What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Risky Play | ||

| Risky Play Categories [5,6] | Definition | Examples |

| Great heights | Danger of injury from falling | Climbing/jumping from surfaces, balancing/playing on high objects (e.g., playground equipment), hanging/swinging at great heights |

| High speed | Uncontrolled speed and pace that can lead to collision with something (or someone) | Swinging at high speed |

| Dangerous tools | Can lead to injuries and wounds | Cutting tools (e.g., knives, saws, or axes), strangling tools (e.g., ropes) |

| Dangerous elements | Where children can fall into or from something | Cliffs, water, fire pits, trees |

| Rough and Tumble Play | Where children can be harmed | Wrestling or play fighting with other children or parents |

| Disappear/get lost | Where children can disappear from the supervision of adults or get lost alone | Exploring alone, playing alone in unfamiliar environments, general independent mobility, or unsupervised play |

1.1. Playground Safety Standards

1.2. Adult Supervision

1.3. Influence of Injury Prevention on Risky Outdoor Play and Injury Rates

1.4. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health?

2. Methods

2.1. Study Inclusion Criteria

| Risky Play Environment Environment that affords or accommodates risky play behaviours [69]. | ||

| Affordances Features of the environment can enable and invite children to engage in certain types of play behaviours [70]. Affordances are unique for each individual and can be influenced by personal characteristics (e.g., strength, fear) and other features that may inspire or constrain actions (e.g., trees with low branches afford climbing). | ||

| Risky Play Environments | Affordances for Risky Play | Risky Play Category |

| Climbable features [69] | Affords climbing | Great heights |

| Jump down-off-able features [69] | Affords jumping down | Great heights |

| Balance-on-able features [69] | Affords balancing | Great heights |

| Flat, relatively smooth surfaces [69] | Affords running, RTP | High speed, RTP |

| Slopes and slides [69] | Affords sliding, running | High speed |

| Swing-on-able features [69] | Affords swinging | High speed, great heights |

| Graspable/detached objects [69] | Affords throwing, striking, and fencing | RTP |

| Dangerous tools [69] | Affords whittling, sawing, axing, and tying | Dangerous tools |

| Dangerous elements close to where the children play (e.g., lake/pond/sea, cliffs, fire pits, etc.) [69] | Affords falling into or from something | Dangerous elements |

| Enclosure/restrictions [69] (e.g., differently sized sub-spaces or private spaces where children can explore on their own or hide away from larger groups, mobility license [39,70]) | Affords getting lost, disappearing | Disappear/get lost |

2.2. Study Exclusion Criteria

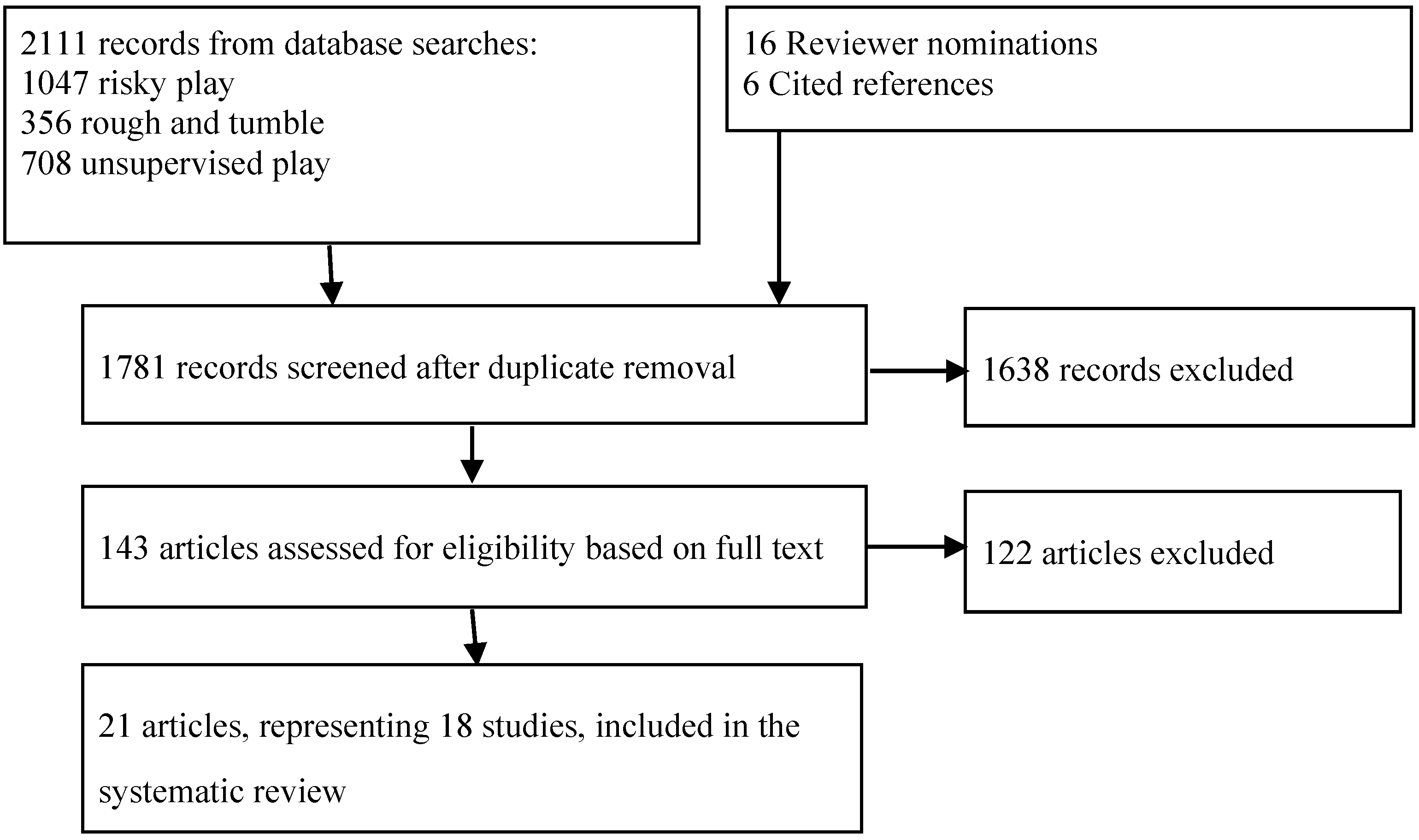

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

2.5. Analysis

3. Results

| Quality Assessment | No. of Participants | Absolute Effect (95% CI, SE) | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | |||

| Habitual physical activity (age range between 10 and 15 years, data collected over a single session up to a 5 year follow-up, habitual physical activity measured using accelerometry, pedometry, and scores on the Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children) | |||||||||

| 5 | Observational studies a | No serious risk of bias b | No serious inconsistency c | Serious indirectness d | No serious imprecision | None | 3915 e | F388 = 6.2, p = 0.013 | VERY LOW |

| F467 = 7.3, p = 0.017 | |||||||||

| F388 = 6.2, p = 0.013 | |||||||||

| F467 = 5.8, p = 0.017 | |||||||||

| F388 = 3.7, p = 0.040 | |||||||||

| F388 = 3.4, p = 0.049 | |||||||||

| Boys % time LPA = 26.2 (7.3), MVPA 5.9 (3.6), p < 0.05 | |||||||||

| Girls % time LPA 23.7 (7.6), MVPA 3.9 (2.5), p < 0.05 f | |||||||||

| b = 29.3, SE2 ± 9.57 | |||||||||

| CI: 9.39–50.06, p < 0.01 | |||||||||

| b = 32.43 ± 13.53 | |||||||||

| CI: 3.23–61.62, p = 0.03 g | |||||||||

| P7 boys high IM = 87.4%, low IM = 74.8%, p = 0.012 | |||||||||

| OR = 2.44, CI: 1.10–5.41, p < 0.05 | |||||||||

| S2 girls high IM = 36.2%, low IM = 16.9%, p = 0.002 | |||||||||

| OR = 4.50, CI: 1.95–10.4, p < 0.05 h | |||||||||

| r = 0.180, p = 0.001; r = 0.112, p = 0.001; r = 0.188, p = 0.001 | |||||||||

| r = 0.092, p = 0.005 | |||||||||

| Beta = 33.55, CI: 19.23, 47.87, x = 4.59, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Beta = 17.89, CI: 6.20, 29.58, x = 3.00, p = 0.003 | |||||||||

| Beta = 24.13 (4.40, 43.78), x = 2.41, p = 0.016 | |||||||||

| Beta = 30.48 (16.73, 44.23), x = 4.35, p = 0.001 | |||||||||

| Beta = 21.03 (8.43, 33.64), x = 3.27, p = 0.001 i | |||||||||

| OR = 1.58 ± 0.228, CI: 1.19–2.10, p = 0.002 | |||||||||

| OR = 1.49 ± 0.194, CI: 1.16–1.93, p = 0.002 | |||||||||

| OR = 1.47 ± 0.236, CI: 1.08–2.02, p = 0.015 j | |||||||||

| Acute physical activity (age range between 0 and 18 years, data were collected over the course of one week, up to 2 months, acute PA measured through accelerometry and direct observation using SOPARC) | |||||||||

| 1 | Observational studies k | No. serious risk of bias | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness l | Serious imprecision m | None | 2712 | Estimate = −0.592, SE = 0.125, t = −4.73, p < 0.0001 | VERY LOW |

| OR = 0.55 (0.30–0.79); | |||||||||

| Estimate = −0.592, SE = 0.125, t = −4.73, p < 0.0001 | |||||||||

| OR = 0.69 (0.42–0.95) n | |||||||||

| Social competence(age range between 7 and 12 years, data were collected during one session, social health was measured through semi-structured maternal interview) | |||||||||

| 1 | Observational studies ° | High risk of bias p | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision q | None | 251 | r = 0.37, p < 0.001; r = 0.15, p < 0.05; r = 0.16 p < 0.05; r = −0.15, p < 0.05 r | VERY LOW |

| Quality Assessment | No. of Participants | Absolute Effect (95% CI, SE) | Quality | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | ||||

| Acute physical activity (age range between 3 and 9.99 years, data collected over a single session up to a 2 year follow-up, acute physical activity measured through direct observation with observer behaviour mapping and accelerometry) | ||||||||||

| 1 | RCT | Low risk of bias a | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision b | None | 221 | 11.2 ± 0.9 min/day MVPA, 10.0 ± 0.9 min/day MVPA | MODERATE | |

| Coefficient = 1.82 | ||||||||||

| CI: 0.5–3.1, p = 0.006 | ||||||||||

| 72,100 ± 14,700 counts, 7200 ± 13,800 counts | ||||||||||

| Coefficient = 9.35 | ||||||||||

| CI: 3.5–15.2, p = 0.002 c | ||||||||||

| 4 | Observational studies d | Serious risk of bias e | No serious inconsistency f | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision g | None | 552 | 1612 CPM (SD = 491), p = 0.014 | VERY LOW | |

| es = 0.9 SD h | ||||||||||

| 39%, p < 0.05 i | ||||||||||

| 75 min; H = 26.6, p < 0.01 j | ||||||||||

| Habitual physical activity (age range between 4.7 and 7.3 years, data collected at baseline, 13 weeks, and 2 years follow-up, habitual physical activity measured through accelerometry) | ||||||||||

| 1 | RCT | No serious risk of bias a | No serious inconsistency k | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision b | None | 221 | MODERATE | ||

| Habitual sedentary behaviour (age range between 4.7 and 7.3 years, data collected at baseline, 13 weeks, and 2 years follow-up, habitual sedentary behaviour measured through accelerometry) | ||||||||||

| 1 | RCT | No serious risk of bias a | No serious inconsistency l | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision b | None | 221 | MODERATE | ||

| Acute sedentary behaviour (age range between 4.7 and 7.3 years, data collected at baseline, 13 weeks, and 2 years follow-up, habitual physical activity measured through accelerometry) | ||||||||||

| 1 | RCT | No serious risk of bias a | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision b | None | 221 | 22.7 ± 9.9 min/day, 23.2 ± 10.3 min/day; | MODERATE | |

| coefficient = −2.13; CI: −3.8–(−0.5), p = 0.01 m | ||||||||||

| Antisocial behaviour (age range between 5 and 9.99 years, distance between pre- and post-measures not reported, aggression measured through direct observation with observer behaviour mapping) | ||||||||||

| 1 | Observational study n | Serious risk of bias a | No serious inconsistency p | No serious indirectness q | No serious imprecision r | None | ~400 | VERY LOW | ||

| Quality Assessment | No. of Participants | Absolute Effect (95% CI, SE) | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | |||

| Bone fractures (age range between 5 and 12 years, data collected over 1 year, bone fractures measured using incident reporting sheets) | |||||||||

| 1 | Observational studies a | No serious risk of bias | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision b | None | 25,782 | 58% ≤59”; 33% 60–79”; 9% >79” c | VERY LOW |

| Quality Assessment | No. of Participants | Absolute Effect (95% CI, SE) | Quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Studies | Design | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other Considerations | |||

| Social competence (age range between 42 months and 11.2 years, data collected over a single session up to 2 years, aspects of social competence were measured using teacher-report questionnaire, peer nominations of popularity and rejection, social cognitive problem solving task, observer rated) | |||||||||

| 5 | Observational studies a | Serious risk of bias b | Serious inconsistency c | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision d | None | 359 e | r = 0.30; p < 0.05; R = 0.09 | VERY LOW |

| r = 0.28; p < 0.05; R = 0.07 | |||||||||

| r = −0.28, p < 0.05; R = 0.07 | |||||||||

| r = 0.28, p < 0.05, R = 0.07 | |||||||||

| r = −0.32, p < 0.05; R = 0.10 | |||||||||

| r = −0.30, p < 0.05; R = 0.09 f | |||||||||

| r = 0.42, p = 0.37 g | |||||||||

| Year 1: r = 0.22 p < 0.05; r = −0.37, p < 0.01 | |||||||||

| year 2: r = 0.25, p < 0.05 | |||||||||

| Year 1 RTP to 2 social variables: r = 0.28, p < 0.01 h | |||||||||

| r = 0.34, p < 0.05; r = 0.54, p < 0.01 | |||||||||

| B = −0.87, R2 = 0.14, p = 0.03 | |||||||||

| B = 1.39, R2 = 0.32, p = 0.001 | |||||||||

| B = 3.30, R2 = 0.22, p = 0.006 i | |||||||||

| r = 0.30; r = 0.30, p < 0.05 j | |||||||||

| r = 0.56, p < 0.01 k | |||||||||

| Anti-social behavior (age range between 64 months and 13.5 years, data were collected over 8 months up to 22 months, aspects of anti-social behaviour were was measured using direct observation, teacher ratings, and a video behaviour discrimination task) | |||||||||

| 2 | Observational studies l,m | No serious risk of bias n | Serious inconsistency ° | No serious indirectness | Serious imprecision p | None | 176 q | P (RTP leading to aggression) = 0.28%, z = 4.00, p < 0.05 | VERY LOW |

| χ2(40, N = 42) = 8.17, p < 0.004); r = 0.47, p < 0.01 r | |||||||||

| r = 0.29, p < 0.01 | |||||||||

| P (RTP rough leads to aggression) = 2.26%, p < 0.05s | |||||||||

3.1. Play Where Children can Disappear/Get Lost

3.1.1. Habitual Physical Activity

3.1.2. Acute Physical Activity

3.1.3. Social Competence

3.2. Great Heights

3.3. Rough and Tumble Play

3.3.1. Social Competence

3.3.2. Anti-Social Behaviour

3.4. Risky Play Supportive Environments

3.4.1. Acute Physical Activity

3.4.2. Habitual Physical Activity

3.4.3. Habitual Sedentary Behaviour

3.4.4. Acute Sedentary Behaviour

3.4.5. Anti-Social Behaviour

3.4.6. Social Behaviour

3.5. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Files

Supplementary File 1Acknowledgements

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boholm, M. The semantic distinction between “risk” and “danger”: A linguistic analysis. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, M. Risk and blame: Essays in cultural theory; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, D.J.; Gill, T.; Spiegal, B. Managing risk in play provision: Implementation guide; Play England: London, UK, 2012; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D.; Tulloch, J. “Risk is part of your life”: Risk epistemiologies among a group of Australians. Sociology 2002, 36, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H.; Kennair, L.E.O. Children’s risky play from an evolutionary perspective: The anti-phobic effects of thrilling experiences. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Categorising risky play—How can we identify risk-taking in children’s play? Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2007, 15, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Characteristics of risky play. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2009, 9, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, H.; Eager, D. Risk, challenge and safety: Implications for play quality and playground design. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An Introduction to Early Childhood; Waller, T.; Davis, G. (Eds.) SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014; p. 440.

- Waters, J.; Maynard, T. What’s so interesting outside? A study of child-initiated interaction with teachers in the natural outdoor environment. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillemyr, O.F. Taking Play Seriously: Children and Play in Early Childhood Education—An Exciting Challenge; IAP: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2009; p. 199. [Google Scholar]

- Brussoni, M.; Olsen, L.L.; Pike, I.; Sleet, D. Risky play and children’s safety: Balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2012, 9, 3134–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyver, S.; Tranter, P.; Naughton, G.; Little, H.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bundy, A. Ten Ways to Restrict Children’s Freedom to Play: The Problem of Surplus Safety. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2009, 11, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A. Physical risk-taking: Dangerous or endangered? Early Years 2003, 23, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelen, L.; Bundy, A.C.; Naughton, G.; Simpson, J.M.; Bauman, A.; Ragen, J.; Baur, L.; Wyver, S.; Tranter, P.; Niehues, A.; Schiller, W.; Perry, G.; Jessup, G.; van der Ploeg, H.P. Increasing physical activity in young primary school children—It’s child’s play: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev. Med. 2013, 56, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavrysen, A.; Bertrands, E.; Leyssen, L.; Smets, L.; Vanderspikken, A.; De Graef, P. Risky-play at school. Facilitating risk percetpion and competence in young children. Eur.Early Child Educ. 2015, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hüttenmoser, M. Children and their living surroundings: Empirical investigation into the significance of living surroundings for the everyday life and development of children. Child. Environ. 1995, 12, 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, T. No fear: Growing up in a risk averse society; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation: London, England, UK, 2007; p. 94. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M. Too safe for their own good; McClelland & Stewart: Toronto, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Heggie, T.W.; Heggie, T.M.; Kliewer, C. Recreational travel fatalities in US national parks. J. Travel Med. 2008, 15, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Visitor Use Statistics. Available online: https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/Reports/National (accessed on 26 November 2014).

- Hagel, B. Skiing and snowboarding injuries. Med. Sport Sci. 2005, 48, 74–119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Child & Youth Unintentional Injury: 10 Years in Review; Safe Kids Canada: Toronto, Canada, 2007; pp. 1–35.

- Vollman, D.; Witsaman, R.; Comstock, R.D.; Smith, G.A. Epidemiology of playground equipment-related injuries to children in the United States, 1996-2005. Clin. Pediatr. 2009, 48, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belechri, M.; Petridou, E.; Kedikoglou, S.; Trichopoulos, D. Sports injuries among children in six European union countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2001, 17, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahai, V.S.; Ward, M.S.; Zmijowskyj, T.; Rowe, B.H. Quantifying the iceberg effect for injury: using comprehensive community health data. Can. J. Public Heal. 2005, 96, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Child and youth injury in review, 2009 edition: Spotlight on consumer product safety; Public Health Agency of Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rivara, F. Counterpoint: minor injuries may not be all that minor. Inj. Prev. 2011, 17, 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pless, I.B. On preventing all injuries. Inj. Prev. 2012, 18, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molcho, M.; Pickett, W. Some thoughts about “acceptable” and “non-acceptable” childhood injuries. Inj. Prev. 2011, 17, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Paediatric Society. Preventing Playground Injuries: Position Statements and Practice Points. Available online: www.cps.ca/documents/position/playground-injuries (accessed on 8 June 2015).

- Hudson, S.; Thompson, D.; Mack, M.G. The prevention of playground injuries. J. Sch. Nurs. 1999, 15, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Canadian Standards Association. CAN/CSA-Z614-14 - Children’s playspaces and equipment, 5th ed.; Canadian Standards Association: Toronto, ON, 2014; p. 165. [Google Scholar]

- Herrington, S.; Nicholls, J. Outdoor play spaces in Canada: the safety dance of standards as policy. Crit. Soc. Policy 2007, 27, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information National Trauma Registry Minimum Data Set, 1994–1995 to 2011–2012. Canadian Institute for Health Information: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013.

- Fuselli, P.; Yanchar, N.L. Preventing playground injuries. Paediatr. Child Health 2012, 17, 328–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Howard, A.W.; MacArthur, C.; Willan, A.; Rothman, L.; Moses-McKeag, A.; MacPherson, A.K. The effect of safer play equipment on playground injury rates among school children. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 172, 1443–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canadian Playground Safety Institute Comparison Table of CSA Z614 Standard Requirements. Available online: http://www.cpsionline.ca/UserFiles/File/EN/sitePdfs/trainingCPSI/StandardsComparisonChart-2007-03-29.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2015).

- Herrington, S.; Lesmeister, C.; Nicholls, J.; Stefiuk, K. Seven C’s: An informational guide to young children's outdoor play spaces; Consortium for Health, Intervention, Learning and Development (CHILD): Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Woolley, H.; Lowe, A. Exploring the relationship between design approach and play value of outdoor play spaces. Landsc. Res. 2013, 38, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.J. Policy issues and risk-benefit trade-offs of “safer surfacing” for children’s playgrounds. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2004, 36, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.P.; Wilson, J.S.; Chalmers, J.D.; Wilson, D.B.; Eager, D.; McIntosh, S.A. Analysis of Energy Flow During Playground Surface Impacts. J. Appl. Biomech. 2013, 29, 628–633. [Google Scholar]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Corbett, M.; Brison, R.J. Identifying predictors of medically-attended injuries to young children: do child or parent behavioural attributes matter? Inj. Prev. 2009, 15, 220–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Kane, A.; Zdzieborski, D. “I think he is in his room playing a video game”: parental supervision of young elementary-school children at home. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landen, M.G.; Bauer, U.; Kohn, M. Inadequate supervision as a cause of injury deaths among young children in Alaska and Louisiana. Pediatrics 2003, 111, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzer, P.G.; Dowd, M.D.; Kruse, R.L.; Morrongiello, B.A. Supervision and risk of unintentional injury in young children. Inj. Prev. 2014. injuryprev–2013–041128–. [Google Scholar]

- Chelvakumar, G.; Sheehan, K.; Hill, L.A.; Lowe, D.; Mandich, N.; Schwebel, C.D. The Stamp-in-Safety programme, an intervention to promote better supervision of children on childcare centre playgrounds: an evaluation in an urban setting. Inj. Prev. 2010, 16, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Zdzieborski, D.; Sandomierski, M.; Munroe, K. Results of a randomized controlled trial assessing the efficacy of the Supervising for Home Safety program: Impact on mothers’ supervision practices. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 50, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishion, T.J.; McMahon, R.J. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 1998, 1, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Corbett, M.R.; Kane, A. A measure that relates to elementary school children’s risk of injury: The Supervision Attributes and Risk-Taking Questionnaire (SARTQ). Inj. Prev. 2011, 17, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racz, S.J.; McMahon, R.J. The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: a 10-year update. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwebel, D.C.; Roth, D.L.; Elliott, M.N.; Windle, M.; Grunbaum, J.A.; Low, B.; Cooper, S.P.; Schuster, M.A. The association of activity level, parent mental distress, and parental involvement and monitoring with unintentional injury risk in fifth graders. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 848–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, M.; Montana, B.; Panettieri, M. A nursing intervention to ensure a safe playground environment. J. Pediatr. Healthc. 1996, 10, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, L. It all used to be better? Different generations on continuity and change in urban children’s daily use of space. Child. Geogr. 2005, 3, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K. The bubble-wrap generation: Children growing up in walled gardens. Environ. Educ. Res. 2007, 13, 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Macvarish, J.; Bristow, J. Risk, health and parenting culture. Health. Risk Soc. 2010, 12, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofferth, S.L. Changes in American children’s time - 1997 to 2003. Electron. Int. J. Time Use Res. 2009, 6, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, B.; Watson, B.; Frauendienst, B.; Redecker, A.; Jones, T.; Hillman, M. Children’s independent mobility: A comparative study in England and Germany (1971-2010); Policy Studies Institute: London, England, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, D.G.; Singer, J.L.; D’Agostino, H.; DeLong, R. Children’s pastimes and play in sixteen nations: Is free-play declining? Am. J. Play 2008, 1, 283–312. [Google Scholar]

- Clements, R. An investigation of the status of outdoor play. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childhood and Nature: A Survey on Changing Relationships with Nature across Generations; Natural England: Warboys, England, UK, 2009; p. 32.

- Phelan, K.J.; Khoury, J.; Kalkwarf, H.J.; Lanphear, B.P. Trends and patterns of playground injuries in United States children and adolescents. Ambul. Pediatr. 2001, 1, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, L.; Holtslag, H.R.; Leenen, L.P.H.; Lindeman, E.; Looman, C.W.N.; van Beeck, E.F. Trends in moderate to severe paediatric trauma in Central Netherlands. Injury 2014, 45, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jago, R.; Thompson, J.L.; Page, A.S.; Brockman, R.; Cartwright, K.; Fox, K.R. Licence to be active: Parental concerns and 10-11-year-old children’s ability to be independently physically active. J. Public Health. 2009, 31, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalish, M.; Banco, L.; Burke, G.; Lapidus, G. Outdoor play: A survey of parent’s perceptions of their child's safety. J. Trauma 2010, 69, S218–S222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alparone, F.R.; Pacilli, M.G. On children’s independent mobility: the interplay of demographic, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Child. Geogr. 2012, 10, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandy, C.A. Children’s diminishing play spaces: A study of inter-generational change in children's use of their neighbourhoods. Aust. Geograpical Stud. 1999, 37, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brussoni, M.; Brunelle, S.; Pike, I.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Herrington, S.; Turner, H.; Belair, S.; Logan, L.; Fuselli, P.; Ball, D.J. Can child injury prevention include healthy risk promotion? Inj. Prev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Affordances for risky play in preschool: The importance of features in the play environment. Early Child. Educ. J. 2009, 36, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S.; Lesmeister, C. The design of landscapes at child-care centres: Seven Cs. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Board 101st Session, Resolutions and Decisions, EB101.1998/REC/l; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 52–53.

- Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004; p. 21.

- Khambalia, A.; Joshi, P.; Brussoni, M.; Raina, P.; Morrongiello, B.; Macarthur, C. Risk factors for unintentional injuries due to falls in children aged 0-6 years: A systematic review. Inj. Prev. 2006, 12, 378–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mytton, J.; Towner, E.; Brussoni, M.; Gray, S. Unintentional injuries in school-aged children and adolescents: Lessons from a systematic review of cohort studies. Inj. Prev. 2009, 15, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Akl, E.A.; Kunz, R.; Vist, G.; Brozek, J.; Norris, S.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Glasziou, P.; DeBeer, H.; Jaeschke, R.; Rind, D.; Meerpohl, J.; Dahm, P.; Schünemann, H.J. GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmons, B.W.; Leblanc, A.G.; Carson, V.; Connor Gorber, S.; Dillman, C.; Janssen, I.; Kho, M.E.; Spence, J.C.; Stearns, J.A.; Tremblay, M.S. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0–4 years). Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 37, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, J.; Levin, K.; Inchley, J. Parental and peer influences on physical activity among Scottish adolescents: a longitudinal study. J. Phys. Act. Heal. 2011, 8, 785–793. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.; Cooper, A.; Griew, P. Independent mobility in relation to weekday and weekend physical activity in children aged 10–11 years: The PEACH Project. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, A.S.; Cooper, A.R.; Griew, P.; Jago, R. Independent mobility, perceptions of the built environment and children’s participation in play, active travel and structured exercise and sport: the PEACH Project. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, M.R.; Faulkner, G.E.; Mitra, R.; Buliung, R.N. The freedom to explore: examining the influence of independent mobility on weekday, weekend and after-school physical activity behaviour in children living in urban and inner-suburban neighbourhoods of varying socioeconomic status. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoeppe, S.; Duncan, M.J.; Badland, H.M.; Oliver, M.; Browne, M. Associations between children’s independent mobility and physical activity. BMC Public Health 2014, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormack, G.; Giles-Corti, B. A cross-sectional study of the individual, social, and built environmental correlates of pedometer-based physical activity among elementary school children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2011, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floyd, M.F.; Bocarro, J.N.; Smith, W.R.; Baran, P.K.; Moore, R.C.; Cosco, N.G.; Edwards, M.B.; Suau, L.J.; Fang, K. Park-based physical activity among children and adolescents. Amer. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prezza, M.; Pilloni, S.; Morabito, C.; Sersante, C.; Alparone, F.R.; Giuliani, M.V. The influence of psychosocial and environmental factors on children’s independent mobility and relationship to peer frequentation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 11, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, A.C.; Luckett, T.; Tranter, P.J.; Naughton, G.A.; Wyver, S.R.; Ragen, J.; Spies, G. The risk is that there is “no risk”: a simple, innovative intervention to increase children’s activity levels. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2009, 17, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, C.S.; Pinciotti, P. Changing a schoolyard: Intentions, design decisions, and behavioral outcomes. Environ. Behav. 1988, 20, 345–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storli, R.; Hagen, T.L. Affordances in outdoor environments and children’s physically active play in pre-school. Eur. Early Child. Educ. Res. J. 2010, 18, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, D.G.; Rothenberg, M.; Beasley, R.R. Children’s play and urban playground environments: A comparison of traditional, contemporary, and adventure playground types. Environ. Behav. 1974, 6, 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Rubie-Davies, C.M.; Townsend, M.A.R. Fractures in New Zealand elementary school settings. J. Sch. Health 2007, 77, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, A.D. A longitudinal study of boys’ rough-and-tumble play and dominance during early adolescence. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1995, 16, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWolf, D. Preschool children’s negotiation of intersubjectivity during rough and tumble play. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Colwell, M.J.; Lindsey, E.W. Preschool Children’s Pretend and Physical Play and Sex of Play Partner: Connections to Peer Competence. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A. Elementary-school children’s rough-and-tumble play and social competence. Dev. Psychol. 1988, 24, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D. Elementary school children’s rough-and-tumble play. Early Child. Res. Q. 1989, 4, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D. A longitudinal study of popular and rejected children’s rough-and-tumble play. Early Educ. Dev. 1991, 2, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, A.D. Boys’ rough-and-tumble play, social competence and group composition. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 1993, 11, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldberg, H. Reclaiming childhood: Freedom and play in an age of fear; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S.A.; Frohlich, K.L.; Fusco, C. Playing for health? Revisiting health promotion to examine the emerging public health position on children’s play. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandseter, E.B.H. Restrictive safety or unsafe freedom? Norwegian ECEC Practitioners’ perceptions and practices concerning children's risky play. Child Care Pract. 2012, 18, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.Y.; Sumanth Kumar, G.; Mahadev, A. Severity of playground-related fractures: more than just playground factors? J. Pediatr. Orthop. 2013, 33, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkin, P.C.; Howard, A.W. Advances in the prevention of children's injuries: an examination of four common outdoor activities. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2008, 20, 719–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norton, C. Playground injuries to children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2004, 89, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nauta, J.; Martin-Diener, E.; Martin, B.W.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E. Injury risk during different physical activity behaviours in children: A systematic review with bias assessment. Sport. Med. 2014, 45, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, P.; Mikkelsen, M.R.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Harder, H. Children, mobility, and space: Using GPS and mobile phone technologies in ethnographic research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2011, 5, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Dawber, T. Parental influences on toddlers’ injury-risk behaviors: Are sons and daughters socialized differently? J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 1999, 20, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, B.A.; Zdzieborski, D.; Normand, J. Understanding gender differences in children’s risk taking and injury: A comparison of mothers' and fathers' reactions to sons and daughters misbehaving in ways that lead to injury. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2010, 31, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.N.; Peterson, L. Gender differences in children’s outdoor play injuries: A review and an integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 10, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegal, M. Are sons and daughters treated more differently by fathers than by mothers? Dev. Rev. 1987, 7, 183–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towner, E.M.; Jarvis, S.N.; Walsh, S.S.; Aynsley-Green, A. Measuring exposure to injury risk in schoolchildren aged 11-14. Br. Med. J. 1994, 308, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soori, H.; Bhopal, R.S. Parental permission for children’s independent outdoor activities: Implications for injury prevention. Eur. J. Public Health 2002, 12, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, D.C. Male, female: The evolution of human sex differences; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, D.; Murray, S.J.; Perron, A.; Rail, G. Deconstructing the evidence-based discourse in health sciences: truth, power and fascism. Int. J. Evid. Based. Healthc. 2006, 4, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petticrew, M. Why certain systematic reviews reach uncertain conclusions. BMJ 2003, 326, 756–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaster, S. Urban children’s access to their neighborhood: Changes over three generations. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 70–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. “Oh yes I can.”“Oh no you can’t”: Children and parents’ understandings of kids’ competence to negotiate public space safely. Antipode 1997, 29, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, A.; Timperio, A.; Crawford, D. Playing it safe: the influence of neighbourhood safety on children’s physical activity. A review. Health Place 2008, 14, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Play Safety Forum. Managing risk in play provision: A position statement; Play England: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF Child Friendly Cities. Available online: http://childfriendlycities.org/ (accessed on 23 July 2014).

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brussoni, M.; Gibbons, R.; Gray, C.; Ishikawa, T.; Sandseter, E.B.H.; Bienenstock, A.; Chabot, G.; Fuselli, P.; Herrington, S.; Janssen, I.; et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 6423-6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606423

Brussoni M, Gibbons R, Gray C, Ishikawa T, Sandseter EBH, Bienenstock A, Chabot G, Fuselli P, Herrington S, Janssen I, et al. What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015; 12(6):6423-6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606423

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrussoni, Mariana, Rebecca Gibbons, Casey Gray, Takuro Ishikawa, Ellen Beate Hansen Sandseter, Adam Bienenstock, Guylaine Chabot, Pamela Fuselli, Susan Herrington, Ian Janssen, and et al. 2015. "What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12, no. 6: 6423-6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606423

APA StyleBrussoni, M., Gibbons, R., Gray, C., Ishikawa, T., Sandseter, E. B. H., Bienenstock, A., Chabot, G., Fuselli, P., Herrington, S., Janssen, I., Pickett, W., Power, M., Stanger, N., Sampson, M., & Tremblay, M. S. (2015). What is the Relationship between Risky Outdoor Play and Health in Children? A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6423-6454. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606423