Abstract

With an apparent increase of harmful algal blooms (HABs) worldwide, healthcare providers, public health personnel and coastal managers are struggling to provide scientifically-based appropriately-targeted HAB outreach and education. Since 1998, the Florida Poison Information Center-Miami, with its 24 hour/365 day/year free Aquatic Toxins Hotline (1–888–232–8635) available in several languages, has received over 25,000 HAB-related calls. As part of HAB surveillance, all possible cases of HAB-related illness among callers are reported to the Florida Health Department. This pilot study evaluated an automated call processing menu system that allows callers to access bilingual HAB information, and to speak directly with a trained Poison Information Specialist. The majority (68%) of callers reported satisfaction with the information, and many provided specific suggestions for improvement. This pilot study, the first known evaluation of use and satisfaction with HAB educational outreach materials, demonstrated that the automated system provided useful HAB-related information for the majority of callers, and decreased the routine informational call workload for the Poison Information Specialists, allowing them to focus on callers needing immediate assistance and their healthcare providers. These results will lead to improvement of this valuable HAB outreach, education and surveillance tool. Formal evaluation is recommended for future HAB outreach and educational materials.

Keywords:

Poison Information Centers; Harmful algal bloom (HAB); outreach and education; Florida red tide; ciguatera fish poisoning; blue green algae; cyanobacteria; brevetoxins; ciguatoxins; human health effects; neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP); paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP); Solutions to Avoid Red Tide (START); Karenia brevis. 1. Introduction

Harmful algal blooms (HABs) are caused by blooms of algae known as phytoplankton; these include organisms such as dinoflagellates, diatoms and cyanobacteria [1–6]. HABs can occur in all aquatic environments. In marine environments, they are also known as “red tides” because some of these organisms can change the color of the water to red or brown. HABs may cause harm to the environment and other organisms in two ways. First, through the severe overgrowth of the HAB organisms that depletes oxygen in the local environment, and second when the HAB organisms produce extremely potent natural toxins.

Phytoplankton are the base of the marine food web; thus, the toxins they produce can bioconcentrate in organisms higher up in the food chain. Several human illnesses are caused by the ingestion of seafood contaminated with the natural toxins produced by the HAB organisms [1–6]. In addition to exposure through seafood ingestion, environmental exposures can occur through skin contact with contaminated water or by inhalation when the HAB organisms are broken up by waves and their toxins become aerosolized. For example, human exposure to aerosols containing brevetoxins from the Florida red tide dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, has been associated with reports of respiratory distress, particularly but not exclusively in persons with asthma, as well as increased emergency room admissions for pneumonia, bronchitis and asthma among coastal residents during active Florida red tides [7–12].

With the increasing number of persons interacting with the coastal areas (both freshwater and marine) and with the apparent increase of HABs around the world, healthcare providers, public health personnel, and coastal managers are struggling to provide scientifically-based information [13–17]. There is a paucity of appropriately targeted outreach and educational materials for healthcare providers and persons with possible exposure to the marine and freshwater toxins, as well as coastal resource managers, the media, and the general public. A variety of educational outreach materials and services have been created, but there has been almost no formal evaluation to determine whether these materials are reaching their target audiences and meeting these audiences’ expectations.

1.1. Florida Poison Information Centers

The Florida Poison Information Center/Miami (FPIC/Miami) is one of three poison centers created in the State of Florida in 1989 by an act of the Florida Legislature (FS 395.038), and it has rapidly grown into a cost-effective model of a poison center system. The FPIC/Miami is located at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and Jackson Health Systems, and directly serves the residents of Southeastern Florida (i.e. Miami-Dade, Broward, Monroe, Palm Beach, Lee and Collier counties) and beyond with toll-free 24 hour/day services in several languages. For example, in 2006 the FPIC/Miami responded to over 57,340 calls; of these calls, 35,741 (62%) were for known or suspected exposures to toxic substances. Approximately 80% of the patients calling from home were managed in the home, without the need for an emergency department visit. The FPIC/Miami placed 18,833 (33%) follow-up calls to continually assess this home management. The FPIC/Miami toxicologists provided over 1,705 consultations with Florida’s physicians to assist in the care of hospitalized patients. In an attempt to prevent poisonings, the FPIC/Miami educators coordinated 669 outreach and education programs for the lay public, health professional, and the media. They also distributed over 198,213 informational brochures, handouts and telephone stickers, reaching over 72,000 persons.

Since 1998, with funding from the Florida Department of Health, the National Center for Environmental Health (NCEH) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the University of Miami National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences Center and the National Science Foundation (NSF)- NIEHS Oceans and Human Health Center, the FPIC-Miami established a toll-free hotline (1–888–232–8635) dedicated to providing information concerning aquatic health issues. All calls are answered by Poison Information Specialists, who are highly trained physicians and nurses. All calls are reported as a form of passive surveillance of HAB-related illness and information requests to the Aquatic Toxins Program ( http://www.doh.state.fl.us/ENVIRONMENT/community/aquatic/) and to the Foodborne Illness Program of the Florida Department of Health.

Recently, the Hotline was expanded to include additional options for callers. Using an automated call processing menu system, the “Aquatic Toxins Hotline,” now allows callers to access information in English or Spanish about the possible health effects and locations of the Florida red tide (including the National Atmospheric and Oceanographic Administration (NOAA) Harmful Algae Bloom (HAB) Bulletin http://coastwatch.noaa.gov/hab/bulletins_ns.htm), information on ciguatera fish poisoning, blue green algae (cyanobacteria) and resources for learning about general marine toxin issues, as well as still giving the callers the opportunity to select to speak directly to a Poison Information Specialist if they wish. These materials were reviewed and developed with cooperation between the FPIC-Miami, the University of Miami, the Florida Department of Health, the CDC, Mote Marine Laboratory, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission.

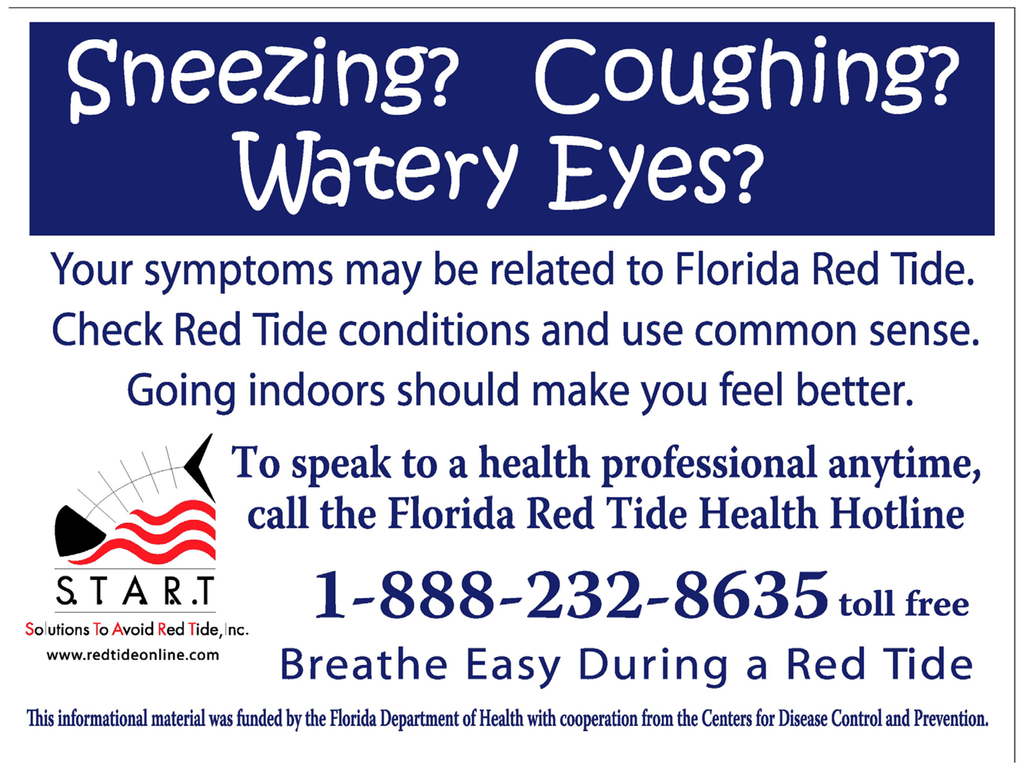

Concurrent with this initiative, a number of academic, public health and community partners (including Solutions to Avoid Red Tide or START; http://www.start1.com/) collaborated to create a series of informational signs advertising the Aquatic Toxins Hotline as a source of information for Florida red tide. After focus groups with public health personnel, beach managers, hotel and restaurant owners, and tourist boards, these signs were designed to be posted on and near beaches, and targeted at beach users including tourists (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Florida Red Tide, START, and Florida Poison Information Center Outreach Informational Signage.

This Pilot Study evaluated whether the new automated system was used by callers and whether the callers considered the information to be useful to them, as well as to collect caller recommendations for the improvement of this service. The goal of this pilot study was to evaluate whether the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline was serving the self-identified needs of current callers.

2. Methods

The FPIC-Miami receives the telephone numbers of all callers to the Aquatic Toxins Hotline, whether the caller speaks with a Poison Information Specialist or just the automated system. In this evaluation, telephone numbers from the calls made to the Aquatic Toxins Hotline from September 2006 through January 2007 were re-contacted. Of note, throughout this study time period, there was an active Florida red tide on the West Coast of Florida.

This evaluation aimed to determine:

- Basic Caller demographics

- What information/services callers were seeking

- Which menu selections were the most commonly chosen

- Which menu options, in the caller’s opinion, were the most helpful

- If callers were satisfied with the service provided by the Aquatic Toxins Hotline

- If callers would call again

- What would, in the callers’ opinion, make the Aquatic Toxins Hotline service more useful.

Trained interviewers contacted the Aquatic Toxins Hotline callers by phone in English and Spanish to explain the study, obtained verbal consent for participation and conducted a short scripted interview (available on request from the corresponding author). Specifically, the interviewers asked a brief series of questions about using the Aquatic Toxins Hotline and about the caller’s perception of the system’s usefulness. Study participants also had an opportunity to make suggestions to improve the system. No personal identifying information was collected. To maximize success in contacting callers, the interviewers called each telephone number three times (once during a week day, once during a week night, and once during the weekend) in an attempt to re-contact the specific person who had called the Aquatic Toxins Hotline.

This study was approved by both the University of Miami and Florida Department of Health Human Subject Committees. The data were collected into a Study Access Database. The data were analyzed using SAS version 9.1. The data were analyzed by frequencies as a descriptive process.

3. Results

The Aquatic Toxins Hotline has experienced increasing use over the past few years, particularly during periods of active Florida red tides. Since its inception in 1998, there have been 25,000 calls to the Hotline, with 7,000 occurring between 2001 and 2006; during 2006 alone, 2,415 calls were made to the Aquatic Toxins Hotline. During the study period from Sept 2/06 through Jan 31/07, there were 1,163 calls made to the hotline, with 315 (27%) answered by a Poison Information Specialist; of these calls, 53% were for Florida red tide, 6% for ciguatera, 17% for jellyfish, 2% each for PSP/pufferfish, scombroid, and stingrays, and 0.6% blue green algae. This means that only 27% of the callers selected to speak with a Poison Information Specialist from the automated HAB Menu in English or Spanish, while the vast majority (73%) only accessed the automated HAB menu.

The Interviewers attempted to contact each of the callers during the study period as described above. Even though the follow-up calls were made within two months of the original contact, only a small percentage (10%) of the callers was able to be re-contacted. Inability to re-contact these individuals was due to a variety of factors such as: no answer despite repeated calls, answering machines, and no real contact number (i.e. original call made from hotel, hospital, etc). Nevertheless, once contacted, all callers (100%) agreed to participate.

A total of 118 callers were successfully re-contacted and agreed to participate. Of these, only 89 callers reported that they recalled making a call to the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline, and thus these 89 callers were considered the participants in this Pilot Study. Of note, both the actual number of respondents and the percentages are reported below because not all subjects answered all the questions.

The majority of the 89 participants were women (41 [61%]), self-described as white (82 [100%]) and non Hispanic (66 [94%]) whose primary language was English (80 [96%]) and with a mean age and standard deviation of 55.5 +/− 12.2 years (see Table 1). The participants were predominantly from Florida (50 [77%]), with the majority from the West coast of Florida (46 [60%]) particularly in Sarasota, the area of recurrent Florida red tide. There were 18 (23%) callers from other parts of the US, including 1 from the US Virgin Islands (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographics of Participants in the Aquatic Toxins Hotline Evaluation.

The majority of the participants had heard about the Aquatic Toxins Hotline from a website (35 [39%]), newspaper or magazine article (16 [18%]), a friend or personal recommendation (13 [15%]), or a sign (7 [8%]). Many of the participants (38 [48%]) called with general information questions; of note, none of the participants reported calling because they or someone they cared for was sick or believed they had been exposed to a toxin.

Overall, the majority of participants (59 [68%]) reported that they received an answer to the question that prompted their call to the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline (see Table 2). Furthermore, 59 (68%) reported that the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline was easy to use, with only 17 (20%) reporting otherwise. Finally, 69 (80%) of the participants reported that they would be likely to use the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline again, and 68 (79%) stated that they would recommend the Hotline to others.

Table 2.

Participant Overall Satisfaction with the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline (Total N=89).

With regards to the specific information supplied by the automated system, 34 (39%) of participants reported speaking with a Poison Information Specialist; among these participants, 23 (74%) were satisfied and only two (7%) were dissatisfied (see Table 3). Among those participants who used the automated HAB menu, the largest number (46 [54%]) reported listening to the NOAA HAB Bulletin which gives current and forecasted information on the location of the Florida red tides; among these participants, 30 (70%) were satisfied and seven (17%) were dissatisfied. The second largest group (37 [44%]) reported listening to general information about Florida red tides; among these participants, 26 (70%) expressed satisfaction, and 8 (22%) were dissatisfied. Participants also reported listening to information about other marine toxin issues (28 [33%]) with 20 (71%) expressing satisfaction; Ciguatera fish poisoning (11 [13%]) with 10 (90%) expressing satisfaction; and blue green algae (cyanobacteria) (10 [12%] with 9 (90%) expressing satisfaction.

Table 3.

Participant Satisfaction with Specific Information Received from the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline (Total N=89).

At the end of the questionnaire, the participants were asked if there was anything in particular they thought should be done to improve the usefulness of the Florida Freshwater and Marine Health Hotline as an open ended question. The majority of the comments can be summarized as: a) wanting more up-to-date information (particularly geographic location of the Florida red tides) on even a daily basis; and b) wanting to speak with a person directly or listening to an automated system. Specifically, the participants recommended that the Hotline provide the geographic location of the Florida red tides on a map; provide more information to tourists in hotels; and make sure that the Poison Information Specialists were up-to-date with HAB and Florida red tide information.

4. Discussion

This study was the first known systematic evaluation of the use of and satisfaction with educational outreach materials for HABs, specifically evaluating callers to an automated Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline of the South Florida Poison Information Center. The majority (68%) of participants reported that they were satisfied with the information provided by the Aquatic Toxins Hotline; 80% that they would use the Hotline again; and 79% that they would recommend the Hotline to others. Furthermore, even when evaluating the specific services offered by the Aquatic Toxins Hotline automated system (including speaking directly with a Poison Information Specialist), the high level of satisfaction persisted. Of interest, only 8% of participants reporting hearing about the Aquatic Toxins Hotline from signs, with the rest learning about the hotline from a website (39%), newspaper or magazine article (18%), or friend (15%). Our evaluation demonstrated that the primary advantage of the new automated system is that it provided useful HAB information for the large majority of the callers, without requiring contact with a Poison Information Specialist. By decreasing the workload of purely informational calls for the Poison Information Specialists, the Hotline allows the Specialists to focus on those persons who need immediate assistance.

4.1. Limitations

As seen in previous studies using the Poison Information data [18,19], only a small percentage (10%) of the callers were able to be re-contacted. This lack of participation in telephone surveys is part of an unfortunate and growing nationwide trend recognized by the evaluation research community [20,21]. Furthermore, the majority of the study participants (77%) gave zip codes of addresses within Florida; since the follow-up calls were made two months from the original call, it would appear that the majority of the participants were either part-time seasonal (i.e., “snow-birds”) or permanent residents. Based on the review of the zip codes and area codes of all Hotline callers, many were likely tourists, and thus were “lost to follow-up” when they could not be reached two months after their original call to the Hotline [20,21].

In addition, these participants were not entirely representative of the overall Hotline caller population since a greater proportion (39%) reported speaking with a Poison Information Specialist than was reported (27%) for the entire population of callers to the Florida Aquatic Toxins Hotline during the study period. However, based on the limited demographic information, the participants interviewed were similar to those contacted in other studies which have used the overall South Florida Poison Information Center Caller Database, i.e., predominantly white non Hispanic older females [18,19]. We did not identify many Hispanic callers in this study. Of note, most of the relevant marine HAB activity is concentrated on the Gulf Coast, while the majority of Florida’s Hispanic population is concentrated on the east coast of Florida. Finally, there were missing data (e.g. 22 out of 89 persons did not report their gender).

5. Discussion and Recommendations

This Pilot Evaluation Study demonstrated that the additional outreach provided by the Hotline was successful in getting information to people who wanted it. It also suggested that there needs to be increased outreach and education efforts using a range of media to inform additional target populations about the Aquatic Toxins Hotline, such as residents and tourists, and their healthcare providers. For example, it has been shown in the case of ciguatera fish poisoning, that even in an endemic area such as Miami (Florida), the majority of healthcare providers do not recognize, nor (more important from the point of view of HAB surveillance) do they report cases of ciguatera to the Health Department even though it is a reportable illness throughout the US [22]. Therefore, additional outreach and education not only to the possible victims of HAB-related illness, but also for their healthcare providers is needed.

Recommendations for improving the Aquatic Toxins Hotline automated HAB system include the following: 1) Existing automated materials need to be revised to incorporate an ongoing evaluation component, with a focus on tourist not just resident callers, and in coordination with ongoing efforts in providing geographic location [23]; 2) Existing materials will need constant updating; and 3) Ongoing training should be provided for the Poison Information Specialists (as well as other healthcare providers) concerning the possible exposures and health effects from the aquatic toxins as new HAB research data and resources are made available [13, 23–29]. In addition, as different HAB educational outreach materials and services are created, these materials and services need to be evaluated before and after implementation in the target populations to improve their quality and utility. Based on the participation rate in this study, rapid follow up is necessary to ensure an effective evaluation. This will require the incorporation of additional resources and collaboration with investigators with expertise in outreach, education and evaluation in future HAB activities.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the interviewers, Poison Information Specialists and callers who participated in this study. The funding for this study was provided by the Florida Department of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Florida Harmful Algal Bloom Taskforce, as well as the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Oceans and Human Health Center at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School (NSF 0CE0432368; NIEHS 1 P50 ES12736), the former National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Marine and Freshwater Biomedical Sciences Center at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School (NIEHS P30ES05705), and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Red Tide POI (P01 ES 10594).

- Sample Availability: Contact the authors.

References

- National Research Council, From Monsoons to Microbes: Understanding the Oceans Role in Human Health; National Academy Press: Washington DC, 1999.

- Backer, LC; Fleming, LE. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Epidemiologic Tools to Investigate Oceans and Public Health. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press Chapter 11.

- Backer, LC; Schurz Rogers, H; Fleming, LE; Kirkpatrick, B; Benson, J. Dabrowski, W, Ed.; Phycotoxins in Marine Seafood. In Chemical and Functional Properties of Food Components: Toxins in Food; CRC Press: Boca Raton FL, 2005; pp. 155–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, LE; Backer, L; Rowan, A. Baden, D, Adams, D, Eds.; The Epidemiology of Human Illnesses Associated with Harmful Algal Blooms. In Neurotoxicology Handbook; Humana Press: Totowa NJ, 2002; pp. 1363–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, LE; Bean, JA; Katz, D; Hammond, R. Hui, Kits, Stanfield, Eds.; The Epidemiology of Seafood Poisoning. In Seafood and Environmental Toxins; Marcel Dekker: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 287–310. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, D; Fleming, LE; Bean, JA. deWolff, F, Ed.; Marine Toxins. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology: Intoxications of the Nervous System Part II Natural Toxins and Drugs FA; Elsevier Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 141–175. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, LE; Kirkpatrick, B; Backer, LC; Bean, JA; Wanner, A; Reich, A; Zaias, J; Cheng, Y-S; Pierce, R; Naar, J; Abraham, WM; Baden, DG. Aerosolized Red Tide Toxins (Brevetoxins) and Asthma. Chest 2007, 131, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Kirkpatrick, B; Fleming, LE; Backer, LC; Bean, JA; Tamer, R; Kirkpatrick, G; Kane, T; Wanner, A; Dalpra, D; Kane, T; Wanner, A; Dalpra, D; Reich, A; Baden, DG. Environmental exposures to Florida red tides: effects on emergency room respiratory diagnoses admissions. Harm Algae 2006, 5, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Kirkpatrick, B; Fleming, LE; Squicciarini, D; Backer, LC; Clark, R; Abraham, W; Benson, J; Cheng, YS; Johnson, D; Pierce, R; Zaias, J; Bossart, G; Baden, DG. Literature review of Florida Red Tide: implications for human health. Harm Algae 2004, 3, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Fleming, LE; Backer, LC; Baden, DG. Overview of Aerosolized Florida Red Tide Toxins: Exposures and Effects. Environ Health Persp 2005, 113, 618–620. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Backer, LC; Fleming, LE; Rowan, A; Cheng, YS; Benson, J; Pierce, R; Zaias, J; Bean, J; Bossart, GD; Johnson, D; Baden, DG. Recreational Exposure to Aerosolized Brevetoxins During Florida Red Tide Events. Harm Algae 2003, 2, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Backer, LC; Kirkpatrick, B; Fleming, LE; Cheng, YS; Pierce, R; Bean, JA; Clark, R; Johnson, D; Wanner, A; Tamer, R; Baden, D. Occupational Exposure to Aerosolized Brevetoxins during Florida Red Tide Events: Impacts on a Healthy Worker Population. Environ Health Persp 2005, 113, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Dewailly, E; Pereg, D; Knap, A; Rouja, P; Galvin, J; Owen, R. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Exposure and effects of seafood borne contaminants in maritime populations. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press Chapter 10.

- Fleming, LE; Jerez, E; Stephan, W; Cassedy, A; Bean, JA; Reich, A; Kirkpatrick, B; Backer, L; Nierenberg, K; Watkins, S; Weisman, R. Florida Marine and Freshwater Health Hotline: Evaluation of New Public Health Components; Florida Poison Information Center; University of Miami; Florida Department of Health; CDC; Childrens Hospital Cincinnati; Mote Marine Laboratory: Miami FL, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, LE; Broad, K; Clement, A; Dewailly, E; Elmir, S; Knap, A; Pomponi, SA; Smith, S; Solo Gabriele, H; Walsh, P. Oceans and Human Health: Emerging Public Health Risks in the Marine Environment. Mar Pollut Bull 2006, 53, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Kirkpatrick, B; Fleming, LE; Stephan, W; Backer, L; Reich, A; Dalpra, D; Weisman, R; Van de Bogart, G. Public Outreach Materials regarding HABs and their possible effects on Human Health. Presented at International Harmful Algal Bloom Meeting, Capetown, South Africa, November 2004.

- Fleming, LE; Baden, DG; Bean, JA; Weisman, R; Blythe, DG. Reguera, B, Blanco, J, Fernandez, ML, Wyatt, T, Eds.; Seafood toxin diseases: Issues in Epidemiology and community outreach. In Harmful Algae; Xunta de Galicia and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO: Galicia, 1998; pp. 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Squicciarini, D; Fleming, LE; Weisman, R; Tamer, R. Pediatric Pesticide Poisoning in South Florida. Fl J Env Health 2003, 183, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Quirino, W; Fleming, LE; Weisman, R; Backer, L; Kirkpatrick, B; Clark, R; Dalpra, D; Van de Bogart, G; Gaines, M. Follow-up study of red tide associated respiratory illness. Fl J Env Health 2004, 186, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Groves, RM; Biemer, PP; Lyberg, LL; Massey, JT; Nicholls, WL; Waksberg, J. Telephone Survey Methodology 2001.

- Dillman, DA. Mail and Telephone Surveys: The Total Design Method; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- McKee, D; Fleming, LE; Tamer, R; Weisman, R. Hallegraeff, GM, Blackburn, SI, Bolch, CJ, Lewis, RJ, Eds.; Ciguatera Fish Poisoning Reporting by physicians in an endemic area. In Harmful Algal Blooms 2000; IOC of UNESCO: Paris, 2001; pp. 451–453. [Google Scholar]

- Steidinger, KA; Landsberg, JH; Flewelling, JL; Kirkpatrick, B. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Toxic Dinoflagellates. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press; Chapter 13.

- Trainer, VL; Hickey, BM; Bates, SS. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Toxic Diatoms. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press; Chapter 12.

- Bienfang, PK; Parsons, ML; Bidigare, RR; Laws, EA; Moeller, PDR. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Ciguatera fish poisoning: a synpopsis from ecology to toxicity. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press; Chapter 14.

- Vogelbein, WK; Lovko, VJ; Reece, KS. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Pfiesteria. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press; Chapter 16.

- Stewart, I; Falconer, IR. Walsh, PJ, Smith, SL, Fleming, LE, Solo Gabriele, HM, Gerwick, WH, Eds.; Cyanobacteria and cyanobacterial toxins. In Oceans and Human Health: Risks and Remedies from the Sea; Elsevier Science Publishers: New York NY, in press; Chapter 15.

- Watkins, SM; Reich, A; Fleming, LE; Hammond, RA. Neurotoxic Shellfish Poisoning. Mar Drugs 2007, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, MA; Fleming, LE; Bienfang, P; Fernandez, M; Schrank, K; Dickey, B; Backer, L; Bottein, MY; Weisman, R; Ayyar, R. Ciguatera Fish Poisoning: Treatment and Management. Mar Drugs 2007, in press. [Google Scholar]