, Service quality and perceived value: An integrative model. J. Mark. Manag. 2004, 20, 897–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer trust, Value, and loyalty in relational exchange. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Brand Portfolio Strategy; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fandos, J.C.; Sanchez, J.; Moliner, M.A.; Monzonis, J.L. Customer perceived value in banking service. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2006, 24, 266–283. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, B.L.; Brown, P.J.; Peterson, G.L. Benefits of Leisure; Venture Publishing, Inc.: State College, PA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bammel, G.; Burrus-Bammel, L.L. Leisure and Human Behavior; Wm. C. Brown Company Publisher: Dubuque, IA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Mannell, R.C.; Kleiber, D.A. A Social Psychology of Leisure; Venture Publishing: State College, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki, Y. Leisure and Quality of Life in An International and Multicultural Context: What Are Major Pathways Linking Leisure to Quality of Life? Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 233–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D. Leisure based social support, Leisure dispositions and health. J. Leis. Res. 1993, 25, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegenthaler, K.L. Health benefits of leisure. Parks Recreat. 1997, 32, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fenech, A. The benefits and barriers to leisure occupations. Neuro Rehabilit. 2008, 23, 295–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wankel, L.M.; Berger, B.G. Their personal and social benefits of sport and physical activity. In Benefits of Leisure; Driver, B.L., Brown, P.J., Peterson, G.L., Eds.; Venture Publishing: Stage College, PA, USA, 1991; pp. 121–144. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, J. Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. J. Mark. Res. 1967, 4, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bone, P.F. Word-of-mouth effects on short-term and long-term product judgments. J. Bus. Res. 1995, 32, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E.W. Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. J. Serv. Res. 1998, 1, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior; Harcourt College Publishers: Orlando, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 4, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Thorsten, K.P.; Gwinner, G.W.; Dwayne, D.G. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodker, M.; Browning, D. Beyond destinations: Exploring tourist technology design spaces through local-tourist interactions. Digit. Creativity 2012, 23, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, S.W.; Goldsmith, R.E.; Pan, B. Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Schwartz, E. What drives immediate and ongoing word-of-mouth. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. Attitude change, Media and word-of-mouth. J. Advert. Res. 1971, 11, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, W.L. Consumer Behavior; Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, J.; Chew, P. The effects of incentives deal proneness, satisfaction and tie strength on word-of-mouth behavior. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2002, 13, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, P.M.; Kardes, F.R.; Kim, J. Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information of persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. J. Consum. Res. 1991, 17, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, G. The service quality-loyalty relationship in retail services: Does commitment matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2005, 12, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, J. Customer Loyalty; Simon and Schuster Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, N. Loyal: Customer Relationship Management in the New Era of Internet Marketing; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.Y.; Shankar, V.; Erramilli, M.K.; Murthy, B. Customer value, Satisfaction, Loyalty, and switching costs: An illustration from a business-to-business service context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, T.G. Assessing the effects of quality, Value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.C.; Lin, Y.S.; Koa, S.F. The Study of the Relationship among Karting Drivers’ Involvement, Flow Experience and Behavioral Intentions. J. Taiwan Soc. Sport Manag. 2009, 9, 31–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gronholdt, L.; Martensen, A.; Kristensen, K. The relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: Cross-industry differences. Total Qual. Manag. 2000, 11, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.T.; Chuang, Y.N.; Sun, M.L. A Study of Involvement, Satisfaction, Loyalty and Sport Tourism of Spectators of Professional Baseball in ROC. J. Sport Recreat. Manag. 2010, 7, 70–91. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.R.; Wang, K.W.; Lai, S.S. Spectator Involvement, Team Identification Aimed at Satisfaction, Loyalty of the Impact Study: The case of Super Basketball League in Taiwan. J. Phys. Educ. Leis. Ling Tung Univ. 2008, 6, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, Perceived value, Satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Robertson, R.; Wu, C.L. The effect of airline service quality on passengers’ behavioral intentions: A Korean case study. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2004, 10, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.G.; Tsai, W.H.; Lin, C.W. Participation Behavioral Model for Tennis Tournaments. J. Sport Recreat. Manag. 2014, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang, J.C.; Tien, L.; Chung, C.C. The Relationship among Involvement, Perceived Value and Behavioral Intentions of the Yunlin Music Festival. J. Leis. Exerc. 2010, 9, 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, G.R.; Hammond, K. Customer Loyalty and Customer Loyalty Programs MD Uncles. J. Consum. Mark. 2003, 20, 294–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.K.; Park, M.C.; Jeong, D.H. The effects of customer satisfaction and switching barrier on customer loyalty in Korean mobile telecommunication services. Telecommun. Policy 2004, 28, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.K.; Sung, Y.F. Push and Pull Motivations, Perceived Value, Satisfaction and Loyalty—The Case of Foreign Tourists Travel to Taiwan. J. Tour. Travel Res. 2011, 6, 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.W.; Lai, W.J.; Chang, C.H. Relationship between tourism image, travel satisfaction and word-of-mouth recommendations—A case of 2013 Hsinchu Taiwan lantern festival. J. Sport Leis. Hosp. Res. 2013, 8, 106–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. The research of service quality, tourist satisfaction, recreation benefit and after tour behavior—The case of Kaohsiung dragon boat race activity. J. Hosp. Tour. 2011, 8, 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Pi, L.L.; Hsiao, C.H.; Chen, L.H.; Lin, H.H. Leisure benefits, Activity Satisfaction, and Loyalty of DDM Walking. J. Taiwan Soc. Sport Manag. 2014, 13, 317–338. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.D.; Chen, K.Y.; Lee, S.H. A Study on Causal Relationships among Recreation Involvement, Place Dependence, and Place Identity: A Case of Recreation Bikers at Tong-Fon Bikeway Green Corridor. J. Outdoor Recreat. Study 2008, 21, 27–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.L.; Lin, A.T. A Study of the Relationship among Mountain Climbing Participants’ Involvement, Flow Experience and Well-being. J. Taiwan Soc. Sport Manag. 2011, 11, 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Liao, L.C. A Study of Tourist, on Travel Images, Qualities, Perceived Value, and Revisiting Willingness in Lukang. J. Leis. Recreat. Ind. Manag. 2010, 3, 62–80. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.H. A Study on the Relation between the Leisure Involvement of College Students Engaged in In-line Hockey and the Benefit of Serious Leisure. Leis. Ind. Res. 2010, 8, 68–82. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.M.; Chao, C.Y.; Lin, K.Y. A Study of Leisure Attitudes and Leisure benefits of the Theme Paradise Tourists. J. Leis. Recreat. Ind. Manag. 2012, 5, 22–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Shih, H.M.; Lin, Y.S.; Liu, K.Y.; Chen, J.H. A Study on Tour Attraction, Perceived Value and Behavioral Intention on Coastal Sports for Tourists in Olympic Heng-Chun Open Water Swimming. J. Leis. Tour. Sport Health 2011, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.C.; Chang, L.H.; Chien, T.W. An Exploration of the Development of Marine Sports Industry based on Perspectives of Visitor Experience Quality, Perceived Values, and Revisiting Intentions. J. Manag. Pract. Princ. 2012, 6, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | No. | % | Variable | Category | No. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | male | 266 | 72.1% | Personal monthly income | Without income | 96 | 26% |

| female | 103 | 27.9% | below 20,000 NTD | 50 | 13.6% | ||

| Age | 15~18 | 30 | 8.1% | 20,001~35,000 NTD | 73 | 19.8% | |

| 19~22 | 72 | 19.5% | 35,001~50,000 NTD | 56 | 15.2% | ||

| 23~30 | 88 | 23.8% | 50,001~70,000 NTD | 43 | 11.7% | ||

| 31~40 | 90 | 24.4% | above 70,001 NTD | 51 | 13.8% | ||

| 41~50 | 55 | 14.9% | Karate participation years | occasional participation | 27 | 7.3% | |

| 51~60 | 21 | 5.7% | within 1 year | 22 | 6% | ||

| above 61 | 13 | 3.5% | 1~3 years | 64 | 17.3% | ||

| Marital status | single | 221 | 59.9% | 4~10 years | 108 | 29.3% | |

| married without child | 20 | 5.4% | 11~20 years | 71 | 19.2% | ||

| married with child | 110 | 29.8% | 21~30 years | 39 | 10.6% | ||

| others | 18 | 4.9% | over 31 years | 38 | 10.3% | ||

| Educational attainment | under junior high schools | 9 | 2.4% | Karate rank | grade 1~3 (brown belt) | 45 | 12.2% |

| senior high schools | 68 | 18.4% | grade 4~9 (red, purple, blue, green, yellow, orange belt respectively) | 35 | 9.5% | ||

| colleges or universities | 214 | 58% | beginning degree (black belt) | 96 | 26% | ||

| higher than graduate schools | 78 | 21.1% | degree 2~3 (black belt) | 125 | 33.9% | ||

| Occupation | students | 116 | 31.4% | degree 4~5 (black belt) | 51 | 13.8% | |

| government employees | 39 | 10.6% | above degree 6 (black belt) | 17 | 4.6% | ||

| service industry | 48 | 13% | Average times of weekly exercise participation in past three months | less than 1 time | 106 | 28.7% | |

| manufacturing industry | 29 | 7.9% | 1~2 times | 108 | 29.3% | ||

| commercial industry | 31 | 8.4% | 3~4 times | 81 | 22% | ||

| housekeepers | 7 | 1.9% | 5~7 times | 25 | 6.8% | ||

| self-employed | 29 | 7.9% | more than 7 times | 49 | 13.3% | ||

| others | 70 | 19% | Other martial art sports participation seniority | without participating | 155 | 42% | |

| Place of residence | north | 155 | 42% | occasional participation | 94 | 25.5% | |

| central | 136 | 36.9% | within 1 year | 27 | 7.3% | ||

| south | 57 | 15.4% | 1~3 years | 36 | 9.8% | ||

| east | 8 | 2.2% | 4~10 years | 31 | 8.4% | ||

| outlying islands | 13 | 3.5% | 11~20 years | 15 | 4.1% | ||

| 21~30 years | 8 | 2.2% | |||||

| more than 31 years | 3 | 0.8% |

| Variable | Dimension | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | Attraction | 4.497 | 0.556 |

| Lifestyle centrality | 3.642 | 0.817 | |

| Self-performance | 3.889 | 0.778 | |

| Overall involvement | 4.010 | 0.622 | |

| Perceived value | Money | 4.146 | 0.794 |

| Time | 4.371 | 0.684 | |

| Spirit and energy | 4.507 | 0.613 | |

| Overall perceived value | 4.341 | 0.605 | |

| Leisure benefits | Physiological benefits | 4.498 | 0.517 |

| Psychological benefits | 4.468 | 0.591 | |

| Social benefits | 3.887 | 0.742 | |

| Overall leisure benefits | 4.284 | 0.521 | |

| Recommendation intention | Informing advantages | 4.201 | 0.775 |

| Recommending to relatives, friends, and colleagues | 4.098 | 0.848 | |

| Suggesting participation | 4.276 | 0.830 | |

| Sharing knowledge | 4.431 | 0.727 | |

| Overall recommendation intention | 4.251 | 0.682 |

| Dimension | No. of Questions | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

| Involvement scale | 15 | 0.917 |

| Perceived value scale | 3 | 0.828 |

| Leisure benefits scale | 12 | 0.904 |

| Recommendation intention scale | 4 | 0.878 |

| Total scale | 34 | 0.953 |

| Variables | Involvement | Perceived Value | Leisure Benefits | Recommendation Intention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Involvement | 1 | |||

| Perceived value | 0.345 * | 1 | ||

| Leisure benefits | 0.267 ** | 0.338 * | 1 | |

| Recommendation intention | 0.587 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.621** | 1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | VIF | R2 | Adj. R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation intention | Attraction | 0.330 *** | 1.919 | 0.357 | 0.352 | 67.510 *** |

| Lifestyle centrality | 0.247 *** | 2.137 | ||||

| Self-performance | 0.100 * | 1.782 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | R2 | Adj. R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation intention | Perceived value | 0.619 *** | 0.302 | 0.300 | 158.668 *** |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | β | VIF | R2 | Adj. R2 | F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendation intention | Physiological benefits | 0.053 | 1.979 | 0.400 | 0.395 | 81.173 *** |

| Psychological benefits | 0.401 *** | 2.259 | ||||

| Social benefits | 0.311 *** | 1.478 |

| Research Hypothesis | Test Results |

|---|---|

| H1: Karate participants’ involvement positive affects the recommendation intention | Supported |

| H2: Karate participants’ perceived value positive affects the recommendation intention | Supported |

| H3: Karate participants’ leisure benefits positive affects the recommendation intention | Partially supported |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Y.-C.; Yeh, T.-M.; Pai, F.-Y.; Huang, T.-P. Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050953

Chang Y-C, Yeh T-M, Pai F-Y, Huang T-P. Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(5):953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050953

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ying-Chih, Tsu-Ming Yeh, Fan-Yun Pai, and Tai-Peng Huang. 2018. "Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 5: 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050953

APA StyleChang, Y.-C., Yeh, T.-M., Pai, F.-Y., & Huang, T.-P. (2018). Sport Activity for Health!! The Effects of Karate Participants’ Involvement, Perceived Value, and Leisure Benefits on Recommendation Intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 953. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15050953