Heart Failure Outcomes with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

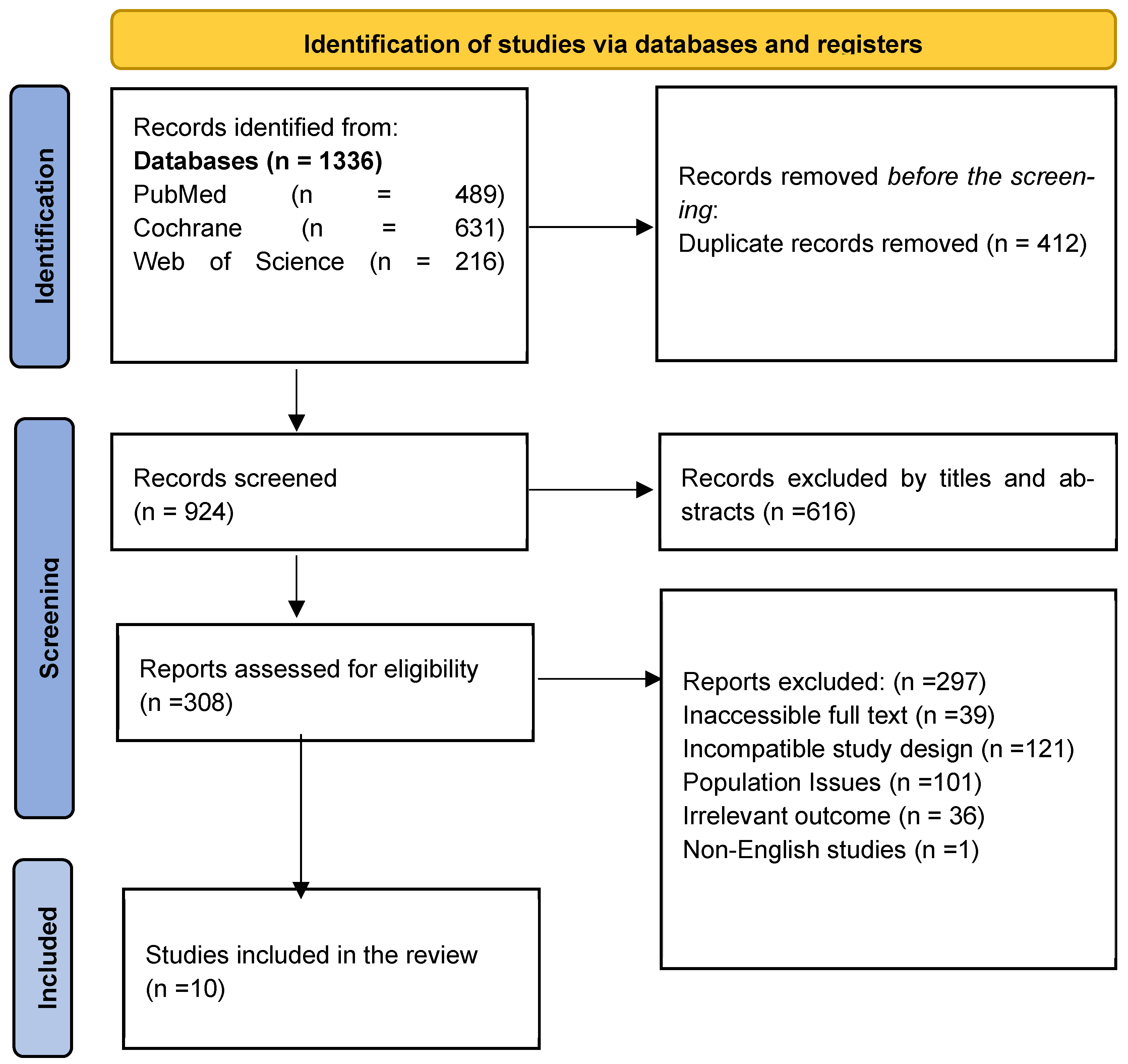

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

2.2. Selection of Articles

2.3. Data Extraction

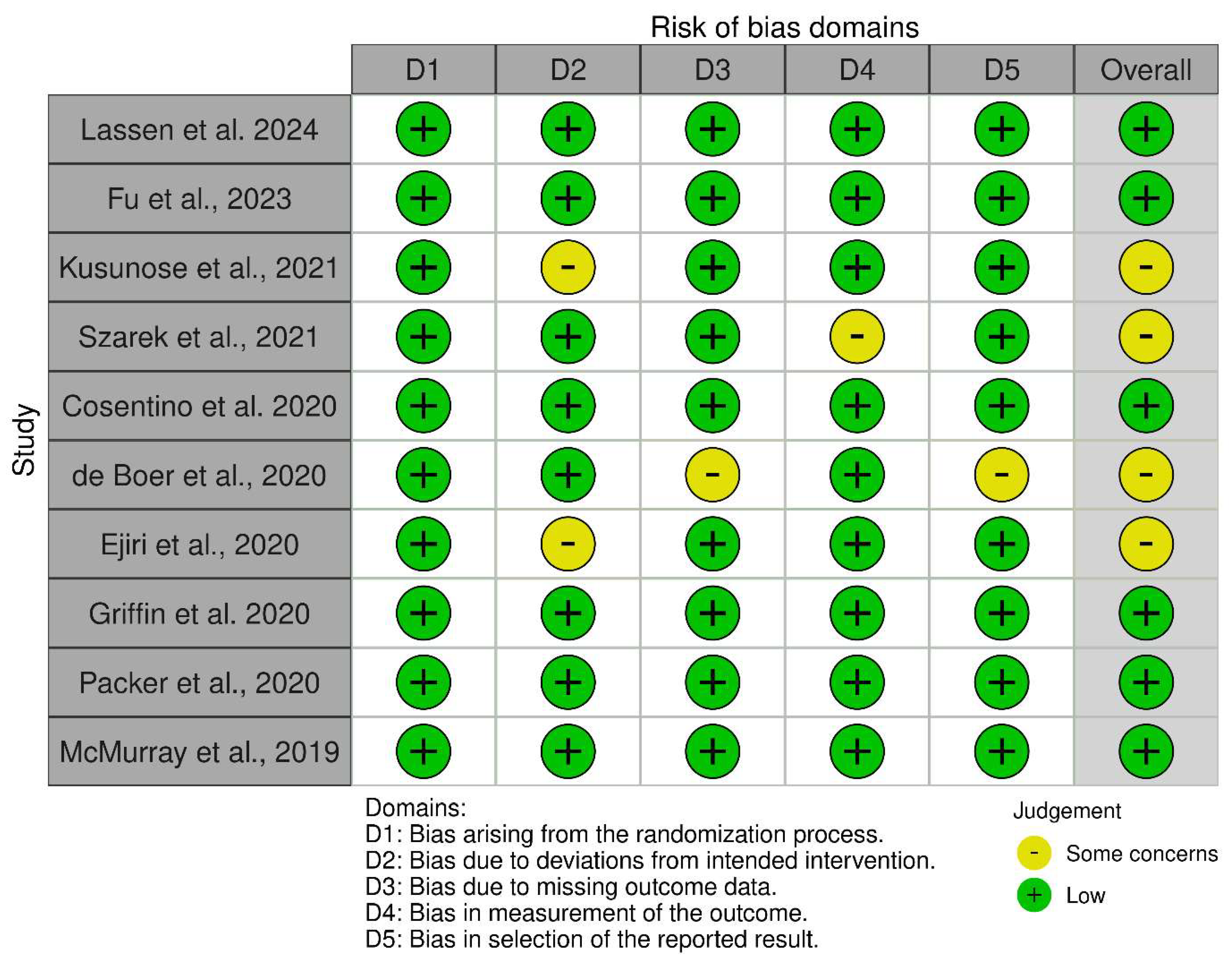

2.4. Quality Assessment

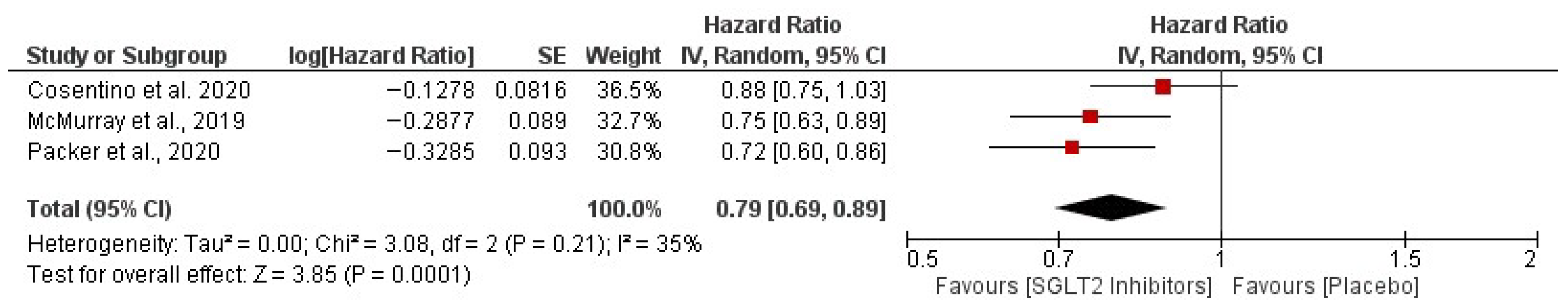

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, M.R.; Petrie, M.C.; Varyani, F.; Ostergren, J.; Michelson, E.L.; Young, J.B.; Solomon, S.D.; Granger, C.B.; Swedberg, K.; Yusuf, S.; et al. Impact of diabetes on outcomes in patients with heart failure according to left ventricular systolic function. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 1377–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.D.; Langenberg, C.; Rapsomaniki, E.; Denaxas, S.; Pujades-Rodriguez, M.; Gale, C.P.; Deanfield, J.; Smeeth, L.; Timmis, A.; Hemingway, H. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: A cohort study in 1.9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015, 3, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannel, W.B.; McGee, D.L. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Study. JAMA 1979, 241, 2035–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender, M.A.; Steg, P.G.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; Eagle, K.; Ohman, E.M.; Goto, S.; Kuder, J.; Im, K.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Bhatt, D.L. Impact of diabetes mellitus on hospitalization for heart failure, cardiovascular events, and death: Outcomes at 4 years from the REACH Registry. Circulation 2015, 132, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, G.A.; Hillier, T.A.; Erbey, J.R.; Brown, J.B. Congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: Prevalence, incidence3, and risk factors. Diabetes Care 2001, 24, 1614–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, K.; DeVore, A.D.; Wu, J.; Matsouaka, R.A.; Fonarow, G.C.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Yancy, C.W.; Green, J.B.; Altman, N.; Hernandez, A.F. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and diabetes: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurray, J.J.V.; Solomon, S.D.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Køber, L.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Martinez, F.A.; Ponikowski, P.; Sabatine, M.S.; Anand, I.S.; Bělohlávek, J.; et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1995–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; McMurray, J.J.V. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: A state-of-the-art review. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonora, B.M.; Avogaro, A.; Fadini, G.P. Extraglycemic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors: A review of the evidence. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M. SGLT2 inhibitors produce cardiorenal benefits by promoting adaptive cellular reprogramming to induce a state of fasting mimicry: A paradigm shift. Diabetes Care 2020, 43, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima, Y. SGLT2 inhibitors play a salutary role in heart failure via modulation of mitochondrial function. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 6, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinman, B.; Wanner, C.; Lachin, J.M.; Fitchett, D.; Bluhmki, E.; Hantel, S.; Mattheus, M.; Devins, T.; Johansen, O.E.; Woerle, H.J.; et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2117–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, B.; Perkovic, V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; de Zeeuw, D.; Fulcher, G.; Erondu, N.; Shaw, W.; Law, G.; Desai, M.; Matthews, D.R.; et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 644–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiviott, S.D.; Raz, I.; Bonaca, M.P.; Mosenzon, O.; Kato, E.T.; Cahn, A.; Silverman, M.G.; Zelniker, T.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Murphy, S.A.; et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Pocock, S.J.; Carson, P.; Januzzi, J.; Verma, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Brueckmann, M.; et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1413–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anker, S.D.; Butler, J.; Filippatos, G.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bocchi, E.; Böhm, M.; Brunner-La Rocca, H.P.; Choi, D.J.; Chopra, V.; Chuquiure-Valenzuela, E.; et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1451–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.D.; McMurray, J.J.; Claggett, B.; de Boer, R.A.; DeMets, D.; Hernandez, A.F.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.; Martinez, F.; et al. Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Szarek, M.; Steg, P.G.; Cannon, C.P.; Leiter, L.A.; McGuire, D.K.; Lewis, J.B.; Riddle, M.C.; Voors, A.A.; Metra, M.; et al. Sotagliflozin in patients with diabetes and recent worsening heart failure. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Gardner, R.S.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Butler, J.; Čelutkienė, J.; Chioncel, O.; et al. 2023 focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3627–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2023. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S1–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer Program]. Version 5.4.1. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2020. Available online: https://revman.cochrane.org (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Lassen, M.C.; Ostrominski, J.W.; Inzucchi, S.E.; Claggett, B.L.; Kulac, I.; Jhund, P.; de Boer, R.A.; Hernandez, A.F.; Kosiborod, M.N.; Lam, C.S.; et al. Effect of dapagliflozin in patients with diabetes and heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction according to background glucose-lowering therapy: A pre-specified analysis of the DELIVER trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Fan, Y.; Liu, F.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Cheng, L. Effect of SGLT-2 inhibitor, dapagliflozin, on left ventricular remodeling in patients with type 2 diabetes and HFrEF. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2023, 23, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunose, K.; Imai, T.; Tanaka, A.; Dohi, K.; Shiina, K.; Yamada, T.; Kida, K.; Eguchi, K.; Teragawa, H.; Takeishi, Y.; et al. Effects of canagliflozin on NT-proBNP stratified by left ventricular diastolic function in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic heart failure: A sub analysis of the CANDLE trial. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2021, 20, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Steg, P.G.; Cannon, C.P.; Leiter, L.A.; McGuire, D.K.; Lewis, J.B.; Riddle, M.C.; Voors, A.A.; Metra, M.; et al. Effect of sotagliflozin on total hospitalizations in patients with type 2 diabetes and worsening heart failure: A randomized trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2021, 174, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosentino, F.; Cannon, C.P.; Cherney, D.Z.; Masiukiewicz, U.; Pratley, R.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Frederich, R.; Charbonnel, B.; Mancuso, J.; Shih, W.J.; et al. Efficacy of Ertugliflozin on Heart Failure-Related Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: Results of the VERTIS CV Trial. Circulation 2020, 142, 2205–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, R.A.; Núñez, J.; Kozlovski, P.; Wang, Y.; Proot, P.; Keefe, D. Effects of the dual sodium-glucose linked transporter inhibitor, licogliflozin vs. placebo or empagliflozin in patients with type 2 diabetes and heart failure. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejiri, K.; Miyoshi, T.; Kihara, H.; Hata, Y.; Nagano, T.; Takaishi, A.; Toda, H.; Nanba, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Akagi, S.; et al. Effect of luseogliflozin on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e015103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.; Rao, V.S.; Ivey-Miranda, J.; Fleming, J.; Mahoney, D.; Maulion, C.; Suda, N.; Siwakoti, K.; Ahmad, T.; Jacoby, D.; et al. Empagliflozin in heart failure: Diuretic and cardiorenal effects. Circulation 2020, 142, 1028–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, D.K.; Shih, W.J.; Cosentino, F.; Charbonnel, B.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Dagogo-Jack, S.; Pratley, R.; Greenberg, M.; Wang, S.; Huyck, S.; et al. Association of SGLT2 Inhibitors With Cardiovascular and Kidney Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2021, 6, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.Y.; Pan, H.C.; Shiao, C.C.; Chuang, M.H.; See, C.Y.; Yeh, T.H.; Yang, Y.; Chu, W.K.; Wu, V.C. Impact of SGLT2 inhibitors on patient outcomes: A network meta-analysis. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Bhatia, K.; Kapoor, A.; Badimon, J.; Pinney, S.P.; Mancini, D.M.; Santos-Gallego, C.G.; Lala, A. SGLT2 inhibitors, functional capacity, and quality of life in patients with heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e241234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apperloo, E.M.; Neuen, B.L.; Fletcher, R.A.; Jongs, N.; Anker, S.D.; Bhatt, D.L.; Butler, J.; Cherney, D.Z.I.; Herrington, W.G.; Inzucchi, S.E.; et al. Efficacy and safety of SGLT2 inhibitors with and without glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists: A SMART-C collaborative meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024, 12, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudoran, C.; Tudoran, M.; Giurgi-Oncu, C.; Abu-Awwad, A.; Abu-Awwad, S.-A.; Voiţa-Mekereş, F. Associations between oral glucose-lowering agents and increased risk for life-threatening arrhythmias in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus—A literature review. Medicina 2023, 59, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, A.; Pandozi, C.; Bonanni, M.; Mariani, M.V.; Sgarra, L.; Nesti, L.; Pierucci, N.; La Fazia, V.M.; Lavalle, C.; Nardi, F.; et al. Impact of empagliflozin and dapagliflozin on sudden cardiac death: A systematic review and meta-analysis of adjudicated randomized evidence. Heart Rhythm, 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study (Author, Year) | Study Design, Country | Sample Size (N) | Mean Age | Gender (M/F) | Diabetes Status | HF Criteria | Intervention Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lassen et al. 2024 [25] | RCT, double-blinded, multinational | 3150 participants with T2D at baseline | 71.0 ± 9.1 years | 57.7% Male/42.3% Female | History of diabetes, prevalent glucose-lowering therapy, or HbA1c ≥ 6.5% at baseline. | LVEF > 40%, NYHA: II-IV, elevated NT-proBNP, structural heart disease | Dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily Added to the standard of care, with a median follow-up of 4 years. |

| Fu et al., 2023 [26] | RCT, double-blinded, in China | 60 (Dapagliflozin group: 30 patients, Placebo group: 30 patients) | 61.6 ± 8.2 years | 43/17 | A confirmed diagnosis of T2DM |

| Dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily for 12 months vs. Placebo |

| Kusunose et al., 2021 [27] | Randomized, multicenter, open-label with blinded endpoint assessment; Japan (34 centers) | 233 (Canagliflozin 113; Glimepiride 120) | 69 ± 9 years | Canagliflozin: 88 M/25 F; Glimepiride: 86 M/34 F | T2DM | Chronic HF; NYHA I-III | Add-on Canagliflozin (100 mg) verus Glimepiride (0.5 mg); 24 weeks; primary endpoint NT-proBNP change |

| Szarek et al., 2021 [28] | RCT, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial; international [306 sites in 32 countries] | 1222 (Sotagliflozin: 608; Placebo: 614) | Median (IQR) 66 years (Sotagliflozin: 69 (63–73); Placebo: 70 (64–76) | (Sotagliflozin: 410/198; Placebo: 400/214) | T2DM | Recent worsening HF | Sotagliflozin 200 mg/day (titrated to 400 mg/day) vs. placebo; median follow-up: 9 months |

| Cosentino et al., 2020 [29] | RCT double-blinded, multicenter trial | 8246 T2DM with ASCVD patients (Ertugliflozin 5499; Placebo 2747) | 64.4 years | 5777/2469 | T2DM with HbA1c 7.0–10.5% + ASCVD | Hospitalization ≥ 24 h + signs/symptoms + objective evidence | Ertugliflozin 5 or 15 mg OD; follow-up median 3.0 years vs. placebo |

| de Boer et al., 2020 [30] | RCT double-blinded, multicenter, international trial | 125 T2DM with HF (Licogliflozin groups:62; Empagliflozin:30; Placebo:33) | Median Lico: 2.5 mg: 70 10 mg: 72.5 50 mg: 66 Empa (25 mg): 68.5 Placebo: 71 | 89/35 | T2DM with HF (NYHA II-IV; NT-proBNP >300 pg/mL) | HF with NYHA II-IV Elevated NT-proBNP | Licogliflozin 2.5/10/50 mg OD verus Empagliflozin 25 mg OD vs. Placebo; 12 weeks |

| Ejiri et al., 2020 [31] | RCT, open-label, Multicenter | 169 T2DM with HFpEF (Luseogliflozin: 86 Voglibose: 83) | Luseogliflozin: 71.7 ± 7.7 years, Voglibose: 74.6 ± 7.7 years | 103/66 | T2DM | HFpEF (LVEF > 45%; BNP ≥ 35 pg/mL) | Luseogliflozin 2.5 mg OD versus Voglibose 0.2 mg TDS; 12 weeks |

| Griffin et al., 2020 [32] | RCT, double-blinded, crossover trial in the United States | 20 patients analyzed (21 randomized, one excluded) | 60 ± 12 years | 15/5 | T2DM (Median HbA1c 7.1%) |

| Empagliflozin 10 mg once daily for 14 days, crossover design with placebo, separated by a 14-day washout; intensive phenotyping at baseline and end. |

| Packer et al., 2020 [16] | RCT, double-blinded, multicenter, international (520 centers in 20 countries) | 3730 patients (Empagliflozin: 1863; Placebo: 1867) | Empagliflozin: 67.2 ± 10.8; Placebo: 66.5 ± 11.2 | Empagliflozin: 1426 M/437 F Placebo: 1411 M/456 F | 50% with T2DM | HFrEF (≤40%) | Empagliflozin 10 mg once daily, added to standard heart failure therapy, follow-up ~16 months |

| McMurray et al., 2019 [8] | RCT, double-blinded, Multinational (410 centers in 20 countries) | 4744 patients (2373 dapagliflozin; 2371 placebo) | Dapa: 66.2 ± 11 years Placebo: 66.5 ± 10.8 years | Dapa: 1809/564 Placebo: 1826/545 | 2065 patients with diabetes at baseline | NYHA class II-IV, LVEF ≤ 40% | Dapagliflozin 10 mg once daily + standard therapy vs. placebo |

| Study (Author, Year) | Hospitalization for Heart Failure | CV Death | Other Outcomes | Adverse Event | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lassen et al., 2024 [25] | HF hospitalization vs. placebo 1 GLT: HR 1.09 (0.79–1.50), p = 0.60 ≥2 GLTs: HR 1.14 (0.83–1.56), p = 0.44 | No GLT: 52/720 1 GLT: 103/1150 ≥2 GLTs: 291/1280 | Dapagliflozin showed consistent benefits vs. placebo across background GLTs: 0 GLTs (HR 0.71), 1 GLT (HR 1.04), and ≥2 GLTs (HR 0.71; p interaction = 0.59). Similar findings were noted for participants with (HR 0.73) and without metformin (HR 0.89; p interaction = 0.22), and with (HR 0.89) and without insulin (HR 0.78; p interaction = 0.45). | No increased risk of serious AEs, discontinuation, or hypoglycemia with dapagliflozin | Dapagliflozin safely reduced CV events and improved symptoms in T2D + HFmrEF/HFpEF, regardless of background GLT. |

| Fu et al., 2023 [26] | NR | NR | Change in LVEF Change from Baseline at 1 Year: Dapagliflozin group: +5.5% (from 30.6% to 36.3%) Placebo group: +2.5% (from 31.3% to 33.7%) LVED volume: −6.0 mL vs. placebo (p < 0.001) LVES volume: −8.1 mL vs. placebo (p < 0.001) LVED diameter: −1.6 mm vs. placebo (p = 0.002) VTI: +0.20 cm vs. placebo (p = 0.036) HbA1c: −0.6% vs. placebo (p < 0.001). | Hypoglycemia: Dapa 1 (3.3%) vs. Placebo 0 Urinary Tract Infection: Dapa 2 (6.7%, females) vs. Placebo 0 Genital Infection: Dapa 1 (3.3%, female) vs. Placebo 0 Volume Depletion: Dapa 1 (3.3%) vs. Placebo 1 (3.3%) | Dapagliflozin resulted in notable improvements in echocardiographic measures of left ventricular remodeling compared with placebo in individuals with T2D and HF with reduced ejection fraction over 1 year. The drug was well-tolerated. |

| Kusunose et al., 2021 [27] | NR | NR | HbA1c Change: A greater decrease was noted in the group receiving glimepiride. Final HbA1c: Canagliflozin: 6.93%; Glimepiride: 6.73% NT-proBNP Change (Primary Outcome): Total Population: Change Ratio (Canagliflozin compared to Glimepiride): 0.93 | Not detailed in sub-analysis; empagliflozin was well tolerated. | Canagliflozin demonstrated a tendency to lower NT-proBNP levels in patients exhibiting significant LV diastolic dysfunction when compared to glimepiride, although the overall study did not achieve its main objective. |

| Szarek et al., 2021 [28] | HR 0.61 (0.45–0.84), p = 0.002 | Rate ratio for total CV events: 0.67 (95% CI, 0.52–0.85) | Days Alive and Out of Hospital (DAOH): RR 1.03 (1.00–1.06), p = 0.027 All-cause death: HR 0.78 (0.54–1.12), p = 0.183 | NR | Sotagliflozin increased DAOH, reduced total hospitalizations (especially HF-related), and reduced days dead in high-risk T2D patients with recent worsening HF. |

| Cosentino et al., 2020 [29] | Pooled Ertugliflozin vs. Placebo: 2.5% (139/5499) vs. 3.6% (99/2747). HR: 0.70 (95% CI, 0.54–0.90); p = 0.006. By Dose: 5 mg vs. Placebo: 2.6% (71/2752) vs. 3.6% (99/2747); HR 0.71 (95% CI, 0.52–0.97). 15 mg vs. Placebo: 2.5% (68/2747) vs. 3.6% (99/2747); HR 0.68 (95% CI, 0.50–0.93). Event Rates: Ertugliflozin 0.73–0.75 vs. Placebo 1.05 per 100 patient-years | Pooled Ertugliflozin vs. Placebo: 8.1% (444/5499) vs. 9.1% (250/2747). Event Rates: Ertugliflozin ~2.34 vs. Placebo 2.66 per 100 patient-years | Total HHF Events: Rate Ratio (RR): 0.70 (95% CI, 0.56–0.87) Total Composite of HHF or CV Death: HR: 0.88 (95% CI, 0.75–1.03) | Major Adverse CV Event (MACE): Ertugliflozin achieved non-inferiority (HR = 0.97) | Among T2DM patients, ertugliflozin decreased the likelihood of experiencing their first HHF as well as the overall rate of HHF and the combination of total HHF with cardiovascular death. |

| de Boer et al., 2020 [30] | NR | Deaths: 2 (One participant in the licogliflozin 10 mg group and one in the placebo group). Both were deemed not related to the study drug. | Change in NT-proBNP at 12 weeks (Geometric Mean Ratio vs. placebo): Licogliflozin 2.5 mg: Ratio 0.78 Licogliflozin 10 mg: Ratio 0.56 Licogliflozin 50 mg: Ratio 0.64 The 10 mg dose showed a statistically significant reduction. Trends towards improvement in glycaemic control, weight, and blood pressure were also observed. | Most Common Adverse Events (AEs): Hypotension, Hypoglycemia, Inadequate diabetes control. Diarrhea: 4.9% in pooled licogliflozin groups (lower than previously reported). Serious AEs: Licogliflozin 2.5 mg: 2 (13.3%) Licogliflozin 10 mg: 2 (12.5%)—Includes one cardiac death Licogliflozin 50 mg: 3 (10.0%) Empagliflozin 25 mg: 5 (16.7%) Placebo: 3 (9.1%) | The use of licogliflozin, which inhibits both SGLT1 and SGLT2, may lower NT-proBNP levels in patients with T2DM and HF. |

| Ejiri et al., 2020 [31] | NR | NR | Change in BNP ratio (12 weeks): Luseogliflozin: Ratio = 0.79 (Percent change: −9.0%; 95% CI: −20.0 to 3.4) Voglibose: Ratio = 0.87 (Percent change: −1.9%; 95% CI: −12.3 to 9.6) Comparison: Ratio of change (Luseogliflozin/Voglibose) = 0.93 (95% CI: 0.78 to 1.10; p = 0.26) | Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE): 0 in both groups. Hypoglycemic adverse events: Luseogliflozin 0 vs. Voglibose 1 (1.2%) (p = 0.49) Urinary Tract Infection: Luseogliflozin 0 vs. Voglibose 1 (1.2%) (p = 0.49) Any Infection: 1 (1.2%) in each group (p = 1.0) Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Luseogliflozin 0 vs. Voglibose 6 (7.3%) (p = 0.013) | T2DM and HFpEF patients starting treatment with luseogliflozin do not lead to a significant decrease in BNP levels after 12 weeks, when compared to voglibose. |

| Griffin et al., 2020 [32] | NR | NR | Natriuresis (FENa—Monotherapy): 1.2 ± 0.7% vs. 0.7 ± 0.4% with placebo Natriuresis (FENa—with Loop Diuretic): 5.8 ± 2.5% vs. 3.9 ± 1.9% with placebo. Change in Blood Volume (at 14 days): −208 mL (IQR: −536 to 153) vs. −14 mL (IQR: −282 to 335) with placebo Change in Plasma Volume (at 14 days): −138 mL (IQR: −379 to 154) vs. +453 mL with placebo | Potassium Excretion: No difference vs. placebo Serum Potassium: No difference vs. placebo eGFR (Creatinine-based): No significant difference in change vs. placebo Symptomatic Hypoglycemia, DKA, GU Infections: 0 | In patients with T2DM and chronic HF, empagliflozin promotes significant natriuresis, whether used alone or with loop diuretics. This leads to decreased blood and plasma volume after 14 days, without causing negative effects on electrolytes, kidney function, or neurohormonal activity. This positive diuretic action may help explain the favorable long-term outcomes in heart failure seen with SGLT2 inhibitors. |

| Packer et al., 2020 [16] | For all populations: 0.69 (0.59–0.81) | 0.92 (0.75–1.12) | Primary composite (CV death or HHF): 19.4% vs. 24.7%, HR 0.75 (0.65–0.86) For Diabetic: 0.72 (0.60–0.87) All-cause death: 13.4% vs. 14.2%, HR 0.92 (0.77–1.10) Renal composite: 1.6% vs. 3.1%, HR 0.50 (0.32–0.77) eGFR decline: −0.55 vs. −2.28 mL/min/1.73m2/year (p < 0.001) KCCQ score: Greater improvement with empagliflozin | Genital infections: More frequent with empagliflozin Hypoglycemia, amputations, fractures: No significant difference Volume depletion, renal events: Similar between groups Discontinuation: 16.3% vs. 18.0% | Empagliflozin significantly decreased the risk of death related to cardiovascular issues and reduced hospital admissions for heart failure in patients with HFrEF, independent of their diabetes status. Additionally, it helped slow the deterioration of kidney function and reduce the risk of serious kidney-related complications. Its safety profile was comparable to that of a placebo, although it was linked to a higher occurrence of genital infections. |

| McMurray et al., 2019 [8] | For the entire population: HR = 0.70 (0.59–0.83) | HR = 0.82 (0.69–0.98) | Primary Composite (Worsening HF or CV Death): For Diabetic: HR = 0.75 (0.63–0.90) | Major Hypoglycemia DAPA: 4/2368 (0.2%) Placebo: 4/2368 (0.2%) Diabetic Ketoacidosis Dapa: 3/2368 (0.1%) Placebo: 0 | Dapagliflozin significantly improves outcomes in HFrEF, lowering hospitalizations and CV death, independent of diabetes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alrasheed, R.R.; Altaf, A.F.; Althurwi, A.H.; Alrodan, S.F.; Asiri, M.H.; Alsaluli, B.A.; Alsurur, M.A.; Alghamdi, K.A.; Alrowaithi, A.A.; Almalki, N.S. Heart Failure Outcomes with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2026, 62, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010069

Alrasheed RR, Altaf AF, Althurwi AH, Alrodan SF, Asiri MH, Alsaluli BA, Alsurur MA, Alghamdi KA, Alrowaithi AA, Almalki NS. Heart Failure Outcomes with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrasheed, Raghad Rasheed, Amenah Fayez Altaf, Abdullah Hameed Althurwi, Shahad Fahad Alrodan, Manal Hussain Asiri, Bushra Abdulrahman Alsaluli, Muath Awadh Alsurur, Khalid Ali Alghamdi, Ahmed Anwer Alrowaithi, and Nariman Safar Almalki. 2026. "Heart Failure Outcomes with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Medicina 62, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010069

APA StyleAlrasheed, R. R., Altaf, A. F., Althurwi, A. H., Alrodan, S. F., Asiri, M. H., Alsaluli, B. A., Alsurur, M. A., Alghamdi, K. A., Alrowaithi, A. A., & Almalki, N. S. (2026). Heart Failure Outcomes with SGLT2 Inhibitors in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina, 62(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010069