Synthesis of Marine (−)-Pelorol and Future Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

2.1. Andersen’s Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

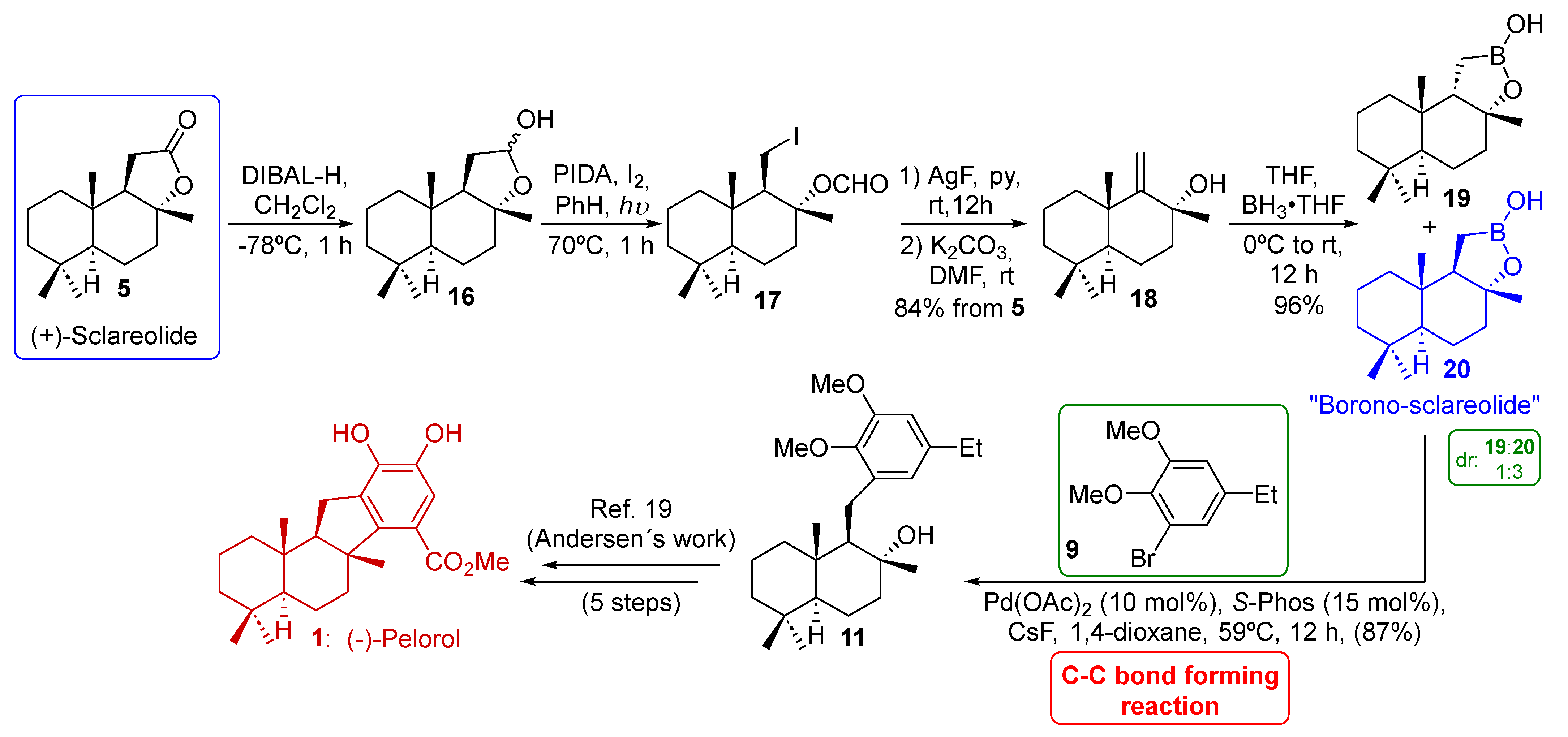

2.2. Baran’s Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

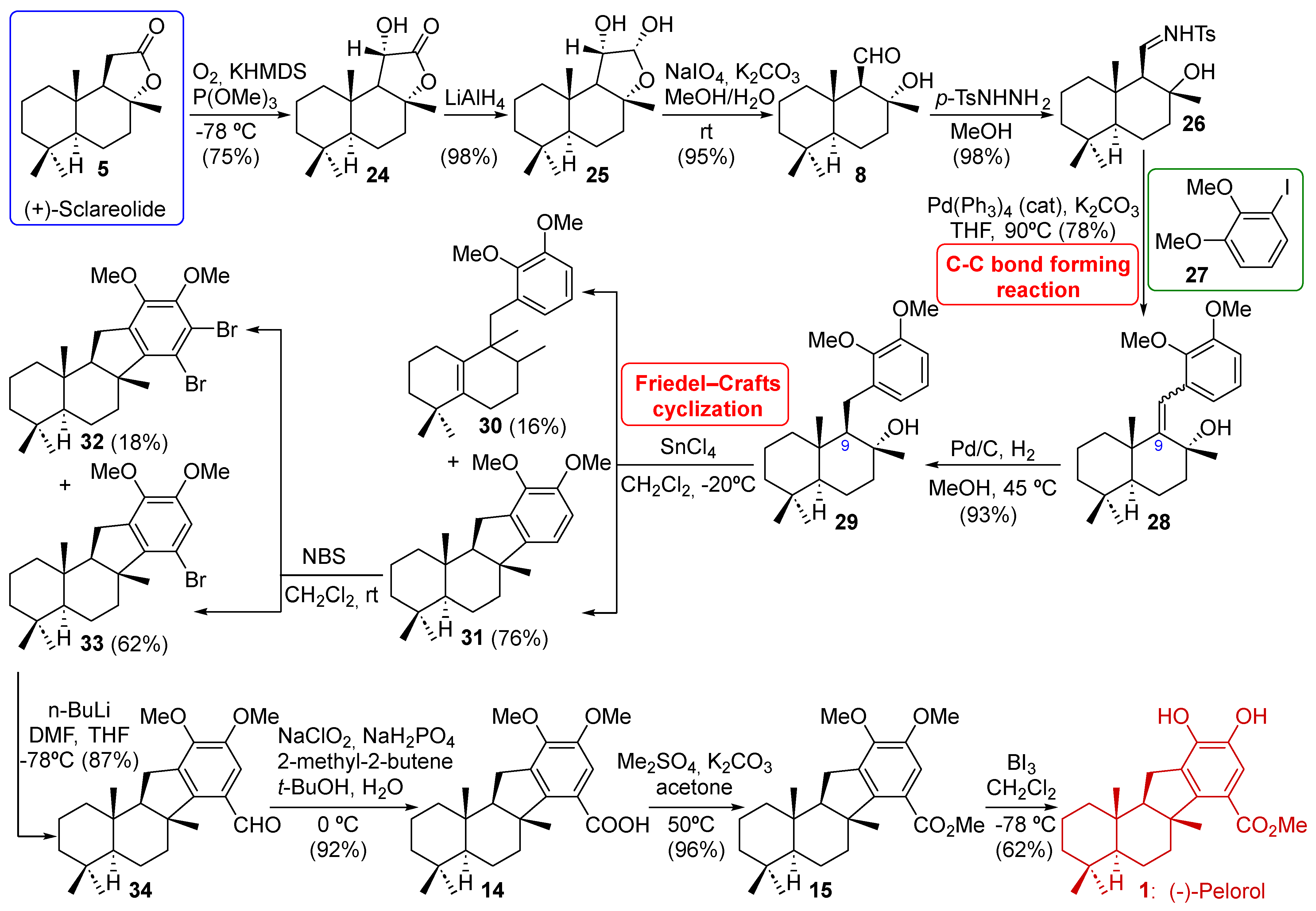

2.3. Lu’s Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

2.4. Wu’s Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

2.5. Li’s Synthesis of (−)-Pelorol (1)

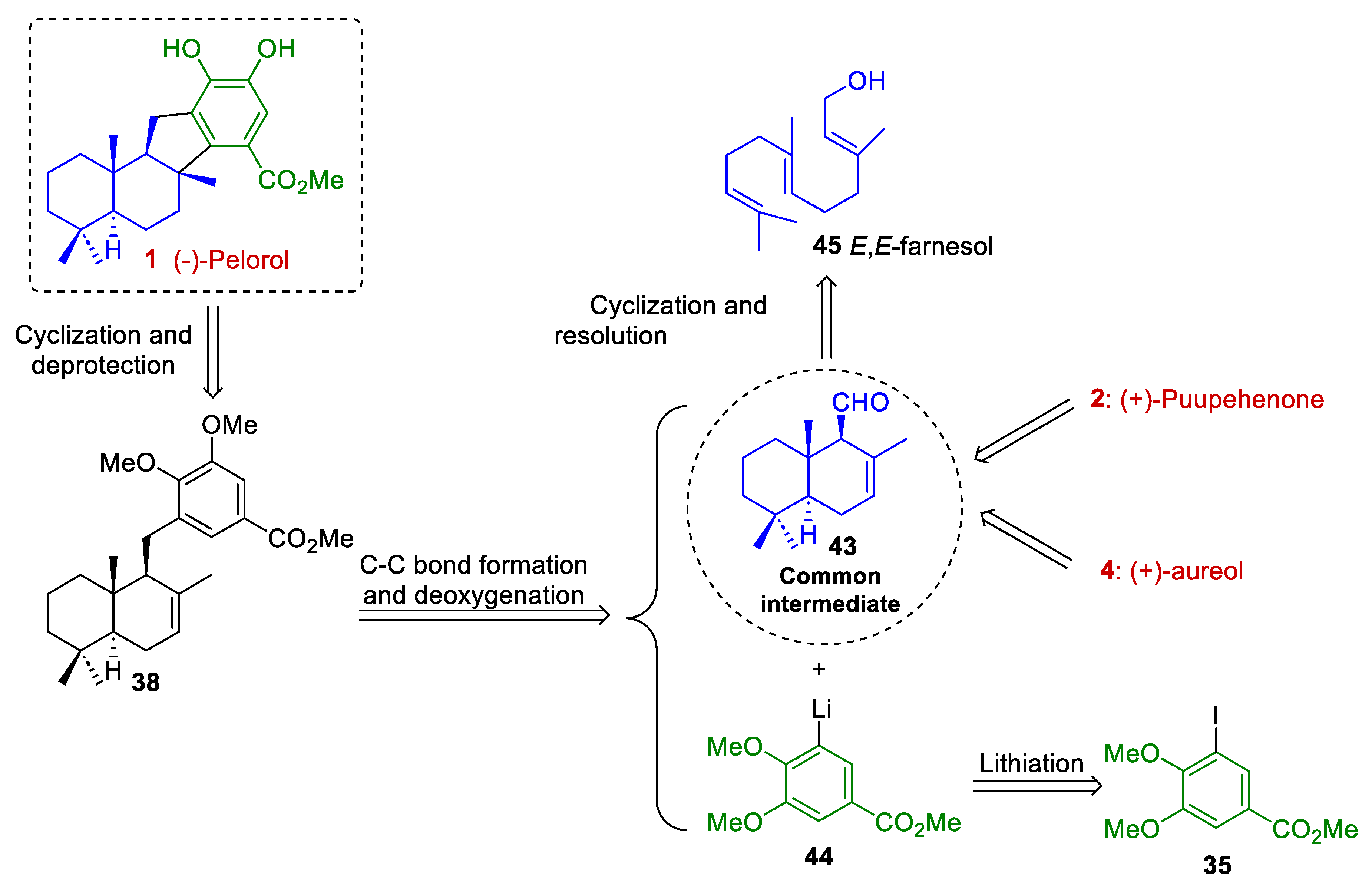

3. Future Perspectives

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Geris, R.; Simpson, T.J. Meroterpenoids produced by fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2009, 26, 1063–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomm, A.; Nelson, A. A radical approach to diverse meroterpenoids. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, M.; Saleem, M.; Tousif, M.I.; Anwar, M.A.; Surup, F.; Ali, I.; Wang, D.; Mamadalieva, N.Z.; Alshammari, E.; Ashour, M.L.; et al. Meroterpenoids: A Comprehensive Update Insight on Structural Diversity and Biology. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcos, I.S.; Conde, A.; Moro, R.F.; Basabe, P.; Diez, D.; Urones, J.G. Quinone/Hydroquinone Sesquiterpenes. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2010, 7, 230–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menna, M.; Imperatore, C.; D’Aniello, F.; Aiello, A. Meroterpenes from Marine Invertebrates: Structures, Occurrence, and Ecological Implications. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 1602–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.A.; Hernández, Á.P.; San Feliciano, A.; Castro, M.Á. Bioactive Prenyl- and Terpenyl-Quinones/Hydroquinones of Marine Origin. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sayed, K.A.; Bartyzel, P.; Shen, X.; Perry, T.L.; Zjawiony, J.K.; Hamann, M.T. Marine Natural Products as Antituberculosis Agents. Tetrahedron 2000, 56, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasu, S.S.; Yeung, B.K.S.; Hamann, M.T.; Scheuer, P.J.; Kelly-Borges, M.; Goins, K. Puupehenone-related metabolites from two Hawaiian sponges, Hyrtios spp. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 7290–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña, I.C.; Sanders, M.L.; Crews, P. Puupehenone Congeners from an Indo-Pacific Hyrtios Sponge. J. Nat. Prod. 2003, 66, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longley, R.E.; McConnell, O.J.; Essich, E.; Harmody, D. Evaluation of Marine Sponge Metabolites for Cytotoxicity and Signal Transduction Activity. J. Nat. Prod. 1993, 56, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.E.; Gonzalez-Iriarte, M.; Barrero, A.F.; Salvador-Tormo, N.; Munoz-Chapuli, R.; Medina, M.A.; Quesada, A.R. Study of puupehenone and related compounds as inhibitors of angiogenesis. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 110, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, D.J. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1998, 15, 113–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Pal, M.; Sharma, R.P. Biological Activity of the Labdane Diterpenes. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Chen, C.-H.; Liaw, C.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Shen, Y.-C. Cembrane diterpenoids from the Taiwanese soft coral Sinularia flexibilis. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 9157–9164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goclik, E.; König, G.M.; Wright, A.D.; Kaminsky, R. Pelorol from the Tropical Marine Sponge Dactylospongia elegans. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1150–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, J.H.; Schmitz, F.J.; Kelly, M. Sesquiterpene Quinols/Quinones from the Micronesian Sponge Petrosaspongia metachromia. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, E.; Latif, A.; Kong, C.-S.; Seo, Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Dalal, S.R.; Cassera, M.B.; Kingston, D.G.I. Antimalarial activity of the isolates from the marine sponge Hyrtios erectus against the chloroquine-resistant Dd2 strain of Plasmodium falciparum. Z. Naturforsch. C Biosci. 2018, 73, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpi, S.; Scoditti, E.; Polini, B.; Brogi, S.; Calderone, V.; Proksch, P.; Ebada, S.S.; Nieri, P. Pro-Apoptotic Activity of the Marine Sponge Dactylospongia elegans Metabolites Pelorol and 5-epi-Ilimaquinone on Human 501Mel Melanoma Cells. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Williams, D.E.; Mui, A.; Ong, C.; Krystal, G.; van Soest, R.; Andersen, R.J. Synthesis of Pelorol and Analogues: Activators of the Inositol 5-Phosphatase SHIP. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1073–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; He, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Li, S. Facile Synthesis and First Antifungal Exploration of Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids: (+)-Aureol, (−)-Pelorol, and Its Analogs. J. Nat. Prod. 2024, 87, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Chen, H.; Weng, J.; Lu, G. Synthesis of Pelorol and Its Analogs and Their Inhibitory Effects on Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-García, I.; López-Martínez, J.L. Divergent Strategy in Marine Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids Synthesis. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meimetis, L.G.; Nodwell, M.; Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Mui, A.L.; Ong, C.; Krystal, G.; Andersen, R.J. Development of SHIP activators: Potentially selective cancer therapy. In Proceedings of the 240th ACS National Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 22–26 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, D.D.; Lockner, J.W.; Zhou, Q.; Baran, P.S. Scalable, Divergent Synthesis of Meroterpenoids via “Borono-sclareolide”. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8432–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-S.; Nan, X.; Li, H.-J.; Cao, Z.-Y.; Wu, Y.-C. A modular strategy for the synthesis of marine originated meroterpenoid-type natural products. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2021, 19, 9439–9447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-F.; Li, H.-J.; Wang, X.-B.; Wu, Y.-C. Concise synthesis of marine natural products smenodiol and (−)-pelorol. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concepción, J.I.; Francisco, C.G.; Freire, R.; Hernandez, R.; Salazar, J.A.; Suarez, E. Iodosobenzene diacetate, an efficient reagent for the oxidative decarboxylation of carboxylic acids. J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51, 402–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barluenga, J.; Moriel, P.; Valdés, C.; Aznar, F. N-Tosylhydrazones as Reagents for Cross-Coupling Reactions: A Route to Polysubstituted Olefins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5587–5590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakde, B.N.; Kumar, N.; Mondal, P.K.; Bisai, A. Approach to Merosesquiterpenes via Lewis Acid Catalyzed Nazarov-Type Cyclization: Total Synthesis of Akaol A. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 1752–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gansäuer, A.; Justicia, J.; Rosales, A.; Worgull, D.; Rinker, B.; Cuerva, J.M.; Oltra, J.E. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Allylic Substitution and Titanocene-Catalyzed Epoxypolyene Cyclization as a Powerful Tool for the Preparation of Terpenoids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 2006, 4115–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; López-Sánchez, C.; Alvarez-Corral, M.; Muñoz-Dorado, M.; Rodríguez-García, I. Total Synthesis of (±)-Euryfuran Through Ti(III) Catalyzed Radical Cyclization. Lett. Org. Chem. 2007, 4, 553–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Muñoz-Bascón, J.; Morales-Alcázar, V.M.; Castilla-Alcalá, J.A.; Oltra, J.E. Ti(III)-Catalyzed, concise synthesis of marine furanospongian diterpenes. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 12922–12925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Muñoz-Bascón, J.; López-Sánchez, C.; Álvarez-Corral, M.; Muñoz-Dorado, M.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Oltra, J.E. Ti-Catalyzed Homolytic Opening of Ozonides: A Sustainable C–C Bond-Forming Reaction. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 4171–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, A.; Foley, L.A.R.; Padial, N.M.; Muñoz-Bascón, J.; Sancho-Sanz, I.; Roldan-Molina, E.; Pozo-Morales, L.; Irías-Álvarez, A.; Rodríguez-Maecker, R.; Rodríguez-García, I.; et al. Diastereoselective Synthesis of (±)-Ambrox by Titanium(III)-Catalyzed Radical Tandem Cyclization. Synlett 2016, 27, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Pozo Morales, L.; Díaz Ojeda, E. Cp2TiCl-catalyzed, concise synthetic approach to marine natural product (±)-cyclozonarone. Synth. Commun. 2019, 49, 2554–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Enríquez, L.; Jaraíz, M.; Pozo Morales, L.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Díaz Ojeda, E. A Concise Route for the Synthesis of Tetracyclic Meroterpenoids: (±)-Aureol Preparation and Mechanistic Interpretation. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-García, I.; López-Martínez, J.L.; López-Domene, R.; Muñoz-Dorado, M.; Rodríguez-García, I.; Álvarez-Corral, M. Enantioselective total synthesis of putative dihydrorosefuran, a monoterpene with an unique 2,5-dihydrofuran structure. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2022, 18, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-García, I. Marine Puupehenone and Puupehedione: Synthesis and Future Perspectives. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martínez, J.L.; Torres-García, I.; Moreno-Gutiérrez, I.; Oña-Burgos, P.; Rosales Martínez, A.; Muñoz-Dorado, M.; Álvarez-Corral, M.; Rodríguez-García, I. A Concise Diastereoselective Total Synthesis of α-Ambrinol. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-Maecker, R.N.; Rodríguez-García, I. Unifying the Synthesis of a Whole Family of Marine Meroterpenoids through a Biosynthetically Inspired Sequence of 1,2-Hydride and Methyl Shifts as Key Step. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjona, O.; Garranzo, M.; Mahugo, J.; Maroto, E.; Plumet, J.; Sáez, B. Total synthesis of both enantiomers of 15-oxopuupehenol methylendioxy derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7249–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordine, G.; Bick, S.; Möller, U.; Welzel, P.; Daucher, B.; Maas, G. Studies on forskolin ring C forming reactions. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rosales Martínez, A.; Rodríguez-García, I. Synthesis of Marine (−)-Pelorol and Future Perspectives. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/md22090425

Rosales Martínez A, Rodríguez-García I. Synthesis of Marine (−)-Pelorol and Future Perspectives. Marine Drugs. 2024; 22(9):425. https://doi.org/10.3390/md22090425

Chicago/Turabian StyleRosales Martínez, Antonio, and Ignacio Rodríguez-García. 2024. "Synthesis of Marine (−)-Pelorol and Future Perspectives" Marine Drugs 22, no. 9: 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/md22090425

APA StyleRosales Martínez, A., & Rodríguez-García, I. (2024). Synthesis of Marine (−)-Pelorol and Future Perspectives. Marine Drugs, 22(9), 425. https://doi.org/10.3390/md22090425