Psychometric Properties of the Improved Report of Oslo Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries (OSTRC-O2) and Health Problems (OSTRC-H2)

Abstract

1. Introduction

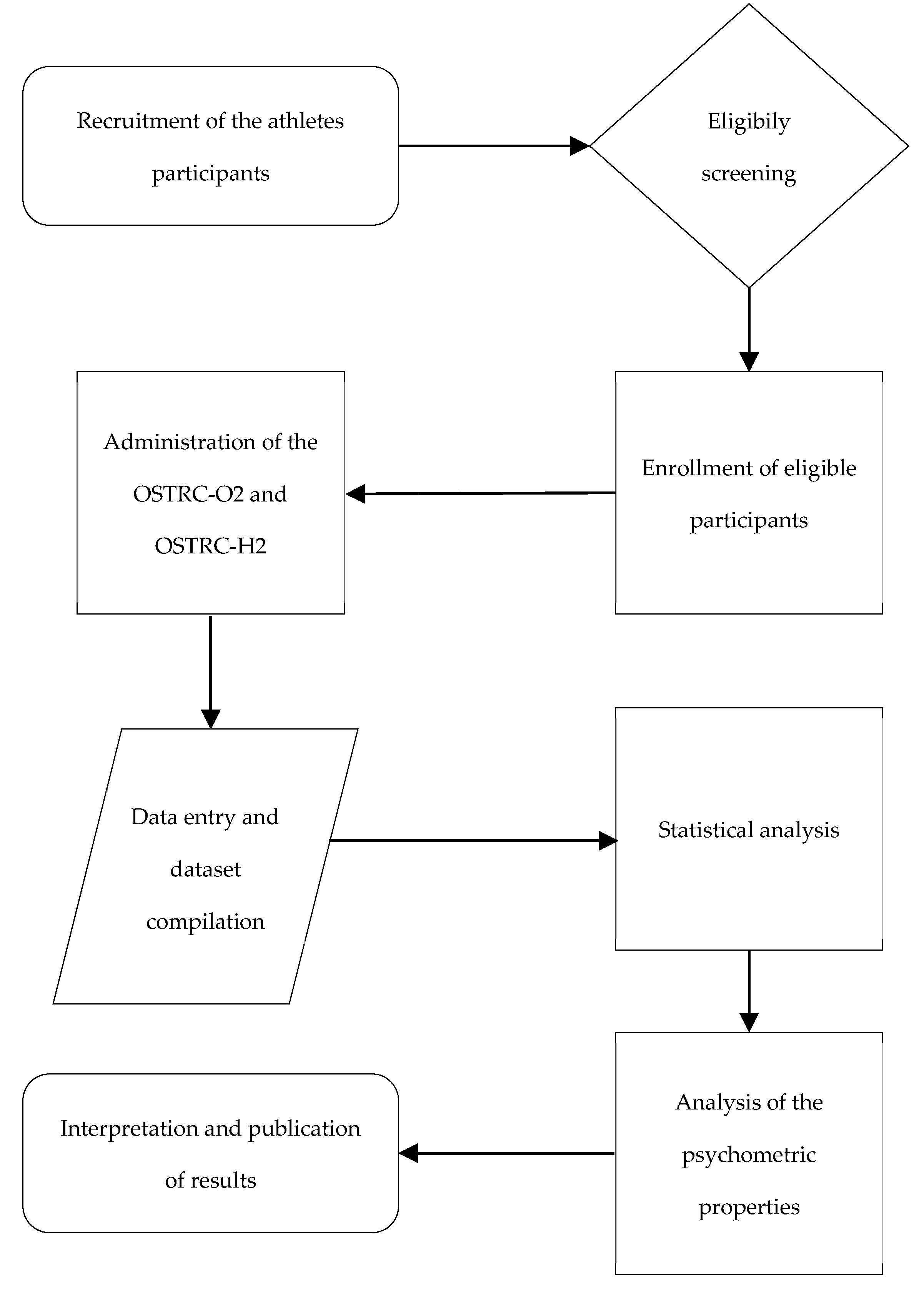

2. Materials and Methods

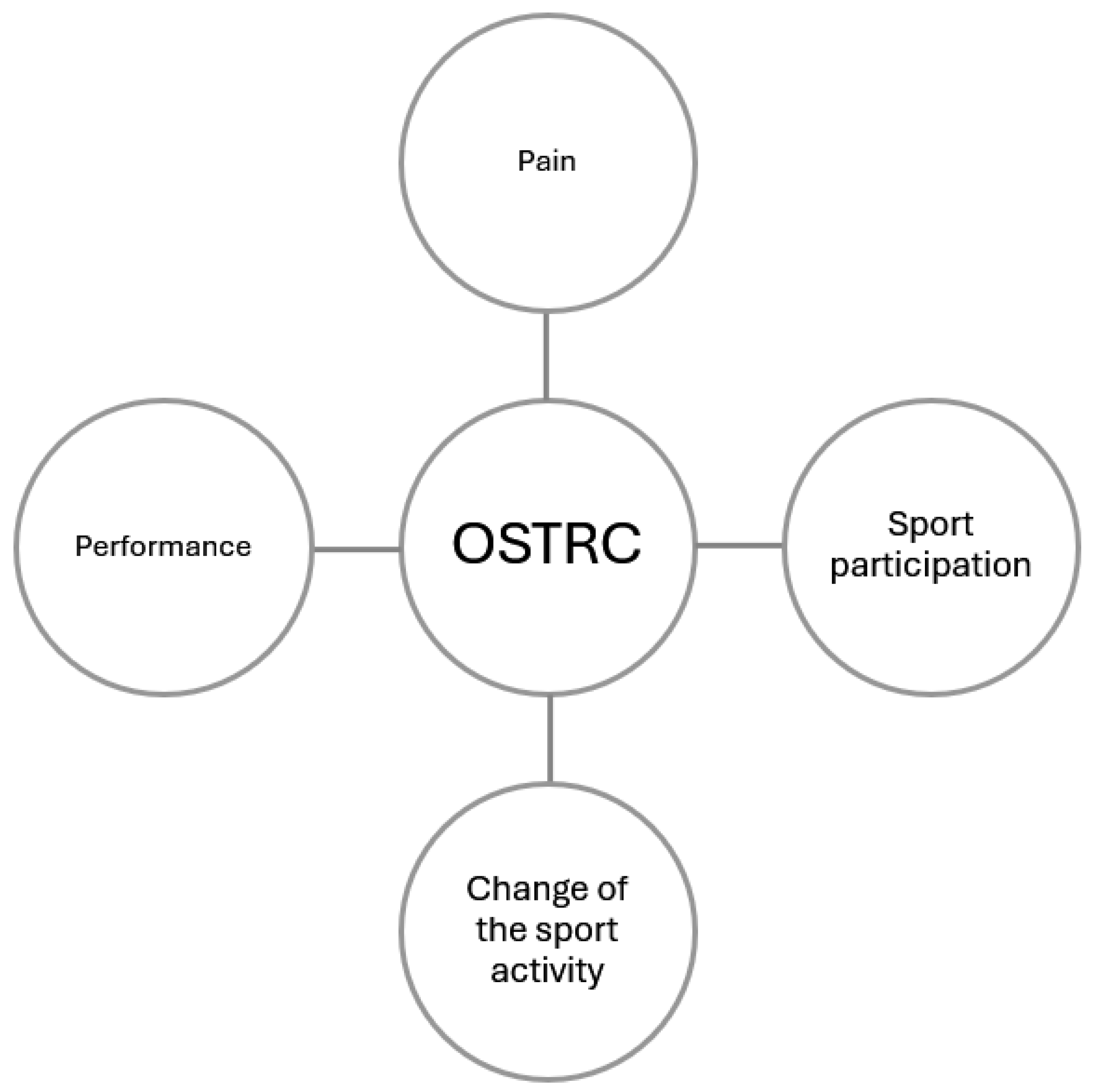

2.1. Intruments

2.2. Participants

- Age over 18 years

- Practicing sport at a competitive or non-competitive level for at least one year

- To have suffered of at least one injury during sport

2.3. Internal Consistency and Reliability

2.4. Construct Validity

2.5. Cross-Cultural Validity

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Internal Consistency

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Construct Validity

3.5. Cross-Cultural Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Internal Consistency

4.2. Reliability

4.3. Construct Validity

4.4. Cross-Cultural Validity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Toft, B.S.; Uhrenfeldt, L. The lived experiences of being physically active when morbidly obese: A qualitative systematic review. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2015, 10, 28577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimani, A.; Aboagye, E.; Kwak, L. The effectiveness of workplace nutrition and physical activity interventions in improving productivity, work performance and workability: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schley, S.; Buser, A.; Render, A.; Ramirez, M.E.; Truong, C.; Easley, K.A.; Shenvi, N.; Jayanthi, N. A Risk Tool for Evaluating Overuse Injury and Return-to-Play Time Periods in Youth and Collegiate Athletes: Preliminary Study. Sports Health 2024, 17, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewal, P.H.; Putrino, D.; Norman, M.R. Burnout and Motivation in Sport. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2021, 44, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarsen, B.; Myklebust, G.; Bahr, R. Development and validation of a new method for the registration of overuse injuries in sports injury epidemiology: The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) Overuse Injury Questionnaire. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschmüller, A.; Steffen, K.; Fassbender, K.; Clarsen, B.; Leonhard, R.; Konstantinidis, L.; Südkamp, N.P.; Kubosch, E.J. German translation and content validation of the OSTRC Questionnaire on overuse injuries and health problems. Br. J. Sports Med. 2017, 51, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Cal, J.; Molina-Torres, G.; Carrasco-Vega, E.; Barni, L.; Ventura-Miranda, M.I.; Gonzalez-Sanchez, M. Spanish Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre (OSTRC) Overuse Injury Questionnaire in Handball Players. Healthcare 2023, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaewkul, K.; Chaijenkij, K.; Tongsai, S. Validity and Reliability of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center (OSTRC) Questionnaire on Overuse Injury and Health Problem in Thai Version. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2021, 104, 105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, J.E.; Rathleff, C.R.; Rathleff, M.S.; Andreasen, J. Danish translation and validation of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre questionnaires on overuse injuries and health problems. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2016, 26, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, E.; Frohm, A.; Ek, P.; Hagberg, J.; Wirén, C.; Heijne, A. Swedish translation and validation of a web-based questionnaire for registration of overuse problems. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, R.M.; Hespanhol, L.; Lopes, A.D. Brazilian version of the OSTRC Questionnaire on health problems (OSTRC-BR): Translation, cross-cultural adaptation and measurement properties. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021, 25, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimo, S.; Yoshida, N.; Hogan, T.; Takegami, A.; Hirono, J.; Matsuki, Y.; Hagiwara, M.; Nagano, Y. Japanese translation and validation of web-based questionnaires on overuse injuries and health problems. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretto, S.; Bertini, P.; Plebani, G.; Maremmani, D.; Napoli, R. Italian Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Improved Report of Oslo Sports Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries and Health Problems. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2023, 13, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarsen, B.; Bahr, R.; Myklebust, G.; Andersson, S.H.; Docking, S.I.; Drew, M.; Finch, C.F.; Fortington, L.V.; Harøy, J.; Khan, K.M.; et al. Improved reporting of overuse injuries and health problems in sport: An update of the Oslo Sport Trauma Research Center questionnaires. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashimo, S.; Yoshida, N.; Hogan, T.; Takegami, A.; Nishida, S.; Nagano, Y. An update of the Japanese Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center questionnaires on overuse injuries and health problems. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailón-Cerezo, J.; Clarsen, B.; Sánchez-Sánchez, B.; Torres-Lacomba, M. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center Questionnaires on Overuse Injury and Health Problems (2nd Version) in Spanish Youth Sports. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2020, 8, 2325967120968552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drole, K.; Steffen, K.; Paravlic, A. Slovenian Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of the Updated Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center Questionnaire on Health Problems (OSTRC-H2). Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2024, 12, 23259671241287767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Galvanin, M.; Hauspy, R.; Clarsen, B.M.; Demoulin, C.; Bornheim, S.; Van Beveren, J.; Kaux, J.-F. French Translation and Validation of the OSTRC-H2 Questionnaire on Overuse Injuries and Health Problems in Elite Athletes. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2023, 11, 23259671231173374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruchinho, P.; López-Franco, M.D.; Capelas, M.L.; Almeida, S.; Bennett, P.M.; da Silva, M.M.; Teixeira, G.; Nunes, E.; Lucas, P.; Gaspar, F. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Validation of Measurement Instruments: A Practical Guideline for Novice Researchers. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 2701–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquez, M.A.; Speroni, A.; Galeoto, G.; Ruotolo, I.; Sellitto, G.; Tofani, M.; Gonzàlez-Bernal, J.; Berardi, A. The Moorong Self Efficacy Scale: Translation, cultural adaptation, and validation in Italian; cross sectional study, in people with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord Ser. Cases 2022, 8, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, J.D.; Piva, S.R.; Fritz, J.M. Responsiveness of the Numeric Pain Rating Scale in Patients with Low Back Pain. Spine 2005, 30, 1331–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodraliu, G.; Mosconi, P.; Groth, N.; Carmosino, G.; Perilli, A.; Gianicolo, E.A.; Rossi, C.; Apolone, G. Subjective health status assessment: Evaluation of the Italian version of the SF-12 Health Survey. Results from the MiOS Project. J. Epidemiol. Biostat. 2001, 6, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthoine, E.; Moret, L.; Regnault, A.; Sébille, V.; Hardouin, J.B. Sample size used to validate a scale: A review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flake, J.K.; Davidson, I.J.; Wong, O.; Pek, J. Construct validity and the validity of replication studies: A systematic review. Am. Psychol. 2022, 77, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Bouter, L.; De Vet, H.C.; Terwee, C.B. Protocol of the COSMIN study: COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2006, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Prinsen, C.A.C.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Terwee, C.B. The COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) and how to select an outcome measurement instrument. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, P.; Wong, J.J.; Sutton, D.; Shearer, H.M.; Mior, S.; Randhawa, K.; Ameis, A.; Carroll, L.J.; Nordin, M.; Yu, H.; et al. Management of neck pain and associated disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur. Spine J. 2016, 25, 2000–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population N° 102 | |

|---|---|

| Female N (%) | 15 (14.7) |

| Hours of activity per week N (%) | |

| 1 (0–8 h) | 13 (12.7) |

| 2 (10–17 h) | 51 (50) |

| 3 (18–28 h) | 38 (37.3) |

| Mean activity hours ± DS | 14.67 ± 5.907 |

| Age N (%) | |

| 1.0 (18–22 years) | 24 (23.5) |

| 2.0 (23–27 years) | 48 (47.1) |

| 3.0 (28–32 years) | 17 (16.7) |

| 4.0 (over 33 years) | 13 (12.7) |

| Mean age ± DS | 26.44 ± 6.425 |

| Sport N (%) | |

| Climbing | 1 (1) |

| Athletics | 1 (1) |

| Basket | 17 (16.7) |

| Box | 1 (1) |

| Soccer | 47 (46.1) |

| Five-a-side soccer | 4 (3.9) |

| Cross Fit | 1 (1) |

| American Football | 1 (1) |

| Kite Surf | 1 (1) |

| Padel | 4 (3.9) |

| Swimming ball | 1 (1) |

| Volleyball | 8 (7.8) |

| Speed skating | 7 (6.9) |

| Power Lifting | 3 (2.9) |

| Rugby | 2 (2) |

| Tennis | 3 (2.9) |

| Acute pain N (%) | |

| No acute pain | 76 (74.5) |

| Ankle | 4 (3.9) |

| Calf | 3 (2.9) |

| Foot | 1 (1) |

| Hand | 1 (1) |

| Hip | 1 (1) |

| Knee | 5 (4.9) |

| Low back pain | 2 (2) |

| Neck | 1 (1) |

| Shoulder | 1 (1) |

| Thigh | 6 (5.9) |

| Trunk | 1 (1) |

| PERSISTENT pain N (%) | |

| No persistent pain | 19 (18.6) |

| Ankle | 13 (12.7) |

| Arm | 1 (1) |

| Calf | 1 (1) |

| Elbow | 2 (2) |

| Groin | 7 (6.9) |

| Hip | 5 (4.9) |

| Knee | 28 (27.5) |

| Lbp | 7 (6.9) |

| Shin | 2 (2) |

| Shoulder | 11 (10.9) |

| Thigh | 5 (4.9) |

| Wrist | 1 (1) |

| OSTRC-O2 OSTRC-H2 | Medium Scale If the Element Is Deleted | Scale Variance If the Element Is Deleted | Correlation Element—Total Corrected | Correlation Multiple Quadratic | Cronbach’s Alpha If the Element Is Deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 35.32 | 634.162 | 0.864 | 0.753 | 0.933 |

| Q2 | 34.71 | 570.586 | 0.872 | 0.764 | 0.930 |

| Q3 | 34.49 | 583.837 | 0.872 | 0.767 | 0.929 |

| Q4 | 35.22 | 590.507 | 0.881 | 0.782 | 0.926 |

| Item | Test | Retest | ICC | Confidence Interval 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± DS | Mean ± DS | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||

| OSTRC-O2 | 1 | 11.25 ± 7.872 | 12.09 ± 7.703 | 0.740 | 0.637 | 0.816 |

| 2 | 11.87 ± 9.203 | 12.43 ± 8.620 | 0.726 | 0.620 | 0.806 | |

| 3 | 12.09 ± 8.907 | 12.41 ± 8.620 | 0.800 | 0.718 | 0.861 | |

| 4 | 11.36 ± 8.701 | 11.57 ± 8.411 | 0.746 | 0.646 | 0.821 | |

| TOT | 46.58 ± 32.229 | 48.50 ± 31.007 | 0.705 | 0.854 | 8.562 | |

| OSTRC-H2 | 1 | 11.25 ± 7.872 | 12.09 ± 7.703 | 0.740 | 0.637 | 0.816 |

| 2 | 11.87 ± 9.203 | 12.43 ± 8.620 | 0.726 | 0.620 | 0.806 | |

| 3 | 12.09 ± 8.907 | 12.41 ± 8.620 | 0.800 | 0.718 | 0.861 | |

| 4 | 11.36 ± 8.701 | 11.57 ± 8.411 | 0.746 | 0.646 | 0.821 | |

| TOT | 46.58 ± 32.229 | 48.50 ± 31.007 | 0.705 | 0.854 | 8.562 | |

| SF-12 PCS | SF-12 MCS | NPRS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OSTRC-O2 | −0.322 ** | −0.055 | 0.339 ** |

| OSTRC-H2 | −0.322 ** | −0.055 | 0.339 ** |

| Mean ± DS OSTRC-O2 OSTRC-H2 | Test | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 45.90 ± 31.985 | −0.513 | 0.609 |

| Male | 50.53 ± 34.488 | ||

| Hours of activity | |||

| 1 (0–8 h) | 52.62 ± 33.306 | 0.262 | 0.770 |

| 2 (10–17 h) | 45.41 ± 31.292 | ||

| 3 (18–28 h) | 46.08 ± 33.726 | ||

| Age | |||

| 1.0 (18–22 years) | 43.50 ± 33.905 | 0.249 | 0.862 |

| 2.0 (23–27 years) | 49.17 ± 31.968 | ||

| 3.0 (28–32 years) | 42.88 ± 32.913 | ||

| 4.0 (over 33 years) | 47.54 ± 32.033 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leonardi, G.; Galeoto, G.; Maselli, F.; Napoli, R.; Favaretto, S.; Tomassini, M.; Plebani, G.; Carraro, L.; Angilecchia, D. Psychometric Properties of the Improved Report of Oslo Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries (OSTRC-O2) and Health Problems (OSTRC-H2). Medicina 2025, 61, 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050935

Leonardi G, Galeoto G, Maselli F, Napoli R, Favaretto S, Tomassini M, Plebani G, Carraro L, Angilecchia D. Psychometric Properties of the Improved Report of Oslo Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries (OSTRC-O2) and Health Problems (OSTRC-H2). Medicina. 2025; 61(5):935. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050935

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeonardi, Giulio, Giovanni Galeoto, Filippo Maselli, Roberto Napoli, Simone Favaretto, Martina Tomassini, Giuseppe Plebani, Lorenzo Carraro, and Domenico Angilecchia. 2025. "Psychometric Properties of the Improved Report of Oslo Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries (OSTRC-O2) and Health Problems (OSTRC-H2)" Medicina 61, no. 5: 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050935

APA StyleLeonardi, G., Galeoto, G., Maselli, F., Napoli, R., Favaretto, S., Tomassini, M., Plebani, G., Carraro, L., & Angilecchia, D. (2025). Psychometric Properties of the Improved Report of Oslo Trauma Research Centre Questionnaires on Overuse Injuries (OSTRC-O2) and Health Problems (OSTRC-H2). Medicina, 61(5), 935. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050935