1. Introduction

With the rapidly aging population, osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures (OVCFs) have become a major public health burden. While the majority of these fractures heal with conservative management, a subset of patients experiences progressive vertebral collapse during the acute phase [

1,

2]. Such progressive collapse is clinically significant as it can lead to severe kyphotic deformity, persistent back pain, and potential neurological deficits due to bone fragment retropulsion [

3]. Furthermore, failure of early mechanical stabilization may result in osteonecrosis, known as Kümmell’s disease, which often necessitates challenging surgical reconstruction [

4]. Therefore, preventing excessive vertebral height loss in the early post-injury period is a primary goal of clinical management.

To prevent secondary fractures and promote healing, pharmacological intervention is essential. According to current guidelines [

5], anabolic agents such as teriparatide (TPTD) and romosozumab (RM) are recommended for patients at high risk of fracture. Unlike antiresorptive agents, which primarily inhibit bone turnover, anabolic agents stimulate osteoblastic activity and have been shown to accelerate callus formation and bone union in clinical trials [

6]. Theoretically, this rapid biological healing could provide early structural stability, provided that pharmacological management accounts for the distinct biological mechanisms and onset speeds of action for various agents [

1,

5,

6]. For instance, romosozumab exerts a dual effect by rapidly increasing bone formation and decreasing resorption through sclerostin inhibition [

5,

6]. While teriparatide primarily stimulates osteoblastic activity to promote union [

5,

6], potent antiresorptives such as denosumab provide a rapid and sustained reduction in bone turnover [

1,

5]. Understanding these varying biological timelines is essential when evaluating acute-phase structural stability and preventing delayed complications like Kümmell’s disease [

4] within the initial 3-month post-fracture window. Consequently, there is a growing clinical expectation that initiating potent anabolic therapy immediately after an OVCF diagnosis might prevent further deformity. However, a significant clinical gap exists regarding whether such early pharmacological intervention can meaningfully alter the rapid mechanical failure of a fractured vertebra. While potent agents offer biological plausibility by accelerating bone formation, and potentially enhancing bone strength, the mechanical reality—dominated by fracture instability—may dictate the degree of collapse before these pharmacological effects can fully manifest [

7].

Therefore, it remains controversial whether these pharmacological benefits translate into the prevention of radiographic collapse during the acute phase (the initial 3 months). Most pivotal trials have focused on long-term bone mineral density (BMD) improvements or fracture risk reduction over 1 to 2 years, leaving a gap in evidence regarding short-term structural outcomes [

8,

9]. Moreover, in the acute setting, mechanical factors—such as the initial fracture morphology—may play a more dominant role than biological healing. For instance, Sugita et al. classified OVCFs based on initial imaging and suggested that specific “unstable” morphologies are predestined for poor prognosis regardless of standard treatment [

10]. Despite this, few studies have directly compared the efficacy of various osteoporosis medications, including both anabolic and antiresorptive agents, against the natural course of vertebral collapse while simultaneously accounting for these baseline mechanical risk factors.

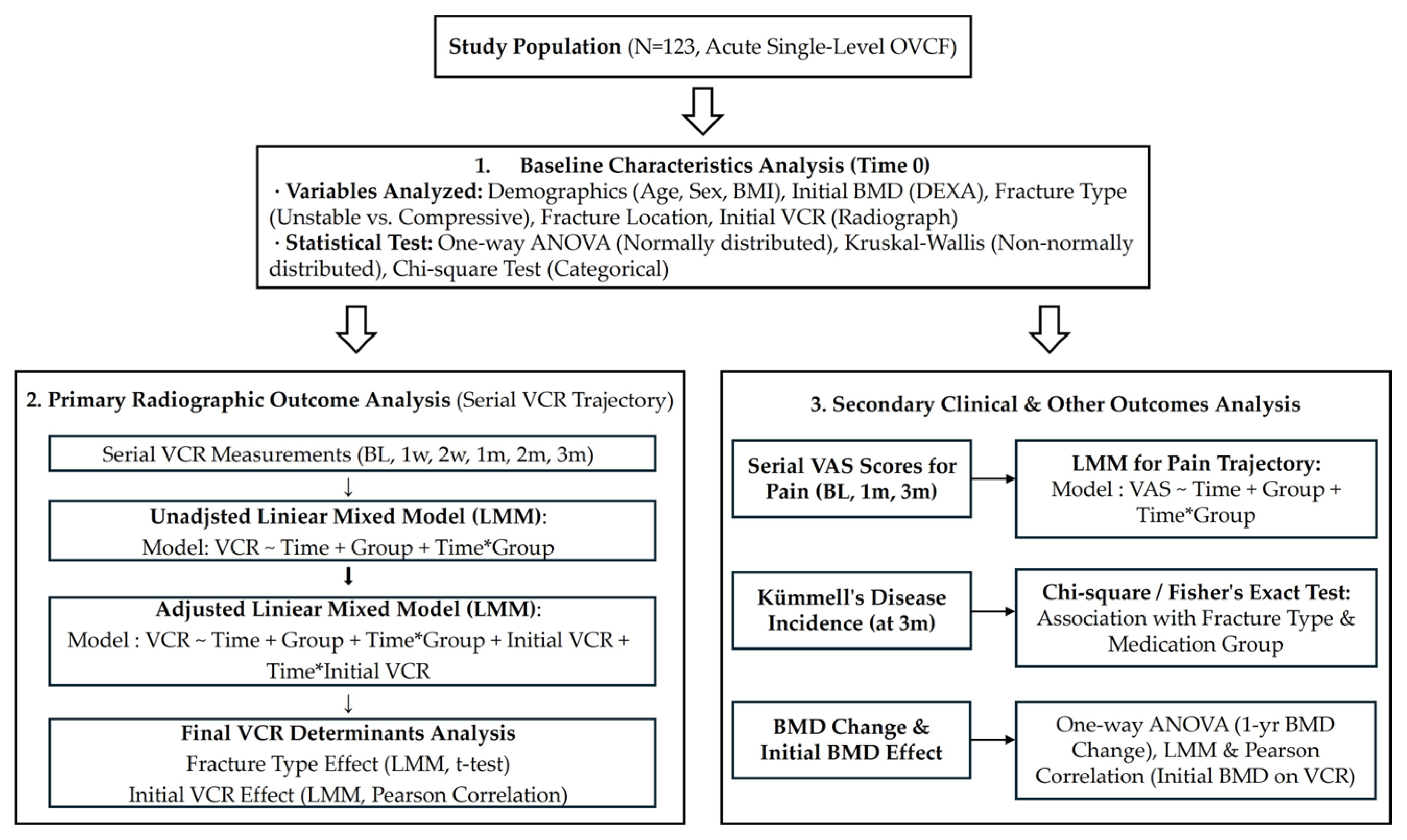

Therefore, the objective of this study was to investigate the factors influencing the progression of vertebral collapse during the initial 3-month acute phase of OVCF. We aimed to compare the radiographic protective effects of three distinct osteoporosis medications—TPTD, RM, and denosumab (DMAB)—against a control group. Furthermore, we sought to determine the relative contribution of pharmacological intervention versus baseline structural characteristics, specifically fracture morphology and initial compression severity, in determining the trajectory of vertebral height loss. Distinct from studies focused on long-term fracture prevention, this research specifically utilizes a 3-month observation window to evaluate whether pharmacological intervention can mitigate the precipitous mechanical collapse that typically occurs before significant biological bone remodeling can take place.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 123 patients were included in the final analysis and were stratified into four treatment groups: the control group (n = 26), the DMAB group (n = 35), the TPTD group (n = 30), and the RM group (n = 32).

There were no statistically significant differences in baseline demographic data—including age, sex, height, weight, initial spine BMD, fracture group, and fracture location—among the four medication groups (

p > 0.05 for all comparisons) (

Table 1). These findings confirm that the study groups were homogeneous, allowing for a comparable analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics by medication group.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics by medication group.

|

Variable

|

RM (n = 32)

|

TPTD (n = 30)

|

DMAB

(n = 35)

|

Control

(n = 26)

| p-Value

| SMD ***

|

|---|

| Age (years)

| 73.19 ± 7.35

| 75.63 ± 8.76

| 78.17 ± 8.39

| 74.38 ± 10.79

| 0.1231

| 0.55

|

| Height (cm)

| 157.45 ± 6.86

| 156.00 ± 5.36

|

155.20 ± 7.22

|

159.00 ± 8.16

|

0.0627

|

0.51

|

|

Weight (kg)

|

59.10 ± 9.48

|

60.07 ± 7.78

|

56.30 ± 9.65

|

58.83 ± 9.48

|

0.4135

|

0.24

|

|

Initial BMD (Spine T-score)

|

−2.46 ± 1.04

|

−2.39 ± 1.02

|

−2.85 ± 0.93

|

−2.63 ± 0.98

|

0.2097

|

0.46

|

|

Sex (N, %)

| | | | |

0.2251

|

0.31

|

|

Male

|

5 (15.6%)

|

1 (3.3%)

|

3 (8.6%)

|

5 (19.2%)

| | |

|

Female

|

27 (84.4%)

|

29 (96.7%)

|

32 (91.4%)

|

21 (80.8%)

| | |

|

Fracture Group (N, %) *

| | | | |

0.2667

|

0.41

|

|

Compressive

|

26 (81.2%)

|

18 (60.0%)

|

26 (74.3%)

|

17 (65.4%)

| | |

|

Unstable

|

6 (18.8%)

|

12 (40.0%)

|

9 (25.7%)

|

9 (34.6%)

| | |

|

Fracture Location (Level) **

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

N/A

|

0.3739

| |

|

Initial VCR (%)

†

| 14.73 ± 10.21 | 15.52 ± 9.84 | 25.14 ± 14.28 | 21.35 ± 13.56 |

0.003

|

0.84

|

Table 2.

Linear mixed model analysis of VCR progression: unadjusted versus adjusted models.

Table 2.

Linear mixed model analysis of VCR progression: unadjusted versus adjusted models.

| Predictor | Unadjusted Model

(p-Value) a | Adjusted Model (β [95% CI]) b | p-Value |

|---|

| Time (Natural Progression) | <0.001 * | | <0.001 * |

| Medication Interaction c | | | |

| Time × DMAB | 0.010 * | −0.339 [−1.43, 0.75] | 0.544 |

| Time × RM | 0.752 | 0.132 [−1.41, 1.67] | 0.868 |

| Time × TPTD | 0.086 | −0.672 [−2.24, 0.90] | 0.406 |

| Covariates | | | |

| Time × Initial VCR d | - | −0.033 [−0.05, −0.01] | 0.003 * |

3.2. Effect of Medication on Vertebral Compression Rate and Bone Mineral Density

Analysis of the overall VCR change from baseline to 3 months revealed no statistically significant difference among the four groups (One-way ANOVA, p = 0.3898). The mean (±SD) change was 24.90 ± 17.46 for the RM group, 21.87 ± 16.34 for the TPTD group, 19.81 ± 18.86 for the DMAB group, and 27.08 ± 17.26 for the control group.

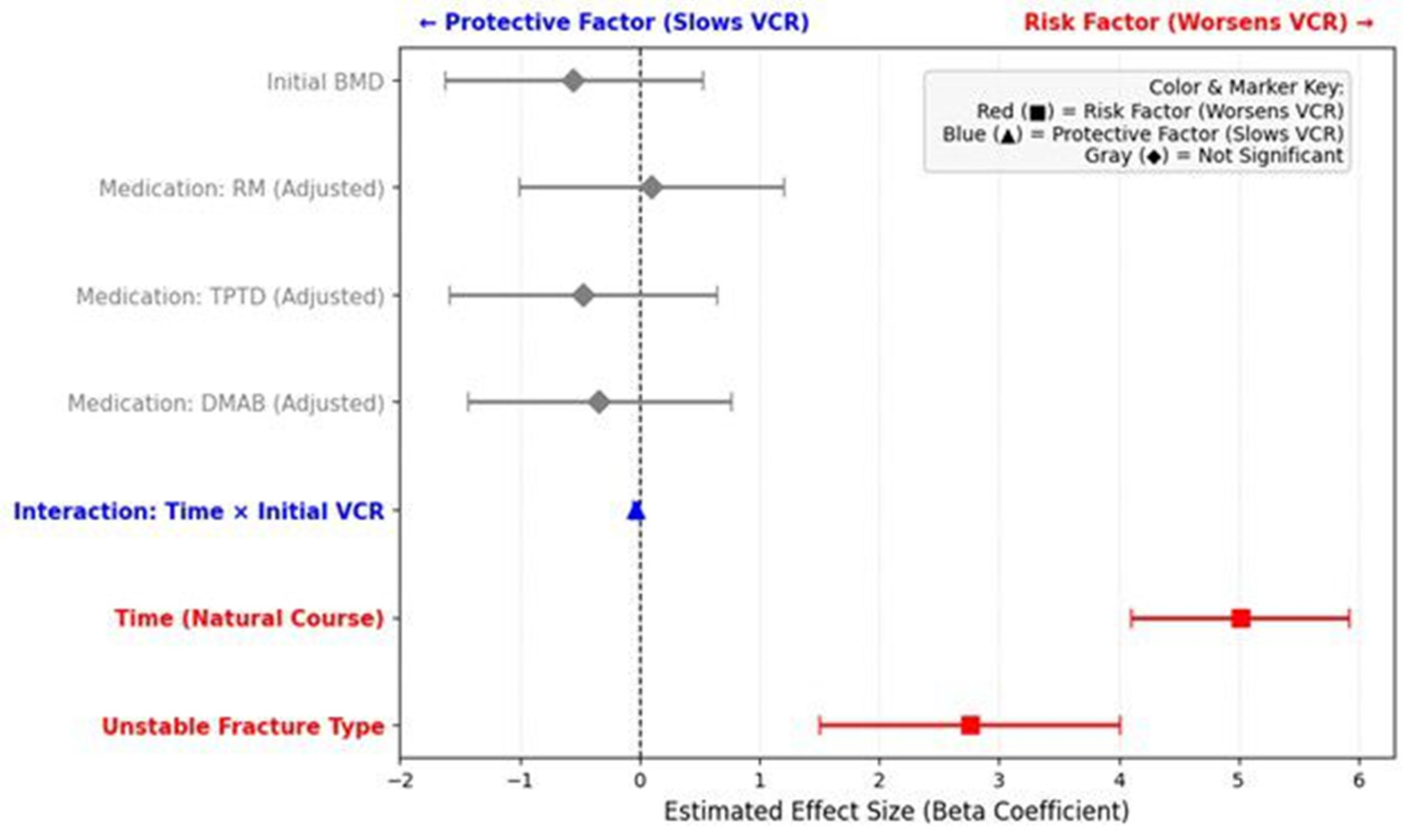

In the unadjusted LMM analysis, a statistically significant time-by-medication interaction effect was initially observed for the DMAB group compared to the Control group (β = −1.331; 95% CI: −2.34 to −0.32; p = 0.010), suggesting a slower progression of compression in the DMAB group.

As shown in

Table 1, the DMAB group had a significantly higher initial VCR (25.14 ± 14.28%) compared to other groups (

p = 0.003), indicating a potential selection bias. To account for this baseline imbalance, an adjusted LMM analysis was performed by treating the initial VCR as a covariate. After adjusting for this factor, the previously observed protective effect of DMAB was no longer statistically significant (β = −0.339; 95% CI: −1.43 to 0.75;

p = 0.544), and no medication group showed a significant structural benefit compared to the Control group. Instead, the interaction between time and initial VCR was highly significant (β = −0.033; 95% CI: −0.05 to −0.01;

p = 0.003), confirming that the initial severity of compression, rather than the medication type, was the primary driver of the VCR trajectory.

In the analysis of bone density, the 1-year change in spine BMD T-score also showed no statistically significant difference among the groups (One-way ANOVA, p = 0.5478). The mean (±SD) T-score change was 0.56 ± 0.62 for the RM group, 0.58 ± 0.44 for the TPTD group, 0.50 ± 0.54 for the DMAB group, and 0.14 ± 0.59 for the control group.

In summary, while the unadjusted analysis indicated a significant difference in VCR progression for the DMAB group, this significance was no longer observed after adjusting for the initial VCR. In the final adjusted model, only the interaction between time and initial VCR remained statistically significant (p = 0.003), whereas the interaction between time and medication did not. Similarly, no significant difference was observed in the 1-year change in spine BMD among the medication groups.

The calculated Cohen’s d effect sizes for the 3-month VCR change compared to the control group were 0.12 for the RM group, 0.31 for the TPTD group, and 0.40 for the DMAB group. Despite these trends, none of the medication groups reached the defined MCID threshold of 10% after covariate adjustment, further supporting the limited structural impact of pharmacological intervention during the acute phase.

In summary, our adjusted LMM identifies a significant ‘floor effect’ in vertebral progression (β = −0.033, 95% CI: −0.05 to −0.01, p = 0.003). This concept suggests that vertebrae with a higher initial compression rate have a naturally lower potential for additional height loss, as the trabecular bone is already significantly compacted. Conversely, fractures with low initial VCR are at the highest risk for precipitous collapse, emphasizing that the initial degree of severity—rather than the pharmacological regimen—is the primary determinant of the 3-month structural trajectory.

3.3. Effect of Fracture Type on Vertebral Compression Rate

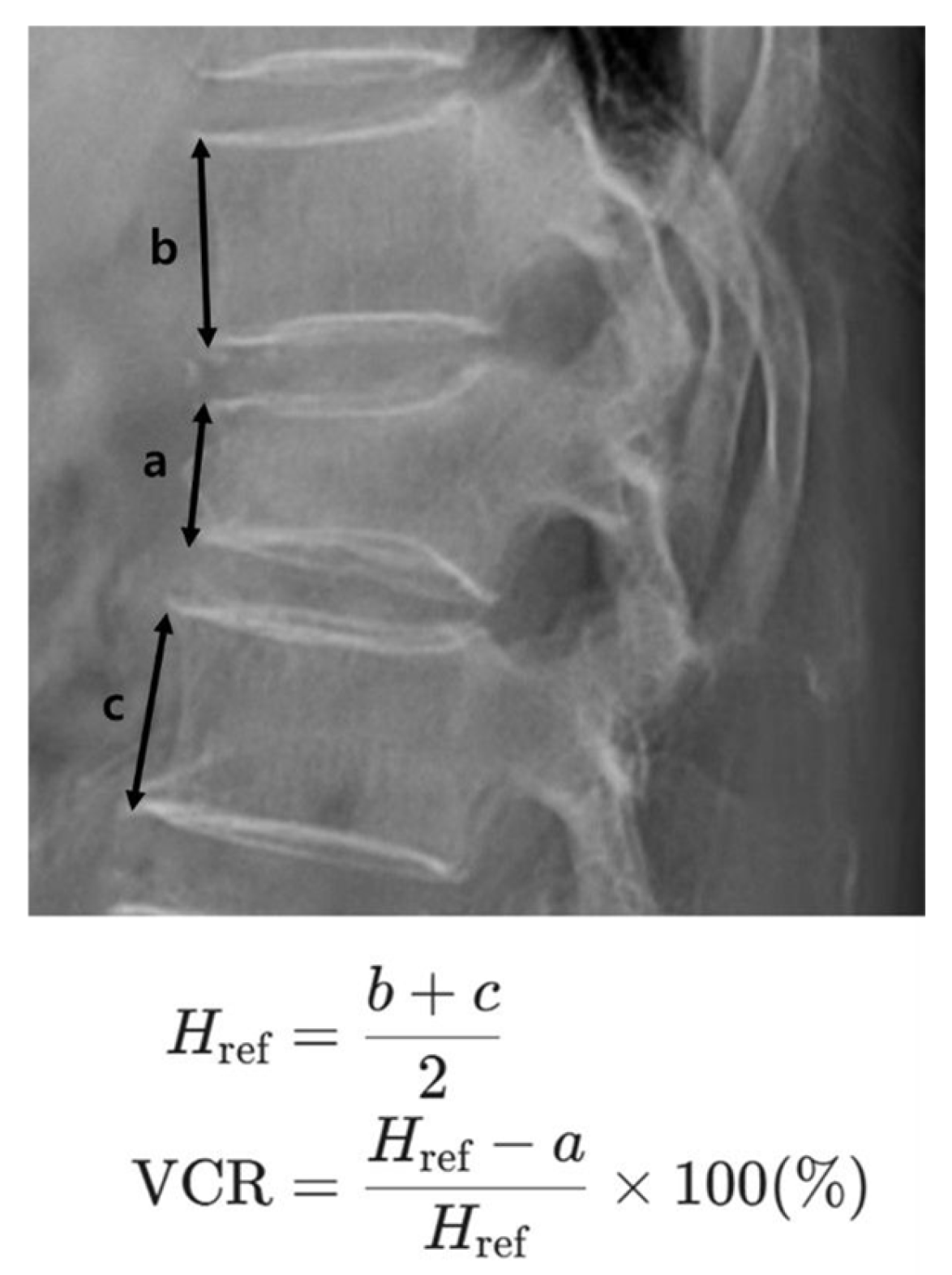

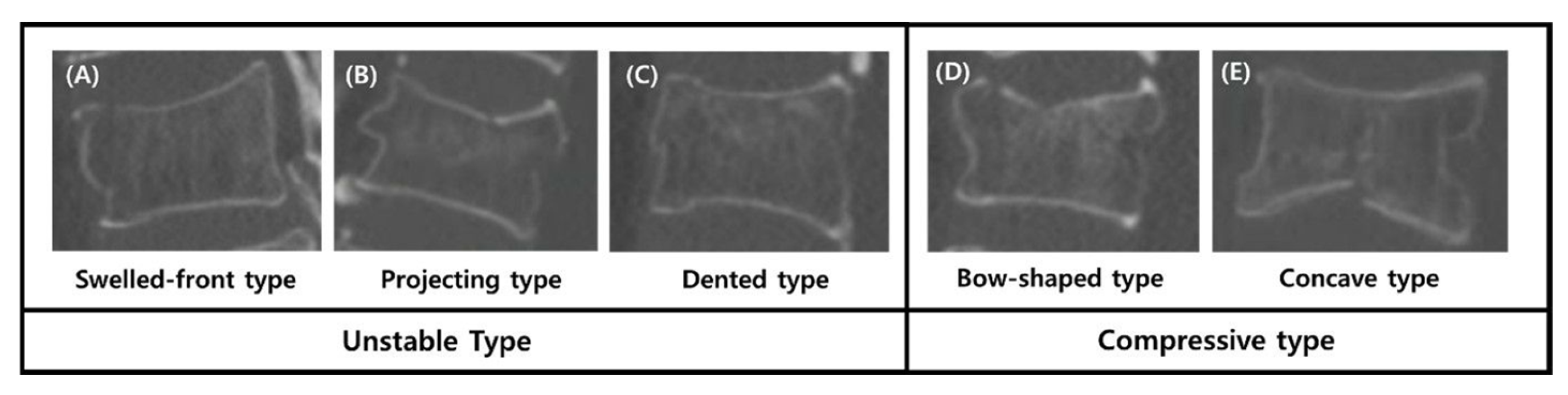

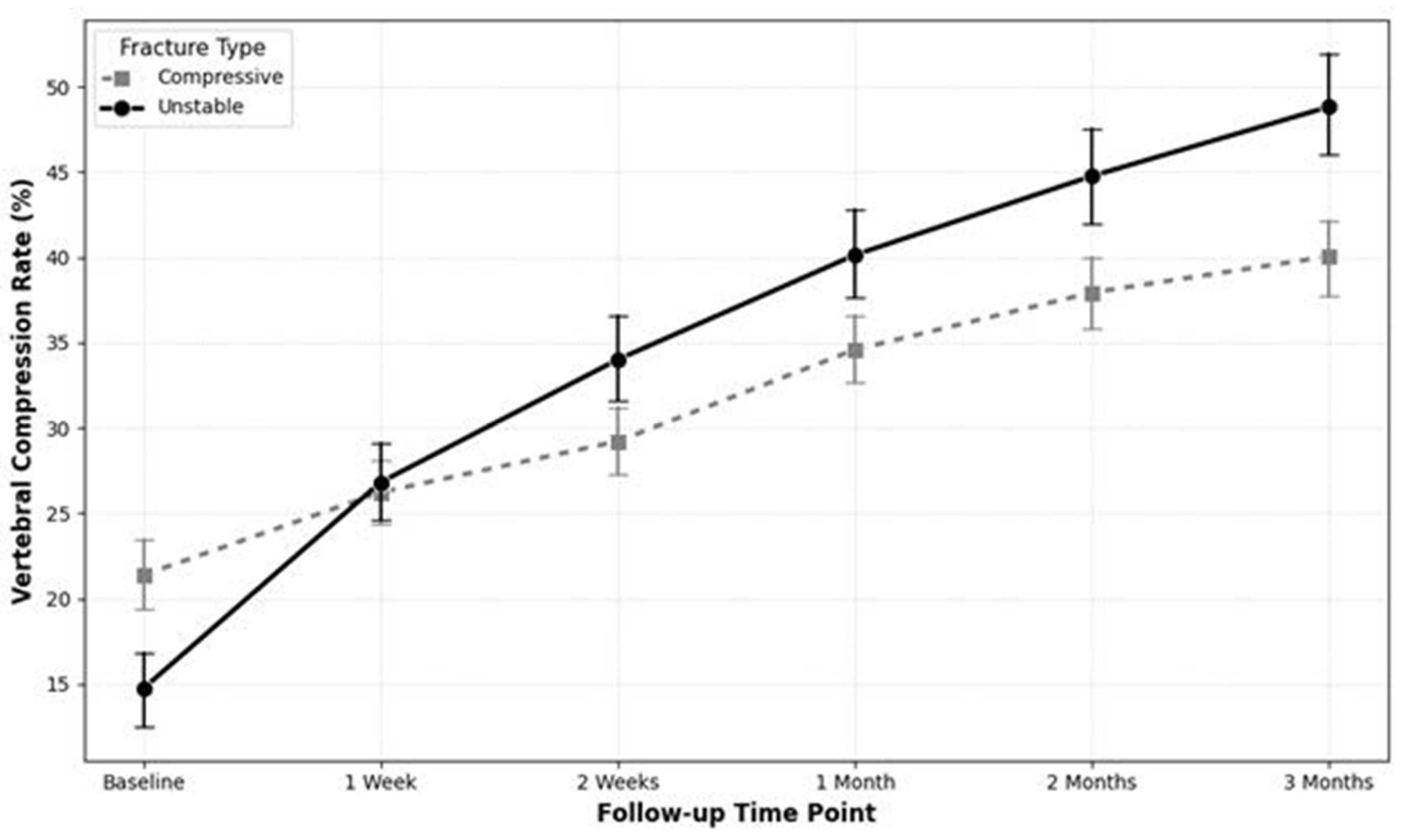

To evaluate the impact of fracture morphology on VCR progression independently of medication, the cohort was stratified into the Unstable type (n = 36) and the Compressive type (n = 87) based on the Sugita classification.

An independent t-test revealed that the Unstable group experienced a significantly greater increase in the VCR during the first two weeks of follow-up. The mean increase in VCR for the Unstable group was significantly higher during both the interval between baseline and the one-week follow-up (12.06 ± 14.55 vs. 4.83 ± 7.46; p = 0.0004) and the interval between the one-week and two-week follow-ups (7.19 ± 6.30 vs. 2.99 ± 5.83; p = 0.0006). Notably, the Unstable group experienced an additional cumulative height loss of 11.43% compared to the Compressive group within the first 14 days, representing a substantial clinical disparity in acute structural failure.

An LMM analysis assessing the entire 3-month trajectory confirmed this finding. A significant time-by-group interaction effect was observed (β = 2.758; 95% CI: 1.51 to 4.01;

p < 0.0001), indicating that the Unstable group had a statistically significant and more rapid progression of vertebral compression over time compared to the Compressive group (

Figure 4).

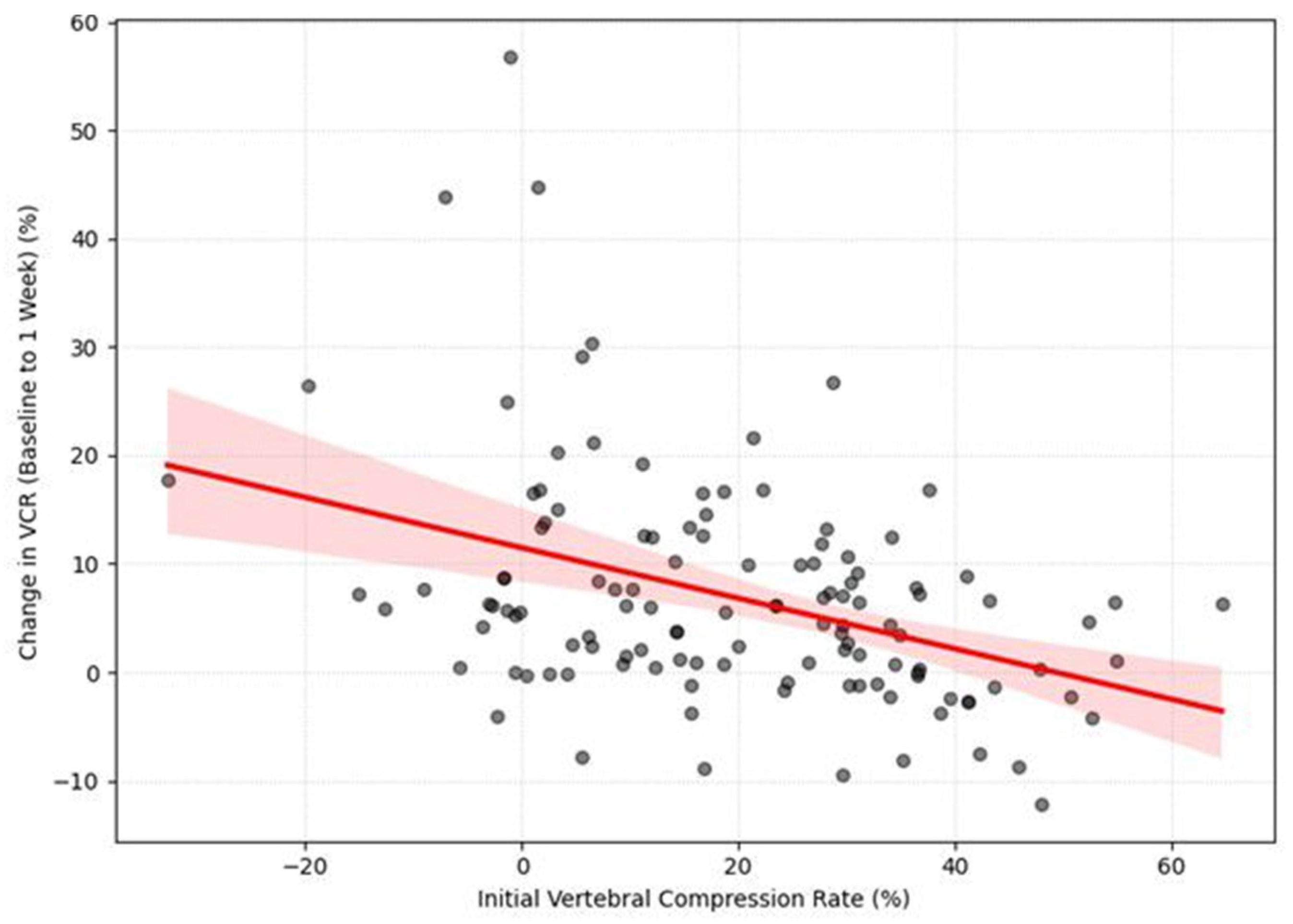

3.4. Relationship Between Initial and Subsequent Changes in Compression Rate

Next, we examined the relationship between the initial VCR and its subsequent progression. A Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between the initial vertebral compression rate (VCR) and the subsequent change in VCR (ΔVCR) during the first week of follow-up (r = −0.395,

p < 0.001). (

Figure 5) This indicates that a higher initial compression rate was associated with a smaller amount of subsequent compression change. The negative correlation was still significant from week 1 to week 2, although it was weaker (r = −0.189,

p = 0.037). After two weeks, no significant correlations were found (

p > 0.05).

The LMM analysis further clarified these temporal dynamics. There was a significant negative effect of time on the ΔVCR (β = −1.911, p < 0.001), indicating that the vertebra compressed the most during the first few weeks, and then the rate of further compression slowed down. Furthermore, the LMM revealed a significant negative main effect of the initial VCR on the overall change in compression (β = −0.178, p < 0.001).

Finally, the LMM revealed a significant interaction effect between time and the initial VCR (β = 0.052, p < 0.001). This finding indicates that the rate of compression change over time was different for patients with high versus low initial compression rates. Specifically, patients with a low initial VCR experienced a rapid progression of compression in the early stages, which then decelerated over time. In contrast, patients who presented with a high initial VCR from the outset showed a more gradual and steady pattern of compression change.

3.5. Relationship Between Initial Bone Mineral Density and Change in Compression Rate

The influence of initial bone mineral density (BMD) on VCR change was also assessed. A Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to assess the direct linear relationship between initial spine bone mineral density (BMD) and the subsequent change in the vertebral compression rate (VCR). No significant correlation was observed between these two variables. Specifically, the correlation between initial BMD and the change in VCR from baseline to 1 week (r = −0.129, p = 0.155) and from 1 week to 2 weeks (r = 0.038, p = 0.678) were both non-significant.

To further evaluate the influence of initial BMD on the VCR over the entire follow-up period, an LMM analysis was performed. The results of the LMM analysis showed that there was no significant main effect of initial BMD on the change in VCR (β = −0.551, p = 0.316). Furthermore, the interaction effect between initial BMD and time was also not statistically significant (β = 0.238, p = 0.279).

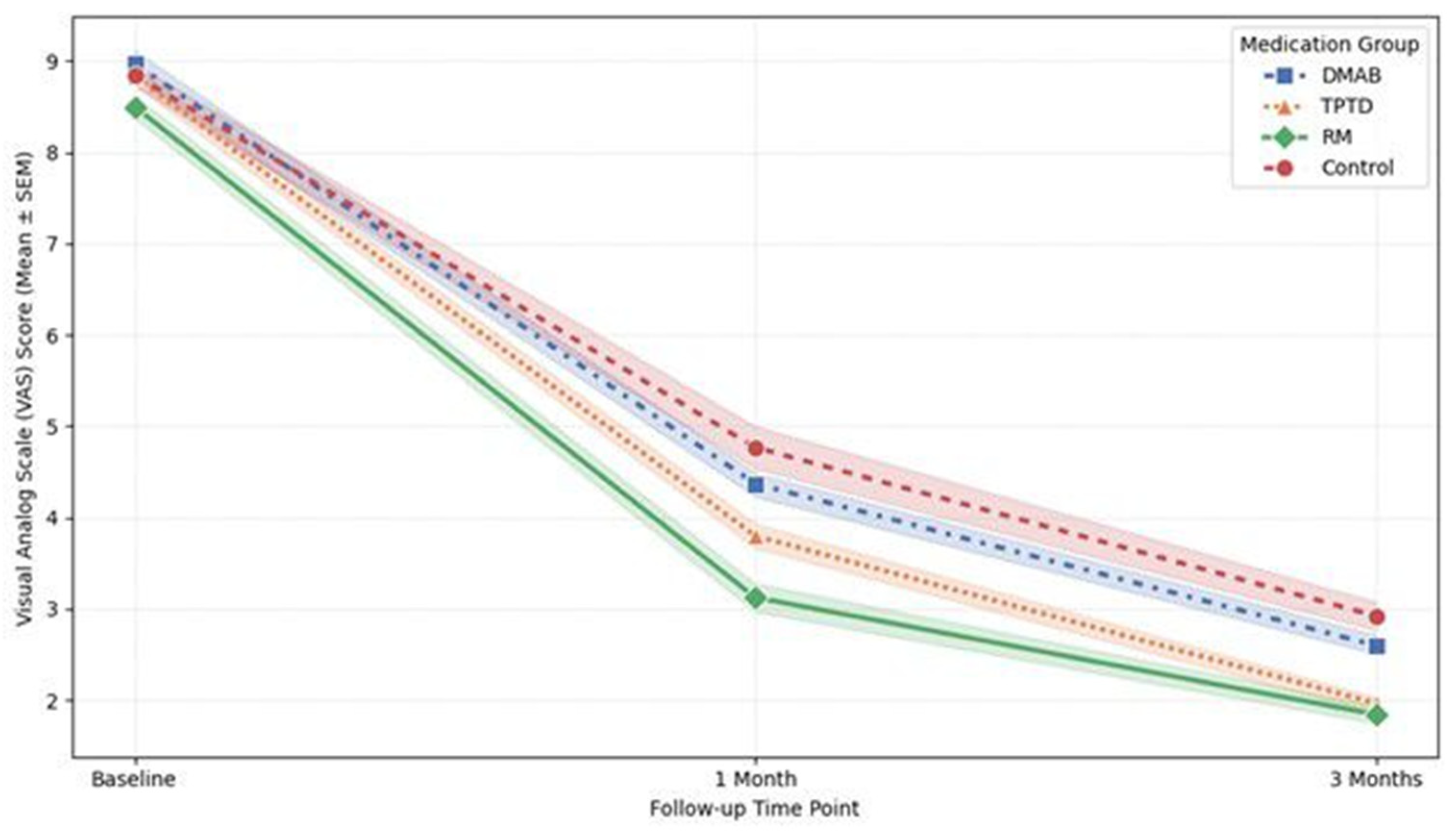

3.6. Clinical Outcomes: VAS Scores for Back Pain

All treatment groups demonstrated significant pain relief over the 3-month follow-up period (ANOVA, p = 0.002). In terms of the absolute reduction in VAS scores from baseline to 3 months, the TPTD group showed the largest mean reduction (6.87 ± 0.78), followed closely by the RM group (6.66 ± 0.97).

However, the LMM analysis, which evaluates the overall pain trajectory throughout the treatment period, revealed that the RM group was the only group to show a statistically significant difference compared to the Control group (Coef. = −0.797,

p = 0.014). This indicates that patients treated with RM experienced significantly lower overall pain levels during the follow-up period compared to those in the Control group. In contrast, neither the TPTD (

p = 0.137) nor the DMAB (

p = 0.482) group showed a statistically significant difference in pain trajectory compared to the Control group (

Figure 6).

Additionally, a positive correlation was observed between the initial VCR and the reduction in VAS score (r = 0.307, p < 0.001), indicating that patients with more severe initial compression experienced a greater magnitude of pain relief. No significant difference in pain reduction was found based on fracture morphology (p = 0.434).

The line graph illustrates the changes in mean VAS scores at baseline, 1 month, and 3 months for each treatment group. While all groups exhibited a reduction in pain over time, the linear mixed model (LMM) analysis revealed that the Romosozumab (RM) group (solid line with diamond markers) maintained significantly lower overall pain levels throughout the follow-up period compared to the Control group (dashed line with circle markers) (p = 0.014). In contrast, the Denosumab (DMAB) and Teriparatide (TPTD) groups did not show a statistically significant difference in pain trajectory compared to the Control group. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM).

3.7. Incidence of IVC Formation

At the 3-month follow-up, radiological evidence of potential osteonecrosis, indicated by the presence of an IVC, was identified in 8 out of 123 patients (6.5%). The incidence of IVC formation did not differ significantly among the medication groups (

p = 0.489). However, a significant association was found between fracture morphology and the development of an IVC. Patients with Unstable type fractures had a significantly higher incidence of IVC formation compared to those with Compressive type fractures (5/36 [13.9%] vs. 3/87 [3.4%], Fisher’s exact test,

p = 0.047). No significant difference was observed in the initial VCR between patients who developed an IVC and those who did not (16.14% vs. 19.68%,

p = 0.591). To summarize the overall impact of the investigated factors on vertebral compression progression, the estimated effect sizes (Beta coefficients) for medication, fracture type, and initial severity are visually synthesized in a forest plot (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the factors influencing the progression of vertebral compression during the critical first three months following an OVCF [

16]. Specifically, we first evaluated the impact of different pharmacological interventions—including anabolic agents and antiresorptives—and subsequently analyzed the influence of baseline prognostic factors such as fracture morphology and initial severity. Our analysis demonstrated that the type of anti-osteoporotic medication did not significantly mitigate the radiographic progression of vertebral collapse during this acute period. Instead, the morphological type of the fracture and the initial severity of compression were identified as the primary determinants influencing further vertebral compression.

Several previous studies have suggested that anabolic agents, such as TPTD and RM, can accelerate fracture healing and prevent progressive collapse in OVCFs. [

17,

18] For instance, a randomized controlled trial by Aspenberg et al. demonstrated that TPTD improved radiographic fracture healing compared to placebo [

19]. Similarly, RM has been shown to rapidly increase bone mineral density and reduce fracture risk [

20]. Based on these findings, it was hypothesized that early administration of anabolic agents would mitigate vertebral height loss in the acute phase. However, contrary to these expectations, our study found that the type of medication did not significantly alter the structural trajectory of vertebral collapse over the 3-month follow-up. This discrepancy may be attributed to the duration of treatment. Most studies demonstrating the structural benefits of anabolic agents involved treatment periods of at least 6 to 12 months [

21]. In the acute phase (first 3 months), the biological process of callus formation and mineralization may not be sufficient to counteract the mechanical forces causing collapse, regardless of the potent anabolic stimulus. This suggests that while anabolic agents are effective for long-term bone quality, their ability to mechanically stabilize an acute fracture within a short timeframe may be limited.

While pivotal long-term studies, such as the ARCH and FRAME trials, have established the superior efficacy of anabolic agents in increasing bone mineral density (BMD) and reducing fracture risk over 12 to 24 months, our findings highlight a critical temporal disconnect in the acute phase [

9,

20]. The biological onset of increased bone formation and subsequent mineralization typically requires several months to translate into enhanced structural stiffness [

21,

22]. In contrast, the mechanical failure of a fractured vertebra occurs most precipitously within the first few weeks post-injury, driven by immediate weight-bearing forces [

10,

16]. Therefore, even the most potent anabolic stimulus may be insufficient to counteract this early ‘mechanical window’ of instability before significant callus formation can manifest [

22].

A pivotal finding of this study is that the apparent protective effect of medication observed in the initial analysis was attributable to baseline variances rather than pharmacological efficacy. To overcome the limitations of simple cross-sectional comparisons and accurately track the longitudinal trajectory of vertebral collapse, we employed an LMM analysis. In our unadjusted LMM, DMAB initially appeared to slow the progression of vertebral collapse. However, after adjusting for the initial vertebral compression rate (VCR) within the LMM framework, this protective effect disappeared. The DMAB group had a significantly higher initial VCR, suggesting that the observed stability was likely due to a ‘floor effect’—where severe fractures have less trabecular bone remaining to collapse further—rather than a direct benefit of the drug. This finding underscores the limitations of short-term (3-month) pharmacological intervention in altering the structural course of acute fractures. Several studies have demonstrated that anabolic agents, such as TPTD and RM, require a longer duration (typically 6 to 12 months) to stimulate sufficient callus formation and mineralization to counteract mechanical loading [

22]. Therefore, in the acute phase, the biological process of bone formation may not be rapid enough to prevent mechanical collapse caused by weight-bearing forces.

The observed clinical dissociation between pain relief and the absence of structural protection in the RM group may suggest a need for further mechanistic exploration. One possible explanation is that RM’s unique dual action—simultaneously promoting bone formation and inhibiting resorption might influence local bone turnover dynamics. It is conceivable that such biological effects could potentially reduce micromotion at the fracture site even before macroscopic structural stability is fully realized, thereby possibly contributing to symptomatic relief despite the radiographic progression of the fracture.

The apparent discrepancy between our findings and previous studies can be explained through a temporal analysis of fracture healing. While these earlier reports highlighted the biological potential of anabolic agents in enhancing stability, our results reflect a critical temporal mismatch between pharmacological onset and the rapid mechanical failure observed in the acute phase [

13,

19]. In our cohort, despite the prompt initiation of medication upon diagnosis, the most significant progression of collapse occurred within the first two weeks. This suggests that the rate of mechanical collapse outpaces the time required for pharmacological agents to achieve sufficient bone mineralization and structural stiffness. Ultimately, this underscores that during the acute ‘mechanical window’ of instability, initial fracture characteristics are more decisive factors for height loss than the biological stimulus provided by early medication.

Although the medications did not differ significantly in preventing structural collapse, significant differences were observed in clinical outcomes regarding pain relief. Specifically, the RM group demonstrated a distinct advantage in pain management, maintaining significantly lower pain scores throughout the follow-up period compared to the control group in the LMM analysis. While the precise mechanism remains unclear within the scope of this study, this finding might be related to the unique dual action of RM, which simultaneously promotes bone formation and inhibits resorption [

20]. Previous literature suggests that such anabolic effects could potentially contribute to the earlier stabilization of micro-fractures within the vertebral body [

23]. In this context, our observation implies that RM could be a favorable option for improving the patient’s quality of life through effective pain relief in the acute phase, even if structural progression is not fully prevented. This biological potential is further supported by recent preclinical evidence demonstrating that romosozumab significantly enhances spinal implant stability and osseointegration in osteoporotic bone models [

24].

Our findings strongly support the prognostic value of the Sugita classification, first proposed to predict the risk of delayed union and collapse [

10]. Consistent with Sugita et al.’s original observations, we identified the ‘Unstable type’ (swelled, projecting, and dented) as a major risk factor for rapid vertebral collapse. While previous studies have demonstrated that TPTD can accelerate fracture healing and promote union in osteoporotic vertebral fractures [

13], our data indicates that the mechanical instability of these fracture types often outweighs the biological effects of medication in the acute phase. The precipitous collapse observed in the Unstable group within the first two weeks underscores that pharmacological treatment alone is insufficient for these high-risk morphotypes. Therefore, for patients presenting with ‘Unstable’ morphology, clinicians should consider more aggressive closed management strategies, including stricter immobilization and closer radiographic monitoring, to promptly identify progressive collapse and prevent severe deformity, regardless of the prescribed osteoporosis medication.

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, the retrospective design and the requirement for a minimum one-year follow-up likely introduced selection bias. Specifically, this inclusion criterion may have introduced a survivorship bias, as it potentially excluded the most severe or complicated cases—such as patients who might have undergone early surgical intervention, experienced mortality, or been lost to follow-up due to poor clinical status. While we cannot account for these missing data points due to the retrospective nature of this study, this exclusion could have attenuated the observed differences between treatment groups. Additionally, the significantly higher initial VCR in the DMAB group reflects real-world clinical practices where socioeconomic factors, such as insurance coverage and patient preference, heavily influenced treatment allocation rather than randomization. While we utilized adjusted linear mixed models (LMMs) to control these baseline imbalances, the possibility of residual confounding remains.

Second, although our intra-observer reliability was excellent (ICC: 0.96), all radiographic assessments were performed by a single observer. Furthermore, the exclusive use of supine radiographs represents a significant limitation of this study. This imaging protocol was initially prioritized to ensure patient safety and prevent potential fracture aggravation during the acute phase, where severe pain often precluded weight-bearing standing views. To maintain methodological consistency and ensure uniformity across the serial 3-month follow-up, supine measurements were utilized throughout the study period. However, we fully acknowledge that this static assessment may fail to capture dynamic instability, potentially resulting in an underestimation of the true extent of vertebral collapse compared to weight-bearing radiographs.

Third, the relatively small sample sizes for specific fracture morphology subtypes—such as the Swelled (n = 9) and Dented (n = 8) types—necessitated their dichotomization into broader ‘unstable’ and ‘compressive’ categories. While this categorization was biomechanically justified based on prognostic implications for instability, it inherently reduced the statistical power to detect more nuanced, subtype-specific interactions between pharmacological efficacy and individual fracture morphologies.

Fourth, the 3-month observation window for vertebral height loss and 1-year follow-up for BMD may be relatively short. This highlights a fundamental distinction between the acute biomechanical collapse phase—which occurs rapidly over days and weeks—and the biological bone remodeling phase, which requires several months to years to achieve structural rigidity. Therefore, our null structural results should be interpreted as a limited effect on acute mechanical failure rather than an indicator of long-term pharmacological inefficacy for osteoporosis treatment.

Fifth, medication adherence was verified through prescription records rather than objective measures such as injection logs. While this reflects the pragmatic reality of a retrospective study, potential variations in individual compliance within the initial window remain an inherent limitation. Additionally, the absence of functional outcome metrics, such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), limits our ability to correlate radiographic changes with clinical disability.

Lastly, this was a single-center study with a limited sample size, and our results demonstrate associations rather than definitive causal links regarding medication efficacy. The identification of IVC formation was also based on an operational definition due to the short timeframe. Future large-scale prospective studies are warranted to validate these findings.