Electronic Waste Governance under “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong and Mainland China

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Study Background

1.2. Policy Networks for Exploring the Models of WEEE Management

1.3. Previous Related Studies

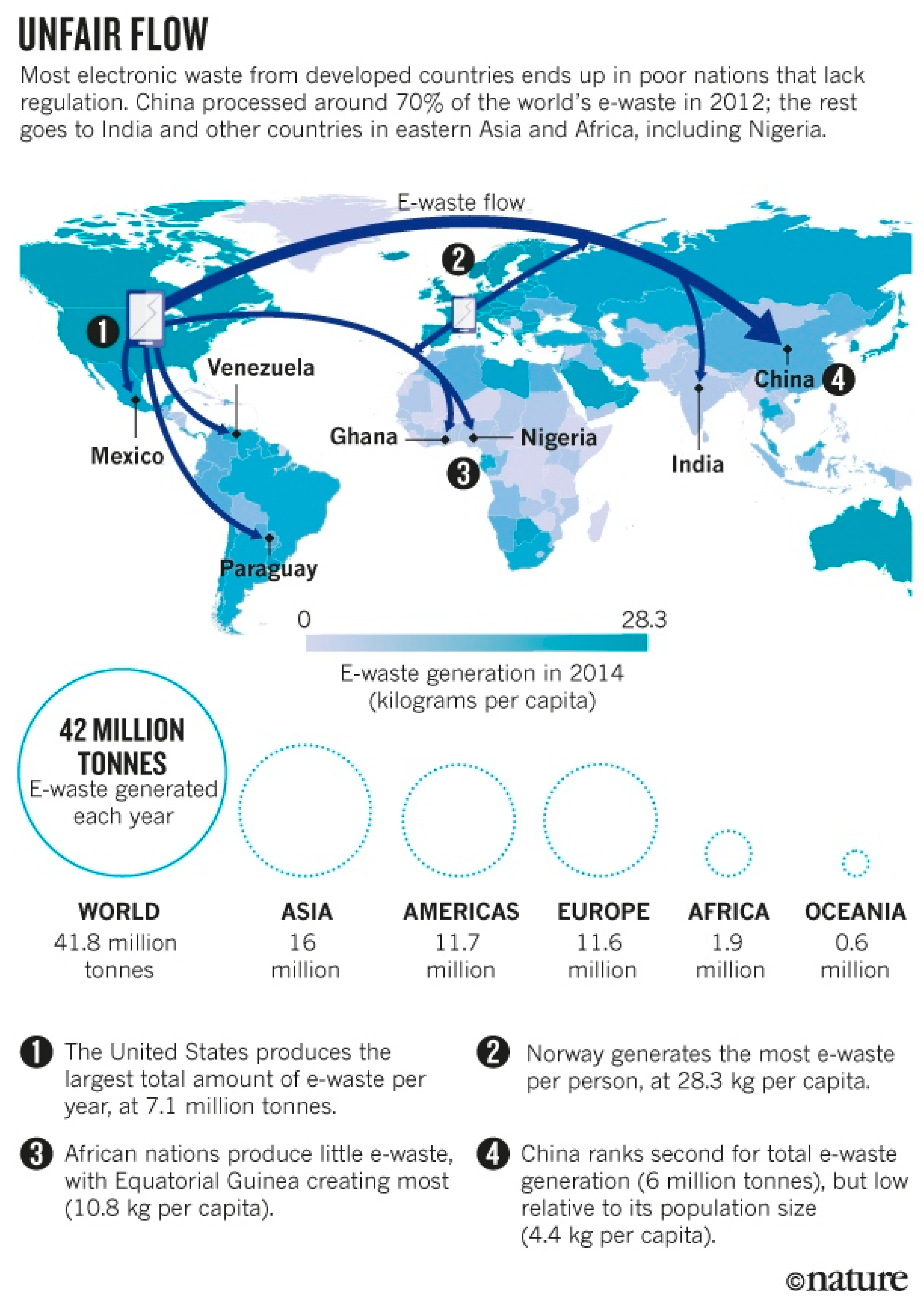

1.3.1. Previous Studies on E-Waste Impacts and Management

1.3.2. Transboundary Environmental Collaboration between Hong Kong and China

2. Methodology and Case Studies

2.1. E-Waste Governance: An Explanatory Framework

- (i)

- e-waste disposal and treatment;

- (ii)

- e-waste generation.

- (i)

- involvement of actors (e.g., public and private actors).

- (i)

- institutional arrangements for e-waste management.

2.2. A Case Study of E-Waste Management in Hong Kong and China

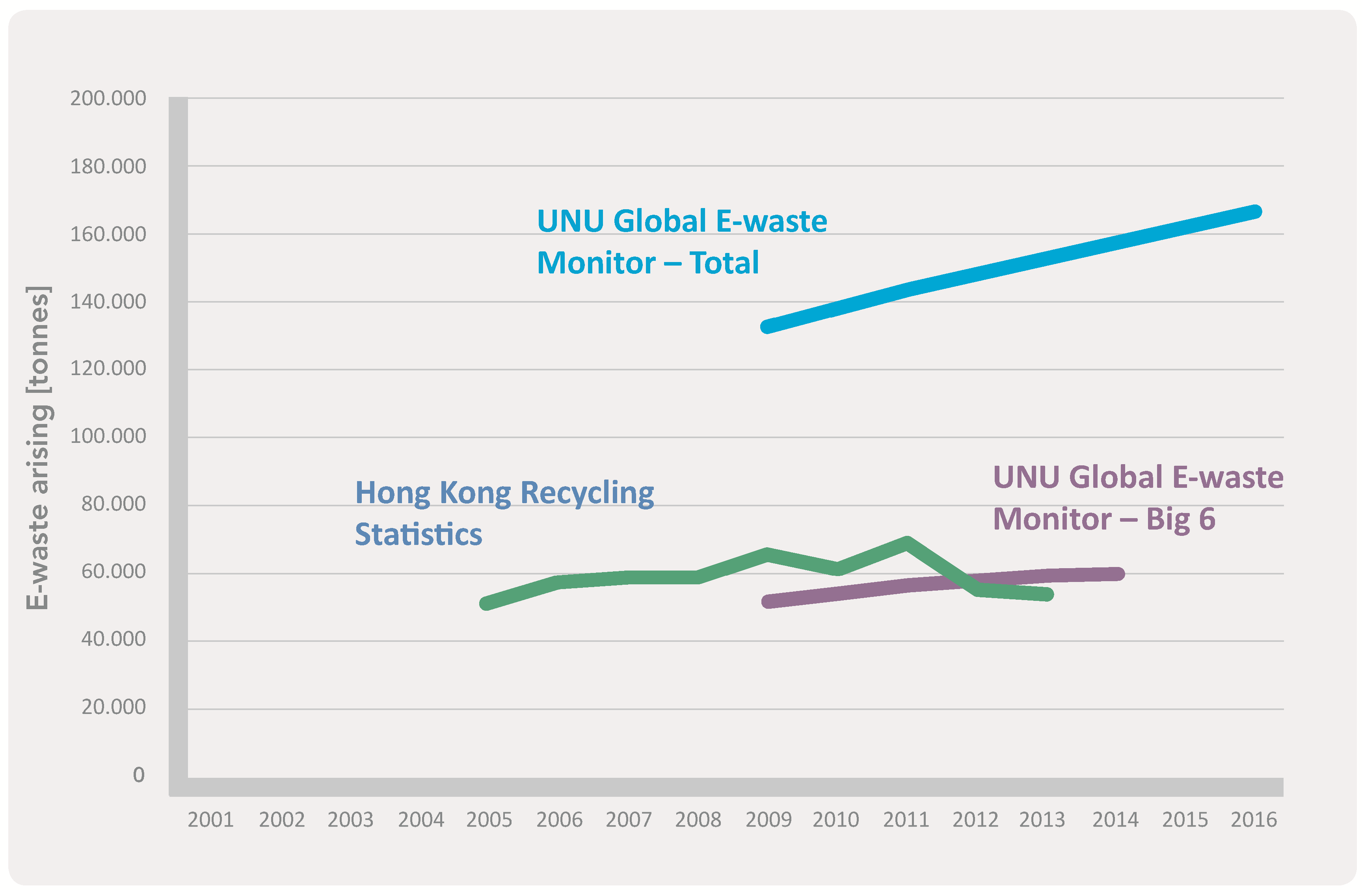

2.2.1. E-Waste Generation and Composition

2.2.2. E-Waste Collection and Recycling

2.2.3. E-Waste Treatment and Disposal

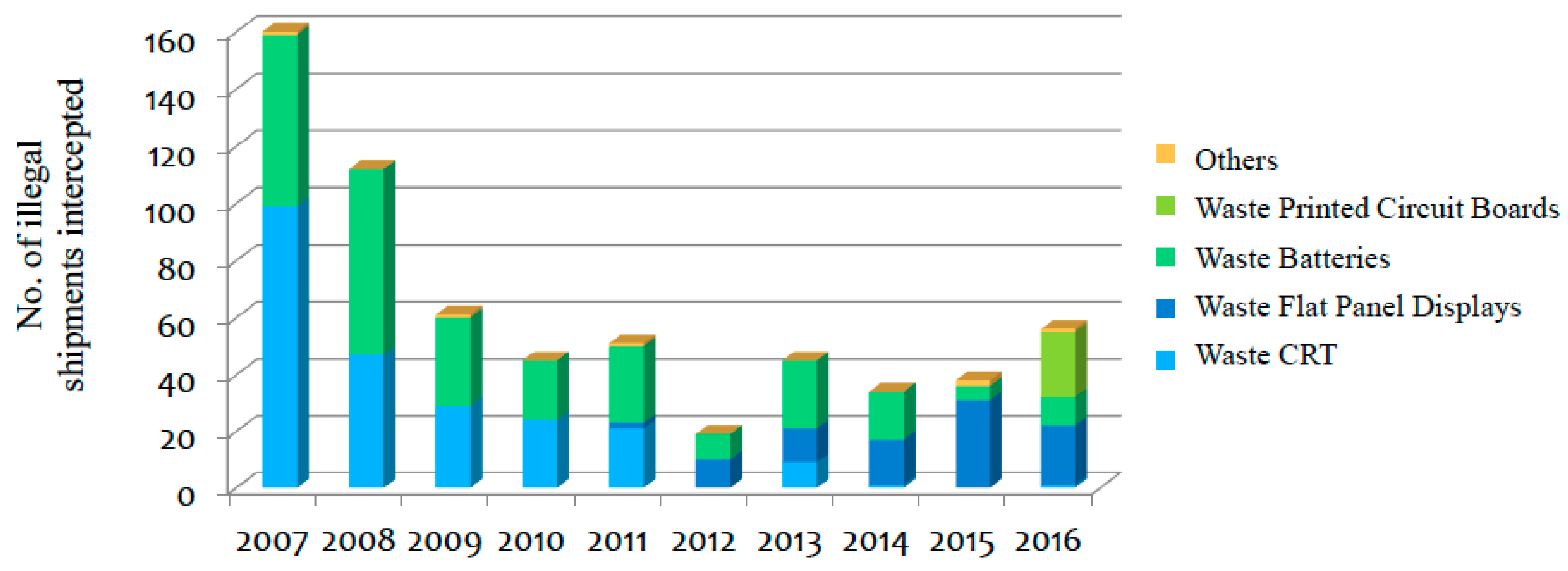

2.2.4. Regulatory Policies for E-Waste

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kennedy, J. Illegal Trade in Toxic E-Waste to Rise Sharply: Study; Chinadialogue: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Waste Electrical & Electronic Equipment (WEEE). European Comission. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/weee/index_en.htm (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- China: The Electronic Wastebasket of the World. Available online: https://edition.cnn.com/2013/05/30/world/asia/china-electronic-waste-e-waste/index.html (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- Greenpeace. Guiyu: An E-Waste Nightmare; Greenpeace International: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- China Officially Issued a Ban on “Foreign Garbage” in 2018, Hong Kong’s Garbage Recycling Industry Is about to Transform. Available online: http://huanbao.ne21.com/show-1028.html (accessed on 24 June 2018).

- Database of Laws and Regulations. Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Prevention and Control of Environmental Pollution by Solid Waste; Ministry of Commerce People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- General Office of the State Council. Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Issuing the Implementation Plan for Prohibiting the Entry of Foreign Garbage and Advancing the Reform of the Solid Waste Import Administration System; General Office of the State Council: Beijing, China, 2007.

- U.S. Environmental Group Conducted Transnational Investigation, Hong Kong Turns to Global E-Waste Dumpsite. Available online: https://www.hk01.com/%E7%A4%BE%E6%9C%83%E6%96%B0%E8%81%9E/22766/01%E7%8D%A8%E5%AE%B6-%E9%A6%99%E6%B8%AF01-%E7%BE%8E%E5%9C%8B%E7%92%B0%E5%9C%98%E8%B7%A8%E5%9C%8B%E8%AA%BF%E6%9F%A5-%E6%B8%AF%E6%B7%AA%E5%85%A8%E7%90%83%E9%9B%BB%E5%AD%90%E5%9E%83%E5%9C%BE%E5%B4%97 (accessed on 24 June 2016).

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Guan, D. Take Responsibility for Electronic-Waste Disposal. Nature 2016, 536, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parties to the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. Basel Convention. Available online: http://www.basel.int/Countries/StatusofRatifications/PartiesSignatories/tabid/4499/Default.aspx#CN5 (accessed on 24 June 2016).

- Cap. 354 Waste Disposal Ordinance. Hong Kong E-Legislation. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap354!en-zh-Hant-HK?INDEX_CS=N (accessed on 24 June 2018).

- Klijn, E.H. Policy Networks: An Overview. In Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for Public Sector; Walter, J.M.K., Klijn, E.H., Koppenjan, J.F.M., Eds.; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 1997; pp. 14–34. ISBN 0761955488. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, M. Key Concepts in Governance; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2009; p. 156. ISBN 144620233X. [Google Scholar]

- Mizruchi, M.S.; Galaskiewicz, J. Networks of Internorganisational Relations. Sociol. Methods Res. 1993, 22, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, L. Policy Networks as Collective Action. Policy Stud. J. 2000, 28, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renckens, S. Yes, We Will! Voluntarism in US E-Waste Governance. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 2008, 17, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.P. Shared Responsibility for Managing Electronic Waste: A Case Study of Maine, USA. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 3014–3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisschop, L. How E-Waste Challenges Environmental Governance. In Hazardous Waste and Pollution; Wyatt, T., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, S.; Lau, K.; Zhang, C. Generation of and Control Measures for, E-Waste in Hong Kong. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Williams, E.; Ju, M.; Shao, C. Managing E-Waste in China: Policies, Pilot Projects and Alternative Approaches. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padiila, Y.C.; Daigle, L.E. Inter-Agency Collaboration in an International Setting. Adm. Soc. Work 1998, 22, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowing Who I Am and What I Know: Developing New Versions of Professional Knowledge in Integrated Service Settings. Available online: http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00001877.htm (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Hills, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Transboundary Pollution Between Guangdong Province and Hong Kong: Threats to Water Quality in the Pearl River Estuary and Their Implications for Environmental Policy and Planning. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 1998, 41, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- One Country, Two Systems, One Smog Cross-Boundary Air Pollution Policy Challenges for Hong Kong and Guangdong. Available online: https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/3-feature_2.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2018).

- Hills, P.; Roberts, P. Political Integration, Transboundary Pollution and Sustainability: Challenges for Environmental Policy in the Pearl River Delta Region. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2001, 44, 455–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Tackling Cross-Border Environmental Problems in Hong Kong: Initial Responses and Institutional Constraints. China Q. 2002, 172, 986–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scam Recycling: E-Dumping on Asia by US Recycler, the E-Trash Transparency Project, Basel Action Network. Available online: http://wiki.ban.org/images/1/12/ScamRecyclingReport-web.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2018).

- E-Waste in China: A Country Report. pp. 12, 14, 15, 17. Available online: https://collections.unu.edu/eserv/UNU:1624/ewaste-in-china.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Asian Network Workshop 2017 Updates on Waste Import and Export Control in Hong Kong SAR. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwixhfa175zeAhXBf7wKHUeaCbsQFjAAegQICRAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.env.go.jp%2Fen%2Frecycle%2Fasian_net%2FAnnual_Workshops%2F2017_PDF%2FS1_10_Hong_Kong_updated.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2dSqcrkQ0toRTzQ6l56fOg (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Recovery of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Recycling Programme. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/workplace/weee_intro.htm (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Shunichi, H.; Khetriwal, D.; Ruediger, K. Regional E-waste Monitor: East and Southeast Asia, 1st ed.; United Nations University and Japanese Ministry of the Environment: Tokyo, Japan, 2016; pp. 130, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Computer and Communication Products Recycling Programme. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/workplace/crp_intro.htm (accessed on 15 August 2018).

- Locations of Collection Point, Environmental Protection Department, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/quickaccess/vicinity.htm?collection_type=bin&material_type=all&district_id=0 (accessed on 5 July 2018).

- Report on the Development of Renewable Resources Recycling Industry 2018. Department of Circulation Industry Development, Ministry of Commerce of People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://ltfzs.mofcom.gov.cn/article/ztzzn/an/201806/20180602757116.shtml (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Eco Park, Hong Kong. Available online: www.Ecopark.com.hk (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- About EcoPark, EcoPark, Department of Environmental Protection. Available online: http://www.ecopark.com.hk/en/about.aspx (accessed on 3 July 2018).

- GEM Co. Ltd. Company Profile. Available online: http://en.gem.com.cn/index.php/gongsijianjie/ (accessed on 2 August 2018).

- Beijing Huanwei Company Profile. Available online: http://www.besg.com.cn/surroundings/CompanyProfile.html (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Hong Kong Blueprint for Sustainable Use of Resources 2013–2022, Environment Bureau. Available online: https://www.enb.gov.hk/sites/default/files/pdf/WastePlan-E.pdf (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Producers Responsibility Schemes. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/waste/pro_responsibility/index.html (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Control on Import & Export of Waste. Available online: https://www.epd.gov.hk/epd/english/environmentinhk/waste/guide_ref/guide_wiec_faq.html (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- The Hong Kong Collector/Recycler Directory. Available online: https://www.wastereduction.gov.hk/en/quickaccess/vicinity.htm?collection_type=collector&material_type=all&district_id=0 (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Category for Electrical and Electronic Waste, Pollution Control and Prevention. Available online: http://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzli/gtfwgl/dzdcplfqw/ (accessed on 12 August 2018).

- Detomasi, D.A. The multinational corporation and global governance: Modelling Global Public Policy Networks. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 71, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholders Involve in WEEE Governance in Hong Kong |

|---|

| Legislative Council |

| Environmental Protection Department |

| Private recyclers |

| Environmental groups |

| Hong Kong WEEE Recycling Association |

| Consumers |

| Customs |

| Legal Framework |

|

| |

| |

| Collection Mechanism |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Processing Infrastructure |

|

| |

| EHS Standards |

|

|

| Stakeholders Involve in WEEE Governance in the Mainland China |

|---|

| National Development and Reform Commission |

| Ministry of Ecology and Environment |

| Ministry of Commerce and Ministry of Finance |

| Customs |

| Environmental Groups |

| Informal recycling collectors |

| Legal Framework |

|

| Collection Mechanism |

|

| Processing Infrastructure |

|

| EHS Standard |

|

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wong, N.W.M. Electronic Waste Governance under “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong and Mainland China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112347

Wong NWM. Electronic Waste Governance under “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong and Mainland China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(11):2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112347

Chicago/Turabian StyleWong, Natalie W. M. 2018. "Electronic Waste Governance under “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong and Mainland China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 11: 2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112347

APA StyleWong, N. W. M. (2018). Electronic Waste Governance under “One Country, Two Systems”: Hong Kong and Mainland China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112347