The Dislike of Hot Thermal Conditions and Its Relationship with Sun (Ultraviolet Radiation) Exposure in the Southeastern United States

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Heat Perceptions and Preferences

2.2.2. Outside Preferences, the Non-Use of Sunburn Protective Measures and Tanning Habits

2.2.3. Demographic Variables

2.2.4. Climate and UVR of the Research Location

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

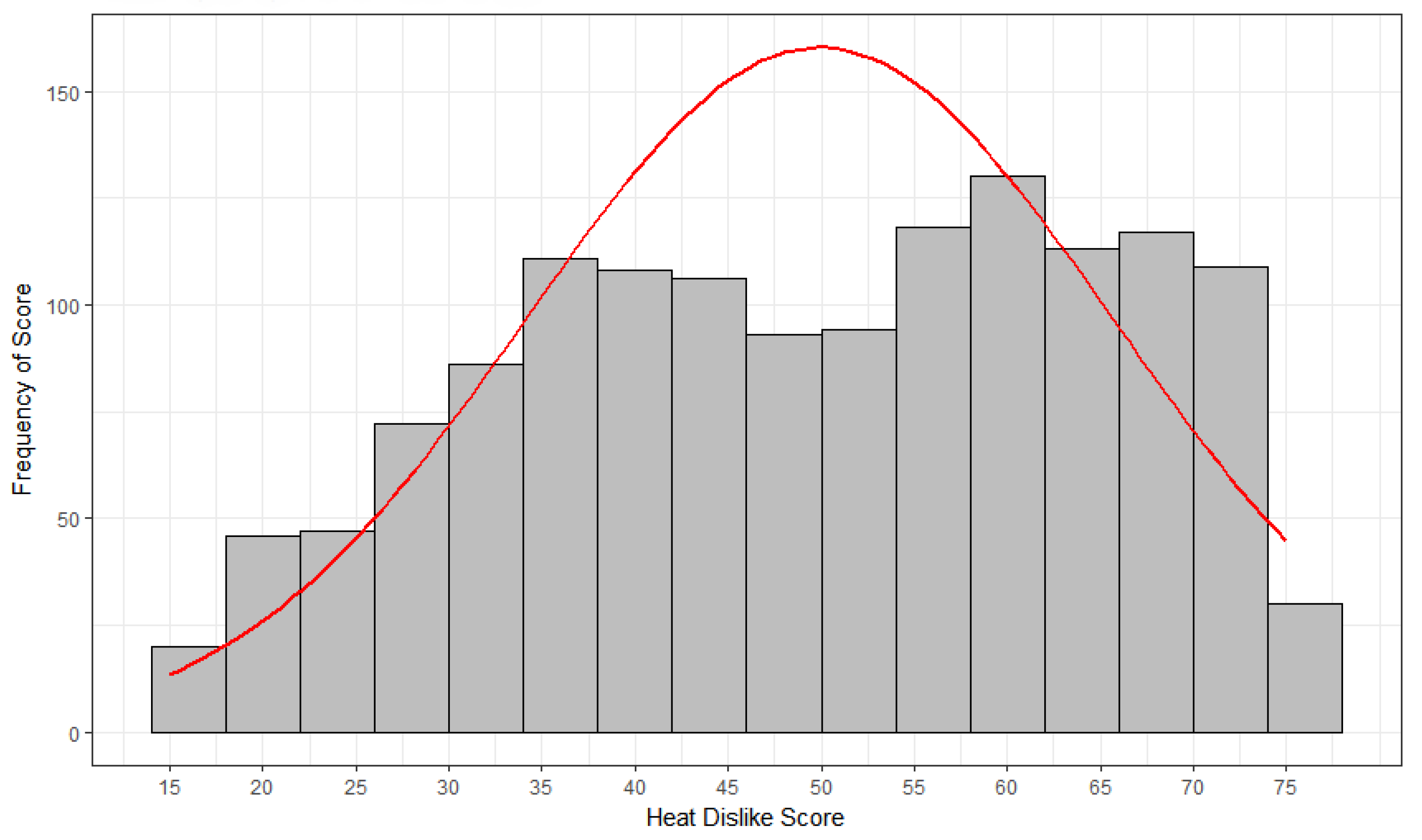

3.2. Individual Differences in Heat Perceptions and Preferences

3.3. Relationship of Heat Preferences and Sun Exposure Behaviors

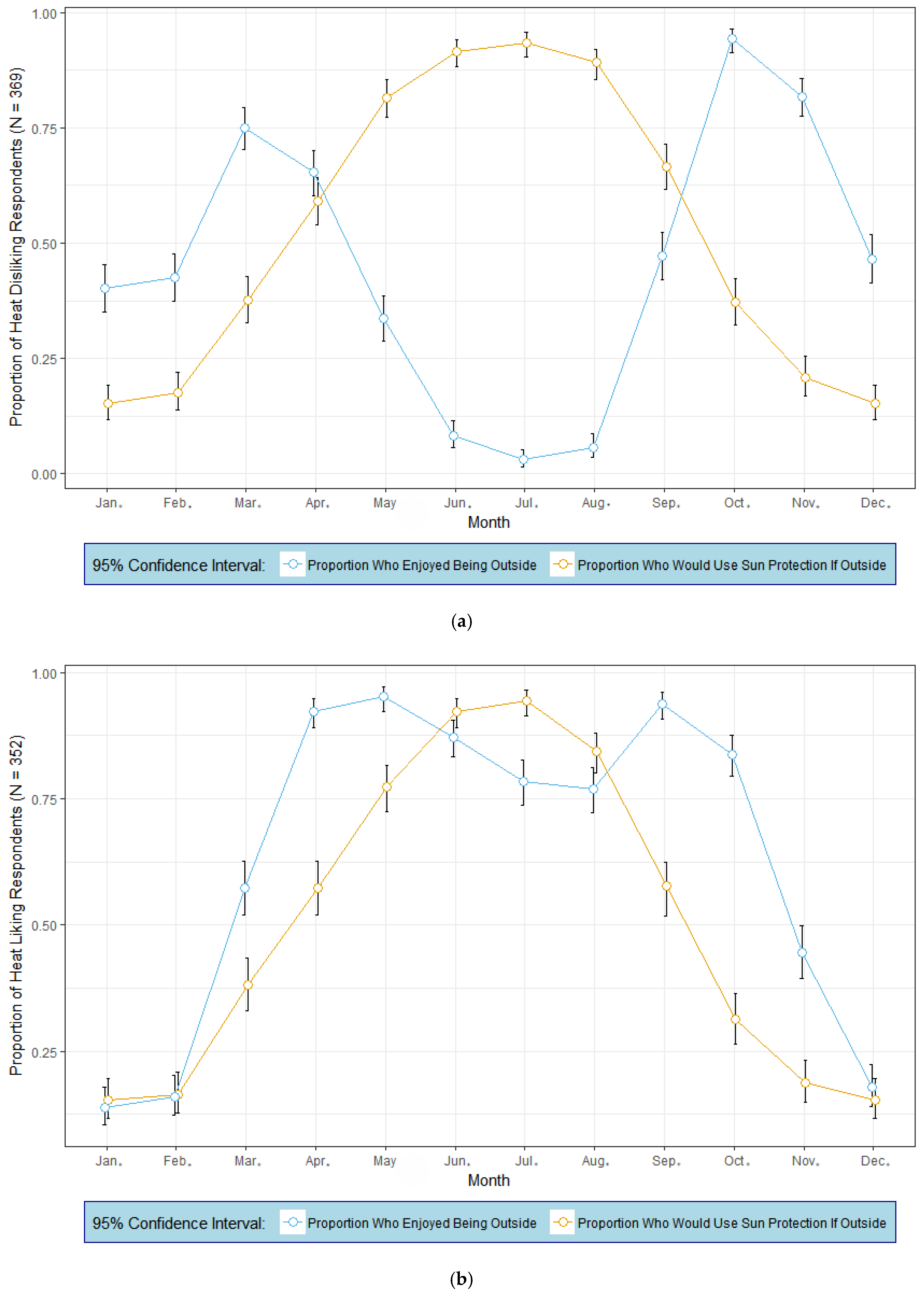

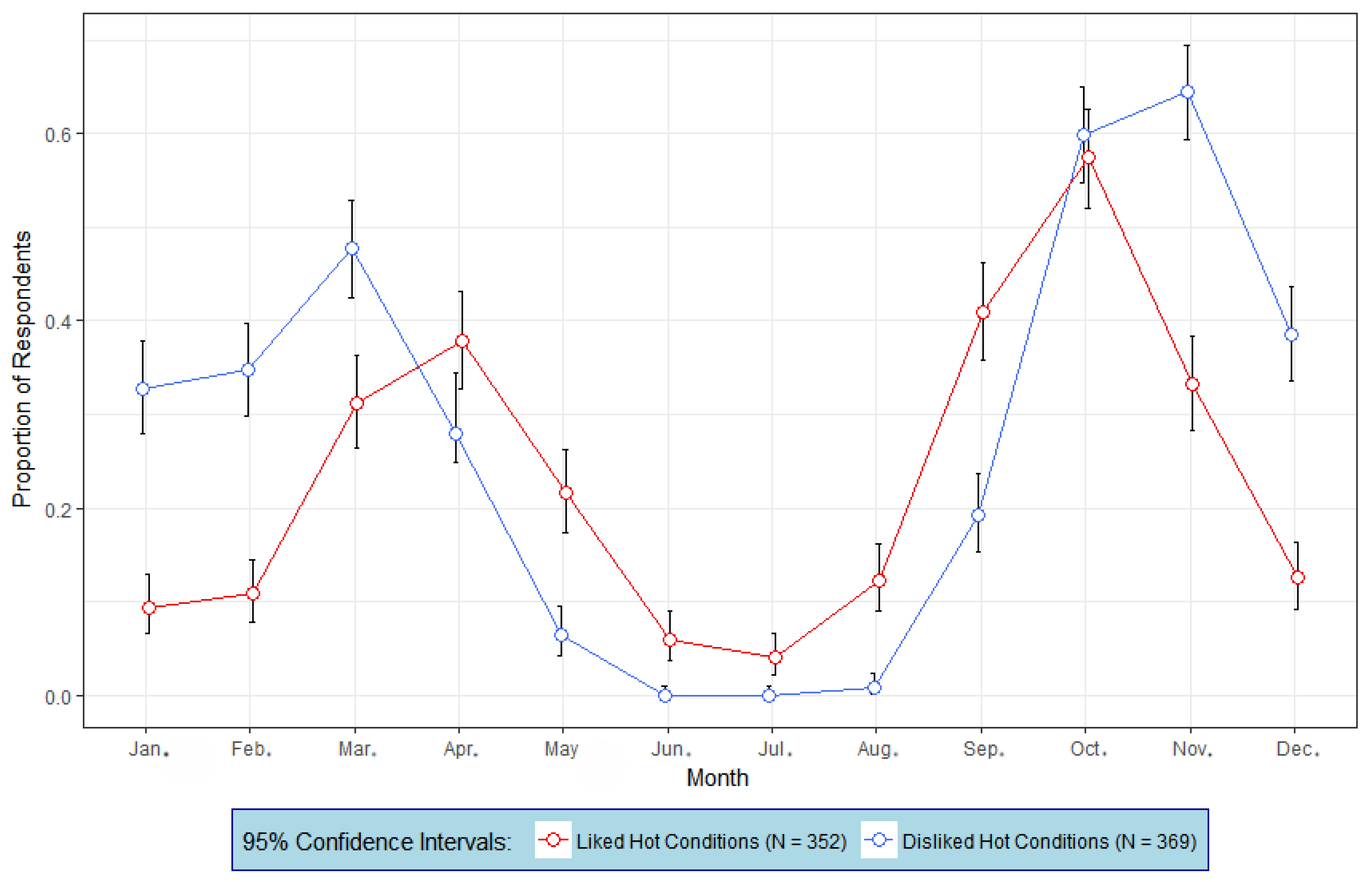

3.4. Relationship of Heat Preferences to Seasonal Outside Preferences and Use of Sunburn Protection

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United States Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer. Available online: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov (accessed on 7 May 2018).

- United States Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2014 Incidence and Mortality Web-Based Report. Available online: https://nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/ (accessed on 18 May 2018).

- Holman, D.M.; Freeman, M.B.; Shoemaker, M.L. Trends in melanoma incidence among non-hispanic whites in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 361–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimkhani, C.; Green, A.; Nijsten, T.; Weinstock, M.; Dellavalle, R.; Naghavi, M.; Fitzmaurice, C. The global burden of melanoma: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Br. J. Derm. 2017, 177, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, B.K.; Kricker, A. The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2001, 63, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, S.; Sera, F.; Cattaruzza, M.S.; Pasquini, P.; Picconi, O.; Boyle, P.; Melchi, C.F. Meta-analysis of risk factors for cutaneous melanoma: II. Sun exposure. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Barrett, J.H.; Bishop, D.T.; Armstrong, B.K.; Bataille, V.; Bergman, W.; Berwick, M.; Bracci, P.M.; Elwood, J.M.; Ernstoff, M.S.; et al. Sun exposure and melanoma risk at different latitudes: A pooled analysis of 5700 cases and 7216 controls. Int. J. Epidem. 2009, 38, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, A.C. The story behind the sharp decline in US tanning bed rates. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadalin, V.; Marrett, L.D.; Cawley, C.; Minaker, L.M.; Manske, S. Intentional tanning among adolescents in seven Canadian provinces: Provincial comparisons (CRAYS 2015). Prev. Med. 2018, 111, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Q.; Holman, D.M.; Jones, S.E.; Berkowitz, Z.; Guy, G.P. State indoor tanning laws and prevalence of indoor tanning among US high school students, 2009–2015. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimlin, M.G.; Lucas, R.M.; Harrison, S.L.; van der Mei, I.; Armstrong, B.K.; Whiteman, D.C.; Kricker, A.; Nowak, M.; Brodie, A.M.; Sun, J. The contributions of solar ultraviolet radiation exposure and other determinants to serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in Australian adults: The AusD Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014, 179, 864–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, N.J.; Parisi, A.V.; Igoe, D.P. Measurements of occupational ultraviolet exposure and the implications of timetabled yard duty for school teachers in Queensland, Australia: Preliminary results. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 131, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Lucas, R.M.; Harrison, S.; van der Mei, I.; Armgstrong, B.K.; Nowak, M.; Brodie, A.; Kimlin, M.G. The relationship between ambient ultraviolet radiation (UVR) and objectively measured personal UVR exposure dose is modified by season and latitude. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2014, 13, 1711–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, K. Human Thermal Environments, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morabito, M.; Grifoni, D.; Crisci, A.; Fibbi, L.; Orlandini, S.; Gensini, G.F.; Zipoli, G. Might outdoor heat stress be considered a proxy for the unperceivable effect of the ultraviolet-induced risk of erythema in Florence? J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2014, 130, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiala, D.; Havenith, G.; Bröde, P.; Kampmann, B.; Jendritzky, G. UTCI-Fiala multi-node model of human heat transfer and temperature regulation. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höppe, P. Aspects of human biometeorology in past, present, and future. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1997, 40, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auliciems, A. Towards a psycho-physiological model of thermal perception. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1981, 25, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Dear, R.J.; Brager, G.S. Developing an adaptive model of thermal comfort and preference. ASHRAE Trans. 1998, 104, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, I.; Thorsson, S. Influences of culture and environmental attitude on thermal emotional and perceptual evaluations of a public square. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2006, 50, 258–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Wong, N.H.; Jusuf, S.K. Thermal comfort in outdoor urban spaces in Singapore. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 426–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchaire, J.; Piette, A.; Kampmann, B.; Mehnert, P.; Gebhardt, H.; Havenith, G.; den Hartog, E.; Holmer, I.; Parsons, K.; Alfano, G.; et al. Development and validation of the predicted heat strain model. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2001, 45, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, A.M.; Murison, S.D.; Duncan, J.S.; Rance, K.A.; Speakman, J.R. Factors influencing variation in basal metabolic rate include fat-free mass, fat mass, age, and circulating thyroxine but not sex, circulating leptin, or triiodothyronine. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parsons, K.C.; Hamley, E.L. Practical methods for the estimation of human metabolic heat production. In Thermal Physiology; Mercer, J.B., Ed.; Excerpta Medica: Oxford, UK, 1985; pp. 777–781. [Google Scholar]

- Knez, I.; Thorsson, S.; Eliasson, I.; Lindberg, F. Psychological mechanisms in outdoor place and weather assessment: Towards a conceptual model. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, A.E. Minding the weather: The measurement of weather salience. Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 2009, 90, 1833–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated. Meteor Zeit. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Environmental Information. 2017 Local Climatological Data: Annual Summaries with Comparative Data—Athens, Georgia. Available online: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/IPS/lcd/lcd.html (accessed on 9 May 2018).

- World Health Organization; World Meteorological Organization; United Nations Environment Programme; International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection. Global Solar UV Index: A Practical Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.unenvironment.org/resources/report/global-solar-uv-index-practical-guide (accessed on 15 May 2018).

- Climate Prediction Center; National Center for Environmental Prediction. UV Index: Annual Time Series. Available online: http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/stratosphere/uv_index/uv_annual.shtml (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- UV-B Monitoring and Research Program. United States Department of Agriculture/Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado. Available online: http://uvb.nrel.colostate.edu/UVB/index.jsf (accessed on 7 September 2018).

- Maio, G.; Haddock, G. The Psychology of Attitudes and Attitude Change, 2nd ed.; Sage Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gershenwald, J.E.; Guy, G.P. Stemming the rising incidence of melanoma: Calling prevention to action. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2016, 108, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; Murzaku, E.C.; Penn, L.; Abbasi, N.R.; Davis, P.D.; Berwick, M.; Polsky, D. More skin, more sun, more tan, more melanoma. Am. J. Public Health 2014, 104, e92–e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Climate Variable | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | |

| Average Maximum Temperature (°C) | 11.8 | 13.5 | 18.3 | 23.1 | 27.3 | 30.7 | 32.3 | 31.7 | 28.3 | 23.3 | 17.6 | 12.8 |

| Average Minimum Temperature (°C) | 0.7 | 1.7 | 5.6 | 9.7 | 14.5 | 18.7 | 20.8 | 20.4 | 17.1 | 10.7 | 5.2 | 1.8 |

| Average Daily Temperature (°C) | 6.3 | 7.6 | 11.9 | 16.4 | 20.9 | 24.8 | 26.6 | 26.1 | 22.7 | 17.0 | 11.4 | 7.3 |

| Average Daily Relative Humidity (%) | 69 | 65 | 64 | 63 | 69 | 72 | 74 | 76 | 75 | 73 | 71 | 70 |

| Average Percentage of Possible Sunshine | 49 | 54 | 58 | 66 | 68 | 67 | 63 | 75 | 64 | 63 | 58 | 50 |

| Average Number of Days with Clear Skies | 8.7 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 8 | 9.5 | 13.3 | 11.5 | 9.4 |

| Average Number of Days with Partly Cloudy Skies | 6.9 | 6.3 | 7.4 | 8.4 | 10.5 | 11.8 | 12.8 | 12.5 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 6 |

| UV Index Category | Month | Year (%) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sept. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | ||

| Low (UVI = 0 to 3) | 1.5 (5.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.04 (0.2) | 3.3 (11.5) | (1.4) |

| Moderate (UVI = 3 to 5) | 29.1 (94.8) | 23.4 (85.0) | 3.6 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13.1 (42.6) | 29.6 (99.8) | 25.5 (88.5) | (35.1) |

| High (UVI = 6 to 7) | 0 (0) | 4.1 (14.8) | 18.1 (60.0) | 3.4 (11.7) | 0.2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.9 (20.6) | 17.3 (56.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (13.8) |

| Very High (UVI = 8 to 10) | 0 (0) | 0.04 (0.2) | 8.4 (28.0) | 24.1 (82.0) | 22.1 (72.8) | 9.7 (33.2) | 7.5 (25.3) | 22.5 (76.0) | 22.7 (78.9) | 0.3 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (33.1) |

| Extreme (UVI > 10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (6.4) | 8.1 (26.6) | 19.6 (66.8) | 22.2 (74.7) | 7.1 (24.0) | 0.13 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | (16.4) |

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 430 | 30.7 |

| Female | 970 | 69.3 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 86 | 6.2 |

| Asian American | 114 | 8.2 |

| Caucasian American | 1034 | 74.0 |

| Hispanic American | 49 | 3.5 |

| Other | 115 | 8.2 |

| Any attempt to suntan this season? | ||

| Yes | 685 | 48.9 |

| No | 715 | 51.1 |

| Reaction of skin when outside for one hour in the middle of the day for the first time in summer without sunscreen | ||

| Burn then peel | 388 | 27.7 |

| Burn then tan | 561 | 40.1 |

| Tan only | 451 | 32.2 |

| To what extend do you like to get a suntan? | ||

| Do not like getting a suntan at all | 295 | 21.1 |

| Like getting a suntan very little | 231 | 16.5 |

| Somewhat like getting a suntan | 355 | 25.4 |

| Like getting a suntan | 319 | 22.8 |

| Very much like getting a suntan | 200 | 14.3 |

| Typical sun exposure behavior when strong summer sunlight is available in a tropical location | ||

| Sun bathe several hours each day | 182 | 13.0 |

| Casual sun exposure only | 476 | 34.0 |

| Use sun protection | 670 | 47.9 |

| Avoid the sun at all times | 72 | 5.1 |

| Level of tan at the end of summer or after a holiday that involves sun exposure | ||

| A dark tan | 638 | 45.6 |

| A medium tan | 531 | 37.9 |

| A light tan | 198 | 14.1 |

| Practically no tan | 33 | 2.4 |

| Ever use a tanning salon? | ||

| Yes | 313 | 22.4 |

| No | 1087 | 77.6 |

| Use of a tanning salon this season | ||

| Yes | 96 | 30.8 |

| No | 216 | 69.2 |

| Typical Sun Exposure Behavior | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun bathe several hours each day | 182 | 41.1 | 14.6 |

| Casual sun exposure only * | 476 | 49.5 | 14.9 |

| Use sun protection * | 670 | 50.9 | 15.5 |

| Avoid the sun at all times | 72 | 65.3 | 9.9 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stewart, A.E.; Kimlin, M.G. The Dislike of Hot Thermal Conditions and Its Relationship with Sun (Ultraviolet Radiation) Exposure in the Southeastern United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102161

Stewart AE, Kimlin MG. The Dislike of Hot Thermal Conditions and Its Relationship with Sun (Ultraviolet Radiation) Exposure in the Southeastern United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018; 15(10):2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102161

Chicago/Turabian StyleStewart, Alan E., and Michael G. Kimlin. 2018. "The Dislike of Hot Thermal Conditions and Its Relationship with Sun (Ultraviolet Radiation) Exposure in the Southeastern United States" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15, no. 10: 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102161

APA StyleStewart, A. E., & Kimlin, M. G. (2018). The Dislike of Hot Thermal Conditions and Its Relationship with Sun (Ultraviolet Radiation) Exposure in the Southeastern United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(10), 2161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102161