The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- reporting primary quantitative research involving any length of follow-up

- with titles/abstracts mentioning suicide, fatal or non-fatal suicide attempts, or suicidal ideation

- with titles or abstracts mentioning the Greenlandic population or Inuit population

- specifying age-ranges covering men aged 15–29

- specific to the Greenlandic population (those born in Greenland with at least one Greenland-born parent)

- published in English

- specific to Inuit populations in other countries

- presenting data on the age-range 15–29 but not specific to men

- focusing on non-fatal suicide attempt or suicidal ideation but not suicide

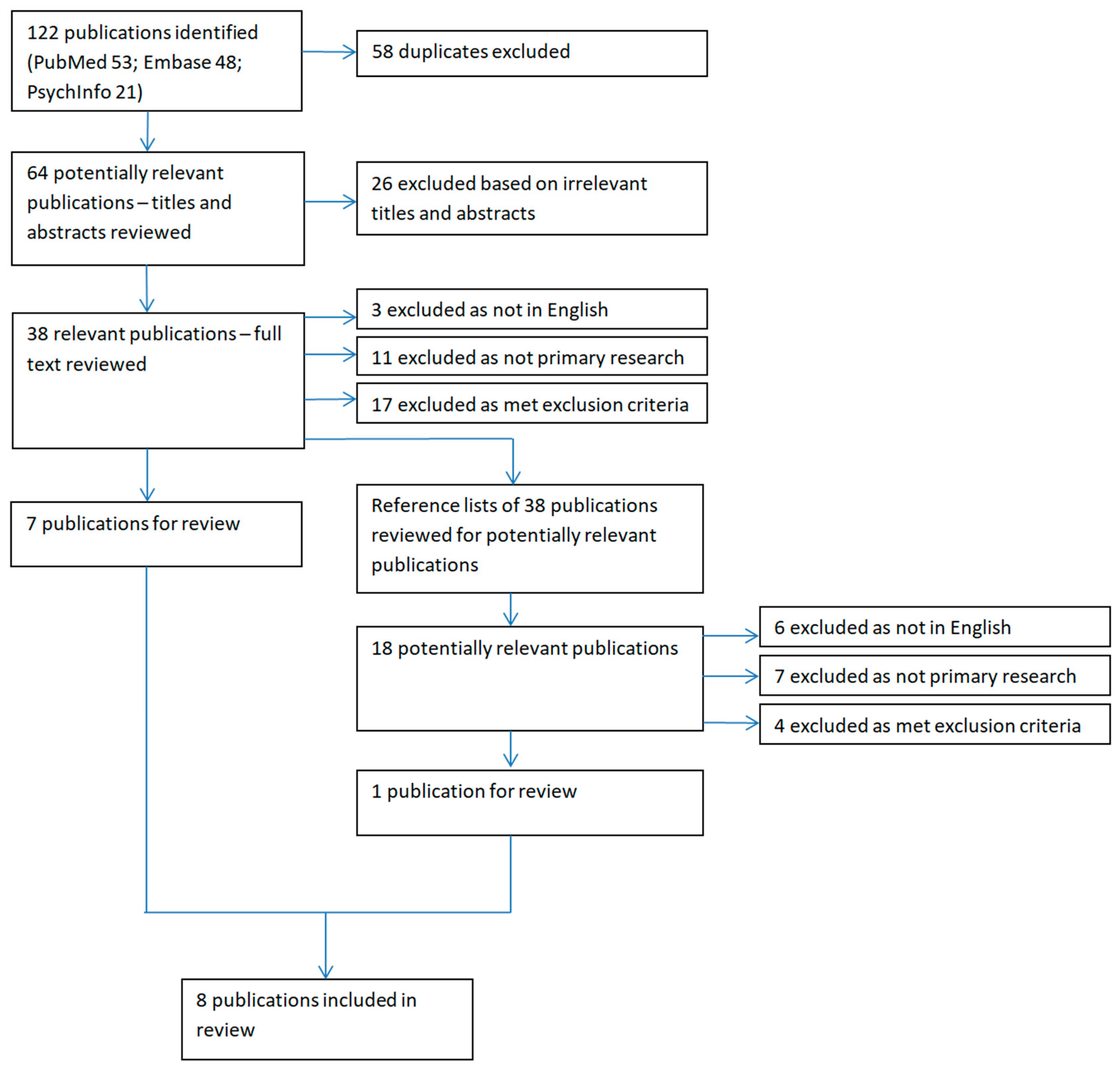

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Studies Identified

3.2. Study Quality

3.3. Risk of Bias across Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.4.1. Aggregated Data for Specific Periods

3.4.2. Temporal Trends

3.4.3. Period Effects

3.4.4. Regional Variation

3.4.5. Risk Factors

3.4.6. Suicide Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Findings in the Context of Other Studies

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

4.3.1. Strengths

4.3.2. Limitations at Study Level

4.3.3. Limitations at Review Level

4.4. Policy Implications

4.5. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pitman, A.; Krysinska, K.; Osborn, D.; King, M. Suicide in young men. Lancet 2012, 379, 2383–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, P.Y.; Delgado, R.A.; Pringle, B.A.; Roca, C.; Phillips, A. Suicide prevention in Arctic indigenous communities. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, T.K.; Revich, B.; Soininen, L. Suicide in circumpolar regions: An introduction and overview. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 27349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moltke, I.; Fumagalli, M.; Korneliussen, T.S.; Crawford, J.E.; Bjerregaard, P.; Jørgensen, M.E.; Grarup, N.; Gulløv, H.C.; Linneberg, A.; Pedersen, O.; et al. Uncovering the genetic history of the present-day Greenlandic population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 96, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- StatbankGreenland. National Board of Health Mortality Statistics 1990–2013. Available online: http://bank.stat.gl/ (accessed on 24 April 2018).

- WHO. Country Reports and Charts. Available online: http://www.who.int/topics/suicide/en/ (accessed on 27 April 2018).

- WHO. Global Health Observatory (GHO) Data: Suicide Rates per (100,000 Population). Available online: http://www.who.int/gho/mental_health/suicide_rates_crude/en/ (accessed on 17 April 2018).

- White, A.; Holmes, M. Patterns of mortality across 44 countries among men and women aged 15–44 years. J. Mens Health Gender 2006, 3, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAARISA. Proposal for a National Strategy for the Prevention of Suicides in Greenland; PAARISA: Nuuk, Greenland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, P.; Larsen, C.V. Three lifestyle-related issues of major significance for public health among the Inuit in contemporary Greenland: A review of adverse childhood conditions, obesity, and smoking in a period of social transition. Public Health Rev. 2018, 39, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertelsen, A. Gronlandsk medicinsk statistik og nosografi (medical statistics and nosography of Greenland). Meddl. Gronland 1935, 1, 58–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lynge, I. Suicide in Greenland. Arct. Med. Res. 1985, 40, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kapur, N.; Cooper, J.; O’Connor, R.C.; Hawton, K. Non-suicidal self-injury v. Attempted suicide: New diagnosis or false dichotomy? Br. J. Psychiatry 2013, 202, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.; Kapur, N.; Webb, R.; Lawlor, M.; Guthrie, E.; Mackway-Jones, K.; Appleby, L. Suicide after deliberate self-harm: A 4-year cohort study. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elm, E.v.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.P.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007, 335, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerregaard, P.; Larsen, C. Time trend by region of suicides and suicidal thoughts among Greenland Inuit. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 26053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grove, O.; Lynge, J. Suicide and attempted suicide in Greenland. A controlled study in Nuuk (godthaab). Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1979, 60, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorksten, K.S.; Bjerregaard, P.; Kripke, D.F. Suicides in the midnight sun--a study of seasonality in suicides in West Greenland. Psychiatry Res. 2005, 133, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerregaard, P.; Lynge, I. Suicide—A challenge in modern Greenland. Arch. Suicide Res. 2006, 10, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorslund, J. Suicide among Inuit youth in Greenland 1977–1986. Arct. Med. Res. 1991, 50, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Thorslund, J. Inuit suicides in Greenland. Arct. Med. Res. 1990, 49, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Leineweber, M.; Arensman, E. Culture change and mental health: The epidemiology of suicide in Greenland. Arch. Suicide Res. 2003, 7, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, R.D.; Bunker, J.B.; Wachs, M. Distinguishing aging, period and cohort effects in longitudinal studies of elderly populations. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 1977, 11, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Multisite Intervention Study on Suicidal Behaviours-Supre-Miss: Protocol of Supre-Miss; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Box, J.E. Survey of Greenland instrumental temperature records: 1873–2001. Int. J. Climatol. 2002, 22, 1829–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Greenland. Politics in Greenland. Available online: http://naalakkersuisut.gl/en/About-government-of-greenland/About-Greenland/Politics-in-Greenland (accessed on 30 September 2018).

- Bjerregaard, P. Rapid sociocultural change and health in the Arctic. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2001, 60, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leighton, A.H.; Hughes, C.C. Notes on Eskimo patterns of suicide. Southwest. J. Anthropol. 1955, 11, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silviken, A.; Haldorsen, T.; Kvernmo, S. Suicide among indigenous Sami in Arctic Norway, 1970–1998. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 21, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EchoHawk, M. Suicide prevention efforts in one area of Indian health service, USA. Arch. Suicide Res. 2006, 10, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boothroyd, L.J.; Kirmayer, L.J.; Spreng, S.; Malus, M.; Hodgins, S. Completed suicides among the Inuit of northern Quebec, 1982–1996: A case-control study. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2001, 165, 749–755. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, M. Suicide among young Alaska native men: Community risk factors and alcohol control. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, S329–S335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, P. Suicide risk in relation to level of urbanicity—A population-based linkage study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 34, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynge, I.; Mortensen, P.B.; Munk-Jorgensen, P. Mental disorders in the Greenlandic population. A register study. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 1999, 58, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thorslund, J.; Misfeldt, J. On suicide statistics. Arct. Med. Res. 1989, 48, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, P.; Curtis, T. Cultural change and mental health in Greenland: The association of childhood conditions, language, and urbanization with mental health and suicidal thoughts among the Inuit of Greenland. Soc. Sci. Med. 2002, 54, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderstad, A.R.; Eliassen, B.M.; Melhus, M. Prevalence of self-reported suicidal thoughts in SLiCA. The survey of living condition in the Arctic (SLiCA). Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 10226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Fevre, A.C. The challenge of reducing youth suicide in Greenland—Interventions, strategies and roads to be explored. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2004, 63 (Suppl. 2), 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C.M.; Sarchiapone, M.; Postuvan, V.; Volker, D.; Roskar, S.; Grum, A.T.; Carli, V.; McDaid, D.; O’connor, R.; Maxwell, M. Best practice elements of multilevel suicide prevention strategies. Crisis 2011, 32, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redvers, J.; Bjerregaard, P.; Eriksen, H.; Fanian, S.; Healey, G.; Hiratsuka, V.; Jong, M.; Larsen, C.V.L.; Linton, J.; Pollock, N. A scoping review of indigenous suicide prevention in circumpolar regions. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2015, 74, 27509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalsman, G.; Hawton, K.; Wasserman, D.; van Heeringen, K.; Arensman, E.; Sarchiapone, M.; Carli, V.; Höschl, C.; Barzilay, R.; Balazs, J. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soule, S. An Evaluation of the Implementation of Greenland’s National Strategy for Suicide Prevention with Recommendations for the Future; PAARISA: Nuuk, Greenland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Björkstén, K.S.; Bjerregaard, P. Season of birth is different in Inuit suicide victims born into traditional than into modern lifestyle: A register study from Greenland. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leineweber, M.; Bjerregaard, P.; Baerveldt, C.; Voestermans, P. Suicide in a society in transition. Int. J. Circumpolar Health 2001, 60, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bolliger, L.; Gulis, G. The tragedy of becoming tired of living: Youth and young adults’ suicide in Greenland and Denmark. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2018, 64, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author and Title | Design, Setting and Objectives | Participants | Variables | Results (Those Relevant to Research Question) | Bias and Limitations | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grove and Lynge, 1979 Suicide and attempted suicide in Greenland. A controlled study in Nuuk [19]. | Case-control study. Capital of Greenland, Nuuk, in 1972 and 1973. Aimed to identify risk factors for suicide and suicide attempt in cases of fatal and non-fatal suicide attempt compared to general population never suicidal controls. | Cases: all Greenlanders in Nuuk who died by suicide or attempted suicide in 1972 and 1973 (n = 1576 males + 1697 females), with attempted suicide defined as that requiring hospital admission. Controls: Nuuk residents admitted to hospital for a somatic disease or pregnancy, matched by gender and age group for each case, but with no history of suicide attempt. | Information on suicide cases collected from available records “coming to the attention of any authority in the district of Nuuk.” i.e., death certificates, and police reports. Information on suicide attempt cases was additionally collected from hospital files, police reports, and crime registers to capture unvalidated measures of family composition, childhood, atmosphere in parental home, alcohol consumption, criminal records, exposure to attempted or completed suicide, marital status, inter-racial marriage, psychiatric history, obstetric history, and method of suicide attempt. Age groupings used: 15–19; 20–24; 25–39; ≥40. | Measures presented for young men: absolute numbers of suicide deaths. Findings: 12 suicides recorded in Nuuk during 1972 and 1973: 10 were in men. Age-specific data identified 4 suicides in men aged 15–24 over this period (compared with 2 for women), and 16 suicide attempts in men of the same age. Suicide rates for 4 age-groups were estimated for both genders combined (300 cases of suicide per 100,000 inhabitants in men and women aged 15–19; 173 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in men and women aged 20–24). Suicide rates for men and women aged 25–39 were 226 per 100,000, whilst those for men and women of 40 and over were 54. Risk factors were not separated out by age group or gender. Ratios of suicide attempts to suicide deaths were not presented, but on direct calculation were: 5:3 in men aged 15–19 (compared with 10:1 in similar aged women) 11:1 in men aged 20–24 (compared with 12:1 in similar aged women). 10:5 in men aged 25–39 (compared with 11:0 in similar aged women). | Outcomes were separated out for men and women only in relation to absolute numbers of suicide deaths. Unclear whether method of identifying suicide cases in Nuuk in 1972–1973 was comprehensive. Presented age-specific suicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants (of Nuuk) per year, using census mid-estimates of the population denominator in each age band. Findings from the population of Nuuk may not be generalizable to the whole Greenlandic the population due to urban-rural differences. Estimates of the general population denominator for 1973 were based on mid-point interpolations between 1970 and 1976 census data. These were therefore unreliable as mid-point population estimates would fail to take into account changing migration and fertility patterns. | Little can be concluded about suicide epidemiology in young men in the capital of Greenland as absolute numbers of suicides in men of different age groups were too low to attempt meaningful comparisons. Estimates of age-specific suicide rates were not specific to men, and used an unreliable estimate of the denominator. Direct calculation of the ratios of suicide attempts to suicide deaths indicate that the ratio increases from 5:3 for men aged 15–19 to 11:1 in men aged 20–24 and then falls to 10:5 for men aged 25–39. |

| Lynge, 1985 Suicide in Greenland [12] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases. Whole of Greenland during the period 1974–1984. To describe suicide rates in Greenland. | Cases: All those aged 15 and above who were born in Greenland and died by suicide in 1974–1984, as identified from death certificates and police reports (n = 318). | Data on age, gender and place of residence of those dying by suicide, based on police reports and death certificates, as well as unvalidated measures of known motives and whether alcohol was involved in the suicide. Age groupings used: 15–19; 20–24; 25–39; ≥40 | Measures presented for young men: absolute numbers of suicide deaths; suicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants per year. Findings: 318 total suicides in men and women over this period. 256 were in men, with the highest absolute numbers of suicides (n = 97) in men in the age group 20–24. Age and gender-specific suicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants per year were highest in men age 20–24 (387 per 100,000). The suicide rate in men aged 15–19 (151 per 100,000) was higher than that in men aged 40 and over (73 per 100,000) but lower than that in men aged 20–24 (162 per 100,000). The suicide rates for women were lower than for men in all age groups (44 per 100,000 in women aged 15–19; 94 per 100,000 in women aged 20–24). | Author acknowledges that due to non-systematic collection of death certificates, some cases of suicide may have been missed. Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Presented crude suicide rates for 100,000 inhabitants per year. | For the period 1974–1984 suicide rates in young men aged 20–24 were the highest of all age and gender groups in Greenland at 387 per 100,000 inhabitants per year, compared with 151 per 100,000 for men aged 15–19, 162 per 100,000 for men aged 25–39, and 73 per 100,000 in men over 40. The gender gap in suicide rates over this period was greatest in the age group 20–24 at 387 versus 94 per 100,000. Year on year rates were not presented so no information was provided on temporal trends. |

| Thorslund, 1990 Inuit Suicides in Greenland [23] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases. Whole of Greenland from 1977–1986. To describe the epidemiology of suicide among Greenlandic Inuit. | Cases: All recorded suicides in Greenland from 1977–1986 among Greenland-born individuals (n = 403), using death certificates and police reports. | Data on age, gender, occupation, marital status, parental status, psychiatric history, substance misuse history, and circumstances of the death, history of suicidal behaviour, derived from public files, death certificates, municipal welfare office records, and police reports. Age groupings used: histogram presented data for a continuous measure of age from 10 to 60 | Measures presented for young men: average suicide rates per 100,000 population per year. Findings: 403 suicides analysed over a 10 year period, of which 326 were of men (of any age). Visual plots of average suicide rates per 100,000 population per year showed that suicide risk increased sharply from the ages of approximately 15–17, peaking at approximately age 20, falling from approximately age 23, and with further peaks in the mid-30s and the 50s. The great disparity between male and female suicide rates from the age of about 17 diminished by approximately age 27. Data for risk factors, including occupation, was not separated out by gender or age group. | Little information was presented regarding the reliability of routine data. Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Presented crude suicide rates for 100,000 inhabitants, as an average per year using data over a 10 year period 1977–1986. Data for risk factors was not presented by gender or age group. | Over the 10 year period 1977–1986, men aged approximately 20 to 23 had the highest suicide rates in the Greenlandic population, greatly exceeding those for women of the same age. |

| Thorslund, 1991Suicide Among Inuit Youth in Greenland 1977–1986 [22] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases. Whole of Greenland from 1977–1986. To describe risk factors for suicide among youths aged 15–30 in Greenland. | Cases: All suicides in Greenland from 1977–1986 of youths aged 15–30 (n = 287), using death certificates and police reports. Controls: n = 320 randomly selected young people living in Greenland, sampled via postal questionnaire in 1988. | Data collected on place of residence (town/village), occupation, presence of alcohol in blood, and personal circumstances prior to death, based on public files (police reports, death certificates and social service departments), Public Databases (Public Health Department and Central Bureau of Statistics) and from questionnaires (for controls). Age groupings used: 15–30. | Measures presented for young men: crude average number of suicides per year per 100,000 inhabitants (for both genders); proportions of suicide deaths by gender and occupational group (aged 15–30); proportions of suicide deaths by gender and recent psychosocial stressor (all ages). Findings: In a sub-sample of youth dying by suicide aged 15–30 in 1982–1986 for which occupational data were presented (n = 184), the majority were men (n = 144; 78%). Of this sub-sample, 26% of men were hunters/fishermen versus 0% of women (and 15% of male controls), 21% were unskilled workers vs 13% of women (and 37% of male controls), 24% were unemployed vs 38% of women (and 3% of male controls), and 5% were white collar workers vs 10% of women (and 13% of male controls). No statistical tests were presented for these comparisons. For men and women dying by suicide aged 15–30 from 1977–1986, in over 30% of cases there were reports of personal problems with a spouse prior to the suicide, with the text indicating that this was more common in women (but not whether this was statistically significant). The text also indicated that in 20% of male suicides there was a history of rejection from parents or friends “or other shameful situations” prior to the suicide. | Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Little information presented regarding the reliability of routine data. Very little information provided on the characteristics of the control group used in the comparison of proportions of men and women dying by suicide by occupational group (derived from a survey of Greenlandic residents in 1988). No statistical tests presented for comparisons between men and women aged 15–30, or between cases and controls. Data on risk factors were not presented by gender. Presented crude average number of suicides per year per 100,000 inhabitants (for both genders). | From 1982–1986, 78% of suicides among youth aged 15–30 were in men. These men primarily worked in traditional hunting/fishing jobs, unskilled jobs, or were unemployed. On the basis of cases of suicide in those aged 15–30 from 1977–1986, rejection by parents of friends or “other shameful situations” were implicated in 20% of male suicide cases aged 15–30. |

| Leineweber & Arensman 2003 Culture Change and Mental Health: The Epidemiology of Suicide in Greenland [24] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases. Whole of Greenland from 1972–1995, with age- and gender-specific data only presented for the years 1990–1995. To describe suicide rates in Greenland. | Cases: All suicides in Greenland from 1972–1995 of Greenland-born individuals, using the register of causes of death based on death certificates certified by a physician using ICD code diagnoses. | Data collected on gender, age and place of residence were drawn from a computerized register on causes of death for persons born in Greenland. Population suicide rates were age-standardised by direct standardisation. Age groupings used: histograms presented plots for ages 10–15; 15–19; 20–24; 25–29; 30–39; 40–49; 50–59; 60+ (or 15–19; 20–24; 25–29; ≥30) | Measures presented for young men: Visual plots of suicide rates per 100,000 population by sex and age-group. Findings: Visual plotting of suicide rates per 100,000 population by age-group and sex in Greenland in the period 1990–1995 showed that rates in men aged 15–24 were the highest of all age-groups for either gender; approximately 460 per 100,000 population for those aged 15–19, declining with age, but remaining above 400 per 100,000 for those aged 20–24, and approximately 300 per 100,000 for men aged 25–29. Rates for men were higher than for women in all age groups. Risk factors for suicide were not separated out by age-group or gender. | Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Risk factors for suicide were not separated out by age-group or gender. | From 1990–1995 suicide rates in men aged 15–19 and 20–24 were the two highest ranking age groups for all age-groups in either gender. Rates for men aged 15–24 were approximately 460 per 100,000, and declined with age, remaining higher for men than women in all age groups. |

| Bjorksten, Bjerregaard et al., (2005) Suicides in the midnight sun—A study of seasonality in suicides in West Greenland [20] | Suicide data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases only for West Greenland, 1968–1995, with rates for 7 specific years reported. To investigate whether there is evidence for seasonality of suicide rates in West Greenland. | Cases: Suicides of people of any age living in towns and settlements in West Greenland, as recorded in the register of causes of death in Greenland, and population registers from the National Institute of Public Health in Copenhagen were analysed (n = 833). | Data collected on age, gender, suicide date, country of birth (Greenland/Denmark), residence (town/settlement), latitude, and whether alcohol contributed to their death, based computerised registers on causes of death in Greenland and population registers from the National Institute of Public Health in Copenhagen. Age groupings used: 0–14; 15–24; 25–34; 35–59; ≥60. | Measures presented for young men: suicide rates per 100,000 person-years by age-group; seasonality of suicides by gender (men of all ages) and age group (all men and women ≤ 24 vs. >24). Findings: Of 684 total suicides in men over the period 1968 to 1995, the median age of cases was 25 and the age range was 11 to 84 years. When considering the specific years 1970, 1976, 1982, 1987, 1990, 1993, and 1995 (for which detailed population data were available, allowing calculation of suicide rates per 100,000 person-years), results showed that men aged 15–24 had the highest suicide rates between 1976 and 1995, peaking at 577 per 100,000 person-years in 1990. For the period 1970 to 1995, the longitudinal picture for male suicide rates was one of great change. In 1970, all 122 suicide cases had been men aged 35–59 years of age, with the overall suicide rate for men of all ages at 22 per 100,000 inhabitants per year. From 1976 to 1995, the overall suicide rate in men climbed from 80 per 100,000 in 1976 to a maximum value of 214 per 100,000 in 1990. For young men aged 15–24, suicide rates climbed from 0 in 1970 to 249 per 100,000 in 1976 to a maximum of 577 per 100,000 in 1990. This age group had the highest suicide rates of all male age groups during 1976–1995, plateauing at 238 per 100,000 in 1995. Men of 25–34 years of age also had high suicide rates from 1976 on, peaking at 297 per 100,000 in 1990. In 1995 suicide rates for men aged 15–24 remained the highest at 238 per 100,000, but disparities with those for men aged 25–34 were less at 219 per 100,000 person-years. Analysis of seasonality of suicides was examined for men (all ages), finding a statistically significant midsummer peak, and for men and women combined aged ≤ 24, finding no significant seasonality. Risk factors for suicide were not broken down by age-group or gender. | Estimates of suicide rates by age group for specific years over the period 1968–1995 may not be generalisable to East Greenland or Nuuk, where suicide rates tended to be higher in the 1970s and 1980s. Suicide rates presented as actual numbers of suicides per year for the period 1968–1995, and as crude rates per 100,000 person-years for the specific years 1970, 1976, 1982, 1987, 1990, 1993, and 1995. The finding of no significant seasonality by age may have been due to low numbers | No observations can be made about seasonality of suicide in young men specifically, but there was a significant midsummer peak for men of all ages. For young people, no seasonality was observed in men and women (combined) aged 24 and under for the period 1968–1995. In the whole population, significant seasonality was observed, with a peak in late June and lowest rates in the darkest months (December to February). From 1976–1995 suicide rates were highest in men aged 15–24, peaking at 577 per 100,000 in 1990. In 1995 they remained the highest for all male age groups at 238 per 100,000 but with less of a disparity with rates for men aged 25–34. |

| Bjerregaard and Lynge (2006) Suicide—A Challenge in Modern Greenland [21] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases. Whole of Greenland from 1968–1999. To describe suicide rates in young men in Greenland in 1968–1999, compared with those in other demographic groups. Study also presented linked cross-sectional population-based survey data from 2 population surveys in Greenland (in 1993–1994 and 1999–2001) describing past year prevalence of suicidal thoughts (not meeting search criteria for the current study but brief details given here). | Cases: All suicides in Greenland from 1968–1999 of Greenland-born individuals (n = 1203), using the register of causes of death based on death certificates certified by a physician using diagnoses based on ICD-8 (1968-1993) or ICD-10 (1994–1999). | Data collected on age, gender, and place of residence. Age groupings used: histogram presented data for a continuous measure of age from 0 to approximately 85, with points specified for 0–4; 10–14; 20–24; 30–24; 40–44; 50–54; 60–64; 70 | Measures presented for young men: visual plots of age-specific suicide rates per 100,000 person-years; visual plots of youth suicide rates (aged 15–29) for men per 100,000 births in each cohort. Findings: Overall for the period 1968–1999 and all age groups, suicide rates were 4.3 times higher in men than women. Visual plots of age-specific suicide rates for the aggregated period 1990–1999 showed suicide rates to be considerably higher in men aged 15–24 in Greenland (approximately 470 per 100,000 person-years) than for men of a similar age in Denmark and for women of a similar age in Greenland and in Denmark. This disparity continued up until approximately the age 45, when rates in all four groups converged. Youth suicide rates (aged 15–29) for men in the 1950 birth cohort were plotted as approximately 10 per 100,000 births in that cohort, rising to approximately 60 per 100,000 births in the 1978 birth cohort. Although gender-specific data were not presented, visual plots showed that youth suicide rates (aged 15–29) in East Greenland continued to rise from 1975–1979 (approximately 200 per 100,000 person years) to 1995–1999 (approximately 800 per 100,000 person years), in comparison to West Greenland and the capital Nuuk where they plateaued or fell slightly (to between 100 and 200 per 100,000 person years in 1995–1999). Other risk factors for suicide were not broken down by age-group or gender. Additional analysis of data from population surveys called out in 1993–1994 and 1999–2001 showed that men aged 18–24 were significantly less likely that same-aged women to report lifetime suicidal thoughts (19% versus 33%; p = 0.03). At age groups above 25 this gender difference was not statistically significant. | Figures in text did not match those in graphical presentations. Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Suicide rates presented as crude rates per 100,000 person-years for blocks of 5 years, or as crude rates per 100,000 births in a birth cohort. | Aggregated data for 1990–1999 show that suicide rates in young men aged 15–24 were much higher than those for men in other age groups and for men and women of the same age in Denmark, peaking at 450–500 per 100,000 person-years. This pattern differed from that in Denmark, where suicide rates rose across the age groups for men and women, and where a much lower ratio of male:female suicides was reported (1.8 in Denmark versus 4.3 in Greenland). There was evidence that male youth suicide rates (in the age group 15–29) were higher in men born in later cohorts (downstream of sociocultural change), as evidenced in data from cohorts born from 1950 to 1978. Regional variations in youth suicide were not broken down by gender, but suggested that young people in remote areas of East Greenland had higher suicide rates, which continued to rise, whilst youth suicide rates had peaked in the capital, Nuuk, in the early 1980s, and plateaued in West Greenland throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Population survey data from 1993–1994 and 1999–2001 suggested that although suicide rates in young men aged 15–24 were considerably higher than those for women of that age in Greenland, women were significantly more likely to report lifetime suicidal thoughts. |

| Bjerregaard & Larson (2015) Time trend by region of suicides and suicidal thoughts among Greenland Inuit [18] | Aggregated data from annual cross-sectional studies of suicide cases, averaging out rates over periods of between 5 and 30 years Study also presented linked cross-sectional population-based survey data from 2 population surveys in Greenland (in 1993–1994 and 2005–2010) describing past year prevalence of suicidal thoughts (not meeting search criteria for the current study but brief details given here). Whole of Greenland from 1970–2011.To describe time trends in suicide rates (and past year prevalence of suicidal thoughts in 1993–1994 and 2005–2010) in Greenland from 1970 to 2011 | Cases: All suicides in Greenlandic residents from 1901–2011 (n = 1678), based on routine registry data from the Greenland registry of causes of death. General population sample of Greenlandic residents sampled 1993–1994 and 2005–2010 using the same instrument, and overlapping geographical sampling frames, to collect data on self-reported past year prevalence of suicidal thoughts, with linkage of individuals in cross-sectional surveys to subsequent suicides. | Data collected on age, gender, and region of residence for all suicide cases from 1901–2011. Survey data collected on age, gender, and past year prevalence of suicidal thoughts in two cross-sectional samples. Age groupings used: 10–14; 15–19; 20–24; 25–29; 30–34; 35–44; 45–54; ≥55 | Measures presented for young men: suicide rates per 100,000 person-years by age-group (tabulated and visual plots) Findings: Suicide rates for men aged 20–24 were the highest of all male age groups for the period 2000–2011 (at 426 per 100,000 person-years over this whole 12 year period), compared with 297 per 100,000 person years for men aged 15–19 and 251 for men aged 25–29. Suicide rates for men aged 55 and above were the lowest of all male age groups (at 74 per 100,000 person years). Visual plots of suicide rates for men and women by age group for the period 1970 to 2011 also show that rates were highest for men aged 20–24 (at approximately 400 per 100,000 person years). NB: We clarified with the first author that the suicide data presented in his table II are from the registry of causes of death and cover 2000–2011 only, to be comparable to the survey data on suicidal thoughts. He confirmed that the suicide data presented in Figure 1 are also derived from the registry of causes of death but cover the whole time range of the registry, which at that time was 1970–2011. There is hence some overlap between the data from these two sources, and the age pattern was similar in the shorter period and over the whole period. Age patterning of high risk groups for past-year suicidal thoughts mirrored that for suicide rates in men, with the highest rate in men aged 20–24 at 136 per 1000 participants. The proportion of women with past-year suicidal thoughts was greatest for women aged 15–19 (188 per 1000 participants) and fell with increasing age. Age- and gender-specific suicide rates were not presented by region of residence, but the text indicated that male and female patterns were similar to the overall pattern. This pattern, since the 1980s, has been for suicide rates for men, women, and overall to have been significantly higher in East and North Greenland than in West Greenland or the capital, Nuuk. Association between past year suicidal ideation and subsequent suicide was not presented by gender or age group. | Data for an aggregated period obscured year on year changes. Suicide rates presented as crude rates per 100,000 person-years for blocks of between 5 and 30 years. Source and quality of data from 1970–2011 not qualified. Due to small absolute numbers of completed suicides, there was insufficient statistical power to stratify analyses on several levels simultaneously e.g., sex and region. Unclear whether survey instrument validated. [Respondents in the two surveys, and within the same sampling period, could have been sampled twice. No discussion of response rate, recall bias, or social desirability bias.] | Suicide rates for men aged 20–24 were the highest of all age groups for both genders over the 41 year period 1970 to 2011 (at approximately 400 per 100,000 person years), and when considered over the shorter 12 year period of 2000–2011 (at 426 per 100,000 person-years). Age groups at highest risk of suicide match those at highest risk of suicidal thoughts for men. |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sargeant, H.; Forsyth, R.; Pitman, A. The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112442

Sargeant H, Forsyth R, Pitman A. The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(11):2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112442

Chicago/Turabian StyleSargeant, Hannah, Rebecca Forsyth, and Alexandra Pitman. 2018. "The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 11: 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112442

APA StyleSargeant, H., Forsyth, R., & Pitman, A. (2018). The Epidemiology of Suicide in Young Men in Greenland: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2442. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112442