Current Research on the Bioprospection of Linear Diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata: From Extraction Methodologies to Possible Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Bifurcaria bifurcata General Characteristics and Linear Diterpenes Chemical Families

- Empire: Eukaryota

- Kingdom: Chromista

- Phylum: Ochrophyta

- Class: Phaeophyceae

- Subclass: Fucophycidae

- Order: Fucales

- Family: Sargassaceae

- Genus: Bifurcaria

Linear Diterpenes Families of B. bifurcata

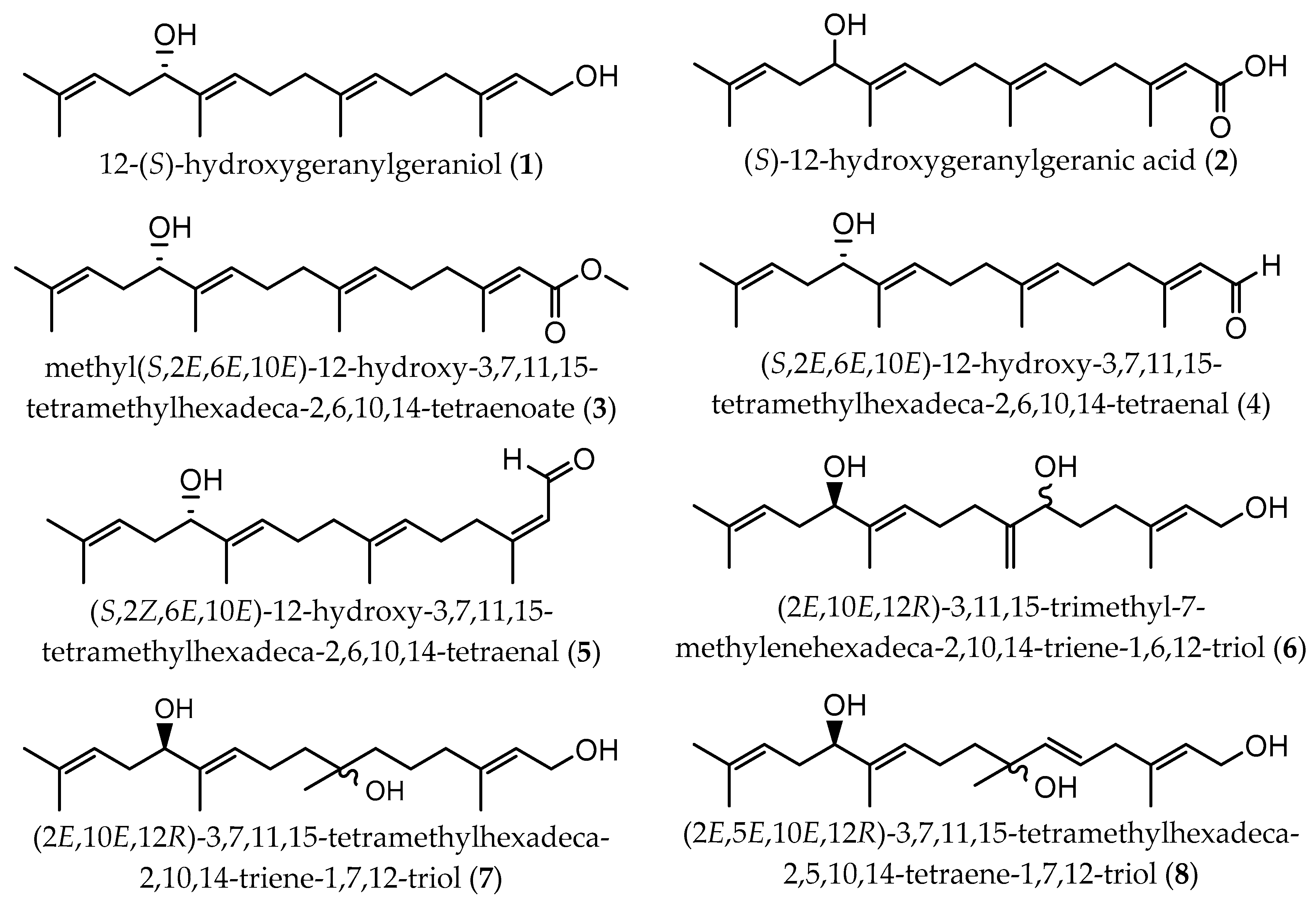

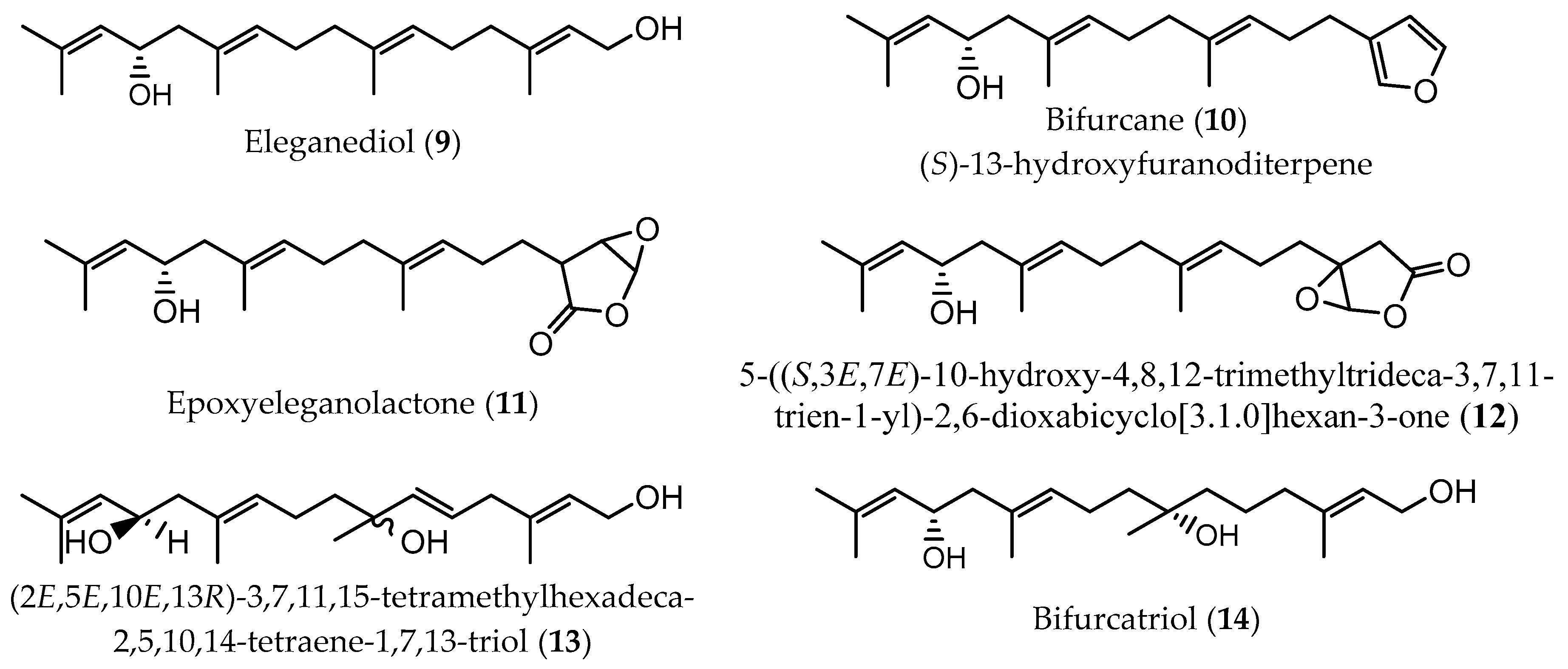

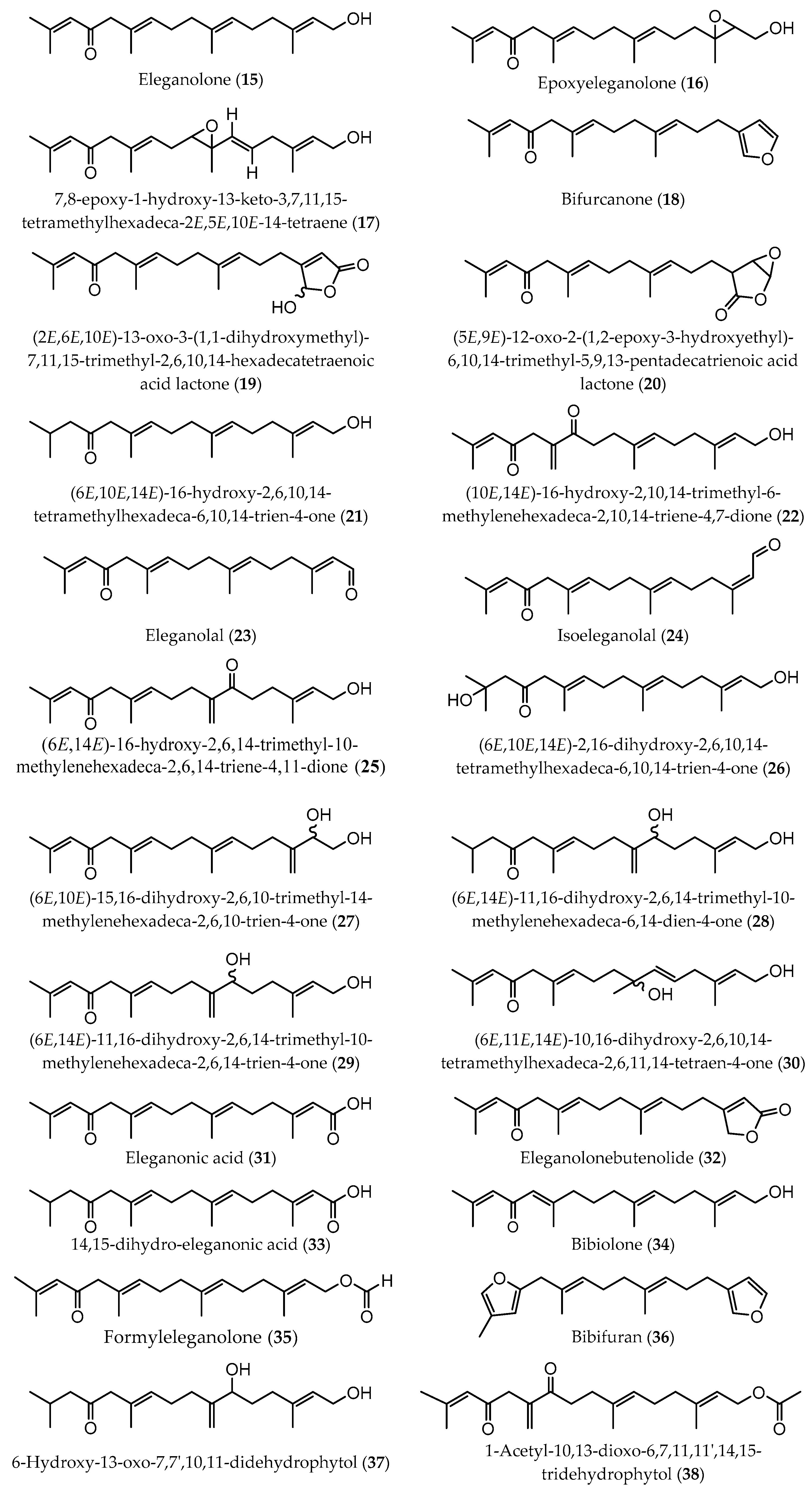

3. Characterization of Linear Diterpenes from B. bifurcata

3.1. Extraction and Fractionation Methodologies

3.2. Instrumental Analysis: Identification and Quantification

4. Biological Activities of B. bifurcata Diterpenes-Enriched Extracts: In vitro and In Chemico Assays

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity

4.2. Antifouling Activity

4.3. Antiproliferative Activity

4.4. Antioxidant Activity

4.5. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

4.6. Other Biological Activities

4.7. In Vitro Estimation of Toxicity

5. Potential Applications for B. bifurcata Extracts

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balina, K.; Romagnoli, F.; Blumberga, D. Seaweed biorefinery concept for sustainable use of marine resources. Energy Procedia 2017, 128, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernand, F.; Israel, A.; Skjermo, J.; Wichard, T.; Timmermans, K.R.; Golberg, A. Offshore macroalgae biomass for bioenergy production: Environmental aspects, technological achievements and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. COM(2012) 494—Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Blue Growth Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxemburg, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Stengel, D.B.; Connan, S. Natural Products From Marine Algae; Methods in Molecular Biology; Stengel, D.B., Connan, S., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1308, ISBN 978-1-4939-2683-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe, W.A.J.P.; Jeon, Y.J. Biological activities and potential cosmeceutical applications of bioactive components from brown seaweeds: A review. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klnc, B.; Cirik, S.; Turan, G.; Tekogul, H.; Koru, E. Seaweeds for Food and Industrial Applications. In Food Industry; InTechOpen: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, A.C.; Rodrigues, D.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; Gomes, A.M.P.; Duarte, A.C. Marine biotechnology advances towards applications in new functional foods. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zubia, M.; Fabre, M.S.; Kerjean, V.; Lann, K.L.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V.; Fauchon, M.; Deslandes, E. Antioxidant and antitumoural activities of some Phaeophyta from Brittany coasts. Food Chem. 2009, 116, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdt, S.L.; Kraan, S. Bioactive compounds in seaweed: Functional food applications and legislation. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 543–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuzumi, J.; Takahashi, T.; Yamane, T.; Kitao, Y.; Inagake, M.; Ohya, K.; Nishino, H.; Tanaka, Y. Inhibitory effects of fucoxanthin, a natural carotenoid, on N-ethyl-N′-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine-induced mouse duodenal carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1993, 68, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyanagi, S.; Tanigawa, N.; Nakagawa, H.; Soeda, S.; Shimeno, H. Reviewed the Structured and Bioactive Compound of Fucoidan. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003, 65, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesekara, I.; Yoon, N.Y.; Kim, S.K. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava (Phaeophyceae): Biological activities and potential health benefits. BioFactors 2010, 36, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blunt, J.W.; Carroll, A.R.; Copp, B.R.; Davis, R.A.; Keyzers, R.A.; Prinsep, M.R. Marine natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2018, 35, 8–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, J.; Culioli, G.; Köck, M. Linear diterpenes from the marine brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata: A chemical perspective. Phytochem. Rev. 2013, 12, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Lann, K.; Jégou, C.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V. Effect of different conditioning treatments on total phenolic content and antioxidant activities in two Sargassacean species: Comparison of the frondose Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt and the cylindrical Bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross. Phycol. Res. 2008, 56, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. Bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org/search/genus/detail/?genus_id=78&-session=abv4:AC1F25E1169cb0028AQS8B54C575 (accessed on 3 May 2019).

- Le Lann, K.; Rumin, J.; Cérantola, S.; Culioli, G.; Stiger-Pouvreau, V. Spatiotemporal variations of diterpene production in the brown macroalga Bifurcaria bifurcata from the western coasts of Brittany (France). J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 26, 1207–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culioli, G.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Richou, M.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. Seasonal variations in the chemical composition of Bifurcaria bifurcata (Cystoseiraceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2002, 30, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biard, J.F.; Verbist, J.F.; Floch, R.; Letourneux, Y. Epoxyeleganolone et eleganediol, deux nouveaux diterpenes de Bifurcaria bifurcata ross (cystoseiracees). Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 1849–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biard, J.F.; Verbist, J.F.; Letoumeux, Y. Cétols Diterpeniques à Activite Antimicrobienne de Bifurcaria bifurcata. J. Med. Plant Res. 1980, 40, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallé, J.; Attitoua, B.; Kaiser, M.; Rusig, A.; Lobstein, A.; Vonthron-Sénécheau, C. Eleganolone, a Diterpene from the French Marine Alga Bifurcaria bifurcata Inhibits Growth of the Human Pathogens Trypanosoma brucei and Plasmodium falciparum. Mar. Drugs 2013, 11, 599–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardella, F.; Margueritte, L.; Lamure, B.; Martine, J.; Viéville, P.; Bourjot, M. Targeted discovery of bioactive natural products using a pharmacophoric deconvolution strategy: Proof of principle with eleganolone from Bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross. Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 26, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellio, C.; Thomas-Guyon, H.; Culioli, G.; Piovettt, L.; Bourgougnon, N.; le Gal, Y. Marine antifoulants from Bifurcaria bifurcata (Phaeophyceae, Cystoseiraceae) and other brown macroalgae. Biofouling 2001, 17, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortalo-Magné, A.; Culioli, G.; Valls, R.; Pucci, B.; Piovetti, L. Polar acyclic diterpenoids from Bifurcaria bifurcata (Fucales, Phaeophyta). Phytochemistry 2005, 66, 2316–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps, M.; Briand, J.F.; Guentas-Dombrowsky, L.; Culioli, G.; Bazire, A.; Blache, Y. Antifouling activity of commercial biocides vs. natural and natural-derived products assessed by marine bacteria adhesion bioassay. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 1032–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geraci, S.; Faimali, M.; Piovetti, L.; Cimino, G. Antifouling from Nature: Laboratory Test with Balanus amphitrite Darwin on Algae and Sponges. In 10th International Congress on Marine Corrosion and Fouling, University of Melbourne, February 1999; Lewis, J.A., Ed.; DSTO Aeronautical and Maritime Research Laboratory: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2001; pp. 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Combaut, G.; Piovetti, L. A novel acyclic diterpene from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1983, 22, 1787–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hougaard, L.; Anthoni, U.; Christophersen, C.; Nielsen, P.H. Eleganolone derived diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1991, 30, 3049–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, R.; Piovetti, L.; Banaigs, B.; Archavlis, A.; Pellegrini, M. (S)-13-hydroxygeranylgeraniol-derived furanoditerpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1995, 39, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göthel, Q.; Lichte, E.; Köck, M. Further eleganolone-derived diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 1873–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culioli, G.; Daoudi, M.; Mesguiche, V.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. Geranylgeraniol-derived diterpenoids from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1999, 52, 1447–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culioli, G.; Mesguiche, V.; Piovetti, L.; Valls, R. Geranylgeraniol and geranylgeraniol-derived diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata (Cystoseiraceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1999, 27, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culioli, G.; Di Guardia, S.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. Geranylgeraniol-derived diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria Bifurcata: Comparison with two other Cystoseiraceae species. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2000, 28, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göthel, Q.; Muñoz, J.; Köck, M. Formyleleganolone and bibifuran, two metabolites from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochem. Lett. 2012, 5, 693–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonthron-sé, C.; Kaiser, M.; Devambez, I.; Vastel, A.; Mussio, I.; Rusig, A. Antiprotozoal Activities of Organic Extracts from French Marine Seaweeds. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 922–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maréchal, J.P.; Culioli, G.; Hellio, C.; Thomas-Guyon, H.; Callow, M.E.; Clare, A.S.; Ortalo-Magné, A. Seasonal variation in antifouling activity of crude extracts of the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata (Cystoseiraceae) against cyprids of Balanus amphitrite and the marine bacteria Cobetia marina and Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis. J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 2004, 313, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D.; Thomas-Guyon, H.; Jacquot, C.; Jugé, M.; Culioli, G.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Piovetti, L.; Roussakis, C. An extract from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata induces irreversible arrest of cell proliferation in a non-small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma line. J. Appl. Phycol. 2006, 18, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.; Trindade, S.; Oliveira, C.; Parreira, P.; Rosa, D.; Duarte, M.; Ferreira, I.; Cruz, M.; Rego, A.; Abreu, M.; et al. Lipophilic fraction of cultivated Bifurcaria bifurcata R. Ross: Detailed composition and in vitro prospection of current challenging bioactive properties. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balboa, E.M.; Conde, E.; Moure, A.; Falqué, E.; Domínguez, H. In vitro antioxidant properties of crude extracts and compounds from brown algae. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 1764–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, X.; Zhou, X.-F.; Yang, X.-W.; Liu, Y. Handbook of Marine Macroalgae; Kim, S.-K., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011; ISBN 9781119977087. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, H.; König, G.M. Terpenoids from marine organisms: Unique structures and their pharmacological potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2006, 5, 115–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, M.K.; Koul, A.; Kaul, S. Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase: A key enzyme in isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway and potential molecular target for drug development. N. Biotechnol. 2013, 30, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valls, R.; Banaigs, B.; Piovetti, L.; Archavlis, A.; Artaud, J. Linear diterpene with antimitotic activity from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 1585–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culioli, G.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Daoudi, M.; Thomas-Guyon, H.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. Trihydroxylated linear diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valls, R.; Banaigs, B.; Francisco, C.; Codomier, L.; Cave, A. An Acyclic Diterpene from the Brown Alga Bifurcaria bifurcata; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1986; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Culioli, G.; Daoudi, M.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. (S)-12-Hydroxygeranylgeraniol-derived diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmak, L.; Zerzouf, A.; Valls, R.; Banaigs, B.; Jeanty, G.; Francisco, C. Acyclic diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2347–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrniotopoulos, V.; Firsova, D.; Rae, M.; Heesch, S.; Fearnhead, H.; Tasdemir, D. Linear diterpenes with anticancer activity from the irish brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Planta Med. 2014, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hattab, M.; Ben Mesaoud, M.; Daoudi, M.; Ortalo-Magné, A.; Culioli, G.; Valls, R.; Piovetti, L. Trihydroxylated linear diterpenes from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2008, 36, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyrniotopoulos, V.; Merten, C.; Kaiser, M.; Tasdemir, D. Bifurcatriol, a new antiprotozoal acyclic diterpene from the brown alga Bifurcaria bifurcata. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Alves, C.; Freitas, R.; Martins, A.; Pinteus, S.; Ribeiro, J.; Gaspar, H.; Alfonso, A.; Pedrosa, R. Antioxidant and Neuroprotective Potential of the Brown Seaweed Bifurcaria bifurcata in an in vitro Parkinson’s Disease Model. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainane, T.; Abourriche, A.; Bennamara, A.; Charrouf, M.; Lemrani, M. Antileishmanial activity of extracts from a brown seaweed Bifurcaria bifurcata the atlantic coast of Casablanca (Morocco). BioTechnology 2015, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Della Pieta, F.; Bilia, A.R.; Breschi, M.C.; Cinelli, F.; Morelli, I.; Scatizzi, R. Crude extracts and two linear diterpenes from Cystoseira balearica and their activity. Planta Med. 1993, 59, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pinteus, S.; Silva, J.; Alves, C.; Horta, A.; Fino, N.; Rodrigues, A.I.; Mendes, S.; Pedrosa, R. Cytoprotective effect of seaweeds with high antioxidant activity from the Peniche coast (Portugal). Food Chem. 2017, 218, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, C.; Pinteus, S.; Simões, T.; Horta, A.; Silva, J.; Tecelão, C.; Pedrosa, R. Bifurcaria bifurcata: A key macro-alga as a source of bioactive compounds and functional ingredients. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1638–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, X. High-Pressure processing as emergent technology for the extraction of bioactive ingredients from plant materials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 837–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, E.M.C.; Castro, L.M.G.; Moreira, S.A.; Pintado, M.; Saraiva, J.A. Comparison of emerging technologies to extract high-added value compounds from fruit residues: Pressure- and electro-based technologies. Food Eng. Rev. 2017, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibtissam, C.; Hassane, R.; José, M.; Francisco, D.S.J.; Antonio, G.V.J.; Hassan, B.; Mohamed, K. Screening of antibacterial activity in marine green and brown macroalgae from the coast of Morocco. African J. Biotechnol. 2009, 8, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Agregán, R.; Munekata, P.E.; Domínguez, R.; Carballo, J.; Franco, D.; Lorenzo, J.M. Proximate composition, phenolic content and in vitro antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts of the seaweeds Ascophyllum nodosum, Bifurcaria bifurcata and Fucus vesiculosus. Effect of addition of the extracts on the oxidative stabi. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azmir, J.; Zaidul, I.S.M.; Rahman, M.M.; Sharif, K.M.; Mohamed, A.; Sahena, F.; Jahurul, M.H.A.; Ghafoor, K.; Norulaini, N.A.N.; Omar, A.K.M. Techniques for extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials: A review. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spavieri, J.; Allmendinger, A.; Kaiser, M.; Casey, R.; Hingley-wilson, S.; Lalvani, A.; Guiry, M.D.; Blunden, G.; Tasdemir, D. Antimycobacterial, Antiprotozoal and Cytotoxic Potential of Twenty-one Brown Algae (Phaeophyceae) from British and Irish Waters. Phyther. Res. 2010, 24, 1724–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.W.; Hsu, C.P.; Yang, B.B.; Wang, C.Y. Advances in the extraction of natural ingredients by high pressure extraction technology. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, F.J.; Zhu, Z.; Koubaa, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S.; Orlien, V. Green alternative methods for the extraction of antioxidant bioactive compounds from winery wastes and by-products: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 49, 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Pieta, F.; Breschi, M.C.; Scatizzi, R.; Cinelli, F. Relaxing activity of two linear diterpenes from Cystoseira brachycarpa var. balearica on the contractions of intestinal preparations. Planta Med. 1995, 61, 493–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador, Â.; Król, E.; Lemos, V.; Santos, S.; Bento, F.; Costa, C.; Almeida, A.; Szczepankiewicz, D.; Kulczyński, B.; Krejpcio, Z.; et al. Effect of Elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) Extract Supplementation in STZ-Induced Diabetic Rats Fed with a High-Fat Diet. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devillers, J.; Pandard, P.; Thybaud, E.; Merle, A. Interspecies correlations for predicting the acute toxicity of xenobiotics. In Ecotoxicology Modeling; Emerging Topics in Ecotoxicology; Devillers, J., Ed.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 85–115. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, J.M.; Trigo, M.; Barros-Velázquez, J.; Aubourg, S.P. Quality Enhancement of Chilled Lean Fish by Previous Active Dipping in Bifurcaria bifurcata Alga Extract. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2018, 11, 1662–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abboud, Y.; Saffaj, T.; Chagraoui, A.; El Bouari, A.; Brouzi, K.; Tanane, O.; Ihssane, B. Biosynthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of copper oxide nanoparticles ( CONPs ) produced using brown alga extract (Bifurcaria bifurcata). Appl. Nanosci. 2014, 4, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

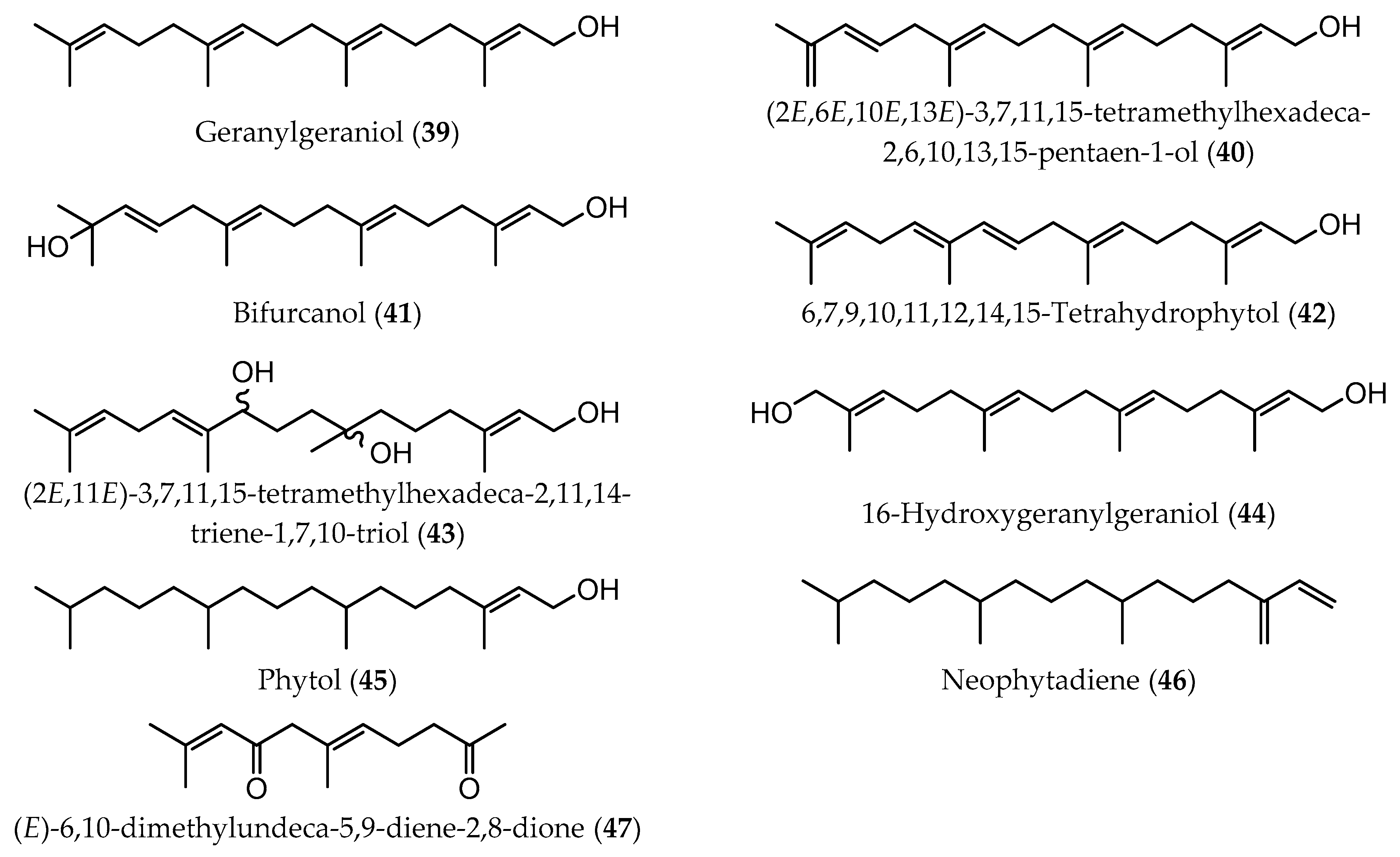

| Extraction Methodology | EY a | Sample Pretreatment | Fractionation/Purification | Identification/Analysis | Compound (Content b) | Time of Collection/Geographical. Origin | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EtOAc S–L extraction | 1.70 | Freeze-dried | Chromatography (on Silica gel) eluted with EtOAc-n-heptane (4:1) and monitored at 270 nm; Bio-guided fractionation: chromatography (on a Lobar RP-8 column) with EtOH-H2O; Fr. purification with MeCN-H2O or EtOAc-CHCl3. | (1H and 13C) NMR, MS | 9 (0.06) | July to August/Roscoff, Brittany, France | [28] |

| 15 (0.07) | |||||||

| 18 (0.11) | |||||||

| 19 (0.03) | |||||||

| 20 (0.02) | |||||||

| EtOAc S–L extraction | N.D. | Freeze-dried | LC using Silica gel with a solvent gradient from DCM to DCM-MeOH (80:20); CC (on Silica gel) with solvent gradient DCM-MeOH (100:0 to 97:3) HPLC (RP18 column) with a gradient elution (from H2O-MeCN (60:40), H2O-MeCN (80:20) to MeOH) | HRESIMS, 1D and 2D NMR | 10 | September/Roscoff, Brittany, France | [30] |

| 15 | |||||||

| 18 | |||||||

| 21 | |||||||

| 27 | |||||||

| 31 | |||||||

| 32 | |||||||

| 33 | |||||||

| 34 | |||||||

| 41 | |||||||

| EtOAc S–L extraction, at RT | 4.80 | Freeze-dried and ground | Successive flash and CC (on Silica gel), eluting with cyclohexane—EtOAc mixture; Bio-guided fractionation: CC (on Silica gel), with cyclohexane-EtOAc | HREIMS, (1H and 13C) NMR | 15 (0.004) | November to September/Basse-Normandie, France | [21] |

| EtOAc S–L extraction, at RT | N.D. | Freeze-dried and ground | Flash chromatography eluting with a H2O-MeOH mixture of increasing polarity (95:5–0:100 in 30 minutes) | 2D NMR, HPLC-DAD-MS-SPE-NMR | 15 | June/Cap Lévi, English Channel, France | [22] |

| EtOAc S–L extraction, at RT | 4.8 | Freeze-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from DCM to DCM-MeOH (80:20) UV-ESI-DAD-HPLC (using a Kromasil RP18 column) eluted with a solvent gradient H2O-MeCN-MeOH | (1H and 13C) NMR, HRESI(+)MS | 35 (0.002) | September/Roscoff, Brittany, France | [34] |

| 36 (0.001) | |||||||

| 44 (0.0004) | |||||||

| CHCl3 S–L extraction | N.D. | Normal and reverse phase flash CC and RP18 HPLC | 1D and 2D NMR, HRMS | 9 | May/Kilkee, County Clare of Ireland | [48] | |

| 10 | |||||||

| CHCl3-EtOH S–L extraction | 1.52 | Freeze-dried and ground | Partitioning between H2O and Et2O; Et2O-soluble material: CC (on Silica gel) eluted with hexane-EtOAc (2:3); HPLC (EtOAc–isooctane, 2:3), with RI monitoring | IR, (1H and 13C) NMR, EIMS | 1 (0.86) | -/Atlantic coast Morocco | [45] |

| CHCl3-MeOH S–L extraction, at RT | 5.53 | Shade-dried and ground | Partitioning in the mixture MeOH-isooctane (1:1); MeOH phase: dissolved in the mixture MeOH-CHCl3-H2O (4:3:1); Organic phase: CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from isooctane to EtOAc and then from EtOAc to MeOH. | HREIMS, (1H and 13C) NMR | 1 (0.37) | December/Oualidia, Morocco | [44] |

| 6 (0.01) | |||||||

| 7 (0.004) | |||||||

| CHCl3- MeOH S–L extraction; Et2O S–L extraction of aqueous phase | 1.95 g ext | Freshly collected | Open CC (on Silica gel) eluted with hexane to EtOAc (2:3); HPLC (eluent EtOAc-isooctane, 2:3). | IR, UV, (1H and 13C) NMR, EIMS, HRMS | 2 (0.17) | -/Morocco | [47] |

| 40 (0.02) | |||||||

| CHCl3-MeOH S–L extraction | 2.63 | Shade-dried | Partitioning in the mixture MeOH-isooctane (1:1); MeOH extract: dissolution in the mixture MeOH-CHCl3-H2O (4:3:1); Organic extract: fractionation on silica gel column eluted with EtOAc and EtOAc-MeOH (98:2 and 95:5); HPLC on C-18 reversed-phase column, eluting with MeCN-H2O (1:1 and/or 2:3). | HRMS, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR | 8 | -/Oualidia, Morocco | [49] |

| 43 | |||||||

| CHCl3-MeOH S–L extraction, at RT CHCl3-H2O L–L extraction | 6.92 | Air-dried and ground | MeOH extract: defatting with n-hexane; CC (on Silica gel) using mixtures of CHCl3-MeOH (from CHCl3 to CHCl3-MeOH, 1:1). | HPLC | 9 | July/Quiberon, Brittany, France | [37] |

| 13 | |||||||

| 15 | |||||||

| 21 | |||||||

| 25 | |||||||

| 26 | |||||||

| 27 | |||||||

| 28 | |||||||

| 29 | |||||||

| 30 | |||||||

| 39 | |||||||

| CHCl3- MeOH S–L extraction, at RT | 3.11 | Shade-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from cyclohexane to EtOAc and then from EtOAc to MeOH; HPLC on an analytical C-18 reverse-phase column (eluent, MeCN-H2O), with RI monitoring | HREIMS, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR | 9 (0.15) | July/Quiberon, Brittany, France | [24] |

| 13 (0.0001) | |||||||

| 15 (0.40) | |||||||

| 21 (0.01) | |||||||

| 25 (0.0001) | |||||||

| 26 (0.0003) | |||||||

| 27 (0.0002) | |||||||

| 28 (0.0001) | |||||||

| 29 (0.0005) | |||||||

| 30 (0.0005) | |||||||

| 39 (0.008) | |||||||

| 47 (0.01) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT | 1.65 | Freeze-dried and powder | Partitioning between H2O and Et2O; Et2O-soluble material: CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from hexane to EtOAc; HPLC (eluent, EtOAc–isooctane), with RI monitoring | HRMS, EIMS, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR | 1 (0.33–0.34) | January to December/Atlantic coast of Morocco | [43] |

| 2 (0.07–0.10) | |||||||

| 9 (0.10–0.12; 0.36–0.38) | |||||||

| 15 (0.29–0.32) | |||||||

| 40 (0.03) | |||||||

| 41 (0.01;0.04–0.05) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction | 2.94 | Air-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a gradient from isooctane to EtOAc; HPLC (eluent, isooctane-EtOAc); Semi-preparative and then analytical normal-phase HPLC with RI-monitoring. | 1D and 2D NMR | 1 (0.71) | November/Oualidia, Morocco | [23] |

| 39 (0.12) | |||||||

| 3.15 | 9 (0.14) | December/Quiberon, Brittany, France | |||||

| 15 (0.47) | |||||||

| 21 (0.01) | |||||||

| 22 (0.01) | |||||||

| 25 (0.02) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT | 2.94 | Shade-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from isooctane to EtOAc Semi-preparative normal phase HPLC (eluent, EtOAc-isooctane), with RI monitoring | HRMS, (1H and 13C) NMR | 1 (0.71) | December/Oualidia, Morocco | [46] |

| 2 (0.03) | |||||||

| 3 (0.08) | |||||||

| 4 (0.01) | |||||||

| 5 (0.004) | |||||||

| 39 (0.12) | |||||||

| 42 (0.01) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction | N.D. | Freeze-dried | Preparative HPLC (DCM-EtOAc, 90:10) | UV, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR, MS | 9 (0.28) | -/Loire-Atlantique, France | [19] |

| 16 (0.06) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction | N.D. | Shade-dried | Separation in different fractions | 9 | -/Brittany, France | [26] | |

| 15 | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT, for 48h | 2.2-2.9 | Air-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from isooctane to EtOAc; Normal-phase HPLC (eluent, isooctane-EtOAc, 2:3), with RI-monitoring | IR, UV, HRMS, 1D and 2D NMR | 9 (1.12) | July to June/Roscoff, Brittany, France | [36] |

| 10 (0.37) | |||||||

| 15 (0.06) | |||||||

| 39 (0.02) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT | 2.40 | Freeze-dried and ground | Partitioning between H2O and Et2O; Et2O-soluble material: CC (on Silica gel) eluted with hexane-EtOAc (1:1); HPLC (EtOAc–isooctane), with RI monitoring. | HRMS, EIMS, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR | 9 (0.15) | July to August/Roscoff, Brittany, France | [29] |

| 10 (0.23) | |||||||

| 11 (0.03) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT | 3.15 | Shade-dried and ground | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from isooctane to EtOAc; Semi-preparative normal-phase HPLC (eluent, EtOAc-isooctane), with RI monitoring | HRMS, EIMS, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR. | 9 (0.06) | December/Quiberon and Roscoff, Brittany, France | [31] |

| 15 (0.01) | |||||||

| 21 (0.01) | |||||||

| 22 (0.02) | |||||||

| 25 (0.03) | |||||||

| 2.40 | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from hexane to Et2O; HPLC (EtOAc- isooctane, 2:3), with RI monitoring. | 9 (0.04) | |||||

| 10 (0.06) | |||||||

| 11 (0.01) | |||||||

| 12 (0.007) | |||||||

| 15 (0.003) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction | N.D. | Dried | LC using Silica gel; HPLC of the most polar fraction; | IR, MS, NMR | 9 | -/Quiberon, Brittany, France | [33] |

| 25 | |||||||

| 47 | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction, at RT | N.D. | Crushed and freeze-dried | Insoluble impurities and pigments elimination with isooctane and EtOH-H2O, respectively; TLC (eluted with Et2O-petroleum ether, 50:50 or DCM-EtOAc 70:30); CC (on Silica gel, eluted with Et2O-petroleum ether, 75:25) Semi-preparative HPLC | UV, IR, (1H and 13C) NMR, MS | 15 (2) | -/Loire-Atlantique, France | [20] |

| Et2O S–L extraction (3x) (3h at 20ºC) | 3.67 | Freeze-dried and powder | CC (on Silica gel) eluted with a solvent gradient from hexane to Et2O More polar fr.: HPLC with DCM-EtOAc (90:10) | IR, UV, MS, (1H and 13C) NMR | 15 | January to December/Piriac, France | [27] |

| 17 (0.01) | |||||||

| Et2O S–L extraction | N.D. | Dried | LC using Silica gel; HPLC of the less polar fr.; Semi-preparative normal-phase HPLC (EtOAc-isooctane, 1:1). | IR, MS, NMR | 23 (0.12) | -/El Jadida, Morocco | [32] |

| 24 (0.08) | |||||||

| 39 (0.01) | |||||||

| DCM S–L extraction, at RT; MeOH S–L extraction | 9.06 | Freeze-dried | Modified Kupchan method: partitioning between (90:10) MeOH-H2O and n-hexane; MeOH-H2O phase: partitioning between (65:35) MeOH-H2O and CHCl3; Fractionation by flash chromatography (on Silica gel), with EtOAc-n-hexane (80:20) DAD and ELSD-HPLC (using a reverse-phase column), eluent gradient (55:45) MeCN-H2O for 13 min, increasing to 100% MeCN in 5 min, maintaining for 20 min (rt = 16.3 min) | IR, 1D and 2D NMR, HRMS, VCD | 14 (0.007) | May/Kilkee, County Clare of Ireland | [50] |

| MeOH S–L extraction DCM S–L extraction | 0.95 | Freeze-dried | VLC (on Silica gel) eluted with cyclohexane-EtOAc (1:2); Semi-preparative reverse phase HPLC (gradient of H2O-MeCN) PTLC over Silica gel (n-hexane-EtOAc, 7:3) | (1H, 13C, APT, COSY, HMBC and HSQC) NMR | 15 (0.002) | May to June/Peniche, Portugal | [51] |

| 23 (9.5 × 10−5) | |||||||

| DCM Soxhlet extraction (9 h) | 3.92 | Freeze-dried and ground | GC-MS | 37 (0.06) | May/Ria de Aveiro, Portugal | [38] | |

| 38 (0.10) | |||||||

| 39 (0.01) | |||||||

| 42 (0.01) | |||||||

| 45 (0.003) | |||||||

| 46 (0.01) |

| Compounds/Crude Extract (Yield) | Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| 12-(S)-hydroxygeranylgeraniol (1) | Antimitotic activity (assay of cytotoxicity activity—inhibition of development of fertilized eggs of the common sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus—EC50 = 18 μg mL−1) | [43] |

| Antifouling activity toward macroalgae spore and zygote development (Sargassum muticum (72.0% ± 2.2% GI)) | [23] | |

| (S)-12-hydroxygeranylgeranic acid (2) | Antimitotic activity (assay of cytotoxicity activity—inhibition of development of fertilized eggs of the common sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus—EC50 = 60 μg mL−1) | [43] |

| (2E,10E,12R)-3,11,15-trimethyl-7-methylenehexadeca-2,10,14-triene-1,6,12-triol (6) | Cytotoxic activity: inhibit in vitro proliferation of pathogenic cells (NSCLC-N6—derived from a human non–small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma) by terminal differentiation. IC50 = 12.3 μg mL−1 | [44] |

| (2E,10E,12R)-3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadeca-2,10,14-triene-1,7,12-triol (7) | Cytotoxic activity: inhibit in vitro proliferation of pathogenic cells (NSCLC-N6—derived from a human non–small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma) by terminal differentiation. IC50 = 9.5 μg mL−1 | [44] |

| Eleganediol (9) | Antibacterial activity (against Bacillus sp. (MIC = 8 μg mL−1) | [23] |

| Antifouling activity toward macroalgal spore and zygote development (Enteromorpha intestinalis (65.2 ± 1.2% GI), Sargassum muticum (81.5 ± 3.4% GI)), and against diatom growth (Amphora coffeaformis (37.3% ± 1.9% GI), Phaeodartylum tricornutum (42.8% ± 1.5% GI), Cylindrotheca closterium (39.5% ± 1.6% GI)) | ||

| Antimitotic activity (assay of cytotoxicity activity—inhibition of development of fertilized eggs of the common sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus—EC50 = 36 μg mL−1) | [43] | |

| Antiadhesion activity (against a strain of Polibacter sp. (EC50 = 63.5 ± 8.3 μg mL−1) and of Paracoccus sp. (EC50 = 103.9 ± 12.8 μg mL−1) | [25] | |

| Antifouling activity (against Balanus amphitrite cyprid (EC50 = 40.37 (11.89 − 62.93, conf. lim. 95%) μg mL−1) | [26] | |

| Toxicity (against Balanus amphitrite nauplius (LC = 7.31 (3.84 − 8.78, conf. lim. 95%) μg mL−1)) | ||

| Antiproliferative activity toward MDA-MB-231 tumor cells (1.8% cell viability at 100 μg mL−1) | [48] | |

| Bifurcane (10) | Antimitotic activity (assay of cytotoxicity activity - inhibition of development of fertilized eggs of the common sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus – EC50 = 12 μg mL−1). | [29] |

| Antiproliferative activity toward MDA-MB-231 tumor cells (2.9% cell viability at 100 μg mL−1) | [48] | |

| Bifurcatriol (14) | Antimalarial activity (against resistant K1 strain of the malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum – IC50 = 0.65 ± 0.05 μg mL−1) | [50] |

| Antiprotozoal activity: Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (IC50 = 11.8 ± 0.01 μg mL−1), Trypanosoma cruzi (IC50 = 47.8 ± 0.59 μg mL−1), Leishmania donovani (IC50 = 18.8 ± 0.12 μg mL−1)) | ||

| Cytotoxicity against the L6 rat myoblast cell line (IC50 = 56.6 ± 0.004 μg mL−1) | ||

| Eleganolone (15) | Antimicrobial activity (against Mycobacterium smegmatis (75 μg mL−1), Bacillus subtilis (2.5 mg mL−1), Mycobacterium aquae (400 μg mL−1), Mycobacterium ranae (100 μg mL−1), Mycobacterium xenoqui (200 μg mL−1), Mycobacterium avium (100 μg mL−1)) | [20] |

| Antiprotozoal activity (against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (IC50 = 13.7 μg mL−1), Trypanosoma cruzi (IC50 = 17.7 μg mL−1), Plasmodium falciparum, IC50 = 2.6 μg mL−1 (SI = 21.6)) | [21] | |

| In vitro antiplasmodial activity (against Plasmodium falciparum 7G8 strain – antimalarial activity – In fraction: 47% of growth inhibition at 10 μg mL−1) | [22] | |

| Antibacterial activity (against Bacillus sp. (MIC = 8 μg mL−1) | [23] | |

| Anti-adhesion activity (against a strain of Polibacter sp. (EC50 = 58.4 ± 1.7 μg mL−1) and of Paracoccus sp. (EC50 = 40.3 ± 13.5 μg mL−1) | [25] | |

| Antifouling activity (against Balanus amphitrite cyprid (EC50 = 2.14 (0.88 − 3.9, conf. lim 95%) μg mL−1) | [26] | |

| Toxicity (against Balanus amphitrite nauplius (LC = 3.48 (2.53 − 4.52, conf. lim 95%) μg mL−1)) | ||

| Cytotoxicity (against mouse fibroblast cell line (L929), IC50 = 22 μg mL−1) | [30] | |

| Antioxidant potential (ORAC—1663.83 ± 25.35 µmol TE g−1 of compound, FRAP—8341.18 ± 177.72 µM FeSO4 g−1 compound) | [51] | |

| (6E,10E,14E)-16-hydroxy-2,6,10,14-tetramethylhexadeca-2,6,10,14-tetraen-4-one (21) | Cytotoxicity (against mouse fibroblast cell line (L929), IC50 = 18 μg mL−1) | [30] |

| (10E,14E)-16-hydroxy-2,10,14-trimethyl-6-methylenehexadeca-2,10,14-triene-4,7-dione (22) | Antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus, MIC = 8 μg mL−1) and marine fungi (MIC = 8 μg mL−1) (such as Corollospora maritima, Lulworthia sp., and Dendryphiella salina) | [23] |

| Eleganolal (23) | Antioxidant potential (ORAC—667.48 ± 10.96 µmol TE g−1 of compound, FRAP—8635.37 ± 389.54 µM FeSO4 g−1 compound) | [51] |

| (6E,14E)-16-hydroxy-2,6,14-trimethyl-10-methylenehexadeca-2,6,14-triene-4,11-dione (25) | Antimicrobial activity against gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus, MIC = 8 μg mL−1) and marine fungi (MIC = 8 μg mL−1) (such as Corollospora maritima, Lulworthia sp., and Dendryphiella salina) | [23] |

| Eleganolonebutenolide (32) | Cytotoxicity (against mouse fibroblast cell line (L929), IC50 = 27 μg mL−1) | [30] |

| 14,15-dihydro-eleganonic acid (33) | Cytotoxicity (against mouse fibroblast cell line (L929), IC50 = 20 μg mL−1) | [30] |

| Geranylgeraniol (39) | Antifouling activity—macroalgal spore and zygote development (Enteromorpha intestinalis (67.3 ± 2.1% GI); Ulva lactuca (83.1% ± 3.4% GI)) and inhibition of adhesion of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis (77.0% ± 2.8% IPA) | [23] |

| Bifurcanol (41) | Antimitotic activity (assay of cytotoxicity activity—inhibition of development of fertilized eggs of the common sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus—EC50 = 4 μg mL−1). | [43] |

| Cytotoxicity (against mouse fibroblast cell line (L929), IC50 = 24 μg mL−1). | [30] | |

| DCM extract (3.92 ± 0.09% (w/w)) | Antioxidant activity (in vitro: DPPH assay: IC50 = 365.57 ± 10.04 μg mL−1, ABTS assay: IC50 = 116.25 ± 2.54 μg mL−1) | [38] |

| Anti-inflammatory activity (NO production (% of LPS): 6% at 50 μg mL−1) | ||

| Antibacterial activity (against both gram-positive (Staphylococcus aureus ATCC®6538 (MIC = 1024 μg mL−1), Staphylococcus aureus ATCC®43300 (MIC = 2048 μg mL−1)) and gram-negative (Escherichia coli ATCC®25922 (MIC = 2048 μg mL−1)) strains) | ||

| Synergistic effects with antibiotic:Against S. aureus ATCC®6538 (Gent (MIC = 32 μg mL−1); Gent + Ext (MIC =16 μg mL−1); Tetra (MIC = 16 μg mL−1); Tetra + Ext (MIC = 8 μg mL−1))Against S. aureus ATCC®43300 (Rif (MIC = 16 μg mL−1); Rif + Ext (MIC < 2 μg mL−1); Gent (MIC > 256 μg mL−1); Gent+Ext (MIC = 16 μg mL−1); Tetra (MIC > 256 μg mL−1); Tetra + Ext (MIC < 2 μg mL−1))Against E. coli ATCC®25922 (Rif (MIC = 32 μg mL−1); Rif + Ext (MIC = 16 μg mL−1); Gent (MIC > 256 μg mL−1); Gent+Ext (MIC < 2 μg mL−1); Tetra (MIC = 18 μg mL−1); Tetra + Ext (MIC < 2 μg mL−1)) | ||

| EtOAc extract * | Antiprotozoal activity (against erythrocytes infected by a resistant K1 strain of Plasmodium falciparum (100% of GI at 9.7 μg mL−1), Trypanosoma cruzi trypamastigostes (78% of GI at 9.7 μg mL−1), and Leishmania donovani amastigotes (100% of GI at 9.7 μg mL−1), IC50 = 3.8 μg mL−1) | [35] |

| Cytotoxicity activity (against L6 cells, rat skeletal myoblasts, IC50 = 6 μg mL−1) | ||

| EtOAc:MeOH (1:1) soluble extract* | Anti-tubercular activity (against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, MIC = 64.0 μg mL−1) | [61] |

| Antiprotozoal activity (against Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense (IC50 = 1.9 μg mL−1), Trypanosoma cruzi (IC50 = 34.7 μg mL−1), and Leishmania. donovani (IC50 = 6.4 μg mL−1)) | ||

| Cytotoxicity (IC50 = 32.7 μg mL−1) | ||

| DCM-MeOH ASE extract* | Antioxidant activity (DPPH assay: EC50 = 0.56 ± 0.00 mg mL−1, reducing activity: 90.97% at 500 mg L−1, β-carotene-linoleic acid system assay: 76.13% ± 0.55% of inhibition at 500 mg L−1, TPC 0.96% dw) | [8] |

| Antitumoral activity (tested with Daudi (Human Burkitt’s lymphoma), K562 (Human chronic myelogenous leukemia) (~40% of viable cells), and Jurkat (Human leukemic T cell lymphoblast) (~20% of viable cells) cells) | ||

| MeOH clean and enrich extract * | Antioxidant activity (TPC: 129.17 ± 0.002 mg GAE g−1 ext, ORAC: 3151.35 ± 119.33 μmol TE g−1 ext, DPPH: IC50 = 58.82 (50.65 − 68.31) μg mL−1) | [54,55] |

| Antimicrobial activity (against Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (11.3 ± 1.5 mm ZI), Escherichia coli ATCC 105366 (7.0 ± 0.0 mm ZI), Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 (6.7 ± 0.6 mm ZI), Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 (7.0 ± 0 mm ZI), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 9763 (IC50 = 26.68 μg mL−1)) | ||

| Antitumor activity: cell proliferation inhibition (tested in 2 in vitro carcinoma models, a human colorectal adeno-carcinoma (Caco-2) (IC50 = 437.1 (266.0 − 718.1) μg mL−1), and a human hepatocellular liver cancer (HepG-2) (IC50 = 252.0 (162.0 − 392.2) μg mL−1)) | ||

| DCM extract * | Antioxidant activity (TPC: 43.21 ± 0.043 mg GAE g−1 ext, ORAC: 589.98 ± 7.33 μmol TE g−1 ext, DPPH: IC50 = 344.70 (246.10 − 482.80) μg mL−1) | [54,55] |

| Antimicrobial activity (against gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 (8.3 ± 1.2 mm ZI), Escherichia coli ATCC 105366 (8.3 ± 0.6 mm ZI)), and Saccharomyces cerevisiae ATCC 9763 (IC50 = 17.06 μg mL−1)) | ||

| Antitumor activity: cell proliferation inhibition and cytotoxicity (tested in 2 in vitro carcinoma models, a human colorectal adeno-carcinoma (Caco-2) (IC50 = 82.31 (54.7 − 123.8) μg mL−1) (IC50 = 90.09 (70.82 − 114.6) μg mL−1), and a human hepatocellular liver cancer (HepG-2) (IC50 = 95.63 (69.66 − 131.3) μg mL−1) (IC50 = 123.9 (95.47 − 160.8) μg mL−1)) | ||

| Et2O extract(2.2%–2.9% of dw) | Antifouling activity (against 2 marine bacteria, Cobetia marina (MIC between 12.2 ± 0.4 to 26.3 ± 1.3 μg mL−1) and Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis (MIC between 6.5 ± 0.6 to 15.5 ± 0.8 μg mL−1), and cypris larvae of the barnacle, Balanus amphitrite (EC50 = 10 μg mL−1)) | [36] |

| MeOH clean and enriched extract(6.92% of dw) | Anti-proliferative effect (of well-differentiated pathologic cells, such as a human non–small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma line (NSCLC-N6) (IC50 = 4 μg mL−1), by terminal differentiation) | [37] |

| EtOAc extract(4.80% of dw) | Antiprotozoal activity (against Trypanosomas brucei rhodesiense trypomastigotes—crude extracts and the most active fraction) | [21] |

| Et2O extract | Antifouling activity (against Balanus amphitrite cyprid (EC50 = 0.43 (0.88 − 1.26, conf. lim. 95%) μg mL−1) | [26] |

| Toxicity (against Balanus amphitrite nauplius (LC = 0.64 (0.26 − 1.14, conf. lim. 95%) μg mL−1)) | ||

| Et2O extract(3.15% of dw) | Antifouling activity toward macroalgal spore and zygote development (Ulva lactuca (78.7% ± 2.8% GI)), against diatom growth (Amphora coffeaformis (83.9% ± 4.2% GI), Phaeodartylum tricornutum (86.2% ± 3.4% GI), Cylindrotheca closterium (69.2% ± 2.4% GI)), and inhibition of adhesion of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis (80.6% ± 2.3% IPA) | [23] |

| Fraction of DCM extract(0.95% of dw) | Neuroprotective effect (prevent changes in mitochondrial potential (218.10% ± 14.87% of control), reduction of H2O2 levels production (204.50% ± 15.12% of control), revert neurotoxic effect on cell viability to about 20%–25%). | [51] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pais, A.C.S.; Saraiva, J.A.; Rocha, S.M.; Silvestre, A.J.D.; Santos, S.A.O. Current Research on the Bioprospection of Linear Diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata: From Extraction Methodologies to Possible Applications. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100556

Pais ACS, Saraiva JA, Rocha SM, Silvestre AJD, Santos SAO. Current Research on the Bioprospection of Linear Diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata: From Extraction Methodologies to Possible Applications. Marine Drugs. 2019; 17(10):556. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100556

Chicago/Turabian StylePais, Adriana C.S., Jorge A. Saraiva, Sílvia M. Rocha, Armando J.D. Silvestre, and Sónia A.O. Santos. 2019. "Current Research on the Bioprospection of Linear Diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata: From Extraction Methodologies to Possible Applications" Marine Drugs 17, no. 10: 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100556

APA StylePais, A. C. S., Saraiva, J. A., Rocha, S. M., Silvestre, A. J. D., & Santos, S. A. O. (2019). Current Research on the Bioprospection of Linear Diterpenes from Bifurcaria bifurcata: From Extraction Methodologies to Possible Applications. Marine Drugs, 17(10), 556. https://doi.org/10.3390/md17100556