Evaluating Quality of Life in Surgically Treated IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional and Social Impacts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

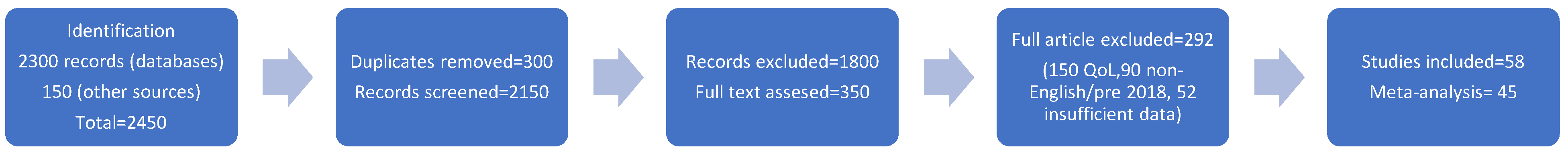

- (1)

- Identification: 2300 records identified via database searches (PubMed: 900, Scopus: 1100, Cochrane Library: 300); 150 additional records from reference lists and grey literature.

- (2)

- Screening: 2450 records screened after duplicates were removed (300 duplicates); 1800 excluded based on title/abstract (non-surgical focus, non-IBD populations).

- (3)

- Eligibility: 650 full-text articles assessed; 592 excluded (300 lacked QoL outcomes, 200 were non-English or pre-2018, 92 had insufficient data).

- (4)

- Included: 58 studies included in qualitative synthesis; 45 included in quantitative meta-analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Surgical Types and Their Impact on QoL

3.3. Surgical Psychological Effects

3.4. Long-Term QoL Outcomes

3.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

3.6. Grading of the Quality of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Physical Health and Surgical Outcomes

4.2. Mental and Emotional Health and Well-Being

4.3. Social Influence and Social Reintegration

4.4. How Is Post Surgical Support Strengthening QoL?

4.5. Beyond the First 10 Years After Diagnosis

4.6. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.7. Limitations of the Studies

4.8. Strengths of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flynn, S.; Eisenstein, S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Presentation and Diagnosis. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 99, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehkamp, J.; Götz, M.; Herrlinger, K.; Steurer, W.; Stange, E.F. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Critical Discussion of Etiology, Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Therapy. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2016, 113, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsenkühn, T.; Sackmann, M.; Göke, B. Chronisch entzündliche Darmerkrankungen—Kritische Diskussion von Atiologie, Pathogenese, Diagnostik und Therapie [Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD)—Critical discussion of etiology, pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapy]. Radiologe 2003, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, R.S.; Baxter, N.N. Quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease after surgery. World J. Surg. 1998, 22, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockburn, E.; Kamal, S.; Chan, A.; Rao, V.; Liu, T.; Huang, J.Y.; Segal, J.P. Crohn’s disease: An update. Clin. Med. 2023, 23, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geldof, J.; Iqbal, N.; LeBlanc, J.F.; Anandabaskaran, S.; Sawyer, R.; Buskens, C.; Bemelman, W.; Gecse, K.; Lundby, L.; Lightner, A.L.; et al. Classifying perianal fistulising Crohn’s disease: An expert consensus to guide decision-making in daily practice and clinical trials. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, A.; Sparrow, M.P. Perianal Crohn’s disease: Still more questions than answers. World J. Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 4260–4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bock, E.; Filipe, M.D.; Meij, V.; Oldenburg, B.; van Schaik, F.D.M.; Bastian, O.W.; Fidder, H.F.; Vriens, M.R.; Richir, M.C. Quality of life in patients with IBD during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021, 8, e000670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, V.; Pingel, J.; Søfelt, H.L.; Hikmat, Z.; Johansson, M.; Pedersen, V.S.; Bertelsen, B.; Carlsson, A.; Lindh, M.; Svavarsdóttir, E.; et al. Sex and gender in inflammatory bowel disease outcomes and research. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 9, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, V.; Liljensøe, A.; Gregersen, L.; Darbani, B.; Halldorsson, T.I.; Heitmann, B.L. Food Is Medicine: Diet Assessment Tools in Adult Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research. Nutrients 2025, 17, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Yao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; Meng, Q.; Ji, J.; Yu, Z.; Chen, X. Fecal microbiota transplantation: Application scenarios, efficacy prediction, and factors impacting donor-recipient interplay. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1556827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, F.; Morace, C.; Impalà, G.; Viola, A.; Lo Gullo, A.; Cinquegrani, M.; Fries, W.; Sardella, A.; Scolaro, M.; Basile, G.; et al. Quality of Life (QoL) in Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: How Much Better with Biological Drugs? J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keung, C.; Nguyen, T.C.; Lim, R.; Gerstenmaier, A.; Sievert, W.; Moore, G.T. Local fistula injection of allogeneic human amnion epithelial cells is safe and well tolerated in patients with refractory complex perianal Crohn’s disease: A phase I open label study with long-term follow up. EBioMedicine 2023, 98, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraes, L.C.; Holubar, S.D.; Lipman, J.M.; Hull, T.L.; Lightner, A.L.; Lavryk, O.A.; Kanters, A.E.; Steele, S.R. Redo Continent Ileostomy in Patients With IBD: Valuable Lessons Learned Over 25 Years. Dis. Colon Rectum 2023, 66, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adegbola, S.O.; Dibley, L.; Sahnan, K.; Wade, T.; Verjee, A.; Sawyer, R.; Mannick, S.; McCluskey, D.; Yassin, N.; Phillips, R.K.S.; et al. Burden of disease and adaptation to life in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistula: A qualitative exploration. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, C.; Athavale, A.; Abilash, V.; Hantsbarger, G.; Geransar, P.; Lee, K.; Milicevic, S.; Perovic, M.; Raven, L.; Sajak-Szczerba, M.; et al. Multi-national observational study to assess quality of life and treatment preferences in patients with Crohn’s perianal fistulas. World J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 15, 2537–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.C.Y.; Rotondi, G.; Roso, M.; Avanzini, P.; Gandullia, P.; Arrigo, S.; Mattioli, G. Quality of life after colectomy and ileo-jpouch-anal anastomosis in paediatric patients with ulcerative colitis. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2024, 40, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Q.E.B.; Tripp, D.A.; Geirc, M.; Gnat, L.; Moayyedi, P.; Beyak, M. Psychosocial factors associated with j-pouch surgery for patients with IBD: A scoping review. Qual. Life Res. 2023, 32, 3309–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, E.L.; Herfarth, H.H.; Sandler, R.S.; Chen, W.; Jaeger, E.; Nguyen, V.M.; Robb, A.R.; Kappelman, M.D.; Martin, C.F.; Long, M.D. Pouch-Related Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, 1218–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkar, R.; Graff, L.A.; Bharadwaj, S.; Lopez, R.; Shen, B. Psychological Factors in Irritable Pouch Syndrome and Other Pouch Disorders. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2815–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnafisah, K.; Alsaleem, H.N.; Aldakheel, F.N.; Alrashidi, A.B.; Alayid, R.A.; Almuhayzi, H.N.; Alrebdi, Y.M. Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease at King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Qassim Region. Cureus 2023, 15, e44895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramuzzo, M.; De Carlo, C.; Arrigo, S.; Pavanello, P.M.; Canaletti, C.; Giudici, F.; Agrusti, A.; Martelossi, S.; Di Leo, G.; Barbi, E. Parental Psychological Factors and Quality of Life of Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casellas, F.; Barreiro de Acosta, M.; Iglesias, M.; Robles, V.; Nos, P.; Aguas, M.; Riestra, S.; de Francisco, R.; Papo, M.; Borruel, N. Mucosal healing restores normal health and quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 24, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinicke, J.A. Ileal Pouch Complications. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 99, 1185–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eaton, J.; Hatch, Q.M. Surgical Emergencies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 104, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhakta, A.; Tafen, M.; Glotzer, O.; Ata, A.; Chismark, A.D.; Valerian, B.T.; Stain, S.C.; Lee, E.C. Increased Incidence of Surgical Site Infection in IBD Patients. Dis. Colon Rectum 2016, 59, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegretti, J.R.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Damas, O.M.; Eisenstein, S.; Greywoode, R.; Minar, P.; Singh, S.; Harmon, S.; Lisansky, E.; Malone-King, M.; et al. Challenges in IBD Research 2024: Pragmatic Clinical Research. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30 (Suppl. 2), S55–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, K.; Yamazaki, H.; Nagahori, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Omori, T.; Mikami, Y.; Fujii, T.; Shinzaki, S.; Saruta, M.; Matsuura, M.; et al. Association of ulcerative colitis symptom severity and proctocolectomy with multidimensional patient-reported outcomes: A cross-sectional study. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triantafyllakis, I.; Saridi, M.; Toska, A.; Albani, E.N.; Togas, C.; Christodoulou, D.K.; Katsanos, K.H. Surgical Intervention in Patients with Idiopathic Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Perianal Disease. Pol. Merkur. Lek. Organ Pol. Tow. Lek. 2023, 51, 482–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, M.; Pouillon, L.; Mañosa, M.; Savarino, E.; Allez, M.; Kapizioni, C.; Arebi, N.; Carvello, M.; Myrelid, P.; De Vries, A.C.; et al. Results of the Eighth Scientific Workshop of ECCO: Prevention and Treatment of Postoperative Recurrence in Patients with Crohn’s Disease Undergoing an Ileocolonic Resection with Ileocolonic Anastomosis. J. Crohn’s Colitis 2023, 17, 1707–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesio, A.; Zagaria, A.; Baccini, F.; Micheli, F.; Di Nardo, G.; Lombardo, C. A meta-analysis on sleep quality in inflammatory bowel disease. Sleep Med. Rev. 2021, 60, 101518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truta, B. The impact of inflammatory bowel disease on women’s lives. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2021, 37, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, T.H.; Andreoulakis, E.; Alves, G.S.; Miranda, H.L.; Braga, L.L.; Hyphantis, T.; Carvalho, A.F. Associations of sense of coherence with psychological distress and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 6713–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolovich, C.; Bernstein, C.N.; Singh, H.; Nugent, Z.; Tennakoon, A.; Shafer, L.A.; Marrie, R.A.; Sareen, J.; Targownik, L.E. Anxiety and Depression Leads to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Discontinuation in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 19, 1200–1208.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarhayem, A.; Achebe, E.; Logue, A.J. Psychosocial Support of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patient. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 95, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, D.A.; El-Ijla, R.; AbuMusameh, R.R.; Zakout, K.A.; Abu Halima, A.Y.; Abudiab, M.T.; Banat, Y.M.; Alqeeq, B.F.; Al-Tawil, M.; Matar, K. Sex-related differences in profiles and clinical outcomes of Inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024, 24, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Guo, H. Effects of hospital-family holistic care mode on psychological state and nutritional status of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6760–6770. [Google Scholar]

- Opheim, R.; Moum, B.; Grimstad, B.T.; Jahnsen, J.; Prytz Berset, I.; Hovde, Ø.; Huppertz-Hauss, G.; Bernklev, T.; Jelsness-Jørgensen, L.P. Self-esteem in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Qual. Life Res. 2020, 29, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, P.; Rossel, J.B.; Biedermann, L.; Valko, P.O.; Baumann, C.R.; Greuter, T.; Scharl, M.; Vavricka, S.R.; Pittet, V.; Juillerat, P.; et al. Fatigue in inflammatory bowel disease and its impact on daily activities. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 53, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Berre, C.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Danese, S.; Singh, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease Have Similar Burden and Goals for Treatment. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, A.; Khan, S. Systematic review: Outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and de-novo IBD development after bariatric surgery. Surgeon 2023, 21, e71–e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhyani, M.; Joshi, N.; Bemelman, W.A.; Gee, M.S.; Yajnik, V.; D’Hoore, A.; Traverso, G.; Donowitz, M.; Mostoslavsky, G.; Lu, T.K.; et al. Challenges in IBD Research: Novel Technologies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25 (Suppl. 2), S24–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

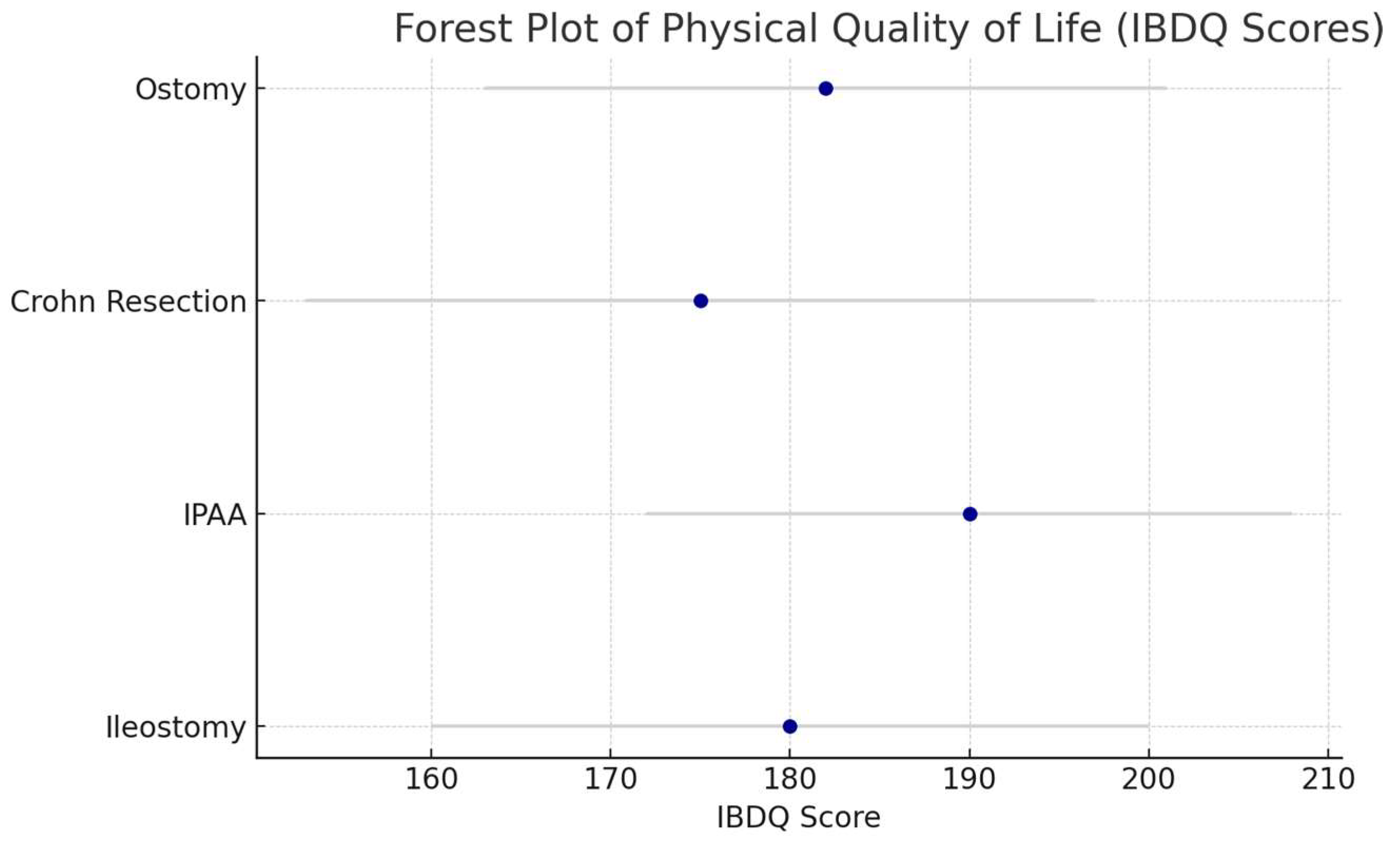

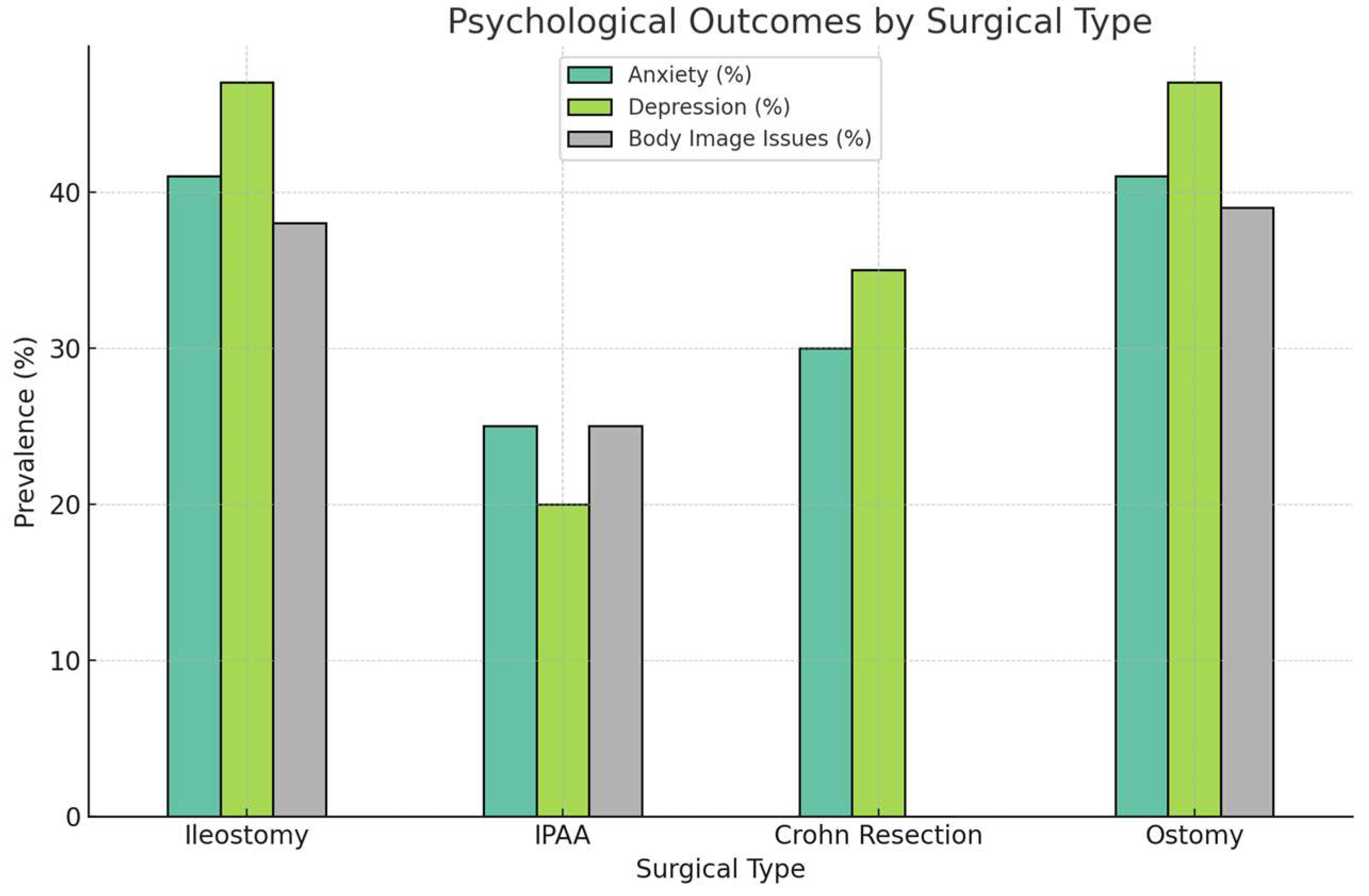

| Surgical Procedure | Physical QoL Outcomes | Psychological QoL Outcomes | Social QoL Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colectomy with Ileostomy | Mean IBDQ: 180 (SD 20); 90% symptom relief | 38% body image issues; 41% anxiety/depression (SF-36 MCS: 45, SD 10) | 34% social isolation | Resolves physical symptoms but introduces psychological and social challenges [2,5] |

| Ileal Pouch–Anal Anastomosis (IPAA) | Mean IBDQ: 190 (SD 18); 85% symptom relief; 28% pouchitis (CGQL: 0.7, SD 0.1) | 25% anxiety; 20% depression (SF-36 MCS: 50, SD 8) | 25% social anxiety due to fecal urgency | Improves physical QoL but complications impact long-term QoL [3,19,24] |

| Resection for Crohn’s Disease | Mean IBDQ: 175 (SD 22); 80% symptom relief; 53% recurrence within 5 years | 30% anxiety; 35% depression (SF-36 MCS: 42, SD 12) | 20% social isolation due to recurrence | High relapse rates lead to declining QoL [4] |

| Ostomy Surgery | Mean IBDQ: 182 (SD 19); 88% symptom relief | 47% depressive symptoms; 41% anxiety/depression (SF-36 MCS: 44, SD 11) | 39% avoided social events due to stigma | Physical benefits tempered by psychological and social stigma [5,6,19] |

| QoL Parameter | Colectomy with Ileostomy | IPAA | Resection for CD | Ostomy Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease-Specific | ||||

| IBDQ Score (mean, SD) | 180 (20) | 190 (18) | 175 (22) | 182 (19) |

| CGQL Score (mean, SD) | 0.65 (0.12) | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.15) | 0.64 (0.13) |

| Pouch Function (% with issues) | N/A | 40% (incontinence, urgency) | N/A | N/A |

| Disease Recurrence (% at 5 years) | 10% | 15% (pouchitis) | 53% | 12% |

| Generic | ||||

| SF-36 PCS (mean, SD) | 48 (9) | 52 (7) | 46 (10) | 47 (8) |

| SF-36 MCS (mean, SD) | 45 (10) | 50 (8) | 42 (12) | 44 (11) |

| Fatigue (% reporting moderate/severe) | 35% | 25% | 40% | 38% |

| Pain Score (mean, SD, 0–10 scale) | 3.5 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.8) | 3.7 (1.6) |

| Domain | Low Risk (%) | Unclear Risk (%) | High Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selection Bias | 55 | 40 | 5 |

| Performance Bias | 20 | 0 | 80 |

| Detection Bias | 60 | 40 | 0 |

| Attrition Bias | 70 | 30 | 0 |

| Reporting Bias | 85 | 15 | 0 |

| Other (Confounding) | 67 | 33 | 0 |

| Outcome | Surgical Type | No. of Studies | Pooled SMD (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical QoL (IBDQ Scores) | All | 45 | 0.85 (0.72, 0.98) | 60 |

| Physical QoL (IBDQ Scores) | IPAA | 25 | 0.92 (0.78, 1.06) | 55 |

| Physical QoL (IBDQ Scores) | Ileostomy | 15 | 0.78 (0.62, 0.94) | 62 |

| Psychological QoL (SF-36 MCS) | All | 30 | 0.45 (0.32, 0.58) | 70 |

| Long-Term QoL (CGQL at 5 Years) | UC (IPAA) | 20 | 0.70 (0.55, 0.85) | 65 |

| Long-Term QoL (CGQL at 5 Years) | CD (Resection) | 15 | 0.50 (0.35, 0.65) | 68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Starcevic, A.; Filipovic, B.; Mijac, D.; Popovic, D.; Lukic, S.; Glisic, T.; Milanovic, M.; Zivic, R.; Popovic, V.S.; Aksic, M. Evaluating Quality of Life in Surgically Treated IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional and Social Impacts. Medicina 2025, 61, 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091662

Starcevic A, Filipovic B, Mijac D, Popovic D, Lukic S, Glisic T, Milanovic M, Zivic R, Popovic VS, Aksic M. Evaluating Quality of Life in Surgically Treated IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional and Social Impacts. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091662

Chicago/Turabian StyleStarcevic, Ana, Branka Filipovic, Dragana Mijac, Dusan Popovic, Snezana Lukic, Tijana Glisic, Miljan Milanovic, Rastko Zivic, Verica Stankovic Popovic, and Milan Aksic. 2025. "Evaluating Quality of Life in Surgically Treated IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional and Social Impacts" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091662

APA StyleStarcevic, A., Filipovic, B., Mijac, D., Popovic, D., Lukic, S., Glisic, T., Milanovic, M., Zivic, R., Popovic, V. S., & Aksic, M. (2025). Evaluating Quality of Life in Surgically Treated IBD Patients: A Systematic Review of Physical, Emotional and Social Impacts. Medicina, 61(9), 1662. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091662