Production of Carotenoids and Phospholipids by Thraustochytrium sp. in Batch and Repeated-Batch Culture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

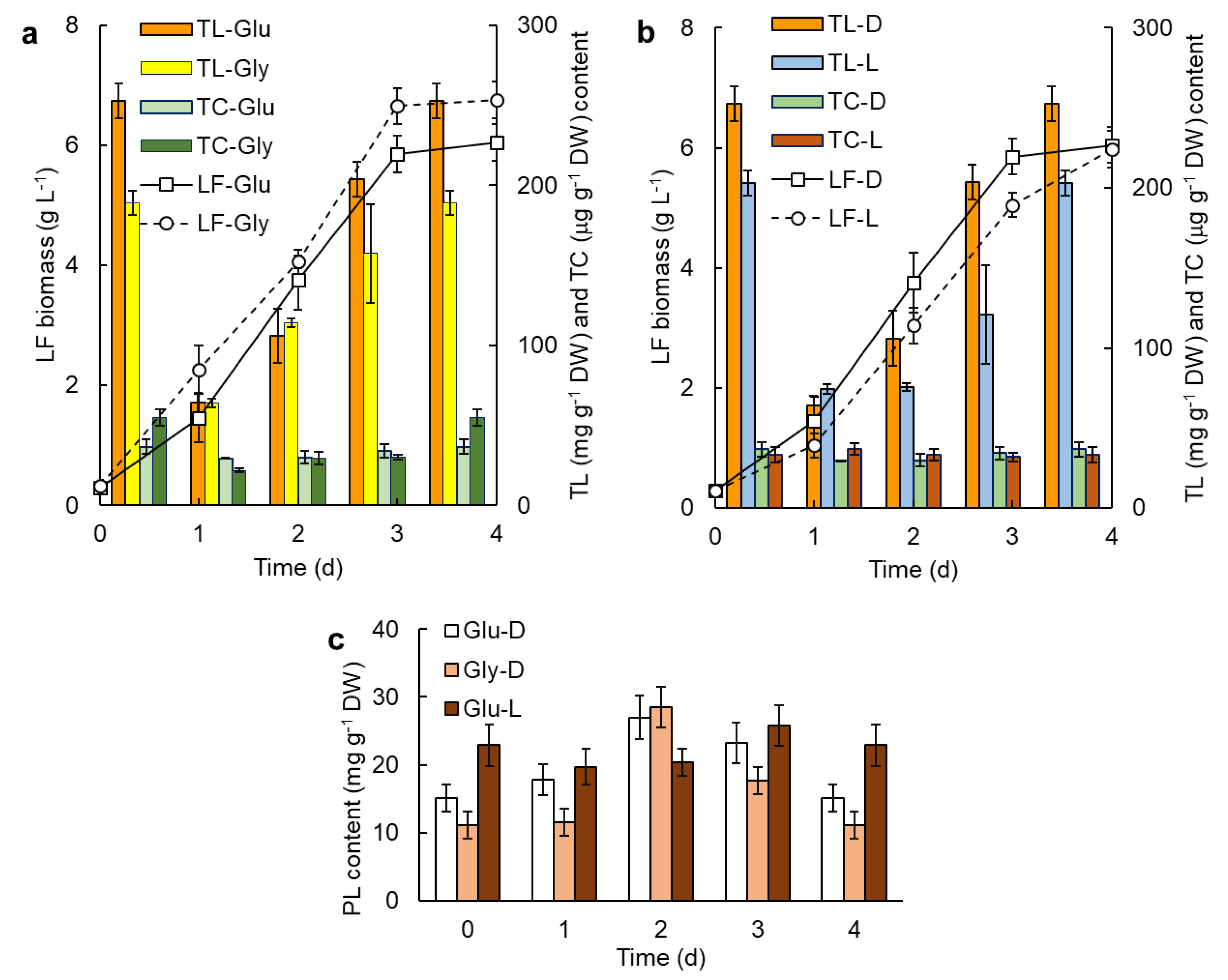

2.1. Batch Culture

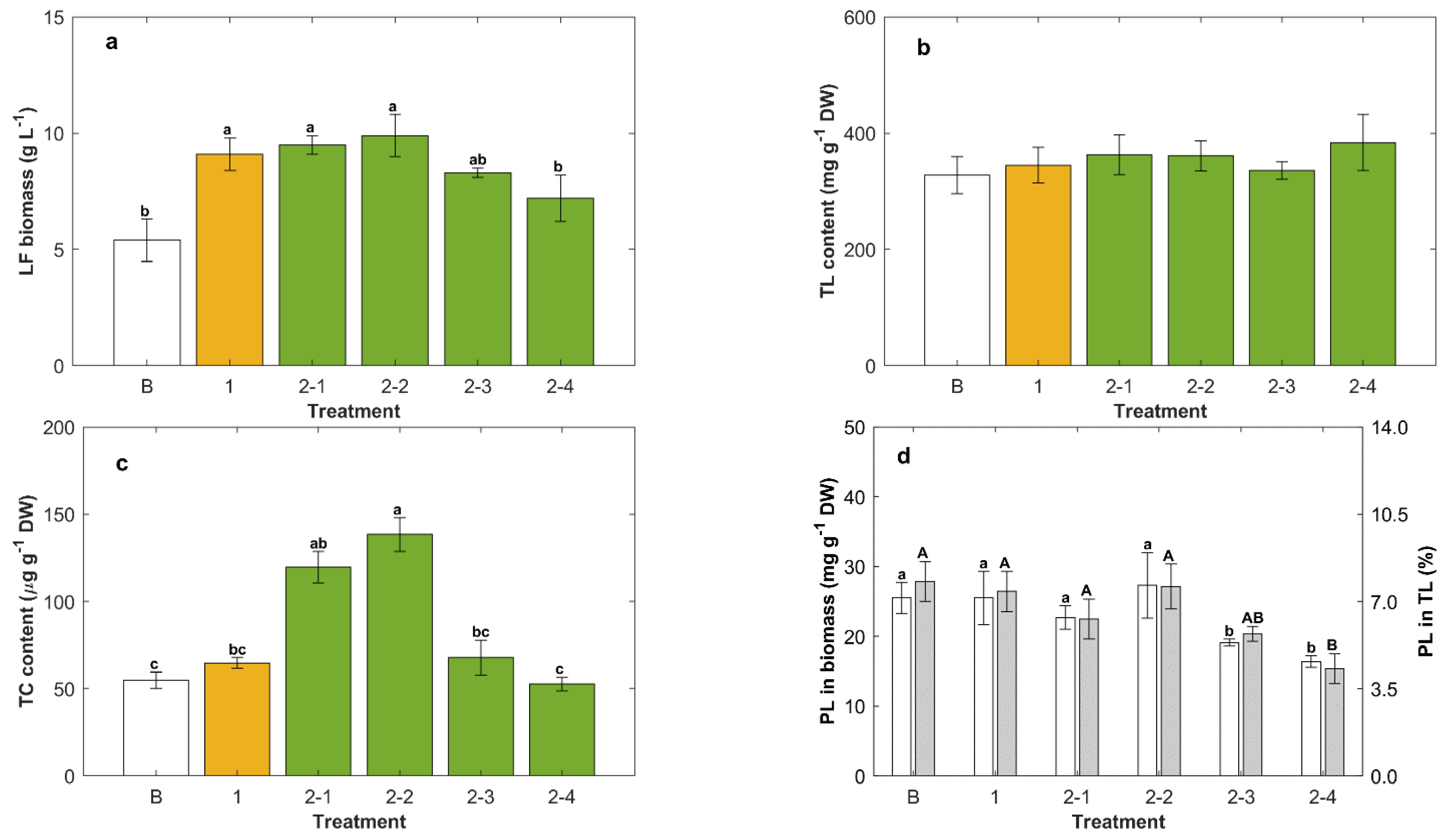

2.2. Repeated-Batch Cultures Fed Once

2.3. Effect of the Carbon Source in Repeated-Batch Cultures Fed Twice

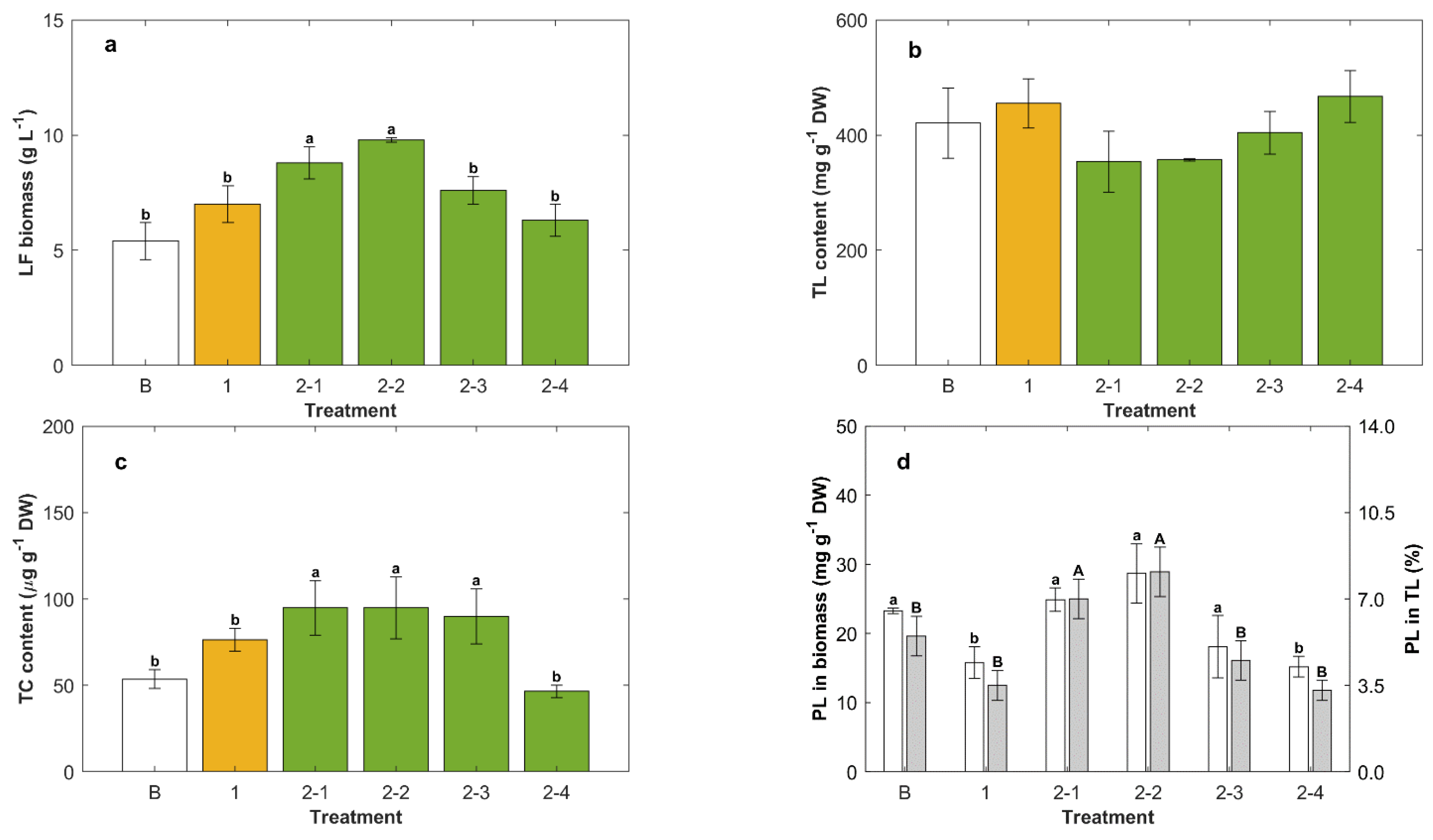

2.4. Effect of Temperature in Repeated-Batch Cultures

2.5. Effect of Cold Storage after Lipid Synthesis in Repeated-Batch Cultures Fed Twice

2.6. Fatty Acid Composition of Total Lipids in RT2316-16

- The odd-carbon fatty acids (C15:0 and C17:0) occurred (≥1.2% of TL) in the biomass grown in CM3 but not in the biomass grown on glucose.

- The monounsaturated fatty acid (C16:1, C18:1, C24:1) content in total lipids of the CM3-fed biomass grown at 15 °C was 80% greater than in the total lipids of the biomass grown at 5 °C. However, if the feed comprised only glucose, the three noted monounsaturated fatty acids in total lipids were only 20% more at 5 °C compared to 15 °C.

- Irrespective of the feed, γ-linoleic acid (C18:3cis6,9,12) was found only in the biomass grown at 5 °C and not in the biomass grown at 15 °C. In contrast with this, irrespective of the feed, tetracosanoic acid (C24:0) was found only in total lipids of the biomass grown at 15 °C.

- EPA and DHA occurred in all lipids, irrespective of the composition of the feed and the incubation temperature. In all cases, substantially more DHA existed in total lipids than EPA.

3. Discussion

3.1. Effect of Light on the Production of Lipid Compounds

3.2. Effect of the Carbon Source on the Production of Lipids

3.3. Yeast Extract Enhanced the Phospholipids Content of the Biomass

3.4. Carotenoids Synthesis Is Growth Rate Related in RT2316-16

3.5. Fatty Acids Produced by RT2316-16 under Different Conditions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Culture Experiments

4.1.1. Inoculum Preparation

4.1.2. Effect of the Carbon Source and Light on the Production of Biomass and Lipids

4.1.3. Repeated-Batch Cultures

4.2. Analysis

4.2.1. Concentrations of Biomass and Residual Sugars

4.2.2. Extraction of Total Lipids and Determination of Fatty Acid Profile

4.2.3. Quantification of Phospholipids

4.2.4. Extraction and Quantification of Carotenoids

4.2.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chi, G.; Xu, Y.; Cao, X.; Li, Z.; Cao, M.; Chisti, Y.; He, H. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by Schizochytrium (Aurantiochytrium) spp. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 55, 107897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, E.; Hayashi, Y.; Hama, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Inagaki, M.; Ito, M. A novel phosphatidylcholine which contains pentadecanoic acid at sn-1 and docosahexaenoic acid at sn-2 in Schizochytrium sp. F26-b. J. Biochem. 2006, 140, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, E.; Ikeda, K.; Nutahara, E.; Hayashi, M.; Yamashita, A.; Taguchi, R.; Doi, K.; Honda, D.; Okino, N.; Ito, M. Novel lysophospholipid acyltransferase PLAT1 of Aurantiochytrium limacinum F26-b responsible for generation of palmitate-docosahexaenoate-phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylethanolamine. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Morita, E.; Kumon, Y.; Nakahara, T.; Kagiwada, S.; Noguchi, T. Docosahexaenoic acid production and lipid-body formation in Schizochytrium limacinum SR21. Mar. Biotechnol. 2006, 8, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.H.; Chen, W.C.; Wang, Z.M.; Liu, P.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Lin, C.B.; Lu, S.H.; Huang, F.H.; Wan, X. Lipid Distribution pattern and transcriptomic insights revealed the potential mechanism of docosahexaenoic acid traffics in Schizochytrium sp. A-2. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 9683–9693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodchoey, K.; Verduyn, C. Growth, fatty acid profile in major lipid classes and lipid fluidity of Aurantiochytrium mangrovei SK-02 As a function of growth temperature. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, H.; Orikasa, Y.; Nishida, T. In vivo conversion of triacylglycerol to docosahexaenoic acid-containing phospholipids in a thraustochytrid-like microorganism, strain 12B. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1977–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, G.; Luo, Z.; Gu, S.; Wu, Q.; Chang, M.; Wang, X. Fatty acid shifts and metabolic activity changes of Schizochytrium sp. S31 cultured on glycerol. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 142, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.J.; Sun, G.N.; Ji, X.J.; Hu, X.C.; Huang, H. Compositional shift in lipid fractions during lipid accumulation and turnover in Schizochytrium sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagarde, M.; Bernoud, N.; Brossard, N.; Lemaitre-Delaunay, D.; Thies, F.; Croset, M.; Lecerf, J. Lysophosphatidylcholine as a preferred carrier form of docosahexaenoic acid to the brain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2001, 16, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picq, M.; Chen, P.; Perez, M.; Michaud, M.; Vericel, E.; Guichardant, M.; Lagarde, M. DHA metabolism: Targeting the brain and lipoxygenation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2010, 42, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aki, T.; Hachida, K.; Yoshinaga, M.; Katai, Y.; Yamasaki, T.; Kawamoto, S.; Kakizono, T.; Maoka, T.; Shigeta, S.; Suzuki, O.; et al. Thraustochytrid as a potential source of carotenoids. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2003, 80, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, G. Structure and properties of carotenoids in relation to function. FASEB J. 1995, 9, 1551–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galasso, C.; Corinaldesi, C.; Sansone, C. Carotenoids from marine organisms: Biological functions and industrial applications. Antioxidants 2017, 23, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyton, A.; Flores, L.; Shene, C.; Chisti, Y.; Larama, G.; Asenjo, J.A.; Armenta, R.E. Antarctic thraustochytrids as sources of carotenoids and high-value fatty acids. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L. Structure and function of biotin-dependent carboxylases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 863–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Sun, X.; Ji, X.; Chen, S.; Guo, D.; Huang, H. Enhancement of docosahexaenoic acid synthesis by manipulation of antioxidant capacity and prevention of oxidative damage in Schizochytrium sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 223, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Sen, B.; Bai, M.; He, Y.; Wang, G. Exogenous antioxidants improve the accumulation of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in Schizochytrium sp. PKU#Mn4. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Barrow, C.J.; Puri, M. Multiproduct biorefinery from marine thraustochytrids towards a circular bioeconomy. Trends Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöpf, L.; Mautz, J.; Sandmann, G. Multiple ketolases involved in light regulation of canthaxanthin biosynthesis in Nostoc punctiforme PCC 73102. Planta 2013, 237, 1279–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kwak, M.; Seo, J.; Ju, J.; Heo, S.; Park, S.; Hong, W. Enhanced production of carotenoids using a Thraustochytrid microalgal strain containing high levels of docosahexaenoic acid-rich oil. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 41, 1355–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orr, A.L.; Quinlan, C.L.; Perevoshchikova, I.V.; Brand, M.D. A refined analysis of superoxide production by mitochondrial sn-glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 42921–42935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mráček, T.; Drahota, Z.; Houštěk, J. The function and the role of the mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in mammalian tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1827, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, L.W. The evolution of per-cell organelle number. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 4, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranov, A.I.; Cook, M.; Ricicova, M.; Ben-Ari, G.; Gonzalez, C.; Hansen, C.; Tyers, M.; Amon, A. The rate of cell growth is governed by cell cycle stage. Genes Dev. 2009, 23, 1408–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, W.; Zhong, L.; Ta, M.T.; Shui, G.; Wenk, M.R.; Yang, H. The size and phospholipid composition of lipid droplets can influence their proteome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011, 415, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauchi-Sato, K.; Ozeki, S.; Houjou, T.; Taguchi, R.; Fujimoto, T. The surface of lipid droplets is a phospholipid monolayer with a unique fatty acid composition. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 44507–44512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruszecki, W.I.; Strzałka, K. Carotenoids as modulators of lipid membrane physical properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2005, 1740, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, B.; Han, D.; Sommerfeld, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, F.; Hu, Q. Molecular mechanisms of the coordination between astaxanthin and fatty acid biosynthesis in Haematococcus pluvialis (Chlorophyceae). Plant J. 2015, 81, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shene, C.; Leyton, A.; Rubilar, M.; Pinelo, M.; Acevedo, F.; Morales, E. Production of lipids and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) by a native Thraustochytrium strain. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2013, 115, 890–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, P.; Larama, G.; Flores, L.; Leyton, A.; Ili, C.G.; Asenjo, J.A.; Chisti, Y.; Shene, C. Temperature differentially affects gene expression in Antarctic thraustochytrid Oblongichytrium sp. RT2316-13. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bligh, E.; Dyer, W. A rapid method for total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOCS. Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 4th ed.; Fire-stone, D., Ed.; AOCS Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Vijayalakshmi, G.; Shobha, B.; Vanajakshi, V.; Divakar, S.; Manohar, B. Response surface methodology for optimization of growth parameters for the production of carotenoids by a mutant strain of Rhodotorula gracilis. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2001, 213, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathish, T.; Udayakiran, D.; Himabindu, K.; Lakshmi, P.; Sridevi, D.; Devarapalli, K.; Bhojaraju, P. HPLC Method for the determination of lycopene in crude oleoresin extracts. Asian J. 2009, 21, 139–148. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand-Harb, C.; Nicolas, M.G.; Dalgalarraondo, M.; Chobert, J.M. Determination of alkylation degree by three colori-metric methods and amino-acid analysis: A comparative study. Sci. Aliment. 1993, 13, 577–584. [Google Scholar]

| Culture Conditions | Total Carotenoids (μg g−1) | Canthaxanthin (%) | Astaxanthin (%) | β-Carotene (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batch * (glucose in the dark) | 37 ± 4 | 86.4 ± 0.4 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 8.7 ± 2.0 b |

| Batch * (glucose with light) | 33 ± 5 | 76.5 ± 4.2 a | 5.8 ± 1.0 | 17.7 ± 3.1 a |

| Batch * (glycerol in the dark) | 55 ± 5 a | 87.4 ± 0.7 | 7.1 ± 0.4 | 5.5 ± 0.3 c |

| Repeated-batch ⁑ (fed with CM) | 152 ± 9 b | 57.9 ± 3.7 a | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 40.8 ± 1.8 b |

| Repeated-batch ⁑ (fed with YE) | 168 ± 7 a | 61.4 ± 0.2 a | 5.1 ± 1.0 a | 33.4 ± 1.1 c |

| Repeated-batch ⁑ (fed with glucose) | 43 ± 3 c | 5.7 ± 2.0 b | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 95.6 ± 2.7 a |

| Fatty Acid | Glycerol, Dark | Glucose, DARK | Glucose, Light | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | |

| C14:0 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.3 |

| C16:0 | 22.5 ± 0.1 | 21.4 ± 0.7 | 21.8 ± 0.5 | 31.2 ± 6.6 | 28.8 ± 1.0 | 26.9 ± 0.7 | 30.1 ± 0.4 | 26.6 ± 2.5 | 28.0 ± 1.1 |

| C16:1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.6 ± 0.0 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

| C18:0 | 15.1 ± 0.2 | 23.2 ± 1.5 | 21.3 ± 1.4 | 12.9 ± 2.8 | 21.8 ± 0.6 | 13.3 ± 0.2 | 9.4 ± 1.2 | 18.0 ± 2.8 | 16.9 ± 4.3 |

| C18:1cis | 33.0 ± 1.9 | 35.5 ± 1.8 | 41.4 ± 0.4 | 23.4 ± 5.2 | 29.9 ± 2.9 | 41.0 ± 1.2 | 17.9 ± 1.0 | 29.4 ± 0.5 | 36.5 ± 1.0 |

| C18:2cis | 5.1 ± 0.1 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 5.9 ± 1.4 | 8.8 ± 0.6 |

| C22:1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| C20:5n-3 (EPA) | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 13.0 ± 3.9 | 4.8 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| C24:1 | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| C22:6n-3 (DHA) | 12.6 ± 1.0 | 5.6 ± 1.1 | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 19.6 ± 3.3 | 3.8 ± 2.2 | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 29.6 ± 1.3 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 1.3 |

| Others | 5.1 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 0.6 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 6.1 |

| Fatty Acid | CM3 | Glucose | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 °C | 15 °C | 5 °C | 15 °C | |

| C14:0 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 12.5 ± 7.4 | 5.1 ± 0.9 |

| C15:0 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| C16:0 | 29.3 ± 1.0 | 17.0 ± 0.6 | 21.0 ± 1.6 | 23.4 ± 7.6 |

| C16:1 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 13.9 ± 1.6 | 9.0 ± 5.2 |

| C17:0 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| C18:0 | 28.3 ± 0.3 | 25.4 ± 0.7 | 12.6 ± 1.1 | 23.0 ± 8.2 |

| C18:1cis | 18.7 ± 1.1 | 34.2 ± 0.6 | 19.9 ± 3.3 | 29.4 ± 3.9 |

| C18:2cis | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 1.9 |

| C18:3cis6,9,12 | 1.2 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 4.5 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| C24:0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| C20:5n-3 (EPA) | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 1.0 |

| C24:1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 1.6 |

| C22:6n-3 (DHA) | 2.3 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 1.0 | 6.6 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 1.7 |

| Others | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leyton, A.; Shene, C.; Chisti, Y.; Asenjo, J.A. Production of Carotenoids and Phospholipids by Thraustochytrium sp. in Batch and Repeated-Batch Culture. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20070416

Leyton A, Shene C, Chisti Y, Asenjo JA. Production of Carotenoids and Phospholipids by Thraustochytrium sp. in Batch and Repeated-Batch Culture. Marine Drugs. 2022; 20(7):416. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20070416

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeyton, Allison, Carolina Shene, Yusuf Chisti, and Juan A. Asenjo. 2022. "Production of Carotenoids and Phospholipids by Thraustochytrium sp. in Batch and Repeated-Batch Culture" Marine Drugs 20, no. 7: 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20070416

APA StyleLeyton, A., Shene, C., Chisti, Y., & Asenjo, J. A. (2022). Production of Carotenoids and Phospholipids by Thraustochytrium sp. in Batch and Repeated-Batch Culture. Marine Drugs, 20(7), 416. https://doi.org/10.3390/md20070416