Evaluation of Spousal Support and Stress Coping Styles of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Fetal Anomaly

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Scales Used in This Study

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Data Form

3.2. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI)

3.3. Spousal Support Scale (SSS)

3.4. Coping Styles Scale (CSS)

3.5. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DeSilva, M.; Munoz, F.M.; Mcmillan, M.; Kawai, A.T.; Marshall, H.; Macartney, K.K.; Joshi, J.; Oneko, M.; Rose, A.E.; Dolk, H.; et al. Congenital anomalies: Case definition and guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine 2016, 34, 6015–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahya, R.H.; Roman, A.; Grant, S.; Whitehead, C.L. Antenatal screening for fetal structural anomalies—Routine or targeted practice? Best. Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2024, 96, 102521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulgheroff, F.F.; Peixoto, A.B.; Petrini, C.G.; Caldas, T.M.R.D.C.; Ramos, D.R.; Magalhães, F.O.; Araujo Júnior, E. Fetal structural anomalies diagnosed during the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy using ultrasonography: A retrospective cohort study. Sao Paulo Med. J. Rev. Paul. Med. 2019, 137, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomon, L.J.; Alfirevic, Z.; Berghella, V.; Bilardo, C.; Hernandez-Andrade, E.; Johnsen, S.L.; Kalache, K.; Leung, K.Y.; Malinger, G.; Munoz, H.; et al. Practice guidelines for performance of the routine mid-trimester fetal ultrasound scan. Ultrasound. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 37, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrell, A.; Robinson, J.N.; Santolaya-Forgas, J. Clinical value of the 11- to 13+6-week sonogram for detection of congenital malformations: A review. Am. J. Perinatol. 2011, 28, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyar, A.; Acar, D.K.; Turhan, U.; Gedik Özköse, Z.; Ekiz, A.; Gezdirici, A.; Yılmaz Güleç, E.; Polat, İ. Late terminations of pregnancy due to fetal abnormalities: An analysis of 229 cases. IKSST Derg. 2018, 10, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Wu, Y.; Kapse, K.; Vozar, T.; Cheng, J.J.; Murnick, J.; Henderson, D.; Teramoto, H.; Limperopoulos, C.; Andescavage, N. Prenatal Maternal Psychological Distress During the COVID-19 Pandemic and Newborn Brain Development. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2417924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenn, J.; Strothom, H. Psychosocial aspect of prenatal screening and diagnosis. In The Troubled Helix: Social and Psychological Implications of the New Human Genetics; Marteau, T., Richards, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1999; pp. 140–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bekkhus, M.; Oftedal, A.; Braithwaite, E.; Haugen, G.; Kaasen, A. Paternal Psychological Stress After Detection of Fetal Anomaly During Pregnancy. A Prospective Longitudinal Observational Study. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algorani, E.B.; Gupta, V. Coping Mechanisms. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Berjot, S.; Gillet, N. Stress and coping with discrimination and stigmatization. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öner, H.; Karabudak, S.S. Negative emotions and coping experiences of nursing students during clinical practices: A focus group interview. J. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, 12, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, E.; Yetim, A. Coping with stress and self-confidence in athletes: A review. J. Theory Pract. Sport. 2023, 2, 46–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Sun, Y.; Qian, J.; Tian, Y.; Wang, F.; Yu, Q.; Yu, X. Parents’ experiences and need for social support after pregnancy termination for fetal anomaly: A qualitative study in China. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, K.L.; Oxlad, M.; Due, C.; Middleton, P. Factors contributing to men’s grief following pregnancy loss and neonatal death: Further development of an emerging model in an Australian sample. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statham, H.; Solomou, W.; Chitty, L. Prenatal diagnosis of fetal abnormality: Psychological effects on women in low-risk pregnancies. Baillieres Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2000, 14, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slade, L.; Obst, K.; Deussen, A.; Dodd, J. The tools used to assess psychological symptoms in women and their partners after termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly: A scoping review. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2023, 288, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landolt, S.A.; Weitkamp, K.; Roth, M.; Sisson, N.M.; Bodenmann, G. Dyadic coping and mental health in couples: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 106, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinapoli, L.; Colloca, G.; Di Capua, B.; Valentini, V. Psychological Aspects to Consider in Breast Cancer Diagnosis and Treatment. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2021, 23, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasen, A.; Helbig, A.; Malt, U.F.; Næs, T.; Skari, H.; Haugen, G. Maternal psychological responses during pregnancy after ultrasonographic detection of structural fetal anomalies: A prospective longitudinal observational study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syngelaki, A.; Hammami, A.; Bower, S.; Zidere, V.; Akolekar, R.; Nicolaides, K.H. Diagnosis of fetal non-chromosomal abnormalities on routine ultrasound examination at 11–13 weeks’ gestation. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 54, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, M.; Şahin, N.; Erkmen, H. Turkish version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory: Psychometric properties. J. Cogn. Psychother. 1998, 12, 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, İ. Eş destek ölçeğinin geliştirilmesi. Psikolojik Danışma Rehb. Derg. 2004, 3, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Şahin, N.H.; Durak, A. Stresle başaçıkma tarzları ölçeği: Üniversite öğrencileri için uyarlanması. Türk Psikol. Derg. 1995, 10, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1980, 21, 219–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hisli, N. Beck depresyon ölçeğinin bir Türk örnekleminde geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. Psikoloji Dergisi 1988, 6, 118–122. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, Z.N.; Langaker, M.D. Physiology, Pregnancy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mahrer, N.E.; Ramos, I.F.; Guardino, C.; Davis, E.P.; Ramey, S.L.; Shalowitz, M.; Schetter, C.D. Pregnancy anxiety in expectant mothers predicts offspring negative affect: The moderating role of acculturation. Early Hum. Dev. 2020, 141, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oftedal, A.; Bekkhus, M.; Haugen, G.; Hjemdal, O.; Czajkowski, N.O.; Kaasen, A. Long-Term Impact of Diagnosed Fetal Anomaly on Parental Traumatic Stress, Resilience, and Relationship Satisfaction. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 48, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aite, L.; Zaccara, A.; Mirante, N.; Nahom, A.; Trucchi, A.; Capolupo, I.; Bagolan, P. Antenatal diagnosis of congenital anomaly: A really traumatic experience? J. Perinatol. 2011, 31, 760–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasen, A.; Helbig, A.; Malt, U.F.; Naes, T.; Skari, H.; Haugen, G.N. Paternal psychological response after ultrasonographic detection of structural fetal anomalies with a comparison to maternal response: A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2013, 13, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenromp, M.J.; Christiaens, G.C.; Van den Bout, J.; Mulder, E.J.; Hunfeld, J.A.; Bilardo, C.M.; Offermans, J.P.; Visser, G.H. Long-term psychological consequences of pregnancy termination for fetal abnormality: A cross-sectional study. Prenat. Diagn. 2005, 25, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theroux, R.; Hersperger, C.L. Managing broken expectations after a diagnosis of fetal anomaly. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, C.L.; Byrne, J.J.; Nelson, D.B.; Schell, R.C.; Dashe, J.S. Postpartum Depression Risk following Prenatal Diagnosis of Major Fetal Structural Anomalies. Am. J. Perinatol. 2022, 39, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaydırak, M.M.; Balkan, E.; Bacak, N.; Kızoglu, F. Perceived Social Support and Depression, Anxiety and Stress in Pregnant Women Diagnosed With Foetal Anomaly. J. Adv. Nurs. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Gong, W.; Taylor, B.; Cai, Y.; Xu, D.R. Coping Styles in Pregnancy, Their Demographic and Psychological Influences, and Their Association with Postpartum Depression: A Longitudinal Study of Women in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Bista, A.P. Perceived stress and coping strategies among pregnant women at a tertiary hospital, Bharatpur. J. Nurs. Educ. Nepal. 2023, 14, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiyak, S. The relationship of depression, anxiety, and stress with pregnancy symptoms and coping styles in pregnant women: A multi-group structural equation modeling analysis. Midwifery 2024, 136, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irani, M.; Khadivzadeh, T.; Asghari-Nekah, S.M.; Ebrahimipour, H. Coping Strategies of Pregnant Women with Detected Fetal Anomalies in Iran: A Qualitative Study. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2019, 24, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, W.T.; He, Q.; Li, Y.; Peng, H.; Xie, J.; Hu, H.; Qin, C. Coping strategies following the diagnosis of a fetal anomaly: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1055562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mutawtah, M.; Campbell, E.; Kubis, H.P.; Erjavec, M. Women’s experiences of social support during pregnancy: A qualitative systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadpour, P.; Curry, C.; Jahanfar, S.; Nikanfar, R.; Mirghafourvand, M. Family and spousal support are associated with higher levels of maternal functioning in a study of Iranian postpartum women. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoniou, E.; Tzanoulinou, M.D.; Stamoulou, P.; Orovou, E. The important role of partner support in women’s mental disorders during the perinatal period: A literature review. Maedica 2022, 17, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hekmat, K.; Kamali, F.; Abedi, P.; Afshari, P. Explaining mothers’ experiences of performing fetal health screening tests in the first trimester of pregnancy: A qualitative study with content analysis approach. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2023, 18, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirtabar, S.M.; Pahlavan, Z.; Aligoltabar, S.; Barat, S.; Nasiri-Amiri, F.; Nikpour, M.; Behmanesh, F.; Taheri, S.; Nasri, K.; Faramarzi, M. Women’s worries about prenatal screening tests suspected of fetal anomalies: A qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 2023, 23, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cases (n = 59) | Controls (n = 98) | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Age, mean ± SD | 29.5 ± 5.5 | 29.1 ± 4.9 | 0.587 * | |||

| Marital status | Single | 57 | 96,6 | 98 | 100.0 | 0.140 ** |

| Married | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Education level | High school or below | 46 | 78.0 | 54 | 55.1 | 0.004 ** |

| University | 13 | 22.0 | 44 | 44.9 | ||

| Residence | Countryside | 9 | 15.3 | 31 | 31.6 | 0.023 ** |

| City | 50 | 84.7 | 67 | 68.4 | ||

| Financial situation | Low | 3 | 5.1 | 7 | 7.1 | 0.911 ** |

| Moderate | 54 | 91.5 | 88 | 89.8 | ||

| High | 2 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.1 | ||

| Working status | Working | 14 | 23.7 | 28 | 28.6 | 0.507 ** |

| Not working | 45 | 76.3 | 70 | 71.4 | ||

| Smoking | Yes | 11 | 18.6 | 15 | 15.3 | 0.586 ** |

| No | 48 | 81.4 | 83 | 84.7 | ||

| Specialty in the history of the patient | Yes | 1 | 1.7 | 3 | 3.1 | 0.599 ** |

| No | 58 | 98.3 | 95 | 96.9 | ||

| Specialty in the history of the patient’s family | Yes | 2 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.1 | 0.910 ** |

| No | 57 | 96.6 | 95 | 96.9 | ||

| Consanguineous marriage | Yes | 12 | 20.3 | 11 | 11.2 | 0.118 ** |

| No | 47 | 79.7 | 87 | 88.8 | ||

| Gravidity, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–3.0) | 0.075 *** | |||

| Parity, median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–1.0) | 0.075 *** | |||

| Obstetric visits | Regular | 56 | 94.9 | 98 | 100.0 | 0.051 ** |

| Irregular | 3 | 5.1 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| History of fetal anomaly in previous pregnancies | Yes | 6 | 10.2 | 2 | 2.0 | 0.053 ** |

| No | 53 | 89.8 | 96 | 98.0 | ||

| Type of conception | Spontaneous | 57 | 96.6 | 98 | 100.0 | 0.140 ** |

| IVF | 2 | 3.4 | 0 | 0.0 | ||

| Gestational age at which fetal anomaly was detected (weeks) | 0–12 weeks | 6 | 10.2 | - | ||

| 12–18 weeks | 13 | 22.0 | ||||

| 19–24 weeks | 29 | 49.2 | ||||

| >24 weeks | 11 | 18.6 | ||||

| Number of detected anomalies | 1 | 44 | 74.6 | - | - | |

| 2 | 8 | 13.6 | ||||

| >2 | 7 | 11.9 | ||||

| Currently disabled child | Yes | 3 | 5.1 | - | - | |

| No | 56 | 94.9 | ||||

| The patient’s thoughts on how the anomaly will affect the baby | Physical | 23 | 40.4 | - | - | |

| Mental | 10 | 17.5 | ||||

| Physical + Mental | 24 | 42.1 | ||||

| Spousal Support Scale, median (IQR) | 77.0 (67.0–81.0) | 77.5 (74.0–80.0) | 0.263 *** | |||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory, median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–12.0) | 3.0 (1.0–7.0) | <0.001 *** | |||

| Beck Depression Inventory, median (IQR) | 8.0 (4.0–11.0) | 6.0 (4.0–10.0) | 0.122 *** | |||

| Self-Confident Approach, median (IQR) | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) | 0.796 *** | |||

| Seeking Social Support, median (IQR) | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 8.0 (7.0–9.0) | 0.270 *** | |||

| Optimistic Approach, median (IQR) | 10.0 (8.0–12.0) | 10.0 (8.0–12.0) | 0.460 *** | |||

| Helpless Approach, median (IQR) | 9.0 (7.0–12.0) | 8.0 (5.0–12.0) | 0.218 *** | |||

| Submissive Approach, median (IQR) | 8.0 (5.0–10.0) | 6.0 (4.0–8.0) | 0.004 *** | |||

| B | S.E. | p | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education Level (Ref = University) | 1.177 | 0.477 | 0.014 | 3.243 (1.274–8.254) |

| Residence (Ref = Countryside) | 1.117 | 0.526 | 0.034 | 3.054 (1.090–8.560) |

| Gestational Age (Ref = 2. Trimester) | −22.207 | 0.857 | 0.998 | 0.000 (0.000–) |

| Submissive Approach | 0.078 | 0.057 | 0.170 | 1.081 (0.967–1.209) |

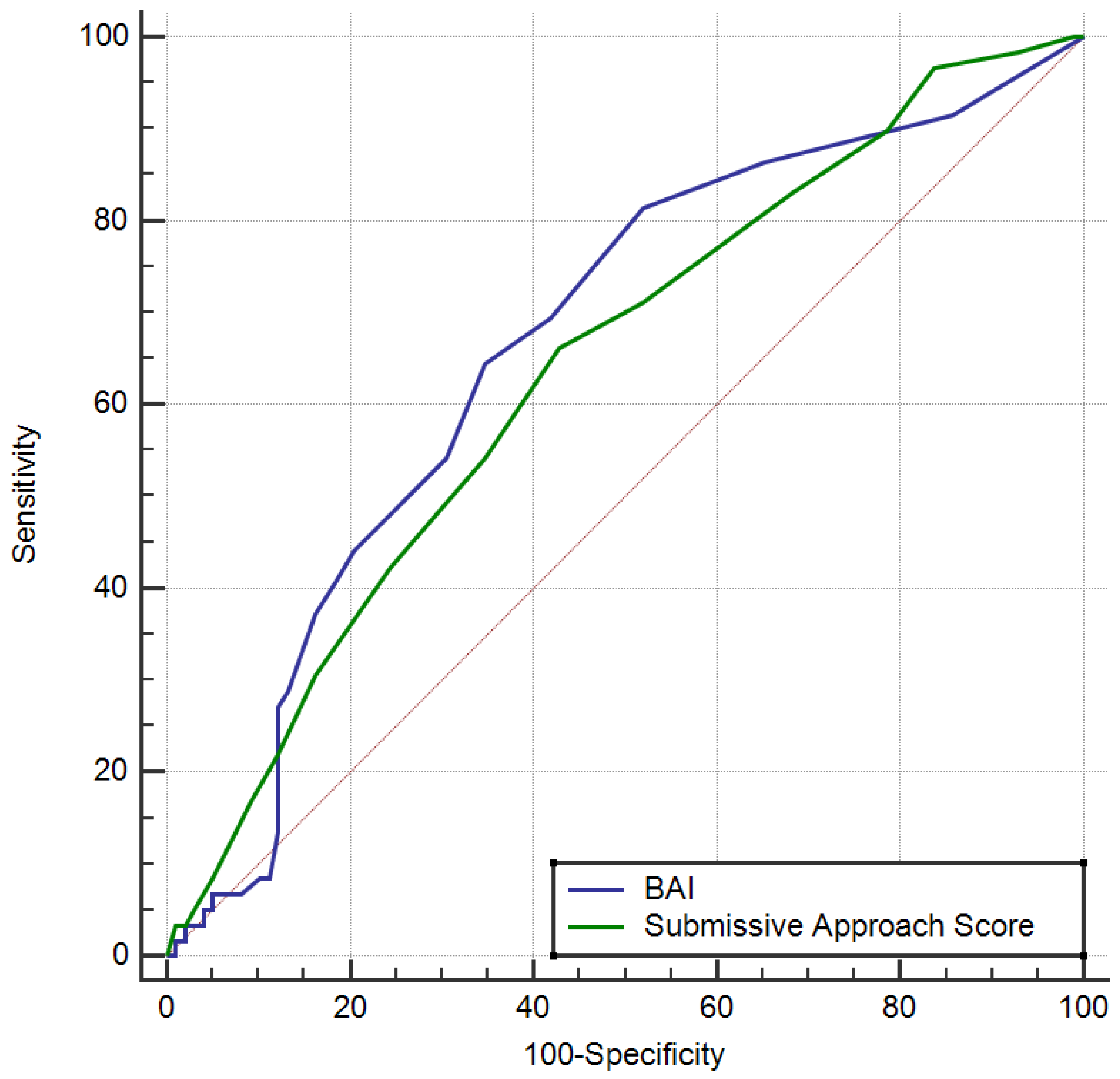

| Space | p | 95% Confidence Interval | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |||||||

| Beck Anxiety Inventory > 4 | 0.665 | <0.001 | 0.586 | 0.739 | 64.4 | 65.3 | 52.8 | 75.3 |

| Submissive Approach > 6 | 0.637 | 0.002 | 0.557 | 0.713 | 66.1 | 57.1 | 48.1 | 73.7 |

| Spousal Support Scale | BAI | BDI | Self-Confident Approach | Seeking Social Support | Optimistic Approach | Helpless Approach | Submissive Approach | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | r | −0.187 | |||||||

| p | 0.157 | ||||||||

| Beck Depression Inventory | r | −0.409 | 0.366 | ||||||

| p | 0.001 | 0.005 | |||||||

| Self- Confident Approach | r | 0.200 | −0.289 | −0.308 | |||||

| p | 0.128 | 0.026 | 0.019 | ||||||

| Seeking Social Support | r | 0.124 | −0.261 | −0.246 | 0.219 | ||||

| p | 0.350 | 0.046 | 0.063 | 0.096 | |||||

| Optimistic Approach | r | 0.186 | −0.295 | −0.309 | 0.630 | −0.053 | |||

| p | 0.159 | 0.023 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.688 | ||||

| Helpless Approach | r | −0.178 | 0.178 | 0.311 | 0.052 | −0.199 | 0.055 | ||

| p | 0.177 | 0.178 | 0.017 | 0.694 | 0.131 | 0.679 | |||

| Submissive Approach | r | −0.020 | 0.073 | −0.048 | 0.211 | 0.012 | 0.278 | 0.423 | |

| p | 0.881 | 0.584 | 0.723 | 0.108 | 0.931 | 0.033 | 0.001 | ||

| Age | r | 0.023 | −0.054 | 0.121 | −0.073 | 0.126 | −0.103 | −0.008 | 0.082 |

| p | 0.863 | 0.689 | 0.370 | 0.589 | 0.346 | 0.443 | 0.953 | 0.539 | |

| Gravidity | r | −0.287 | 0.188 | 0.121 | −0.126 | 0.011 | −0.255 | −0.026 | 0.087 |

| p | 0.028 | 0.154 | 0.366 | 0.344 | 0.936 | 0.051 | 0.845 | 0.514 | |

| Parity | r | −0.145 | 0.168 | 0.065 | −0.064 | 0.025 | −0.215 | 0.070 | 0.132 |

| p | 0.274 | 0.203 | 0.628 | 0.629 | 0.849 | 0.102 | 0.599 | 0.320 | |

| Gestational weeks at which fetal anomaly was detected | r | 0.074 | 0.017 | −0.263 | −0.001 | 0.120 | 0.051 | −0.003 | 0.067 |

| p | 0.578 | 0.896 | 0.046 | 0.993 | 0.365 | 0.701 | 0.984 | 0.616 | |

| Number of detected anomalies | r | 0.090 | 0.012 | 0.126 | −0.042 | 0.097 | 0.003 | 0.084 | 0.200 |

| p | 0.500 | 0.926 | 0.346 | 0.750 | 0.465 | 0.982 | 0.526 | 0.129 | |

| Model Characteristics | Value |

|---|---|

| Omnibus Test of Model Coefficients | χ² = 57.277, df = 5, p < 0.001 |

| −2 Log Likelihood | 150.582 |

| Cox and Snell R² | 0.306 |

| Nagelkerke R² | 0.417 |

| Hosmer–Lemeshow Test | χ² = 6.034, df = 8, p = 0.643 |

| Mean VIF | 1.075 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Can, S.T.; Yıldız, S.; Sağlam, C.; Golbasi, H.; Ekin, A. Evaluation of Spousal Support and Stress Coping Styles of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Fetal Anomaly. Medicina 2025, 61, 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050868

Can ST, Yıldız S, Sağlam C, Golbasi H, Ekin A. Evaluation of Spousal Support and Stress Coping Styles of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Fetal Anomaly. Medicina. 2025; 61(5):868. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050868

Chicago/Turabian StyleCan, Sevim Tuncer, Sevler Yıldız, Ceren Sağlam, Hakan Golbasi, and Atalay Ekin. 2025. "Evaluation of Spousal Support and Stress Coping Styles of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Fetal Anomaly" Medicina 61, no. 5: 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050868

APA StyleCan, S. T., Yıldız, S., Sağlam, C., Golbasi, H., & Ekin, A. (2025). Evaluation of Spousal Support and Stress Coping Styles of Pregnant Women Diagnosed with Fetal Anomaly. Medicina, 61(5), 868. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050868