Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts in Adults with ADHD: Findings from a Clinical Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To evaluate the prevalence and modes of SA in a sample of 211 adult patients with ADHD (primary aim);

- (2)

- To identify sociodemographic and clinical characteristics associated with an increased risk of SA or with different modes in these patients (secondary aim).

2. Materials and Methods

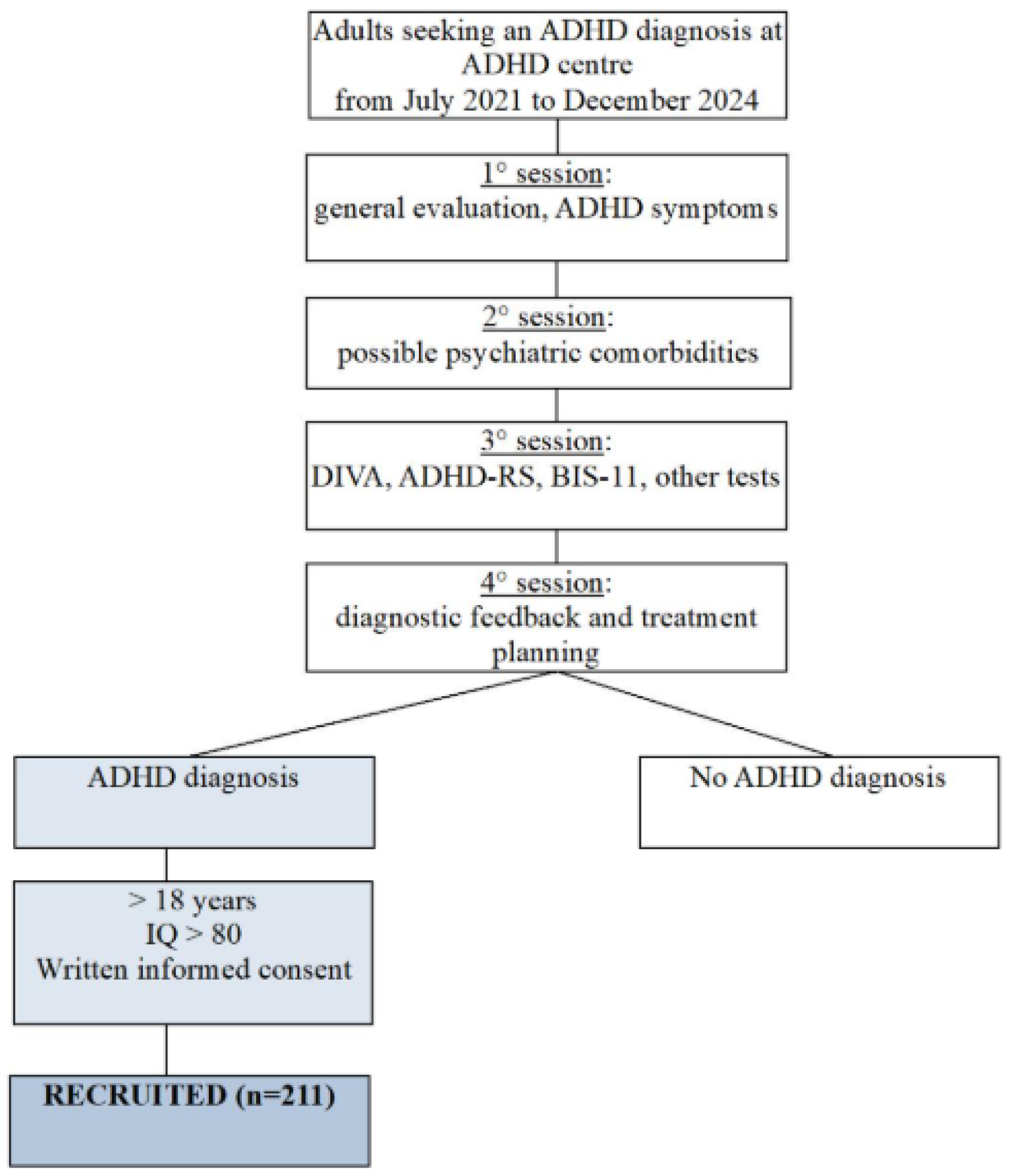

2.1. Study Design and Sample

2.2. Assessment

- (1)

- Sociodemographic data: age, sex, marital status, education level, and occupational status.

- (2)

- Clinical features of ADHD: ADHD subtype; severity of symptoms in childhood and in adulthood (according to the “Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults”—DIVA—which is a validated semi-structured interview for assessing current and childhood ADHD symptoms in adults, demonstrating good test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.85–0.90) and strong convergent validity with other ADHD diagnostic tools [36]); current occurrence of symptoms (measured through the ADHD rating scale IV—ADHD-RS IV—which is a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of ADHD symptoms, demonstrating excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.94) and good convergent validity with other ADHD measures [37]); impulsivity (measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-11—BIS-11 (α = 0.83)—a validated self-report questionnaire assessing cognitive, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness) [38]; ADHD-related symptoms such as mood swings, anger outbursts, low self-esteem (which was evaluated clinically and according to the specific section of Criterion C of DIVA), low tolerance of frustrations, and sleep onset insomnia; areas of functional impairment; age at ADHD diagnosis; age at first ADHD treatment; family history of psychiatric disorders.

- (3)

- (4)

- A history of SA, defined as self-destructive behavior with the intent to end one’s life, regardless of the resulting harm [41], was retrospectively evaluated for each patient, with a focus on the method of SB. Following Stenbacka et al. (2015) [42], SA methods were categorized as violent (hanging, shooting, jumping from a height or moving train, cutting, and drowning) or nonviolent (poisoning). For individuals who had made multiple attempts, the classification was based on the most violent attempt.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leffa, D.T.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. ADHD in Children and Adults: Diagnosis and Prognosis. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 57, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, T.J.; Biederman, J.; Mick, E. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis, Lifespan, Comorbidities, and Neurobiology. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007, 32, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, V.; Czobor, P.; Bálint, S.; Mészáros, A.; Bitter, I. Prevalence and Correlates of Adult Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2009, 194, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; text rev.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, S.; Menard, O.; Ionita, A.; Boumendjel, M.; Cabelguen, C.; Kraemer, C.; Micoulaud-Franchi, J.A.; Bioulac, S.; Perroud, N.; Sauvaget, A. Practical Considerations for the Evaluation and Management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults. Encephale 2020, 46, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzman, M.A.; Bilkey, T.S.; Chokka, P.R.; Fallu, A.; Klassen, L.J. Adult ADHD and Comorbid Disorders: Clinical Implications of a Dimensional Approach. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller-Thomson, E.; Rivière, R.N.; Carrique, L.; Agbeyaka, S. The Dark Side of ADHD: Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts among Those with ADHD in a National Representative Canadian Sample. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 1122–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A.; Koyanagi, A.; Ruchkin, V.; Kamio, Y. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Suicide Ideation and Attempts: Findings from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ljung, T.; Chen, Q.; Lichtenstein, P.; Larsson, H. Common Etiological Factors of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Suicidal Behavior: A Population-Based Study in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Cho, M.J.; Chang, S.M.; Jeon, H.J.; Cho, S.J.; Kim, B.S.; Bae, J.N.; Wang, H.R.; Ahn, J.H.; Hong, J.P. Prevalence, Correlates, and Comorbidities of Adult ADHD Symptoms in Korea: Results of the Korean Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 186, 378–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakuszi, B.; Bitter, I.; Czobor, P. Suicidal Ideation in Adult ADHD: Gender Difference with a Specific Psychopathological Profile. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 85, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septier, M.; Stordeur, C.; Zhang, J.; Delorme, R.; Cortese, S. Association between Suicidal Spectrum Behaviors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 103, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, U.; Boaz, M. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder/Learning Disabilities (ADHD/LD): Parental Characterization and Perception. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 57, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westmoreland, P.; Gunter, T.; Loveless, P.; Allen, J.; Sieleni, B.; Black, D.W. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Men and Women Newly Committed to Prison: Clinical Characteristics, Psychiatric Comorbidity, and Quality of Life. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2010, 54, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, G.C.; Groß, S.; Boreatti, A.; Heine, M.; McNeill, R.V.; Kranz, T.M.; Romanos, M.; Jacob, C.P.; Reif, A.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; et al. Suicidal Behavior in ADHD: The Role of Comorbidity, Psychosocial Adversity, Personality and Genetic Factors. Discov. Ment. Health 2024, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giupponi, G.; Innamorati, M.; Rogante, E.; Sarubbi, S.; Erbuto, D.; Maniscalco, I.; Sanna, L.; Conca, A.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The Characteristics of Mood Polarity, Temperament, and Suicide Risk in Adult ADHD. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, P.; Wiktorsson, S.; Strömsten, L.M.J.; Salander Renberg, E.; Runeson, B.; Waern, M. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults Who Present with Self-Harm: A Comparative 6-Month Follow-Up Study. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.J.; Gelernter, J.; Chan, G.; Weiss, R.D.; Brady, K.T.; Farrer, L.; Kranzler, H.R. Correlates of Co-Occurring ADHD in Drug-Dependent Subjects: Prevalence and Features of Substance Dependence and Psychiatric Disorders. Addict. Behav. 2008, 33, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruchkin, V.; Koposov, R.A.; Koyanagi, A.; Stickley, A. Suicidal Behavior in Juvenile Delinquents: The Role of ADHD and Other Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgulen, A.; Skram, N.K.G.; Haavik, J.; Lundervold, A.J. Risk Factors of Suicidal Spectrum Behaviors in Adults and Adolescents with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder—A Systematic Review. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, C.; Dalsgaard, S.; Nordentoft, M.; Erlangsen, A. Suicidal Behaviour among Persons with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 215, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renaud, J.; Brent, D.A.; Birmaher, B.; Chiappetta, L.; Bridge, J. Suicide in Adolescents with Disruptive Disorders. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1999, 38, 846–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patros, C.H.G.; Hudec, K.L.; Alderson, R.M.; Kasper, L.J.; Davidson, C.; Wingate, L.R. Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Moderate Suicidal Behaviors in College Students with Depressed Mood. J. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 69, 980–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sàez-Francàs, N.; Alegre, J.; Calvo, N.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; Ruiz, E.; Hernández-Vara, J.; Casas, M. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Patients. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Salvo, G.; Perotti, C.; Filippo, L.; Garrone, C.; Rosso, G.; Maina, G. Assessing Suicidality in Adult ADHD Patients: Prevalence and Related Factors. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.K.C.; Coghill, D.; Chan, E.W.; Lau, W.C.Y.; Hollis, C.; Liddle, E.; Banaschewski, T.; McCarthy, S.; Neubert, A.; Sayal, K.; et al. Association of Risk of Suicide Attempts with Methylphenidate Treatment. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 1048–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinshaw, S.P.; Owens, E.B.; Zalecki, C.; Huggins, S.P.; Montenegro-Nevado, A.J.; Schrodek, E.; Swanson, E.N. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 80, 1041–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.R.; Barkley, R.A.; Bush, T. Young adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Subtype differences in comorbidity, educational, and clinical history. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2002, 190, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ludwing, B.; Dwivedy, Y. The Concept of Violent Suicide, Its Underlying Trait and Neurobiology: A Critical Perspective. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brádvik, L. Violent and Nonviolent Methods of Suicide: Different Patterns May Be Found in Men and Women with Severe Depression. Arch. Suicide Res. 2007, 11, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergl, R.; Koburger, N.; Heinrichs, K.; Székely, A.; Ditta, T.M.; Coyne, J.; Quintão, S.; Arensman, E.; Coffey, C.; Maxwell, M.; et al. What Are Reasons for the Large Gender Differences in the Lethality of Suicidal Acts? An Epidemiological Analysis in Four European Countries. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalsman, G.; Braun, M.; Arendt, M.; Grunebaum, M.F.; Sher, L.; Burke, A.K.; Brent, D.A.; Chaudhury, S.R.; John Mann, J.; Oquendo, M.A. A Comparison of the Medical Lethality of Suicide Attempts in Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorders. Bipolar. Disord. 2006, 8, 558–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilgen, M.A.; Conner, K.R.; Valenstein, M.; Austin, K.; Blow, F.C. Violent and Nonviolent Suicide in Veterans with Substance-Use Disorders. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 2010, 71, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zupanc, T.; Agius, M.; Paska, A.V.; Pregelj, P. Blood Alcohol Concentration of Suicide Victims by Partial Hanging. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2013, 20, 976–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheehan, C.M.; Rogers, R.G.; Boardman, J.D. Postmortem Presence of Drugs and Method of Violent Suicide. J. Drug Issues 2015, 45, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, J.J.S.; Francken, M.H. DIVA 2.0. Diagnostic Interview Voor ADHD in Adults bij Volwassenen (DIVA 2.0 Diagnostic Interview ADHD in Adults); DIVA Foundation: Long Beach, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul, G.J.; Power, T.J.; Anastopoulos, A.D.; Reid, R. ADHD Rating Scale-IV: Checklists, Norms, and Clinical Interpretation; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, J.H.; Stanford, M.S.; Barratt, E.S. Factor Structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995, 51, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First, M.B.; Williams, J.B.W.; Karg, R.S.; Spitzer, R.L. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders, Clinician Version (SCID-5-CV); American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Millon, T.; Davis, R.D.; Millon, C. MCMI-III Manual; National Computer Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll, P.W.; Berman, A.L.; Maris, R.W.; Moscicki, E.K.; Tanney, B.L.; Silverman, M.M. Beyond the Tower of Babel: A Nomenclature for Suicidology. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 1996, 26, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenbacka, M.; Jokinen, J. Violent and Non-Violent Methods of Attempted and Completed Suicide in Swedish Young Men: The Role of Early Risk Factors. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://wisqars-viz.cdc.gov:8006/lcd/home (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Dong, M.; Lu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Yuan, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of Suicide Attempts in Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zeng, L.N.; Lu, L.; Li, X.H.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Chow, I.H.I.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of Suicide Attempt in Individuals with Major Depressive Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Surveys. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Dong, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, X.M.; Ungvari, G.S.; Ng, C.H.; Wang, G.; Xiang, Y.T. Prevalence of Suicide Attempts in Individuals with Schizophrenia: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickley, A.; Tachimori, H.; Inoue, Y.; Shinkai, T.; Yoshimura, R.; Nakamura, J.; Morita, G.; Nishii, S.; Tokutsu, Y.; Otsuka, Y.; et al. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms and Suicidal Behavior in Adult Psychiatric Outpatients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 72, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthies, S.; Philipsen, A. Comorbidity of Personality Disorders and Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)—Review of Recent Findings. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2016, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, A.; Lai, F.H.; Dahl, C. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Suicide: A Review of Possible Associations. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2004, 110, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuodelis-Flores, C.; Ries, R.K. Addiction and Suicide: A Review. Focus 2019, 17, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spera, V.; Pallucchini, A.; Maiello, M.; Carli, M.; Maremmani, A.G.I.; Perugi, G.; Maremmani, I. Substance Use Disorder in Adult Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Patients: Patterns of Use and Related Clinical Features. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, J.J.; Khantzian, E.J.; Levin, F.R. The Self-Medication Hypothesis and Psychostimulant Treatment of Cocaine Dependence: An Update. Am. J. Addict. 2014, 23, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, G.; Albert, U.; Bramante, S.; Aragno, E.; Quarato, F.; Di Salvo, G.; Maina, G. Correlates of Violent Suicide Attempts in Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2020, 96, 152136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, L.; Jaussent, I.; Olié, E.; Béziat, S.; Guillaume, S.; Baca-Garcia, E.; Lopez-Castroman, J.; Courtet, P. Violent and Serious Suicide Attempters: One Step Closer to Suicide? J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, e191–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Alford, B.A. Depression: Causes and Treatment; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peñas-Lledó, E.; Guillaume, S.; Delgado, A.; Naranjo, M.E.; Jaussent, I.; Llerena, A.; Courtet, P. ABCB1 Gene Polymorphisms and Violent Suicide Attempt among Survivors. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2015, 61, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayle, F.J.; Leroy, S.; Gourion, D.; Millet, B.; Olie, J.P.; Poirier, M.F.; Krebs, M.O. 5HTTLPR Polymorphism in Schizophrenic Patients: Further Support for Association with Violent Suicide Attempts. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 2003, 119B, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scocco, P.; Castriotta, C.; Toffol, E.; Preti, A. Stigma of Suicide Attempt (STOSA) Scale and Stigma of Suicide and Suicide Survivor (STOSASS) Scale: Two New Assessment Tools. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 200, 872–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total Sample (n = 211) | SA Group (21) | Non-SA Group (190) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.614 | |||

| Male | 141 (66.8) | 13 (61.9) | 128 (67.4) | |

| Female | 70 (33.2) | 8 (38.1) | 62 (32.6) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 27.41 (9.380) | 28 (10.085) | 27.27 (9.339) | 0.735 |

| Age at diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 24.9 (10.336) | 24.71 (9.885) | 24.90 (10.414) | 0.939 |

| Age at first ADHD treatment (years), mean (SD) | 25.1 (9.793) | 25.24 (9.196) | 25.08 (9.876) | 0.950 |

| Educational level, mean (SD) | 12 (3.284) | 11.10 (2.809) | 13.09 (3.304) | 0.008 |

| Current occupation, n (%) | 0.109 | |||

| Unemployed | 61 (28.9) | 12 (57.1) | 49 (25.8) | |

| Student | 56 (26.5) | 4 (19.0) | 54 (28.4) | |

| Worker | 94 (44.6) | 5 (23.9) | 87 (45.8) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.144 | |||

| Single | 178 (84.4) | 20 (95.2) | 159 (83.6) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 28 (13.3) | 0 (0) | 27 (14.2) | |

| Separated | 5 (2.4) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Current smoking | 89 (42.2) | 14 (66.7) | 74 (38.9) | 0.016 |

| Physical activity | 96 (45.5) | 5 (23.8) | 91 (47.9) | 0.032 |

| Family history of psychiatric disorders, n (%) | 97 (45.9) | 8 (38.1) | 89 (46.8) | 0.397 |

| Adult ADHD subtype, n (%) | 0.026 | |||

| Inattentive subtype | 99 (46.9) | 4 (19.0) | 95 (50.0) | |

| Combined subtype | 112 (53.1) | 17 (81.0) | 95 (50.0) | |

| Childhood ADHD subtype, n (%) | 0.108 | |||

| Inattentive subtype | 75 (35.5) | 4 (19.0) | 71 (37.4) | |

| Combined subtype | 136 (64.5) | 17 (81.0) | 119 (62.6) | |

| BIS-11, mean (SD) | 70.4 (11.679) | 77.5 (8.668) | 69.78 (11.743) | 0.77 |

| ADHD-RS pre-treatment, mean (SD) | 35.5 (8.267) | 35.07 (7.583) | 35.56 (8.378) | 0.828 |

| Number of symptoms in childhood, mean (SD) | ||||

| Inattentive | 7.3 (1.316) | 7.69 (1.109) | 7.35 (1.336) | 0.369 |

| Hyperactive–impulsive | 5.3 (2.812) | 6.46 (2.402) | 5.28 (2.844) | 0.149 |

| Number of symptoms in adulthood, mean (SD) | ||||

| Inattentive | 7.2 (1.464) | 8.00 (1.155) | 7.12 (1.473) | 0.038 |

| Hyperactive–impulsive | 5.3 (2.473) | 6.46 (2.402) | 5.24 (2.465) | 0.115 |

| Lifetime psychiatric comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Any comorbid disorder | 152 (72.0) | 21 (100) | 131 (68.9) | 0.002 |

| Personality disorders | 30 (14.2) | 11 (52.4) | 19 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Substance use disorders | 64 (30.3) | 11 (52.4) | 53 (27.9) | 0.016 |

| Stimulant use disorder | 37 (17.5) | 7 (33.3) | 30 (15.8) | 0.048 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 8 (3.8) | 2 (9.5) | 6 (3.1) | 0.151 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 52 (24.6) | 8 (38.1) | 44 (23.1) | 0.123 |

| Major depressive disorder | 58 (27.5) | 8 (38.1) | 50 (26.3) | 0.264 |

| Bipolar disorders | 23 (10.9) | 2 (9.5) | 21 (11.0) | 0.933 |

| Areas of functional impairment, n (%) | ||||

| Social functioning | 123 (58.3) | 19 (90.5) | 104 (54.7) | 0.008 |

| Relational functioning | 152 (72.0) | 21 (100) | 131 (68.9) | 0.003 |

| Academic functioning | 192 (90.9) | 19 (90.5) | 173 (91.0) | 0.740 |

| Occupational functioning | 153 (72.5) | 19 (90.5) | 134 (70.5) | 0.155 |

| Related symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Mood swings | 155 (73.5) | 20 (95.2) | 135 (71.0) | 0.020 |

| Anger outbursts | 114 (54.0) | 17 (81.0) | 97 (51.0) | 0.010 |

| Low self-esteem | 156 (73.9) | 19 (90.5) | 137 (72.1) | 0.077 |

| Low tolerance of frustrations | 145 (68.7) | 21 (100) | 124 (65.3) | 0.001 |

| Number of hospitalizations | 0.6 (3.618) | 4.38 (10.712) | 0.23 (0.825) | <0.001 |

| Violent SA (5) | Nonviolent SA (16) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | 0.340 | ||

| Male | 4 (80.0) | 9 (56.2) | |

| Female | 1 (20.0) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 28.60 (10.237) | 27.81 (10.368) | 0.883 |

| Age at diagnosis (years), mean (SD) | 23.80 (14.653) | 25 (8.524) | 0.820 |

| Age at first ADHD treatment (years), mean (SD) | 28.49 (10.644) | 23.92 (8.681) | 0.377 |

| Educational level | 11.60 (3.507) | 10.94 (2.670) | 0.657 |

| Current occupation, n (%) | 0.742 | ||

| Unemployed | 2 (40.0) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Student | 1 (20.0) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Worker | 2 (40.0) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | 0.067 | ||

| Single | 4 (80.0) | 16 (100) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Separated | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Current smoking | 3 (60.0) | 11 (68.8) | 0.717 |

| Physical activity | 2 (40.0) | 3 (18.8) | 0.330 |

| Family history of psychiatric disorders, n (%) | 4 (80.0) | 9 (56.3) | 0.340 |

| Adult ADHD subtype, n (%) | 0.214 | ||

| Inattentive subtype | 0 (0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Combined subtype | 5 (100) | 12 (75.0) | |

| Childhood ADHD subtype, n (%) | 0.214 | ||

| Inattentive subtype | 0 (0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| Combined subtype | 5 (100) | 12 (75.0) | |

| BIS-11, mean (SD) | 85.50 (13.435) | 74.83 (5.913) | 0.141 |

| ADHD-RS pre-treatment, mean (SD) | 37.67 (12.741) | 34.42 (6.431) | 0.527 |

| Number of symptoms in childhood, mean (SD) | |||

| Inattentive | 8.67 (0.577) | 7.40 (1.075) | 0.081 |

| Hyperactive–impulsive | 7.67 (1.528) | 6.10 (2.558) | 0.343 |

| Number of symptoms in adulthood, mean (SD) | |||

| Inattentive | 8.00 (1.000) | 8.00 (1.247) | 1.000 |

| Hyperactive–impulsive | 7.67 (1.528) | 6.00 (2.667) | 0.333 |

| Lifetime psychiatric comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Any psychiatric comorbidities | 5 (100) | 16 (100) | — |

| Personality disorders | 2 (40.0) | 9 (56.3) | 0.525 |

| Substance use disorders | 2 (40.0) | 9 (56.3) | 0.525 |

| Stimulant use disorder | 2 (40.0) | 5 (31.3) | 0.717 |

| Alcohol use disorder | 1 (20.0) | 1 (6.3) | 0.361 |

| Cannabis use disorder | 1 (20.0) | 7 (43.8) | 0.340 |

| Major depressive disorder | 2 (40.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.920 |

| Bipolar disorders | 0 (0.00) | 2 (12.5) | 0.406 |

| Areas of functional impairment, n (%) | |||

| Social functioning | 5 (100) | 14 (87.5) | 0.406 |

| Relational functioning | 5 (100) | 16 (100) | — |

| Academic functioning | 4 (80.0) | 15 (93.8) | 0.361 |

| Occupational functioning | 4 (80.0) | 15 (93.8) | 0.166 |

| Related symptoms, n (%) | |||

| Mood swings | 5 (100) | 15 (93.8) | 0.567 |

| Anger outbursts | 4 (80.0) | 13 (81.3) | 0.950 |

| Low self-esteem | 3 (60.0) | 16 (100) | 0.008 |

| Low tolerance of frustrations | 5 (100) | 16 (100) | — |

| Number of psychiatric hospitalizations | 1.20 (1.095) | 5.38 (12.176) | 0.461 |

| B | SE | Wald | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational level | −0.010 | 0.104 | 0.010 | 0.920 | 0.990 | 0.801–1.212 |

| Current smoking | −0.651 | 0.847 | 0.590 | 0.553 | 0.522 | 0.103–2.918185–1.676 |

| Physical activity | −1.127 | 0.684 | 2.719 | 0.099 | 0.324 | 0.083–1.204 |

| Adult ADHD subtype | 16.574 | 2559.3 | 0.000 | 0.759 | 5771.7 | 0.425–9–275 |

| No. of inattentive symptoms in adult | 0.721 | 0.518 | 1.937 | 0.164 | 2.057 | 0.761–2.465 |

| Lifetime psychiatric comorbidities | ||||||

| Any comorbid disorder | 16.640 | 4197.9 | 0.000 | 0.997 | 14,579.3 | 0.000 |

| Personality disorders | 1.889 | 0.688 | 7.536 | 0.006 | 6.613 | 1.729–20.847 |

| Substance use disorders | −1.452 | 1.083 | 1.797 | 0.180 | 0.180 | 0.023–1.632 |

| Stimulant use disorder | 1.065 | 0.978 | 1.185 | 0.276 | 0.276 | 0.526–9.432 |

| Mood swings | 0.777 | 1.236 | 0.395 | 0.425 | 2.176 | 0.235–31.052 |

| Anger outbursts | −0.016 | 0.861 | 0.000 | 0.985 | 0.984 | 0.179–5.650 |

| Low tolerance of frustrations | 21.314 | 2577.5 | 0.000 | 0.997 | 37,945.6 | 0.000 |

| Social functioning impairment | −0.239 | 0.626 | 0.146 | 0.659 | 0.788 | 0.128–3.678 |

| Relational functioning impairment | 24.997 | 6510.5 | 0.000 | 0.997 | 71,765 | 0.000 |

| Number of psychiatric hospitalizations | 0.683 | 0.256 | 7.124 | 0.008 | 1.980 | 0.296–2.675 |

| Constant | −65.176 | 7559.5 | 0.000 | 0.993 | 0.000 | −88.49–−51.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perotti, C.; Rosso, G.; Garrone, C.; Ricci, V.; Maina, G.; Di Salvo, G. Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts in Adults with ADHD: Findings from a Clinical Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071178

Perotti C, Rosso G, Garrone C, Ricci V, Maina G, Di Salvo G. Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts in Adults with ADHD: Findings from a Clinical Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(7):1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071178

Chicago/Turabian StylePerotti, Camilla, Gianluca Rosso, Camilla Garrone, Valerio Ricci, Giuseppe Maina, and Gabriele Di Salvo. 2025. "Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts in Adults with ADHD: Findings from a Clinical Study" Medicina 61, no. 7: 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071178

APA StylePerotti, C., Rosso, G., Garrone, C., Ricci, V., Maina, G., & Di Salvo, G. (2025). Factors Associated with Suicide Attempts in Adults with ADHD: Findings from a Clinical Study. Medicina, 61(7), 1178. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61071178