Abstract

Objective: To describe patient satisfaction with pre-hospital emergency knowledge and determine if patients and professionals share a common vision on the satisfaction predictors. Methods: A qualitative study was conducted in two phases. First, a systematic review following the PRISMA protocol was carried out searching publications between January 2000 and July 2016 in Medline, Scopus, and Cochrane. Second, three focus groups involving professionals (advisers and healthcare providers) and a total of 79 semi-structured interviews involving patients were conducted to obtain information about what dimensions of care were a priority for patients. Results: Thirty-three relevant studies were identified, with a majority conducted in Europe using questionnaires. They pointed out a very high level of satisfaction of callers and patients. Delay with the assistance and the ability for resolution of the case are the elements that overlap in fostering satisfaction. The published studies reviewed with satisfaction neither the overall care process nor related the measurement of the real time in responding to an emergency. The patients and professionals concurred in their assessments about the most relevant elements for patient satisfaction, although safety was not a predictive factor for patients. Response capacity and perceived capacity for resolving the situation were crucial factors for satisfaction. Conclusions: Published studies have assessed similar dimensions of satisfaction and have shown high patient satisfaction. Expanded services resolving a wide number of issues that can concern citizens are also positively assessed. Delays and resolution capacity are crucial for satisfaction. Furthermore, despite the fact that few explanations may be given due to a lack of face-to-face attention, finding the patient’s location, taking into account the caller’s emotional needs, and maintaining phone contact until the emergency services arrive are high predictors of satisfaction.

1. Introduction

In the 1950s, Koos [1] proposed that patients be listened to in terms of what they had to say about the healthcare they received. Shortly thereafter, Donabedian [2] laid the foundations for the current conception of quality in the healthcare sector by definitively incorporating the patient’s perspective as a measure for the healthcare outcome. Then, some years later, Doll [3] asserted that healthcare must be evaluated by considering clinical effectiveness, efficiency, and acceptance by the patient for the care provided.

The concept of satisfaction has been related to attitudinal aspects, wherein the components had a distinct value depending upon the patient’s personal situation, and it was conceptualized as the result of the difference between how the patient had been attended to and his expectations about what such care should have been like [4]. Until well into the 20th century, the instruments for evaluating patient satisfaction had developed in an environment wherein the health system was centered on the professionals and not the patients. The changes promoting patient-centered care have led to the search for alternative methodologies.

Starting in the 1970s, patient satisfaction measures spread throughout the health services [4,5], commonly including evaluation of the following dimensions [6,7]: accessibility, professional competency, aspects of comfort and the physical appearance of facilities, availability of equipment, empathy of the professionals, information (quantity and quality) provided by the professionals, possibilities for choice, response capabilities of the professionals, and continuity of care between distinct care levels. Practically all research has focused on patient satisfaction following their discharge from the hospital or primary care.

The number of studies published regarding the satisfaction of patients who have accessed pre-hospital emergency services is limited considering the large numbers of patients who annually utilize this service (7,147,754 healthcare demands in 2015 in Spain [8]). Although some similarities might occur, there are expected differences in cases of an emergency. Moreover, in recent years, some countries that use an emergency telephone number have introduced new benefits such as completing administrative procedures, providing health advice over the phone that leads to a solution, instructing the user to go to a health center, and dispatching mobile units or health professionals to the location whether it is a public place or the caller’s home. In these cases, patients also speak to a highly trained adviser, supported by healthcare professionals, and the motive for calling is different from an emergency.

The aim of this study was to describe the knowledge about patient satisfaction with pre-hospital emergencies (telephone support, care provided, and emergency healthcare transport) and determine if patients and professionals share a common vision on the key variables for satisfaction.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative study conducted in two phases. First, a systematic review of the literature was carried out to identify methods applied to assess patient satisfaction with pre-hospital emergencies via the use of emergency telephone numbers (e.g., 911 in the USA and 112 in Europe) to request medical assistance or information from pre-hospital emergency services and search for improvement opportunities from their results. Second, three focus groups and a total of 79 semi-structured interviews were conducted to obtain information about what dimensions of care were a priority for patients and professionals (pre-hospital providers: physicians, nurses, and dispatchers). Dispatchers were trained to offer support over the telephone during an emergency. They use algorithms to make decisions and provide information or instructions. In this study, a pre-hospital emergency was defined as a demand for providing care for out-of-hospital health urgencies and emergencies. This includes telephone support, care provided in situ, and emergency healthcare transport. Pre-hospital emergencies are demanded by callers. Such callers are patients who dial the emergency telephone number (112 or 061) while in some cases, these calls are placed by others (relatives, friends, or anybody else) who help the patient by calling, asking for support.

2.1. First Phase: Literature Review

The PRISMA protocol was followed to analyze published research, both in English and Spanish, on satisfaction of the patient (of any age) with emergency telephone assistance, requests for emergency assistance, and emergency transport to a hospital. Publications (both quantitative and qualitative research) indexed between January 2000 and July 2016 in Medline, Scopus, and Cochrane were reviewed by combining the following MeSH terms: emergency telephone number, emergency telephone call center, out-of-hospital emergency telephone, pre-hospital emergency telephone, caller satisfaction emergency, medical services, out-of-hospital emergency, pre-hospital emergency, and ambulance, which were combined with the Boolean operator along with caller satisfaction and patient satisfaction.

The following inclusion criteria were established: research on any type of population, from elderly patients to parents of pediatric patients. Differences were not made based on the reasons for the call, pathology being dealt with, or who was making the call (the caller). All types of calls were included, no matter whether they were local, national, or international.

Excluded research included studies dealing with hospital emergencies, those that only described or evaluated the clinical attention during some part of the process (from the moment the call was placed until care was begun by the mobile unit, for example) without assessing the satisfaction of the attended user, those that described coordination mechanisms between units, those that assessed the satisfaction of professionals, and those that analyzed the quality of the decisions that healthcare professionals had to make (redirect the call or not, send a vehicle or something else, perform the intervention within the transport, or refer to the hospital).

The studies were reviewed independently by two of the authors to decide whether they fulfilled the inclusion criteria using the titles, abstracts, or full article. The final decision was made jointly by both of them. Additional articles were retrieved from the reference lists of the articles found by the initial online search. From the articles selected, the following information was categorized: year, country, objective, method or measurement, sample, evaluated dimensions of perceived quality, and outcomes.

2.2. Second Phase: Qualitative Research

This study, based on a qualitative research approach (using focus groups and semi-structured interviews), evaluated and compared the perspective of professionals with that of patients about what elements of perceived quality are most relevant for users of the services of the Sistema d’Emergències Mèdiques (Emergency Medical System, named SEM in Spanish) of Catalonia.

The Emergency Medical System is a public entity, dependent upon the Servei Català de la Salut (Catalonian Health Service), and is responsible for attending to, managing, and responding to demands for providing care for out-of-hospital health urgencies and emergencies in Catalonia. It serves 7 million people in an area of 32,000 km2. Its main access is via the telephone, with patients dialing 112 for emergencies and 061 for other health demands. The operational structure for the provision of this service includes a coordination center, 406 mobile units (326 basic life support and 80 advanced life support ambulances), and 4 medical helicopters.

Its coordination center is charged with taking and managing telephone calls. In 2016, it dealt with 1,473,609 cases, which was a 6% increase over 2015. Of these cases, 40.4% (595,156) were resolved without activating care resources, achieved by the consulting efforts and information provided by the professionals there. In patient care by pre-hospital emergency systems, two areas can be clearly differentiated: distance care and on site care. Distance care is provided by the professionals at the call reception center. The range of activities carried out at this level varies depending upon the central model. In the specific case of the SEM, these would be the following: taking the call, locating the patient, and triaging the situation with a computerized protocol. These functions are taken care of by the dispatchers, and based on the outcome of the initial triage, the call may be transferred to a second level of telephone dispatcher when the caller needs administrative information of a certain complexity; the call may also be transferred to health professionals, physicians, or nurses. This latter group asks about the patient’s medical history over the phone in accordance with some clinical procedures to better define the patient’s needs. The call may then finalize with the provision of health advice, or care in situ may be deemed necessary, resulting in the mobilization of a resource (ambulance or medical helicopter). When mobilizing a resource is deemed necessary, the coordination center decides upon the most suitable type depending upon the isochrone map and the patient’s pathology, it coordinates the activated resources, and when necessary, the transport to the health center, deciding which is most suitable depending upon its distance and saturation level, information that the coordination center has available at all times. On site care is that provided by the professionals from the teams of the care resources, ambulances, and helicopters. Once they reach the patient, care consists in learning the patient’s medical history, exploration, treatment and, if necessary, transport to a health center with care provided during the ambulance ride.

Telephone calls by citizens are handled by two types of professionals: first there are demand managers (dispatchers), and then there are pre-emergency providers, and these include physicians and nurses. Dispatchers are responsible for taking calls, and after a short consultation with the caller and interaction using a computerized protocol, a response may be generated or the call may be referred to a second level of attention. These professionals have experience and have been trained on providing care for patients via telephone support platforms, and prior to working professionally at the SEM, they receive specific training on the tools to use, certain skills for telephone assistance in urgencies and emergencies, operational SEM protocols, and also on basic health knowledge. They also undergo continuous training. In the latter case, and provided the demand is for informative content, the call is attended to by a group of dispatchers who are not health professionals but nonetheless can spend greater time responding to the citizen in an appropriate manner. These types of calls make up the group of administrative consultations. Issues related to the services provided by the Catalonian Health Service are the main reason for telephone consultations, and in 2016, there were 211,702 such administrative consultations. In the event that a call referred to the second level corresponds to a consultation on a health urgency, the call is transferred to either a physician or a nurse (depending upon the content of the consultation). In 2016, there were 324,821 of these health consultations.

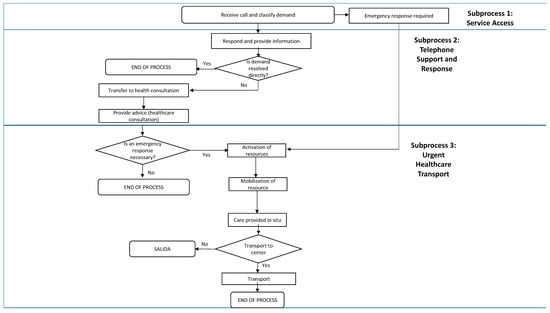

Figure 1 details the analyzed SEM-061 care process that was assessed, divided into three subprocesses. Subprocess 1: Service Access (accessibility to the care line). Subprocess 2: Telephone Support and Response (call answered and classified, assessment of the assistance provided over the phone). Subprocess 3: Emergency Healthcare Transport (mobilization of care resource, arrival of care resource and care provided in situ, decision about transport, care provided during transport, and lastly, the transition to the health center). This study explored the different subprocesses that began when the patient (or somebody else) dialed 112 or 061 and until they either received care at the location they were found in or were transported to a healthcare center, and finally whether the patient was transferred to the hospital, and until the emergency care process was considered finished.

Figure 1.

SEM-061 care process.

2.3. Perception of Professionals

Three focus groups were led by 23 professionals (14 pre-hospital providers from the coordination centers of Reus and Hospitalet (pre-hospital emergency 061 CatSalut Respon) and 9 professionals who provided care at the second level, urgent health transport). Sixteen semi-structured interviews (see Supplementary Table S1) were conducted with telephone dispatchers from the pre-hospital emergency 061 CatSalut Respon service. Participation was voluntary after the study objectives and methodology were explained to them. The selection of these professionals considered their professional experience (less than 6 months, 1–3 years, or more than 3 years) on different shifts (morning, afternoon, evening, weekend), and there was equal representation from areas (urban and rural) in addition to balance between men and women.

2.4. Perception of Patients

To select users who called SEM, a random sample of 264 callers who had used both the 112 and 061 services was identified from the CatSalut billing database. Of these users, 119 (45%) called for administrative or health consultations, and the remaining 145 (55%) requested urgent medical transport and were conscious when the care arrived in order to be able to report on the care they had received. Prior to conducting the semi-structured interview, each caller was asked whether they retained sufficient memory to assess different aspects of the quality of the service they had received. As such, 34 (13%) said that they did not retain sufficient memory of the events to report on the care that they had received, 41 (16%) were very active users of both emergency and non-emergency transport services but unable to assess the quality of both services differently, and 66 (25%) declined to participate in the interview.

Ultimately, 63 callers (24%) participated in semi-structured interviews lasting 10–15 min; 33 of them had called for administrative consultations whereas the remaining 30 had dialed 061 for healthcare requests (see Supplementary Table S2). Additionally, and in the case of emergency medical transport, a subsample of 55 callers (22%) for emergency medical transport from different areas of Catalonia were interviewed in depth to attain an approximation of the user population for this service.

The inclusion criteria included the following: be between 18 and 90 years of age and a caller of 061 in the preceding 6 months (September 2016–February 2017) for either an administrative or a health consultation. Those requesting emergency medical transport had to have called during the preceding year (2016) for the following possible varieties: advanced vital support (SVA), basic vital support (SVB), medical helicopter, rapid intervention vehicle (VIR), or the unit of continuous home care. Likewise, geographic origin was taken into account for callers of administrative and health consultations alike, as well as for callers requesting urgent health transport, since the territorial variable was a variable that could affect perception; thus, an attempt was made to distribute the sample in rural and urban areas.

3. Results

3.1. First Phase: Literature Review

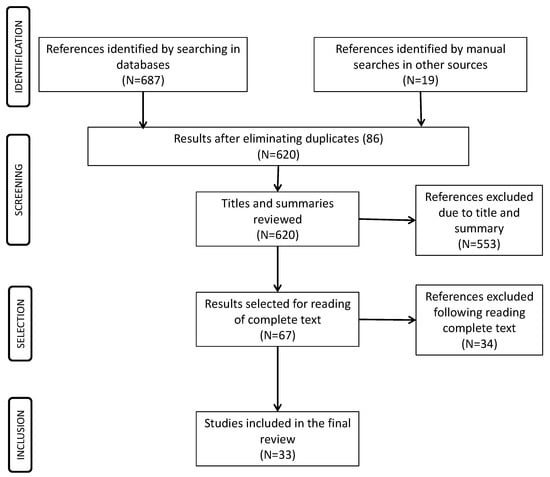

The search strategy produced 620 additional studies that were of potential interest for this study, and after reviewing their titles and abstracts, this figure was reduced to 67 (Figure 2). After completely reading those 67 texts, 33 relevant studies were identified (Table 1).

Figure 2.

PRISMA figure. Results of the literature review.

Table 1.

Description of studies included in final review.

Most of the studies published on satisfaction with the telephone assistance provided by pre-hospital emergency services are of the descriptive variety (71%) that employed either surveys, questionnaires, or structured interviews with patients. Most of these were carried out in the United Kingdom (41%). Of the reviewed studies, 24% of them were systematic reviews of the literature, although not always using the PRISMA methodology. None of the published studies reviewed the overall care process; instead, they focused on parts of the process such as telephone triage, communications skills of the attending professionals, if the recommendations were ultimately carried out, and whether there was any follow-up.

The most frequent origin for published studies on emergency healthcare assistance that included transport, normally via ambulance (none inquired about other transport means, such as helicopter, water craft, etc.), was once again the United Kingdom (36%). The majority of these were descriptive studies (75%) that coincide in pointing out a very high level of satisfaction of callers and patients, although the fact of being attended to by various telephone dispatchers, technicians, or healthcare professionals during the same phone call is indicated in these as practically the lone cause for dissatisfaction. Delay with the assistance and the ability for resolution of the case are the elements that overlap in fostering satisfaction. No studies relate the measurement of the real time in responding to an emergency with the satisfaction of patients.

The care elements that are recognized as generating confidence and professionalism include short wait times, receiving information on the reasons for the transport, the patient’s expectations coinciding with the action taken by the professional (for example, being transported or not), and attending to both the physical as well as emotional aspects of the assistance. Studies that address the problems of language difficulties have not been found, for example, assistance for foreigners in tourist areas or cultural differences due to religion that require differentiated treatment, such as male/female relationships.

Entirely all the studies on satisfaction with emergency services show that in all countries, continents, and systems, such as Malaysia, Japan, USA, Europe, and Australia, patients report feeling very satisfied with the dimensions evaluated in the instruments employed (treatment perceived as adequate, information, delay, conditions of transport, capacity for resolution) [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, these approaches have not provided information for identifying improvement opportunities, for example on patient safety. Sharing the vision of professionals and patients could probably be a good complement to identify opportunities for care process improvement. Analyzing the care elements that influence more directly on this satisfaction and exploring alternative methodological approaches to opinion surveys could provide qualitatively different information for learning about the experiences of patients who require these services. Published studies have focused on patients using ambulances, but no patients were included who required air or maritime transport.

3.2. Second Phase: Qualitative Research

The patients (callers) and professionals (dispatchers and pre-hospital providers) concurred in their assessments about the most relevant elements for the patient when patients use the emergency telephone and also in the assessments they both made about said service (Table 2 and Table 3). Likewise, they also agreed on the quality criteria for patients when mobilizing a unit such as an ambulance or helicopter is required (Table 4).

Table 2.

Subprocess 1: Service Access.

Table 3.

Subprocess 2. Telephone Support and Response.

Table 4.

Subprocess 3: Urgent Healthcare Transport.

3.2.1. Accessibility

Patients generally know what telephone number to call in emergencies or when they need health information, and they use this telephone service correctly. In the same manner, both groups (patients and professionals) agreed that the new communication channels (chat, email, apps) were not sufficiently known about or utilized, even for patients who usually accessed, due to their domestic situation, the emergency telephone number. However, the time required to resolve the call were higher when patients used 112 because this is a general entrance for all type of emergencies including health emergencies. Patients calling 112 usually needed to repeat the same information to a second professional.

3.2.2. Response Capacity

Both groups pointed out the delay by which telephone assistance is carried out as a critical criterion of quality, and the patients stated this was adequate. The professionals, for their part, properly sensed that the delay in providing care was key, and that the assessment by patients in this regard was positive. The main gap of having to repeat practically the very same information again and again when the phone call is transferred to different professionals during the same call was identified by both groups; one example of this is when the call is transferred after the patient has activated her medical alert button and already talked first to the providers of that service. Furthermore, in these cases, there could be sporadic delays or even waits before the physician or nurse returns the call a few minutes later (adjusted according to urgency).

The professionals emphasized that if the caller was not the patient, obtaining reliable information was more complicated, and this aspect was also recognized by patients during the interviews.

As for mobilizing resources (ambulance, helicopter, etc.), the impression conveyed by patients is that a delay in receiving assistance is the factor they valued most when judging the efforts by the emergency service and that, in all cases, the resource arrived quickly. The professionals agreed on that assessment, although they pointed out difficulties when the caller did not know about his location, or the problems of finding him in certain rural locations, especially mountainous terrain. Moreover, one variable that professionals pointed out that leads to delays in attending to the emergency call is when the caller is a tourist and does know exactly where he is; this makes pinpointing his exact location difficult.

3.2.3. Professionalism

Another relevant aspect for patients is the professionalism in how the situation is handled, both when gathering information from the patient as well as when offering structured information in a logical and comprehensible manner. Patients assessed both of these aspects positively. Furthermore, the professionals correctly sensed the assessments that patients made. In general, the comments by patients who were interviewed indicate that they felt that they were correctly understood, including emotional aspects that accompany uncertainties during emergencies.

Although patients did not indicate to be a problem the fact that telephone operators did not remain on the line with them once the emergency assistance request was made until the resource arrived at their location, the professionals did agree in pointing out that in this care, also attending to the emotional needs of patients entails a higher level of quality. Patients and professionals alike agreed in their assessments that the resources mobilized brought the appropriate means and professionals for dealing with the emergency care request and that, therefore, a suitable use of the means available was made. Patients and their companions (when applicable) received correct information about the patient’s situation, the treatment being administered, and where they were being taken.

3.2.4. Transport Conditions

Patients did not pay special attention to the safety conditions during the emergency transport whereas professionals did value them and considered them important. However, the patients’ opinions about these conditions were that the transport was carried out correctly and safely. Callers of pediatric patients described how the transport went about for these minors (a child of theirs) in a manner that was consistent with the care protocol that the professionals described during the interviews for this young population. When the parents were aware of this protocol during the interview, they assessed it positively.

3.2.5. Capacity for Resolving the Situation

Both groups agreed on this aspect as crucial for determining the quality of the care and in the positive assessments made by patients in this regard. There were many emergencies that were resolved in the same place as the incident (home, hotel, beach, street). Thus, the capacity for resolving emergencies was not only related to safety and fast transportation to a hospital.

The patients stated that the transport took place quickly and without incident, their personal belongings were not lost, and that in the transition to the emergency hospital personnel attending to them, teams there took charge of their care in the terms in which they had been informed. The professionals pointed out this transition as a critical point for patient safety and that the information between professionals and the patient should improve. The professionals also pointed out that a protocol should be applied to ensure that personal belongings are returned to patients.

4. Discussion

Treatment perceived as adequate, information about diagnosis, treatment and hospital to be transferred to, delays, conditions of transport, and capacity for resolution are the dimensions of patient satisfaction usually explored in the literature. More than 85% of patients are usually satisfied with pre-hospital emergency services, whereas repeating the same information when being served by several operators is a cause for dissatisfaction.

The dimensions of satisfaction identified in this study coincide with those indicated in the literature as keys to the satisfaction of these patients. The results of this study have yielded new aspects to be considered, such as professionalism also including that the telephone operator is capable of finding the location from which the call requesting assistance is placed when the caller himself does not know where he is, and that the professionals also attend to the emotional needs of the person making the call.

Patients, dispatchers, and healthcare providers share the crucial assistance and care quality perceived dimensions. The professionals correctly identify what patients consider crucial when receiving information or care and their level of satisfaction. These results also coincide that satisfaction with these services is very high. The expectancies of patients about emergencies are related to delays and resolution capacity while professionals considered other aspects related with safety, a dimension not considered by patients.

Emergency services have expanded their services and offer agile and reliable information on a wide number of issues that can concern citizens and, for that matter, patients, such as resolving doubts about the correct use of a medication, information about how to correctly interpret a medical indication, knowing where to go when in search of health assistance, and requesting emergency assistance at home. This change has been shown to be useful and that it achieves a positive impact on the user population [27]. The results of this study confirm these initial assessments, although they indicate that when defining the emergency care processes, they should consider that the organization should prevent the caller from repeating the same information to various telephone operators.

From a methodological point of view, these results show that while the memory of the ambulance ride (if the clinical conditions so allow) remains over time, the same does not happen with memory when dialing 061 to obtain timely information, even during stressful moments. The reality is that, as was shown previously [9], users of this service learn quickly to raise doubts over the phone, and their assessments when asked are overall ones because most of them do not remember the last time that they called. Also, when these services are assessed, the diversity and complexity of the health service being offered must be kept in mind. For example, it is necessary to take into account that when conducting evaluations of these health services, a large number of emergencies are resolved in the location where they take place and do not require transport in an ambulance or any other mode of transportation.

The result of studies on patient satisfaction have highlighted some of the predictors of satisfaction such as [42,43,44,45] age, intimacy, and cleanliness, length of hospital stays, knowing what type of professional they were dealing with at any moment, information at admission and about home care after discharge, patient-reported experiences with the nursing and physician services, perceived the treatment as correct, and fulfillment of patient expectations. In the case of the emergency services, this study revealed as variables important to satisfaction that the caller perceives that their necessities are understood by the telephone operator and that telephone contact is maintained during the time they wait for the ambulance to arrive.

There is a concentration of studies in Europe. The generalization of results to other countries might be limited as this uses a qualitative research approach. There was no random selection of professionals involved in focus groups. The assessments were not related with objective measures of assistance such as length of phone assistance, delays, claims or adverse events.

As far as we have been able to determine, this is the first study that examines the entire care process that is carried out by emergency service providers, and it is designed to learn about what care aspects are relevant for patients and whether the professionals keep these dimensions in mind. Its qualitative methodology allows an alternative approach to that of survey-based studies and, as seen in this case, provides information for introducing improvements in the care process.

5. Conclusions

Worldwide, there is high satisfaction with pre-emergency hospital services. The expanded services offering agile and reliable information on a wide number of issues that can concern citizens also yield high satisfaction. Pre-emergency patients, dispatchers, and healthcare providers share the crucial assistance and care quality perceived dimensions.

The dimensions of satisfaction usually assessed include delays and resolution capacity that are crucial for fulfilling patients’ and callers’ expectation about this service. Finding the location from which the call requesting assistance is placed, maintaining contact with the patient until the emergency services arrive, and attending to the emotional needs of the person making the call are high predictors of satisfaction. These are key elements when callers (and patients) assess the professionalism of the dispatchers and the healthcare providers. Repeating the same information when being served by several operators is the principal cause for dissatisfaction.

When satisfaction is assessed, the role of callers and patients must be considered because many times the callers cannot provide reliable information.

This study describes some methodological issues to be considered when satisfaction instruments are developed and the gaps and strengths of the pre-emergency care that could contribute to improve the satisfaction of callers (and patients).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/2/233/s1, Table S1: Survey Instrument. Caller/User, Table S2: Survey Instrument. Professionals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and the professionals for their generosity participating in this study.

Author Contributions

Jose Joaquín Mira, Anna Puig and Fernando García-Alfranca conceived and designed the study. Virtudes Pérez-Jover and Mercedes Guilabert review the literature. Ismael Cerdá and Hortensia Aguado acquired the data for the work. Irene Carrillo prepared the data and together with Mercedes Guilabert and Virtudes Pérez-Jover conducted qualitative analysis. All interpreted data for the work. Carles Galup and Ismael Cerdá prepared a first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the paper critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koos, E. The Health of Regionsville; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian, A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966, 44, 166–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, R. Surveillance and monitoring. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1974, 3, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder-Pelz, S. Social psychological determinants of patient satisfaction: A test of five hypotheses. Soc. Sci. Med. 1982, 16, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzia, J. How valid and reliable are patient satisfaction data? An analysis of 195 studies. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 1999, 11, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J. La satisfacción del paciente: Teorías, medidas y resultados. Todo Hosp. 2006, 224, 90–97. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.; Dornan, M. What patients like about their medical care and how often they are asked: A meta-analysis of the satisfaction literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 27, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicios de Urgencias y Emergencias 112/061. Datos 2015. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/estadisticas/estMinisterio/SIAP/Estadisticas.htm (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Hadsund, J.; Riiskjær, E.; Riddervold, I.S.; Christensen, E.F. Positive patients’ attitudes to pre-hospital care. Dan. Med. J. 2013, 60, A4694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swain, A.H.; Al-Salami, M.; Hoyle, S.R.; Larsen, P.D. Patient satisfaction and outcome using emergency care practitioners in New Zealand. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2012, 24, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisah, A.; Chew, K.S.; Mohd Shaharuddin Shah, C.H.; Nik Hisamuddin, N.A. Patients’ perception of the ambulance services at Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia. Singap. Med. J. 2008, 49, 631–635. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, S.; Knowles, E.; Colwell, B.; Dixon, S.; Wardrope, J.; Gorringe, R.; Snooks, H.; Perrin, J.; Nicholl, J. Effectiveness of paramedic practitioners in attending 999 calls from elderly people in the community: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2007, 335, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, A.W.; Lindsell, C.J.; Handel, D.A.; Collett, L.; Gallo, P.; Kaiser, K.D.; Locasto, D. Postal survey methodology to assess patient satisfaction in a suburban emergency medical services system: An observational study. BMC Emerg. Med. 2007, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Meara, P. Ambulance satisfaction surveys: Their utility in policy development, system change and professional practice. JEPHC 2003, 1, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Persee, D.E.; Key, C.B.; Baldwin, J.B. The effect of a quality improvement feedback loop on paramedic-initiated nontransport of elderly patients. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2002, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar]

- Neumayr, A.; Gnirke, A.; Schaeuble, J.C.; Ganter, M.T.; Sparr, H.; Zoll, A.; Schinnerl, A.; Nuebling, M.; Heidegger, T.; Baubin, M. Patient satisfaction in out-of-hospital emergency care: A multicenter survey. Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 23, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.; Coster, J.; Chambers, D.; Cantrell, A.; Phung, V.-H.; Knowles, E.; Bradbury, D.; Goyder, E. What Evidence Is There on the Effectiveness of Different Models of Delivering Urgent care? A Rapid Review; School for Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Booker, M.J.; Shaw, A.R.G.; Purdy, S. Why do patients with ‘primary care sensitive’ problems access ambulance services? A systematic mapping review of the literature. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamam, A.F.; Bagis, M.H.; AlJohani, K.; Tashkandi, A.H. Public awareness of the EMS system in Western Saudi Arabia: Identifying the weakest link. Int. J. Emerg. Med. 2015, 8, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togher, F.J.; O’Cathain, A.; Phung, V.H.; Turner, J.; Siriwardena, A.N. Reassurance as a key outcome valued by emergency ambulance service users: A qualitative interview study. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2951–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronsson, K.; Björkdahl, I.; Wireklint Sundström, B. Pre-hospital emergency care for patients with suspected hip fractures after falling—Older patients’ experiences. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 3115–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kietzmann, D.; Wiehn, S.; Kehl, D.; Knuth, D.; Schmidt, S. Migration background and overall satisfaction with pre-hospital emergency care. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2016, 29, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keene, T.; Davis, M.; Brook, C. Characteristics and outcomes of patients assessed by paramedics and not transported to hospital: A pilot study. Australas. J. Paramed. 2015, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Studnek, J.R.; Fernandez, A.R.; Vandeventer, S.; Davis, S.; Garvey, L. The association between patients’ perception of their overall quality of care and their perception of pain management in the pre-hospital setting. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2013, 17, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togher, F.J.; Davy, Z.; Siriwardena, A.N. Patients’ and ambulance service clinicians’ experiences of pre-hospital care for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: A qualitative study. Emerg. Med. J. 2013, 30, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, A.; Ekwall, A.; Wihlborg, J. Patient satisfaction with ambulance care services: Survey from two districts in Southern Sweden. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2011, 19, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Knowles, E.; Turner, J.; Nicholl, J. Acceptability of NHS 111 the telephone service for urgent health care: Cross sectional postal survey of users’ views. Fam. Pract. 2014, 31, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasqueiro, S.; Oliveira, M.; Encarnação, P. Evaluation of telephone triage and advice services: A systematic review on methods, metrics and results. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2011, 169, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ström, M.; Marklund, B.; Hildingh, C. Callers’ perceptions of receiving advice via a medical care help line. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2009, 23, 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, C.; Soriano, F.; Morant, F. Análisis de la calidad percibida por los usuarios externos de la Unidad de Coordinación de Transporte Sanitario no Asistido de Alicante. Rev. Calid. Asist. 2011, 26, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaulieu, R.; Humphreys, J. Evaluation of a telephone advice nurse in a nursing Managed pediatric community clinic. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2008, 22, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.; Avies-Jones, A. An audit of the NICE self-harm guidelines at a local accident and emergency department in North Wales. Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 15, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.; O’Keeffe, C.; Coleman, P.; Edlin, R.; Nicholl, J. Effectiveness of emergency care practitioners working within existing emergency service models of care. Emerg. Med. J. 2007, 24, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halter, M.; Marlow, T.; Tye, C.; Ellison, G.T. Patients’ experiences of care provided by emergency care practitioners and traditional ambulance practitioners: A survey from the London Ambulance Service. Emerg. Med. J. 2006, 23, 865–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, K.; Kihlgren, M.; Ostman, I.; Sørlie, V. Patients with acute chest pain—Experiences of emergency calls and pre-hospital care. J. Telemed. Telecare 2005, 11, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, S.; O’Keeffe, C.; Coleman, P.; Edlin, R.; Nicholl, J. A National Evaluation of the Clinical and Cost Effectiveness of Emergency Care Practitioners; 2005 Medical Care Research Unit (MCRU); University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Machen, I.; Dickinson, A.; Williams, J.; Widiatmoko, D.; Kendall, S. Nurses and paramedics in partnership: Perceptions of a new response to low-priority ambulance calls. Accid. Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 15, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snooks, H.; Kearsley, N.; Dale, J.; Halter, M.; Redhead, J.; Cheung, W.Y. Towards primary care for non-serious 999 callers: Results of a controlled study of “Treat and Refer” protocols for ambulance crews. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2004, 13, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cariello, F.P. Computerized Telephone Nurse Triage. An Evaluation of Service Quality and Cost. J. Ambul. Care Manag. 2003, 26, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cathain, A.; Turner, J.; Nicholl, J.P. The acceptability of an emergency medical dispatch system to people who call 999 to request an ambulance. Emerg. Med. J. 2002, 19, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Cathain, A.; Munro, J.F.; Nicholl, J.P.; Knowles, E. How helpful is NHS Direct? Postal survey of callers. BMJ 2000, 320, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quintana, J.M.; González, N.; Bilbao, A.; Aizpuru, F.; Escobar, A.; Esteban, C.; San-Sebastián, J.A.; de-la-Sierra, E.; Thompson, A. Predictors of patient satisfaction with hospital health care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006, 6, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, J.J.; Tomás, O.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Nebot, C.; Rodríguez-Marin, J. Predictors of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery 2009, 145, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petek, D.; Kersnik, J.; Szecsenyl, J.; Wensing, M. Patients’ evaluations of European general practice—Revisited after 11 years. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2011, 23, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjertnaes, O.A.; Strømseng Sjetne, I.; Iversen, H. Overall patient satisfaction with hospitals: Effects of patient-reported experiences and fulfilment of expectations. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2012, 21, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).