Physical Activity Programming Advertised on Websites of U.S. Islamic Centers: A Content Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

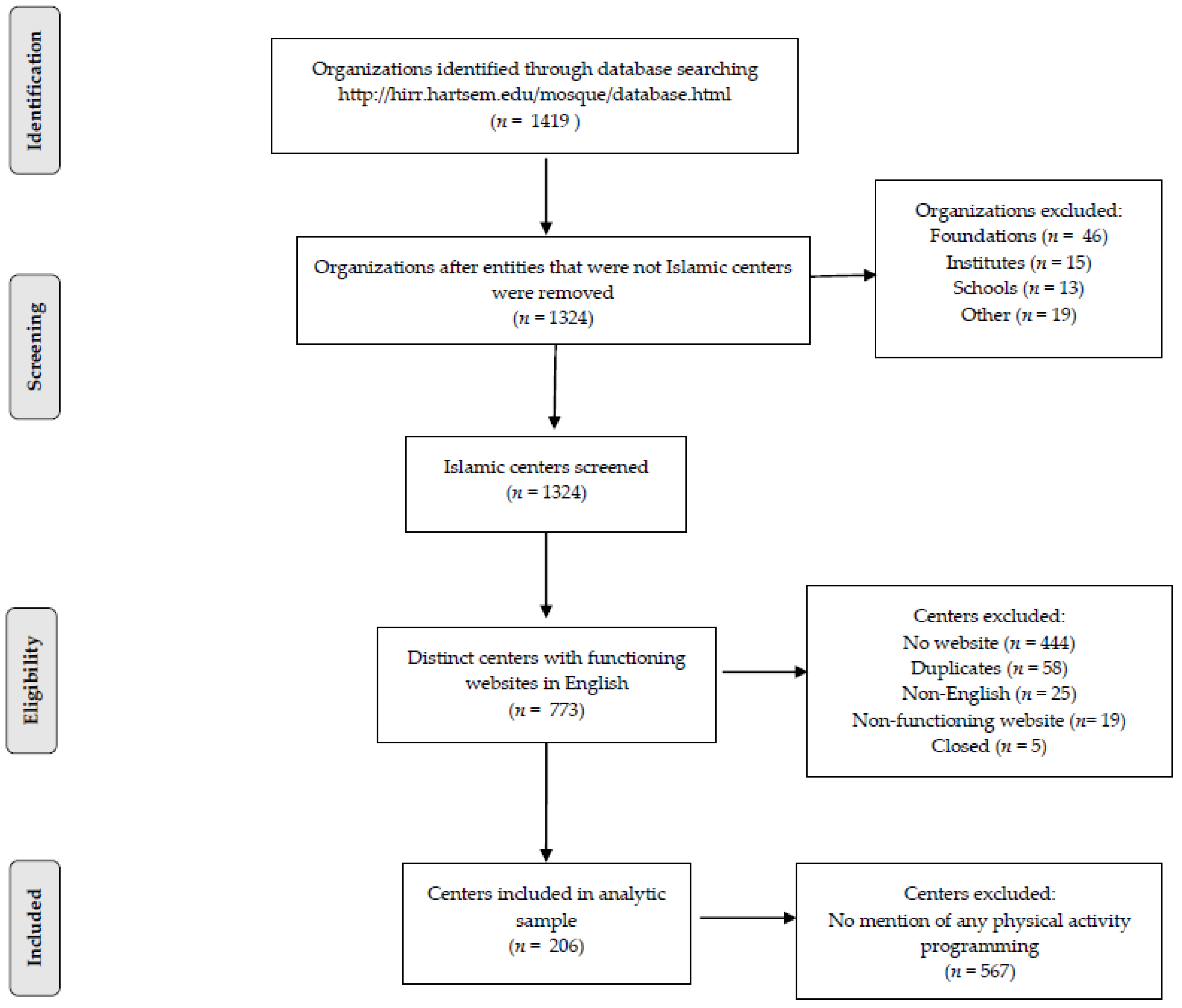

2.1. Sample Derivation

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Classification

- (1)

- Camps included summer, weekend, and specialty camps open to families, adults, or youth.

- (2)

- Fitness classes included regularly meeting martial arts, exercise or fitness, or non-sport, classes open to families, adults, or youth.

- (3)

- Sports programs included regularly meeting practices, games, and leagues for individual, dual, and team sports open to adults or youth.

- (4)

- Youth group programs included those found on youth group pages or distinguished as intended for youth.

- (5)

- Irregular programs included those that were offered once (i.e., special event), infrequently/irregularly, or intermittently and open to families, adults, or youth.

2.4. Variable Derivation

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Overview

3.2. Camps

3.3. Fitness Classes

3.4. Sports Programs

3.5. Youth Group Activities

3.6. Irregular Programs

4. Discussion

Specific Recommendations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Specific Physical Activities and Frequencies by Program Category for Activities with Frequency < 5.

| Category | Activities |

| Camp | Ropes (4); biking, football, horseback riding, physical activities and fitness, tennis (all 3); baseball, karate, tug of war (all 2); badminton, bowling, challenge course, gymnastics, human foosball, log rolling, open gym, outdoor play, paintball, relays, running, skateboarding, skating, table tennis, taekwondo, team building games, trampoline, water skiing, wrestling, Zumba (all 1) |

| Fitness | Kickboxing, self-defense (4 each); jiu jitsu, judo, mixed martial arts (3 each); aerobics, movement activities, sports, swimming, zumba (2 each); aikido, crossfit, tai chi (1 each) |

| Sport | Football (4); open gym, sports (3 each); baseball, tennis, wrestling (2 each); archery, bowling, fencing, golf, pickleball (1 each) |

| Youth | Football, volleyball (4 each); horseback riding, skiing (3 each); archery, ice skating, multievent, table tennis, swimming, whitewater rafting (2 each); biking, bocce, climbing, cricket, dance, karate, self-defense, skating, snow tubing, tennis, walking (1 each) |

| Irregular | Badminton, cricket (4 each); bounce house, hiking, self-defense, swimming, table tennis, tennis (3 each), biking, folkdance, Frisbee, horseback riding, obstacle course, skiing, volleyball, yoga (2 each); baseball, bowling, golf, horseshoes, ice skating, karate, laser tag, physical activities, tug of war, wrestling (1 each) |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44399/1/9789241599979_eng.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Physical Activity and Health. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pa-health/index.htm (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Sallis, J.F.; Bull, F.; Guthold, R.; Heath, G.W.; Inoue, S.; Kelly, P.; Oyeyemi, A.L.; Perez, L.G.; Richards, J.; Hallal, P.C. Progress in physical activity over the Olympic quadrennium. Lancet 2016, 388, 1325–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumith, S.C.; Hallal, P.C.; Reis, R.S.; Kohl, H., III. Worldwide prevalence of physical inactivity and its association with human development index in 76 countries. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, D. Adult physical inactivity prevalence in the Muslim world: Analysis of 38 countries. Prev. Med. Rep. 2015, 2, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuelezam, N.N.; El-Sayed, A.M.; Galea, S. The health of Arab Americans in the United States: An updated comprehensive literature review. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanaya, A.M.; Herrington, D.; Vittinghoff, E.; Ewing, S.K.; Liu, K.; Blaha, M.J.; Dave, S.S.; Qureshi, F.; Kandula, N.R. Understanding the high prevalence of diabetes in U.S. South Asians compared with four racial/ethnic groups: The MASALA and MESA studies. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1621–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieru, J.W.; Tan, E.M.; St. Sauver, J.; Jacobson, D.J.; Agunwamba, A.A.; Wilson, P.M.; Rutten, L.J.; Damodaran, S.; Wieland, M.J. High rates of diabetes mellitus, pre-diabetes and obesity among Somali immigrants and refugees in Minnesota: A retrospective chart review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2016, 18, 1343–1349. [Google Scholar]

- Budhwani, H.; Borgstede, S.; Palomares, A.L.; Johnson, R.B.; Hearld, K.R. Behavior and risks for cardiovascular disease among Muslim women in the United States. Health Equity 2018, 2, 264–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipka, M. Muslims and Islam: Key Findings in the U.S. and Around the World. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/08/09/muslims-and-islam-key-findings-in-the-u-s-and-around-the-world/ (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Wieland, M.L.; Weis, J.A.; Palmer, T.; Goodson, M.; Loth, S.; Omer, F.; Abbenyi, A.; Krucker, K.; Edens, K.; Sia, I.G. Physical activity and nutrition among immigrant and refugee women: A community-based participatory research approach. Womens Health Issues 2012, 22, e225–e232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.E.; Ermias, A.; Lung, A.; Mohamed, A.S.; Ellis, B.H.; Linke, S.; Kerr, J.; Bowen, D.J.; Marcus, B.H. Culturally adapting a physical activity intervention for Somali women: The need for theory and innovation to promote equity. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017, 7, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, E.; Ali, M.; Graham, E.; Quan, L. Responding to a request: Gender-exclusive swims in a Somali community. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieland, M.L.; Tiedje, K.; Meiers, S.J.; Mohamed, A.A.; Formea, C.M.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Asiedu, G.B.; Boyum, G.; Weis, J.A.; Nigon, J.A.; et al. Perspectives on physical activity among immigrants and refugees to a small urban community in Minnesota. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2015, 17, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, K.E.; Mohamed, A.S.; Dawson, D.B.; Syme, M.; Abdi, S.; Barnack-Taviaris, J. Somali perspectives on physical activity: Photovoice to address barriers and resources in San Diego. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.T.; Dhalac, D.; Suldan, A.A.; Jacobs, A.; Guled, K.; Bankole, K.A. Determinants of physical activity among Somali women living in Maine. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2012, 14, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothe, E.; Holt, C.; Kuhn, C.; McAteer, T.; Askari, I.; O’Meara, M.; Sharif, A.; Dexter, W. Barriers to outdoor physical activity in wintertime among Somali youth. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2010, 12, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinescu, L.G.; Sharify, D.; Krieger, J.; Saelens, B.E.; Calleja, J.; Aden, A. Be active together: Supporting physical activity in public housing communities through women-only programs. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2013, 7, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, D. Arab American college students’ physical activity and body composition: Reconciling Middle East-West differences using the socioecological model. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2011, 82, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamzeh, M.; Oliver, K.L. “Because I am Muslim, I cannot wear a swimsuit”: Muslim girls negotiate participation opportunities for physical activity. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2012, 83, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, L.; Mili, S.; Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Islam, N. Using qualitative methods to understand physical activity and weight management in New York City, 2013. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahan, D.; Amini, H.; Osman, M. Formative evaluation of a pilot study of a university exercise class for female Muslims. J. Phys. Act. Res. 2018, 3, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UC San Diego’s Center for Community Health [UCSD-CCH]. Improving Muslim Youth Participation in Physical Education and Physical Activity in San Diego County; UCSD-CCH: San Diego, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- National Physical Activity Plan Alliance (NPAPA). Faith-Based Settings. Available online: http://www.physicalactivityplan.org/theplan/faithbased.html (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Pew Research Center. U.S. Muslims Concerned About their Place in Society, but Continue to Believe in the American Dream. Findings from Pew Research Center’s 2017 Survey of U.S. Muslims; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, Y.; Baker, D.; Puligari, P.; Melody, T.; Yeung, J.; Gao-Smith, F. The role of imams and mosques in health promotion in Western societies—A systematic review protocol. Syst. Rev. 2017, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padela, A.; Killawi, A.; Heisler, M.; Demonner, S.; Fetters, M.D. The role of imams in American Muslim health: Perspectives of Muslim community leaders in southeast Michigan. J. Relig. Health 2011, 50, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padela, A.I.; Malik, S.; Ahmed, N. Acceptability of Friday sermons as a modality for health promotion and education. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, R.; Warsi, S.; Amos, A.; Shah, S.; Mir, G.; Sheikh, A.; Siddiqi, K. Involving mosques in health promotion programmes: A qualitative exploration of the MCLASS intervention on smoking in the home. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.T.; Landry, M.; Zawi, M.; Childerhose, D.; Stephens, N.; Shafique, A.; Price, J. A pilot examination of a mosque-based physical activity intervention for South Asian Muslim women in Ontario, Canada. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2017, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killawi, A.; Heisler, M.; Hamid, H.; Padela, A.I. Using CBPR for health research in American Muslim mosque communities. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2015, 9, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, N. American Muslims in the age of new media. In Oxford Handbook of American Islam; Haddad, Y.Y., Smith, J.I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 376–388. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvy, L.; Chatterjee, K. Muslim women’s use of Internet media in the process of acculturation in the United States. Qual. Res. Rep. Commun. 2017, 18, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orizio, G.; Rubinelli, S.; Nava, E.; Domenighini, S.; Caimi, L.; Gelatti, U. The Internet and health promotion: A content analysis of the official websites of Italian public health authorities. J. Med. Person 2010, 8, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagby, I. The American Mosque 2011. Report Number 1 from the US Mosque Study 2011. Basic Characteristics of the American Mosque—Attitudes of Mosque Leaders; Council on American-Islamic Relations: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hartford Institute for Religion Research. Database of Masjids, Mosques and Islamic Centers in the U.S. Available online: http://hirr.hartsem.edu/mosque/database.html (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Bagby, I. Mosques in the United States. In Oxford Handbook of American Islam; Haddad, Y.Y., Smith, J.I., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 225–236. [Google Scholar]

- Muslim Names. Available online: http://www.muslimnames.info/ (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Muslim Surnames: The Most Common Surnames of Muslim Origin in the USA. Available online: http://www.americansurnames.us/surnames/muslim_surnames/ (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Abdulwasi, M.; Bhardwaj, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Zawi, M.; Price, J.; Harvey, P.; Banerjee, A.T. An ecological exploration of facilitators to participation in a mosque-based physical activity program for South Asian Muslim women. J. Phys. Act. Health 2018, 15, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickerson, B.D.; Henderson, K.A. Opportunities for promoting youth physical activity: An examination of youth summer camps. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiee, M. As Anti-Islamic Tone Rises in U.S., Muslim Women Learn Self-Defense; Reuters: London, UK, 11 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, T.; Pfister, G.; Jawad, H. (Eds.) Muslim Women and Sport; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bagby, I. National Needs Assessment of Mosques Associated with ISNA & NAIT. Part 1: Mosque Leader Survey; Islamic Society of North America: Plainfield, IL, USA, 2013; Available online: https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/needs_assessment_study.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Fazaka, Y. What is Keeping the Youth Away from the Masjid? The Assembly of Muslim Jurists of America: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: http://www.amjaonline.org/en/academic-research/cat_view/5-contemporary-issues-facing-muslim-youth-in-the-west-2009 (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Public Health England; KIKIT Pathways to Recovery; Birmingham City Council. Guide to Healthy Living: Mosques; Public Health England: London, UK, 2017. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/619891/Guide_to_Healthy_Living_Mosques.PDF (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Padela, A.; Gunter, G.; Killawi, A. Meeting the Healthcare Needs of American Muslims: Challenges and Strategies for Healthcare Settings; Institute for Social Policy and Understanding: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: https://www.ispu.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/620_ISPU_Report_Aasim-Padela_final.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- Sayeed, S.; Al-Adawiya, A.; Bagby, I. The American Mosque 2011. Report Number 3 from the US Mosque Study 2011. Women and the American Mosque; Council on American-Islamic Relations: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Available online: http://www.hartfordinstitute.org/The-American-Mosque-Report-3.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2018).

- UC San Diego School of Medicine Center for Community Health. Faith-Based Wellness: Addressing Health Disparities in African American, Latino and Muslim Communities in San Diego. Available online: https://ucsdcommunityhealth.org/work/faith-based-wellness/ (accessed on 13 November 2018).

- YMCA of San Diego County. Y Women-Only Swim for Muslim Women. Published on 27 June 2012. Available online: https://www.ymca.org/about-y/news-center/programs/y-women-only-swim-muslim-women (accessed on 13 November 2018).

- United Women of East Africa. Dunya Women’s Collaborative. Available online: https://www.uweast.org/category/health-wellbeing/ (accessed on 13 November 2018).

| Category | Centers with Data (n) | Cumulative Camps (n) | Freq (%) | Min | Max | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | 51 | 56 a | 1.0 | 12.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| Sports b | 23 (14.2) | ||||||

| Soccer | 16 (9.9) | ||||||

| Swimming | 15 (9.2) | ||||||

| Hiking | 14 (8.6) | ||||||

| Basketball | 13 (8.0) | ||||||

| Canoeing/Kayaking | 12 (7.4) | ||||||

| Archery | 9 (5.6) | ||||||

| Climbing | 5 (3.1) | ||||||

| Cricket | 5 (3.1) | ||||||

| Volleyball | 5 (3.1) | ||||||

| Other activities c | 45 (27.8) | ||||||

| Camp length (day) | 41 | 47 | 2.0 | 54.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | |

| Camp participants | 51 | 58 | |||||

| Men only | 7 (12.1) | ||||||

| Women only | 5 (8.6) | ||||||

| Other d | 46 (79.3) |

| Category | Centers with Data (n) | Cumulative Classes (n) | Freq (%) | Min | Max | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | 53 | 73 | 1.0 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| Karate | 13 (17.6) | ||||||

| Taekwondo | 10 (13.5) | ||||||

| Fitness a | 9 (12.2) | ||||||

| Pilates/Yoga | 7 (9.5) | ||||||

| Martial arts b | 5 (6.8) | ||||||

| Other activities c | 30 (40.5) | ||||||

| Class duration (min/class) | 35 | 54 | 30.0 | 491.0 | 60.0 | 60.0 | |

| Class frequency (class/wk) | 43 | 61 | 0.25 | 7.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Volume (min/wk) | 53 | 57 | 30.0 | 3435.0 | 120.0 | 120.0 | |

| Class instructor sex | 27 | 41 | |||||

| Male | 27 (65.9) | ||||||

| Female | 14 (34.1) | ||||||

| Class instructor religion | 24 | 33 | |||||

| Muslim | 30 (90.9) | ||||||

| Non-Muslim | 3 (9.1) | ||||||

| Class participants | 53 | 88 | |||||

| Women only | 33 (37.5) | ||||||

| Men only | 17 (19.3) | ||||||

| Other d | 38 (43.2) |

| Category | Centers with Data (n) | Cumulative Programs (n) | Freq (%) | Min | Max | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | 47 | 100 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | |

| Soccer | 27 (27.0) | ||||||

| Basketball | 23 (23.0) | ||||||

| Badminton | 11 (11.0) | ||||||

| Volleyball | 8 (8.0) | ||||||

| Cricket | 5 (5.0) | ||||||

| Table tennis | 5 (5.0) | ||||||

| Other activities a | 21 (21.0) | ||||||

| Practice/game duration (min/session) | 26 | 61 | 30.0 | 240.0 | 120.0 | 60.0 | |

| Practice/game frequency (session/wk) | 33 | 79 | 0.25 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Volume (min/wk) | 24 | 57 | 40.0 | 720.0 | 180.0 | 120.0 | |

| Sport coach sex | 7 | 9 | |||||

| Male | 8 (88.9) | ||||||

| Female | 1 (11.1) | ||||||

| Sport coach religion | 7 | 9 | |||||

| Muslim | 8 (88.9) | ||||||

| Non-Muslim | 1 (11.1) | ||||||

| Program participants | 47 | 151 | |||||

| Men only | 53 (35.1) | ||||||

| Women only | 29 (19.2) | ||||||

| Other b | 69 (45.7) |

| Category | Centers with Data (n) | Cumulative Activities (n) | Freq (%) | Min | Max | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | 90 | 141 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | |

| Sports/athletics a | 25 (17.7) | ||||||

| Hiking | 24 (17.0) | ||||||

| Basketball | 19 (13.5) | ||||||

| Bowling | 12 (8.5) | ||||||

| Laser tag/mini-golf/paintball | 12 (8.5) | ||||||

| Soccer | 7 (5.0) | ||||||

| Canoeing/kayaking | 5 (3.5) | ||||||

| Other activities a | 37 (26.2) | ||||||

| Program participants | 90 | 147 | |||||

| Men only | 36 (24.5) | ||||||

| Women only | 26 (17.7) | ||||||

| Other c | 85 (47.8) |

| Category | Centers with Data (n) | Cumulative Programs (n) | Freq (%) | Min | Max | Med | IQR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programs | 73 | 122 | 1.0 | 8.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Soccer | 19 (15.6) | ||||||

| Basketball | 18 (14.8) | ||||||

| Sports/athletics a | 17 (13.9) | ||||||

| Run/walk | 10 (8.2) | ||||||

| Football | 6 (4.9) | ||||||

| Other activities b | 52 (42.6) | ||||||

| Context (offerings/center) | 73 | 84 | |||||

| General | 27 (32.1) | ||||||

| Specific | 57 (67.9) | ||||||

| Eid/Ramadan | 17 (29.8) | ||||||

| Tournament | 15 (26.3) | ||||||

| Community run/race walk | 11 (19.3) | ||||||

| Other contexts c | |||||||

| Program participants | 73 | 147 | |||||

| Men only | 36 (24.5) | ||||||

| Women only | 26 (17.7) | ||||||

| Other d | 85 (47.8) |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kahan, D. Physical Activity Programming Advertised on Websites of U.S. Islamic Centers: A Content Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112581

Kahan D. Physical Activity Programming Advertised on Websites of U.S. Islamic Centers: A Content Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(11):2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112581

Chicago/Turabian StyleKahan, David. 2018. "Physical Activity Programming Advertised on Websites of U.S. Islamic Centers: A Content Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 11: 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112581

APA StyleKahan, D. (2018). Physical Activity Programming Advertised on Websites of U.S. Islamic Centers: A Content Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2581. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112581