Biological Effects of Music Therapy in End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Explored the biological or physiological effects of music therapy in patients at the end of life;

- Provided practical indications for designing music therapy interventions;

- Met the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome criteria defined by the PICOS framework.

3. Results

3.1. Musicological Aspects of Clinical Relevance

3.2. Importance of Individual Preferences

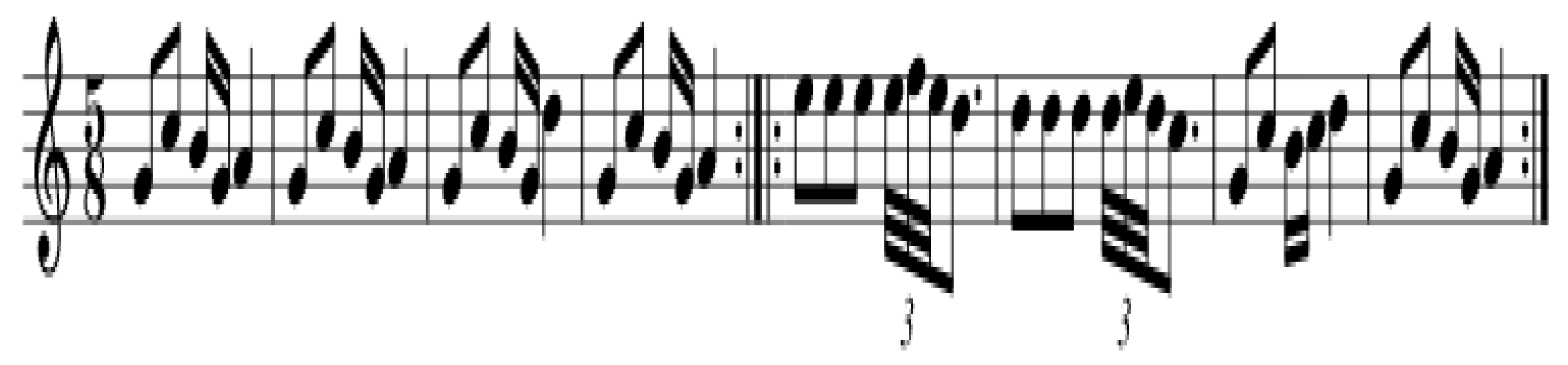

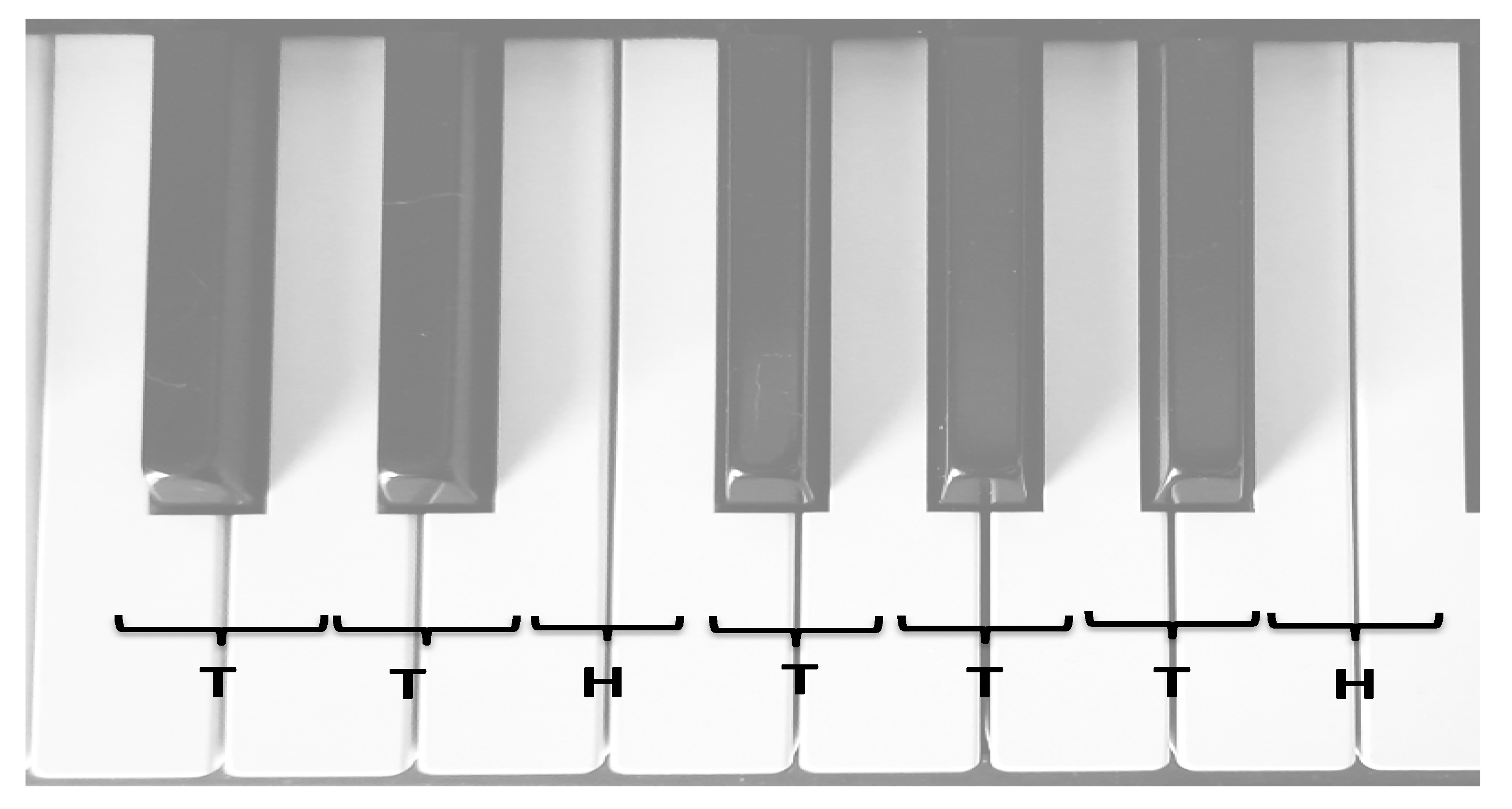

3.3. Rhythmic and Temporal Considerations

3.4. Harmonic Structure and Emotional Impact

3.5. Influence of Musical Training on Therapeutic Response

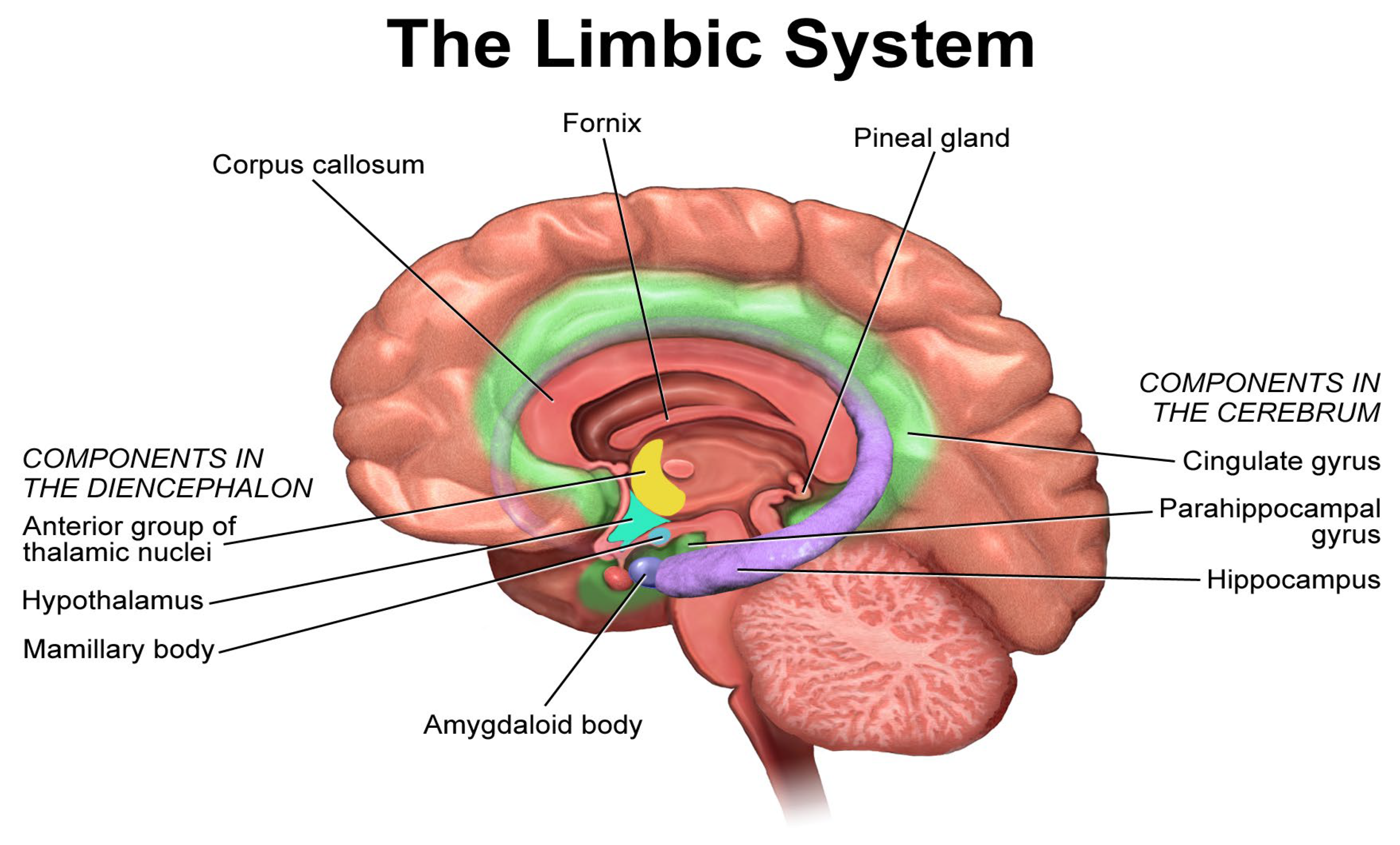

3.6. Neuroanatomy of Musical Perception

3.7. Physiological Effects of Music Therapy

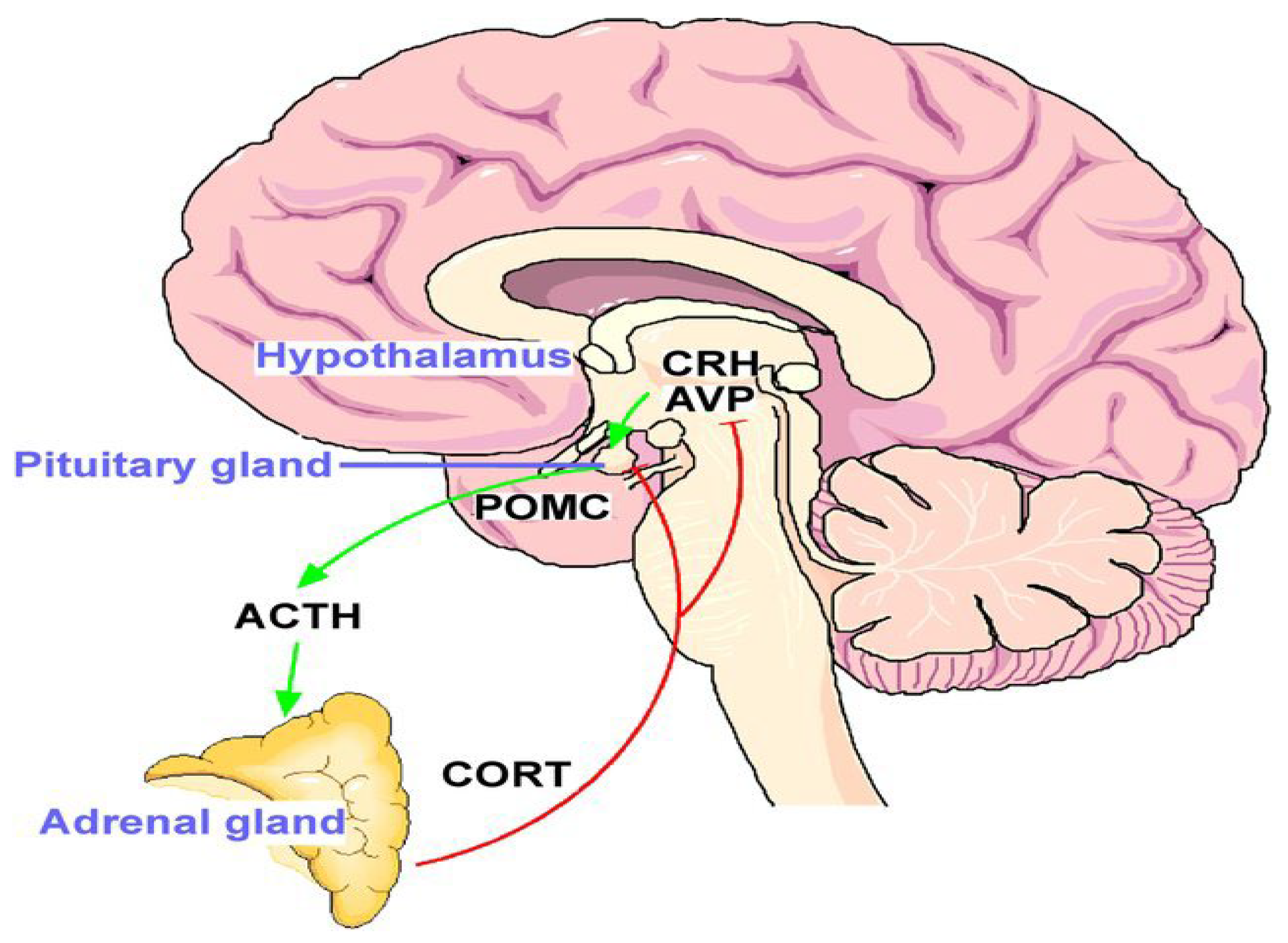

3.8. Psychoneuroimmunological Effects in Cancer Patients

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.2. Limits

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Artificial Intelligence Use

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Köhler, F.; Martin, Z.S.; Hertrampf, R.S.; Gäbel, C.; Kessler, J.; Ditzen, B.; Warth, M. Music Therapy in the Psychosocial Treatment of Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C.; Magill, L.; Teague, A. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 8, CD006911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bissonnette, J.; Dumont, E.; Pinard, A.M.; Landry, M.; Rainville, P.; Ogez, D. Hypnosis and music interventions for anxiety, pain, sleep and well-being in palliative care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 13, e503–e514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yang, W.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Ding, J.; Ding, G. The Effectiveness of Music Therapy for Terminally Ill Patients: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2019, 57, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huda, N.; Banda, K.J.; Liu, A.I.; Huang, T.W. Effects of Music Therapy on Spiritual Well-Being among Patients with Advanced Cancer in Palliative Care: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2023, 39, 151481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warth, M.; Koehler, F.; Brehmen, M.; Weber, M.; Bardenheuer, H.J.; Ditzen, B.; Kessler, J. “Song of Life”: Results of a multicenter randomized trial on the effects of biographical music therapy in palliative care. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 1126–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.; McConnell, T.; Clarke, M.; Kirkwood, J.; Hughes, N.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Regan, J.; McKeown, M.; McGrillen, K.; Reid, J. A critical realist evaluation of a music therapy intervention in palliative care. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottaccioli, F.; Carosella, A.; Cardone, R.; Mambelli, M.; Cemin, M.; D’Errico, M.M.; Ponzio, E.; Bottaccioli, A.G.; Minelli, A. Brief training of psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology-based meditation (PNEIMED) reduces stress symptom ratings and improves control on salivary cortisol secretion under basal and stimulated conditions. Explore 2014, 10, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, G.V.M.C.; Wanigabadu, L.U.; Vidanagama, B.; Samaranayaka, T.S.P.; Jeewandara, J.M.K.C. “Adjunctive Effects of a Short Session of Music on Pain, Low-mood and Anxiety Modulation among Cancer Patients”—A Randomized Crossover Clinical Trial. Indian J. Palliat. Care 2019, 25, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrell, B.R.; Paice, J.A. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Nursing, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, W.; Rosland, J.H.; von Hofacker, S.; Hunskår, I.; Bruvik, F. Patient’s and health care provider’s perspectives on music therapy in palliative care—An integrative review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düzgün, G.; Karadakovan, A. Effect of Music on Pain in Cancer Patients in Palliative Care Service: A Randomized Controlled Study. Omega 2024, 88, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinheiro Hammuod, S.F.; Gonzalez Santos, F.; da Costa Fonseca, L.; Kakuta, E.; Verão Brito, R.; Silva Souza, K.; Loreti, E.H. Music therapy in modulating pain in palliative care patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Music Ther. 2025, 39, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, K.; McConnell, T.; Roulston, A.; Potvin, N.; Ghiglieri, C.; Gadde, I.; Anderson, M.; Kirkwood, J.; Thomas, D.; Roche, L.; et al. Music therapy for supporting informal carers of adults with life-threatening illness pre- and post-bereavement; a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrary, J.M.; Altenmüller, E.; Kretschmer, C.; Scholz, D.S. Association of Music Interventions with Health-Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e223236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh-Wu, S.F.; Kauffman, M.A.; Anglade, D.; Shamsaldeen, F.; Ahn, S.; Downs, C.A. Effectiveness of different music interventions on managing symptoms in cancer survivors: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2021, 52, 101968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosokawa, M.; Ito, M.; Kyota, A.; Hirai, K.; Yamakawa, M.; Miyashita, M. Non-pharmacological interventions for cancer-related fatigue in terminal cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2022, 11, 3382–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prieto-Crespo, V.; Arevalo-Buitrago, P.; Olivares-Luque, E.; García-Arcos, A.; López-Soto, P.J. Impact of Spiritual Support Interventions on the Quality of Life of Patients Who Receive Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 1906–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Yin, B.; Chen, Z.; Peng, X. “Song of Life”: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Biographical Music Therapy in Palliative Care by the EMW-TOPSIS Method. Processes 2022, 10, 1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements-Cortés, A.; Yip, J.J.Y.; Klinck, S. Music Therapy and Music-Based Interventions in Oncology and End-of-Life Care. In Music and Music Therapy Interventions in Clinical Practice: A Textbook for Music Therapy Professionals, Clinicians and Researchers; Raglio, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 305–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daquilema, J.F.C.; Vintimilla, M.G.S.; Ocampo, T.M.S.; López, D.X.C.; Espinoza, M.F.L.; Guadalupe, L.J.S. Utility of Aromatherapy and Music Therapy in Palliative Care: A Review of the Literature. Rev. Gest. Soc. Ambient. 2024, 18, e010294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perusinghe, M.; Chen, K.Y.; McDermott, B. Evidence-Based Management of Depression in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ho, M.H.; Wang, T.; Cheung, D.S.T.; Lin, C.C. Effectiveness of Dyadic Advance Care Planning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, e869–e889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Tan, Y.; Fu, B.; Qiu, H. Effects of hospice care on quality of life and negative emotions in patients with advanced tumor: A protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2020, 99, e20784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baethge, C.; Goldbeck-Wood, S.; Mertens, S. SANRA—A scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir-Behghadami, M.; Janati, A. Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) Design as a Framework to Formulate Eligibility Criteria in Systematic Reviews. Emerg. Med. J. 2020, 37, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosch, T.; Wigram, T.; Holck, U.; Ridder, H.; Scholtz, J.; Voigt, M.; Schumacher, K.; Calvet, C.; Abrams, B.; Baker, F. Microanalysis in Music Therapy: Methods, Techniques and Applications for Clinicians, Researchers, Educators and Students; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 978-1-84310-469-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, R.; Planas, J.; Escude, N.; Mercade, J.; Farriols, C. EEG-based analysis of the emotional effect of music therapy on palliative care cancer patients. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitin, D.J.; Grahn, J.A.; London, J. The Psychology of Music: Rhythm and Movement. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2018, 69, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, S.; Fancourt, D. The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: A systematic review. Progress Brain Res. 2018, 237, 173–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, M.; Politi, P.; Barale, F.; Enzo, E. Neurophysiology and neurobiology of the musical experience. Funct. Neurol. 2006, 21, 187–191. [Google Scholar]

- Särkämö, T.; Tervaniemi, M.; Laitinen, S.; Numminen, A.; Kurki, M.; Johnson, J.K.; Rantanen, P. Cognitive, emotional, and social benefits of regular musical activities in early dementia: Randomized controlled study. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.G.; Lai, K.T.; Tan, S.B.; Sulaiman, A.H.; Zainal, N.Z. The Effect of 5 Minutes of Mindful Breathing to the Perception of Distress and Physiological Responses in Palliative Care Cancer Patients: A Randomized Controlled Study. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C. Music therapy for end-of-life care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, CD007169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, C.H.; Honig, T.J. Health outcomes of a series of bonny method of guided imagery and music sessions: A systematic review. J. Music Ther. 2017, 54, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blausen.com staff. Limbic system. Sagittal section of the brain showing the components of the limbic system. English labels. WikiJournal Med. 2014, 1, 10. Available online: https://anatomytool.org/content/blausen-0614-limbic-system-english-labels (accessed on 9 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, C.; Sproston, M.; Wilkinson, K.; Willis, D.; Milner, A.; Grocke, D.; Wheeler, G. Effect of self-selected music on adults’ anxiety and subjective experiences during initial radiotherapy treatment: A randomised controlled trial and qualitative research. J. Med. Imaging Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 56, 473–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madsen, J.; Margulis, E.H.; Simchy-Gross, R.; Parra, L.C. Music synchronizes brainwaves across listeners with strong effects of repetition, familiarity and training. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preissler, P.; Kordovan, S.; Ullrich, A.; Bokemeyer, C.; Oechsle, K. Favored subjects and psychosocial needs in music therapy in terminally ill cancer patients: A content analysis. BMC Palliat. Care 2016, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murgatroyd, C.; Spengler, D. Epigenetics of early child development. Front Psychiatry 2011, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorasowharid, P. The Use of Music as a Legacy Intervention in Palliative Care: A Scoping Review. Master’s Thesis, Chula ETD, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Eizaguirre, M.; Vergara-Moragues, E. Music Therapy Interventions in Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Care 2021, 36, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaguini, F.; Stoltz, T. A Scoping Review on the Effects of Music Therapy in the Field of Education. Educ. Real. 2024, 49, e133214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, M. Music therapy in dementia and end-of-life care: A report from Italy. Approaches Interdiscip. J. Music Ther. 2020, 12, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.; McAllister, M.; Mulvogue, J. Choirs in end-of-life care: A thematic literature review. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2022, 28, 348–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, F.; Kessler, J.; Stoffel, M.; Weber, M.; Bardenheuer, H.J.; Ditzen, B.; Warth, M. Psychoneuroendocrinological effects of music therapy versus mindfulness in palliative care: Results from the ‘Song of Life’ randomized controlled trial. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 30, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingley, C.; Ruckdeschel, A.; Kotula, K.; Lekhak, N. Implementation and outcomes of complementary therapies in hospice care: An integrative review. Palliat. Care Soc. Pract. 2021, 15, 26323524211051753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, K.J.; Ulrich, A.M.; Larsen, B.E.; Phelps, C.M.; Siska, M.J.; Bigelow, M.L.; Dockter, T.J.; Wood, C.; Walton, M.P.; Stelpflug, A.J.; et al. Music Therapy Intervention to Reduce Caregiver Distress at End of Life: A Feasibility Study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2023, 65, e417–e423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srolovitz, M.; Borgwardt, J.; Burkart, M.; Clements-Cortes, A.; Czamanski-Cohen, J.; Guzman, M.O.; Hicks, M.G.; Kaimal, G.; Lederman, L.; Potash, J.S.; et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Music Therapy and Art Therapy. J. Palliat. Med. 2022, 25, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri-Ezbarami, Z.; Jafaraghaee, F.; Sighlani, A.K.; Mousavi, S.K. Core components of end-of-life care in nursing education programs: A scoping review. BMC Palliat. Care 2024, 23, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.S.; Wang, C.; Ward, K.E.; Hume, A.L. Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Hospice and Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, 781–794.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodie, F.; Anna, K.; Ursula, W. Effectiveness of music therapy, aromatherapy, and massage therapy on patients in palliative care with end-of-life needs: A systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2025, 69, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciğerci, Y.; Kısacık, Ö.G.; Özyürek, P.; Çevik, C. Nursing music intervention: A systematic mapping study. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2019, 35, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbrello, M.; Sorrenti, T.; Mistraletti, G.; Formenti, P.; Chiumello, D.; Terzoni, S. Music therapy reduces stress and anxiety in critically ill patients: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Minerva Anestesiol. 2019, 85, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, T.; Scott, D.; Porter, S. Music therapy for end-of-life care: An updated systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 877–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadwalader, A.; Orellano, S.; Tanguay, C.; Roshan, R. The Effects of a Single Session of Music Therapy on the Agitated Behaviors of Patients Receiving Hospice Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Lo Cascio, A.; Adile, C.; Ferrera, P.; Casuccio, A. Maddalena Opioid Switching Score in patients with cancer pain. Pain 2023, 164, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacchini, F.; Mancin, S.; Cangelosi, G.; Palomares, S.M.; Caggianelli, G.; Gravante, F.; Petrelli, F. The role of artificial intelligence in diabetic retinopathy screening in type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. J. Diabetes Complicat. 2025, 39, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollo, M.; Terzoni, S.; Ferrara, P.; Destrebecq, A.; Bonetti, L. Nursing students’ attitudes towards nutritional care of older people: A multicentre cross-sectional survey incorporating a pre post design. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 78, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Ferrera, P.; Lo Cascio, A.; Casuccio, A. Pain Catastrophizing in Cancer Patients. Cancers 2024, 16, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sguanci, M.; Palomares, S.M.; Cangelosi, G.; Petrelli, F.; Sandri, E.; Ferrara, G.; Mancin, S. Artificial Intelligence in the Management of Malnutrition in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, S.; Adile, C.; Ferrera, P.; Grassi, Y.; Cascio, A.L.; Casuccio, A. Conversion ratios for opioid switching: A pragmatic study. Support. Care Cancer 2022, 31, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancin, S.; Cangelosi, G.; Matteucci, S.; Palomares, S.M.; Parozzi, M.; Sandri, E.; Sguanci, M.; Piredda, M. The Role of Vitamin D in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Implications for Graft-versus-Host Disease—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potvin, N.; Hicks, M.; Kronk, R. Music Therapy and Nursing Cotreatment in Integrative Hospice and Palliative Care. J. Hosp. Palliat. Nurs. 2021, 23, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.S.; Baxter, K.; Lally, K.M. Music Intervention as a Tool in Improving Patient Experience in Palliative Care. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2019, 36, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, L.M.; Lagman, R.; Rybicki, L. Outcomes of Music Therapy Interventions on Symptom Management in Palliative Medicine Patients. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estell, M.H.; Whitford, K.J.; Ulrich, A.M.; Larsen, B.E.; Wood, C.; Bigelow, M.L.; Dockter, T.J.; Schoonover, K.L.; Stelpflug, A.J.; Strand, J.J.; et al. Music Therapy Intervention to Reduce Symptom Burden in Hospice Patients: A Descriptive Study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2025, 42, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Terzoni, S.; Vita, A.D.; Ferrara, P.; Sacchini, F.; Cangelosi, G.; Mancin, S.; Petrelli, F.; Lopane, D.; Milani, A.; Parozzi, M.; et al. Biological Effects of Music Therapy in End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091690

Terzoni S, Vita AD, Ferrara P, Sacchini F, Cangelosi G, Mancin S, Petrelli F, Lopane D, Milani A, Parozzi M, et al. Biological Effects of Music Therapy in End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091690

Chicago/Turabian StyleTerzoni, Stefano, Antonino De Vita, Paolo Ferrara, Francesco Sacchini, Giovanni Cangelosi, Stefano Mancin, Fabio Petrelli, Diego Lopane, Alessandra Milani, Mauro Parozzi, and et al. 2025. "Biological Effects of Music Therapy in End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091690

APA StyleTerzoni, S., Vita, A. D., Ferrara, P., Sacchini, F., Cangelosi, G., Mancin, S., Petrelli, F., Lopane, D., Milani, A., Parozzi, M., & Lusignani, M. (2025). Biological Effects of Music Therapy in End-of-Life Care: A Narrative Review. Medicina, 61(9), 1690. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091690