The Psychological Burden of Vitiligo: Investigating the Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Vitiligo: A Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolff, K.; Goldsmith, L.A.; Katz, S.I.; Gilchrest, B.A.; Paller, A.S.; Leffell, D.J. Fitzpatrick’s dermatology in general medicine, 2 volumes. Transplantation 2008, 85, 398. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, R.E.; Zevy, D.L.; Jafferany, M. Psychodermatology of vitiligo: Psychological impact and consequences. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 33, e13418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, Y.; Alrehaili, Y.; Alayoubi, A.M. Impact of consanguinity and familial aggregation on vitiligo epidemiology in Saudi Arabia: A Case-control study. Cureus 2024, 16, e63971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Alayoubi, A.M.; Jannadi, R. First cousin marriages and the risk of childhood-onset vitiligo: Exploring the genetic background: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1471–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, I.A.; Lewinson, R.T.; Parsons, L.M.; Hardin, J.; Haber, R.M.; Lowerison, M.W.; Barnabe, C.; Patten, S.B. Vitiligo and major depressive disorder: A bidirectional population-based cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otte, C.; Gold, S.M.; Penninx, B.W.; Pariante, C.M.; Etkin, A.; Fava, M.; Mohr, D.C.; Schatzberg, A.F. Major depressive disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasser, M.A.; Raggi El Tahlawi, S.M.; Abdelfatah, Z.A.; Soltan, M.R. Stress, anxiety, and depression in patients with vitiligo. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2021, 28, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.M.; Beroukhim, K.; Danesh, M.J.; Babikian, A.; Koo, J.; Leon, A. The psychosocial impact of acne, vitiligo, and psoriasis: A review. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 9, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salman, A.; Kurt, E.; Topcuoglu, V.; Demircay, Z. Social anxiety and quality of life in vitiligo and acne patients with facial involvement: A cross-sectional controlled study. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2016, 17, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silpa-archa, N.; Pruksaeakanan, C.; Angkoolpakdeekul, N.; Chaiyabutr, C.; Kulthanan, K.; Ratta-apha, W.; Wongpraparut, C. Relationship Between Depression and Quality of Life Among Vitiligo Patients: A Self-assessment Questionnaire-based Study. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2020, 13, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singla, S.; Malik, Y.K.; Dayal, S.; Gupta, R. Quality of life, depression, anxiety, stress symptoms, and its association with vitiligo extent and distribution: A cross-sectional study. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2025, 16, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussainova, A.; Kassym, L.; Akhmetova, A.; Glushkova, N.; Sabirov, U.; Adilgozhina, S.; Tuleutayeva, R.; Semenova, Y. Vitiligo and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernwal, D. A study of anxiety and depression in Vitiligo patients: New challenges to treat. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41, S321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molla, A.; Jannadi, R.; Alayoubi, H.; Altouri, H.; Balkhair, M.; Hafez, D. Assessing the relationship between vitiligo and major depressive disorder severity: Cross-sectional study. JMIR Dermatol. 2024, 7, e60686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komen, L.; Da Graça, V.; Wolkerstorfer, A.; De Rie, M.A.; Terwee, C.B.; Van Der Veen, J.P. Vitiligo Area Scoring Index and Vitiligo European Task Force assessment: Reliable and responsive instruments to measure the degree of depigmentation in vitiligo. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlHadi, A.N.; AlAteeq, D.A.; Al-Sharif, E.; Bawazeer, H.M.; Alanazi, H.; AlShomrani, A.T.; Shuqdar, R.M.; AlOwaybil, R. An arabic translation, reliability, and validation of Patient Health Questionnaire in a Saudi sample. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2017, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karia, S.; Sousa, A.D.; Shah, N.; Sonavane, S.; Bharati, A. Psychological morbidity in vitiligo—A case control study. Pigment. Disord. 2015, 2, 2376–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, H.M.; Salem, S.A.; El-Sheshetawy, R.S.; El-Samei, A.M. Comparative study of psychiatric morbidity and quality of life in psoriasis, vitiligo and alopecia areata. Egypt. Dermatol. Online J. 2008, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, N.; Koranne, R.V.; Singh, R.K. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis and vitiligo: A comparative study. J. Dermatol. 2001, 28, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoo, S.K.; Handa, S.; Kaur, I.; Gupta, N.; Malhotra, R. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo and psoriasis: A comparative study from India. J. Dermatol. 2001, 28, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Martín, M.; Melián, D.D.; Rodríguez, M.S.; Cabrera, A.; Bustínduy, M.G. Assessment of Psychiatric Disorders in Vitiligo. Considerations for Our Daily Practice. Depression 2012, 3, 61–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, I.; Ahmed, S.; Nasreen, S. Frequency and pattern of psychiatric disorders in patients with vitiligo. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2007, 19, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rashid, M.H.; Mullick, M.S.; Jaigirdar, M.Q.; Ali, R.; Nirola, D.K.; Salam, M.A.; Ahsan, M.S. Psychiatric morbidity in psoriasis and vitiligo in two tertiary hospitals in Bangladesh. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Med. Univ. J. 2011, 4, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.C.; Yew, Y.W.; Kennedy, C.; Schwartz, R.A. Vitiligo and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.A. Identifying patients at higher risk of depression among patients with vitiligo at outpatient setting. Mater. Socio-Medica 2020, 32, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Category | Vitiligo Patients (n = 340) n (%) | Controls (n = 360) n (%) | Total (n = 700) n (%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

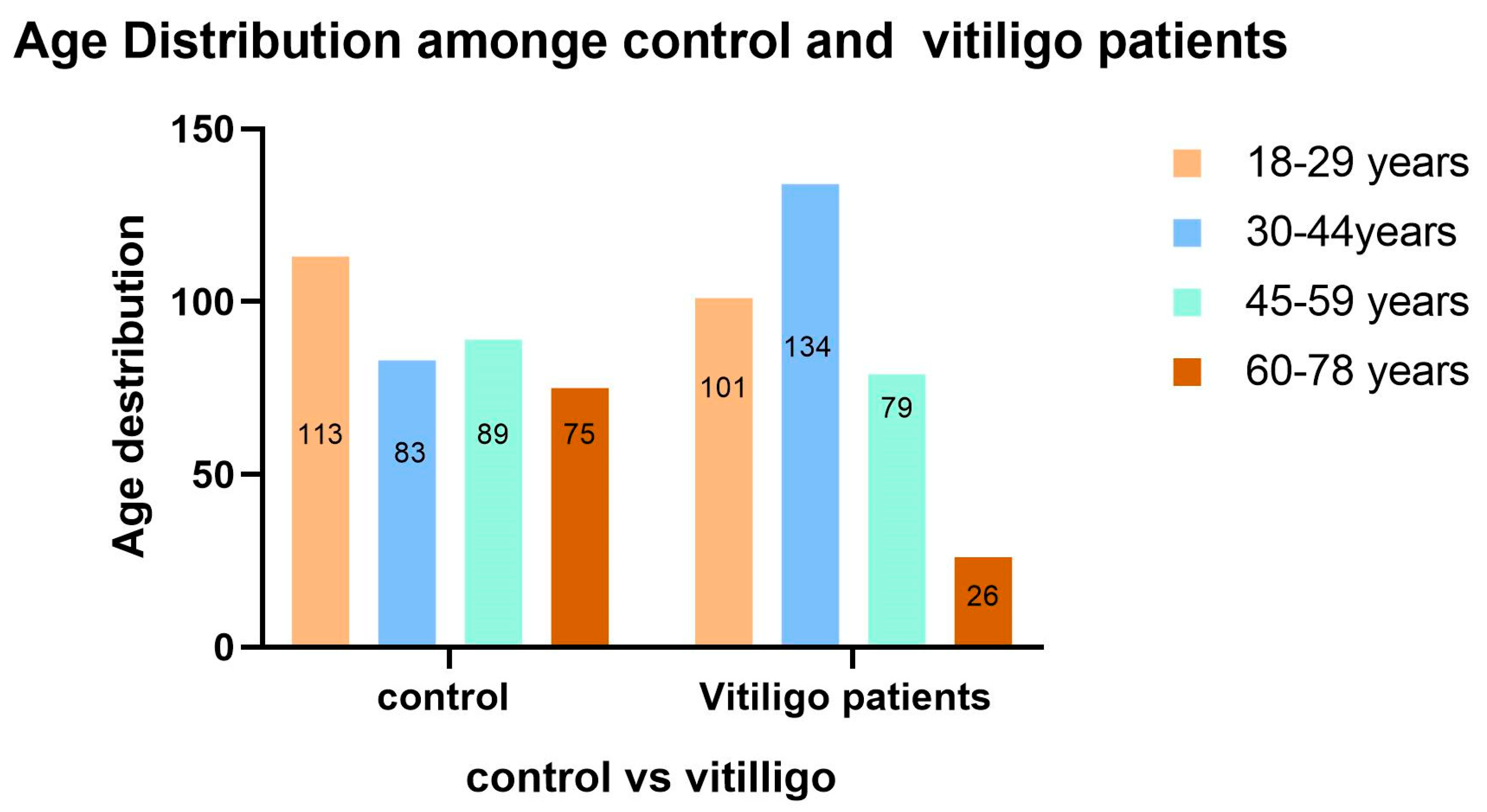

| Age (years) | Mean ± SD | 38.18 ± 13.630 | 41.65 ± 16.127 | 39.96 ± 15.056 | 0.009 |

| Median (IQR) | 36 (22) | 42 (28) | 37 (60) | ||

| Min-Max | 18–76 | 18–78 | 18–78 | ||

| Gender | Female | 156 (45.9) | 189 (52.5) | 345 (49.3) | 0.080 |

| Male | 184 (54.1) | 171 (47.5) | 355 (50.7) | ||

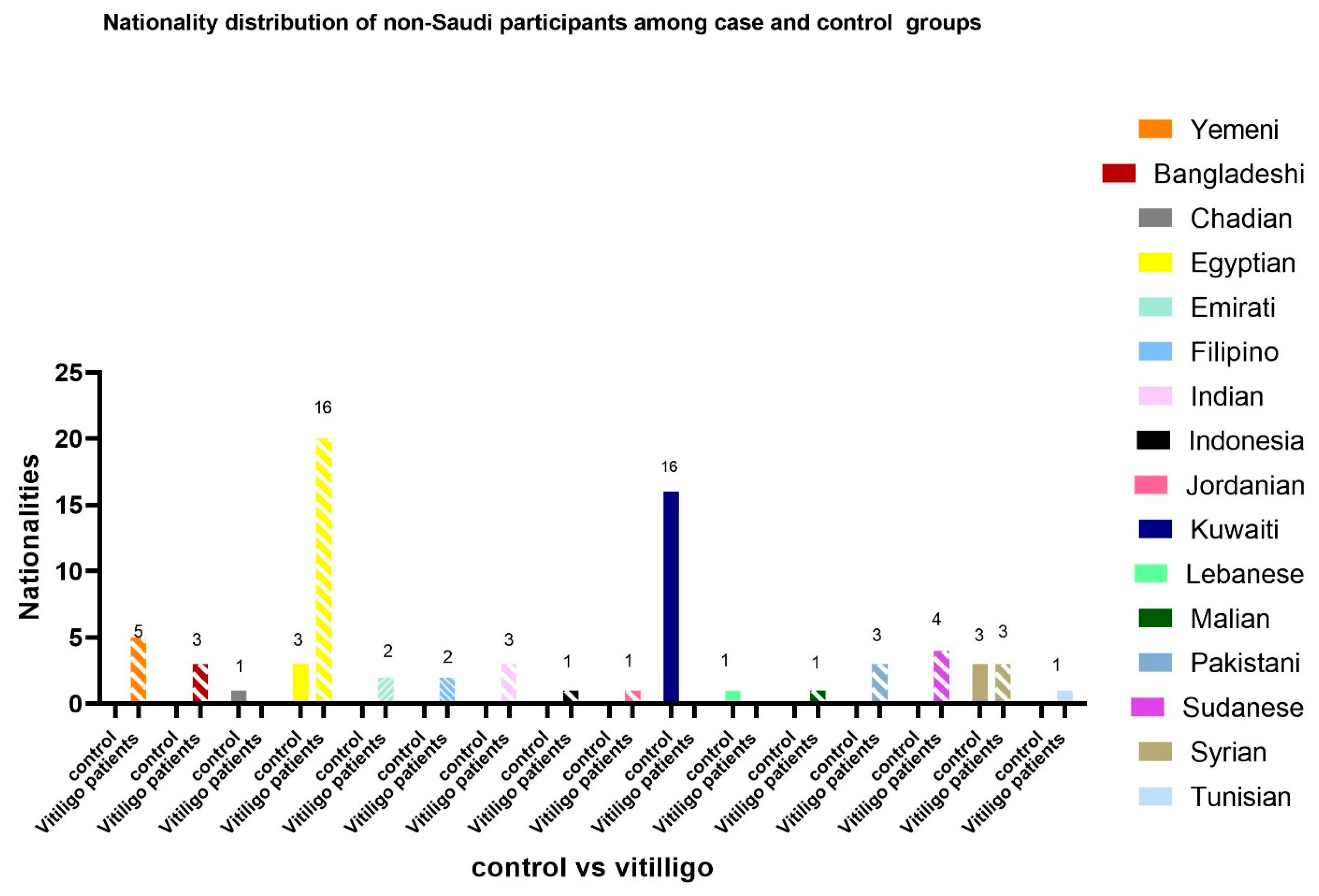

| Nationality | Saudi | 290 (85.3) | 336 (93.3) | 626 (89.4) | 0.001 |

| Non-Saudi | 50 (14.7) | 24 (6.7) | 74 (10.6) | ||

| Marital status | Single | 153 (45) | 118 (32.8) | 271 (38.7) | <0.001 |

| Married | 146 (42.9) | 210 (58.3) | 356 (50.9) | ||

| Divorced | 41 (12.1) | 19 (5.3) | 60 (8.6) | ||

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 13 (3.6) | 13 (1.9) | ||

| Job status | Employed | 128 (37.6) | 162 (45) | 290 (41.4) | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 183 (53.8) | 129 (35.8) | 312 (44.6) | ||

| Student | 29 (8.5) | 69 (19.2) | 98 (14.0) | ||

| Monthly Income | High | 12 (3.5) | 60 (16.7) | 72 (10.3) | <0.001 |

| High-moderate | 43 (12.6) | 104 (28.9) | 147 (21) | ||

| Low-moderate | 32 (9.4) | 101 (28.1) | 133 (19) | ||

| Low | 253 (74.4) | 95 (26.4) | 348 (49.7) |

| Factor | Category | Vitiligo Patients (n = 340) | Controls (n = 360) | Total (n = 700) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | Mean ± SD | 8.28 ± 7.361 | 6.30 ± 4.698 | 7.26 ± 6.211 | 0.028 |

| Median (IQR) | 7 (13) | 6 (6) | 6 (9) | ||

| Min–Max | 0–25 | 0–22 | 0–25 | ||

| Depression severity | None–minimal | 140 (41.2) | 145 (40.3) | 285 (40.7) | <0.001 |

| Mild | 62 (18.2) | 127 (35.3) | 189 (27.0) | ||

| Moderate | 61 (17.9) | 64 (17.8) | 125 (17.9) | ||

| Moderately severe | 40 (11.8) | 21 (5.8) | 61 (8.7) | ||

| Severe depression | 37 (10.9) | 3 (0.8) | 40 (5.7) | ||

| Binary Depression | None–minimal | 140 (41.2) | 145 (40.3) | 285 (40.7) | 0.809 |

| Yes (mild-to-severe) | 200 (58.8) | 215 (59.7) | 415 (59.3) |

| Factor | Category | N (%) | PHQ-9 Median (IQR) | p-Value (Vitiligo Type) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitiligo Type | Acrofacial | 165 (48.5) | 7 (12) | <0.001 |

| Vulgaris | 73 (21.5) | 11 (15) | ||

| Focal | 65 (19.1) | 4 (9) | ||

| Genital | 16 (4.7) | 2.5 (8) | ||

| Universalis | 11 (3.2) | 1 (0) | ||

| Segmental | 10 (2.9) | 9 (17) | ||

| VASI Score | Mean ± SD: 10.4 ± 14.672 | Spearman’s ρ: 0.184 | <0.001 | |

| Median (IQR): 5 (9) | ||||

| Min–Max: 1–92 | ||||

| Factor | Category | VASI Score Median (IQR) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression severity | None–minimal | 5 (9) | 0.033 |

| Mild | 5 (8) | ||

| Moderate | 8 (10) | ||

| Moderately severe | 9.5 (13) | ||

| Severe depression | 8 (12) | ||

| Binary Depression | None–minimal | 5 (9) | 0.015 |

| Yes (Mild-to-severe) | 7 (9) |

| Variable | Category | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Gender (Ref = Male) | Female | 0.716 | 0.377 | 1.360 | 0.308 |

| Nationality (Ref = Non-Saudi) | Saudi | 0.714 | 0.270 | 1.884 | 0.496 |

| Age (Ref ≥ 50) | 18–29 | 0.132 | 0.044 | 0.398 | <0.001 |

| 30–49 | 0.146 | 0.064 | 0.333 | <0.001 | |

| Marital status (Ref = Divorced/Widowed) | Single | 2.057 | 0.628 | 6.738 | 0.233 |

| Married | 2.650 | 0.835 | 8.412 | 0.098 | |

| Job (Ref = Student) | Employed | 1.072 | 0.275 | 4.173 | 0.920 |

| Unemployed | 0.608 | 0.199 | 1.857 | 0.382 | |

| Monthly Income (Ref = Low) | High | 4.946 | 0.924 | 26.487 | 0.062 |

| High–moderate | 9.504 | 2.693 | 33.543 | <0.001 | |

| Low–moderate | 4.510 | 1.410 | 14.431 | 0.011 | |

| VASI score | 0.927 | 0.867 | 0.992 | 0.029 | |

| Vitiligo type (Ref = Segmental) | Acrofacial | 2.312 | 0.338 | 15.834 | 0.393 |

| Vulgaris | 3.620 | 0.459 | 28.515 | 0.222 | |

| Focal | 6.160 | 0.829 | 45.754 | 0.076 | |

| Genital | 12.097 | 1.133 | 129.224 | 0.039 | |

| Universalis | 26,837.836 | 82.925 | 8,685,810.081181 | 0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molla, A.; Albadrani, M. The Psychological Burden of Vitiligo: Investigating the Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Vitiligo: A Case–Control Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091589

Molla A, Albadrani M. The Psychological Burden of Vitiligo: Investigating the Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Vitiligo: A Case–Control Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(9):1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091589

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolla, Amr, and Muayad Albadrani. 2025. "The Psychological Burden of Vitiligo: Investigating the Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Vitiligo: A Case–Control Study" Medicina 61, no. 9: 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091589

APA StyleMolla, A., & Albadrani, M. (2025). The Psychological Burden of Vitiligo: Investigating the Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Vitiligo: A Case–Control Study. Medicina, 61(9), 1589. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61091589