Clinical Profiles and Medication Predictors in Early Childhood Psychiatric Referrals: A 10-Year Retrospective Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Statistical Analysis

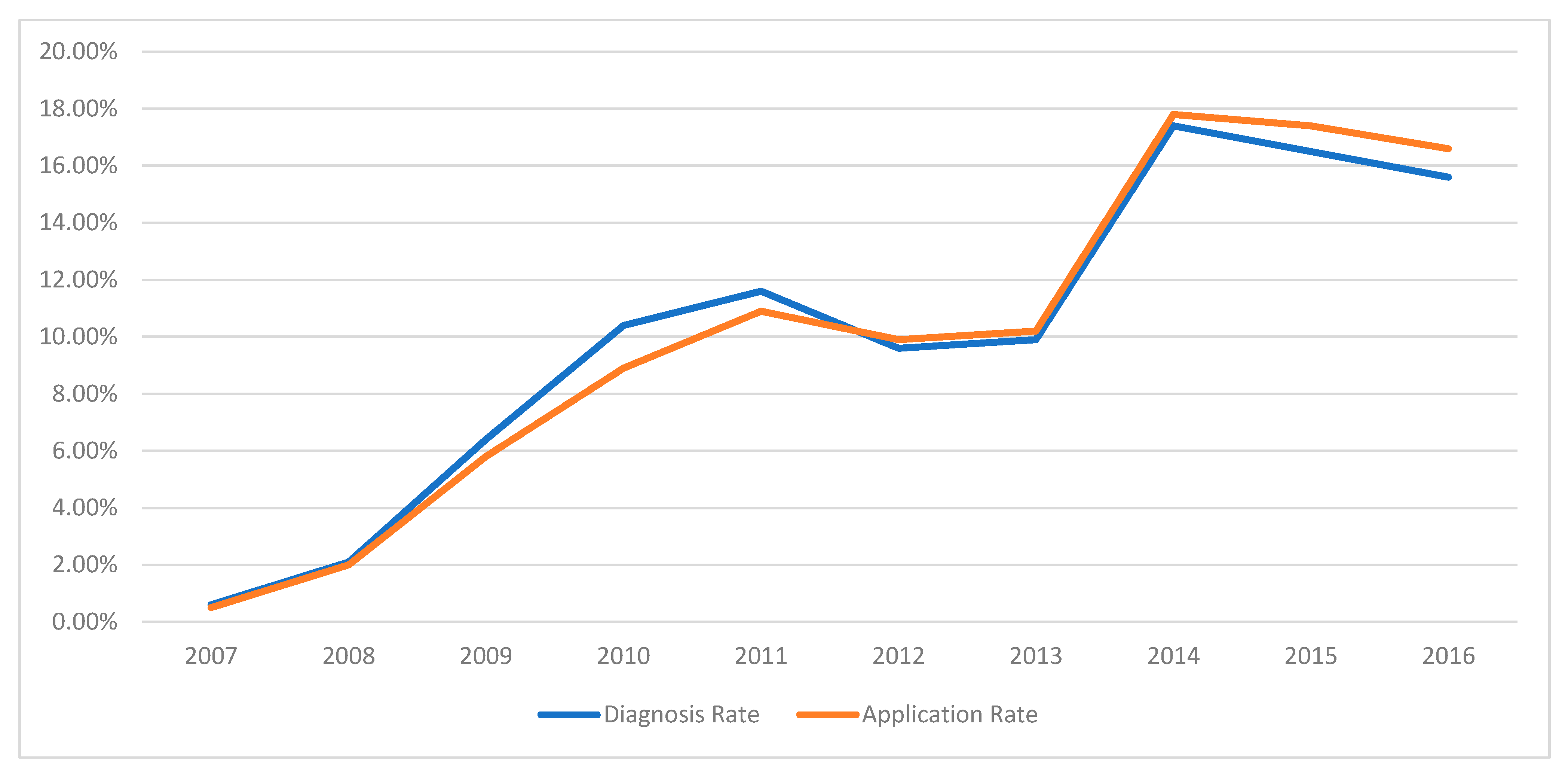

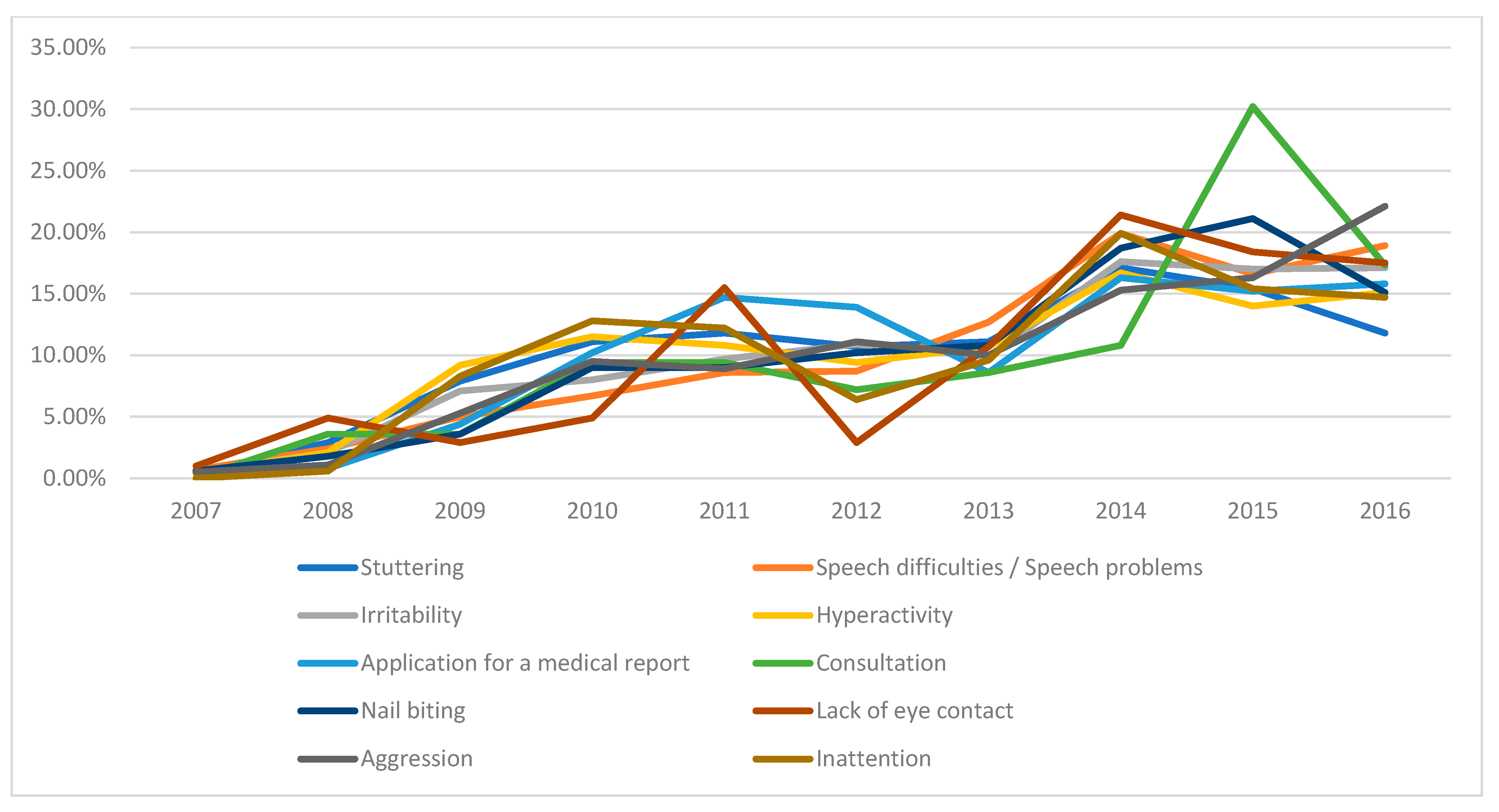

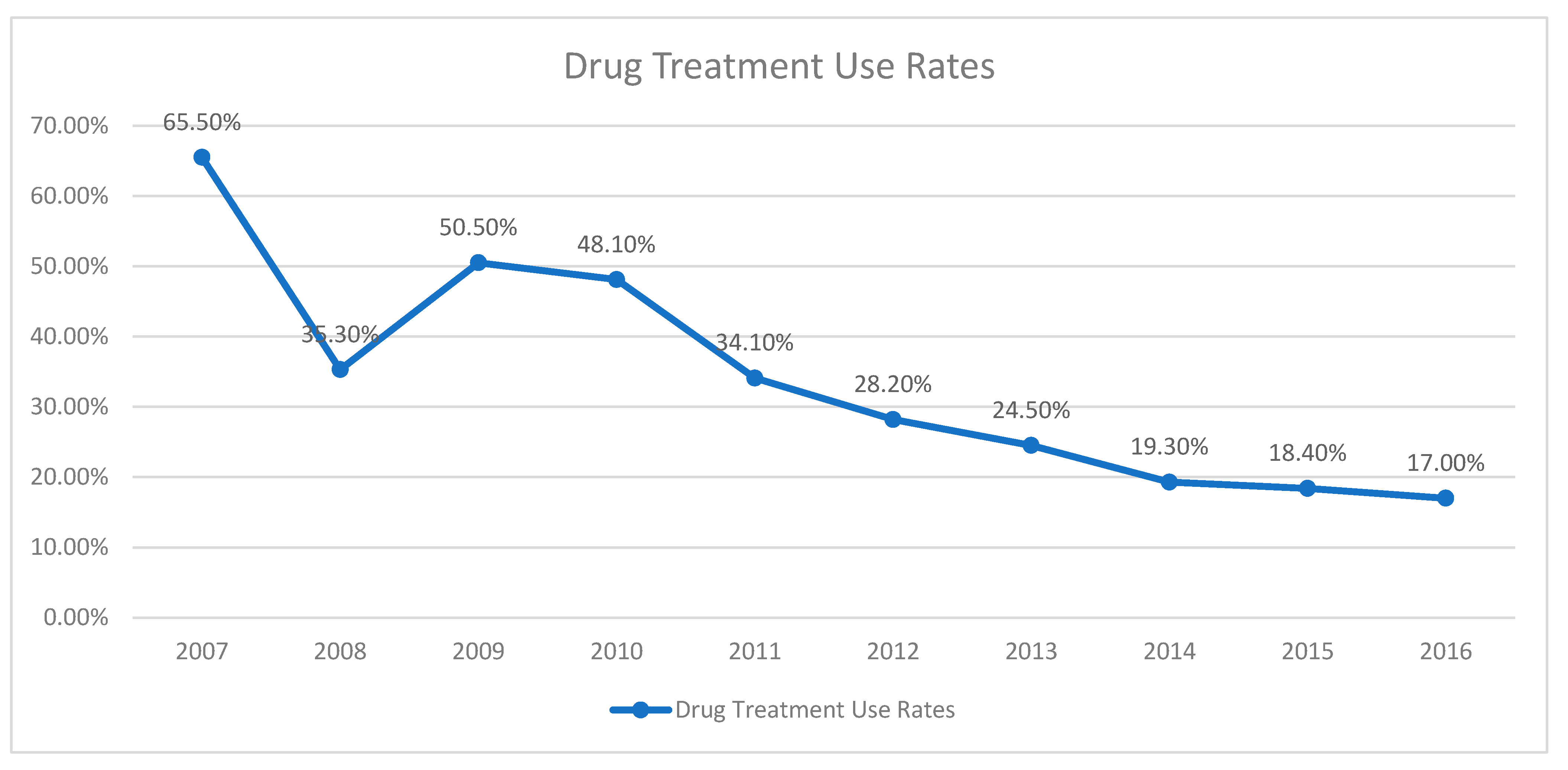

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knitzer, J. Early childhood mental health services: A policy and systems development perspective. Handb. Early Child. Interv. 2000, 2, 416–438. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, B.S. Early life influences on life-long patterns of behavior and health. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2003, 9, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angold, A.; Egger, H.L. Preschool psychopathology: Lessons for the lifespan. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2007, 48, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons-Ruth, K.; Todd Manly, J.; Von Klitzing, K.; Tamminen, T.; Emde, R.; Fitzgerald, H.; Paul, C.; Keren, M.; Berg, A.; Foley, M.; et al. The worldwide burden of infant mental and emotional disorder: Report of the task force of the world association for infant mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2017, 38, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, H.L.; Angold, A. Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2006, 47, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileva, M.; Graf, R.K.; Reinelt, T.; Petermann, U.; Petermann, F. Research review: A meta-analysis of the international prevalence and comorbidity of mental disorders in children between 1 and 7 years. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Klitzing, K.; Döhnert, M.; Kroll, M.; Grube, M. Mental disorders in early childhood. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2015, 112, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skovgaard, A.M. Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. Dan Med Bull 2010, 57, B4193. [Google Scholar]

- Wichstrøm, L.; Berg-Nielsen, T.S.; Angold, A.; Egger, H.L.; Solheim, E.; Sveen, T.H. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatice Sevgen, F.; Altun, H. Çocuk ve Ergen Psikiyatrisi Polikliniğine Başvuran 0–5 Yaş Arası Çocukların Başvuru Şikayetleri ve Psikiyatrik Tanıları. JoMD 2017, 7, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, N.; Coe, C. Social patterning and prediction of parent-reported behaviour problems at 3 years in a cohort study. Child Care Health Dev. 2003, 29, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Carter, A.S.; Skuban, E.M.; Horwitz, S.M. Prevalence of social-emotional and behavioral problems in a community sample of 1-and 2-year-old children. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2001, 40, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Fornaro, M.; Ostinelli, E.G.; Zangani, C.; Croatto, G.; Monaco, F.; Krinitski, D.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Correll, C.U. Safety of 80 antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-attention-deficit/hyperactivity medications and mood stabilizers in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: A large scale systematic meta-review of 78 adverse effects. World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, D. The psychiatry of children aged 0–4: Advances in assessment, diagnosis and treatment. BJPsych Adv. 2015, 21, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, B. Pediatric psychopharmacology and the interaction between drugs and the developing brain. Can. J. Psychiatry 1998, 43, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usta, M.B.; Gumus, Y.Y.; Aral, A.; Say, G.N.; Karabekiroglu, K. Psychotropic medication use in children and adolescents: Review of outpatient treatments. Dusunen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2018, 31, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorberg, B. Pediatric Psychopharmacology Evidence: A Clinician’s Guide; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Isik, C.M.; Baysal, S.G. Complaints, diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment of patients applying to 0–6 years old child psychiatry and developmental pediatrics outpatient clinic. Ann. Med. Res. 2024, 31, 269–344. [Google Scholar]

- Uygun, S.D.; Goker, Z.; Acikel, S.B.; Dinc, G.; Hekim, O.; Cop, E.; Uneri, O.S. Psychotropic drug use in preschool and toddler age groups: An evaluation of hospital admissions. Psychiatry Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, D.; Kara, K.; Durukan, İ. Çocuk ve Ergen Psikiyatrisine Başvuran Hastalara Tedavi Uygulamaları. Anatol. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 6, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tanrıöver, S.; Kaya, N.; Tüzün, Ü.; Aydoğmuş, K. Çocuk Psikiyatrisi Polikliniğine Başvuran Çocukların Demografik Özellikleri ile İlgili Bir Çalışma. Düşünen Adam Psikiyatr. Nörolojik Bilim. Derg. 1992, 5, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; D’Arcy, C.; Meng, X. Predictors of functional improvement in children and adolescents at a publicly funded specialist outpatient treatment clinic in a Canadian Prairie City. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coskun, M.; Kaya, İ. Prevalence and patterns of psychiatric disorders in preschool children referred to an outpatient psychiatry clinic. Anatol. Clin. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 21, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Aras, Ş.; Ünlü, G.; Taş, F.V. Çocuk ve Ergen Psikiyatrisine Başvuran Hastalarda Belirtiler, Tanılar ve Tanıya Yönelik İncelemeler. Klin. Psikiyatr. Derg. 2007, 10, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Taş, F.V.; Janbakhishov, C.E.; Karaarslan, D. Bir üniversite kliniği deneyimi: Erken çocukluk döneminde psikotrop ilaç kullanımı. Çocuk Gençlik Ruh Sağlığı Derg. 2015, 22, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Durukan, İ.; Karaman, D.; Kara, K.; Türker, T.; Tufan, A.E.; Yalçın, Ö.; Karabekiroğlu, K. Diagnoses of patients referring to a child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic. Dusunen Adam J. Psychiatry Neurol. Sci. 2011, 24, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araz Altay, M.; Bozatlı, L.; Demirci Şipka, B.; Görker, I. Current pattern of psychiatric comorbidity and psychotropic drug prescription in child and adolescent patients. Medicina 2019, 55, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Text revision; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J. Antianxiety agents and hypnotics. In Drug Therapy in Psychiatry, 3rd ed.; Mosby-Year Book Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1995; pp. 44–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbek, A.; Bozabali, O. The use of psychotropic medication in pre-schoolers. Klin. Psikofarmakol. Bülteni 2003, 13, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Fontanella, C.A.; Hiance, D.L.; Phillips, G.S.; Bridge, J.A.; Campo, J.V. Trends in psychotropic medication use for Medicaid-enrolled preschool children. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirdkiatgumchai, V.; Xiao, H.; Fredstrom, B.K.; Adams, R.E.; Epstein, J.N.; Shah, S.S.; Brinkman, W.B.; Kahn, R.S.; Froehlich, T.E. National trends in psychotropic medication use in young children: 1994–2009. Pediatrics 2013, 132, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean ± s.d./n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | 46.59 ± 16.48 (Min 1-Max 72, Median 48) | |

| Sex | Girl | 1174 (35.4%) |

| Boy | 2138 (64.6%) | |

| School/nursery status | Kindergarten | 540 (16.3%) |

| Nursery | 372 (11.2%) | |

| Special education | 116 (3.5%) | |

| Not going to school | 1741 (52.6%) | |

| First grade | 121 (3.7%) | |

| Missing | 422 (12.7%) | |

| Mother’s education | Illiterate | 80 (2.4%) |

| Primary–secondary school | 1197 (36.1%) | |

| High school | 770 (23.2%) | |

| University–college | 560 (16.9%) | |

| Missing | 713 (21.5%) | |

| Mother’s psychiatric illness | Yes | 298 (9.0%) |

| No | 2404 (72.6%) | |

| Missing | 618 (18.7%) | |

| Father’s education | Illiterate | 40 (1.2%) |

| Primary–secondary school | 1095 (33.1%) | |

| High school | 834 (25.2%) | |

| University–college | 612 (18.5%) | |

| Missing | 739 (22.3%) | |

| Father’s psychiatric illness | Yes | 102 (3.1%) |

| No | 2559 (77.3%) | |

| Missing | 659 (19.9%) | |

| Presenting Complaint | Diagnosed | Undiagnosed | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Speech delay | 531 (28.4%) | 275 (19.1%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Irritability | 337 (18.0%) | 412 (28.6%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Hyperactivity | 309 (16.5%) | 253 (17.5%) | 0.438 X2 |

| Application for a medical report | 273 (14.6%) | 84 (5.8%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Stuttering | 243 (13.0%) | 37 (2.6%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Aggression | 102 (5.5%) | 88 (6.1%) | 0.426 X2 |

| Inattention | 95 (5.1%) | 61 (4.2%) | 0.252 X2 |

| Lack of eye contact | 81 (4.3%) | 22 (1.5%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Nail biting | 63 (3.4%) | 102 (7.1%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Bedwetting | 63 (3.4%) | 24 (1.7%) | 0.002 X2 |

| Soiling | 62 (3.3%) | 10 (0.7%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Toilet training problems | 25 (1.3%) | 49 (3.4%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Consultation | 18 (1.0%) | 122 (8.5%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Sleep problems | 45 (2.4%) | 50 (3.5%) | 0.070 X2 |

| Social withdrawal | 45 (2.4%) | 42 (2.9%) | 0.366 X2 |

| Fears | 34 (1.8%) | 47 (3.3%) | 0.008 X2 |

| Impaired comprehension | 38 (2.0%) | 12 (0.8%) | 0.005 X2 |

| Developmental delay | 46 (2.5%) | 12 (0.8%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Sibling jealousy | 16 (0.9%) | 50 (3.5%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Frequent crying | 30 (1.6%) | 57 (4.0%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Not responding to one’s name | 54 (2.9%) | 13 (0.9%) | 0.000 X2 |

| School refusal | 35 (1.9%) | 36 (2.5%) | 0.218 X2 |

| Masturbation | 36 (1.9%) | 7 (0.5%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Eating issues/feeding problems | 36 (1.9%) | 39 (2.7%) | 0.167 X2 |

| Difficulty separating from the mother | 29 (1.6%) | 18 (1.2%) | 0.465 X2 |

| Easily bored | 12 (0.6%) | 12 (0.8%) | 0.522 X2 |

| Discomfort with one’s gender | 2 (0.1%) | 10 (0.7%) | 0.005 X2 |

| Obsessions | 24 (1.3%) | 29 (2.0%) | 0.098 X2 |

| Somatic complaints | 6 (0.3%) | 22 (1.5%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Tics | 22 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.000 X2 |

| Frequent lying | 3 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0.873 X2 |

| Stereotypical behaviors | 24 (1.3%) | 11 (0.8%) | 0.146 X2 |

| Picky eating | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.435 X2 |

| Girls | Boys | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± s.d. (Median)/n (%) | Mean ± s.d. (Median)/n (%) | |||

| Age (months) | 45.5 ± 16.7 (46) | 47.2 ± 16.3 (48) | 0.007 m | |

| Diagnosis | 0.000 X2 | |||

| Yes | 614 (52.3%) | 1256 (58.7%) | ||

| No | 560 (47.7%) | 882 (41.3%) | ||

| Missing | 2 | 6 | ||

| Diagnosis count | 1 | 549 (89.4%) | 1118 (89.0%) | 0.794 X2 |

| 2 | 60 (9.8%) | 131 (10.4%) | ||

| 3 | 4 (0.7%) | 6 (0.5%) | ||

| 4 | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | ||

| Developmental Delay | 143 (23.3%) | 247 (19.7%) | 0.592 X2 | |

| ADHD | 61 (9.9%) | 268 (21.3%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| Stuttering | 83 (13.5%) | 138 (11.0%) | 0.497 X2 | |

| Speech Disorder | 59 (9.6%) | 127 (10.1%) | 0.274 X2 | |

| ASD | 45 (7.3%) | 119 (9.5%) | 0.028 X2 | |

| Anxiety Disorder | 81 (13.2%) | 79 (6.3%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| RAD | 26 (4.2%) | 108 (8.6%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| Behavioral Disorder | 33 (5.4%) | 96 (7.6%) | 0.017 X2 | |

| Encopresis | 18 (2.9%) | 51 (4.1%) | 0.100 X2 | |

| Enuresis | 27 (4.4%) | 33 (2.6%) | 0.118 X2 | |

| Intellectual Disability | 29 (4.7%) | 28 (2.2%) | 0.014 X2 | |

| Specific Learning Disorder | 11 (1.8%) | 24 (1.9%) | 0.617 X2 | |

| Masturbation | 24 (3.9%) | 10 (0.8%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| Sleep Disorder | 17 (2.8%) | 14 (1.1%) | 0.023 X2 | |

| Tic Disorder | 3 (0.5%) | 22 (1.8%) | 0.014 X2 | |

| Eating Disorder | 3 (0.5%) | 9 (0.7%) | 0.449 X2 | |

| Adjustment Disorder | 5 (0.8%) | 7 (0.6%) | 0.652 X2 | |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 4 (0.7%) | 6 (0.5%) | 0.763 X2 | |

| Depression | 5 (0.8%) | 3 (0.2%) | 0.109 X2 | |

| Trichotillomania | 3 (0.5%9) | 2 (0.2%) | 0.354 X2 | |

| Neglect/Abuse | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1.000 X2 | |

| Stereotypic Movement Disorder | 1 (0.2%) | 2 (0.2%) | 1.000 X2 | |

| Gender Dysphoria | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1.000 X2 | |

| Somatization Disorder | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.354 X2 | |

| Clinical follow-up duration | 0.002 X2 | |||

| Single evaluation | 573 (48.5%) a | 932 (43.5%) b | ||

| 1–6 months | 355 (30.1%) a | 637 (29.8%) a | ||

| 7–12 months | 105 (8.9%) a | 204 (9.5%) a | ||

| 1–3 years | 90 (7.6%) a | 189 (8.8%) a | ||

| 4–5 years | 39 (3.3%) a | 112 (5.2%) b | ||

| >5 years | 19 (1.6%) a | 67 (3.1%) b | ||

| Mean ± s.d./n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Medication use | ||

| Yes | 894 (26.9%) | |

| No | 2410 (72.6%) | |

| Missing | 15 (0.5%) | |

| Medication prescribed at the first visit | Yes | 419 (12.6%) |

| No | 2886 (86.9%) | |

| Missing | 15 (0.5%) | |

| Medication initiation session | 2.82 ± 2.189 (Min 1–Max 20, Median 2) | |

| Medication | ||

| Risperidone | 494 (55.3%) | |

| Hydroxyzine | 213 (23.8%) | |

| Methylphenidate | 107 (12.0%) | |

| Fluoxetine | 59 (6.6%) | |

| Atomoxetine | 16 (1.8%) | |

| Ecsitalopram | 6 (0.7%) | |

| Alprazolam | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Aripiprazole | 2 (0.2%) | |

| Melatonin | 2 (0.2%) | |

| Piracetam | 2 (0.2%) | |

| İmipramine | 1 (0.1%) | |

| Medication-related side effect, Yes | 34 (3.8%) | |

| Loss of appetite | 12 (35.3%) | |

| Drowsiness | 7 (20.6%) | |

| Insomnia | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Irritability | 3 (8.8%) | |

| Lethargy | 2 (5.9%) | |

| Nausea | 2 (5.9%) | |

| Enuresis | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Headache | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Rash | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Dark circles under the eyes | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Weight gain | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Hallucination | 1 (2.9%) | |

| Diagnosed | Undiagnosed | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± s.d. (Median)/n (%) | Mean ± s.d. (Median)/n (%) | |||

| Month of application | 47.6 ± 16.9 (48) | 45.3 ± 15.9 (45) | 0.000 m | |

| Clinical follow-up duration | 2.41 ± 1.466 (2) | 1.58 ± 0.861 (1) | 0.000 m | |

| At which consultation medication was prescribed | 2.9 ± 2.2 (2) | 2.6 ± 2.1 (2) | 0.354 m | |

| Medication prescribed at the first visit | 0.000 X2 | |||

| Yes | 341 (18.3%) | 77 (5.4%) | ||

| No | 1522 (81.7%) | 1359 (94.6%) | ||

| Missing | 7 | 6 | ||

| Medication usage | Yes | 741 39.8 | 152 10.6 | 0.000 X2 |

| No | 1122 60.2 | 1283 89.3 | ||

| Missing | 7 | 7 | ||

| Medication | ||||

| Risperidone | 422 (57%) | 71 (46.7%) | 0.021 X2 | |

| Hydroxyzine | 145 (19.6%) | 68 (44.7%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| Methylphenidate | 102 (13.8%) | 5 (3.3%) | 0.000 X2 | |

| Fluoxetine | 54 (7.3%) | 5 (3.3%) | 0.071 X2 | |

| Atomoxetine | 14 (1.9%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0.627 X2 | |

| Ecsitalopram | 5 (0.7%) | 1 (0.7%) | 1.000 X2 | |

| Alprazolam | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Aripiprazole | 2 (0.3%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Melatonin | 2 (0.3%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Piracetam | 2 (0.3%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| İmipramine | 1 (0.1%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Medication-related side effect, Yes | 28 (3.8%) | 6 (4%) | 0.895 X2 | |

| Drowsiness | 5 (17.9%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.334 X2 | |

| Loss of appetite | 11 (39.3%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.429 X2 | |

| Nausea | 1 (3.6%) | 1 (16.7%) | 0.308 X2 | |

| Enuresis | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.075 X2 | |

| Headache | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Rash | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Insomnia | 4 (14.3%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Dark circles under the eyes | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Irritability | 3 (10.7%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Weight gain | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Stagnation | 2 (7.1%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Hallucination | 1 (3.6%) | 0 | 1.000 X2 | |

| Variables | B | S.E. | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Age (month) | 0.026 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 1.026 | 1.020 | 1.033 |

| Father’s education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 0.001 | |||||

| Primary–secondary school | −0.083 | 0.392 | 0.832 | 0.920 | 0.427 | 1.983 |

| High school | −0.307 | 0.395 | 0.438 | 0.736 | 0.339 | 1.596 |

| University–college | −0.592 | 0.401 | 0.140 | 0.553 | 0.252 | 1.214 |

| Father’s mental illness (Yes) | 0.523 | 0.231 | 0.023 | 1.688 | 1.074 | 2.652 |

| Presenting complaints | ||||||

| Speech delay | 0.242 | 0.117 | 0.038 | 1.274 | 1.014 | 1.602 |

| Irritability | 0.455 | 0.111 | 0.000 | 1.576 | 1.269 | 1.959 |

| Hyperactivity | 1.226 | 0.116 | 0.000 | 3.408 | 2.717 | 4.275 |

| Lack of eye contact | 1.451 | 0.256 | 0.000 | 4.269 | 2.585 | 7.051 |

| Aggression | 0.423 | 0.185 | 0.022 | 1.526 | 1.062 | 2.194 |

| School refusal | 0.594 | 0.295 | 0.044 | 1.811 | 1.015 | 3.230 |

| Sleep problems | 1.066 | 0.253 | 0.000 | 2.903 | 1.767 | 4.770 |

| Fears | 0.645 | 0.270 | 0.017 | 1.906 | 1.123 | 3.237 |

| Difficulty separating from mother | 0.649 | 0.366 | 0.076 | 1.914 | 0.934 | 3.923 |

| Constant | 0.770 | 0.405 | 0.057 | 2.159 | ||

| Variables | B | S.E. | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for EXP(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex (Male) | 0.157 | 0.119 | 0.189 | 1.170 | 0.926 | 1.477 |

| Age (month) | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 1.012 | 1.004 | 1.019 |

| Mother’s education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 0.650 | |||||

| Primary–secondary school | 0.198 | 0.354 | 0.575 | 1.220 | 0.609 | 2.441 |

| High school | 0.177 | 0.370 | 0.633 | 1.193 | 0.578 | 2.462 |

| University–college | −0.007 | 0.391 | 0.986 | 0.993 | 0.462 | 2.136 |

| Mother’s mental illness (Yes) | −0.077 | 0.183 | 0.673 | 0.926 | 0.647 | 1.324 |

| Father’s education | ||||||

| Illiterate | 0.406 | |||||

| Primary–secondary school | 0.160 | 0.473 | 0.736 | 1.173 | 0.464 | |

| High school | 0.057 | 0.485 | 0.907 | 1.059 | 0.409 | |

| University–college | −0.139 | 0.500 | 0.780 | 0.870 | 0.327 | |

| Father’s mental illness (Yes) | 0.684 | 0.267 | 0.010 | 1.982 | 1.175 | 3.344 |

| Diagnoses | ||||||

| Stuttering | 0.138 | 0.233 | 0.555 | 1.147 | 0.726 | |

| Mental retardation | 0.585 | 0.174 | 0.001 | 1.795 | 1.276 | 2.526 |

| Behavioral disorder | 3.091 | 0.287 | 0.000 | 22.002 | 12.529 | 38.636 |

| ADHD | 2.790 | 0.176 | 0.000 | 16.288 | 11.536 | 22.999 |

| Reactive attachment disorder | 1.453 | 0.235 | 0.000 | 4.274 | 2.697 | |

| Externalizing disorder | −0.090 | 0.314 | 0.775 | 0.914 | 0.494 | |

| ASD | 2.269 | 0.205 | 0.000 | 9.671 | 6.472 | 14.451 |

| Sleep disorder | 2.868 | 0.447 | 0.000 | 17.603 | 7.327 | 42.292 |

| Anxiety disorders | 2.421 | 0.203 | 0.000 | 11.253 | 7.556 | |

| Speech disorder | −0.742 | 0.303 | 0.014 | 0.476 | 0.263 | 0.862 |

| Childhood masturbation | −0.970 | 1.027 | 0.345 | 0.379 | 0.051 | 2.834 |

| Adjustment disorder and depression | 1.530 | 0.573 | 0.008 | 4.619 | 1.502 | 14.205 |

| Tic disorder | 0.289 | 0.617 | 0.640 | 1.334 | 0.398 | |

| Constant | 5.641 | 1.026 | 0.000 | 281.688 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bozatlı, L.; Aykutlu, H.C.; Uğurtay Dayan, C.; Ataş, T.; Arslan, E.N.; Gündüz Gül, Y.Ö.; Görker, I. Clinical Profiles and Medication Predictors in Early Childhood Psychiatric Referrals: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061038

Bozatlı L, Aykutlu HC, Uğurtay Dayan C, Ataş T, Arslan EN, Gündüz Gül YÖ, Görker I. Clinical Profiles and Medication Predictors in Early Childhood Psychiatric Referrals: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(6):1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061038

Chicago/Turabian StyleBozatlı, Leyla, Hasan Cem Aykutlu, Cansu Uğurtay Dayan, Tuğçe Ataş, Esra Nisa Arslan, Yeşim Özge Gündüz Gül, and Işık Görker. 2025. "Clinical Profiles and Medication Predictors in Early Childhood Psychiatric Referrals: A 10-Year Retrospective Study" Medicina 61, no. 6: 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061038

APA StyleBozatlı, L., Aykutlu, H. C., Uğurtay Dayan, C., Ataş, T., Arslan, E. N., Gündüz Gül, Y. Ö., & Görker, I. (2025). Clinical Profiles and Medication Predictors in Early Childhood Psychiatric Referrals: A 10-Year Retrospective Study. Medicina, 61(6), 1038. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61061038