Late-Onset Depression and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Temporal Relationships and Predictive Associations

Abstract

1. Introduction

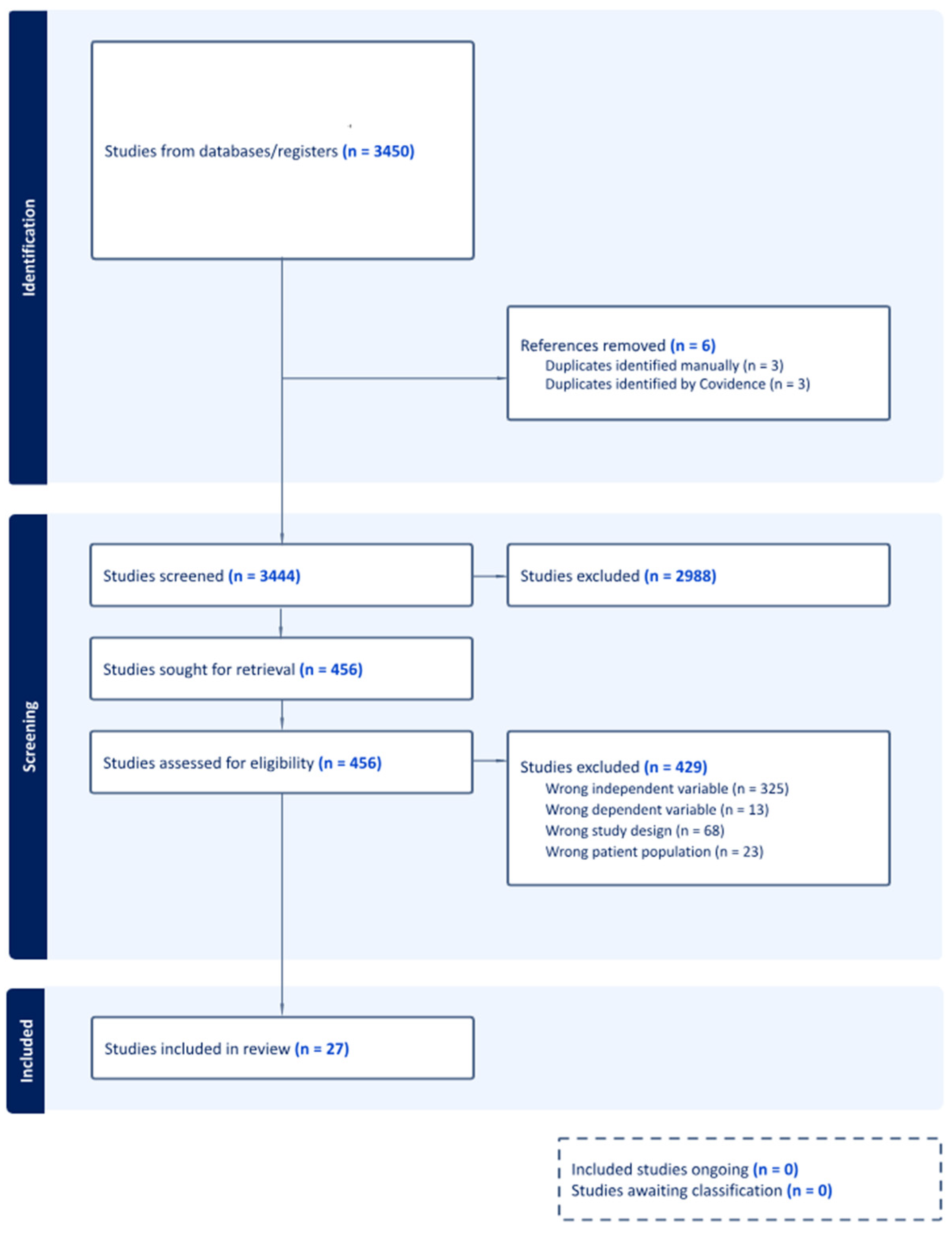

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Study Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Temporal Association and Dementia Risk Magnitude

3.2. Late-Onset Depression and Alzheimer’s Disease Risk

3.3. Age of Depression Onset and Dementia Risk or Prevalence

3.4. Medication Use and Dementia Risk in Patients with Late-Onset Depression

3.5. Sex and Dementia Risk in Late-Onset Depression

3.6. Age and Dementia Risk in LOD

3.7. Late-Onset Depression Severity and Dementia Risk

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LOD | Late-Onset Depression |

| EOD | Early-Onset Depression |

| HPA | Hypothalamic-Pituitary Axis |

| AD | Alzheimer’s Disease |

Appendix A

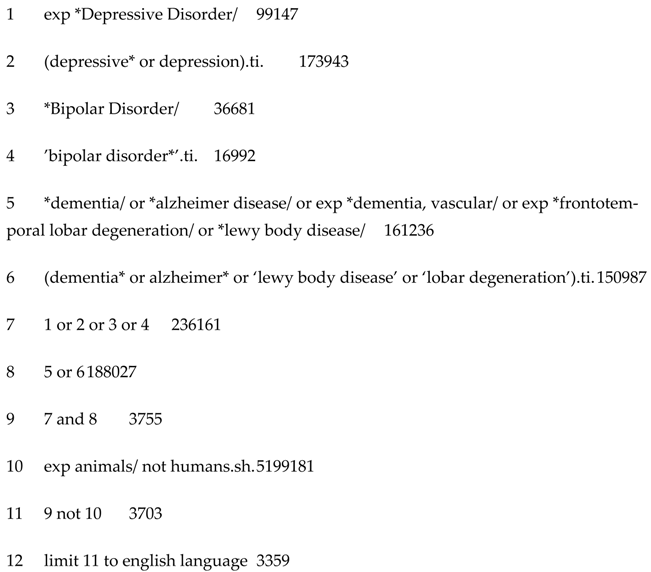

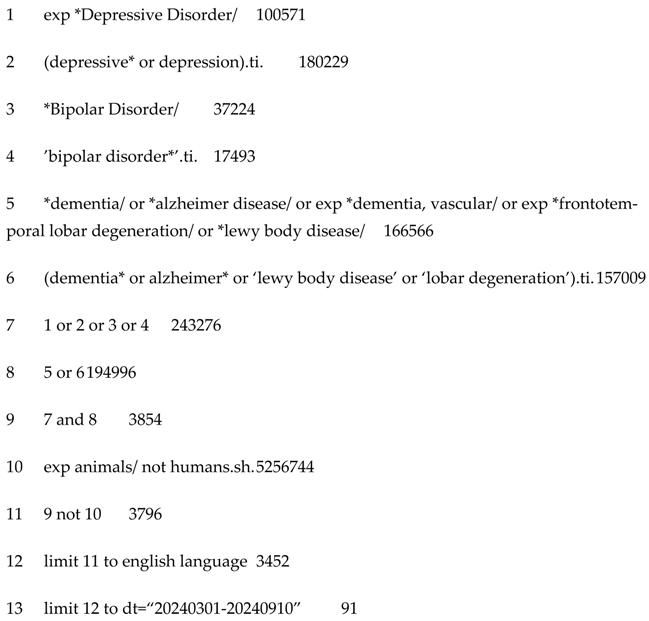

Search Strategy–Conducted in March 2024 and September 2024

- Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations <1 March 2024>

- Ovid MEDLINE(R) Epub Ahead of Print and In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily <9 September 2024>

Appendix B

| Study (Author and Year of Publication) | Country of Study | Study Type | Sample Size | Age of Onset for LOD | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elser et al., [25] | Denmark | Retrospective Cohort | Depression: 246, 499 Without Depression: 1,190,302 | ≥60 years | Compared to controls without depression, individuals with LOD within 1–10 years, 10–20 years and 20–39 years had higher risk of dementia

Compared to individuals with EOD (18–44 years) or middle-onset (45–59 years), patients with LOD had the highest dementia risks regardless of time elapsed between index date and depression diagnosis (1–10 years; >10–20 years; 20–30 years; 1–39 years). The hazard of dementia among those with LOD was low compared to those with early or middle-onset depression at 1–10 years, >10–20 years and 20–39 years since index date |

| Hickey et al., [35] | Denmark | Prospective Cohort | Total: 25,651 Depression: 8086 | ≥60 years | Compared to controls without depression, Danish nurses with LOD had a higher risk of dementia (HR: 5.85, CI: 5.17–6.64). This HR was higher than nurses with midlife only and recurrent (mid and late life depression) |

| Yang et al., [36] | Sweden | Cohort | Total: 41,727 | >65 years | LLD depression was associated with increased odds of developing all-cause dementia (OR: 2.16), AD (OR: 1.57) and VaD (OR: 3.11). All other depression onsets were similarly associated with dementia. |

| Lee et al., [14] | Hong Kong | Prospective Cohort | Total: 16,608 | ≥65 years | Compared to controls without depression, individuals with LOD had a non-significant but lower hazard of incident dementia (HR: 0.91, p = 0.69). Only those with persistent depression (adulthood and LOD) showed a slightly increased hazard of dementia (HR: 1.13, p = 0.001) |

| Yu et al., [44] | Republic of Korea | Retrospective Cohort | Depression: 1824 Without Depression: 374,852 | ≥65 years | Compared to controls without depression, depression onset ≤44 years was not significantly associated with an increased odds of dementia. Compared to controls without depression, depression onset at 45–64 years and ≥65 years depression was associated with a significantly higher risk of developing dementia (OR 2.72, p = 0.003; OR 2.05, p = 0.001). The highest dementia risk was among Individuals with LOD. |

| Heser et al., [26] | Germany | Prospective Cohort | Total: 97,110 | ≥65 years | Incident depression diagnosis at age 65 or older increased subsequent risk of dementia (IRR = 1.11, p < 0.01). When stratified according to age at diagnosis (65–74, 75–84, and 85+), the risk of dementia was highest for the 65–74 year old age group (IRR = 2, p < 0.01). In older adults, the risk of dementia was significantly higher among those with depression compared to non-depressed individuals. Ages 65–74: Depression was associated with a 3.84-fold increased dementia risk, though this difference was not significant after 9 quarters. Ages 75–84: Dementia risk was 2.3 times higher in depressed individuals, with no significant difference after 8 quarters. Ages 85 and above: Depression was linked to a 1.34-fold increased dementia risk, with no significant difference after 3 quarters. |

| Yang et al., [47] | Taiwan | Retrospective Cohort | Depression: 6028 Without Depression: 40,411 | ≥65 years | Aspirin use among patients with LOD was associated with a lower risk of dementia (HR =0.734, 95% CI 0.641–0.841, p < 0.001) |

| Holmquist et al., [27] | Sweden | Retrospective Cohort | Cohort 1: Cases and Controls–Total = 238,772 Cohort 2: Siblings–Total = 50,644 | ≥50 years | Matched cohort: Odds of dementia were highest within 6 months of a depression diagnosis (aOR 15.20, 95% CI 11.85–19.50; p < 0.001), which decreased over time but persisted over 20 years of follow-up (aOR 1.58, 95% CI 1.27–1.98; p < 0.001) Sibling cohort: Odds of dementia were highest within 6 months of a depression diagnosis (aOR 20.85, 95% CI 9.63–45.12; p < 0.001), which decreased over time but persisted over 20 years of follow-up (aOR 2.33, 95% CI 1.32–4.11; p < 0.001) |

| Singh-Manoux et al., [50] | England | Prospective Cohort | Total: 10,308 | Mean age: 70 years | LLD but not midlife (mean age 50 year) was associated with a higher risk of dementia |

| Yang et al., [48] | Taiwan | Retrospective Cohort | Total: 45,973 | ≥65 years | Among patients with LOD, compared to non-statin users, patients using statins had a lower risk of dementia (aHR = 0.674, 95% CI 0.547–0.832, p < 0.001). Among patients with LOD, patients taking a non-statin lipid lowering agent did not have a significant reduction in the hazards risk of dementia compared to those who did not use LLAs (HR 0.826, p = 0.117, 95% CI 0.65–1.049; HR 0.724, p = 0.349, 95% CI 0.369–1.422). |

| Kohler et al., [38] | The Netherlands | Retrospective Cohort | Total: 35,791 | ≥50 years | Unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratio showed that LOD was associated with a higher risk of dementia: (adjusted HR = 2.03, 95% CI = 1.56–2.64) compared to those without depression. |

| Tam and Lam, [39] | China | Case-Control | Depression: 81 Without Depression: 468 | ≥50 years | Compared to those without depression, LOD patients had an increased risk of progression to dementia at 2 years follow-up |

| Heser et al., [31] | Germany | Prospective Cohort | Total: 2663 | ≥60 years | LOD was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (HR: 1.39, CI: 0.83–2.34), AD (HR: 1.53, CI: 0.75–3.12) and dementia of other etiology (HR: 1.24, CI: 0.54–2.80), albeit all were non-significant VLOD at ≥65 years was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia (HR: 1.65, p < 0.10). When the age cut-offs for VLOD were altered to 70 or 75 years, the risk associations increased Adjusted Models: VLOD increased the risk for all-cause dementia (HR: 1.51, CI: 0.86–2.65), Alzheimer’s Disease (HR: 1.31, CI: 0.58–2.95), and dementia of other etiology (HR: 2.05, CI: 0.89–1.97) |

| Vilalta-Franch et al., [29] | Spain | Retrospective Cohort | Total: 451 | ≥65 years | Compared to those with EOD, a greater proportion of LOD patients developed dementia (χ² = 2.847; df = 1; p = 0.092). Compared to those with EOD, a greater proportion of LOD patients developed Alzheimer’s disease (χ² = 8.475; df = 2; p = 0.014). Compared to those with no depression, Late-Onset Minor Depression or Dysthymia and Late-Onset Major Depression were associated with a greater risk of dementia development, which was further increased if patients had DEDS.

|

| Olazaran et al., [28] | Spain | Retrospective Cohort | Never Depression: 1471 Past Depression: 85 Present Depression: 185 Present and Past Depression: 66 | Present Depression = Within the last 10 years | prD (Present depression) and prpD (present and past depression) was associated with an increased risk of all dementia (OR = 1.84 (95% CI: 1.01–3.35), p < 0.05; OR = 2.73 (95% CI: 1.08–6.87), p < 0.05.). Past depression did not have a statistically significant association. Dementia due to AD showed non-significant associations with past depression and present depression. However, past and present depression showed a statistically significant association with dementia due to AD. |

| Barnes et al., [32] | USA | Cohort | Total: 13535 | Defined late-life based on diagnoses between 1990–2000. Baseline age of participants was 40–55 years old in 1964–1973 | Hazard of dementia was significantly higher among those with depressive symptoms in midlife only (HR 1.19 [95% CI, 1.07–1.32]), late-life only (HR 1.72 [1.54–1.92]), and those with both (1.77 [1.52–2.06]). Individuals with LLD symptoms had an increased risk of AD (HR, 2.06 [95% CI, 1.67–2.55]), and Vascular Dementia (HR 1.47 [1.01–2.14]). Individuals with midlife and LLDsymptoms had an increased risk of AD (HR, 1.99 [95% CI, 1.47–2.69]) and VaD (3.51 [2.44–5.05]). |

| Li et al., [40] | USA | Prospective Cohort | Total = 3410 | ≥50 years | LLD was associated with increased risk of all-cause dementia (aHR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.16–1.84), but early life depression was not (aHR = 1.10, 95% CI 0.83–1.47) |

| Ohanna et al., [41] | Israel | Retrospective Case-Control | Without LOD: 51 LOD: 51 | ≥50 years | There was no significant association between LOD and dementia risk. However, a family history of dementia in patients with LOD (χ21 = 53, p = 0.022) and the duration of the first LOD episode (χ2101 = 1.8, p = 0.048) were associated with dementia development. |

| Brommelhoff et al., [24] | Sweden | Case-Control | Case Control: Controls = 12133; Cases = 547. Co-Twin Control = 146 Twin Pairs | Recent Onset: within 10 years of dementia onset Early onset: > 10 years prior to dementia onset | Case Control Analysis: Individuals with a recent onset of depression were 3.87 times more likely than those with no depression to have dementia (CI = 2.10, 7.14), and 2.62 times more likely to have AD (CI = 1.12, 6.17) Early onset of depression was not associated with an increased risk of dementia (OR = 0.90, CI = 0.44, 1.85) or AD (OR = 0.66, CI = 0.24, 1.81). |

| van Reekum et al., [43] | Canada | Cross-Sectional | N = 245; (N = 229 for admission MMSE N = 125 for discharge MMSE; N = 191 for admission MDRS) | ≥60 years | A significantly greater proportion of patients with LOD (47.5%) developed dementia compared to those with EOD (31.5%) (p = 0.025) |

| Buntinx et al., [42] | Netherlands | Retrospective Cohort | LOD = 489 Without LOD = 18614 | ≥50 years | Compared to those without LOD, patients with LOD had a higher odds (OR 2.38, 95% CI = 1.08–5.06) and hazard ratio (HR 2.55, 95% CI = 1.19–5.47; p = 0.03) of dementia |

| Speck et al., [30] | USA | Case-Control Study | Control: 300 Dementia: 294 | Depression < 10 years before dementia and ≥10 years | Depression occurring ≥ 10 years before dementia symptom onset increased risk of AD regardless of whether we looked at depression from any source (OR = 1.7, CI = 1.0–2.9) or restricted it to depression not related to loss/grief (OR = 2.4; CI = 1.2–4.5). However, depression occurring less than 10 years before dementia symptom onset did not increase risk of AD regardless of whether we looked at depression from any source (OR = 1.1, CI = 0.5–2.3) or restricted it to depression not related to loss/grief (OR = 1.0; CI = 0.3–2.8). |

| Geerlings et al., [33] | Netherlands | Population-based cohort study | Total = 486 | ≥60 years | Having a history of depression increased the risk of AD (HR 2.46; 95% CI 1.15 to 5.26). When history of depression was stratified by early and late onset, AD patients with EOD had increased risk of developing AD (HR 3.70; 95%CI 1.43 to 9.56) whereas this increased risk was less pronounced in subjects with a LOD (HR 1.71; 95% CI 0.62 to 4.74). When using all-cause dementia as the outcome, the results did not change. |

| Heun et al., [34] | Germany | Cross-Sectional | Total = 147 | Stratified onset from the time of dementia diagnosis: 46–50; 41–45, 36–40, 31–35, 26–30, 21–25, 16–20, 11–15, 6–10, 0–5 years | There was a correlation between the age at onset of the depressive disorder and the age at onset of dementia (Pearson’s coefficient R = 0.447, p = 0.001) |

| Pálsson et al., [45] | Sweden | Retrospective Cohort | Controls = 227 Depression = 62 | ≥65 years | The incidence of dementia between the ages of 85 and 88 in mentally healthy individuals and in depressed individuals did not differ significantly. Early-onset depression, particularly early-onset MDD, is associated with a higher risk of dementia compared to mentally healthy individuals, with statistically significant findings for early-onset MDD. LOD and dysthymia do not show statistically significant associations with dementia incidence. |

| Su et al., [49] | Taiwan | Retrospective Cohort | Total: 56,154 | 60–80 years and > 80 years | Comparing antidepressant user (both high and low) to non-user -No difference in risk of dementia With high antidepressant use, dementia more likely in: male patients (HR: 1.23, 95% CI: 1.01–1.50), those older than 80 years (HR: 1.44, 95% CI: 1.02–2.04), and those with major depression (HR: 1.56, 95% CI: 1.11–2.20) |

| Zalsman et al., [46] | Israel | Cohort | Total: 502 | ≥50 years | OR for dementia in patients with LOD (vs. those without)–1.94 (95% CI 0.98 to 3.84, p = 0.06) |

Appendix C

Quality Assessment Tables

| Cohort Studies | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

| Barnes et al., [32] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| Heser et al., [31] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Kohler et al., [38] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Vilalta-Franch et al., [29] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Olazaran et al., [28] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Li et al., [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Buntinx et al., [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| Elser et al., [25] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Heser et al., [26] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Hickey et al., [35] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Holmquist et al., [27] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lee et al., [37] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Singh-Manoux et al., [50] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Yang et al., [48] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Yang et al., [47] | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Yang et al., [36] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Yu et al., [44] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| Geerlings et al., [33] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Su et al., [49] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| Pálsson et al., [45] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Zalsman et al., [46] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 |

| van Reekum et al., [43] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Heun et al., [34] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Case-Control Studies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

| Tam and Lam, [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ohanna et al., [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Brommelhoff et al., [24] | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Speck et al., [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

References

- Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dementia numbers in Canada | Alzheimer Society of Canada. (n.d.). Available online: https://alzheimer.ca/en/about-dementia/what-dementia/dementia-numbers-canada (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. A Dementia Strategy for Canada: Together We Aspire. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/dementia-strategy.html (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Nordestgaard, L.T.; Christoffersen, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Shared Risk Factors between Dementia and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Flier, W.M. Epidemiology and risk factors of dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76 (Suppl. S5), v2–v7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, R.J.; Aisen, P.S.; De Strooper, B.; Fox, N.C.; Lemere, C.A.; Ringman, J.M.; Salloway, S.; Sperling, R.A.; Windisch, M.; Xiong, C. Autosomal-dominant Alzheimer’s disease: A review and proposal for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2011, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Sommerlad, A.; Ames, D.; Ballard, C.; Banerjee, S.; Brayne, C.; Burns, A.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Cooper, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet 2020, 396, 413–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranson, J.M.; Rittman, T.; Hayat, S.; Brayne, C.; Jessen, F.; Blennow, K.; van Duijn, C.; Barkhof, F.; Tang, E.; Mummery, C.J.; et al. Modifiable risk factors for dementia and dementia risk profiling. A user manual for Brain Health Services—Part 2 of 6. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2021, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wragg, R.E.; Jeste, D.V. Overview of depression and psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Psychiatry 1989, 146, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.K.Y.; Chan, W.C.; Spector, A.; Wong, G.H.Y. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and apathy symptoms across dementia stages: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2021, 36, 1330–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Thomas, A.J. Depression and dementia: Cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas 2014, 79, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butters, M.A.; Young, J.B.; Lopez, O.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Mulsant, B.H.; Reynolds III, C.F.; DeKosky, S.T.; Becker, J.T. Pathways linking late-life depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 10, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.T.C.; Fung, A.W.T.; Richards, M.; Chan, W.C.; Chiu, H.F.K.; Lee, R.S.Y.; Lam, L.C.W. Risk of incident dementia varies with different onset and courses of depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, L.L.; Goodwin, G.M.; Ebmeier, K.P. The cognitive neuropsychology of depression in the elderly. Psychol. Med. 2007, 37, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, L.L.; Le Masurier, M.; Ebmeier, K.P. White matter hyperintensities in late life depression: A systematic review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 79, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belvederi Murri, M.; Pariante, C.; Mondelli, V.; Masotti, M.; Atti, A.R.; Mellacqua, Z.; Antonioli, M.; Ghio, L.; Menchetti, M.; Zanetidou, S.; et al. HPA axis and aging in depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 41, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerritsen, L.; Twait, E.L.; Jonsson, P.V.; Gudnason, V.; Launer, L.J.; Geerlings, M.I. Depression and Dementia: The Role of Cortisol and Vascular Brain Lesions. AGES-Reykjavik Study. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2022, 85, 1677–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linnemann, C.; Lang, U.E. Pathways Connecting Late-Life Depression and Dementia. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera-González, M.D.P.; Cantón-Habas, V.; Rich-Ruiz, M. Aging, depression and dementia: The inflammatory process. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. Off. Organ Wroc. Med. Univ. 2022, 31, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, M.; Karim, H.T.; Becker, J.T.; Lopez, O.L.; Anderson, S.J.; Aizenstein, H.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Zmuda, M.D.; Butters, M.A. Late-life depression and increased risk of dementia: A longitudinal cohort study. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLOS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brommelhoff, J.A.; Gatz, M.; Johansson, B.; McArdle, J.J.; Fratiglioni, L.; Pedersen, N.L. Depression as a risk factor or prodromal feature for dementia? Findings in a population-based sample of Swedish twins. Psychol. Aging 2009, 24, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elser, H.; Horvath-Puho, E.; Gradus, J.L.; Smith, M.L.; Lash, T.L.; Glymour, M.M.; Sorensen, H.T.; Henderson, V.W. Association of Early-, Middle-, and Late-Life Depression with Incident Dementia in a Danish Cohort. JAMA Neurol. 2023, 80, 949–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heser, K.; Fink, A.; Reinke, C.; Wagner, M.; Doblhammer, G. The temporal association between incident late-life depression and incident dementia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmquist, S.; Nordstrom, A.; Nordstrom, P. The association of depression with subsequent dementia diagnosis: A Swedish nationwide cohort study from 1964 to 2016. PLoS Med. 2020, 17, e1003016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazaran, J.; Trincado, R.; Bermejo-Pareja, F. Cumulative effect of depression on dementia risk. Int. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 2013, 457175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Vilalta-Franch, J.; Lopez-Pousa, S.; Llinas-Regla, J.; Calvo-Perxas, L.; Merino-Aguado, J.; Garre-Olmo, J. Depression subtypes and 5-year risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease in patients aged 70 years. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 28, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speck, C.E.; Kukull, W.A.; Brenner, D.E.; Bowen, J.D.; McCormick, W.C.; Teri, L.; Pfanschmidt, M.L.; Thompson, J.D.; Larson, E.B. History of depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Epidemiology 1995, 6, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heser, K.; Tebarth, F.; Wiese, B.; Eisele, M.; Bickel, H.; Kohler, M.; Mosch, E.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Konig, H.-H.; et al. Age of major depression onset, depressive symptoms, and risk for subsequent dementia: Results of the German study on Ageing, Cognition, and Dementia in Primary Care Patients (AgeCoDe). Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 1597–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K.; Byers, A.L.; McCormick, M.; Schaefer, C.; Whitmer, R.A. Midlife vs late-life depressive symptoms and risk of dementia: Differential effects for Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2012, 69, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerlings, M.I.; den Heijer, T.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. History of depression, depressive symptoms, and medial temporal lobe atrophy and the risk of Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2008, 70, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heun, R.; Kockler, M.; Ptok, U. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease: Is there a temporal relationship between the onset of depression and the onset of dementia? Eur. Psychiatry J. Assoc. Eur. Psychiatr. 2002, 17, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, M.; Hueg, T.K.; Priskorn, L.; Uldbjerg, C.S.; Beck, A.L.; Anstey, K.J.; Lim, Y.-H.; Brauner, E.V. Depression in Mid- and Later-Life and Risk of Dementia in Women: A Prospective Study within the Danish Nurses Cohort. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. JAD 2023, 93, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Li, X.; Pan, K.-Y.; Yang, R.; Song, R.; Qi, X.; Pedersen, N.L.; Xu, W. Association of life-course depression with the risk of dementia in late life: A nationwide twin study. Alzheimer’s Dementia J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2021, 17, 1383–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohler, S.; Buntinx, F.; Palmer, K.; van den Akker, M. Depression, vascular factors, and risk of dementia in primary care: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2015, 63, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, C.W.C.; Lam, L.C.W. Association between late-onset depression and incident dementia in Chinese older persons. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 23, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Wang, L.Y.; Shofer, J.B.; Thompson, M.L.; Peskind, E.R.; McCormick, W.; Bowen, J.D.; Crane, P.K.; Larson, E.B. Temporal relationship between depression and dementia: Findings from a large community-based 15-year follow-up study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohanna, I.; Golander, H.; Barak, Y. Does late onset depression predispose to dementia? A retrospective, case-controlled study. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntinx, F.; Kester, A.; Bergers, J.; Knottnerus, J.A. Is depression in elderly people followed by dementia? A retrospective cohort study based in general practice. Age Ageing 1996, 25, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reekum, R.; Simard, M.; Clarke, D.; Binns, M.A.; Conn, D. Late-life depression as a possible predictor of dementia: Cross-sectional and short-term follow-up results. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 7, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, O.-C.; Jung, B.; Go, H.; Park, M.; Ha, I.-H. Association between dementia and depression: A retrospective study using the Korean National Health Insurance Service-National Sample Cohort database. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pálsson, S.; Aevarsson, O.; Skoog, I. Depression, cerebral atrophy, cognitive performance and incidence of dementia. Population study of 85-year-olds. Br. J. Psychiatry 1999, 174, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalsman, G.; Aizenberg, D.; Sigler, M.; Nahshony, E.; Karp, L.; Weizman, A. Increased risk for dementia in elderly psychiatric inpatients with late-onset major depression. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2000, 188, 242–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Chiu, C.-C.; Teng, H.-W.; Huang, C.-T.; Liu, C.-Y.; Huang, L.-J. Aspirin and Risk of Dementia in Patients with Late-Onset Depression: A Population-Based Cohort Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1704879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Teng, H.-W.; Lai, Y.-T.; Li, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-C.; Yang, A.C.; Chan, H.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-H.; Lin, C.-F.; Hsu, F.-Y.; et al. Statins Reduces the Risk of Dementia in Patients with Late-Onset Depression: A Retrospective Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-A.; Chang, C.-C.; Yang, Y.-H.; Chen, K.-J.; Li, Y.-P.; Lin, C.-Y. Risk of incident dementia in late-life depression treated with antidepressants: A nationwide population cohort study. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh-Manoux, A.; Dugravot, A.; Fournier, A.; Abell, J.; Ebmeier, K.; Kivimaki, M.; Sabia, S. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Before Diagnosis of Dementia: A 28-Year Follow-up Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korczyn, A.D.; Halperin, I. Depression and dementia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 283, 139–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, A.L.; Covinsky, K.E.; Barnes, D.E.; Yaffe, K. Dysthymia and Depression Increase Risk of Dementia and Mortality Among Older Veterans. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2012, 20, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Hu, Z.; Wei, L.; Qin, X.; McCracken, C.; Copeland, J.R. Severity of depression and risk for subsequent dementia: Cohort studies in China and the UK. Br. J. Psychiatry 2008, 193, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Barnes, L.L.; Mendes de Leon, C.F.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Schneider, J.S.; Bach, J.; Pilat, J.; Beckett, L.A.; Arnold, S.E.; Evans, D.A.; et al. Depressive symptoms, cognitive decline, and risk of AD in older persons. Neurology 2002, 59, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birks, J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006, 2006, CD005593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Middelaar, T.; van Vught, L.A.; Moll van Charante, E.P.; Eurelings, L.S.M.; Ligthart, S.A.; van Dalen, J.W.; van den Born, B.J.H.; Richard, E.; van Gool, W.A. Lower dementia risk with different classes of antihypertensive medication in older patients. J. Hypertens. 2017, 35, 2095–2101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, A.; Garriga, C.; Arden, N.K.; Lovestone, S.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Cooper, C.; Edwards, C.J. Protective effect of antirheumatic drugs on dementia in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2017, 3, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kern, D.M.; Cepeda, M.S.; Lovestone, S.; Seabrook, G.R. Aiding the discovery of new treatments for dementia by uncovering unknown benefits of existing medications. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2019, 5, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, P.; Boccardi, V. The impact of aging in dementia: It is time to refocus attention on the main risk factor of dementia. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 65, 101210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study | Timing of Depression Onset Relative to Dementia | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Heser et al., [26] | Within 3 months | Strongest association; no significant risk after ~3 years |

| Holmquist et al., [27] | Within 6 months; up to 20 years | Strongest early risk; significant risk persisted up to 20 years |

| Olazaran et al., [28] | Within 10 years; recent and past episodes | Strong association; recent + past depression → highest odds (OR = 2.73, CI 1.08–6.87) |

| Brommelhoff et al., [24] | Within 10 years | Strong association within 10 years |

| Elser et al., [25] | Within 10 years; up to 20 years | Persistent significant risk even after 20 years |

| Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Vilalta-Franch et al., [29] | LOD significantly increased AD risk |

| Barnes et al., [32] | LOD significantly increased AD risk |

| Heser et al., [31] | LOD significantly increased AD risk |

| Geerlings et al., [33] | LOD increased AD risk (HR = 1.71, CI 0.62–4.74), but less than EOD (HR = 3.70, CI 1.43–9.56) |

| Brommelhoff et al., [24] | Depression within 10 years of AD diagnosis increased risk |

| Speck et al., [30] | Higher AD risk with depression episodes >10 years prior |

| Olazaran et al., [28] | Past + present depression associated with AD; individually, not significant |

| Heun et al., [34] | No significant association between timing of depression and AD onset; depression ↑ within 5 years of AD onset |

| Study | Comparison/Focus | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Hickey et al., [35] | LOD vs. midlife/recurrent depression | LOD associated with much higher dementia risk |

| Barnes et al., [32] | LOD vs. midlife depression | LOD significantly increased dementia risk |

| Elser et al., [25] | Early/mid/late depression vs. controls | All increased dementia risk; LOD had lowest hazard (HR = 2.31) |

| Li et al., [39] | LOD vs. early depression | LOD (HR = 1.46); EOD not significant (HR = 1.10) |

| Geerlings et al., [33] | Early vs. late depression | EOD HR = 3.37; LOD HR = 2.51 |

| Pálsson et al., [44] | Early vs. LOD vs. controls | EOD → higher dementia risk; no significant LOD risk |

| Zalsman et al., [45] | LOD vs. non-depressed | Non-significant but increased odds with LOD |

| Yu et al., [43] | Midlife vs. LOD | Similar odds: midlife OR = 2.72; LOD OR = 2.05 |

| Kohler et al., [37] | LOD vs. controls | LOD HR > 2 |

| Buntinx et al, [41] | LOD vs. no LOD | LOD associated with increased dementia risk |

| Yang et al., [36] | LOD, all-cause, Alzheimer’s dementia | LOD → OR = 2.16 (all-cause), OR = 1.57 (Alzheimer’s); all depression ↑ risk |

| Heser et al., [26] | Incident depression at 65+ | IRR = 1.58; adjusted IRR = 1.11 (less after accounting for comorbidities) |

| Lee et al., [14] | LOD (65+) | Unadjusted HR = 1.97; not significant after adjusting for depression severity |

| Ohanna et al., [40] | Risk factors in LOD | Family history and duration of first depressive episode ↑ dementia risk |

| Heser et al., [31] | Age cutoff for LOD | Onset ≥70 independently predicted dementia |

| Tam et al., [38] | Conversion in elderly depressed (50+) | 19% converted to dementia in 2 yrs; OR = 3.44 vs. controls |

| Vilalta-Franch et al., [29] | LOD vs. early vs. control | Dementia in 5 yrs: LOD (24.7%), EOD (10%), control (5.6%) |

| van Reekum et al., [42] | Dementia prevalence in LOD vs. EOD | LOD = 47.5%; early = 31.5% (p = 0.025) |

| Study | Medication Examined | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Yang et al., [46] | Aspirin | Reduced dementia risk (aHR = 0.833; 95% CI 0.708–0.981; p = 0.029) |

| Yang et al., [47] | Lipid-lowering agents (e.g., statins) | Statins significantly associated with lower dementia risk |

| Su et al., [48] | Antidepressants | No significant effect on dementia risk in individuals with LOD |

| Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Heser et al., [26] | Stronger LOD–dementia association observed in males |

| Yang et al., [46] | Female sex identified as a significant dementia risk factor in LOD |

| Singh-Manoux et al., [49] | Females with LOD had higher dementia risk |

| Yu et al., [43] | Females with LOD exhibited elevated dementia risk compared to males |

| Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Heser et al., [26] | Strongest LOD–dementia association in ages 65–74, followed by 75–84, then 85+ |

| Yang et al., [46] | Increasing age identified as a significant dementia risk factor in LOD |

| Singh-Manoux et al., [49] | Each additional year of age increased dementia risk by 21% (HR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.19–1.24) |

| Study | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Hickey et al., [35] | Mild LOD (no hospitalization) had higher dementia risk (HR = 5.23) than severe LOD (HR = 3.14) |

| Holmquist et al., [27] | Severe LOD linked to greater dementia risk, especially for vascular dementia |

| Vilalta-Franch et al., [29] | Depression severity (minor vs. major) did not significantly impact dementia risk |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Boparai, J.K.; Clemens, M.; Jat, K. Late-Onset Depression and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Temporal Relationships and Predictive Associations. Medicina 2025, 61, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050839

Boparai JK, Clemens M, Jat K. Late-Onset Depression and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Temporal Relationships and Predictive Associations. Medicina. 2025; 61(5):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050839

Chicago/Turabian StyleBoparai, Josheil Kaur, Megan Clemens, and Khalid Jat. 2025. "Late-Onset Depression and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Temporal Relationships and Predictive Associations" Medicina 61, no. 5: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050839

APA StyleBoparai, J. K., Clemens, M., & Jat, K. (2025). Late-Onset Depression and Dementia: A Systematic Review of the Temporal Relationships and Predictive Associations. Medicina, 61(5), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61050839