An Early Warning Marker in Acute Respiratory Failure: The Prognostic Significance of the PaCO2–ETCO2 Gap During Noninvasive Ventilation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Study Protocol and Data Collection

2.4. Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scala, R.; Heunks, L. Highlights in acute respiratory failure. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2018, 27, 180008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, S.P.; Sinuff, T.; Burns, K.E.A.; Muscedere, J.; Kutsogiannis, J.; Mehta, S.; Cook, D.J.; Ayas, N.; Adhikari, N.K.; Hand, L.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in the acute care setting. CMAJ 2011, 183, E195–E214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.; González-Díaz, G.; Ferrer, M.; Martinez-Quintana, M.E.; Lopez-Martinez, A.; Llamas, N.; Alcazar, M.; Torres, A. Non-invasive ventilation in community-acquired pneumonia and severe acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2012, 38, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodali, B.S. Capnography outside the operating rooms. Anesthesiology 2013, 118, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuraya, M.; Douno, E.; Iwata, W.; Takaba, A.; Hadama, K.; Kawamura, N.; Maezawa, T.; Iwamoto, K.; Yoshino, Y.; Yoshida, K. Accuracy evaluation of mainstream and sidestream end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring during noninvasive ventilation: A randomized crossover trial (MASCAT-NIV trial). J. Intensive Care 2022, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunn, J.F.; Hill, D.W. Respiratory dead space and arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide tension difference in anaesthetised man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1960, 15, 383–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razi, E.; Moosavi, G.A.; Omidi, K.; Khakpour Saebi, A.; Razi, A. Correlation of end-tidal carbon dioxide with arterial carbon dioxide in mechanically ventilated patients. Arch. Trauma Res. 2012, 1, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thacker, J.; Stroud, A.; Carge, M.; Baldwin, C.; Shahait, A.D.; Tyburski, J.; Dolman, H.; Tarras, S. Utility of arterial CO2–end-tidal CO2 gap as a mortality indicator in the surgical ICU. Am. J. Surg. 2023, 225, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askrog, V. Changes in (a–A)CO2 difference and pulmonary artery pressure in anaesthetised man. J. Appl. Physiol. 1966, 21, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- İşat, G.; Öztürk, T.; Onur, Ö.; Özdemir, S.; Akoğlu, E.; Akyıl, T.; Okur, H. Comparison of the arterial PaCO2 values and ETCO2 values measured with sidestream capnography in patients with a prediagnosis of COPD exacerbation. Avicenna J. Med. 2023, 13, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D. Predicting the outcome of noninvasive ventilation in acute type 2 respiratory failure. Indian J. Crit. Care Med. 2024, 28, S51–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shetty, A.; Sparenberg, S.; Adams, K.; Selvedran, S.; Tang, B.; Hanna, K.; Iredell, J. Arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide tension difference (CO2 gap) as a prognostic marker for adverse outcomes in emergency department patients presenting with suspected sepsis. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2018, 30, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalrazik, F.S.; Elghonemi, M.O. Assessment of gradient between partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide and end-tidal carbon dioxide in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Egypt. J. Bronchol. 2019, 13, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defilippis, V.; D’Antini, D.; Cinnella, G.; Dambrosio, M.; Schiraldi, F.; Procacci, V. End-tidal arterial CO2 partial pressure gradient in patients with severe hypercapnia undergoing noninvasive ventilation. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2013, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Jewell, E.; Engoren, M.; Maile, M. Difference between arterial and end-tidal carbon dioxide and adverse events after non-cardiac surgery: A historical cohort study. Can. J. Anaesth. 2022, 69, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.S.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, T.Y.; Lee, J.M.; Park, H.; Lee, H.; Yang, N.R.; Baik, S.M. Utility of arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide gradient as a severity index in critical care. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2025, 369, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masoumi, G.; Noyani, A.; Dehghani, A.; Afrasiabi, A.; Kianmehr, N. Investigation of the relationship between end-tidal carbon dioxide and partial arterial carbon dioxide pressure in patients with respiratory distress. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2020, 34, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardesai, N.; Hibberd, O.; Price, J.; Ercole, A.; Barnard, E. Agreement between arterial and end-tidal carbon dioxide in adult patients admitted with serious traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upchurch, C.; Wessman, B.; Roberts, B.; Fuller, B. Arterial to end-tidal carbon dioxide gap and its characterization in mechanically ventilated adults in the emergency department. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 73, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentola, R.; Hästbacka, J.; Heinonen, E.; Rosenberg, P.H.; Häggblom, T.; Skrifvars, M.B. Estimation of arterial carbon dioxide based on end-tidal gas pressure and oxygen saturation. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.; Brandan, L.; Telias, I. Monitoring patients with acute respiratory failure during non-invasive respiratory support to minimize harm and identify treatment failure. Crit. Care 2025, 29, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, P.; Tonelli, R.; Torregiani, C.; Baratella, E.; Confalonieri, M.; Battaglini, D.; Marchioni, A.; Confalonieri, P.; Clini, E.; Salton, F.; et al. Different methods to improve the monitoring of noninvasive respiratory support of patients with severe pneumonia/ARDS due to COVID-19: An update. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Woman | 17 (50.0) |

| Male | 17 (50.0) |

| Age * | 73.26 ± 10.07 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure * | 132.20 ± 28.12 |

| Diastolic TA * | 74.38 ± 15.11 |

| Pulse * | 106.88 ± 25.70 |

| Respiratory Rate * | 30.08 ± 5.90 |

| Temperature * | 36.46 ± 0.29 |

| End Tidal Measurement 1 * | 34.76 ± 12.51 |

| pH 1. Measurement * | 7.35 ± 0.10 |

| PaCO2 Measurement 1 * | 44.29 ± 16.49 |

| Saturation 02 1st Measurement * | 87.00 ± 14.43 |

| PaO2 Measurement 1 * | 80.47 ± 25.78 |

| Lactate Measurement 1 * | 3.09 ± 2.33 |

| HCO3 1st Measurement * | 22.91 ± 4.86 |

| Difference 1. Measurement * | 9.52 ± 9.43 |

| End Tidal Measurement 2 * | 33.64 ± 11.41 |

| pH 2. Measurement * | 7.36 ± 0.12 |

| PaCO2 Measurement 2 * | 43.04 ± 13.12 |

| Saturation 02 2nd Measurement * | 92.65 ± 10.23 |

| PaO2 Measurement 2 * | 94.86 ± 37.33 |

| Lactate Measurement 2 * | 2.87 ± 2.37 |

| HCO3 2nd Measurement * | 23.07 ± 5.24 |

| Difference 2. Measurement * | 9.40 ± 7.21 |

| Delta Difference * | 0.12 ± 8.12 |

| Emergency room discharge, n (%) | |

| Yes | 7 (20.6) |

| No | 27 (79.4) |

| Type of respiratory failure | |

| Type 1 | 24 (70.6) |

| Type 2 | 10 (29.4) |

| Intubation | |

| Yes | 9 (26.5) |

| No | 25 (73.5) |

| Intensive Care Unit Admission | |

| Yes | 20 (58.8) |

| No | 14 (41.2) |

| Mortality | |

| None | 24 (70.6) |

| Exitus | 10 (29.4) |

| Intubation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | There | p | |

| Age | 73.00 ± 10.87 76.00 (51.00–92.00) | 74.00 ± 7.96 74.00 (62.00–86.00) | 0.860 + |

| Systolic Blood Pressure | 136.48 ± 29.94 138.00 (84.00–192.00) | 120.33 ± 18.94 113.00 (95.00–155.00) | 0.171 * |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 75.72 ± 16.30 76.00 (48.00–112.00) | 70.66 ± 11.10 70.00 (57.00–90.00) | 0.423 * |

| Pulse | 105.56 ± 25.73 110.00 (58.00–158.00) | 110.55 ± 26.78 108.00 (65.00–160.00) | 0.696 * |

| Respiratory Rate | 30.44 ± 6.10 30.00 (20.00–44.00) | 29.11 ± 5.51 28.00 (21.00–38.00) | 0.595 * |

| Temperature | 36.41 ± 0.30 36.40 (36.00–37.20) | 36.61 ± 0.22 36.50 (36.40–37.10) | 0.013 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 1 | 35.44 ± 10.81 36.00 (20.00–53.00) | 32.88 ± 17.03 30.00 (11.00–58.00) | 0.639 * |

| pH 1. Measurement | 7.35 ± 0.10 7.38 (7.08–7.53) | 7.32 ± 0.11 7.30 (7.22–7.50) | 0.329 * |

| PaCO2 Measurement 1 | 46.06 ± 16.53 41.00 (24.20–85.00) | 39.38 ± 16.27 38.50 (20.20–63.00) | 0.274 + |

| Saturation 02 1st Measurement | 86.99 ± 15.51 93.00 (38.20–98.60) | 87.04 ± 11.71 93.30 (70.30–98.00) | 0.922 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 1 | 81.67 ± 24.73 75.20 (48.50–140.00) | 77.12 ± 29.83 66.70 (47.00–130.00) | 0.401 * |

| Lactate Measurement 1 | 2.76 ± 2.46 1.70 (0.50–8.90) | 4.01 ± 1.72 4.70 (0.80–5.50) | 0.069 + |

| HCO3 1st Measurement | 24.15 ± 4.51 24.20 (15.00–34.80) | 19.47 ± 4.28 18.90 (15.40–29.00) | 0.012 * |

| Difference 1. Measurement | 10.62 ± 10.75 7.10 (0.20–46.00) | 6.50 ± 2.42 6.60 (2.20–9.20) | 0.711 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 2 | 35.16 ± 11.22 32.00 (18.00–60.00) | 29.44 ± 11.52 27.00 (11.00–51.00) | 0.218 * |

| pH 2. Measurement | 7.39 ± 0.11 7.40 (7.10–7.72) | 7.21 ± 0.08 7.25 (7.21–7.48) | 0.006 + |

| PaCO2 Measurement 2 | 42.73 ± 13.22 41.50 (26.70–72.50) | 43.91 ± 13.56 39.80 (22.80–67.50) | 0.725 + |

| Saturation 02 2nd Measurement | 94.48 ± 9.72 96.00 (60.40–120.00) | 87.56 ± 10.43 91.00 (71.00–99.00) | 0.075 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 2 | 100.74 ± 40.35 91.50 (48.00–223.00) | 78.54 ± 21.40 72.50 (56.90–120.00) | 0.105 + |

| Lactate Measurement 2 | 2.30 ± 2.13 1.40 (0.40–8.50) | 4.45 ± 2.42 5.80 (1.00–6.80) | 0.037 + |

| HCO3 2nd Measurement | 24.48 ± 4.67 25.00 (14.70–34.00) | 19.15 ± 4.93 18.10 (14.20–29.40) | 0.014 * |

| Difference 2. Measurement | 7.57 ± 6.89 5.00 (0.00–25.00) | 14.46 ± 5.70 12.00 (9.00–26.00) | 0.007 + |

| Delta Difference | −3.04 ± 6.93 −1.00 ((−22.50)–4.00) | 7.96 ± 5.24 6.90 (2.80–17.00) | 0.001 + |

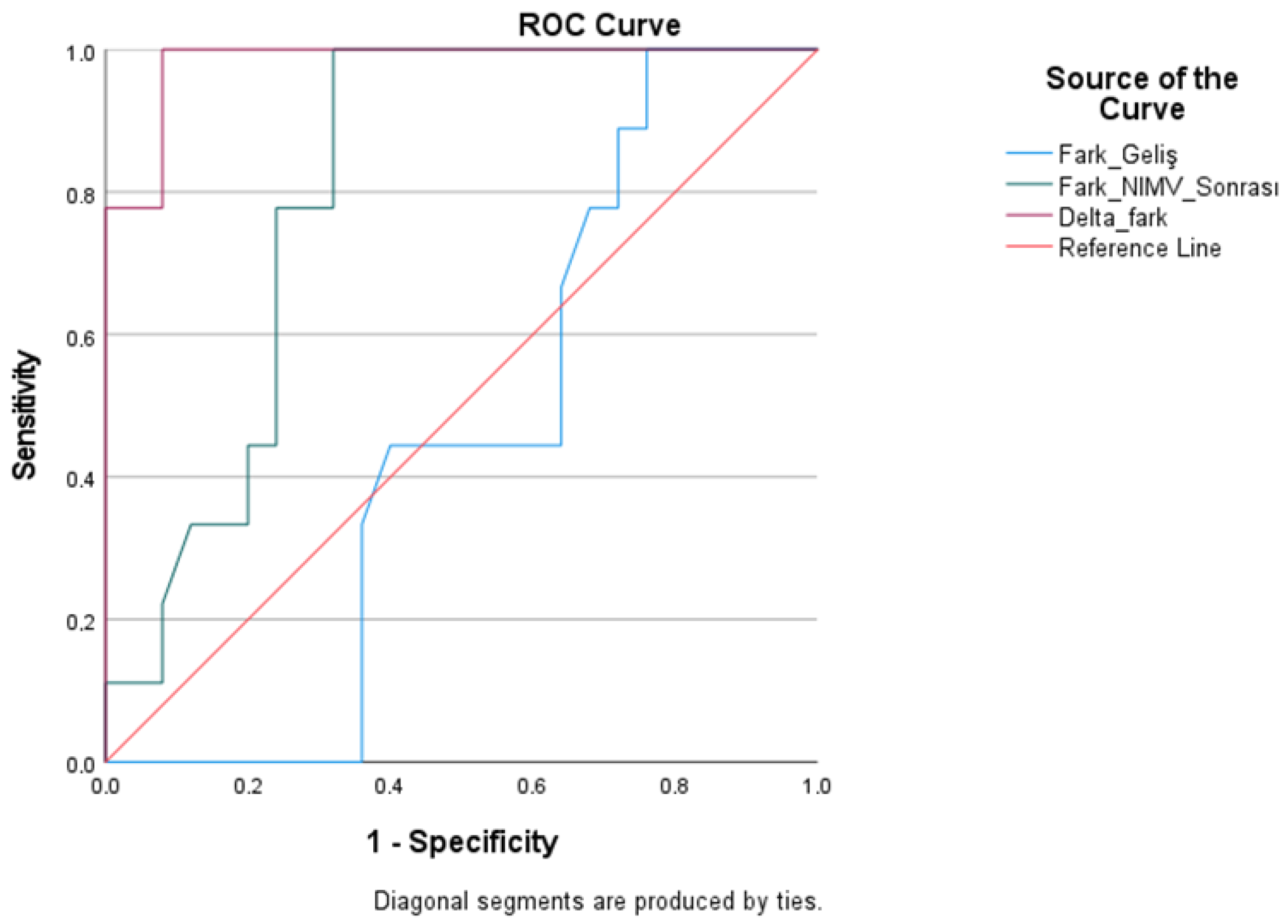

| Test Result Variables | Cutoff | AUC | Std. Error | Youden Index J | p | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment difference | >6.30 | 0.458 | 0.098 | −0.09 | 0.711 | 0.265 | 0.650 | 55.60 | 36.00 |

| Post-Treatment Difference | >10.90 | 0.807 | 0.073 | 0.53 | 0.007 | 0.663 | 0.950 | 77.80 | 76.00 |

| Delta Difference | >2.90 | 0.982 | 0.018 | 0.80 | 0.001 | 0.947 | 0.1000 | 88.90 | 92.00 |

| Intensive Care Unit Admission | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Age | 73.78 ± 10.15 75.50 (51.00–92.00) | 72.90 ± 10.26 75.00 (51.00–86.00) | 0.944 * |

| Systolic blood pressure | 140.42 ± 27.95 139.00 (100.00–192.00) | 126.45 ± 27.47 117.00 (84.00–188.00) | 0.151 * |

| Diastolic TA | 79.50 ± 17.10 79.00 (48.00–112.00) | 70.80 ± 12.79 67.00 (53.00–98.00) | 0.096 * |

| Pulse | 99.14 ± 25.56 9.00 (58.00–140.00) | 112.30 ± 25.00 114.00 (65.00–160.00) | 0.208 * |

| Respiratory Rate | 30.57 ± 6.68 30.00 (20.00–44.00) | 29.75 ± 5.43 29.50 (20.00–41.00) | 0.832 * |

| Temperature | 36.35 ± 0.28 36.40 (36.00–37.20) | 36.54 ± 0.28 36.50 (36.00–37.10) | 0.010 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 1 | 36.00 ± 9.93 39.00 (22.00–51.00) | 33.90 ± 14.23 30.00 (11.00–58.00) | 0.661 * |

| pH 1. Measurement | 7.35 ± 0.09 7.36 (7.08–7.48) | 7.34 ± 0.11 7.35 (7.19–7.53) | 0.806 * |

| PaCO2 Measurement 1 | 47.65 ± 17.33 40.60 (31.00–85.00) | 41.94 ± 15.89 39.25 (20.20–71.70) | 0.302 + |

| Saturation 02 1st Measurement | 88.80 ± 10.72 93.40 (62.00–98.00) | 85.75 ± 16.69 92.85 (38.20–98.60) | 0.972 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 1 | 73.70 ± 24.26 68.55 (47.00–140.00) | 85.20 ± 26.35 79.80 (49.10–130.00) | 0.208 + |

| Lactate Measurement 1 | 2.42 ± 2.11 1.60 (0.50–8.20) | 3.56 ± 2.42 3.45 (0.60–8.90) | 0.183 + |

| HCO3 1st Measurement | 23.84 ± 3.76 24.10 (18.20–30.00) | 22.27 ± 5.50 20.70 (15.00–34.80) | 0.294 * |

| Difference 1. Measurement | 11.65 ± 13.11 7.70 (0.20–46.00) | 8.04 ± 5.58 7.00 (0.20–21.00) | 0.713 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 2 | 36.28 ± 11.17 34.50 (21.00–60.00) | 31.80 ± 11.49 28.00 (11.00–54.00) | 0.213 * |

| pH 2. Measurement | 7.36 ± 0.09 7.37 (7.10–7.48) | 7.36 ± 0.13 7.34 (7.18–7.72) | 0.687 * |

| PaCO2 Measurement 2 | 44.06 ± 12.54 42.20 (28.20–72.50) | 42.33 ± 13.78 38.90 (22.80–69.70) | 0.575 * |

| Saturation 02 2nd Measurement | 95.91 ± 10.66 98.20 (71.00–120.00) | 90.36 ± 9.53 93.65 (60.40–99.00) | 0.020 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 2 | 112.90 ± 47.21 102.00 (52.10–223.00) | 82.24 ± 22.10 81.25 (48.00–139.00) | 0.025 * |

| Lactate Measurement 2 | 2.17 ± 1.94 1.30 (0.40–6.60) | 3.36 ± 2.57 2.25 (0.60–8.50) | 0.278 + |

| HCO3 2nd Measurement | 24.02 ± 4.30 24.85 (17.50–29.50) | 22.41 ± 5.82 22.10 (14.20–34.00) | 0.344 * |

| Difference 2. Measurement | 7.77 ± 8.43 3.50 (0.00–26.00) | 10.53 ± 6.19 10.70 (0.70–25.00) | 0.077 + |

| Delta Difference | −3.87 ± 10.26 −1.60 ((−22.50)–17.00) | 2.49 ± 4.89 2.25 ((−6.30)–16.00) | 0.016 + |

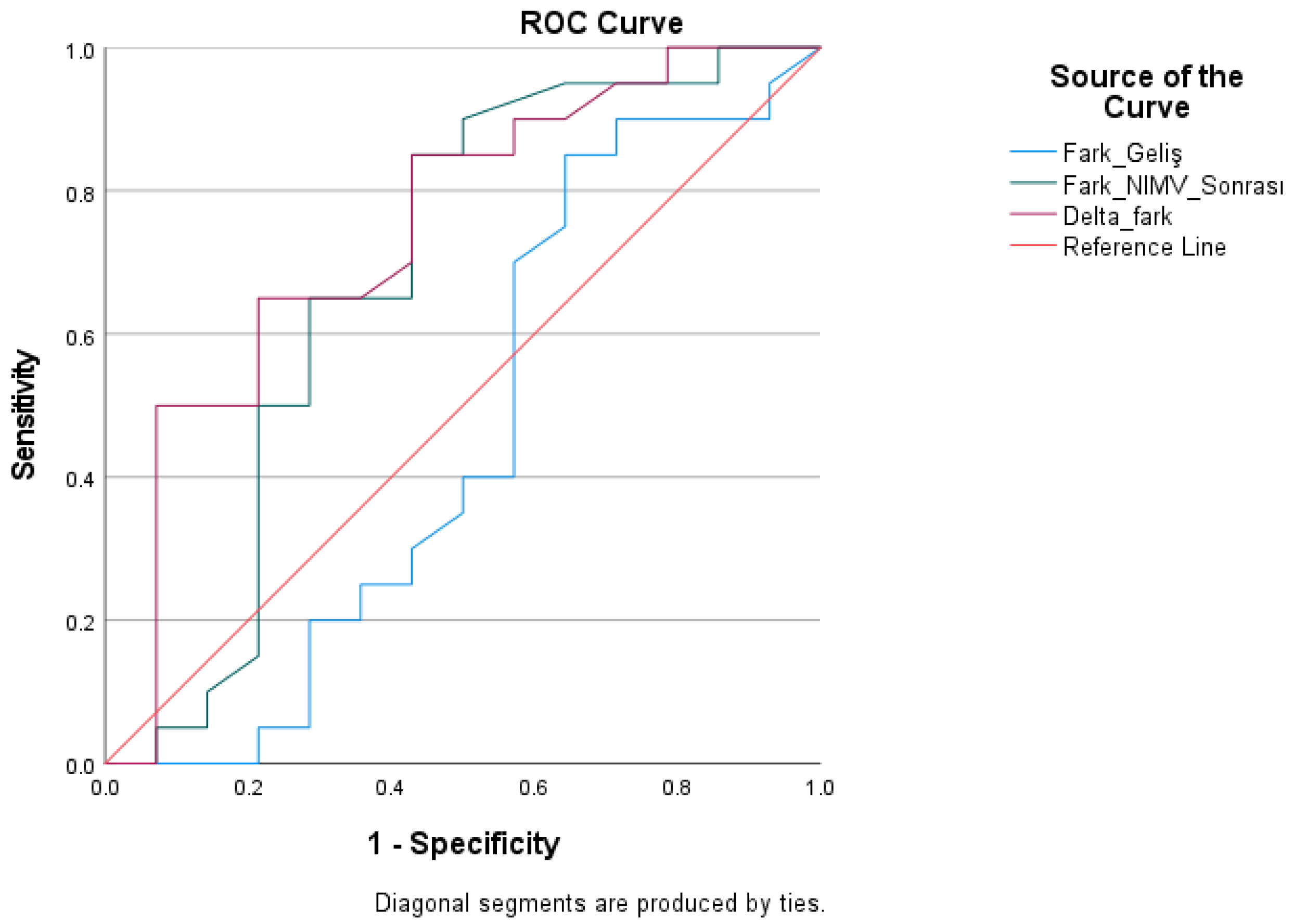

| Test Result Variables | Cutoff | AUC | Std. Error | Youden Index J | p | Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval | Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment difference | >7.05 | 0.462 | 0.111 | −0.13 | 0.713 | 0.245 | 0.680 | 45.00 | 42.90 |

| Post-Treatment Difference | >8.75 | 0.680 | 0.104 | 0.36 | 0.077 | 0.476 | 0.884 | 65.00 | 71.40 |

| Delta Difference | >0.65 | 0.746 | 0.089 | 0.38 | 0.016 | 0.572 | 0.921 | 60.00 | 78.60 |

| Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Age | 72.97 ± 10.84 75.50 (51.00–92.00) | 74.40 ± 8.35 73.50 (61.00–86.00) | 0.970 + |

| Systolic blood pressure | 136.12 ± 30.55 135.50 (84.00–192.00) | 122.80 ± 19.37 117.00 (95.00–155.00) | 0.316 * |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure | 74.58 ± 16.40 72.00 (48.00–112.00) | 73.90 ± 12.21 76.00 (57.00–90.00) | 0.895 * |

| Pulse | 100.70 ± 21.55 101.00 (58.00–140.00) | 121.70 ± 29.82 122.50 (65.00–160.00) | 0.033 * |

| Respiratory Rate | 29.83 ± 6.39 29.00 (20.00–44.00) | 30.70 ± 4.73 30.00 (21.00–38.00) | 0.446 * |

| Temperature | 36.41 ± 0.30 36.40 (36.00–37.20) | 36.58 ± 0.25 36.50 (36.20–37.10) | 0.040 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 1 | 34.70 ± 11.87 37.50 (11.00–53.00) | 34.90 ± 14.63 32.00 (14.00–58.00) | 0.925 * |

| pH 1. Measurement | 7.35 ± 0.10 7.37 (7.08–7.53) | 7.33 ± 0.10 7.33 (7.22–7.50) | 0.416 * |

| PaCO2 Measurement 1 | 45.49 ± 16.78 40.60 (20.20–85.00) | 41.41 ± 16.27 39.25 (20.60–67.60) | 0.472 * |

| Saturation 02 1st Measurement | 85.69 ± 15.98 92.70 (38.20–98.00) | 90.16 ± 9.73 93.65 (72.00–98.60) | 0.438 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 1 | 78.60 ± 24.81 73.40 (48.50–140.00) | 84.94 ± 28.86 79.85 (47.00–130.00) | 0.650 + |

| Lactate Measurement 1 | 2.94 ± 2.47 2.00 (0.50–8.90) | 3.46 ± 2.03 3.85 (0.60–5.50) | 0.438 + |

| HCO3 1st Measurement | 23.92 ± 4.21 24.60 (15.00–30.90) | 20.50 ± 5.65 20.10 (15.40–34.80) | 0.038 + |

| Difference 1. Measurement | 10.78 ± 10.68 7.65 (00.20–46.00) | 6.51 ± 4.46 6.30 (0.20–16.60) | 0.290 + |

| End Tidal Measurement 2 | 35.04 ± 11.22 31.00 (18.00–60.00) | 30.30 ± 11.75 27.50 (11.00–54.00) | 0.233 * |

| pH 2. Measurement | 7.37 ± 0.12 7.37 (7.10–7.72) | 7.31 ± 0.09 7.27 (7.21–7.48) | 0.140 * |

| PaCO2 Measurement 2 | 43.06 ± 13.03 40.75 (26.70–72.50) | 43.00 ± 14.04 40.90 (22.80–69.70) | 0.985 * |

| Saturation 02 2nd Measurement | 93.87 ± 10.45 96.00 (60.40–120.00) | 89.70 ± 9.54 92.00 (71.00–99.00) | 0.167 + |

| PaO2 Measurement 2 | 100.52 ± 41.53 90.75 (48.00–223.00) | 81.27 ± 20.29 74.05 (56.90–120.00) | 0.140 + |

| Lactate Measurement 2 | 2.56 ± 2.32 1.40 (0.40–8.50) | 3.63 ± 2.44 3.90 (0.60–6.20) | 0.316 + |

| HCO3 2nd Measurement | 24.15 ± 4.76 25.05 (14.70–29.50) | 20.48 ± 5.67 20.85 (14.20–34.00) | 0.033 + |

| Difference 2. Measurement | 8.02 ± 7.07 5.50 (0.00–25.00) | 12.70 ± 6.75 11.90 (3.60–26.00) | 0.054 + |

| Delta Difference | −2.76 ± 7.42 −0.50 ((−22.50)–8.50) | 6.19 ± 6.15 4.75 ((−1.00)–17.00) | 0.001 + |

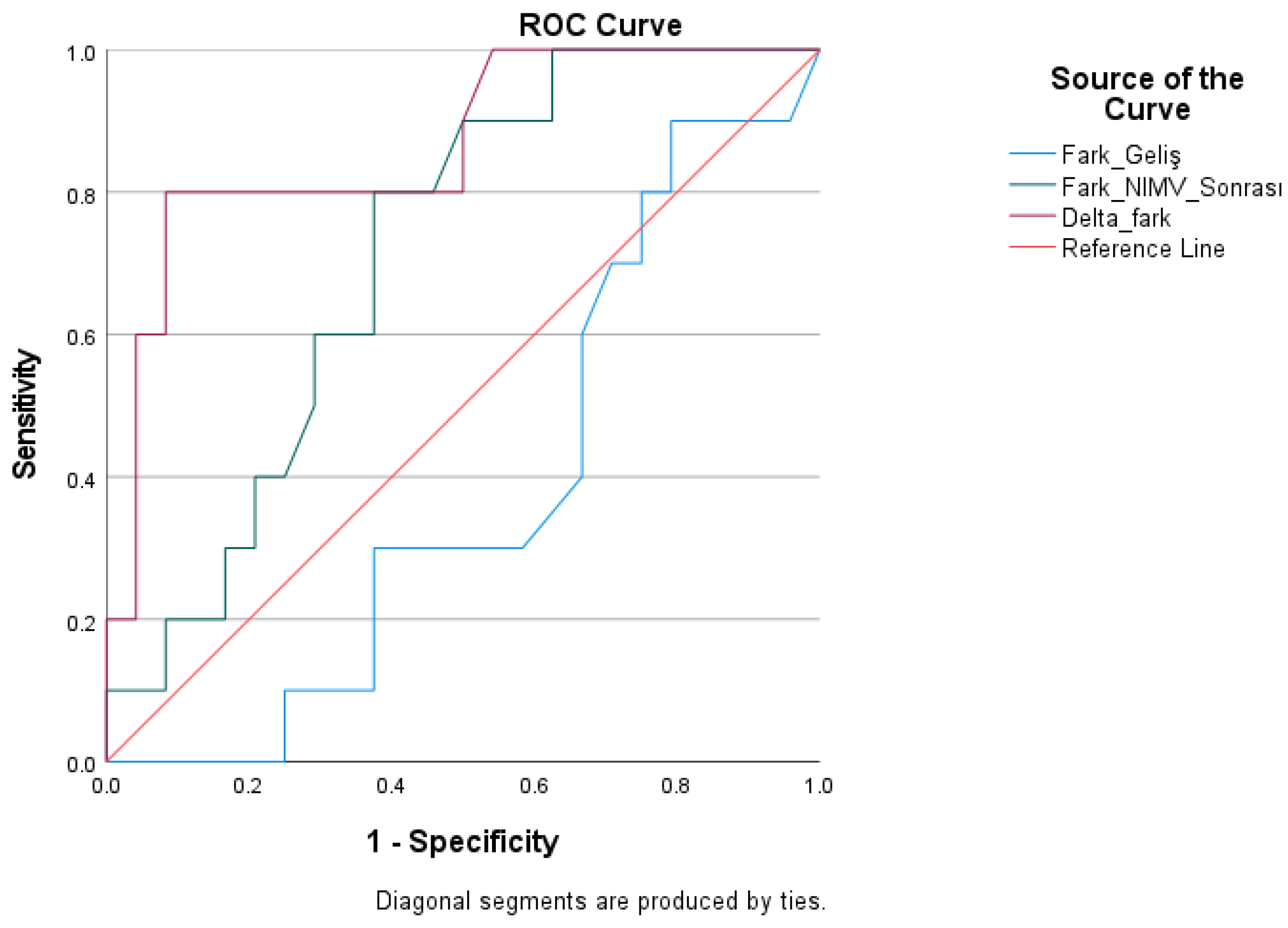

| Test Result Variables | Cutoff | AUC | Std. Error | Youden Index J | p | Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval | Asymptotic 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment difference | >6.80 | 0.383 | 0.099 | −0.27 | 0.290 | 0.190 | 0.577 | 40.00 | 33.30 |

| Post-Treatment Difference | >8.75 | 0.713 | 0.088 | 0.42 | 0.054 | 0.540 | 0.885 | 80.00 | 62.50 |

| Delta Difference | >2.90 | 0.865 | 0.072 | 0.71 | 0.001 | 0.724 | 1000 | 80.00 | 91.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kırık, S.; Efgan, M.G.; Bora, E.S.; Tavşanoğlu, U.; Öz, H.Ö.; Acar, B.; Yıldızlı, S. An Early Warning Marker in Acute Respiratory Failure: The Prognostic Significance of the PaCO2–ETCO2 Gap During Noninvasive Ventilation. Medicina 2026, 62, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010197

Kırık S, Efgan MG, Bora ES, Tavşanoğlu U, Öz HÖ, Acar B, Yıldızlı S. An Early Warning Marker in Acute Respiratory Failure: The Prognostic Significance of the PaCO2–ETCO2 Gap During Noninvasive Ventilation. Medicina. 2026; 62(1):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010197

Chicago/Turabian StyleKırık, Süleyman, Mehmet Göktuğ Efgan, Ejder Saylav Bora, Uğur Tavşanoğlu, Hüseyin Özkan Öz, Burak Acar, and Sedat Yıldızlı. 2026. "An Early Warning Marker in Acute Respiratory Failure: The Prognostic Significance of the PaCO2–ETCO2 Gap During Noninvasive Ventilation" Medicina 62, no. 1: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010197

APA StyleKırık, S., Efgan, M. G., Bora, E. S., Tavşanoğlu, U., Öz, H. Ö., Acar, B., & Yıldızlı, S. (2026). An Early Warning Marker in Acute Respiratory Failure: The Prognostic Significance of the PaCO2–ETCO2 Gap During Noninvasive Ventilation. Medicina, 62(1), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina62010197