I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Construction of Dog Needs

3.1.1. A Fundamental Need for Exercise

“The best way to put it is, see him as yourself and if you get fat you don’t like it and he won’t like it. Maybe he’ll go on a downer, I don’t know, but I’m trying to keep him fit and healthy and treat him like I am myself (…), I try and put myself in his shoes and if it’s something which clearly I don’t like, for instance trapped in four walls all day, that’s torture and I can’t see that being a nice thing.”—Adam

“Because they need to be fit, they can’t just be lumpy in fatness and they can’t laze around because it wouldn’t be good for them.”—Child

“If you’ve got a strong relationship with your dog you want to do what’s best for them.”—Mary

“He gets lots of exercise, a minimum of 2 hours a day. He gets nice food. Well, he’s never complained (laughter). Yeah he is treated well, he’s not mistreated, he’s NEVER been hit. (…) I think he has got a good life.”—Charles

3.1.2. Normative Guidelines on Dog Walking

“Well, the size of a dog, take your (BLINDED) (Pug X). The amount of steps that she’s got to take per metre have got to be far greater than what Ralph (Alaskan Malamute) does. So I wouldn’t expect her to need as much exercise as him”.—Charles

“I do accept different breeds need different things. I do know that because I know actually the really big breeds and even like the likes of Whippets don’t actually need that much, do they. Again, very small ones. I think your medium size and your working dogs are the worst for needing (…) it’s breed and temperament, isn’t it. I know I’ve got a dog that has high needs, I do know that and all the stuff on (breed) say that.”—Diane

3.1.3. Enculturation

“I felt guilty about not taking them for a walk, but then I’d kind of look at them and go, “They don’t seem bothered by it. They’re chilling out, they’re not barking, they’re not bugging us for attention, they’re not chewing.”—Nadine

3.1.4. Dog Behaviour as a Motivator

“Her tail’s up. Her ears are up. She looks like she’s having a great time. It makes you think that.”—Emily

“I would say if you want to do the right thing for your dog, make your dog happy, then take it for a walk, make it all nice and happy.”—Child

“He lets me know. If it’s raining, we’ll walk half way down the main path there like that and he’ll just stop and look at me to say, “…this is stupid this. Let’s get back in the car and go.” (Laughter), but he’ll just turn round and he’ll just trot up to the car.”—Harold

“He was the main reason why we started to realise that dogs don’t always need to be walked every day. For him, it was too stressful, to go on a walk every day”—Nadine

“It is partly led by him, it really is. I know he is not a lap dog, he’s a working dog. He demands it and you would have seen he’s demanding me to walk in a way that I never saw (Name’s) dog do. But at the end of the day what came first? It’s one of those. Does he demand because he expects and he gets, or do I give him it and he gets it because he’s demanding it?”—Diane

3.2. Dog Outcomes

3.3. Owner Needs—the Issue of Capacity

3.3.1. Health

3.3.2. Time

“Erm.....health, is the only excuse that I can give for people not walking their dogs. I think everything else is an excuse. Beyond that. People that say that they don’t have time to walk a dog, shouldn’t have a dog. Personal opinion. (…) My dog doesn’t need it. My dog doesn’t like going out in the wet. My dog’s lazy. No it’s not, you are.”—Alice

3.3.3. Routines and Co-Discipline

3.4. Owner Outcomes

3.4.1. Owner Happiness

“With my job being quite stressful at times it is relaxing. It might not seem it when I am getting them in and out the van but when I’m actually out there and I am by myself with just the dogs it is my chill time. I’ve got to do it every day for my sanity let alone theirs”—Samantha

“It just feels special when they’re there with you. It makes a good walk an excellent walk. It’s that little bit more when you’ve got an animal by the side of you.”—Mary

“It’s not just about the physical activity they give you, it’s the mental benefits. My friend who doesn’t have her own dog comes walking with us and says that it’s impossible to leave depressed after watching the dogs running around enjoying themselves.”—Excerpt from conversation recorded in ethnographic diary.

“I thoroughly enjoy it because I think he enjoys it and I love the thought of him being happy, so to know that he is out somewhere new and he is enjoying himself and that he’s allowed to sniff and he is bouncing around and you can tell that he is excited, I love that.”—Nina

3.4.2. Owner Exercise

“Mitch: Just to make sure that he’s healthy, his mind is... That he is doing dog things, I suppose, when he’s getting out. That’s about it. It’s nice for us to get out and exercise as well.Interviewer: Yes. Was that part of the consideration when you got Ozzie?Mitch: It wasn’t actually, no, but it’s just a benefit of having a dog, I suppose.”

3.4.3. Connectedness

“We don’t get much time for us; it’s quite nice me time so, even though I’m out with the dog and we’re doing whatever, it’s nice to be alone with your thoughts, just to sort of relax and think more than anything else. So when someone else’s dog comes up and bursts your bubble, (Laughter) it literally goes pop and the whole world comes down; it’s like, “Oh for God’s sake.”—Jake

“…one thing lives off another and it gets better”—Barry

“I feel like I can compensate and if you like I still maintain that relationship with him. I don’t feel like he loves me for the fact that I take him for a walk, although seeing him with mum I know that it’s a big influence and factor that he does. I think he just adores her and I love that, I love it, but my relationship with him I don’t think is based on walks (…) I think for me I just smother him in love physically and emotionally and that’s how we maintain our relationship.”—Nina

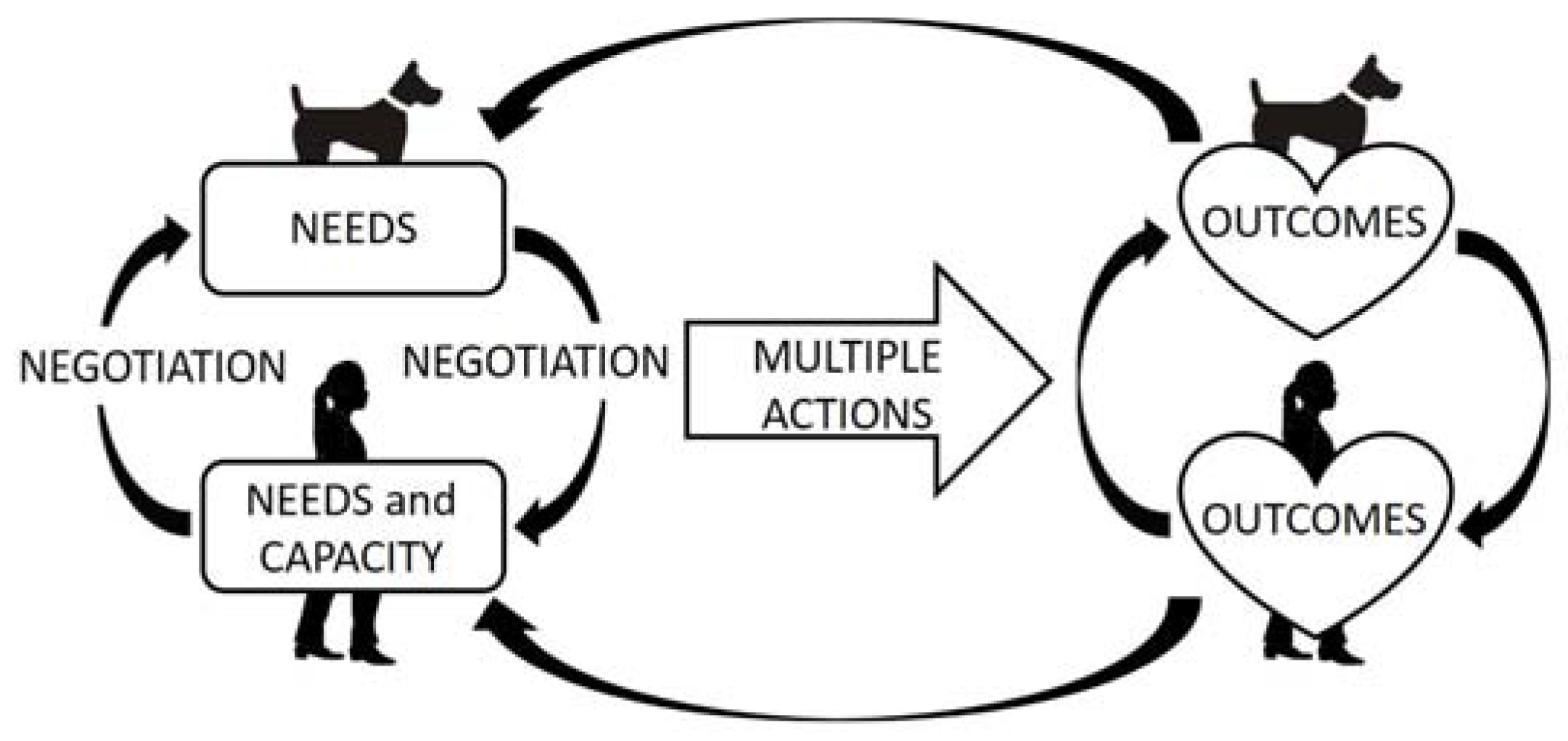

3.5. Negotiating Needs

“I was working from home and the day flew by, and it was early afternoon and I still hadn’t had time to take the dogs out. I found myself thinking about someone I had recently interviewed and how they justified giving the dogs a bit of play time instead of a walk, if they don’t have time to take them out. So I took (BLINDED) out in the garden and played fetch for a few minutes. (BLINDED) looked tired out so I let her sleep. I thought “she’s getting old now and will be ok without a walk today, I will give her a rest”. (…)As I was throwing the ball again for (BLINDED) in the garden I suddenly thought WHAT AM I DOING! It was like a wake-up moment....I really shouldn’t not walk them. This project makes me feel hugely guilty when I notice myself constructing justifications as to why I don’t need to walk them, because it fits with my own needs that day.So I put their leads on and took them out. Sod work.Although we only went around the block. Better than nothing but I was really running late!”—Ethnographic diary

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Interview Schedule

- Type

- Where did you get it?

- Why did you get it?

- Personality—what are your dog’s favourite things?

- What do you feed your dog?—main diet, treats

- Relationship with dog(s)

- ○

- What do you like about owning a dog?

- ○

- Does owning a dog ever cause problems or difficulties?

- ○

- What are the most/least enjoyable parts of owning a dog?

- ○

- How would you describe your relationship with your dog?

- ○

- Does your dog live outside or inside?

- ○

- Who owns the dog?

- ○

- Who is responsible for dog duties such as feeding, grooming, exercise?

- ○

- Would you consider your dog to be part of the family?

- Going out with the dog(s)

- ○

- Can you describe a typical dog walk?

- ▪

- Who does it?

- ▪

- When, how often?

- ▪

- Where?

- ▪

- What happens?—activity types

- ▪

- Do you walk your dog on or off lead?

- ▪

- How does your dog typically behave?

- ▪

- How do you feel when you are walking your dog?

- ▪

- What do you think about whilst walking your dog?

- ○

- How close do you live to walking areas and what are they like?

- ▪

- How suitable are they for dog walking?

- ▪

- Which walking areas do you use (distance over suitability?). What do you look for when choosing a place to walk your dog?

- ▪

- In the past where you have lived how close were you to dog walking areas compared to now? Do you think this had an effect on your dog walking when you moved house?

- ○

- Do you see any other people when walking your dog?

- ▪

- Can you tell me some more about the kinds of conversations you have with other people when you out walking with your dog? (Do they involve anything more than just a “Hi”?)

- ▪

- Do you ever meet up with other people to go for a walk?

- ○

- What do you look forward to about walking your dog?

- ○

- What things don’t you look forward to about walking your dog?

- ○

- Do you ever have any problems or issues when out for a walk with your dog(s)?

- ○

- Can you describe any solutions to these problems that you use? Management strategies?

- ○

- What sorts of things stop you from going for a walk with your dog/s?

- ○

- Tell me about a time you were unable to take your dog for a walk—what happened, why did it happen?

- ○

- Do you do other physical activities? How do you decide whether to walk the dogs or do other activities?

- ○

- Can you describe things that you feel are motivators to walking your dog?

- ○

- Can you describe any barriers to walking with your dog?

- ○

- Is it much different going for a walk with a dog compared to a friend?

- ○

- What sorts of benefits, if any, do you see to walking WITH your dog? As opposed to walking on your own.

- ○

- You have explained a lot about your relationship with your dog, and about walking your dog—could you reflect on whether you think these two things are linked?

- Personal beliefs/values about dog ownership/walking

- ○

- What do you think might prevent or make it difficult for other dog owners to walk their dogs.

- ○

- If you had a friend and you wanted to encourage them to start walking their dogs, or walking with you and your dog, what would you tell them?

- ○

- How important do you think exercise is for dogs? How often do they need walking?

- ▪

- Where do you think this opinion comes from? Why do you believe that?

- ○

- Breed of dog—how much exercise does this breed need? Does that influence how you walk your dog?

- ○

- Are you think kind of person who finds it difficult or easy to get things done? How disciplined are you?

- Significant others—subjective norms—explore views of people mentioned in above (i.e., does your partner feel the same, other family members? What does your vet think?—interjections as required from above)

- ○

- Who would you seek advice from about dogs? Whose opinion do you value when it comes to dogs?

- ○

- Do any of your friends have dogs? Family?

References

- Bull, F.C. Physical Activity Guidelines in the UK: Review and Recommendations; Loughborough University: Loughborough, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paluska, S.A.; Schwenk, T.L. Physical activity and mental health. Sport Med. 2000, 29, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawe, P.; Shiell, A. Social capital and health promotion: A review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 51, 871–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England, N. Monitor of Engagement with the Natural Environment: The National Survey on People and the Natural Environment—Annual Report from the 2011–12 Survey (NECR094). Available online: http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/1712385 (accessed on 21 April 2017).

- Christian, H.; Bauman, A.; Epping, J.N.; Levine, G.N.; McCormack, G.; Rhodes, R.E.; Richards, E.; Rock, M.; Westgarth, C. Encouraging dog walking for health promotion and disease prevention. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, G.N.; Allen, K.; Braun, L.T.; Christian, H.E.; Friedmann, E.; Taubert, K.A.; Thomas, S.A.; Wells, D.L.; Lange, R.A.; American Heart Association Council; et al. Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013, 127, 2353–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNicholas, J.; Collis, G.M. Dogs as catalysts for social interactions: Robustness of the effect. Br. J. Psychol. 2000, 91, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messent, P.R. Social facilitation of contact with other people by pet dogs. In New Perspectives on Our Lives with Companion Animals; Katcher, A.H., Beck, A.M., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1983; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, L.; Giles-Corti, B.; Bulsara, M.; Bosch, D. More than a furry companion: The ripple effect of companion animals on neighborhood interactions and sense of community. Soc. Anim. 2007, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courcier, E.A.; Thomson, R.M.; Mellor, D.J.; Yam, P.S. An epidemiological study of environmental factors associated with canine obesity. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 51, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, H.; Westgarth, C.; Bauman, A.; Richards, E.A.; Rhodes, R.; Evenson, K.; Mayer, J.A.; Thorpe, R.J. Dog ownership and physical activity: A review of the evidence. J. Phys. Act. Health 2013, 10, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, V.; Rhodes, R.; Higgins, J.W. Unleashing physical activity: An observational study of park use, dog walking, and physical activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, 766–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobster, P.H. Recreation and leisure research from an active living perspective: Taking a second look at urban trail use data. Leisure Sci. 2005, 27, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Rhodes, R.E. Sizing up physical activity: The relationships between dog characteristics, dog owners’ motivations, and dog walking. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2016, 24, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkie, R. Multispecies scholarship and encounters: Changing assumptions at the human-animal nexus. Sociology 2015, 49, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Christian, H.E. How might we increase physical activity through dog walking? A comprehensive review of dog walking correlates. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activ. 2014, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, K.; Shibata, A. Prevalence and correlates of dog walking among Japanese dog owners. J. Phys. Act. Health 2012, 9, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgarth, C.; Boddy, L.M.; Stratton, G.; German, A.J.; Gaskell, R.M.; Coyne, K.P.; Bundred, P.; McCune, S.; Dawson, S. A cross-sectional study of frequency and factors associated with dog walking in 9–10 year old children in Liverpool, UK. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, H.; Giles-Corti, B.; Knuiman, M. “I’m just a’-walking the dog” correlates of regular dog walking. Family Community Health 2010, 33, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.G.; Rhodes, R.E. Relationships among dog ownership and leisure-time walking in western Canadian adults. Amer. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoerster, K.D.; Mayer, J.A.; Sallis, J.F.; Pizzi, N.; Talley, S.; Pichon, L.C.; Butler, D.A. Dog walking: Its association with physical activity guideline adherence and its correlates. Prev. Med. 2011, 52, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westgarth, C.; Knuiman, M.; Christian, H.E. Understanding how dogs encourage and motivate walking: Cross-sectional findings from reside. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degeling, C.; Rock, M. It was not just a walking experience: Reflections on the role of care in dog-walking. Health Promot. Int. 2013, 28, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.A.; Meadows, R.L. Dog-walking: Motivation for adherence to a walking program. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2010, 19, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohlf, V.I.; Bennett, P.C.; Toukhsati, S.; Coleman, G. Beliefs underlying dog owners’ health care behaviors: Results from a large, self-selected, internet sample. Anthrozoos 2012, 25, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Murray, H.; Temple, V.A.; Tuokko, H.; Higgins, J.W. Pilot study of a dog walking randomized intervention: Effects of a focus on canine exercise. Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickup, E.; German, A.J.; Blackwell, E.; Evans, M.; Westgarth, C. Variation in activity levels amongst dogs of different breeds: Results of a large online survey of dog owners from the UK. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, C.; Mays, N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: An introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. Brit. Med. J. 1995, 311, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, T.M.; Glover, T.D. On the fence: Dog parks in the (un)leashing of community and social capital. Leisure Sci. 2014, 36, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B. A review and analysis of the use of “habit” in understanding, predicting and influencing health-related behaviour. Health Psychol. Rev. 2014, 9, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, R.E.; Lim, C. Understanding action control of daily walking behavior among dog owners: A community survey. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, K.; Smith, C.M.; Tumilty, S.; Cameron, C.; Treharne, G.J. How does dog-walking influence perceptions of health and wellbeing in healthy adults? A qualitative dog-walk-along study. Anthrozoös 2016, 29, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T.; Platt, L. (Just) a walk with the dog? Animal geographies and negotiating walking spaces. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, E.; Douglas, M.; Parry, O.; Lawton, J. Type 2 diabetes and dog walking: Patients’ longitudinal perspectives about implementing and sustaining physical activity. Brit. J. Gen. Pract. 2010, 60, 570–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robins, D.M.; Sanders, C.R.; Cahill, S.E. Dogs and their people: Pet-facilitated interaction in a public setting. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1991, 20, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, C.; Rock, M.; Rogers, W.; Riley, T. Habitus and responsible dog-ownership: Reconsidering the health promotion implications of “dog-shaped” holes in people’s lives. Crit. Public Health 2016, 26, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okun, M.A.; Ruehlman, L.; Karoly, P.; Lutz, R.; Fairholme, C.; Schaub, R. Social support and social norms: Do both contribute to predicting leisure-time exercise? Am. J. Health Behav. 2003, 27, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, G.; Cheng, L.A.; Mélo, E.N.; de Farias Júnior, J.C. Physical activity and social support in adolescents: A systematic review. Health Educ. Res. 2014, 29, 822–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trost, S.G.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.E.; Sallis, J.F.; Brown, W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2002, 34, 1996–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, C. The everyday dog owner. In Understanding Dogs: Living and Working with Canine Companions; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 16–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hearne, V. Animal Happiness; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, D. 1: An introduction in three parts. In Playing with My Dog Katie; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 2007; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J. 6: Working it out. In Family Obligations and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Cutt, H.E.; Giles-Corti, B.; Wood, L.J.; Knuiman, M.W.; Burke, V. Barriers and motivators for owners walking their dog: Results from qualitative research. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2008, 19, 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J. 1: Support between kin: Who give what to whom? In Family Obligations and Social Change; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- Prato-Previde, E.; Fallani, G.; Valsecchi, P. Gender differences in owners interacting with pet dogs: An observational study. Ethology 2006, 112, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.; Reilly, J.J.; Penpraze, V.; Westgarth, C.; Ward, D.S.; Mutrie, N.; Hutchison, P.; Young, D.; McNicol, L.; Calvert, M.; et al. Children, parents and pets exercising together (CPET): Exploratory randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, M.P.; Barker, M. Why is changing health-related behaviour so difficult? Public Health 2016, 136, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, K.L.; Murphy, D.; Ferrara, C.; Oleski, J.; Panza, E.; Savage, C.; Gada, K.; Bozzella, B.; Olendzki, E.; Kern, D.; et al. An online social network to increase walking in dog owners: A randomized trial. Med. Sci. Sports Exercise 2015, 47, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.; Edwards, V. In the company of wolves—The physical, social, and psychological benefits of dog ownership. J. Aging Health 2008, 20, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.W.; Temple, V.; Murray, H.; Kumm, E.; Rhodes, R. Walking sole mates: Dogs motivating, enabling and supporting guardians’ physical activity. Anthrozoos 2013, 26, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheibeck, R.; Pallauf, M.; Stellwag, C.; Seeberger, B. Elderly people in many respects benefit from interaction with dogs. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2011, 16, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, P. Situated activities in a dog park: Identity and conflict in human-animal space. Soc. Anim. 2012, 20, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurier, E.; Maze, R.; Lundin, J. Putting the dog back in the park: Animal and human mind-in-action. Mind Culture Activity 2006, 13, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Interview Type | Gender(s) | Ethnicity(s) | Age(s) | Occupation(s) | Dog(s) | Frequency Dog Walked | Walk Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full | F | White | 51 | Associate professional and technical | MN Poodle/spaniel 10 years, FN Border Terrier 10 years | Twice daily | No |

| Full | M | Mixed | 62 | Retired | MN Alaskan Malamute 5 years | Twice daily | Yes |

| F not present | White | 49 | Skilled trade | ||||

| Full | M | White | 69 | Retired | ME Labrador 4 years | Twice daily | Yes |

| F not present | Unknown | Unknown | Retired | ||||

| Full | F | White | 36 | Student | ME Spanish Water Dog | Three times daily | Yes |

| Child M | 2 | Child | |||||

| Full | F | White | 42 | Associate professional and technical Associate professional and technical children | FN Border collie/Springer spaniel | Once–twice daily | Yes |

| M | 45 | ||||||

| Child M | 10 | ||||||

| Child F | 5 | ||||||

| Full | F | White | 38 | Professional | FN Labrador 9 years, ME French Bulldog 1 year, FE French Bulldog 8months | Once–twice daily | Yes |

| Adult M not present | 52 | Manager | |||||

| Child F | 9 | Children | |||||

| Child M | 7 | ||||||

| Full | F | White | 68 | Retired | MN Border Collie 12 years, ME Border Collie 7 years | Never | No |

| Full | F | White | 58 | Manager | MN Cavalier King Charles Spaniel 3 years, plus regular visiting MN Cavalier King Charles Spaniel | Daily | Yes |

| M part-present | 56 | Manager | |||||

| F | 28 | Professional | |||||

| Full | F | White | 52 | Permanently sick or disabled | MN Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retriever 14 years | Several times a month | No |

| Full | F | White | 29 | Professional | MN Husky/Malamute 7 years, FN Labrador 4 years | Several times a week | Yes |

| M | 29 | Professional | |||||

| Child M | 2 | Child | |||||

| Full | F | White | 63 | Retired | MN Old English Sheepdog 9 years, MN Old English Sheepdog 7 years | Once–twice daily, short lead walk | Yes |

| M | 68 | Retired | |||||

| Full | M | White | 40 | Manager | FN Jack Russell 7 years, MN Cocker Spaniel 4 years | Daily | Yes |

| F | 44 | Manager | |||||

| Mini-dog show | M | White | Adult | Unknown | Four Old English Sheepdogs | Twice daily | No |

| Mini-dog show | M | White | Adult | Unknown | Afghan Hounds | Intermittently | No |

| Mini-dog show | F | White | Adult | Professional | Eight foxhounds and two Border Collies | Daily | No |

| Mini-dog show | M | White | Adult | Unknown | Pyrenean Mountain Dog | Daily | No |

| Mini-park | M | White-Asian | Adult | Unknown | M Jack Russell 10months | Daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | M | White | Adult | Unknown | F Staffordshire bull terrier, unknown age | Three times daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | M | White European | Adult | Elementary | M American Staffordshire Bull Terrier *, M American Staffordshire Bull Terrier */Labrador | At least daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-street | M | White | Elderly | Retired | M Labrador 13 years | Daily, short lead walk | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | M | White | Young adults | Unknown | M Pug 6months | Daily | Met on a walk |

| F | |||||||

| Mini-park | F | White | Adults and children | Unknown | F Chihuahua 5 months | Daily | Met on a walk |

| M | |||||||

| plus 3 children playing | |||||||

| Mini-park | M | White | Adult | Unknown | M Rottweiler, F other dog | Daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | M | White | Adult | Unknown | M Jack Russell Terrier/Yorkshire Terrier 13 years | Daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | F | White | Adult | Unknown | M Jack Russel 4 years, F Jack Russell 3years | Three times daily | Met on a walk |

| Mini-park | M | White | Adult | Unknown | M King Charles Spaniel | Twice–three times daily | Met on a walk |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Westgarth, C.; Christley, R.M.; Marvin, G.; Perkins, E. I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080936

Westgarth C, Christley RM, Marvin G, Perkins E. I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(8):936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080936

Chicago/Turabian StyleWestgarth, Carri, Robert M. Christley, Garry Marvin, and Elizabeth Perkins. 2017. "I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 8: 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080936

APA StyleWestgarth, C., Christley, R. M., Marvin, G., & Perkins, E. (2017). I Walk My Dog Because It Makes Me Happy: A Qualitative Study to Understand Why Dogs Motivate Walking and Improved Health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(8), 936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14080936