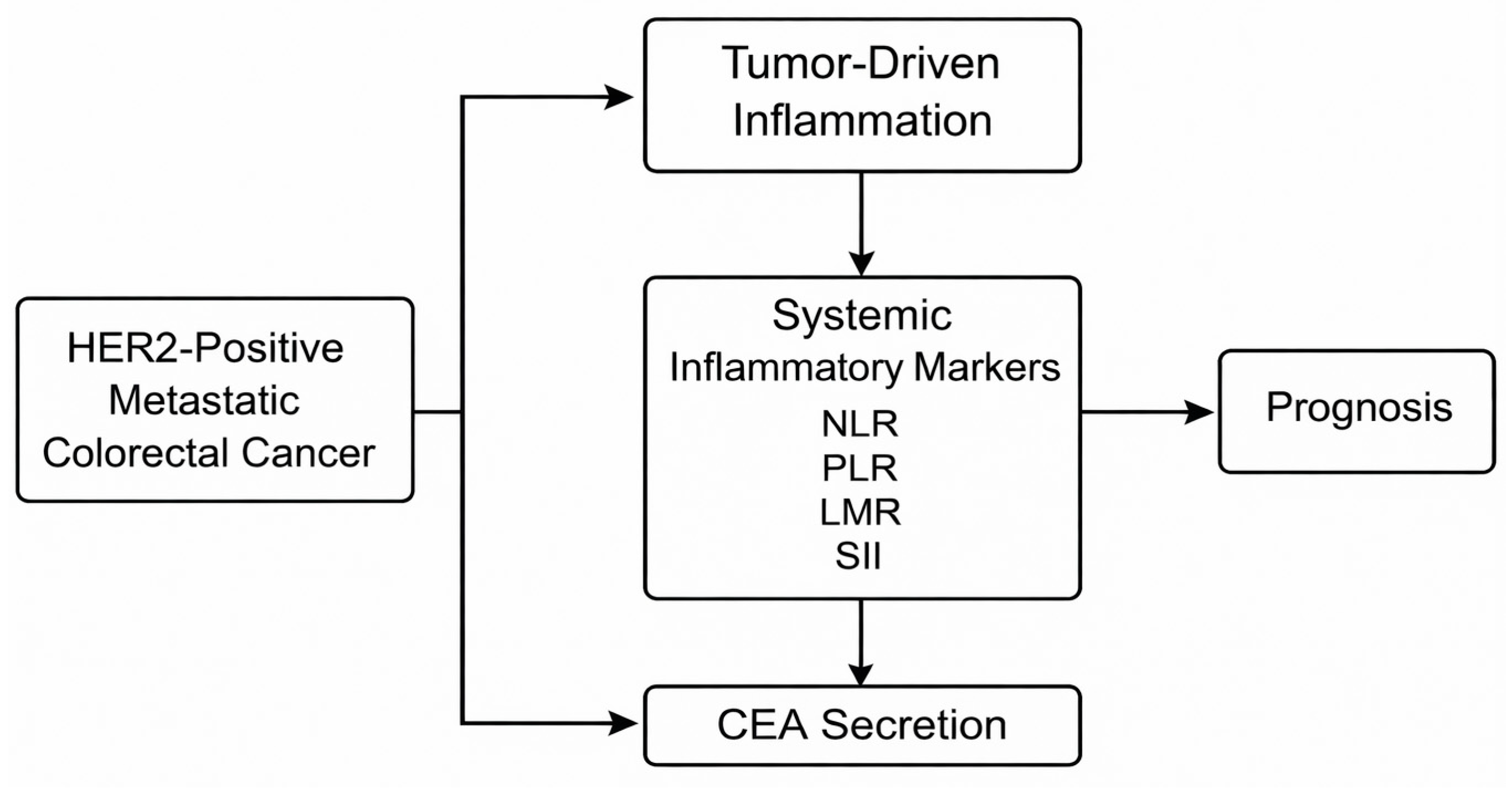

Significance of CEA Dynamics and Systemic Inflammatory Markers in HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing First-Line Chemotherapy: A Real-World Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

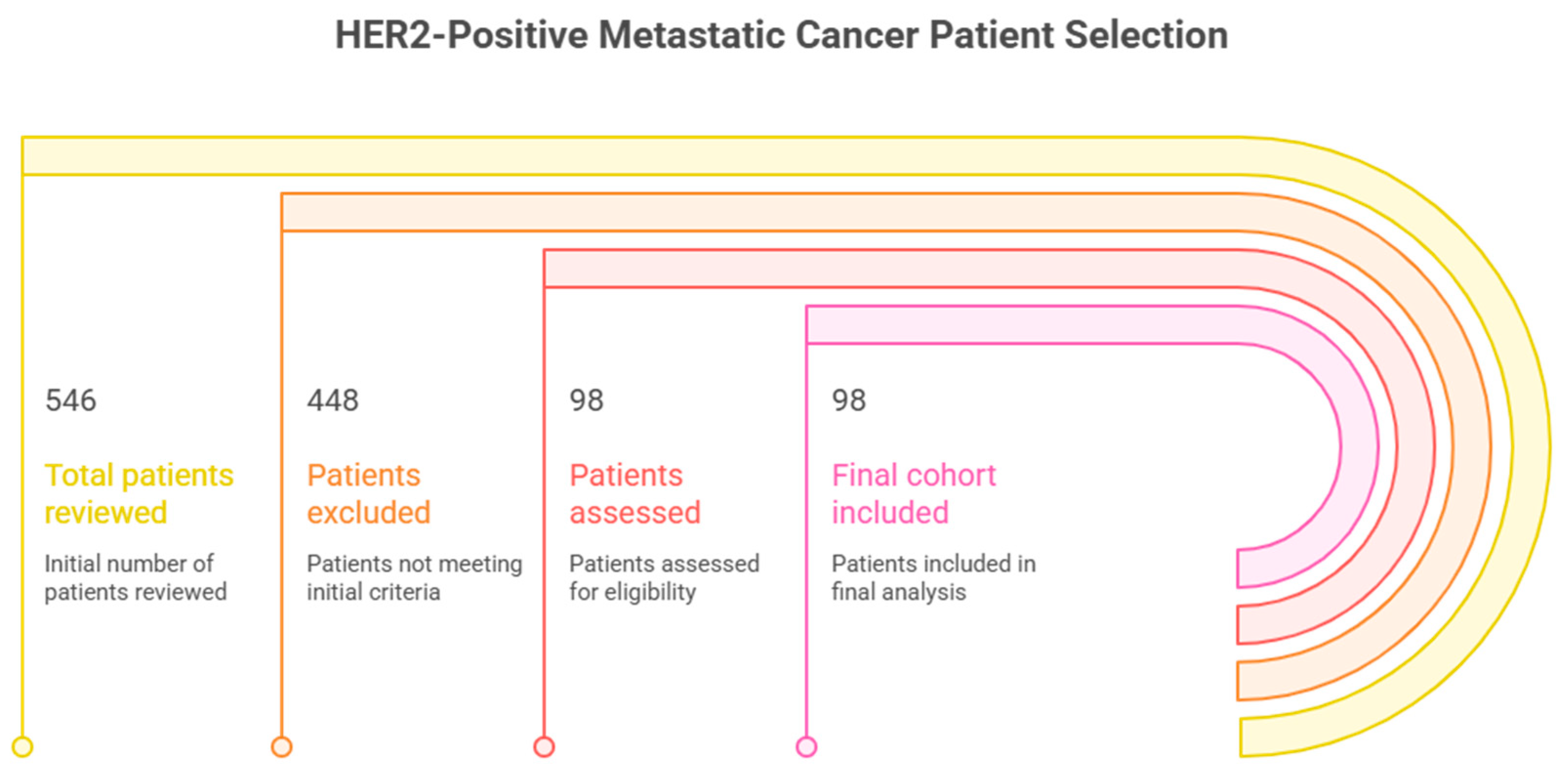

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Selection and Eligibility of Patients

- Age ≥ 18 years;

- Metastatic adenocarcinoma, which was histologically proven;

- IHC 3+ or FISH-amplified with an HER2/CEP17 ratio of more than 2.0;

- Access to the serial serum CEA;

- Access to complete blood count (NLR, PLR, LMR, SII, and computation);

- Receiving first-line chemotherapy (FOLFOX, XELOX, or FOLFIRI);

- ECOG performance status 0–2;

- Full follow-up data on progression-free survival.

- RAS or BRAF mutation;

- Second primary malignancy;

- Absence of HER2 testing;

- Missing data on inflammatory markers;

- Previous systemic chemotherapy;

- Alterations to inflammatory markers due to severe concurrent infection at baseline.

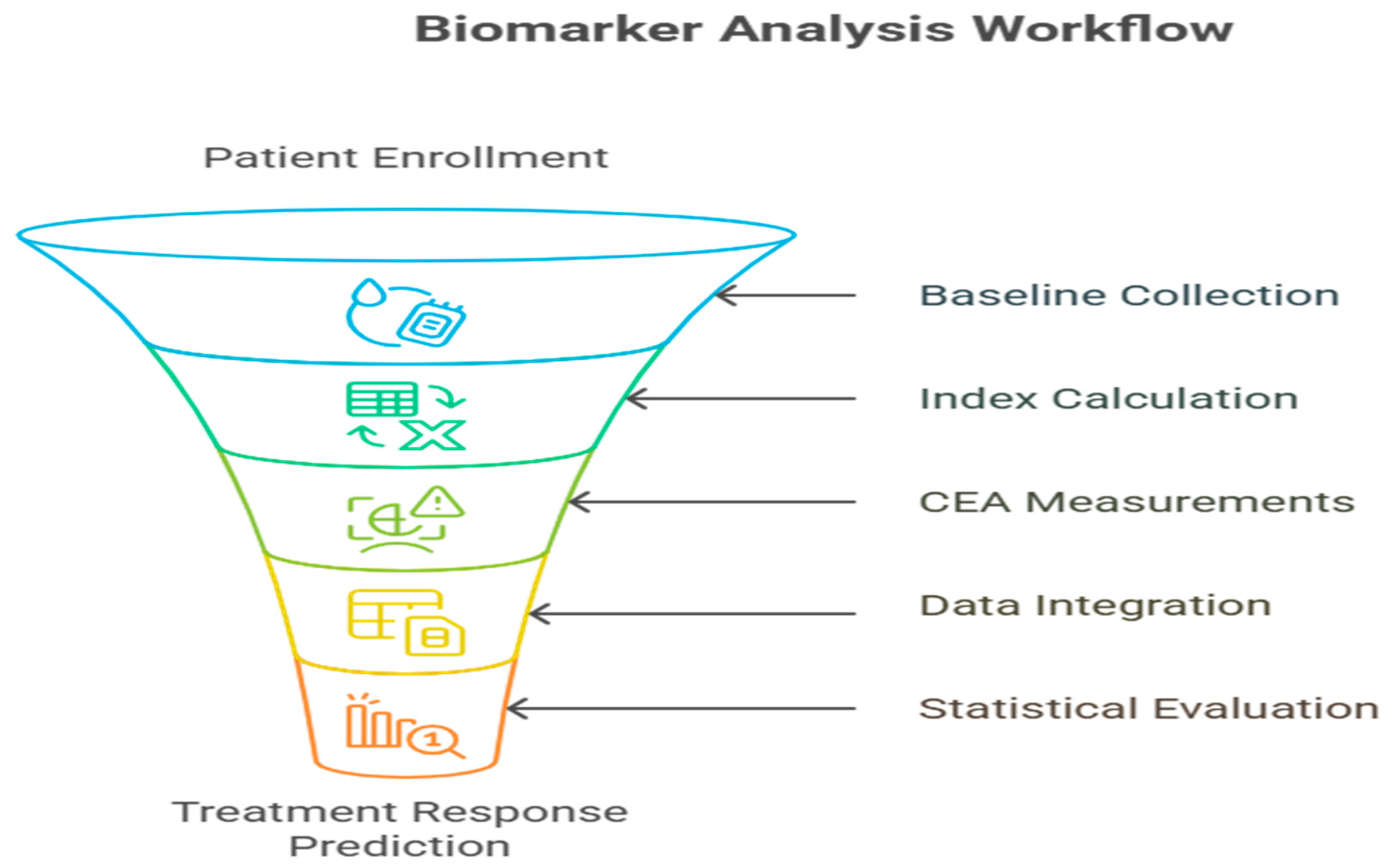

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

- Demographic variables: sex, age;

- Disease features: the location of the tumor, its metastases;

- Laboratory biomarkers: CEA baseline, CEA mid-treatment (cycle 3), CEA progression;

- Systemic inflammatory parameters: absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, mono- and platelet counts;

- Treatment information: use of chemotherapy, use of anti-EGFR (where available);

- Outcome measures: radiological response, day of progression, survival status.

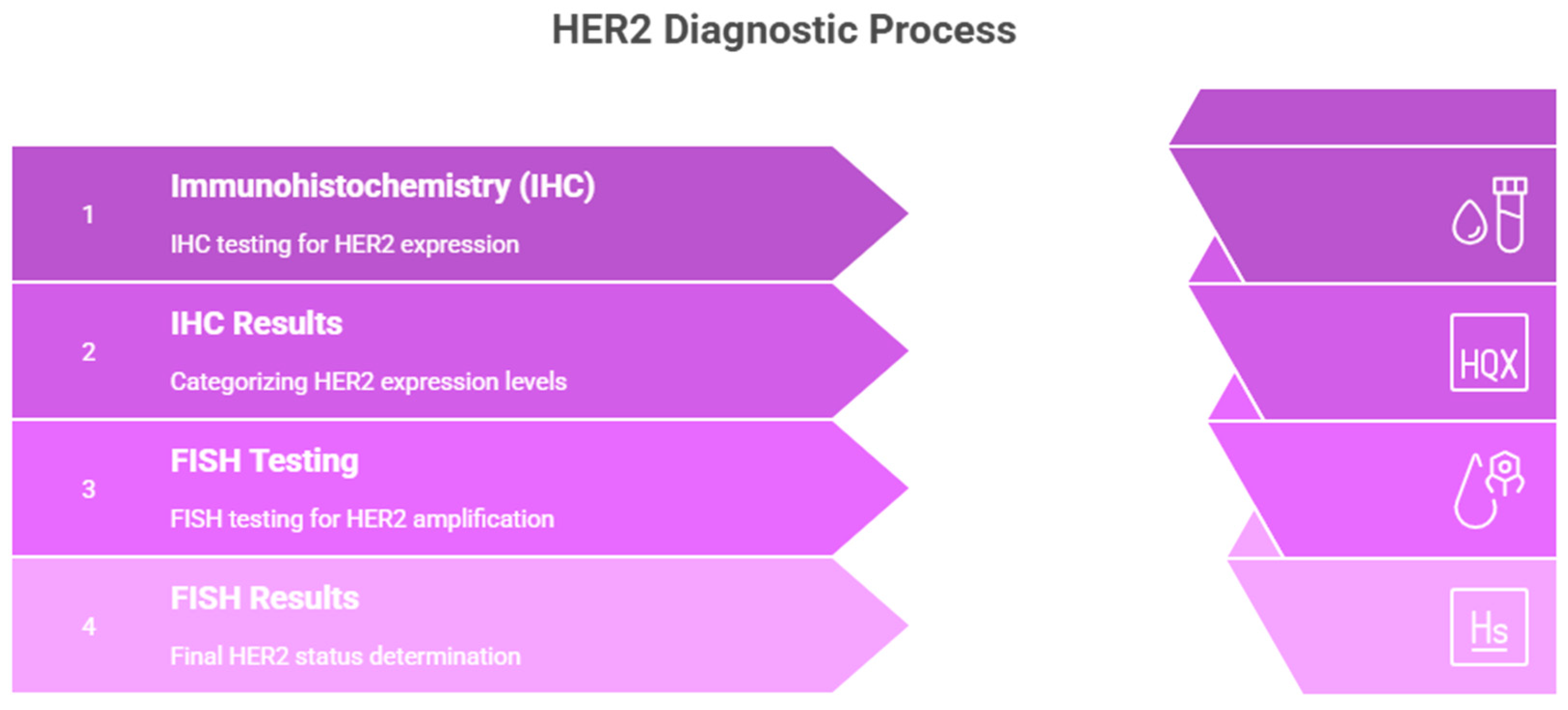

2.4. HER2 Assessment Workflow

2.4.1. IHC Scoring Criteria

- IHC 3+ (Positive):

- IHC 2+ (Equivocal):

- IHC 0/1+ (Negative):

2.4.2. FISH Positivity Criteria

- HER2/CEP17 ratio ≥ 2.0 AND average HER2 copy number ≥ 4.0 signals per cell.

2.5. Definition and Calculation of Systemic Inflammatory Markers

- Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR) = neutrophils/lymphocytes;

- Platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR) = platelets/lymphocytes;

- Lymphocyte/monocyte ratio (LMR) = lymphocytes/monocytes;

- Systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) = (neutrophils × platelets)/lymphocytes.

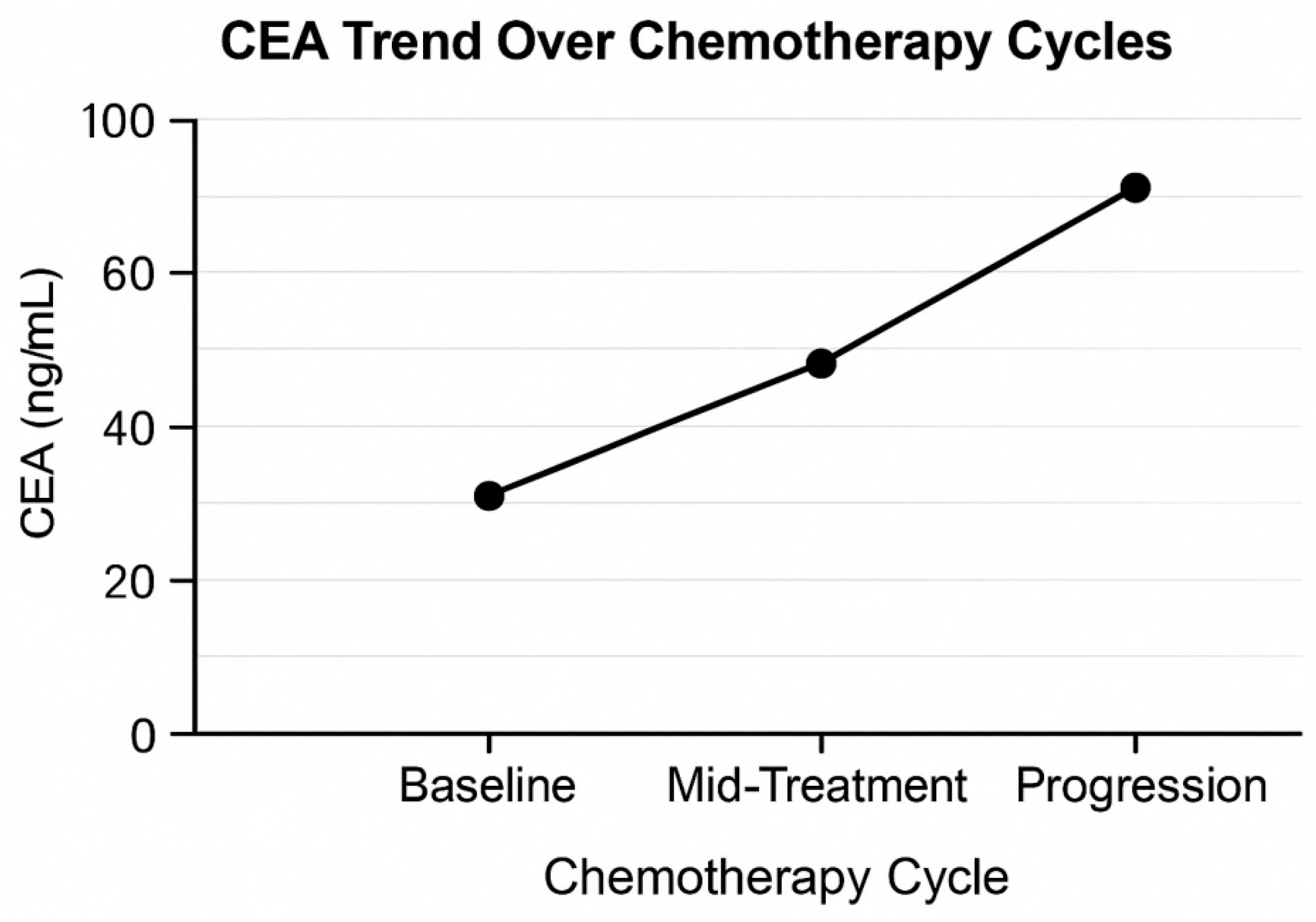

2.6. CEA Dynamics Assessment

- Baseline CEA: before the initial chemotherapy cycle;

- Treatment CEA—early: at the end of 6 weeks or three cycles;

- CEA at progression: progressive radiological validation.

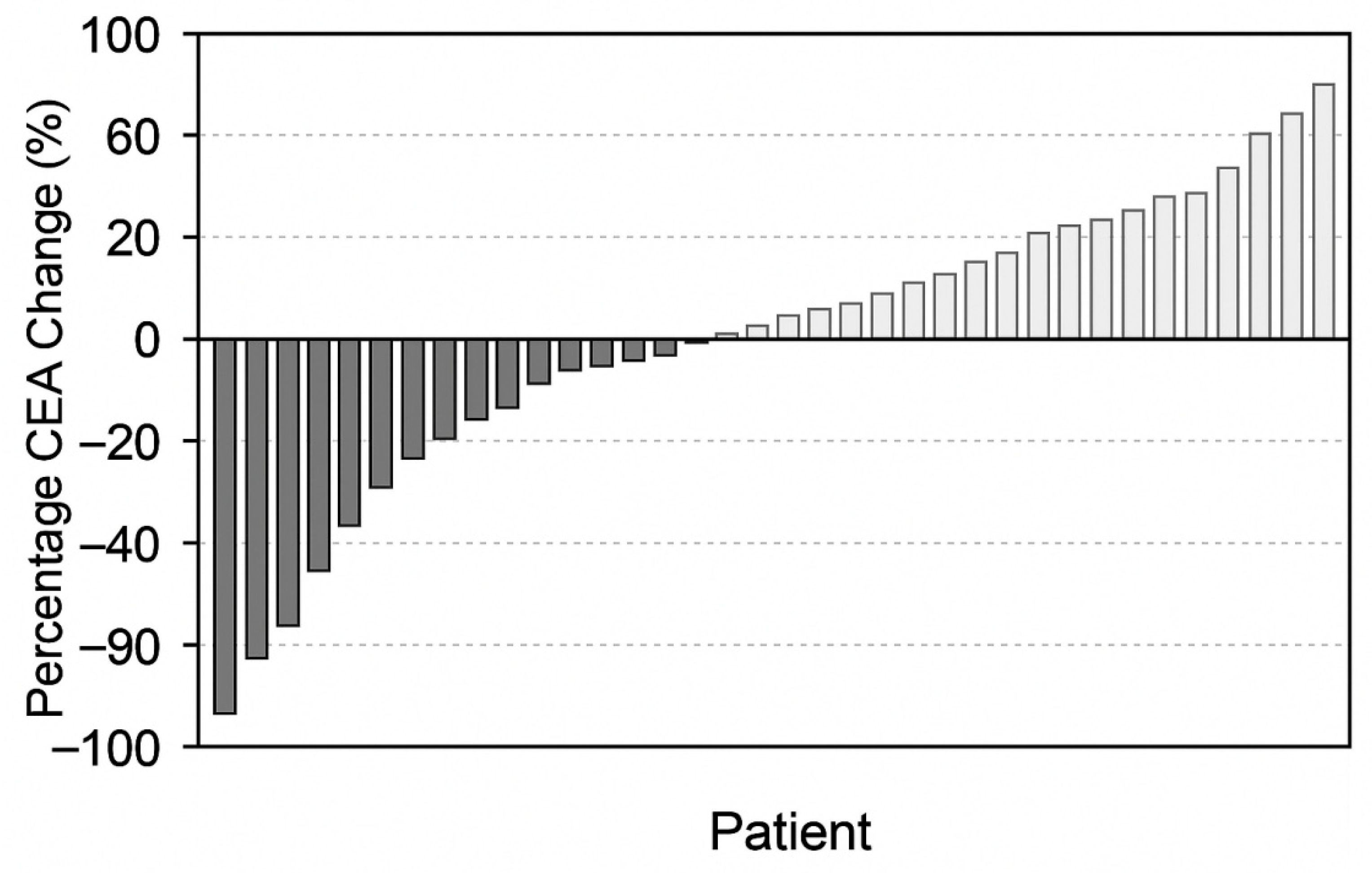

- DCEA (%) = (CEA_mid − CEA_baseline)/CEA_baseline) × 100.

- Major CEA decline: ≥50% reduction;

- Minor decline: 10–49%;

- CEA rise: >0% rise over the baseline.

2.7. Treatment Regimens

- FOLFOX: 5-FU + leucovorin + oxaliplatin;

- XELOX (CAPOX): Capecitabine + oxaliplatin;

- FOLFIRI 5-FU + leucovorin + irinotecan.

2.8. Study Endpoints

2.8.1. Primary Endpoint

- Correlation of CEA dynamics and progression-free survival (PFS).

2.8.2. Secondary Endpoints

- Inflammatory index (NLR, PLR, LMR, SII) prognostic value of PFS;

- Predictive performance of CEA + SIMs;

- Trends in response to early treatment.

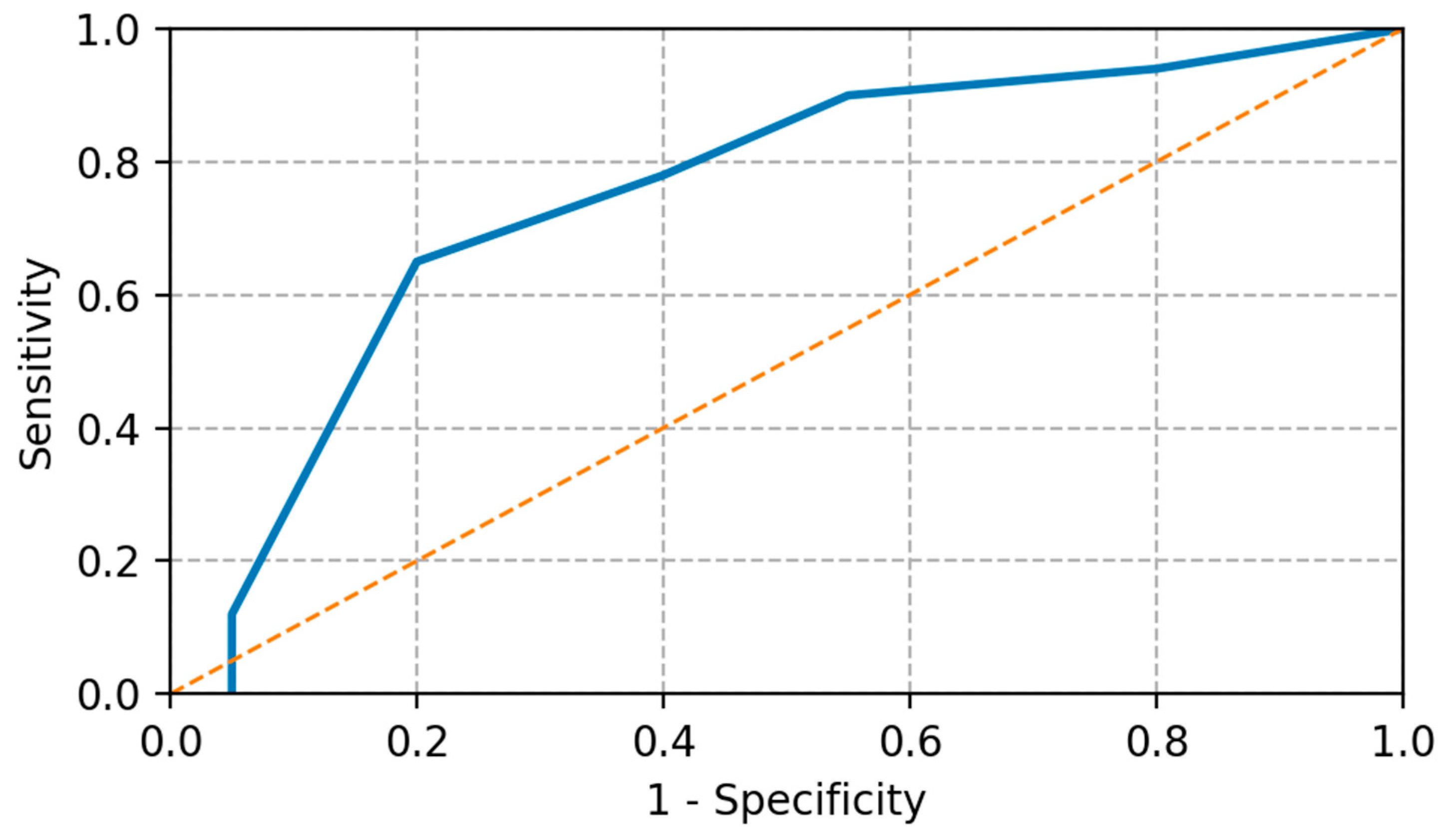

2.9. Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics: means, medians, and interquartile ranges;

- Comparison of groups: Chi-squared test, independent t-test, Mann–Whitney U test;

- CEA cutoff determination: optimal ROC curve analysis through the Youden index;

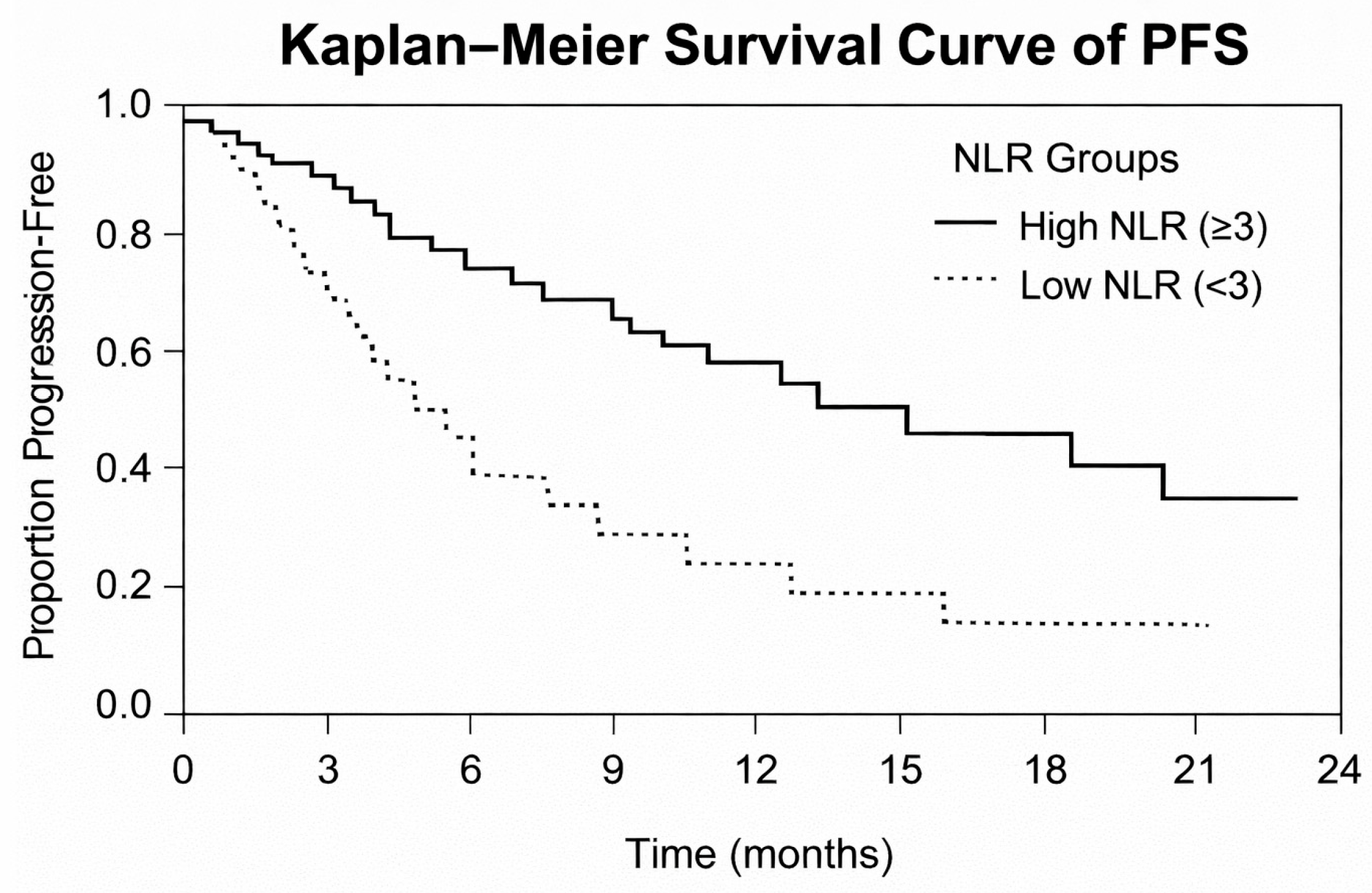

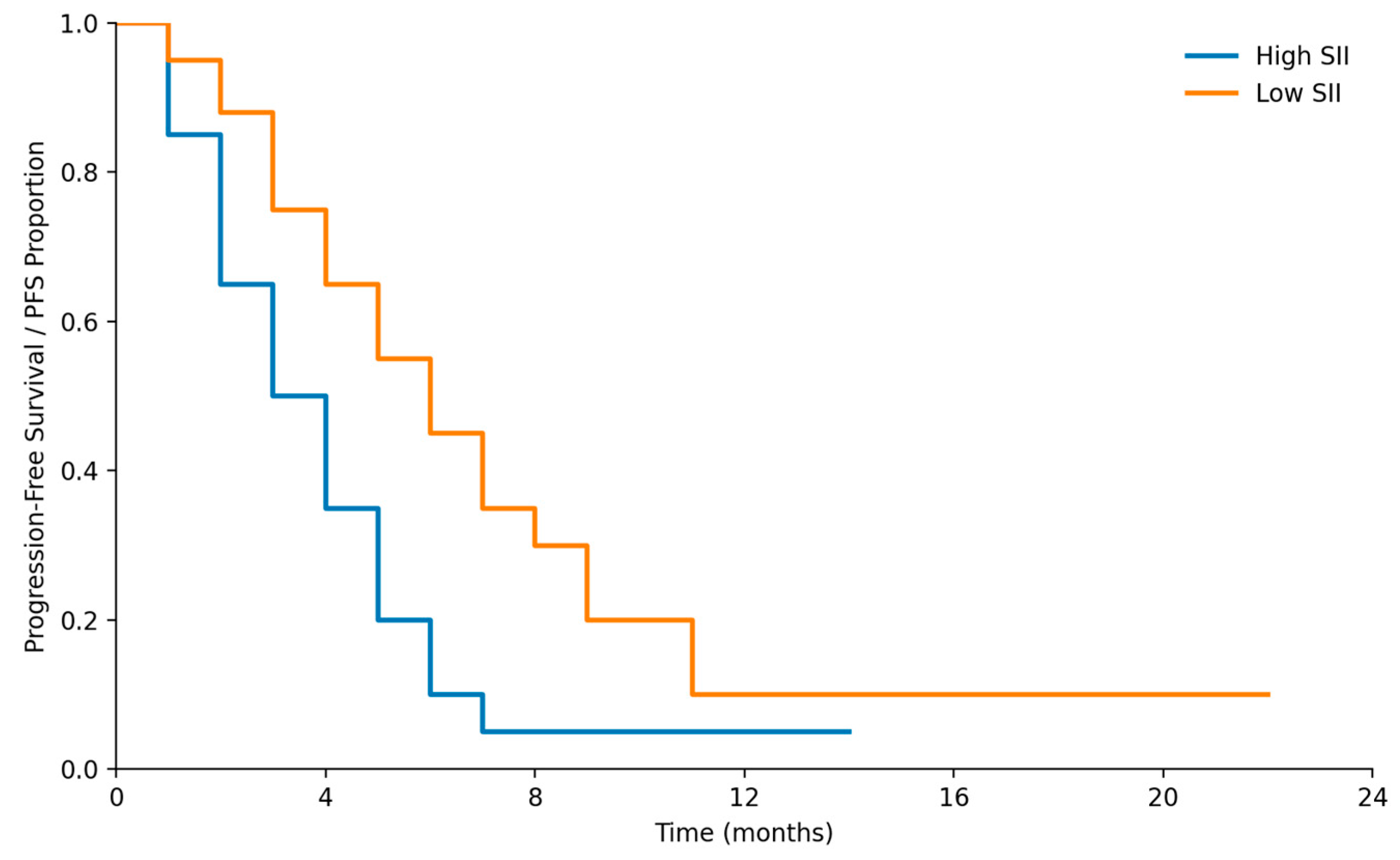

- Survival analysis: Kaplan–Meier curves, log-rank test;

- Restricted mean survival time (RMST) analysis was additionally performed with a prespecified truncation time (τ) of 12 months to provide a robust, model-free comparison of progression-free survival between groups (Figure 4).

2.10. Ethical Approval

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Study Cohort at Baseline

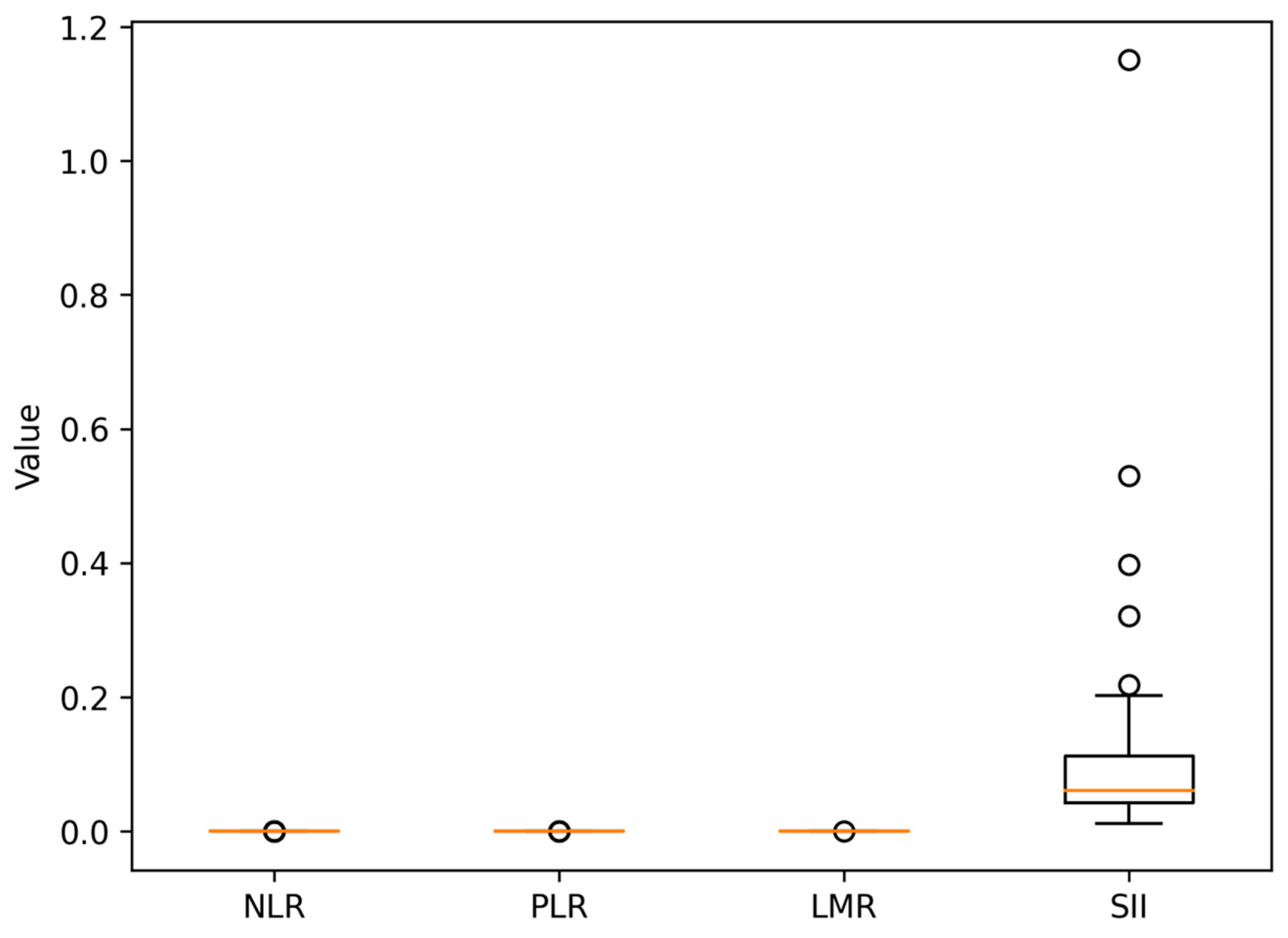

3.2. Data on Systemic Inflammatory Markers

- NLR: 3.4;

- PLR: 168;

- LMR: 3.1;

- SII: 890.

- High NLR ≥ 3;

- High PLR ≥ 150;

- Low LMR ≤ 2.5;

- High SII ≥ 900.

3.3. CEA Kinetics in the Overall Cohort (n = 98)

- Major decrease (≥50% decrease): 28 patients (28.6%);

- Minor decrease (10–49% decrease): 34 patients (34.7%);

- CEA increase (>0% rise): 36 patients (36.7%).

3.4. Correlation Between CEA Kinetics and Response to Treatment

3.5. Prognostic Value of Systemic Inflammatory Markers

- High NLR (≥3): median PFS = 5.2 months (95% CI: 4.1–6.3);

- Low NLR (<3): median PFS = 9.1 months (95% CI: 7.4–10.8);

- High SII (≥900): median PFS = 4.7 months (95% CI: 3.6–5.9);

- Low SII (<900): median PFS = 10.3 months (95% CI: 8.5–12.1).

3.6. Early CEA Kinetics in Evaluable Patients (n = 60)

3.7. Restricted Mean Survival Time (RMST) Analysis

3.8. Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of Significant Results

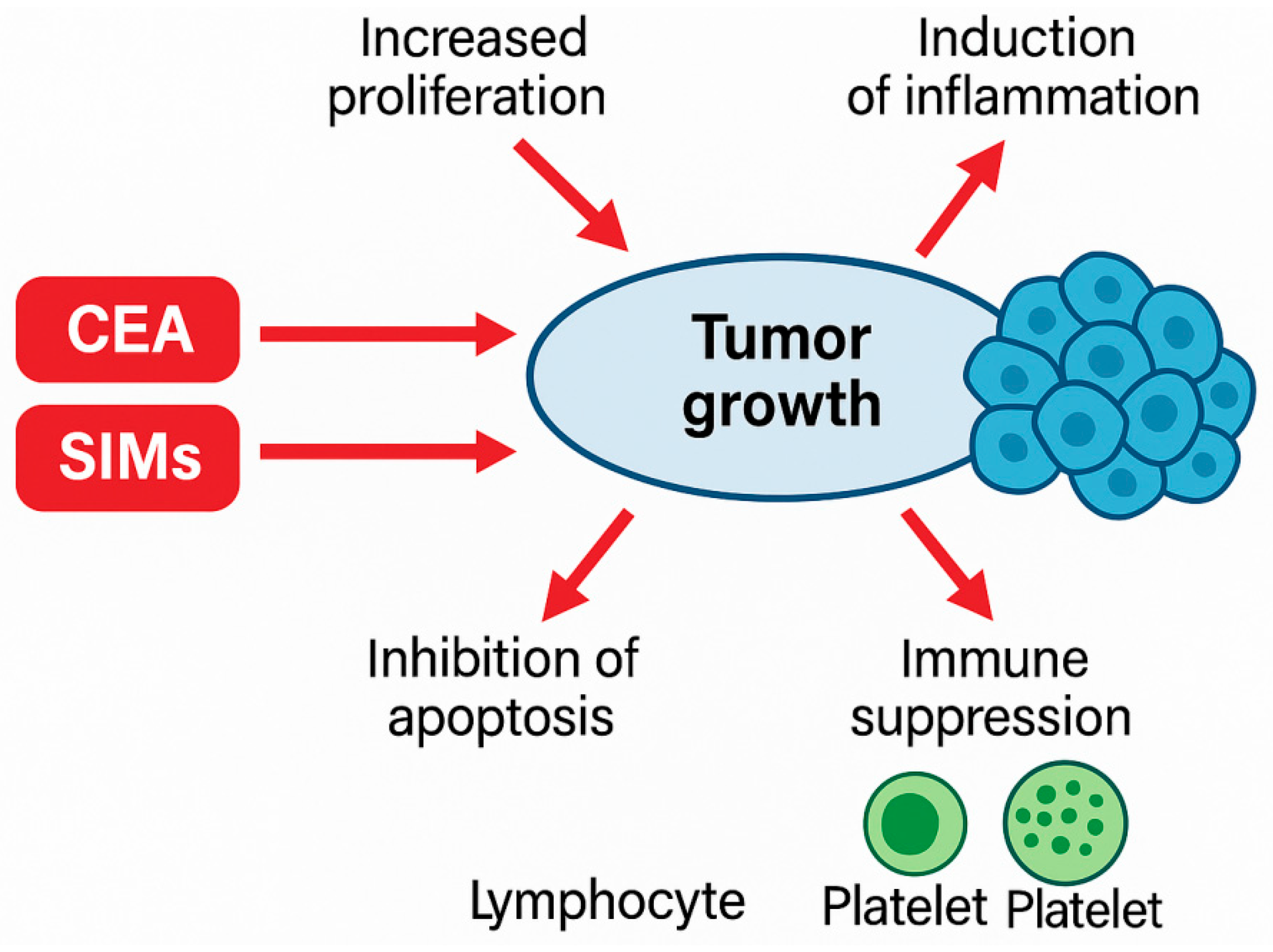

4.2. Biological Processes Underlying Noted Relations

- Amplified reactive oxygen species;

- Increased tumor angiogenesis;

- Disturbed immunological surveillance;

- Favored platelet–tumor cell interactions being pro-metastatic.

4.3. Comparison with the Existing Literature

4.4. Clinical Implications

- Increasing CEA detects risky patients at an early stage.

- This can lead to premature imaging, intensification of treatment, or reconsideration of the molecule.

- They are applicable in resource-constrained environments.

- Increased NLR/SII can be a reason to increase treatment follow-up.

- Patients with increasing CEA + elevated SII are under high risk of acute development.

- Such patients can be served by earlier switching to HER2-targeted therapies.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.5.1. Strengths

- Practical data from a Turkish oncology tertiary care center;

- Homogeneous cohort of HER2+;

- Extensive coverage of both CEA kinetics and several scores based on inflammation;

- Extended study period (2015–2024) enabling sound time-based assessment.

4.5.2. Limitations

- The retrospective design creates the possibility of selection bias.

- The size of the sample (n = 98) can be considered moderate, and some subgroup analyses might be restricted. Although the overall cohort size was sufficient for primary survival analyses, the relatively limited sample size may reduce the robustness of multivariable models and subgroup analyses adjusting for multiple confounders.

- There was a failure to monitor serial inflammatory markers after the baseline.

- Data derived from a single center may be a source of bias.

4.6. Future Research Directions

- Possible multicenter validation of predictive models of CEA + SIMs;

- The dynamic changes in inflammatory markers (not the baseline values) should be evaluated;

- Adding HER2-targeted therapies to biomarker-stratified trials;

- Implementation of the liquid biopsy (ctDNA, circulating HER2 copy number) to narrow down the predictive accuracy;

- Designing machine-learning-based prognostic models.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Wagle, N.S.; Cercek, A.; Smith, R.A.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germani, M.M.; Borelli, B.; Hashimoto, T.; Nakamura, Y.; Oldani, S.; Battaglin, F.; Bergamo, F.; Salvatore, L.; Stahler, A.; Antoniotti, C.; et al. Impact of Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated with Chemotherapy Plus Bevacizumab or Anti-EGFRs: Exploratory Analysis of Eight Randomized Trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3184–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Strickler, J.H.; Yoshino, T.; Graham, R.P.; Siena, S.; Bekaii-Saab, T. Diagnosis and Treatment of ERBB2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2022, 8, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Trusolino, S.; Martino, C.F.; Amatu, G.; Bardelli, F.; Siena, S. HER2 positivity predicts unresponsiveness to EGFR-targeted treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncology 2019, 24, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hurwitz, H.; Raghav, K.P.S.; McWilliams, R.R.; Fakih, M.; VanderWalde, A.; Swanton, C.; Kurzrock, R.; Burris, H.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab for HER2-amplified metastatic colorectal cancer (MyPathway): An updated report from a multicentre, open-label, phase 2a, multiple basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy-Chowdhuri, S.; Davies, K.D.; Ritterhouse, L.L.; Snow, A.N. ERBB2 (HER2) Alterations in Colorectal Cancer. J. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 24, 1064–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takegawa, N.; Yonesaka, K. HER2 as an Emerging Oncotarget for Colorectal Cancer Treatment After Failure of Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Therapy. Clin. Color. Cancer 2017, 16, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpelan-Holmström, M.; Haglund, C.; Lundin, J.; Järvinen, H.; Roberts, P. Pre-operative serum levels of CA 242 and CEA predict outcome in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 1996, 32, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibutani, M.; Maeda, K.; Nagahara, H.; Ohtani, H.; Sakurai, K.; Toyokawa, T.; Kubo, N.; Tanaka, H.; Muguruma, K.; Ohira, M.; et al. Significance of CEA and CA19-9 combination as a prognostic indicator and for recurrence monitoring in patients with stage II colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014, 7, 3753–3758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Zhou, M.; Qu, J.; Fu, L.; Li, X.; Cai, R.; Jin, B.; Teng, Y.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; et al. The dynamic monitoring of CEA in response to chemotherapy and prognosis of mCRC patients. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colloca, G.A.; Venturino, A.; Guarneri, D. Carcinoembryonic Antigen-related Tumor Kinetics After Eight Weeks of Chemotherapy is Independently Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2020, 19, e200–e207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.-H.; Zhai, E.-T.; Yuan, Y.-J.; Wu, K.-M.; Xu, J.-B.; Peng, J.-J.; Chen, C.-Q.; He, Y.-L.; Cai, S.-R. Systemic immune-inflammation index for predicting prognosis of colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6261–6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yang, F.-R.; Li, H.-L.; Hu, X.-W.; Sha, R.; Li, H.-J. Association between the systemic inflammation response index and mortality in cancer survivors based on NHANES 2001–2018. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N.; Li, J.; Yao, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Z.; Weng, S. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer liver metastasis: A meta-analysis of results from multivariate analysis. Int. J. Surg. 2022, 107, 106959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, J.; Xin, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, C.; Cheng, Y. Systemic immune-inflammation index, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio can predict clinical outcomes in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer treated with nivolumab. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2019, 33, e22964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Booth, C.M.; Karim, S.; Mackillop, W.J. Real-world data: Towards achieving the achievable in cancer care. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 16, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, C.M.; Tannock, I.F. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: Partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 551–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Loupakis, F.; Cremolini, C.; Salvatore, L.; Schirripa, M.; Lonardi, S.; Vaccaro, V.; Cuppone, F.; Giannarelli, D.; Zagonel, V.; Cognetti, F.; et al. Clinical impact of anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: Meta-analytical estimation and implications for therapeutic strategies. Cancer 2012, 118, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plebani, M. Errors in clinical laboratories or errors in laboratory medicine? Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2006, 44, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartley, A.N.; Washington, M.K.; Colasacco, C.; Ventura, C.B.; Ismaila, N.; Benson, A.B., 3rd; Carrato, A.; Gulley, M.L.; Jain, D.; Kakar, S.; et al. HER2 Testing and Clinical Decision Making in Gastroesophageal Adenocarcinoma: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists, American Society for Clinical Pathology, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 446–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton, A.J.; Mcnamara, M.G.; Šeruga, B.; Vera-Badillo, F.E.; Aneja, P.; Ocaña, A.; Leibowitz-Amit, R.; Sonpavde, G.; Knox, J.J.; Tran, B.; et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Chang, Q.; Meng, X.; Gao, N.; Wang, W. Prognostic value of Systemic immune-inflammation index in cancer: A meta-analysis. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 3295–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sørbye, H.; Dahl, O. Transient CEA increase at start of oxaliplatin combination therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol. 2004, 43, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic colorectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2022, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, W.; Lu, Z.; Lu, M.; Zhou, J.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Shen, L.; Li, J. Clinicopathological features of HER2 positive metastatic colorectal cancer and survival analysis of anti-HER2 treatment. BMC Cancer 2022, 22, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagisawa, M.; Sawada, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Fujii, S.; Yuki, S.; Komatsu, Y.; Yoshino, T.; Sakamoto, N.; Taniguchi, H. Prognostic Value and Molecular Landscape of HER2 Low-Expressing Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2021, 20, 113–120.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Huang, Y.; Lin, T. Prognostic impact of elevated pre-treatment systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) in hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e18571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Salfati, D.; Huot, M.; Aparicio, T.; Lepage, C.; Taieb, J.; Bouché, O.; Boige, V.; Phelip, J.-M.; Dahan, L.; Bennouna, J.; et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen kinetics predict response to first-line treatment in metastatic colorectal cancer: Analysis from PRODIGE 9 trial. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rad, N.M.; Sosef, O.; Seegers, J.; Koolen, L.J.E.R.; Hoofwijk, J.J.W.A.; Woodruff, H.C.; Hoofwijk, T.A.G.M.; Sosef, M.; Lambin, P. Prognostic models for colorectal cancer recurrence using carcinoembryonic antigen measurements. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1368120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp, M.A.; Cariolou, M.; Tzoulaki, I.; Aune, D.; Evangelou, E.; Berlanga-Taylor, A.J. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanicki-Caron, I.; Di Fiore, F.; Roque, I.; Astruc, E.; Stetiu, M.; Duclos, A.; Tougeron, D.; Saillard, S.; Thureau, S.; Benichou, J.; et al. Usefulness of the serum carcinoembryonic antigen kinetic for chemotherapy monitoring in patients with unresectable metastasis of colorectal cancer. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3681–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagai, Y.; Beppu, T.; Sakamoto, Y.; Miyamoto, Y.; Hayashi, H.; Nitta, H.; Imai, K.; Masuda, T.; Okabe, H.; Hirashima, K.; et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen half-life is an early predictor of therapeutic effects in induction chemotherapy for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Anticancer. Res. 2014, 34, 5529–5535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roxburgh, C.S.; McMillan, D.C. Role of systemic inflammatory response in predicting survival in patients with primary operable cancer. Future Oncol. 2009, 6, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, D.C. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: A decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013, 39, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amo, L.; Tamayo-Orbegozo, E.; Maruri, N.; Eguizabal, C.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Riñón, M.; Arrieta, A.; Santos, S.; Monge, J.; Vesga, M.A.; et al. Involvement of platelet-tumor cell interaction in immune evasion. Potential role of podocalyxin-like protein 1. Front Oncol. 2014, 4, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Venturini, J.; Massaro, G.; Lavacchi, D.; Rossini, D.; Pillozzi, S.; Caliman, E.; Pellegrini, E.; Antonuzzo, L. The emerging HER2 landscape in colorectal cancer: The key to unveil the future treatment algorithm? Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2024, 204, 104515, Erratum in: Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2024, 204, 104530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2024.104530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balkwill, F.; Mantovani, A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, T.; Soeth, E.; Czubayko, F.; Juhl, H. Inhibition of endogenous carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) increases the apoptotic rate of colon cancer cells and inhibits metastatic tumor growth. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2002, 19, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, C.; Clarke, L.; Pal, A.; Buchwald, P.; Eglinton, T.; Wakeman, C.; Frizelle, F. A Review of the Role of Carcinoembryonic Antigen in Clinical Practice. Ann. Coloproctol. 2019, 35, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sartore-Bianchi, A.; Trusolino, L.; Martino, C.; Bencardino, K.; Lonardi, S.; Bergamo, F.; Zagonel, V.; Leone, F.; Depetris, I.; Martinelli, E.; et al. Dual-targeted therapy with trastuzumab and lapatinib in treatment-refractory, KRAS codon 12/13 wild-type, HER2-positive metastatic colorectal cancer (HERACLES): A proof-of-concept, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cuyper, A.; Van Den Eynde, M.; Machiels, J.-P. HER2 as a Predictive Biomarker and Treatment Target in Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Color. Cancer 2020, 19, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaghi, C.; Tosi, F.; Mauri, G.; Bonazzina, E.; Amatu, A.; Bencardino, K.; Piscazzi, D.; Roazzi, L.; Villa, F.; Maggi, M.; et al. Targeting HER2 in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Current Therapies, Biomarker Refinement, and Emerging Strategies. Drugs 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category/Summary | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | — | 98 (100%) |

| Age (Years) | Median (Range) | 64 (37–85) |

| Sex | Male | 54 (54.8%) |

| Female | 44 (45.2%) | |

| Primary Tumor Location | Left-Sided | 63 (64.3%) |

| Right-Sided | 35 (35.7%) | |

| Metastatic Sites | Liver | 58 (59.2%) |

| Lung | 20 (20.4%) | |

| Peritoneum | 15 (15.3%) | |

| Bone/Other | 5 (5.1%) | |

| ECOG Performance Status | 0–1 | 94 (95.9%) |

| ≥2 | 4 (4.1%) | |

| HER2 Status Assessment | IHC 3+ | 71 (72.4%) |

| IHC 2+ with FISH+ | 27 (27.6%) | |

| Baseline CEA (ng/mL) | Median (Range) | 48 (3–742) |

| First-line Chemotherapy Regimen | FOLFOX | 51 (52.0%) |

| XELOX (CAPOX) | 33 (33.7%) | |

| FOLFIRI | 14 (14.3%) |

| Inflammatory Marker | Median | Interquartile Range (IQR) | Cutoff Used | Patients Above Cutoff n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR) | 3.4 | 2.2–5.1 | ≥3 | 56 (57.1%) |

| Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio (PLR) | 168 | 124–241 | ≥150 | 63 (64.3%) |

| Lymphocyte-to-Monocyte Ratio (LMR) | 3.1 | 2.0–4.3 | ≤2.5 | 29 (29.6%) |

| Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index (SII) | 890 | 640–1280 | ≥900 | 52 (53.1%) |

| Biomarker | Group | n | RMST (Months) | 95% CI | RMST Difference (Months) | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEA kinetics | Early increase | 18 | 8.71 | 7.40–10.02 | −0.04 | −1.69 to 1.61 | 0.961 |

| No increase | 42 | 8.75 | 7.75–9.75 | Reference | — | — | |

| NLR | High | 23 | 9.09 | 7.79–10.39 | +0.57 | −0.96 to 2.10 | 0.469 |

| Low | 61 | 8.52 | 7.72–9.33 | Reference | — | — | |

| SII | High | 84 | 8.68 | 7.99–9.37 | −2.25 | −3.71 to −0.79 | 0.002 |

| Low | 14 | 10.93 | 9.64–12.22 | Reference | — | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ozkerim, U.; Kinikoglu, O.; Oksuz, S.; Isik, D.; Altintas, Y.E.; Yildirim, S.; Akdag, G.; Surmeli, H.; Odabas, H.; Basoglu, T.; et al. Significance of CEA Dynamics and Systemic Inflammatory Markers in HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing First-Line Chemotherapy: A Real-World Cohort Study. Medicina 2026, 62, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010099

Ozkerim U, Kinikoglu O, Oksuz S, Isik D, Altintas YE, Yildirim S, Akdag G, Surmeli H, Odabas H, Basoglu T, et al. Significance of CEA Dynamics and Systemic Inflammatory Markers in HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing First-Line Chemotherapy: A Real-World Cohort Study. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleOzkerim, Ugur, Oguzcan Kinikoglu, Sila Oksuz, Deniz Isik, Yunus Emre Altintas, Sedat Yildirim, Goncagul Akdag, Heves Surmeli, Hatice Odabas, Tugba Basoglu, and et al. 2026. "Significance of CEA Dynamics and Systemic Inflammatory Markers in HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing First-Line Chemotherapy: A Real-World Cohort Study" Medicina 62, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010099

APA StyleOzkerim, U., Kinikoglu, O., Oksuz, S., Isik, D., Altintas, Y. E., Yildirim, S., Akdag, G., Surmeli, H., Odabas, H., Basoglu, T., & Turan, N. (2026). Significance of CEA Dynamics and Systemic Inflammatory Markers in HER2-Positive Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Undergoing First-Line Chemotherapy: A Real-World Cohort Study. Medicina, 62(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010099