Artificial Intelligence Applied to Electrocardiograms Recorded in Sinus Rhythm for Detection and Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

- -

- Population: Adults (≥18 years) with baseline ECG recorded in sinus rhythm (no sustained arrhythmia on the input tracing). Multiple ECGs per patient were allowed.

- -

- Index test/intervention: Any AI or machine learning model (e.g., CNN, DNN…) trained on and applied to ECG data (raw signals or ECG images).

- -

- Comparator: Not mandatory. When present, comparators could include clinical risk scores (e.g., CHARGE-AF), polygenic risk scores, or clinician interpretation.

- -

- Outcomes:

- Detection of paroxysmal AF and/or short-term AF risk prediction (subclinical/latent disease already present; AI-based models could either detect the presence of paroxysmal AF or the short-term onset of known paroxysmal AF (time of AF onset < 1 year from the baseline ECG recording));

- Prediction of long-term new-onset AF (risk stratification for long-term future/new-onset disease; none of the included patients supposedly had AF during baseline ECG recording (time of AF onset > 1 year from the baseline ECG recording));

- Clinical implementation outcomes when AI-ECG was applied prospectively.

- -

- Study design: Retrospective or prospective cohort studies, diagnostic accuracy studies, and interventional/implementation trials.

- -

- Publication: Full-length, peer-reviewed articles in English.

- -

- Time frame: Inception to 16 November 2025.

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

- -

- Case reports, narrative reviews, editorials, conference abstracts.

- -

- Studies including datasets with AF (or other sustained arrhythmia) on the input ECG.

- -

- Studies not using a standard 12-lead ECG for input tracing in the training cohort.

- -

- Animal studies or purely simulated datasets.

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Extraction

- -

- Study characteristics: year, country, setting, design, sample size, inclusion/exclusion criteria, follow-up.

- -

- ECG data: duration, sampling frequency and filters, sinus rhythm and AF definition.

- -

- AI model: architecture (CNN, DNN …), training/validation cohort splits, availability of explainability methods.

- -

- Validation method: internal and/or external validation.

- -

- Reference standard for AF: prior AF diagnosis, AF on other ECGs, AF on long-term monitoring or insertable cardiac monitors.

- -

- AF prediction horizon (if applicable).

- -

- Predictive performance: AUC (AUROC), sensitivity, specificity, calibration metrics.

- -

- Clinical outcomes (if reported): AF-related stroke, mortality, cognitive decline, or AF detection yield in implementation trials.

- -

- Funding sources and potential conflicts of interest.

2.6. Risk of Bias

2.7. Data Synthesis and Analysis

3. Results

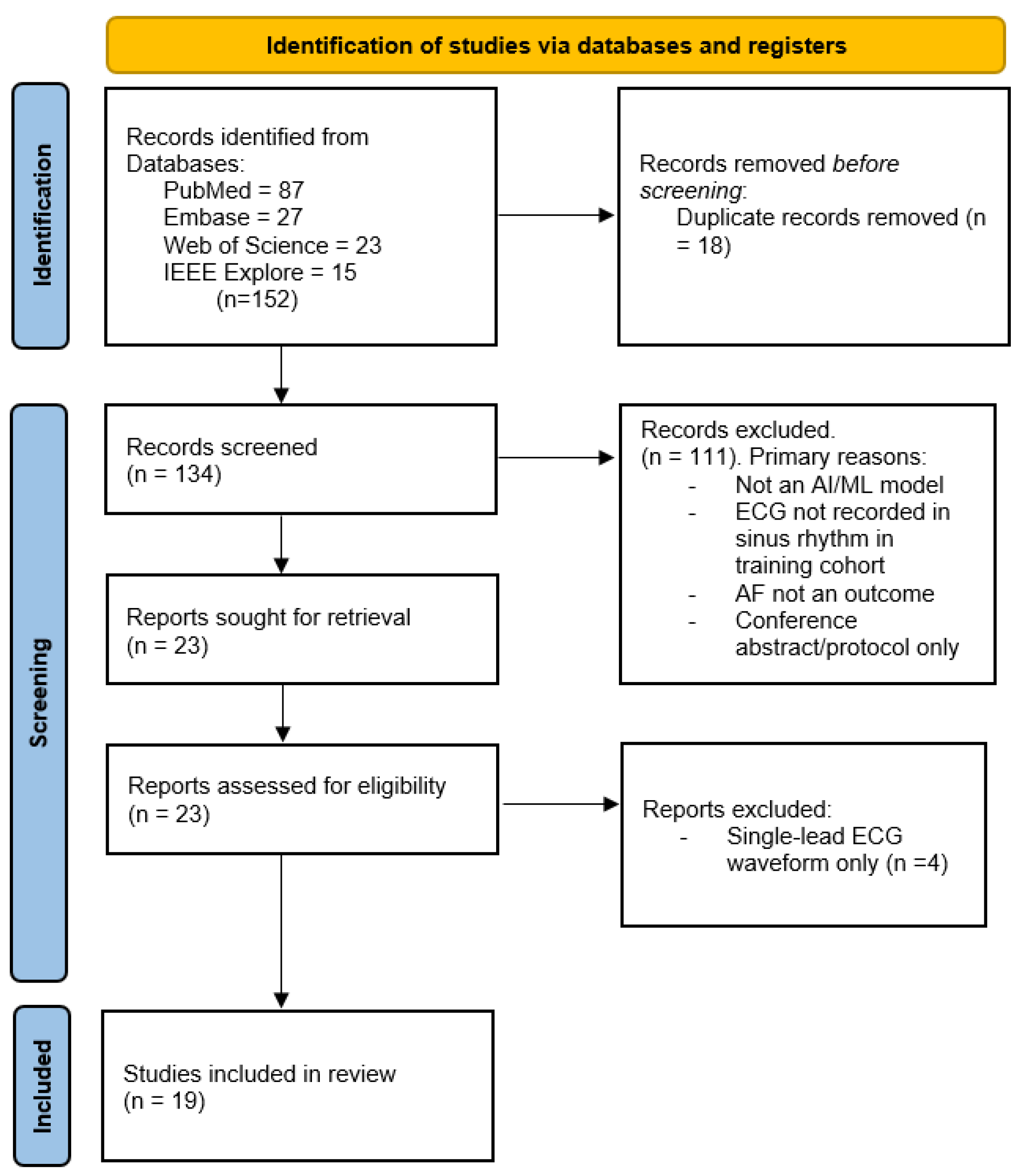

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.2.1. Settings and Patient Populations of the Included Studies

3.2.2. ECG Modalities

3.2.3. AI Model Types

3.2.4. Outcomes and Validation

- -

- -

- -

3.3. Performance of AI Models

3.3.1. Detection of Paroxysmal AF and/or Short-Term Future AF Risk Prediction

- -

- Attia et al., 2019 [12]: CNN achieved AUROC 0.87 for detecting AF from a single sinus rhythm ECG. Model performance improved to ≈0.90 when the ECG was recorded close in time (30 days) to a documented AF episode.

- -

- Baek et al., 2021 [26]: DNN achieved AUROC 0.75–0.79 for identifying paroxysmal AF. The AI-based model focused on P-wave morphology.

- -

- Gruwez et al., 2023 [31]: External validation of the Mayo AI-ECG-AF algorithm in Belgium showed AUROC 0.87 for detection of subclinical AF.

- -

- Hygrell et al., 2023 [28]: CNN was trained on 12-lead ECGs and tested on a single ECG lead device. AI-based model achieved AUROC 0.80 for detecting paroxysmal AF in the age-diverse SAFER cohort but only 0.62 in the age-homogenous STROKESTOP cohorts.

- -

- Aminorroaya et al. [23], 2025: CNN, trained on 12-lead ECG images, accurately detected AF/atrial flutter with AUROC 0.80.

- -

- Jin et al., 2025 [32]: DNN achieved AUROC 0.90 to predict the onset of known paroxysmal AF within one month of a normal sinus rhythm ECG.

- -

- Chang et al., 2025 [24]: CNN model achieved AUROC 0.86 to detect past episodes of AF and AUROC 0.85 to predict future AF events in patients with paroxysmal AF.

- -

- Cai et al., 2020 [25]: DNN, trained on 12-lead ECG images, accurately predicted subclinical AF with AUROC ≈ 0.90 in a small cohort.

- -

- Yuan et al., 2023 [27]: CNN accurately detected paroxysmal AF and predicted its onset within one month, achieving AUROC 0.86, with multiple external validations ranging 0.83–0.93.

- -

- Tarabanis et al., 2025 [30]: CNN + CHARGE-AF clinical score improved paroxysmal AF detection (AUROC 0.89) relative to either ECG-AI (AUROC 0.83) or CHARGE-AF alone.

3.3.2. Prediction of Long-Term New-Onset AF

- -

- Christopoulos et al., 2020 [21]: CNN model predicted AF over 14-year follow-up with AUROC 0.69., measuring up to clinical CHARGE-AF score. Furthermore, combining the AI-based model with CHARGE-AF outperformed both modalities (AUROC 0.72).

- -

- Raghunath et al., 2021 [13]: DNN predicted 1-year new-onset AF with AUROC 0.80–0.85. In all patients who experienced AF-related stroke, the model predicted high risk for new-onset AF in 62% patients.

- -

- Khurshid et al., 2022 [14]: CNN alone achieved AUROC 0.71–0.82 and was comparable to CHARGE-AF. Combination of ECG-AI and clinical risk model improved prediction of new-onset AF (AUROC 0.75–0.84).

- -

- Jabbour et al., 2024 [15]: ECG-AI alone yielded AUC 0.73–0.78; combining ECG, clinical variables, and polygenic score produced AUC ≈ 0.78 and improved model calibration.

- -

- Brant et al., 2025 [16]: Multinational validation (FHS, UKBB, ELSA-Brasil) of a DNN ECG model showed AUROC 0.80–0.82 across heterogeneous populations. The model was complementary to CHARGE-AF (AUROC 0.85).

- -

- Habineza et al., 2023 [33]: CNN-based model, trained and evaluated on a large cohort, achieved AUC 0.85 for predicting new-onset AF in seven years.

3.3.3. Clinical Implementation Studies

- -

- Noseworthy et al., 2022 [17]: AI-guided risk stratification tripled AF detection (10.6% vs. 3.6%) over a median follow-up of 9.9 months in high-risk patients in a pragmatic, real-world trial.

- -

- Weil et al., 2022 [22]: High-risk AI-ECG AF scores predicted cognitive impairment and greater brain infarct burden, suggesting relevance to AF-related target organ damage.

- -

- Choi et al., 2024 [29]: AI applied to sinus rhythm ECG in patients with embolic stroke of unknown source (ESUS) improved selection for prolonged monitoring, achieving high occult AF yield.

3.4. Risk of Bias and Applicability

- -

- Participant selection: Studies usually included retrospective datasets from high-income countries; data from low-resource countries is limited. The majority of studies focused on patients who were at high risk for new-onset AF or those with subclinical AF.

- -

- Predictors: AI-based models were often trained on large cohorts. However, using multiple ECGs per patient was variably reported.

- -

- Outcomes: Sinus rhythm and AF were verified in all studies. AF detection and prediction were assessed across different patient populations. However, several studies included a limited number of ECG records.

- -

- Analysis: Internal validation was performed in most studies; external validation was reported in 11 studies. Calibration and decision-curve reporting were inconsistent. The number of participants with the outcome was limited in several studies due to a small testing cohort and a low prevalence of paroxysmal AF.

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Explainability and ECG Substrate

4.2. Model Discrimination and Comparison with Clinical Risk Scores

4.3. Generalization and Dataset Heterogeneity

4.4. Model Calibration

4.5. AI-ECG Screening

4.6. Limitations of Current Evidence

4.7. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur. Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, D.; Gawalko, M.; Betz, K.; Hendriks, J.M.; Lip, G.Y.H.; Vinter, N.; Guo, Y.; Johnsen, S. Atrial fibrillation: Epidemiology, screening and digital health. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2024, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, P.A.; Abbott, R.D.; Kannel, W.B. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: The Framingham Study. Stroke 1991, 22, 983–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanna, T.; Diener, H.-C.; Passman, R.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Bernstein, R.A.; Morillo, C.A.; Rymer, M.M.; Thijs, V.; Rogers, T.; Beckers, F.; et al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. New Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 2478–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odutayo, A.; Wong, C.X.; Hsiao, A.J.; Hopewell, S.; Altman, D.G.; Emdin, C.A. Atrial fibrillation and risks of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and death: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2016, 354, i4482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennberg, E.; Engdahl, J.; Al-Khalili, F.; Friberg, L.; Frykman, V.; Rosenqvist, M. Mass screening for untreated atrial fibrillation: The STROKESTOP study. Circulation 2015, 131, 2176–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.D.; Atlas, S.J.; Go, A.S.; Lubitz, S.A.; McManus, D.D.; Dolor, R.J.; Chatterjee, R.; Rothberg, M.B.; Rushlow, D.R.; Crosson, L.A.; et al. Effect of Screening for Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation on Stroke Prevention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 84, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.B.; Kühl, J.T.; Pietersen, A.; Graff, C.; Lind, B.; Struijk, J.J.; Olesen, M.S.; Sinner, M.F.; Bachmann, T.N.; Haunsø, S.; et al. P-wave duration and the risk of atrial fibrillation: Results from the Copenhagen ECG Study. Heart Rhythm 2015, 12, 1887–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.B.; Pietersen, A.; Graff, C.; Lind, B.; Struijk, J.J.; Olesen, M.S.; Haunsø, S.; Gerds, T.A.; Ellinor, P.T.; Køber, L.; et al. Risk of atrial fibrillation as a function of the electrocardiographic PR interval: Results from the Copenhagen ECG Study. Heart Rhythm 2013, 10, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siontis, K.C.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Attia, Z.I.; Friedman, P.A. Artificial intelligence-enhanced electrocardiography in cardiovascular disease management. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipollone, P.; Pierucci, N.; Matteucci, A.; Palombi, M.; Laviola, D.; Bruti, R.; Vinciullo, S.; Bernardi, M.; Spadafora, L.; Cersosimo, A.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Cardiac Electrophysiology: A Comprehensive Review. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, Z.I.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Asirvatham, S.J.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Gersh, B.J.; Carter, R.E.; Yao, X.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Erickson, B.J.; et al. An artificial intelligence-enabled ECG algorithm for the identification of patients with atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm: A retrospective analysis of outcome prediction. Lancet 2019, 394, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, S.; Pfeifer, J.M.; Ulloa-Cerna, A.E.; Nemani, A.; Carbonati, T.; Jing, L.; vanMaanen, D.P.; Hartzel, D.N.; Ruhl, J.A.; Lagerman, B.F.; et al. Deep neural networks can predict new-onset atrial fibrillation from the 12-lead ECG and help identify those at risk of AF-related stroke. Circulation 2021, 143, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khurshid, S.; Friedman, S.; Reeder, C.; Di Achille, P.; Diamant, N.; Singh, P.; Harrington, L.X.; Wang, X.; Al-Alusi, M.A.; Sarma, G.; et al. ECG-based deep learning and clinical risk factors to predict atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2022, 145, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabbour, G.; Nolin-Lapalme, A.; Tastet, O.; Corbin, D.; Jordà, P.; Sowa, A.; Delfrate, J.; Busseuil, D.; Hussin, J.G.; Dubé, M.P.; et al. Prediction of incident atrial fibrillation using deep learning, clinical models, and polygenic scores. Eur. Hear. J. 2024, 45, 4920–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brant, L.C.C.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Eromosele, O.B.; Pinto-Filho, M.M.; Barreto, S.M.; Duncan, B.B.; Lin, H. Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation from the ECG in the Community Using Deep Learning: A Multinational Study. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2025, 18, e013734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noseworthy, P.A.; Attia, Z.I.; Behnken, E.M.; Pinto-Filho, M.M.; Barreto, S.M.; Duncan, B.B.; Larson, M.G.; Benjamin, E.J.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Lin, H. Artificial intelligence-guided screening for atrial fibrillation using electrocardiogram during sinus rhythm: A prospective non-randomised interventional trial. Lancet 2022, 400, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ose, B.; Sattar, Z.; Gupta, A.; Toquica, C.; Harvey, C.; Noheria, A. Artificial Intelligence Interpretation of the Electrocardiogram: A State-of-the-Art Review. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2024, 26, 561–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakasis, P.; Theofilis, P.; Sagris, M.; Pamporis, K.; Stachteas, P.; Sidiropoulos, G.; Vlachakis, P.K.; Patoulias, D.; Antoniadis, A.P.; Fragakis, N. Artificial Intelligence in Atrial Fibrillation: From Early Detection to Precision Therapy. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannun, A.Y.; Rajpurkar, P.; Haghpanahi, M.; Tison, G.H.; Bourn, C.; Turakhia, M.P.; Ng, A.Y. Cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection and classification in ambulatory electrocardiograms using a deep neural network. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, G.; Graff-Radford, J.; Lopez, C.L.; Yao, X.; Attia, Z.I.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Petersen, R.C.; Knopman, D.S.; Mielke, M.M.; Kremers, W.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Electrocardiography to Predict Incident Atrial Fibrillation: A Population-Based Study. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2020, 13, e009355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, E.L.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Lopez, C.L.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Friedman, P.A.; Attia, Z.I.; Yao, X.; Siontis, K.C.; Kremers, W.K.; Christopoulos, G.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Electrocardiogram for Atrial Fibrillation Identifies Cognitive Decline Risk and Cerebral Infarcts. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022, 97, 871–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminorroaya, A.; Dhingra, L.S.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Khera, R. Leveraging deep learning for detecting atrial fibrillation and flutter and predicting thromboembolic events from images of 12-lead electrocardiograms in sinus rhythm. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, ehaf784.544. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.C.; Chen, J.S.; Chou, C.C.; Wo, H.T.; Lee, W.C.; Liu, H.T.; Wang, C.C.; Lin, C.H.; et al. Utilizing 12-lead electrocardiogram and machine learning to retrospectively estimate and prospectively predict atrial fibrillation and stroke risk. Comput. Biol. Med. 2025, 188, 109871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Chen, Y.; Guo, J.; Han, B.; Shi, Y.; Ji, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, G.; Luo, J. Accurate detection of atrial fibrillation from 12-lead ECG using deep neural network. Comput. Biol. Med. 2020, 116, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, Y.S.; Lee, S.C.; Choi, W.; Kim, D.H. A new deep learning algorithm of 12-lead electrocardiogram for identifying atrial fibrillation during sinus rhythm. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, N.; Duffy, G.; Dhruva, S.S.; Oesterle, A.; Pellegrini, C.N.; Theurer, J.; Vali, M.; Heidenreich, P.A.; Keyhani, S.; Ouyang, D. Deep Learning of Electrocardiograms in Sinus Rhythm from US Veterans to Predict Atrial Fibrillation. JAMA Cardiol. 2023, 8, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hygrell, T.; Viberg, F.; Dahlberg, E.; Charlton, P.H.; Kemp Gudmundsdottir, K.; Mant, J.; Hörnlund, J.L.; Svennberg, E. An artificial intelligence-based model for prediction of atrial fibrillation from single-lead sinus rhythm electrocardiograms facilitating screening. Europace 2023, 25, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Cho, M.S.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Oh, I.Y.; Cho, Y.; Lee, J.H. Artificial intelligence predicts undiagnosed atrial fibrillation in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source using sinus rhythm electrocardiograms. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabanis, C.; Koesmahargyo, V.; Tachmatzidis, D.; Sousonis, V.; Bakogiannis, C.; Ronan, R.; Bernstein, S.A.; Barbhaiya, C.; Park, D.S.; Holmes, D.S.; et al. Artificial intelligence–enabled sinus electrocardiograms for the detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation benchmarked against the CHARGE-AF score. Eur. Heart J.—Digit. Health 2025, 6, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruwez, H.; Barthels, M.; Haemers, P.; Verbrugge, F.H.; Dhont, S.; Meekers, E.; Wouters, F.; Nuyens, D.; Pison, L.; Vandervoort, P.; et al. Detecting Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation from an Electrocardiogram in Sinus Rhythm: External Validation of the AI Approach. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9 Pt 3, 1771–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Ko, B.; Chang, W.; Choi, K.H.; Choi, K.H.; Lee, K.H. Explainable paroxysmal atrial fibrillation diagnosis using an artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiogram. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2025, 40, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habineza, T.; Ribeiro, A.H.; Gedon, D.; Behar, J.A.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Schön, T.B. End-to-end risk prediction of atrial fibrillation from the 12-Lead ECG by deep neural networks. J. Electrocardiol. 2023, 81, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, N.M.S.; Kleber, A.; Narayan, S.M.; Ciaccio, E.J.; Doessel, O.; Bernus, O.; Berenfeld, O.; Callans, D.; Fedorov, V.; Hummel, J.; et al. Atrial fibrillation nomenclature, definitions, and mechanisms: Position paper from the international Working Group of the Signal Summit. Heart Rhythm 2025, 22, 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalife, J. Mechanisms of persistent atrial fibrillation. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2014, 29, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonov, P.G. P-wave morphology: Underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Ann. Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2012, 17, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, J.W.; Wang, N.; Nelson, K.P.; Connelly, S.; Deo, R.; Rodondi, N.; Schelbert, E.B.; Garcia, M.E.; Phillips, C.L.; Shlipak, M.G.; et al. Electrocardiographic PR interval and adverse outcomes in older adults: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2013, 6, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magnani, J.W.; Johnson, V.M.; Sullivan, L.M.; Gorodeski, E.Z.; Schnabel, R.B.; Lubitz, S.A.; Levy, D.; Ellinor, P.T.; Benjamin, E.J. P Wave Duration and Risk of Longitudinal Atrial Fibrillation Risk in Persons ≥60 Years Old (from the Framingham Heart Study). Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 107, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbrugge, F.H.; Reddy, Y.N.V.; Attia, Z.I.; Friedman, P.A.; Noseworthy, P.A.; Lopez-Jimenez, F.; Kapa, S.; Borlaug, B.A. Detection of left atrial myopathy using artificial intelligence-enabled electrocardiography. Circ. Hear. Fail. 2022, 15, e008176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhang, M.J.; Wang, W.; Zhuang, Z.; He, R.; Ji, Y.; Knutson, K.A.; Norby, F.L.; Alonso, A.; Soliman, E.Z. Multimodal data integration to predict atrial fibrillation. Eur. Heart J.—Digit. Health 2025, 6, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüscher, T.F.; Wenzl, F.A.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Friedman, P.A.; Antoniades, C. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular medicine: Clinical applications. Eur. Hear. J. 2024, 45, 4291–4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, G.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Dhiman, P.; Riley, R.D.; Beam, A.L.; Van Calster, B.; Ghassemi, M.; Liu, X.; Reitsma, J.B.; van Smeden, M.; et al. TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning methods. BMJ 2024, 385, e078378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, M.V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Hedlin, H.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Garcia, A.; Ferris, T.; Balasubramanian, V.; Russo, A.M.; Rajmane, A.; Cheung, L.; et al. Apple Heart Study Investigators. Large-Scale Assessment of a Smartwatch to Identify Atrial Fibrillation. New Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mrak, Z.; Naji, F.H.; Dinevski, D. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Electrocardiograms Recorded in Sinus Rhythm for Detection and Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scoping Review. Medicina 2026, 62, 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010199

Mrak Z, Naji FH, Dinevski D. Artificial Intelligence Applied to Electrocardiograms Recorded in Sinus Rhythm for Detection and Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scoping Review. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010199

Chicago/Turabian StyleMrak, Ziga, Franjo Husam Naji, and Dejan Dinevski. 2026. "Artificial Intelligence Applied to Electrocardiograms Recorded in Sinus Rhythm for Detection and Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scoping Review" Medicina 62, no. 1: 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010199

APA StyleMrak, Z., Naji, F. H., & Dinevski, D. (2026). Artificial Intelligence Applied to Electrocardiograms Recorded in Sinus Rhythm for Detection and Prediction of Atrial Fibrillation: A Scoping Review. Medicina, 62(1), 199. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010199