Structure Meets Function: Dissecting Fucoxanthin’s Bioactive Architecture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fucoxanthin Biological Activities

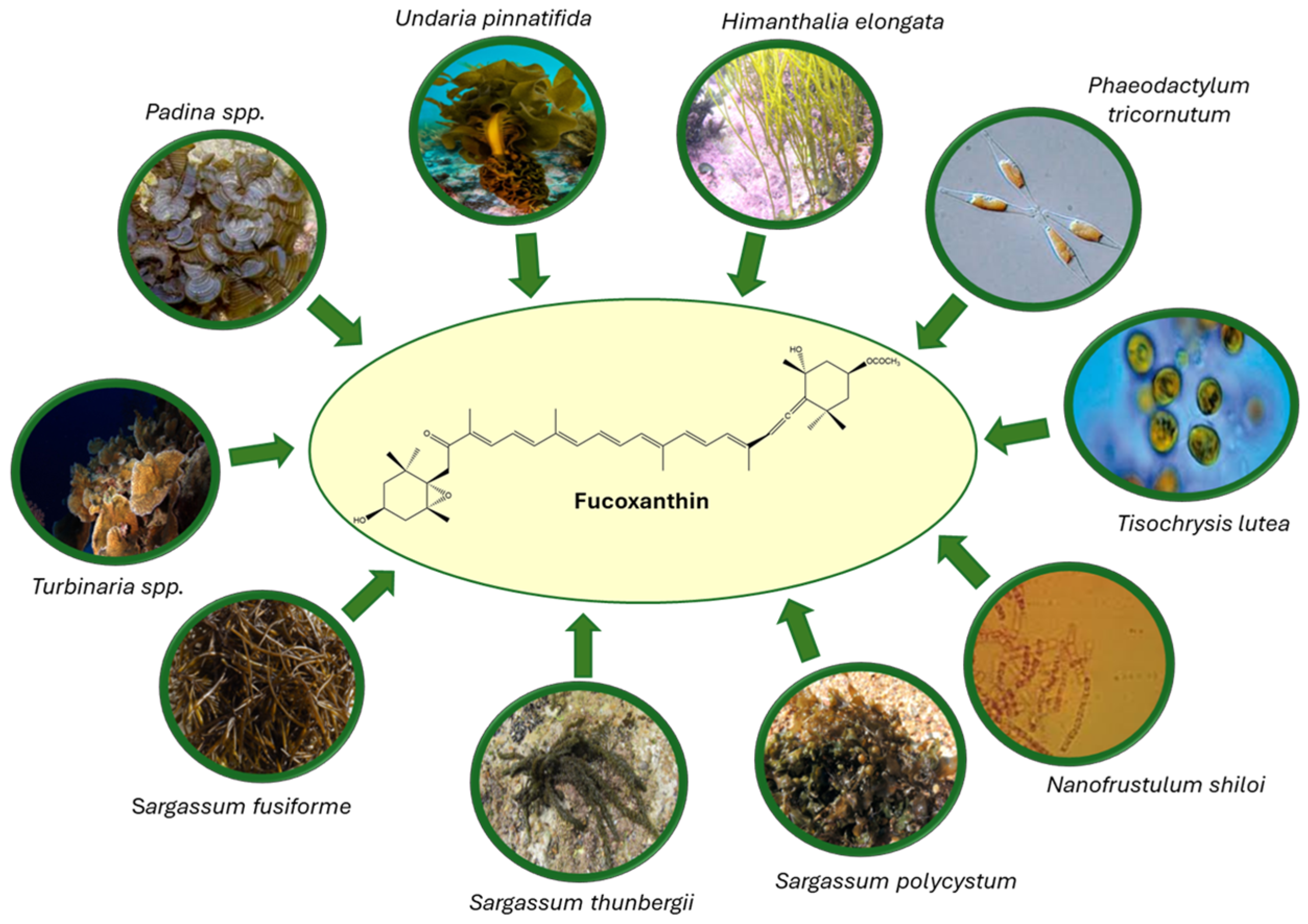

2.1. Natural Sources

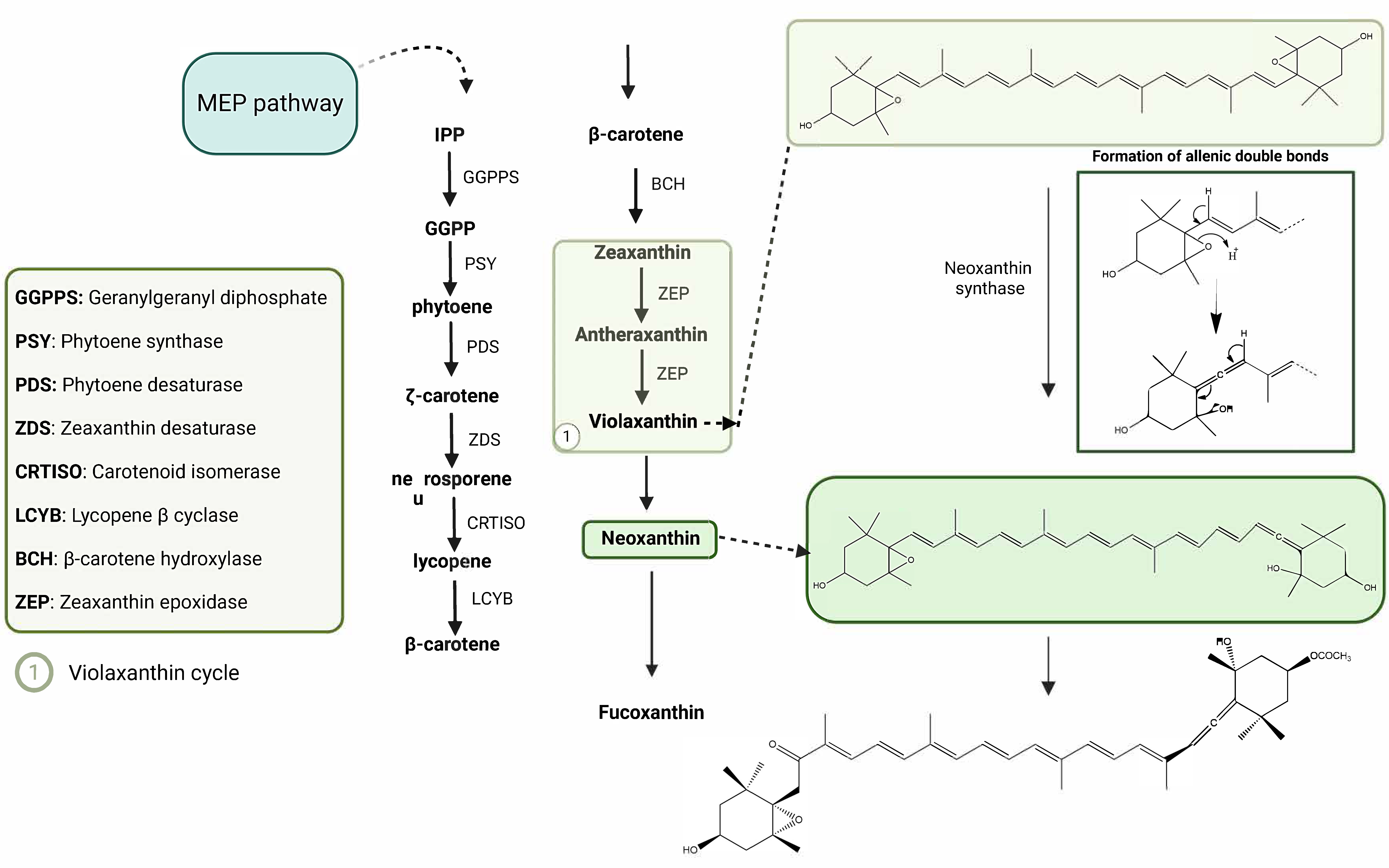

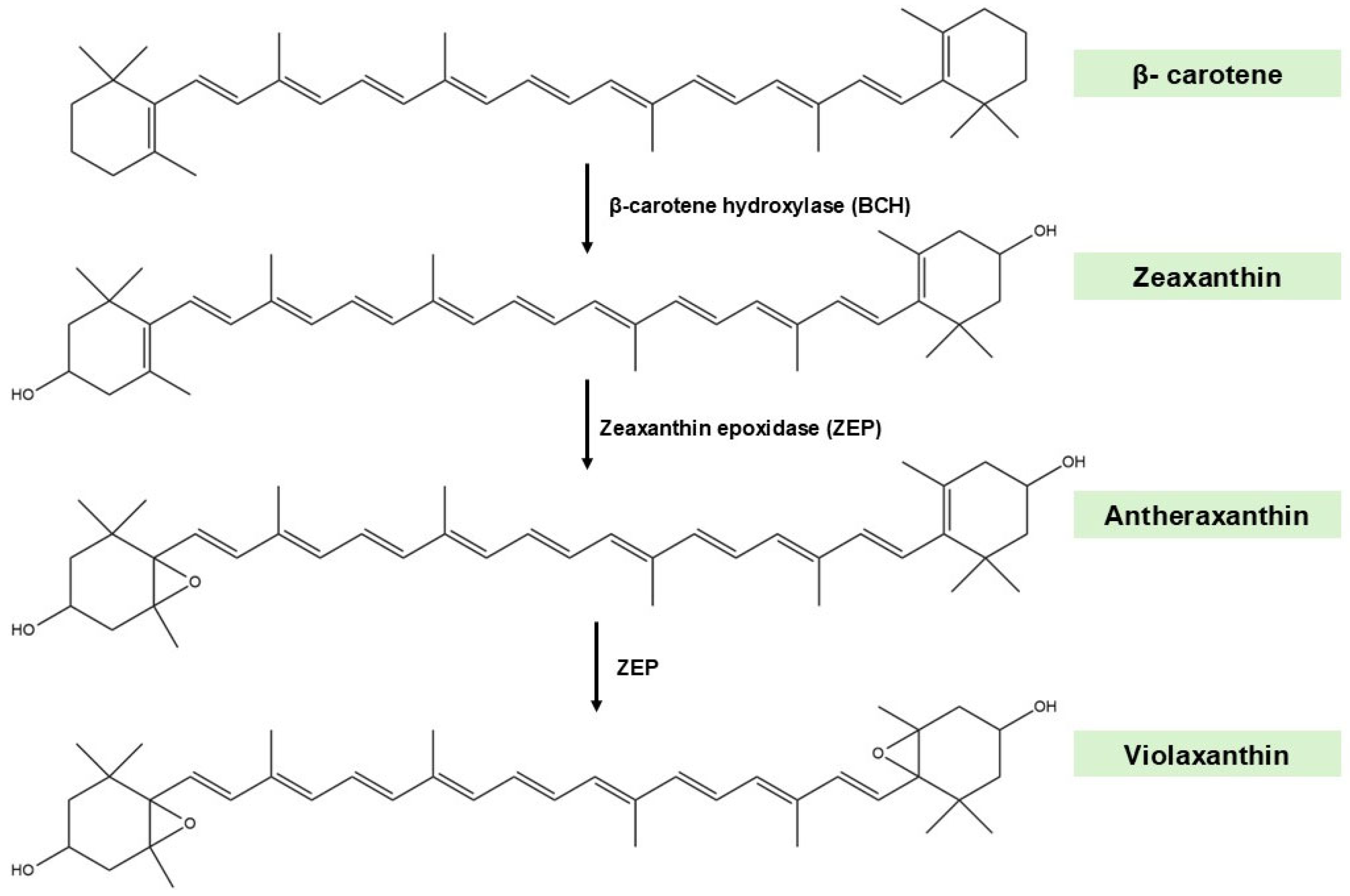

2.2. Biosynthetic Pathways

2.3. Biological Activities

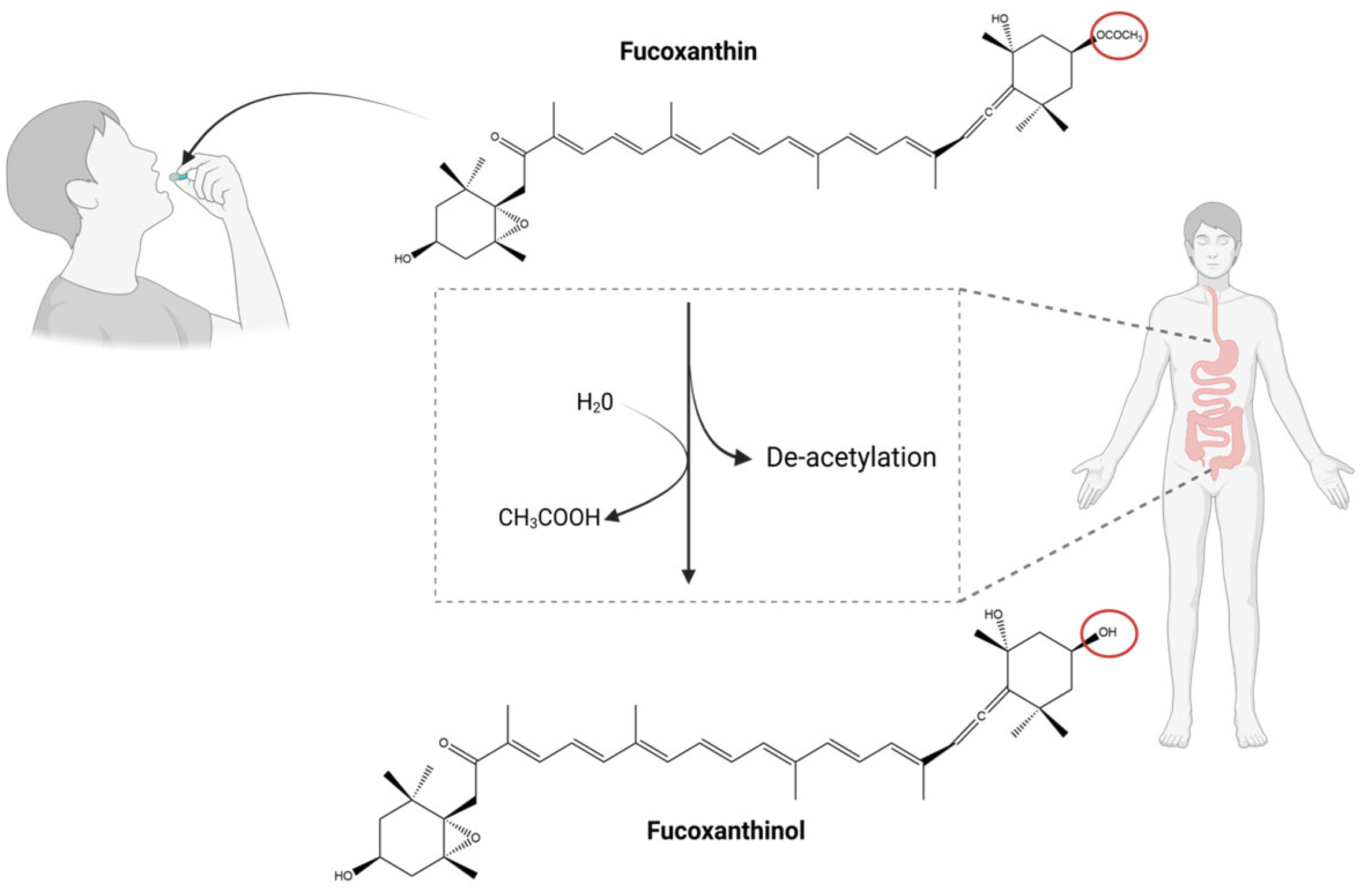

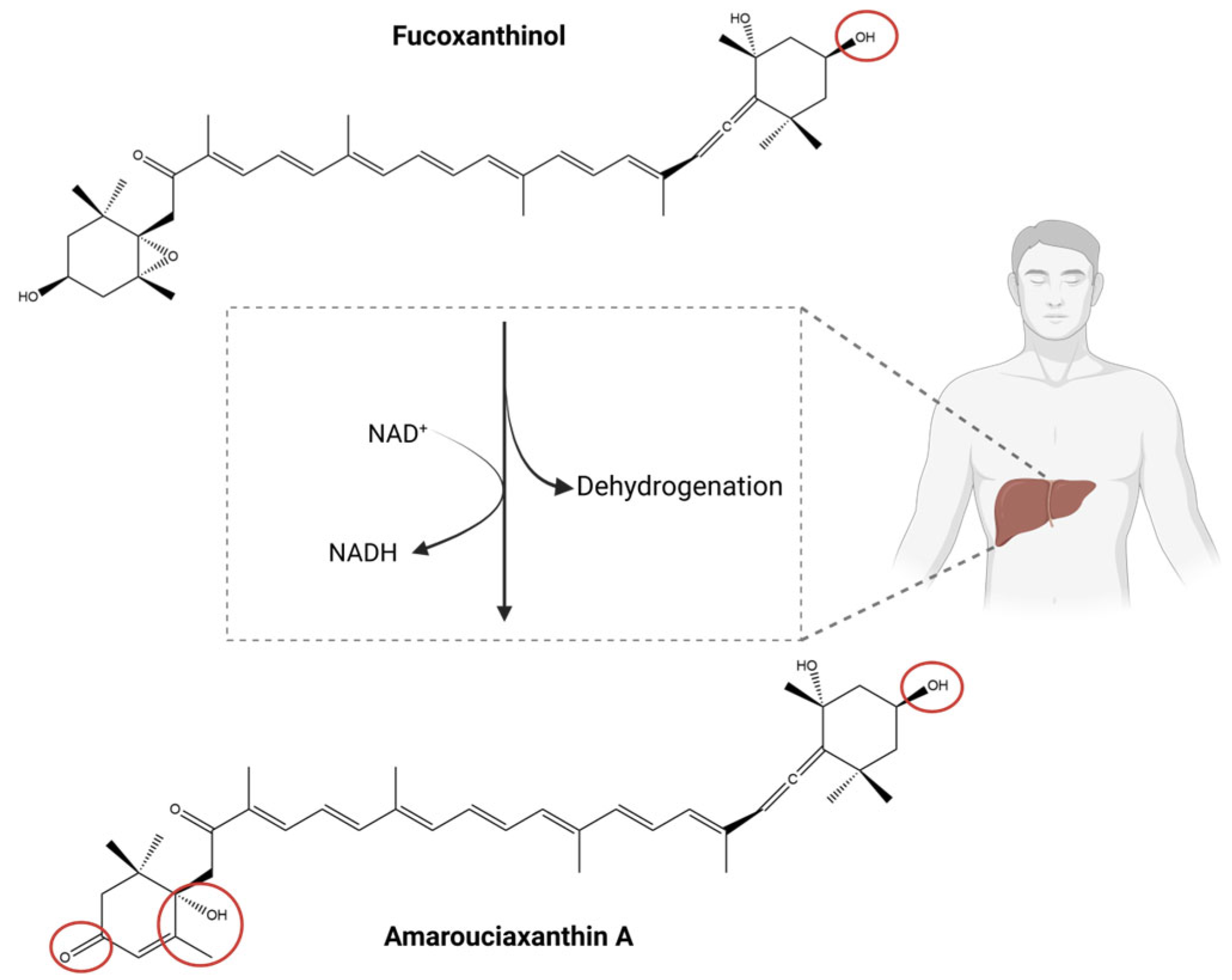

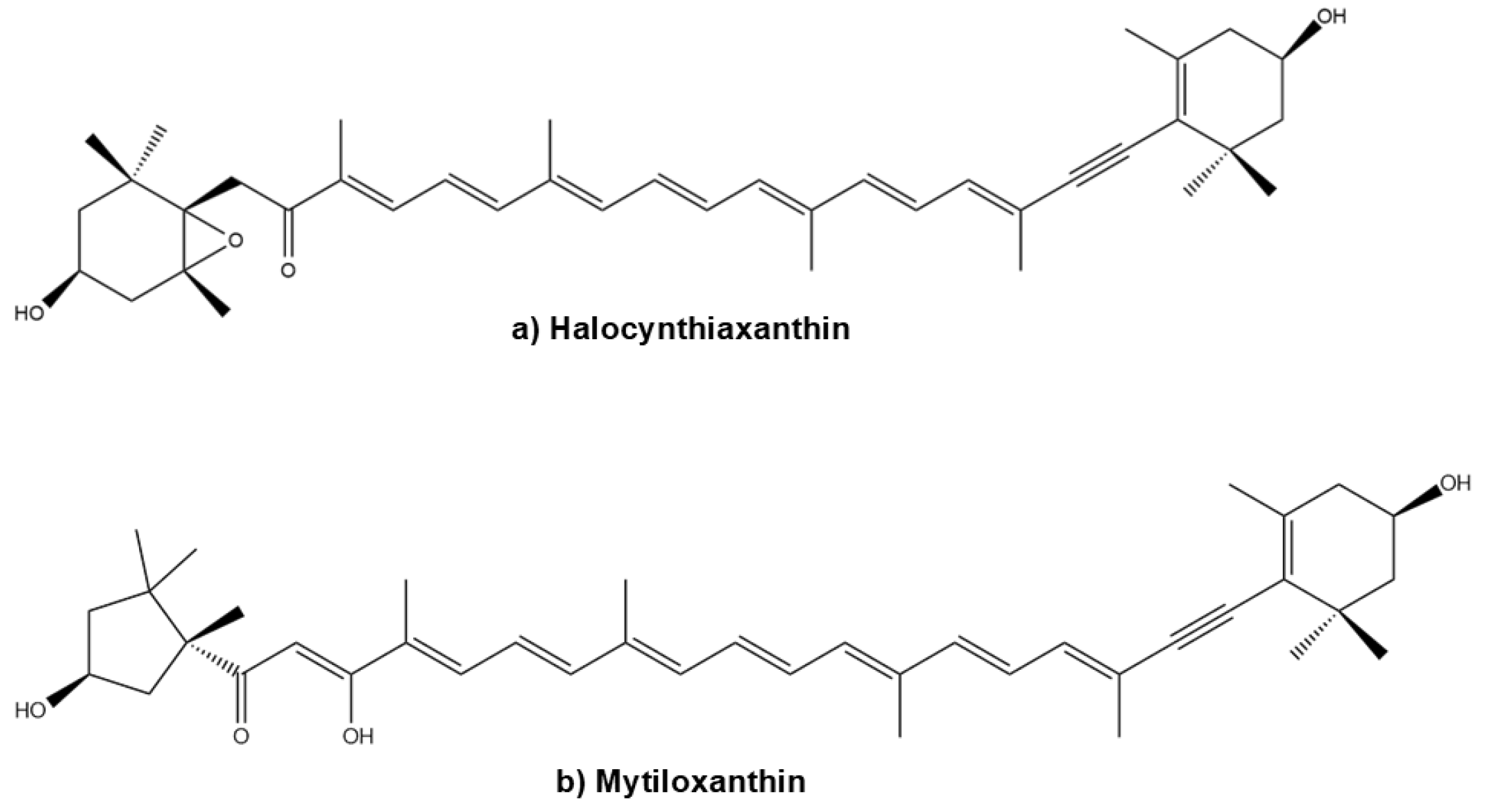

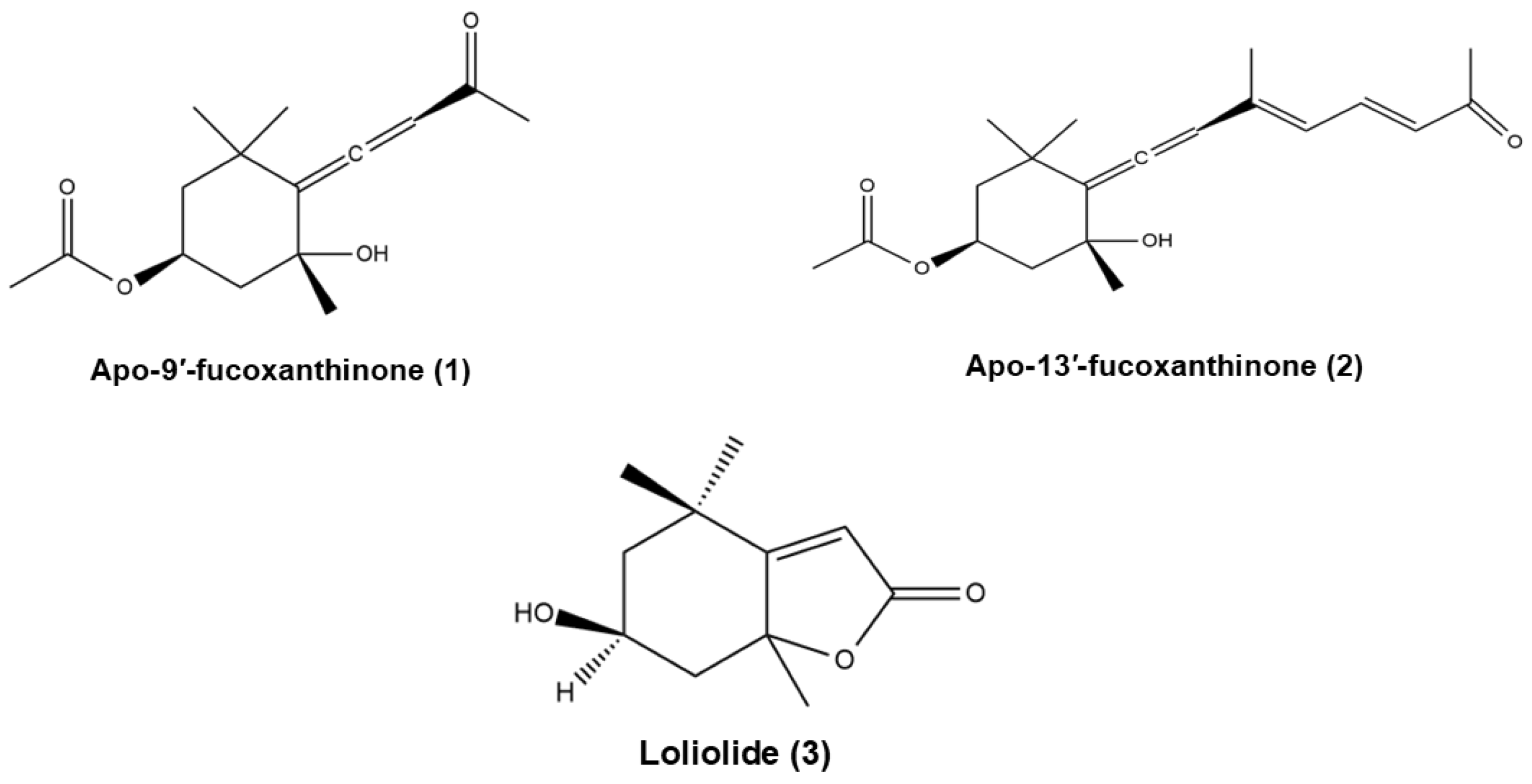

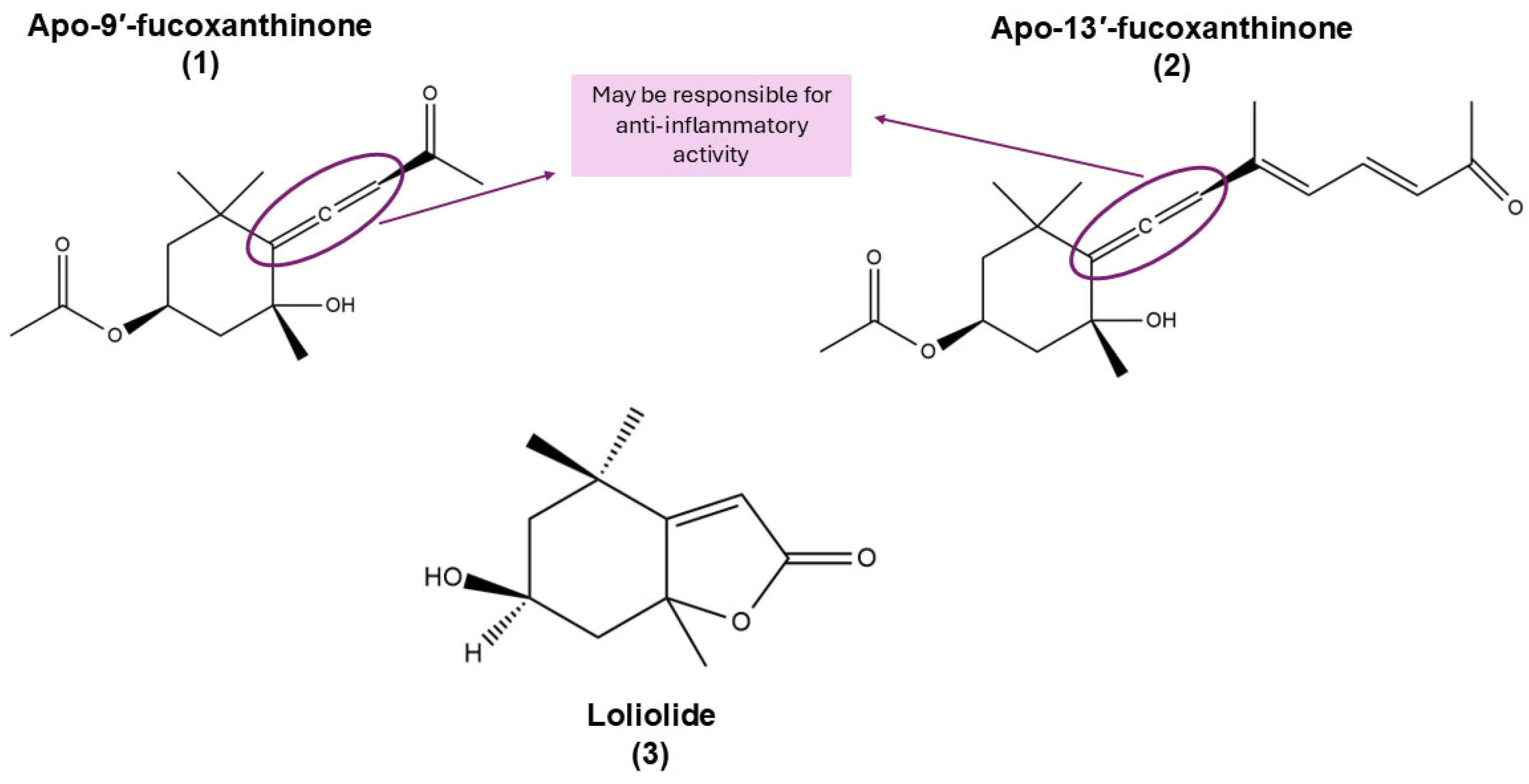

3. Natural Derivatives of Fucoxanthin

4. Integrated Overview of the Bioactivities of Fx and Its Derivatives

5. Signalling Pathways Modulated by Fx’s Metabolites

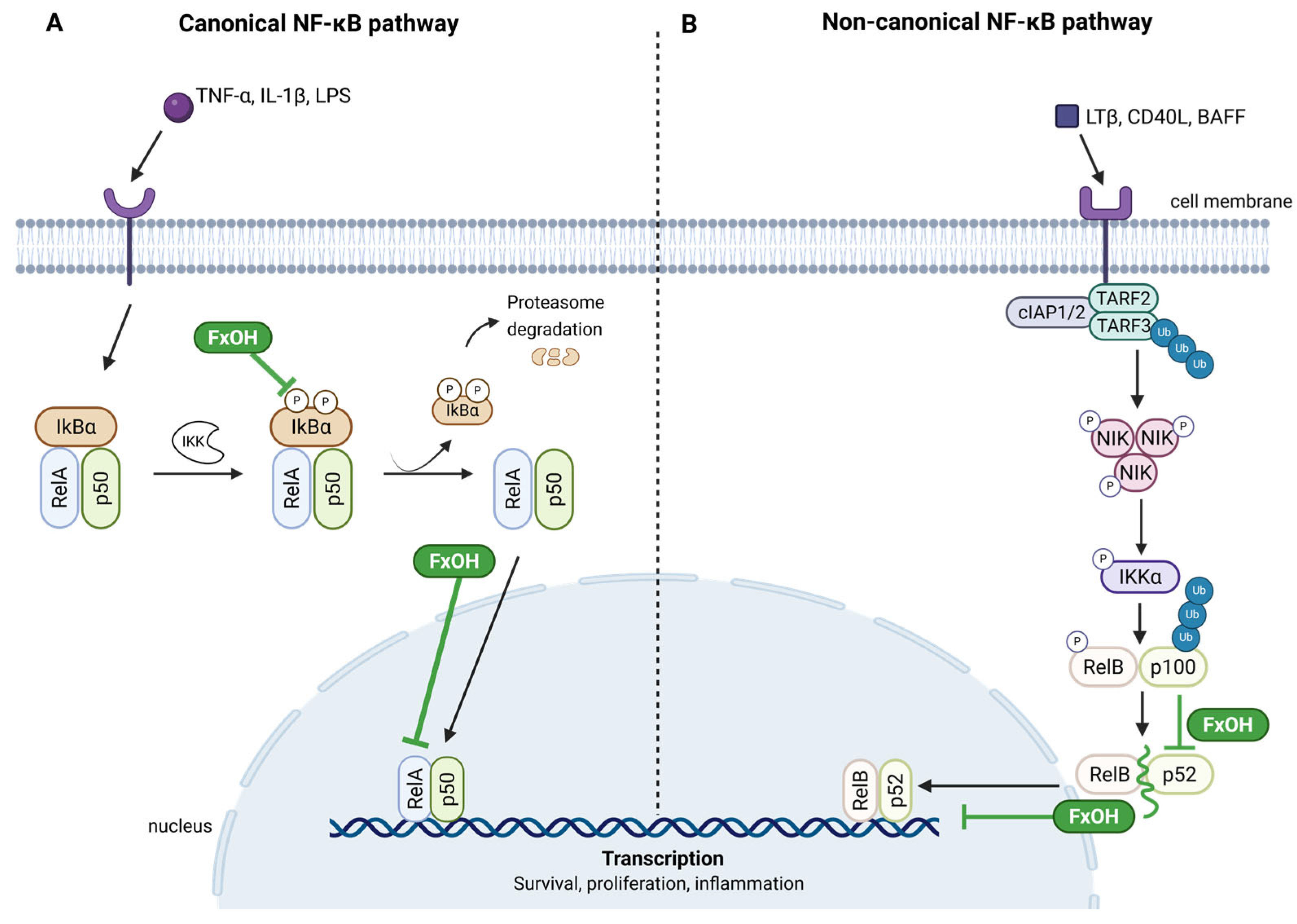

5.1. NF-κB Pathway

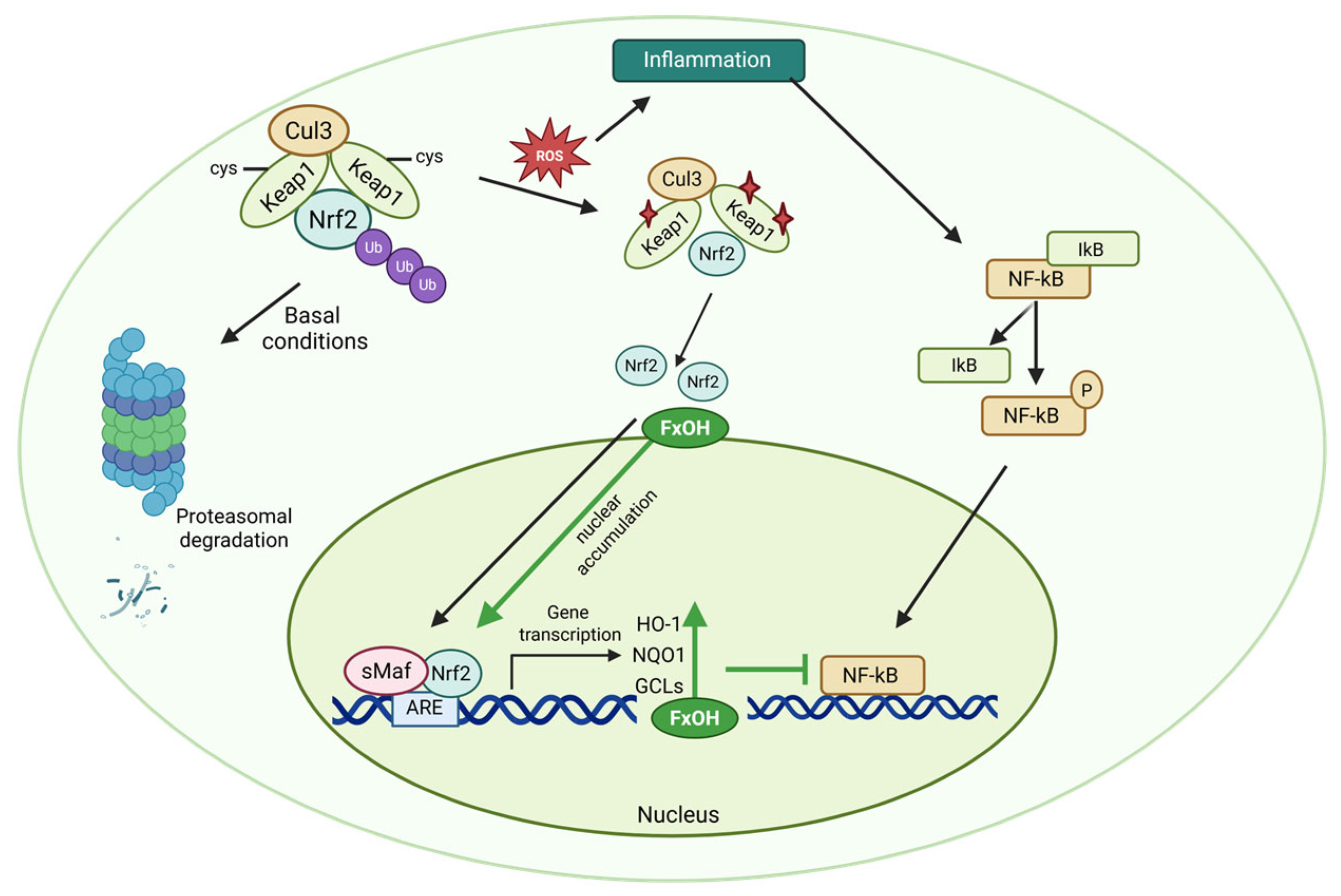

5.2. Nrf-2 Pathway

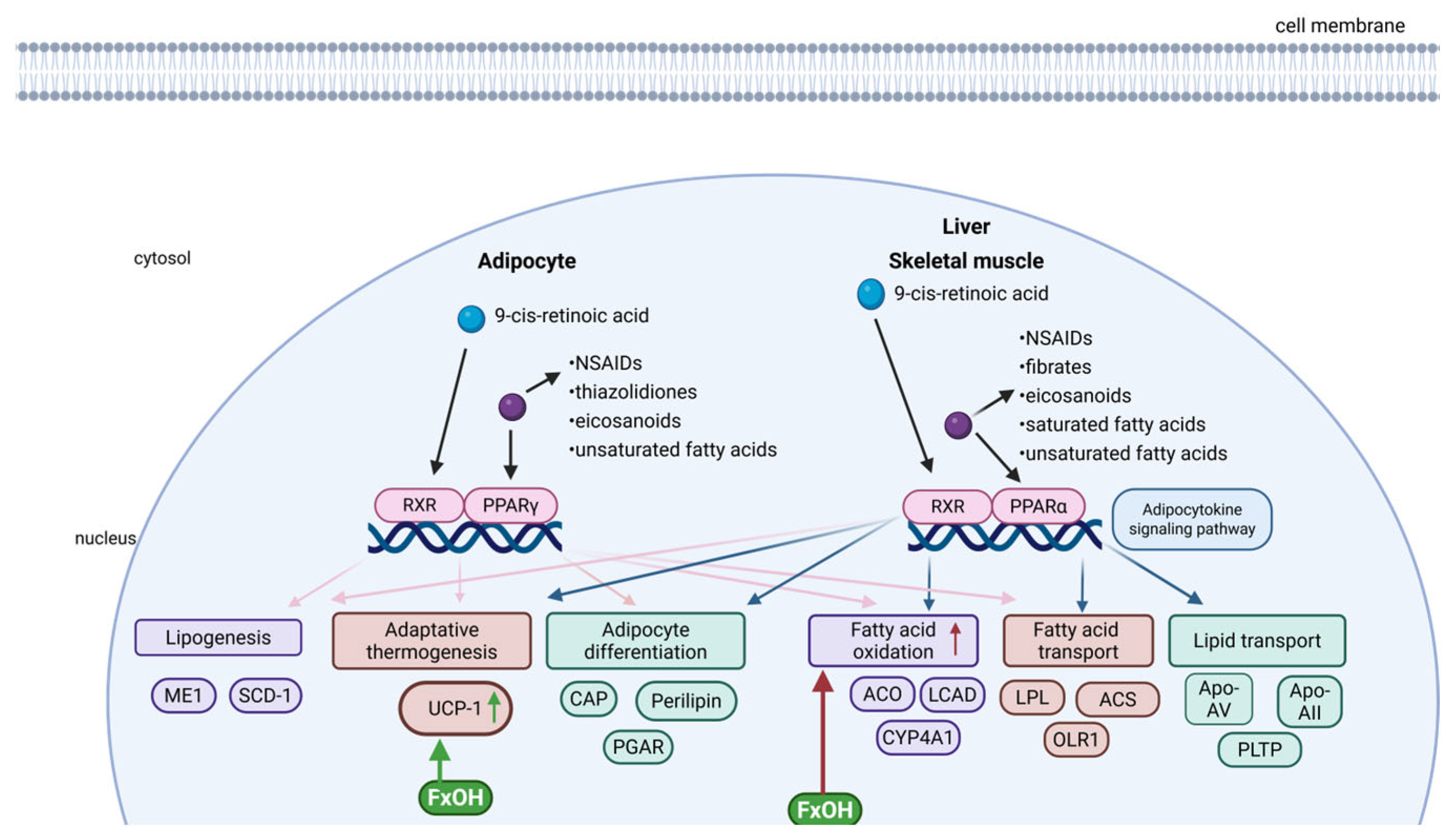

5.3. PPARs Signalling Pathway

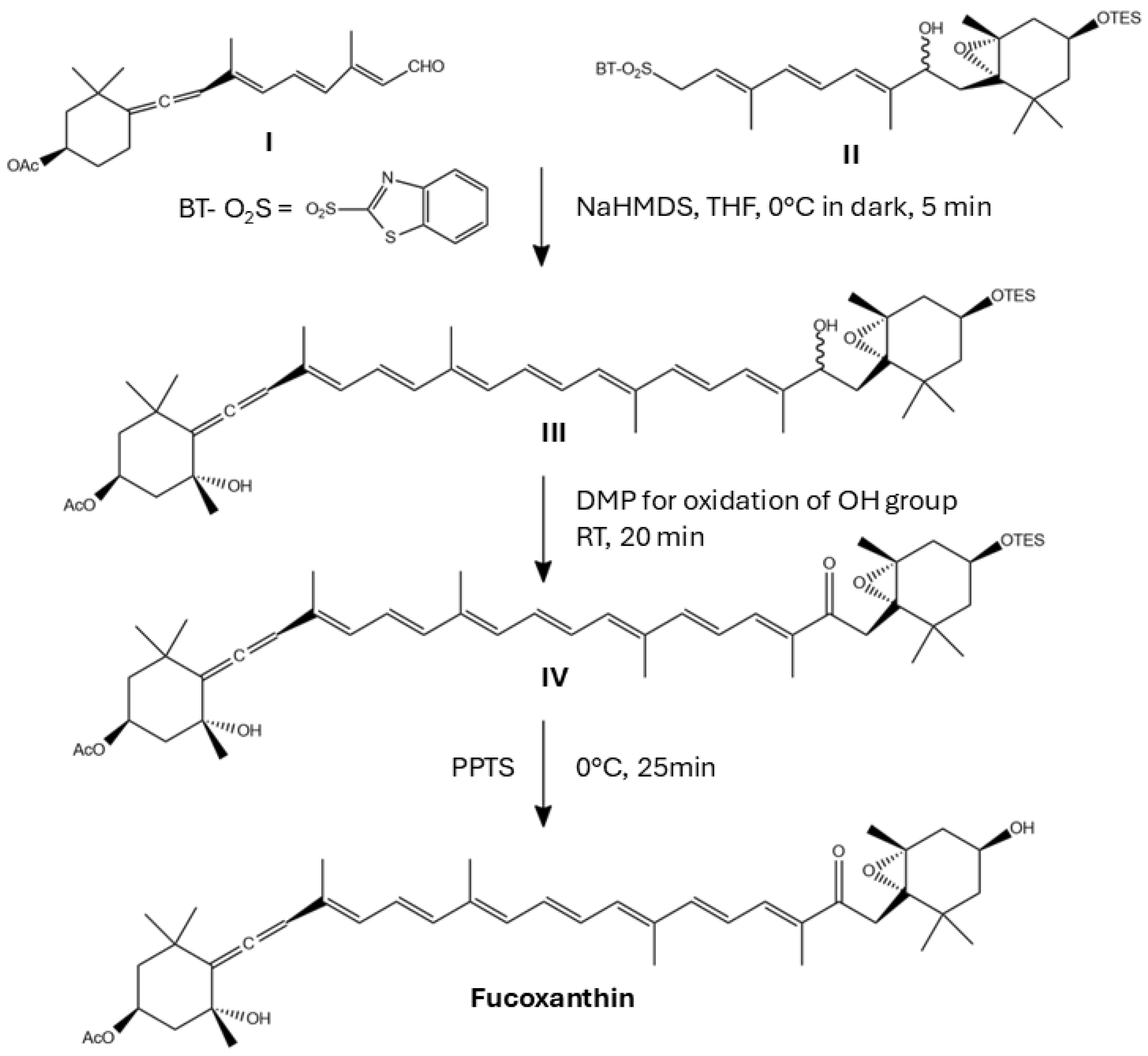

6. Challenges to Obtain Synthetic Fx and Fx Derivatives

7. Bioactivity of Synthetic Fx Derivatives

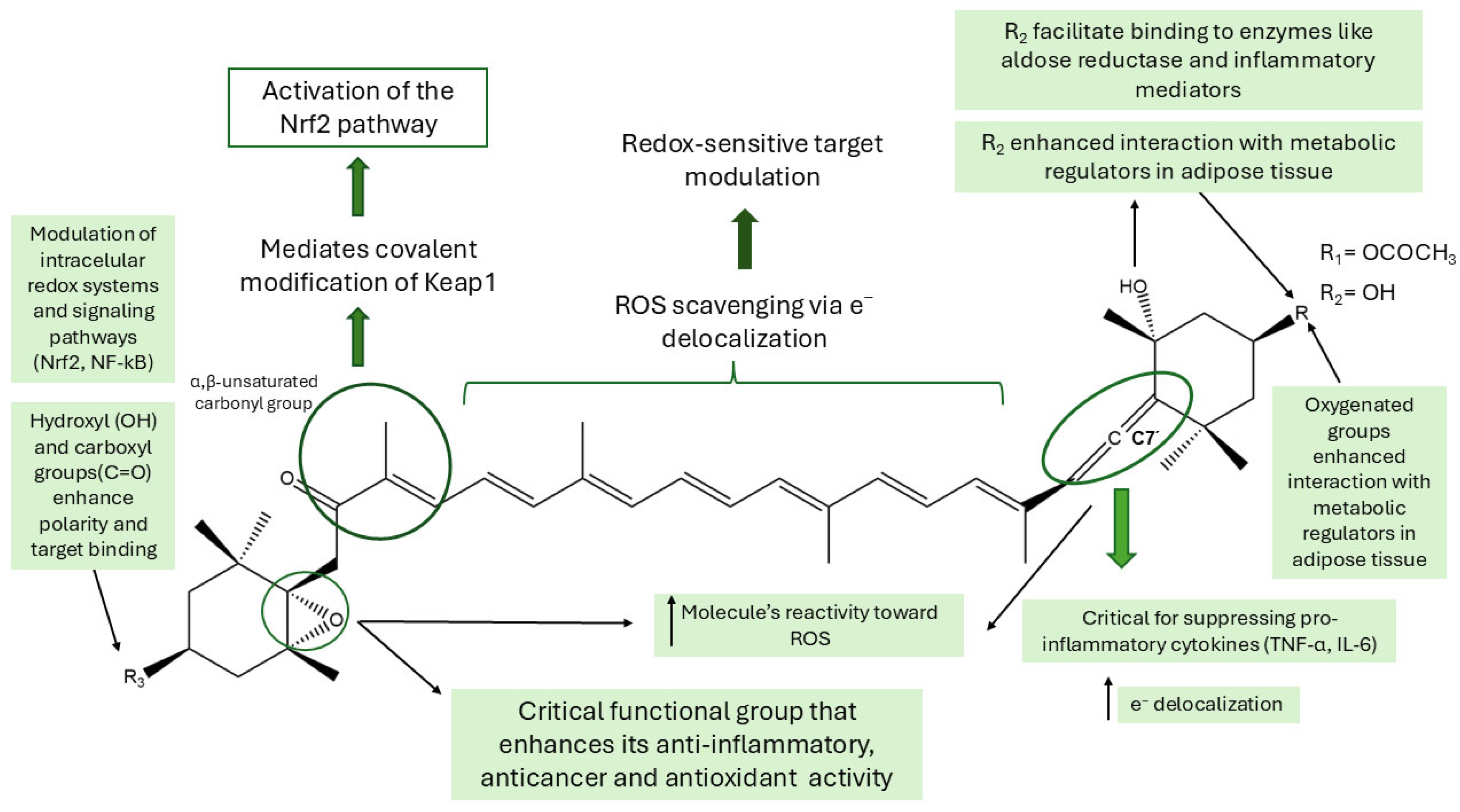

8. Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Studies

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARE | Antioxidant response elements |

| CRTISO | Carotenoid isomerase |

| CRTISO5 | Carotenoid isomerase 5 |

| Fx | Fucoxanthin |

| FxOH | Fucoxanthinol |

| GGPP | Geranylgeranyl diphosphate |

| GGPS | Geranyl pyrophosphate synthase |

| GST | Glutathione S-transferase |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase-1 |

| IPP | Isopentenyl pyrophosphate |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| LOOH | Lipid hydroperoxide |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MEP | Methylerythritol phosphate |

| MVA | Mevalonate |

| NAAA | N-acylethanolamine acid amidase |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| NIK | NF-κb-inducing kinase |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 |

| PDS | Phytoene desaturase |

| PEA | Palmitoylethanolamide |

| PPAR-α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha |

| PPAR-ϒ | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PSY | Phytoene synthase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RXR | 9-cis-retinoic acid receptor |

| SAR | Structure–activity relationship |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-α |

| UCP-1 | Uncoupling protein-1 |

| ZDS | Zeaxanthin desaturase |

| ZEP | Zeaxanthin epoxidase |

References

- Parkes, R.; Archer, L.; Gee, D.M.; Smyth, T.J.; Gillespie, E.; Touzet, N. Differential responses in EPA and fucoxanthin production by the marine diatom Stauroneis sp. under varying cultivation conditions. Biotechnol. Prog. 2021, 37, e3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruccoli, L.; Balducci, M.; Pagliarani, B.; Tarozzi, A. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Effects of Fucoxanthin and Its Metabolite Fucoxanthinol: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2024, 46, 5984–5998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.J.; Yoon, W.J.; Kim, K.N.; Ahn, G.N.; Kang, S.M.; Kang, D.H.; Affan, A.; Oh, C.; Jung, W.K.; Jeon, Y.J. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory effect of fucoxanthin isolated from brown algae in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 2045–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.H.; Shin, H.Y.; Park, J.H.; Koo, S.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Yang, S.H. Fucoxanthin from microalgae Phaeodactylum tricornutum inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines by regulating both NF-kappaB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Funayama, K.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin from edible seaweed, Undaria pinnatifida, shows antiobesity effect through UCP1 expression in white adipose tissues. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 332, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotake-Nara, E.; Terasaki, M.; Nagao, A. Characterization of apoptosis induced by fucoxanthin in human promyelocytic leukemia cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Y.; Wentao, S.; Fan, L. Progress in the Preparation and Application of Fucoxanthin from Algae. Int. J. Biol. Life Sci. 2024, 5, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, R.; Schieber, A.; Carle, R. Effects of heating and illumination on trans-cis isomerization and degradation of beta-carotene and lutein in isolated spinach chloroplasts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 9512–9518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonekura, L.; Nagao, A. Soluble fibers inhibit carotenoid micellization in vitro and uptake by Caco-2 cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikov, A.N.; Flisyuk, E.V.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Pozharitskaya, O.N. Pharmacokinetics of Marine-Derived Drugs. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco-Lopes, C.; Carreira-Casais, A.; Carperna, M.; Barral-Martinez, M.; Chamorro, F.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Cassani, L.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Prieto, M.A. Emerging Technologies to Extract Fucoxanthin from Undaria pinnatifida: Microwave vs. Ultrasound Assisted Extractions. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Jin, Y.; Hu, D.; Ye, J.; Lu, Y.; Dai, Z. One-Step Preparative Separation of Fucoxanthin from Three Edible Brown Algae by Elution-Extrusion Countercurrent Chromatography. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.L.; Jiang, Y.F.; Lu, Y.A.; Yu, J.B.; Kang, M.C.; Jeon, Y.J. Fucoxanthin-rich fraction from Sargassum fusiformis alleviates particulate matter-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Toxicol. Rep. 2021, 8, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukor, M.I.; Susanti, D.; Sabarudin, N.S.; Nor, N.M.; Taher, M. Effects of solvent extraction and drying methods of Malaysian seaweed, Sargassum polycystum on fucoxanthin content. In Proceedings of the 4th International Seminar on Chemical Education (ISCE) 2021, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 15 September 2021; AIP Publishing: Melville, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisa, A.A.; Sedjati, S.; Yudiati, E. Quantitative fucoxanthin extract of tropical Padina sp. and Sargassum sp. (Ocrophyta) and its’ radical scavenging activity. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Fisheries and Marine, North Maluku, Indonesia, 13–14 July 2020; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Xia, G.; Liu, H.; Cheng, X.; Kong, M.; Liu, Y.; Feng, C.; Chen, X.; et al. Isolation of fucoxanthin from Sargassum thunbergii and preparation of microcapsules based on palm stearin solid lipid core. Front. Mater. Sci. 2017, 11, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaswir, I.; Noviendri, D.; Salleh, H.M.; Taher, M.; Miyashita, K.; Ramli, N. Analysis of Fucoxanthin Content and Purification of All-Trans-Fucoxanthin from Turbinaria turbinata and Sargassum plagyophyllum by SiO2 Open Column Chromatography and Reversed Phase–HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2013, 36, 1340–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnett, R.; Mallams, A.K.; Spark, A.A.; Tee, J.L.; Weedon, B.C.L.; McCormick, A. Carotenoids and related compounds. Part XX. Structure and reactions of fucoxanthin. J. Chem. Soc. C Org. 1969, 3, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajauria, G.; Foley, B.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Characterization of dietary fucoxanthin from Himanthalia elongata brown seaweed. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Gao, L.; Zhao, X. Rapid Purification of Fucoxanthin from Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Molecules 2022, 27, 3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, A.; Karatas, A.B.; Demir, D.; Demirel, Z.; Akturk, M.; Copur, O.; Conk-Dalay, M. Manipulation in Culture Conditions of Nanofrustulum shiloi for Enhanced Fucoxanthin Production and Isolation by Preparative Chromatography. Molecules 2023, 28, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Sá, M.; Maia, I.; Rodrigues, A.; Teles, I.; Wijffels, R.H.; Navalho, J.; Barbosa, M. Fucoxanthin production from Tisochrysis lutea and Phaeodactylum tricornutum at industrial scale. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, M. Carotenoid biosynthesis in diatoms. Photosynth. Res. 2010, 106, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dambek, M.; Eilers, U.; Breitenbach, J.; Steiger, S.; Buchel, C.; Sandmann, G. Biosynthesis of fucoxanthin and diadinoxanthin and function of initial pathway genes in Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, B.; Ma, S.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z. Progress on the biological characteristics and physiological activities of fucoxanthin produced by marine microalgae. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1357425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilers, U.; Dietzel, L.; Breitenbach, J.; Buchel, C.; Sandmann, G. Identification of genes coding for functional zeaxanthin epoxidases in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. J. Plant Physiol. 2016, 192, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C. Brown is the new green: Discovery of an algal enzyme for the final step of fucoxanthin biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 2716–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Bai, Y.; Buschbeck, P.; Tan, Q.; Cantrell, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, R.Z.; Ries, N.K.; Shi, X.; et al. An unexpected hydratase synthesizes the green light-absorbing pigment fucoxanthin. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 3053–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 5281239, Fucoxanthin. 2025. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Fucoxanthin (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Maoka, T. Carotenoids as natural functional pigments. J. Nat. Med. 2020, 74, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosumi, D.; Kusumoto, T.; Fujii, R.; Sugisaki, M.; Iinuma, Y.; Oka, N.; Takaesu, Y.; Taira, T.; Iha, M.; Frank, H.A.; et al. One- and two-photon pump–probe optical spectroscopic measurements reveal the S1 and intramolecular charge transfer states are distinct in fucoxanthin. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 483, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achir, N.; Randrianatoandro, V.A.; Bohuon, P.; Laffargue, A.; Avallone, S. Kinetic study of β-carotene and lutein degradation in oils during heat treatment. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2010, 112, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xuan, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yan, S.; Zhou, D.; Naman, C.B.; Zhang, J.; He, S.; Yan, X.; Cui, W. Fucoxanthin has potential for therapeutic efficacy in neurodegenerative disorders by acting on multiple targets. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 25, 2167–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Ramos, A.; Gonzalez-Ortiz, M.; Martinez-Abundis, E.; Perez-Rubio, K.G. Effect of Fucoxanthin on Metabolic Syndrome, Insulin Sensitivity, and Insulin Secretion. J. Med. Food 2023, 26, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Mendonca, P.; Messeha, S.S.; Soliman, K.F.A. Anticancer Effects of Fucoxanthin through Cell Cycle Arrest, Apoptosis Induction, and Angiogenesis Inhibition in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2023, 28, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreau, D.; Tomasoni, C.; Jacquot, C.; Kaas, R.; Le Guedes, R.; Cadoret, J.P.; Muller-Feuga, A.; Kontiza, I.; Vagias, C.; Roussis, V.; et al. Cultivated microalgae and the carotenoid fucoxanthin from Odontella aurita as potent anti-proliferative agents in bronchopulmonary and epithelial cell lines. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 22, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Huang, Y.S.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K.; Hu, M.L. Inhibition of proliferation of a hepatoma cell line by fucoxanthin in relation to cell cycle arrest and enhanced gap junctional intercellular communication. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2009, 182, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.X.; Hu, X.M.; Xu, S.Q.; Jiang, Z.J.; Yang, W. Effects of fucoxanthin on proliferation and apoptosis in human gastric adenocarcinoma MGC-803 cells via JAK/STAT signal pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 657, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotake-Nara, E.; Kushiro, M.; Zhang, H.; Sugawara, T.; Miyashita, K.; Nagao, A. Carotenoids affect proliferation of human prostate cancer cells. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 3303–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.A.; Mendonca, P.; Messeha, S.S.; Oriaku, E.T.; Soliman, K.F.A. The Anticancer Effects of Marine Carotenoid Fucoxanthin through Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase (PI3K)-AKT Signaling on Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells. Molecules 2023, 29, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.F.; Wu, J.W.; Zhu, Y.S.; Hua, Z.H.; Jin, S.Z.; Ji, J.C.; Wang, C.S.; Qian, G.Y.; Jin, X.D.; Ding, H.M. Fucoxanthin Induces Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells via Downregulation of the Nrf2/HO-1/GPX4 Pathway. Molecules 2024, 29, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Hernandez, G.; Ramos-Silva, J.A.; Perez-Soto, E.; Figueroa, M.; Flores-Berrios, E.P.; Sanchez-Chapul, L.; Andrade-Cabrera, J.L.; Luna-Angulo, A.; Landa-Solis, C.; Aviles-Arnaut, H. Anticancer Activity of Plant Tocotrienols, Fucoxanthin, Fucoidan, and Polyphenols in Dietary Supplements. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Hosokawa, M.; Kasajima, H.; Hatanaka, K.; Kudo, K.; Shimoyama, N.; Miyashita, K. Anticancer effects of fucoxanthin and fucoxanthinol on colorectal cancer cell lines and colorectal cancer tissues. Oncol. Lett. 2015, 10, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, S.; Afzal, S.; Elwakeel, A.; Sharma, D.; Radhakrishnan, N.; Dhanjal, J.K.; Sundar, D.; Kaul, S.C.; Wadhwa, R. Marine Carotenoid Fucoxanthin Possesses Anti-Metastasis Activity: Molecular Evidence. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Wang, L.; Yang, K.; Wang, C. Fucoxanthin may inhibit cervical cancer cell proliferation via downregulation of HIST1H3D. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520964011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chuda, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Nagata, T. Fucoxanthin as the major antioxidant in Hijikia fusiformis, a common edible seaweed. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999, 63, 605–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Chiu, Y.T.; Hu, M.L. Fucoxanthin enhances HO-1 and NQO1 expression in murine hepatic BNL CL.2 cells through activation of the Nrf2/ARE system partially by its pro-oxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 11344–11351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.B.; Kang, H.; Li, Y.; Park, Y.K.; Lee, J.Y. Fucoxanthin inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and oxidative stress by activating nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT pathway in macrophages. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 3315–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinski, T.M.; Adamczak, A. Fucoxanthin-An Antibacterial Carotenoid. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y. Fucoxanthin Isolated from Undaria pinnatifida Can Interact with Escherichia coli and lactobacilli in the Intestine and Inhibit the Growth of Pathogenic Bacteria. J. Ocean Univ. China 2019, 18, 926–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivagnanam, S.P.; Yin, S.; Choi, J.H.; Park, Y.B.; Woo, H.C.; Chun, B.S. Biological Properties of Fucoxanthin in Oil Recovered from Two Brown Seaweeds Using Supercritical CO2 Extraction. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 3422–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, R.S.N.; Kawakami, C.M.; Pereira, K.C.; do Amaral, G.T.; Benevenuto, C.G.; Maria-Engler, S.S.; Colepicolo, P.; Debonsi, H.M.; Gaspar, L.R. Fucoxanthin for Topical Administration, a Phototoxic vs. Photoprotective Potential in a Tiered Strategy Assessed by In Vitro Methods. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urikura, I.; Sugawara, T.; Hirata, T. Protective effect of Fucoxanthin against UVB-induced skin photoaging in hairless mice. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 757–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Oh, Y.R.; Kang, E.H.; Khang, G.; Park, Y.B.; Lee, Y.J. Fucoxanthin Suppresses Osteoclastogenesis via Modulation of MAP Kinase and Nrf2 Signaling. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q.; Chen, H.; Sun, L.; Liu, G. Protective Effect of Fucoxanthin Isolated from Laminaria japonica against Visible Light-Induced Retinal Damage Both in Vitro and in Vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y. Fucoxanthin Pretreatment Ameliorates Visible Light-Induced Phagocytosis Disruption of RPE Cells under a Lipid-Rich Environment via the Nrf2 Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2021, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Tian, X.; Zhang, W.; Zheng, P.; Huang, F.; Ding, G.; Yang, Z. Protective Effects of Fucoxanthin against Alcoholic Liver Injury by Activation of Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Defense and Inhibition of TLR4-Mediated Inflammation. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, S.Y.; Hwang, J.H.; Yang, S.H.; Um, J.I.; Hong, K.W.; Kang, K.; Pan, C.H.; Hwang, K.T.; Kim, S.M. Anti-Obesity Effect of Standardized Extract of Microalga Phaeodactylum tricornutum Containing Fucoxanthin. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Kanno, S.; Kodate, M.; Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthinol, Metabolite of Fucoxanthin, Improves Obesity-Induced Inflammation in Adipocyte Cells. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 4799–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Miyashita, K. Dietary combination of fucoxanthin and fish oil attenuates the weight gain of white adipose tissue and decreases blood glucose in obese/diabetic KK-Ay mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7701–7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lee, M.K.; Park, Y.B.; Shin, Y.C.; Choi, M.S. Beneficial effects of Undaria pinnatifida ethanol extract on diet-induced-insulin resistance in C57BL/6J mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Guo, K.; Huang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Li, D.; Pang, K.L.; Wang, G.; Chen, L.; et al. Fucoxanthin, a Marine Xanthophyll Isolated From Conticribra weissflogii ND-8: Preventive Anti-Inflammatory Effect in a Mouse Model of Sepsis. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyashita, K.; Hosokawa, M. Fucoxanthin in the management of obesity and its related disorders. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 36, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, T.; Baskaran, V.; Tsuzuki, W.; Nagao, A. Brown algae fucoxanthin is hydrolyzed to fucoxanthinol during absorption by Caco-2 human intestinal cells and mice. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 946–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, T.; Ozaki, Y.; Taminato, M.; Das, S.K.; Mizuno, M.; Yoshimura, K.; Maoka, T.; Kanazawa, K. The distribution and accumulation of fucoxanthin and its metabolites after oral administration in mice. Br. J. Nutr. 2009, 102, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asai, A.; Sugawara, T.; Ono, H.; Nagao, A. Biotransformation of fucoxanthinol into amarouciaxanthin A in mice and HepG2 cells: Formation and cytotoxicity of fucoxanthin metabolites. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004, 32, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, B.; Oliviero, T.; Fogliano, V.; Ma, Y.; Chen, F.; Capuano, E. Gastrointestinal Bioaccessibility and Colonic Fermentation of Fucoxanthin from the Extract of the Microalga Nitzschia laevis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1844–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Qu, J.; Wang, X.; Kong, R.; Han, C.; Liu, Z. Fucoxanthin: A Promising Medicinal and Nutritional Ingredient. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 2015, 723515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viera, I.; Perez-Galvez, A.; Roca, M. Bioaccessibility of Marine Carotenoids. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, E.J.; Ham, Y.M.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.G. Anti-inflammatory effects of apo-9’-fucoxanthinone from the brown alga, Sargassum muticum. Daru 2013, 21, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Chand, H.S.; Lee, J.S.; Lin, Y.; Weathington, N.; Mallampalli, R.; Jeon, Y.J.; Nyunoya, T. APO-9’-Fucoxanthinone Extracted from Undariopsis peteseniana Protects Oxidative Stress-Mediated Apoptosis in Cigarette Smoke-Exposed Human Airway Epithelial Cells. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komba, S.; Kotake-Nara, E.; Tsuzuki, W. Degradation of Fucoxanthin to Elucidate the Relationship between the Fucoxanthin Molecular Structure and Its Antiproliferative Effect on Caco-2 Cells. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repeta, D.J. Carotenoid diagenesis in recent marine sediments: II. Degradation of fucoxanthin to loliolide. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.N.; Nabende, W.Y.; Jeong, H.; Hahn, D.; Jeong, G.S. The Marine-Derived Natural Product Epiloliolide Isolated from Sargassum horneri Regulates NLRP3 via PKA/CREB, Promoting Proliferation and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Human Periodontal Ligament Cells. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayawardena, T.U.; Kim, H.-S.; Asanka Sanjeewa, K.K.; Han, E.J.; Jee, Y.; Ahn, G.; Rho, J.-R.; Jeon, Y.-J. Loliolide, isolated from Sargassum horneri; abate LPS-induced inflammation via TLR mediated NF-κB, MAPK pathways in macrophages. Algal Res. 2021, 56, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.H.; Yun, J.H.; Heo, J.; Lee, I.K.; Lee, Y.J.; Bae, S.; Yun, B.S.; Kim, H.S. Identification of Loliolide with Anti-Aging Properties from Scenedesmus deserticola JD052. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 1250–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoka, T.; Nishino, A.; Yasui, H.; Yamano, Y.; Wada, A. Anti-Oxidative Activity of Mytiloxanthin, a Metabolite of Fucoxanthin in Shellfish and Tunicates. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokkaku, T.; Kimura, R.; Ishikawa, C.; Yasumoto, T.; Senba, M.; Kanaya, F.; Mori, N. Anticancer effects of marine carotenoids, fucoxanthin and its deacetylated product, fucoxanthinol, on osteosarcoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwigemera, A.; Mamelona, J.; Martin, L.J. Inhibitory effects of fucoxanthinol on the viability of human breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 are correlated with modulation of the NF-kappaB pathway. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2014, 30, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwigemera, A.; Mamelona, J.; Martin, L.J. Comparative effects between fucoxanthinol and its precursor fucoxanthin on viability and apoptosis of breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231. Anticancer Res. 2015, 35, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Konishi, I.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Miyashita, K. Halocynthiaxanthin and fucoxanthinol isolated from Halocynthia roretzi induce apoptosis in human leukemia, breast and colon cancer cells. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2006, 142, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, M.; Maeda, H.; Miyashita, K.; Mutoh, M. Induction of Anoikis in Human Colorectal Cancer Cells by Fucoxanthinol. Nutr. Cancer 2017, 69, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.; Narita, T.; Fujii, G.; Miyamoto, S.; Hamoya, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Takahashi, M.; Miki, K.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Komiya, M.; et al. Inhibition of NF-kappaB transcriptional activity enhances fucoxanthinol-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells. Genes Environ. 2019, 41, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafuku, S.; Ishikawa, C.; Yasumoto, T.; Mori, N. Anti-neoplastic effects of fucoxanthin and its deacetylated product, fucoxanthinol, on Burkitt’s and Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2012, 28, 1512–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Takahashi, N.; Kawada, T.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin and its metabolite, fucoxanthinol, suppress adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2006, 18, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Yang, L.; Yi, Z.; Fang, H.; Chen, W.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, L. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Fucoxanthinol in LPS-Induced RAW264.7 Cells through the NAAA-PEA Pathway. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, M.; Miyashita, T.; Nishikawa, S.; Emi, S.; Tsukui, T.; Beppu, F.; Okada, T.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin regulates adipocytokine mRNA expression in white adipose tissue of diabetic/obese KK-Ay mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010, 504, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takatani, N.; Kono, Y.; Beppu, F.; Okamatsu-Ogura, Y.; Yamano, Y.; Miyashita, K.; Hosokawa, M. Fucoxanthin inhibits hepatic oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 528, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Sun, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Sun, H.; Cheng, K.W.; Chen, F. Fucoxanthinol from the Diatom Nitzschia Laevis Ameliorates Neuroinflammatory Responses in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV-2 Microglia. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, D.; Manzoor, Z.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, S.; Oh, T.H.; Yoo, E.S.; Kang, H.K.; Hyun, J.W.; Lee, N.H.; Ko, M.H.; et al. Apo-9’-fucoxanthinone, isolated from Sargassum muticum, inhibits CpG-induced inflammatory response by attenuating the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 3272–3287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.A.; Kim, S.Y.; Ye, B.R.; Kim, J.; Ko, S.C.; Lee, W.W.; Kim, K.N.; Choi, I.W.; Jung, W.K.; Heo, S.J. Anti-inflammatory effect of Apo-9’-fucoxanthinone via inhibition of MAPKs and NF-kB signaling pathway in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages and zebrafish model. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2018, 59, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-S.; Fernando, I.P.S.; Lee, S.-H.; Ko, S.-C.; Kang, M.C.; Ahn, G.; Je, J.-G.; Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Rho, J.-R.; Shin, H.J.; et al. Isolation and characterization of anti-inflammatory compounds from Sargassum horneri via high-performance centrifugal partition chromatography and high-performance liquid chromatography. Algal Res. 2021, 54, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naugler, W.E.; Karin, M. NF-kappaB and cancer-identifying targets and mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2008, 18, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Motohashi, H. The KEAP1-NRF2 System: A Thiol-Based Sensor-Effector Apparatus for Maintaining Redox Homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, L.; Yamamoto, M. The Molecular Mechanisms Regulating the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 40, e00099-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersten, S. Integrated physiology and systems biology of PPARalpha. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, M.; Lefebvre, P.; Staels, B. Molecular mechanism of PPARalpha action and its impact on lipid metabolism, inflammation and fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, Y.; Shen, S.; Verma, I.M. NF-kappaB, an active player in human cancers. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014, 2, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 2000, 100, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, H. NF-kappaB signaling in inflammation and cancer. MedComm 2021, 2, 618–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavitra, E.; Kancharla, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Prasad, K.; Sung, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Tej, M.B.; Choi, R.; Lee, J.H.; Han, Y.K.; et al. The role of NF-kappaB in breast cancer initiation, growth, metastasis, and resistance to chemotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Ru, X.; Wen, T. NRF2, a Transcription Factor for Stress Response and Beyond. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Hu, Y. Insight into Nrf2: A bibliometric and visual analysis from 2000 to 2022. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1266680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Wu, Q.; Lu, F.; Lei, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, N.; Yu, Y.; Ning, Z.; She, T.; et al. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Current status and potential therapeutic targetable role in human cancers. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1184079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.M.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, E.H.; Suzuki, T.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Hayashi, M.; Sekine, H.; Tanaka, N.; Moriguchi, T.; Motohashi, H.; Nakayama, K.; et al. Nrf2 suppresses macrophage inflammatory response by blocking proinflammatory cytokine transcription. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuadrado, A.; Rojo, A.I.; Wells, G.; Hayes, J.D.; Cousin, S.P.; Rumsey, W.L.; Attucks, O.C.; Franklin, S.; Levonen, A.L.; Kensler, T.W.; et al. Therapeutic targeting of the NRF2 and KEAP1 partnership in chronic diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yuan, T.; Li, L.; Nahar, P.; Slitt, A.; Seeram, N.P. Chemical compositional, biological, and safety studies of a novel maple syrup derived extract for nutraceutical applications. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6687–6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornak, P.; Kottfer, D.; Kyziol, K.; Trebunova, M.; Majernikova, J.; Kaczmarek, L.; Trebuna, J.; Hasul, J.; Palo, M. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Annealed WC/C PECVD Coatings Deposited Using Hexacarbonyl of W with Different Gases. Materials 2020, 13, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, S.; Gupta, P.; Saini, A.S.; Kaushal, C.; Sharma, S. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor: A family of nuclear receptors role in various diseases. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2011, 2, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willson, T.M.; Lambert, M.H.; Kliewer, S.A. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and metabolic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001, 70, 341–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yessoufou, A.; Wahli, W. Multifaceted roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) at the cellular and whole organism levels. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2010, 140, w13071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygiel-Gorniak, B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: Nutritional and clinical implications—A review. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroker, A.J.; Bruning, J.B. Review of the Structural and Dynamic Mechanisms of PPARgamma Partial Agonism. PPAR Res. 2015, 2015, 816856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, E.; Guzman-Jofre, L.; Moore-Carrasco, R.; Palomo, I. Role of PPARs in inflammatory processes associated with metabolic syndrome (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2013, 8, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corzo, C.; Griffin, P.R. Targeting the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-gamma to Counter the Inflammatory Milieu in Obesity. Diabetes Metab. J. 2013, 37, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panuganti, K.K.; Minhthao, N.; Kshirsagar, R.K.; Doerr, C. Obesity; StatPearls: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Scully, T.; Ettela, A.; LeRoith, D.; Gallagher, E.J. Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and Cancer Risk. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 615375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piche, M.E.; Tchernof, A.; Despres, J.P. Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126, 1477–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belladelli, F.; Montorsi, F.; Martini, A. Metabolic syndrome, obesity and cancer risk. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2022, 32, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Obesity Federation. World Obesity Atlas 2025; World Obesity Federation: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello, C.A. Anti-inflammatory Agents: Present and Future. Cell 2010, 140, 935–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahima, R.S.; Lazar, M.A. Adipokines and the peripheral and neural control of energy balance. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, B.; Sultana, R.; Greene, M.W. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 137, 111315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, S.P.; McCann, D.; Desai, M.; Rosenbaum, M.; Leibel, R.L.; Ferrante, A.W., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1796–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinti, S.; Mitchell, G.; Barbatelli, G.; Murano, I.; Ceresi, E.; Faloia, E.; Wang, S.; Fortier, M.; Greenberg, A.S.; Obin, M.S. Adipocyte death defines macrophage localization and function in adipose tissue of obese mice and humans. J. Lipid Res. 2005, 46, 2347–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Barnes, G.T.; Yang, Q.; Tan, G.; Yang, D.; Chou, C.J.; Sole, J.; Nichols, A.; Ross, J.S.; Tartaglia, L.A.; et al. Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2003, 112, 1821–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Kokoeva, M.V.; Inouye, K.; Tzameli, I.; Yin, H.; Flier, J.S. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamano, Y.; Tode, C.; Ito, M. Carotenoids and related polyenes. Part 3. First total synthesis of fucoxanthin and halocynthiaxanthin using oxo-metallic catalyst. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1 1995, 15, 1895–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajikawa, T.; Okumura, S.; Iwashita, T.; Kosumi, D.; Hashimoto, H.; Katsumura, S. Stereocontrolled total synthesis of fucoxanthin and its polyene chain-modified derivative. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 808–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenco-Lopes, C.; Garcia-Oliveira, P.; Carpena, M.; Fraga-Corral, M.; Jimenez-Lopez, C.; Pereira, A.G.; Prieto, M.A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Scientific Approaches on Extraction, Purification and Stability for the Commercialization of Fucoxanthin Recovered from Brown Algae. Foods 2020, 9, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budiarso, F.S.; Leong, Y.K.; Chang, J.J.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, J.H.; Yen, H.W.; Chang, J.S. Current advances in microalgae-based fucoxanthin production and downstream processes. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 428, 132455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.D.; Pan, C.H. Strategies for the Total Synthesis of Fucoxanthin from a Commercial Perspective. SynOpen 2024, 8, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J.; Tsukamoto, M.; Yanai, Y.; Liu, S.; Manabe, Y.; Sugawara, T. Anti-obesity Activity of Alkali-treated Fucoxanthin in C57BL6J Mice Fed a High-Fat Diet. Trace Nutr. Res. 2024, 41, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Komba, S.; Kotake-Nara, E.; Machida, S. Fucoxanthin Derivatives: Synthesis and their Chemical Properties. J. Oleo Sci. 2015, 64, 1009–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T. Fucoxanthin extract ameliorates obesity associated with modulation of bile acid metabolism and gut microbiota in high-fat-diet fed mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2024, 63, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; D’Orazio, N. Anti-obesity activity of the marine carotenoid fucoxanthin. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2196–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wang, K.; Wan, L.; Li, A.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, C. Production, characterization, and antioxidant activity of fucoxanthin from the marine diatom Odontella aurita. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 2667–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyashita, K.; Nishikawa, S.; Beppu, F.; Tsukui, T.; Abe, M.; Hosokawa, M. The allenic carotenoid fucoxanthin, a novel marine nutraceutical from brown seaweeds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2011, 91, 1166–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.J.; Jeon, Y.J. Protective effect of fucoxanthin isolated from Sargassum siliquastrum on UV-B induced cell damage. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2009, 95, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yuan, J.P.; Wu, C.F.; Wang, J.H. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid present in brown seaweeds and diatoms: Metabolism and bioactivities relevant to human health. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1806–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Murakami-Funayama, K.; Miyashita, K. Anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects of fucoxanthin on diet-induced obesity conditions in a murine model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2009, 2, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazio, N.; Gammone, M.A.; Gemello, E.; De Girolamo, M.; Cusenza, S.; Riccioni, G. Marine bioactives: Pharmacological properties and potential applications against inflammatory diseases. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 812–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiratori, K.; Ohgami, K.; Ilieva, I.; Jin, X.H.; Koyama, Y.; Miyashita, K.; Yoshida, K.; Kase, S.; Ohno, S. Effects of fucoxanthin on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Eye Res. 2005, 81, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Ishikawa, C.; Katano, H.; Yasumoto, T.; Mori, N. Fucoxanthin and its deacetylated product, fucoxanthinol, induce apoptosis of primary effusion lymphomas. Cancer Lett. 2011, 300, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duitsman, P.K.; Barua, A.B.; Becker, B.; Olson, J.A. Effects of epoxycarotenoids, beta-carotene, and retinoic acid on the differentiation and viability of the leukemia cell line NB4 in vitro. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1999, 69, 303–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, M.; Kudo, M.; Maeda, H.; Kohno, H.; Tanaka, T.; Miyashita, K. Fucoxanthin induces apoptosis and enhances the antiproliferative effect of the PPARgamma ligand, troglitazone, on colon cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1675, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taira, J.; Sonamoto, M.; Uehara, M. Dual Biological Functions of a Cytoprotective Effect and Apoptosis Induction by Bioavailable Marine Carotenoid Fucoxanthinol through Modulation of the Nrf2 Activation in RAW264.7 Macrophage Cells. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taira, J.; Kubo, T.; Nagano, H.; Tsuda, R.; Ogi, T.; Nakashima, K.; Suzuki, T. Effect of Nrf2 Activators in Hepatitis B Virus-Infected Cells Under Oxidative Stress. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Compound Type | Bioactivity | Model (Cell Line) | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fucoxanthinol (FxOH) | Metabolite | Anticancer | Saos-2 | Induces apoptosis through activation of caspases-3,-8 and 9 [78] Inhibits cell viability [78] Inhibits cell migration and invasion [78] Inhibits AP-1 activation [78] |

| MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | Inhibits viability in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells [79,80] Induces apoptosis in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 (increased Annexin V signal) [79,80] Reduces SOX9 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells [80] Decreases levels of necrosis [80] Inhibits nuclear accumulation of NF-κB components (p65, p52, RelB) in MDA-MB-231 cells [79,80] Induces DNA fragmentation in MCF-7 cells [81] | |||

| DLD-1 | Induces anoikis [82] Inhibits EMT [82] | |||

| HCT116 and HT-29 | Induces apoptosis via NF-κB inhibition and IAP suppression [83] | |||

| Caco-2 SW620 DLD-1 WiDr | Reduces cell viability [43,81] Induces DNA fragmentation [81] | |||

| HL-60 | Reduces cell viability [81] Induces apoptosis, chromatin condensation and nuclear degradation (DNA damage) [81] Reduces Bcl-2 protein levels [81] | |||

| Raji Daubi BJAB Ramos BJAB L428 KM-H2 HDLM-2 L540 | Reduces cell viability [84] Causes G1 cell cycle arrest [84] Induces apoptosis [84] | |||

| Anti-obesity | 3T3-L1 | Down-regulates PPARϒ [59,85] | ||

| Anti-Inflammatory | RAW264.7 3T3-F442A Hepa-1-6 cells | Reduces production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β and NO [59,86,87,88] | ||

| BV-2 | Inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory mediators (iNOs, NO, PGE-2 and COX-2) [89] | |||

| Antioxidant | SH-SY5Y | Reduces ROS formation [2] Increases intracellular GSH through the Nrf2/Keap1/ARE pathway [2] | ||

| Neuroprotective | SH-SY5Y | Preserves neuronal protection against toxicity caused by AβO and 6-OHDA [2] | ||

| Halocynthiaxanthin | Metabolite | Anticancer | HL-60 | Reduces cell viability [81] Induces apoptosis, chromatin condensation and nuclear degradation (DNA damage) [81] Reduces Bcl-2 protein levels [81] |

| MCF-7 | Reduces cell viability [81] Induces DNA fragmentation [81] | |||

| Caco-2 cells | Reduces cell viability [81] Induces DNA fragmentation [81] | |||

| Amarouciaxanthin A | Metabolite | Anti-inflammatory | Hepa-1-6 cells | Suppresses chemokine production in TNFα-stimulated liver cells [88] |

| Apo-9′-fucoxanthinone (1) | Derivative | Anti-inflammatory | BMDMs and BMDCs RAW 264.7 | Inhibits production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-12 p40, IL-6 e TNF-α) and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in macrophages and dendritic cells [90] NO/iNOS/COX-2 regulation, inhibition of NF-κB and JNK/ERK pathways in zebrafish and RAW 264.7 cells [91] |

| Anticancer | Caco-2 cells HBEC2 cells | Inhibits cell proliferation [72] Reduces oxidative stress, DNA damage, and chronic inflammation [71] | ||

| Apo-13-fucoxanthinone (2) | Derivative | Anticancer | Caco-2 cells | Exhibits antiproliferative effects on cancer cells (lower compared to other fucoxanthin derivatives such as apo-9′-fucoxanthinone) [71] |

| 3-hydroxy-DHA (loliolide) (3) | Derivative | Anti-inflammatory | RAW 264.7 | Suppresses NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells [92] Supresses IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, PGE2 COX-2, and iNOS production in LPS-induced cells [75] |

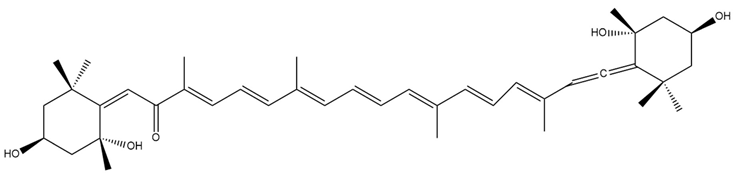

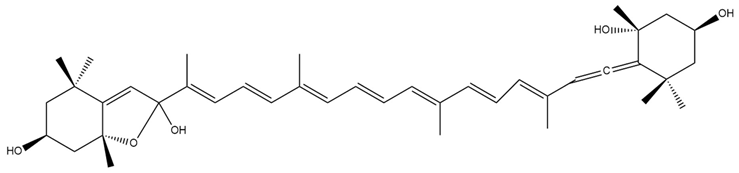

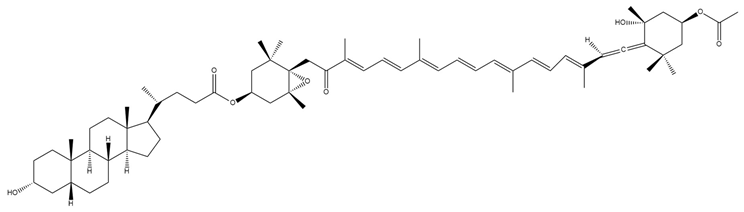

| Compound | Structure | Origin | Experimental Model | Observed/Predicted Activity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isofucoxanthinol (4) |  | Semi-synthetic | C57BL/6JmsSlc | Observed trend toward reduced body weight and adipose tissue in mice (dietary administration) [139] |

| Fucoxanthinol hemiketal (5) |  | Semi-synthetic | C57BL/6JmsSlc | Observed trend toward reduced body weight and adipose tissue in mice (dietary administration) [139] |

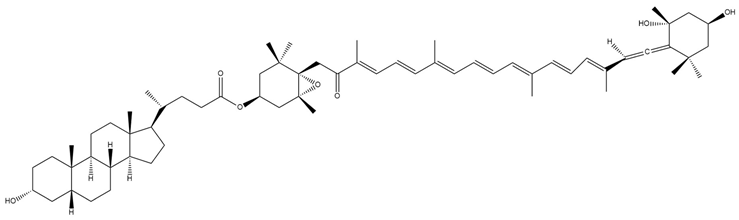

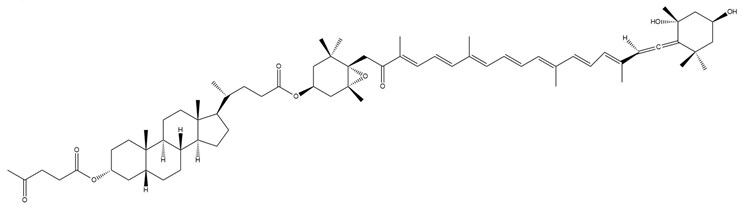

| Lithocholylfucoxanthin (6) |  | Semi-synthetic | Caco-2 cells | Predicted stronger chemoprotective, anticancer, and antiproliferative activity vs. Fx and FxOH (PASS analysis) [140] |

| Lithocholyl-fucoxanthinol (7) |  | Semi-synthetic | Caco-2 cells | Predicted stronger chemoprotective, anticancer, and antiproliferative activity vs. Fx and FxOH (PASS analysis) [140] |

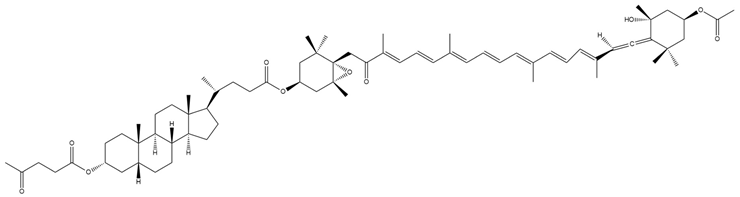

| Lithocholylfucoxanthin levulinate (8) |  | Semi-synthetic | Caco-2 cells | Predicted stronger chemoprotective, anticancer, and antiproliferative activity than Fx and FxOH (PASS analysis) [140] |

| Lev-lithocholilfucoxanthinol (9) |  | Semi-synthetic | Caco-2 cells | Predicted stronger chemoprotective, anticancer, and antiproliferative activity than Fx and FxOH; similar anti-obesity potential to Fx (PASS analysis) [140] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nogueira, P.; Bombarda-Rocha, V.; Tavares-Henriques, R.; Carneiro, M.; Sousa, E.; Gonçalves, J.; Fresco, P. Structure Meets Function: Dissecting Fucoxanthin’s Bioactive Architecture. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23, 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110440

Nogueira P, Bombarda-Rocha V, Tavares-Henriques R, Carneiro M, Sousa E, Gonçalves J, Fresco P. Structure Meets Function: Dissecting Fucoxanthin’s Bioactive Architecture. Marine Drugs. 2025; 23(11):440. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110440

Chicago/Turabian StyleNogueira, Patrícia, Victória Bombarda-Rocha, Rita Tavares-Henriques, Mariana Carneiro, Emília Sousa, Jorge Gonçalves, and Paula Fresco. 2025. "Structure Meets Function: Dissecting Fucoxanthin’s Bioactive Architecture" Marine Drugs 23, no. 11: 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110440

APA StyleNogueira, P., Bombarda-Rocha, V., Tavares-Henriques, R., Carneiro, M., Sousa, E., Gonçalves, J., & Fresco, P. (2025). Structure Meets Function: Dissecting Fucoxanthin’s Bioactive Architecture. Marine Drugs, 23(11), 440. https://doi.org/10.3390/md23110440