Time Course Exo-Metabolomic Profiling in the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) for Identification of Growth Phase-Dependent Biomarkers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Experimental Design and Biological Metadata

2.1.1. Assessment of Algal Growth and the Bacterial Community

2.1.2. Nutrient Depletion in Ulva Culture Medium (UCM)

2.1.3. Inducibility of Gametogenesis and Production of the Swarming Inhibitor

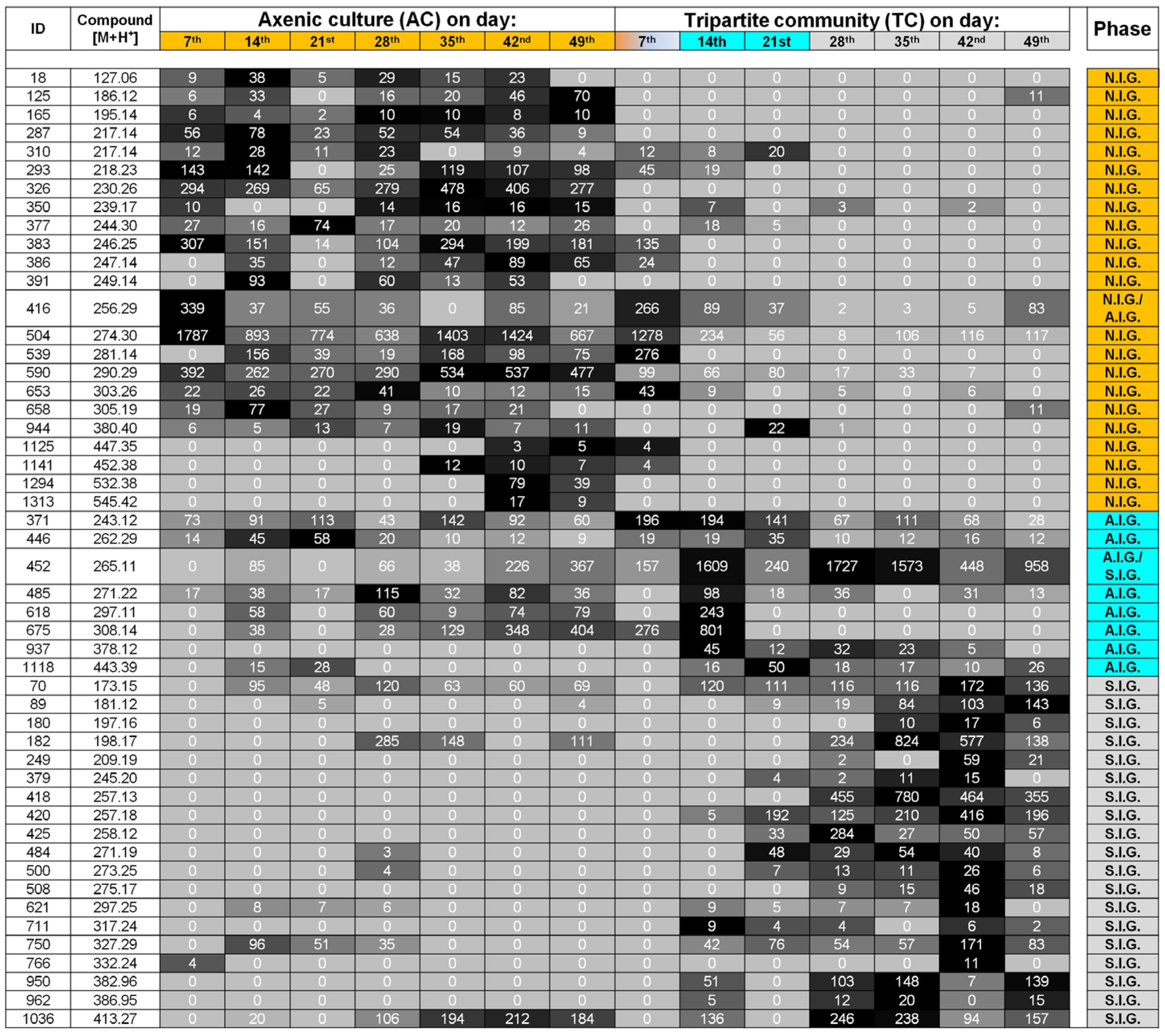

2.2. Data Analysis and Identification of Biomarkers in the Chemosphere via GC-MS

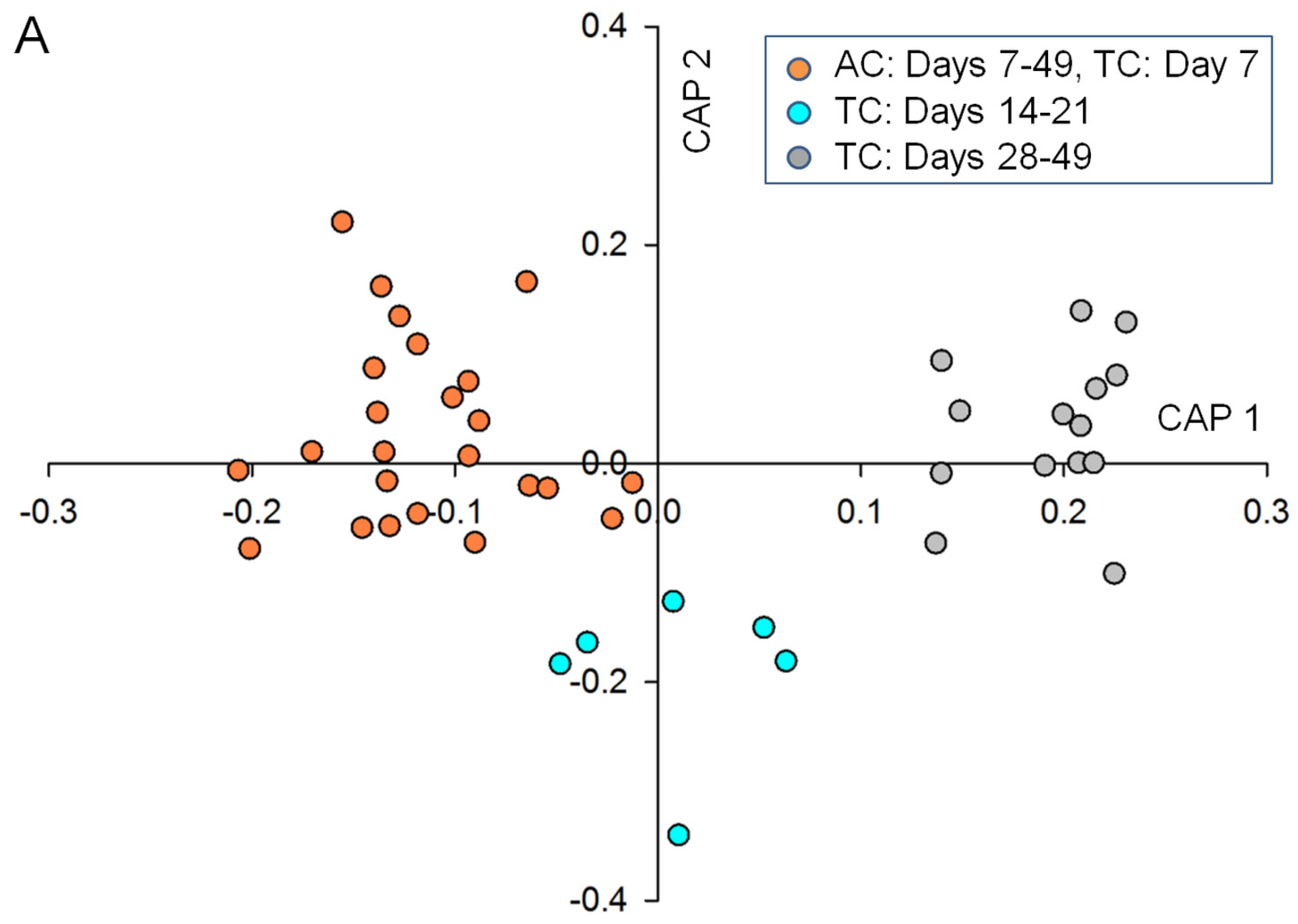

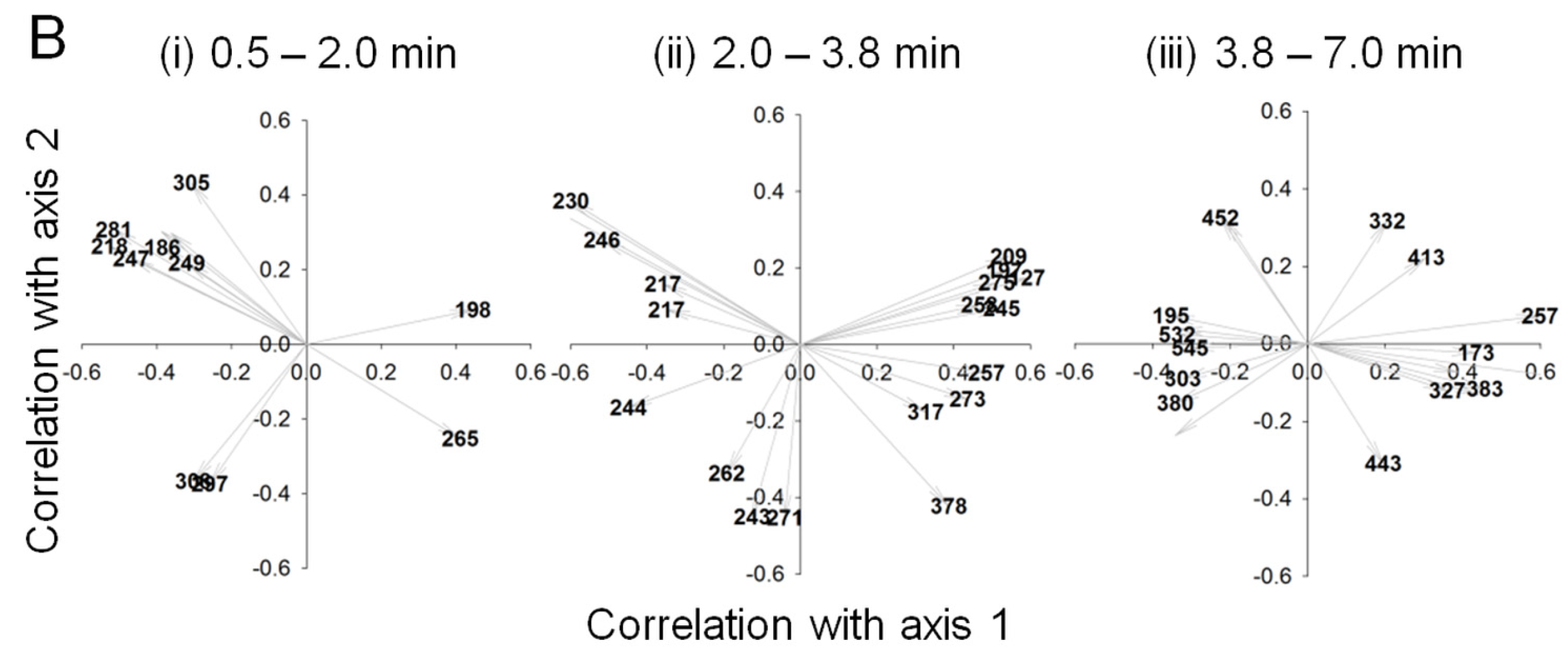

2.3. Data Analysis and Identification of Important Biomarkers in the Chemosphere via LC-MS Analysis

2.4. Biological Interpretation and Hypothesis Generation: Metabolites Shaping the Mutualistic Interaction of Ulva and Associated Bacteria

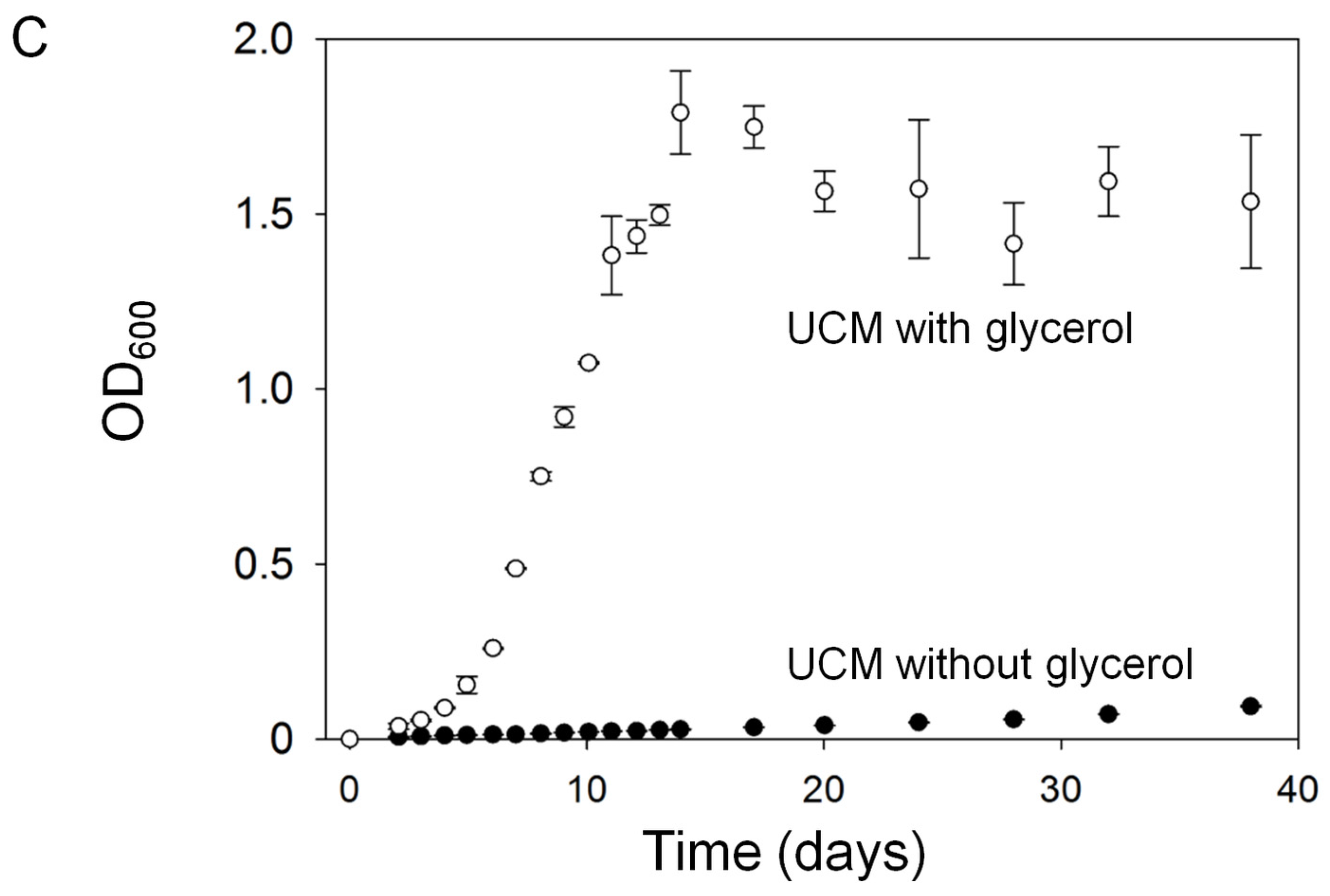

2.4.1. Ulva Provides Glycerol as a Potential Carbon Source for Bacterial Growth

2.4.2. Organic Acids Might Increase the Bioavailability of Essential Trace Metals

2.4.3. Amino Acid-Mediated Signaling between Ulva and Bacteria

2.4.4. Halogenated Phenolic Substances Might Act as Deterrents in Ulva’s Chemosphere

2.5. The “Known Unknowns”

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Cultivation of U. mutabilis and Bacteria in Bioreactors

3.2. Sample Collection and Storage

3.3. Determination of Nutrients, Biota Data and Growth

3.3.1. Nitrate and Phosphate

3.3.2. Life Cycle Regulating Factors

3.3.3. Monitoring of Ulva’s Growth

3.3.4. DNA Extraction and PCR Amplification for Monitoring Axenicity and Bacterial Growth

3.4. Sample Preparation and GC-MS Analysis

3.4.1. Derivatization

3.4.2. GC-ToF-MS Parameters

3.5. Sample Preparation and LC-MS Analysis

3.6. Data Processing

3.6.1. GC-MS

3.6.2. LC-MS

3.7. Statistical Analysis

3.8. Annotation of Metabolites Acquired by GC-MS Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC | axenic culture |

| A.I.G. | artificially inducible gametogenesis |

| CAP | canonical analysis of principle coordinates |

| DGGE | denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis |

| DRE | dynamic range extension |

| EI | electron impact |

| ESI | electrospray ionization |

| GC | gas chromatography |

| IAA | indole-3-acetic acid |

| LC | liquid chromatography |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| N.I.G. | non-inducible gametogenesis |

| OD | optical density |

| PCoA | principal coordinate analysis |

| PCR | poly chain reaction |

| SI | sporulation inhibitor |

| S.I.G. | spontaneously inducible gametogenesis |

| SFA SWI | Saturated fatty acids swarming inhibitor |

| TBP | 2,4,6-tribromophenol |

| TC | tripartite community |

| ToF | time-of-flight mass spectrometer |

| UCM | Ulva culture medium |

| UHPLC | ultra-high pressure liquid chromatography |

| UR | utilization rate |

References

- Little, A.E.F.; Robinson, C.J.; Brook Peterson, S.; Raffa, K.F.; Handelsman, J. Rules of engagement: Interspecies interactions that regulate microbial communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2008, 62, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azam, F.; Malfatti, F. Microbial structuring of marine ecosystems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 5, 782–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jewett, M.C.; Hofmann, G.; Nielsen, J. Fungal metabolite analysis in genomics and phenomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006, 17, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roessner, U.; Bowne, J. What is metabolomics all about? BioTechniques 2009, 46, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsufyani, T. Metabolite Profiling of the Chemosphere of the Macroalga Ulva (Ulvales, Chlorophyta) and Its Associated Bacteria Dissertation; Friedrich Schiller University Jena: Jena, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goecke, F.; Labes, A.; Wiese, J.; Imhoff, J.F. Chemical interactions between marine macroalgae and bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 409, 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint, I.; Tait, K.; Wheeler, G. Cross-kingdom signalling: Exploitation of bacterial quorum sensing molecules by the green seaweed Ulva. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2007, 362, 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichard, T. Exploring bacteria-induced growth and morphogenesis in the green macroalga order Ulvales (Chlorophyta). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoerner, M.; Wichard, T.; Bachhuber, T.; Stratmann, J.; Oertel, W. Growth and thallus morphogenesis of Ulva mutabilis (Chlorophyta) depends on a combination of two bacterial species excreting regulatory factors. J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1433–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, L.; Aberg, S. Morphogenetic effects of phenylacetic and p-OH-phenylacetic acid on green-alga Enteromorpha compressa (L.) grev in axenic culture. Z. Pflanzenphysiol. 1978, 88, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueneberg, J.; Engelen, A.H.; Costa, R.; Wichard, T. Macroalgal morphogenesis induced by waterborne compounds and bacteria in coastal seawater. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Føyn, B. Über die Sexualität und den Generationswechsel von Ulva mutabilis. Arch. Protistenkd. 1958, 102, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Føyn, B. Geschlechtskontrollierte Vererbung bei der marinen Grünalge Ulva mutabilis. Arch. Protistenkd. 1959, 104, 236–253. [Google Scholar]

- Løvlie, A. Genetic control of division rate and morphogenesis in Ulva mutabilis Føyn. C. R. Trav. Lab. Carlsberg 1964, 34, 77–168. [Google Scholar]

- Oertel, W.; Wichard, T.; Weissgerber, A. Transformation of Ulva mutabilis (Chlorophyta) by vector plasmids integrating into the genome. J. Phycol. 2015, 51, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wichard, T.; Charrier, B.; Mineur, F.; Bothwell, J.H.; De Clerck, O.; Coates, J.C. The green seaweed Ulva: A model system to study morphogenesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, N.; Liang, C.; Mou, S.; Fan, X.; Xu, J.; Xu, D.; Zhuang, Z. De novo sequencing and analysis of the Ulva linza transcriptome to discover putative mechanisms associated with its successful colonization of coastal ecosystems. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratmann, J.; Paputsoglu, G.; Oertel, W. Differentiation of Ulva mutabilis (Chlorophyta) gametangia and gamete release are controlled by extracellular inhibitors. J. Phycol. 1996, 32, 1009–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesty, E.F.; Kessler, R.W.; Wichard, T.; Coates, J.C. Regulation of gametogenesis and zoosporogenesis in Ulva linza (Chlorophyta): Comparison with Ulva mutabilis and potential for laboratory culture. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsen, G.; Nordby, O. Sporulation inhibiting substance from vegetative thalli of green alga Ulva mutabilis Føyn. Planta 1975, 125, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Muyzer, G.; Teske, A.; Wirsen, C.O.; Jannasch, H.W. Phylogenetic-relationships of Thiomicrospira species and their identification in deep-sea hydrothermal vent samples by denaturing gradient gel-electrophoresis of 16S rDNA fragments. Arch. Microbiol. 1995, 164, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneed, J.M.; Pohnert, G. The green alga Dicytosphaeria ocellata and its organic extracts alter natural bacterial biofilm communities. Biofouling 2011, 27, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naldi, M.; Viaroli, P. Nitrate uptake and storage in the seaweed Ulva rigida C. Agardh in relation to nitrate availability and thallus nitrate content in a eutrophic coastal lagoon (Sacca di Goro, Po River Delta, Italy). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2002, 269, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichard, T.; Oertel, W. Gametogenesis and gamete release of Ulva mutabilis and Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta): Regulatory effects and chemical characterization of the “swarming inhibitor”. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, B.P.; Northen, T.R. Dealing with the unknown: Metabolomics and metabolite atlases. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2010, 21, 1471–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, J.L.; Cleven, C.D.; Brown, S.D. Identification of “Known Unknowns” utilizing accurate mass data and chemical abstracts service databases. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 22, 348–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, M.J.; Robinson, J. Generalised discriminant analysis based on distances. Aust. N. Z. J. Stat. 2003, 45, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, T.R.; Hnilicka, K.; Dziedzic, A.; Desplats, P.; Belas, R. Chemotaxis of Silicibacter sp. strain TM1040 toward dinoflagellate products. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 4692–4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, T.; Stasolla, C.; Yeung, E.C.; de Klerk, G.-J.; Roberts, A.; George, E.F. The Components of Plant Tissue Culture Media II: Organic Additions, Osmotic and pH Effects, and Support Systems in Plant Propagation by Tissue Culture; George, E.F., Hall, M.A., De Klerk, G.-J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 115–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ojima, K.; Ohira, K. The exudation and characterization of iron-solubilizing compounds in a rice cell suspension culture. Plant Cell Physiol. 1980, 21, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar]

- Wichard, T. Identification of metallophores and organic ligands in the chemosphere of the marine macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) and at land-sea interfaces. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.C.; Decker, A.M.; Chaney, R.L. Metal complexation in xylem fluid: I. chemical composition of tomato and soybean stem exudate. Plant Physiol. 1981, 67, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruckner, C.G.; Rehm, C.; Grossart, H.-P.; Kroth, P.G. Growth and release of extracellular organic compounds by benthic diatoms depend on interactions with bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nilsson, C.; Sundbäck, K. Amino acid uptake in natural microphytobenthic assemblages studied by microautoradiography. Hydrobiologia 1996, 332, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myklestad, S.; Holm-Hansen, O.; Vårum, K.M.; Volcani, B.E. Rate of release of extracellular amino acids and carbohydrates from the marine diatom Chaetoceros affinis. J. Plankton Res. 1989, 11, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.A.; Hmelo, L.R.; van Tol, H.M.; Durham, B.P.; Carlson, L.T.; Heal, K.R.; Morales, R.L.; Berthiaume, C.T.; Parker, M.S.; Djunaedi, B.; et al. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature 2015, 522, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etahiri, S.; El Kouri, A.K.; Bultel-Ponce, V.; Guyot, M.; Assobhei, O. Antibacterial bromophenol from the marine red alga Pterosiphonia complanala. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 749–752. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.; Fan, X.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Niu, R.; Tseng, C.K. Antibacterial bromophenols from the marine red alga Rhodomela confervoides. Phytochemistry 2003, 62, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hansen, P.E.; Lin, X. Bromophenols in Marine algae and Their Bioactivities. Mar. Drugs 2011, 9, 1273–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.-Y.; Agatsuma, Y.; Taniguchi, K. Inhibitory effect of 2,4-dibromophenol and 2,4,6-tribromophenol on settlement and survival of larvae of the Japanese Abalone Haliotis discus hannai Ino. J. Shellfish Res. 2009, 28, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Song, F.H.; Fan, X.; Fang, N.Q.; Shi, J.G. A novel bromophenol from marine red alga Symphyocladia latiuscula. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2009, 45, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.Y.; Ma, W.C.J.; Ang, P.O.; Kim, J.-S.; Chen, F. Seasonal variations of bromophenols in brown algae (Padina arborescens, Sargassum siliquastrum, and Lobophora variegata) collected in Hong Kong. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 2619–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibata, T.; Miyasaki, T.; Miyake, H.; Tanaka, R.; Kawaguchi, S. The Influence of phlorotannins and bromophenols on the feeding behavior of marine herbivorous gastropod turbo cornutus. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodin, C.; Whitfield, F.B. Biosynthesis of bromophenols in marine algae. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flodin, C.; Helidoniotis, F.; Whitfield, F.B. Seasonal variation in bromophenol content and bromoperoxidase activity in Ulva lactuca. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quanbeck, S.M.M.; Brachova, L.; Campbell, A.A.; Guan, X.; Perera, A.; He, K.; Rhee, S.Y.; Bais, P.; Dickerson, J.; Dixon, P.; et al. Metabolomics as a hypothesis-generating functional genomics tool for the annotation of Arabidopsis thaliana genes of “unknown function”. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidoudez, C.; Pohnert, G. Comparative metabolomics of the diatom Skeletonema marinoi in different growth phases. Metabolomics 2012, 8, 654–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Z.; Fischer, C.J. A simplified resorcinol method for direct spectrophotometric determination of nitrate in seawater. Mar. Chem. 2006, 99, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T.R.; Maita, L.; Lalli, M. A Manual of Chemical and Biological Methods of Seawater Analysis; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Miyamura, S. Cytoplasmic inheritance in green algae: Patterns, mechanisms and relation to sex type. J. Plant Res. 2010, 123, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüning, K. Seaweeds. Their Environment, Biogeography, and Ecophysiology; Wiley-Interscience Publication: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Olischlaeger, M.; Bartsch, I.; Gutow, L.; Wiencke, C. Effects of ocean acidification on growth and physiology of Ulva lactuca (Chlorophyta) in a rockpool-scenario. Phycol. Res. 2013, 61, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyzer, G.; Dewaal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction amplified genes coding for 16S ribosomal RNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barofsky, A.; Simonelli, P.; Vidoudez, C.; Troedsson, C.; Nejstgaard, J.C.; Jakobsen, H.H.; Pohnert, G. Growth phase of the diatom Skeletonema marinoi influences the metabolic profile of the cells and the selective feeding of the copepod Calanus spp. J. Plankton Res. 2010, 32, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barofsky, A.; Vidoudez, C.; Pohnert, G. Metabolic profiling reveals growth stage variability in diatom exudates. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 2009, 7, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratkowsky, D.A.; Gates, G.M. Generalised canonical correlations analysis for explaining macrofungal species assemblages. Australas. Mycol. 2008, 27, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ratkowsky, D.A. Visualising macrofungal species assemblage compositions using canonical discriminant analysis. Australas. Mycol. 2007, 26, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.; Willis, T. Canonical analysis of principal coordinates: A useful method of constrained ordination for ecology. Ecology 2003, 84, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, C.E.; Hyndes, G.A.; Wang, S.F. Differentiation of benthic marine primary producers using stable isotopes and fatty acids: Implications to food web studies. Aquat. Bot. 2010, 93, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölling, C.; Fiehn, O. Metabolite profiling of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii under nutrient deprivation. Plant Physiol. 2005, 139, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alsufyani, T.; Weiss, A.; Wichard, T. Time Course Exo-Metabolomic Profiling in the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) for Identification of Growth Phase-Dependent Biomarkers. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15010014

Alsufyani T, Weiss A, Wichard T. Time Course Exo-Metabolomic Profiling in the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) for Identification of Growth Phase-Dependent Biomarkers. Marine Drugs. 2017; 15(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlsufyani, Taghreed, Anne Weiss, and Thomas Wichard. 2017. "Time Course Exo-Metabolomic Profiling in the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) for Identification of Growth Phase-Dependent Biomarkers" Marine Drugs 15, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15010014

APA StyleAlsufyani, T., Weiss, A., & Wichard, T. (2017). Time Course Exo-Metabolomic Profiling in the Green Marine Macroalga Ulva (Chlorophyta) for Identification of Growth Phase-Dependent Biomarkers. Marine Drugs, 15(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/md15010014