Diagnostic and Severity Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease Using ApoB/ApoA-I Ratio: Insights from a Statin-Treated Eastern European Cohort

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Patient Enrollment, and Investigations

2.2. Statistical Analysis

2.3. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. ApoB/ApoA Ratio-Based Analysis

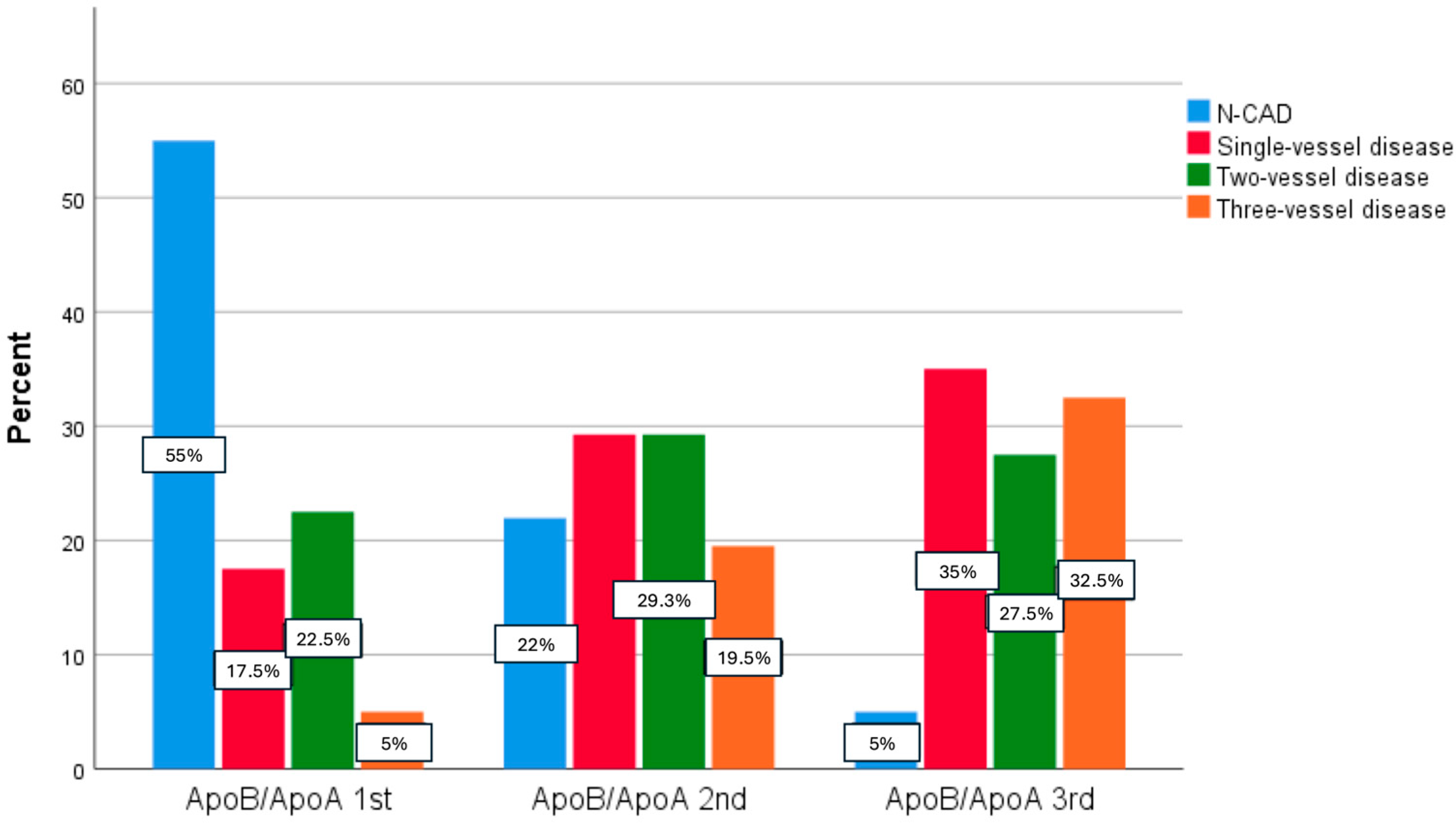

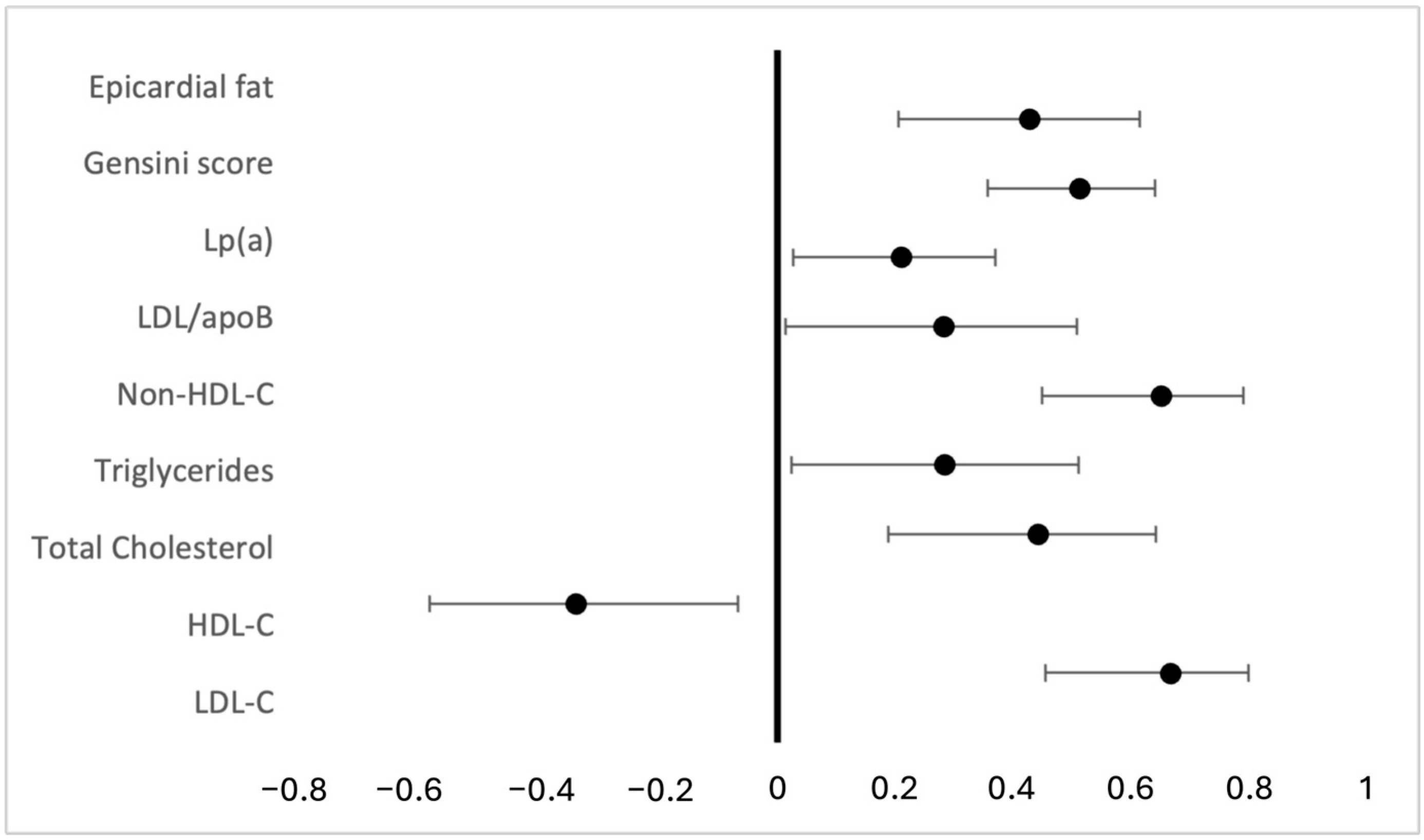

3.3. Association Between apoB/apoA Ratio and the Severity of CAD

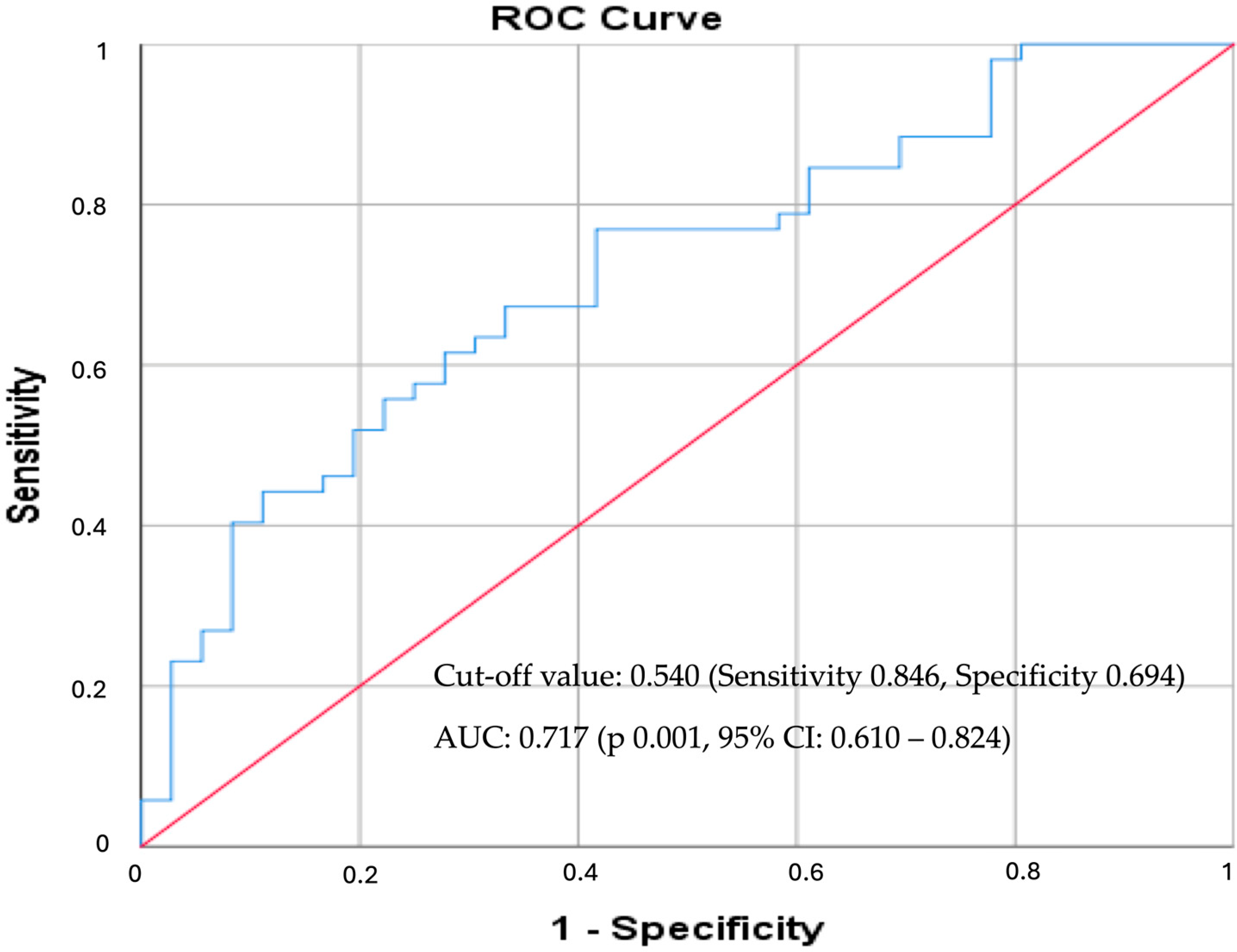

3.4. ApoB/ApoA Ratio as a Predictor for CAD

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2023 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global burden of 292 causes of death in 204 countries and territories and 660 subnational locations, 1990–2023: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2023. Lancet 2025, 406, 1811–1872. [CrossRef]

- Jigoranu, R.A.; Roca, M.; Costache, A.D.; Mitu, O.; Oancea, A.F.; Miftode, R.S.; Haba, M.Ș.C.; Botnariu, E.G.; Maștaleru, A.; Gavril, R.S.; et al. Novel Biomarkers for Atherosclerotic Disease: Advances in Cardiovascular Risk Assessment. Life 2023, 13, 1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, M.A.; Mitchell, R.N.; Stone, J.R. Pathophysiology of Atherosclerosis. In Cellular and Molecular Pathobiology of Cardiovascular Disease; Willis, M.S., Homeister, J.W., Stone, J.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mach, F.; Koskinas, K.C.; Lennep, J.E.R.v.; Tokgözoğlu, L.; Badimon, L.; Baigent, C.; Benn, M.; Binder, C.J.; Catapano, A.L.; De Backer, G.G.; et al. 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 4359–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniderman, A.D. ApoB vs non-HDL-C vs LDL-C as Markers of Cardiovascular Disease. Clin. Chem. 2021, 67, 1440–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glavinovic, T.; Thanassoulis, G.; de Graaf, J.; Couture, P.; Hegele, R.A.; Sniderman, A.D. Physiological Bases for the Superiority of Apolipoprotein B over Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol as a Marker of Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morze, J.; Melloni, G.E.M.; Wittenbecher, C.; Ala-Korpela, M.; Rynkiewicz, A.; Guasch-Ferré, M.; Ruff, C.T.; Hu, F.B.; Sabatine, M.S.; Marston, N.A. ApoB-containing lipoproteins: Count, type, size, and risk of coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2691–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, S.; Pan, H.; Yang, S.; Cheng, W. Relationship between serum apolipoprotein B and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in individuals with hypertension: A prospective cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2024, 24, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayturan, O.; Kapadia, S.; Nicholls, S.J.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Shao, M.; Uno, K.; Shreevatsa, A.; Lavoie, A.J.; Wolski, K.; Schoenhagen, P.; et al. Clinical predictors of plaque progression despite very low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 55, 2736–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johannesen, C.D.L.; Mortensen, M.B.; Langsted, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. ApoB and Non-HDL Cholesterol Versus LDL Cholesterol for Ischemic Stroke Risk. Ann. Neurol. 2022, 92, 379–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeali, S.; Farmer, J. High-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis: The role of antioxidant activity. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2012, 14, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Han, G.; Liu, X.; Chen, B.; Peng, K.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Cui, J.; Song, L.; et al. Association of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in a Chinese population of 3.3 million adults: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2024, 42, 100874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhale, A.S.; Venkataraman, K. Leveraging knowledge of HDLs major protein ApoA1: Structure, function, mutations, and potential therapeutics. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 154, 113634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamarche, B.; Moorjani, S.; Lupien, P.J.; Cantin, B.; Bernard, P.M.; Dagenais, G.R.; Després, J.-P. Apolipoprotein A-I and B Levels and the Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease during a Five-Year Follow-Up of Men in the Québec Cardiovascular Study. Circulation 1996, 94, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haji Aghajani, M.; Madani Neishaboori, A.; Ahmadzadeh, K.; Toloui, A.; Yousefifard, M. The association between apolipoprotein A-1 plasma level and premature coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021, 75, e14578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, M.S.; Zanolla, L.; Righetti, G.; Marchetti, C.; Mocarelli, P.; Marcovina, S.M. Plasma Apolipoproteins A-I and B in Survivors of Myocardial Infarction and in a Control Group. Clin. Chem. 1998, 44, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luc, G.; Bard, J.M.; Ferrières, J.; Evans, A.; Amouyel, P.; Arveiler, D.; Fruchart, J.C.; Ducimetière, P. Value of HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein A-I, lipoprotein A-I, and lipoprotein A-I/A-II in prediction of coronary heart disease: The PRIME Study. Prospective Epidemiological Study of Myocardial Infarction. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, S.; Boden, W.E.; Hartigan, P.M.; Teo, K.K.; Maron, D.J.; Sedlis, S.P.; Kostuk, W.; Spertus, J.A.; Dada, M.; Chaitman, B.R.; et al. Low Levels of High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol and Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Stable Ischemic Heart Disease Patients: A Post-Hoc Analysis from the COURAGE Trial (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1826–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, M.J.; Hawken, S.; Wang, X.; Ounpuu, S.; Sniderman, A.; Probstfield, J.; Steyn, K.; Sanderson, J.E.; Hasani, M.; Volkova, E.; et al. Lipids, lipoproteins, and apolipoproteins as risk markers of myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): A case-control study. Lancet 2008, 372, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walldius, G.; de Faire, U.; Alfredsson, L.; Leander, K.; Westerholm, P.; Malmström, H.; Ivert, T.; Hammar, N. Long-term risk of a major cardiovascular event by apoB, apoA-1, and the apoB/apoA-1 ratio—Experience from the Swedish AMORIS cohort: A cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhu, B.; Liu, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Li, H.; Gao, C. Association between apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio and quantities of tissue prolapse on optical coherence tomography examination in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 40, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, R.I.; El-Leboudy, M.H.; El-Deeb, H.M. The Relation between ApoB/ApoA-1 Ratio and the Severity of Coronary Artery Disease in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Egypt. Heart J. 2021, 73, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aherrahrou, R.; Guo, L.; Nagraj, V.P.; Aguhob, A.; Hinkle, J.; Chen, L.; Soh, J.Y.; Lue, D.; Alencar, G.F.; Boltjes, A.; et al. Genetic regulation of atherosclerosis-relevant phenotypes in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 1552–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barre, D.E. Apoprotein(a) antagonizes the GPIIb/IIIa receptor on collagen- and ADP-stimulated human platelets. Front. Biosci. 2004, 9, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Boerwinkle, E.; Leffert, C.C.; Lin, J.; Lackner, C.; Chiesa, G.; Hobbs, H.H. Apolipoprotein(a) gene accounts for greater than 90% of the variation in plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations. J. Clin. Investig. 1992, 90, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khera, A.V.; Everett, B.M.; Caulfield, M.P.; Hantash, F.M.; Wohlgemuth, J.; Ridker, P.M.; Mora, S. Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, rosuvastatin therapy, and residual vascular risk: An analysis from the JUPITER trial (Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: An Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin). Circulation 2014, 129, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestel, P.J.; Barnes, E.H.; Tonkin, A.M.; Simes, J.; Fournier, M.; White, H.D.; Colquhoun, D.M.; Blankenberg, S.; Sullivan, D.R. Plasma lipoprotein(a) concentration predicts future coronary and cardiovascular events in patients with stable coronary heart disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 2902–2908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, J.J.; Slee, A.; O’Brien, K.D.; Robinson, J.G.; Kashyap, M.L.; Kwiterovich, P.O., Jr.; Xu, P.; Marcovina, S.M. Relationship of apolipoproteins A-I and B, and lipoprotein(a), to cardiovascular outcomes: The AIM-HIGH trial (Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with Low HDL/High Triglyceride and Impact on Global Health Outcomes). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013, 62, 1575–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Wang, M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ng, K.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V. Lp(a) [Lipoprotein(a)] concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, Y.; Minami, Y.; Kato, A.; Katsura, A.; Sato, T.; Kakizaki, R.; Nemoto, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Meguro, K.; et al. Lipoprotein (a) level is associated with plaque vulnerability in patients with coronary artery disease: An optical coherence tomography study. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2019, 24, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Yin, D.; Zhu, C.; Song, W.; Wang, H.; Jia, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Cai, Z.; Feng, L.; et al. How Do Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations Affect Clinical Outcomes for Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease Who Underwent Different Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e023578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jigoranu, R.-A.; Mitu, O.; Costache, A.-D.; Oancea, A.; Miftode, R.-S.; Buburuz, A.M.; Bazyani, A.; Simion, P.; Gavril, R.S.; Cianga, P.; et al. Moving Beyond LDL-C and Non-HDL-C: Apolipoprotein B as the Stronger Lipid-Related Predictor of Coronary Artery Disease in Statin-Treated Patients. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gensini, G.G. A More Meaningful Scoring System for Determining the Severity of Coronary Heart Disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 1983, 51, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Cantor, A.; Dana, T.; Wagner, J.; Ahmed, A.Y.; Fu, R.; Ferencik, M. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2022, 328, 754–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criqui, M.H.; Aboyans, V.; Allison, M.A.; Denenberg, J.O.; Forbang, N.; McDermott, M.M.; Wassel, C.L.; Wong, N.D. Peripheral Artery Disease and Aortic Disease. Glob. Heart 2016, 11, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Kuronuma, K.; Rozanski, A.; Budoff, M.J.; Miedema, M.D.; Nasir, K.; Shaw, L.J.; Rumberger, J.; Gransar, H.; Blumenthal, R.S.; et al. Implication of Thoracic Aortic Calcification over Coronary Artery Calcification for Predicting and Reclassifying ASCVD Mortality Risk. Am. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 7, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welsh, C.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Brown, R.; Mackay, D.F.; Lewsey, J.; Mark, P.B.; Gray, S.R.; Ferguson, L.D.; Anderson, J.J.; Lyall, D.M.; et al. Comparison of Conventional Lipoprotein Tests and Apolipoproteins in the Prediction of Cardiovascular Disease. Circulation 2019, 140, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florvall, G.; Basu, S.; Larsson, A. Apolipoprotein A1 Is a Stronger Prognostic Marker than HDL and LDL Cholesterol for Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Elderly Men. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006, 61, 1262–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soffer, D.E.; Marston, N.A.; Maki, K.C.; Jacobson, T.A.; Bittner, V.A.; Peña, J.M.; Thanassoulis, G.; Martin, S.S.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Virani, S.S.; et al. Role of Apolipoprotein B in the Clinical Management of Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: An Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, e647–e663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, R.; Li, Y.; Li, W.; Wei, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Zhou, J. Apolipoprotein B/A1 Ratio Is Associated with Severity of Coronary Artery Stenosis in CAD Patients but Not in Non-CAD Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Dis. Markers 2021, 2021, 8959019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liting, P.; Guoping, L.; Zhenyue, C. Apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A1 Ratio and Non-High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol: Predictive Value for Coronary Heart Disease Severity and Prognostic Utility in CHD Patients. Herz 2015, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddox, T.M.; Stanislawski, M.A.; Grunwald, G.K.; Bradley, S.M.; Ho, P.M.; Tsai, T.T.; Patel, M.R.; Sandhu, A.; Valle, J.; Magid, D.J.; et al. Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Risk of Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2014, 312, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, M.S.; Hulten, E.; Ghoshhajra, B.; O’Leary, D.; Christman, M.P.; Montana, P.; Truong, Q.A.; Steigner, M.; Murthy, V.L.; Rybicki, F.J.; et al. Prognostic Value of Nonobstructive and Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease Detected by Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography to Identify Cardiovascular Events. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2014, 7, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.X.; Eshtehardi, P.; Varghese, T.; Goyal, A.; Mehta, P.K.; Kang, W.; Leipsic, J.; Hartaigh, B.Ó.; Bairey Merz, C.N.; Berman, D.S.; et al. Prognostic Significance of Nonobstructive Left Main Coronary Artery Disease in Women Versus Men: Long-Term Outcomes from the CONFIRM Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, e006246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Gao, J.; Tian, X.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, P. ApoB/ApoA-I Is Associated with Major Cardiovascular Events and Readmission Risk of Patients after Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in One Year. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisinger, C.; Loewel, H.; Mraz, W.; Koenig, W. Prognostic Value of Apolipoprotein B and A-I in the Prediction of Myocardial Infarction in Middle-Aged Men and Women: Results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg Cohort Study. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sondermeijer, B.M.; Rana, J.S.; Arsenault, B.J.; Shah, P.K.; Kastelein, J.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Khaw, K.-T. Non-HDL Cholesterol vs. Apo B for Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Healthy Individuals: The EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 43, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lipoprotein(a) Concentration and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Nonvascular Mortality. JAMA 2009, 302, 412–423. [CrossRef]

- Kamstrup, P.R.; Tybjærg-Hansen, A.; Steffensen, R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Genetically Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2009, 301, 2331–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsimikas, S. A Test in Context: Lipoprotein(a)—Diagnosis, Prognosis, Controversies, and Emerging Therapies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 692–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriarty, P.M.; Gorby, L.K.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Kastelein, J.P.; Davidson, M.H.; Tsimikas, S. Lipoprotein(a) and Its Potential Association with Thrombosis and Inflammation in COVID-19: A Testable Hypothesis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2020, 22, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneva, A.M.; Potolitsyna, N.N.; Bojko, E.R.; Odland, J.Ø. The apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-I ratio as a potential marker of plasma atherogenicity. Dis. Markers 2015, 2015, 591454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contois, J.H.; Langlois, M.R.; Cobbaert, C.; Sniderman, A.D. Standardization of Apolipoprotein B, LDL-Cholesterol, and Non-HDL-Cholesterol. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2023, 12, e030405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kathiresan, S.; Otvos, J.D.; Sullivan, L.M.; Keyes, M.J.; Schaefer, E.J.; Wilson, P.W.; D’Agostino, R.B.; Vasan, R.S.; Robins, S.J. Increased small low-density lipoprotein particle number: A prominent feature of the metabolic syndrome in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2006, 113, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Overall (n = 121) | NS-CAD (n = 69) | S-CAD (n = 52) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.2 ± 9.3 | 62.94 ± 9.28 | 66 ± 9.33 | 0.076 |

| Male gender (%) | 63.6% | 59.4% | 69.2% | 0.267 |

| Smoking (%) | 56.2% | 56.6% | 55.8% | 0.934 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.17 ± 5.70 | 30.74 ± 5.93 | 29.42 ± 5.33 | 0.202 |

| AF (%) | 28.9% | 27.53% | 26.92% | 0.956 |

| DM (%) | 24.8% | 20.3% | 30.8% | 0.186 |

| CKD (%) | 21% | 20.28% | 21.15% | 0.821 |

| COPD (%) | 9.1% | 5.79% | 13.46 | 0.147 |

| Stroke/TIA (%) | 9.9% | 8.69 | 11.53% | 0.605 |

| Aortic atherosclerosis (%) | 25.6% | 25.8% | 74.2% | 0.000 |

| Glycemia (mg/dL) | 110.15 ± 29.83 | 109.7 ± 29.73 | 110.7 ± 30.25 | 0.862 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.45 ± 10.79 | 25.41 ± 13.42 | 23.40 ± 6.91 | 0.351 |

| ALT (U/L) | 24.74 ± 12.97 | 25.34 ± 14.77 | 24.06 ± 10.68 | 0.617 |

| GGT (U/L) | 49.07 ± 57.57 | 57.50 ± 69.41 | 40.16 ± 40.73 | 0.198 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.88 ± 0.29 | 0.88 ± 0.28 | 0.87 ± 0.29 | 0.766 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 86.43 ± 18.35 | 86.12 ± 19.48 | 86.86 ± 16.80 | 0.837 |

| Gensini Score | 17.6 ± 24.73 | 2.63 ± 3.74 | 37.5 ± 26.72 | 0.000 |

| Lipid parameters | ||||

| TC (mg/dL) | 165.81 ± 41.97 | 155.60 ± 33.22 | 178.86 ± 48.29 | 0.003 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 102.65 ± 38.38 | 92.76 ± 30.67 | 115.53 ± 43.63 | 0.002 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 46.82 ± 12.97 | 47.19 ± 12.22 | 46.36 ± 13.97 | 0.737 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 107.48 ± 50.23 | 103.95 ± 46.76 | 112.08 ± 54.57 | 0.396 |

| ApoB (mg/dL) | 81.6 ± 26.65 | 73 ± 23.47 | 93.01 ± 26.51 | 0.000 |

| ApoA (mg/dL) | 134.33 ± 26.56 | 138.43 ± 27.05 | 128.90 ± 25.13 | 0.048 |

| ApoB/ApoA | 0.61 ± 0.19 | 0.53 ± 0.16 | 0.73 ± 0.18 | 0.000 |

| Lp(a) (mg/dL) | 17.19 ± 22.96 | 13.03 ± 21.70 | 22.64 ± 23.64 | 0.022 |

| Variable | ApoB/ApoA 1st (0.22–0.50) | ApoB/ApoA 2nd (0.50–0.68) | ApoB/ApoA 3rd (0.68–1.11) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristics | ||||

| Age | 65.00 ± 9.02 | 64.39 ± 8.92 | 63.38 ± 10.35 | 0.740 |

| Male gender (%) | 60% | 60.97% | 70% | 0.590 |

| Smoking (%) | 57.5% | 46.34% | 65% | 0.234 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.53 ± 4.27 | 30.54 ± 6.31 | 30.45 ± 6.36 | 0.681 |

| DM(%) | 22.5% | 19.51% | 32.5% | 0.368 |

| AF (%) | 17.5% | 31.7% | 32.5% | 0.206 |

| CKD (%) | 15% | 26.82% | 20% | 0.426 |

| Aortic atherosclerosis (%) | 20% | 24.39% | 32.5% | 0.430 |

| Lipid biomarkers | ||||

| LDL-C | 74.11 ± 18.53 | 100.82 ± 19.62 | 132.29 ± 44.95 | 0.000 |

| HDL-C | 51.58 ± 12.98 | 44.84 ± 9.46 | 44.36 ± 14.90 | 0.027 |

| TC | 141.84 ± 24.62 | 159.89 ± 26.63 | 194.31 ± 50.44 | 0.000 |

| TG | 90.65 ± 39.06 | 100.73 ± 37.71 | 129.85 ± 61.73 | 0.001 |

| Non-HDLc | 84.78 ± 30.38 | 106.63 ± 36.32 | 146.20 ± 49.51 | 0.000 |

| Lp(a) | 10.60 ± 13.40 | 18.93 ± 22.76 | 22.06 ± 28.98 | 0.069 |

| log-Lp(a) | 2.02 ± 0.90 | 2.44 ± 1.06 | 2.49 ± 1.17 | 0.064 |

| ApoB | 58.53 ± 15.73 | 82.44 ± 12.71 | 103.83 ± 26.81 | 0.000 |

| R-ApoB | 0.324 ± 0.475 | 0.500 ± 0.507 | 0.579 ± 0.500 | 0.079 |

| ApoA | 142.05 ± 27.08 | 137.85 ± 21.80 | 123.03 ± 27.32 | 0.003 |

| LDL/ApoB | 1.31 ± 0.44 | 1.23 ± 0.24 | 1.28 ± 0.26 | 0.598 |

| Uric acid | 5.62 ± 1.79 | 6.58 ± 1.96 | 5.76 ± 1.40 | 0.201 |

| Creatinine | 0.924 ± 0.357 | 0.860 ± 0.185 | 0.858 ± 0.300 | 0.531 |

| eGFR | 85.91 ± 19.79 | 84.65 ± 17.29 | 88.80 ± 18.24 | 0.615 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||

| Gensini | 8.55 ± 19.60 | 14.57 ± 21.65 | 29.80 ± 27.78 | 0.000 |

| log-Gensini | 1.04 ± 1.40 | 1.91 ± 1.35 | 2.84 ± 1.28 | 0.000 |

| N-CAD | 22 (55%) | 9 (22%) | 2 (5%) | 0.000 |

| Single-vessel disease | 7 (17.5%) | 12 (29.3%) | 14 (35%) | 0.000 |

| Two-vessel disease | 9 (22.5%) | 12 (29.3%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Three-vessel disease | 2 (5%) | 8 (19.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| Left main disease | 2 (5%) | 3 (7.3%) | 8 (20%) | 0.031 |

| Biomarker | B | Std. Error | Standardized β | Adjusted R2 | p-Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apoB/apoA | 0.795 | 0.119 | 0.522 | 0.266 | 0.000 (0.559–1.030) |

| Constant | 1.932 | 0.119 | 0.000 (1.697–2.166) |

| Biomarker | OR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-CAD | 2.509 (1.441–4.369) | 0.186 | 0.001 |

| Three-vessel disease | 2.339 (1.427–3.892) | 0.162 | 0.001 |

| Left main disease | 2.771 (1.489–5.156) | 0.189 | 0.001 |

| OR (95% CI) | p-Value | Nagelkerke R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-CAD | |||

| Model 1 | 4.476 (2.498–9.022) | <0.001 | 0.443 |

| Model 2 | 4.149 (2.296–7.496) | <0.001 | 0.452 |

| Left main disease | |||

| Model 1 | 3.027 (1.404–6.526) | 0.005 | 0.351 |

| Model 2 | 2.949 (1.357–6.410) | 0.006 | 0.353 |

| Three-vessel disease | |||

| Model 1 | 2.481 (1.416–4.347) | 0.001 | 0.287 |

| Model 2 | 2.297 (1.297–4.067) | 0.004 | 0.307 |

| Biomarker | OR (95% CI) | Nagelkerke R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-CAD | 5.474 (1.550–19.326) | 0.300 | 0.008 |

| Three-vessel disease | 15.871 (2.194–114.805) | 0.481 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jigoranu, R.-A.; Mitu, O.; Oancea, A.F.; Miftode, R.-S.; Buburuz, A.M.; Bazyani, A.; Gavril, R.-S.; Stamate, T.-C.; Adam, C.A.; Miftode, I.-L.; et al. Diagnostic and Severity Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease Using ApoB/ApoA-I Ratio: Insights from a Statin-Treated Eastern European Cohort. Medicina 2026, 62, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020297

Jigoranu R-A, Mitu O, Oancea AF, Miftode R-S, Buburuz AM, Bazyani A, Gavril R-S, Stamate T-C, Adam CA, Miftode I-L, et al. Diagnostic and Severity Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease Using ApoB/ApoA-I Ratio: Insights from a Statin-Treated Eastern European Cohort. Medicina. 2026; 62(2):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020297

Chicago/Turabian StyleJigoranu, Raul-Alexandru, Ovidiu Mitu, Alexandru Florinel Oancea, Radu-Stefan Miftode, Ana Maria Buburuz, Amin Bazyani, Radu-Sebastian Gavril, Theodor-Constantin Stamate, Cristina Andreea Adam, Ionela-Larisa Miftode, and et al. 2026. "Diagnostic and Severity Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease Using ApoB/ApoA-I Ratio: Insights from a Statin-Treated Eastern European Cohort" Medicina 62, no. 2: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020297

APA StyleJigoranu, R.-A., Mitu, O., Oancea, A. F., Miftode, R.-S., Buburuz, A. M., Bazyani, A., Gavril, R.-S., Stamate, T.-C., Adam, C. A., Miftode, I.-L., Petris, A. O., Enache, I.-I. C., & Mitu, F. (2026). Diagnostic and Severity Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease Using ApoB/ApoA-I Ratio: Insights from a Statin-Treated Eastern European Cohort. Medicina, 62(2), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62020297