Neovaginal Perforation in Sigmoid Vaginoplasty: An Underrecognized Complication—A Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

3. Result

3.1. Etiology and Pathophysiology

3.2. Clinical Presentation and Case Reports

3.3. Reported Cases

- Liguori et al. (2001) documented a case of acute peritonitis secondary to introital stenosis, leading to perforation of a neovagina constructed from a bowel segment [19].

- Amirian et al. (2011) reported a patient who presented with lower abdominal pain and fever [21]. CT imaging revealed free air in the retroperitoneum, and a leak through the vaginal apex was confirmed via vaginal contrast examination. This patient was successfully managed with conservative antibiotic therapy.

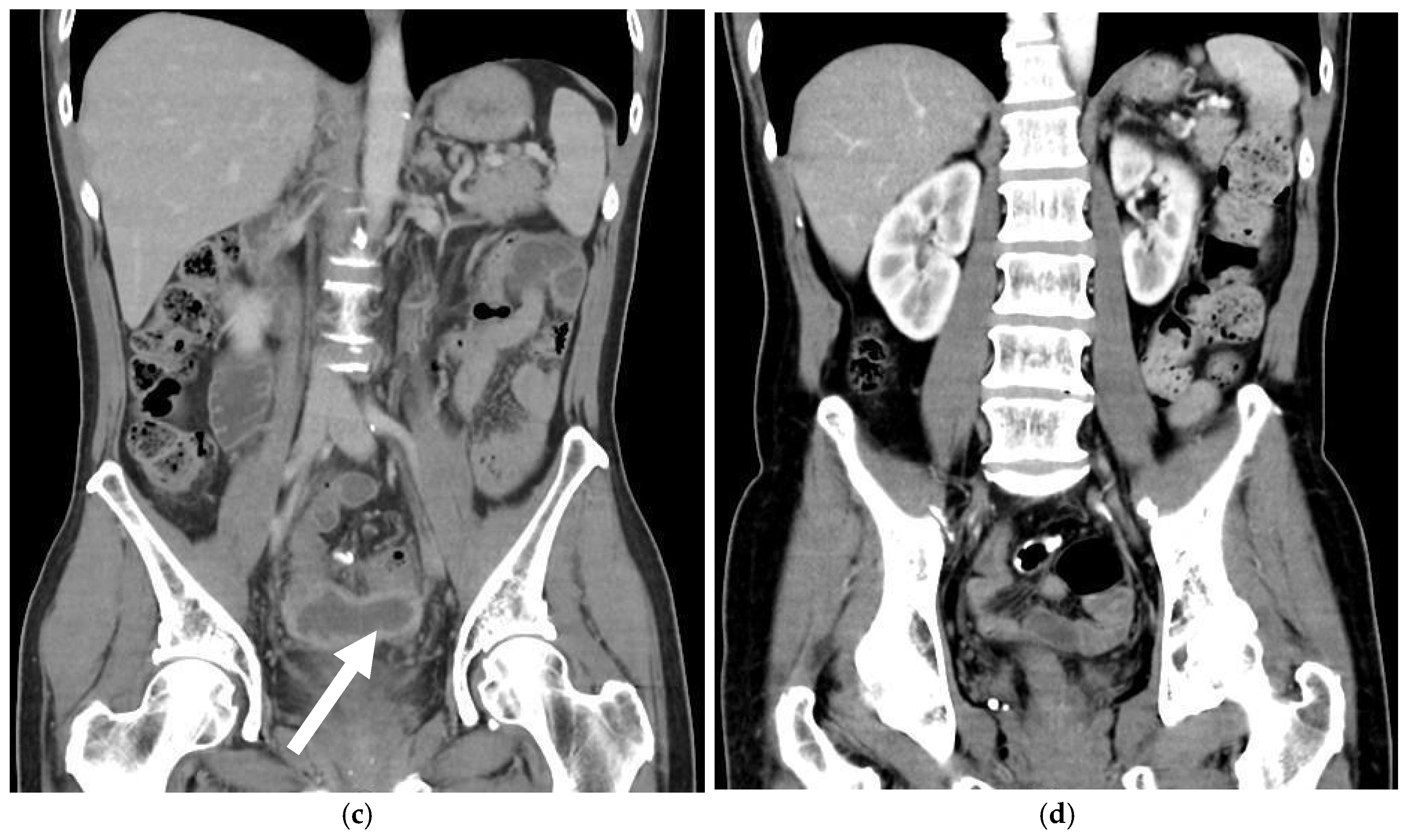

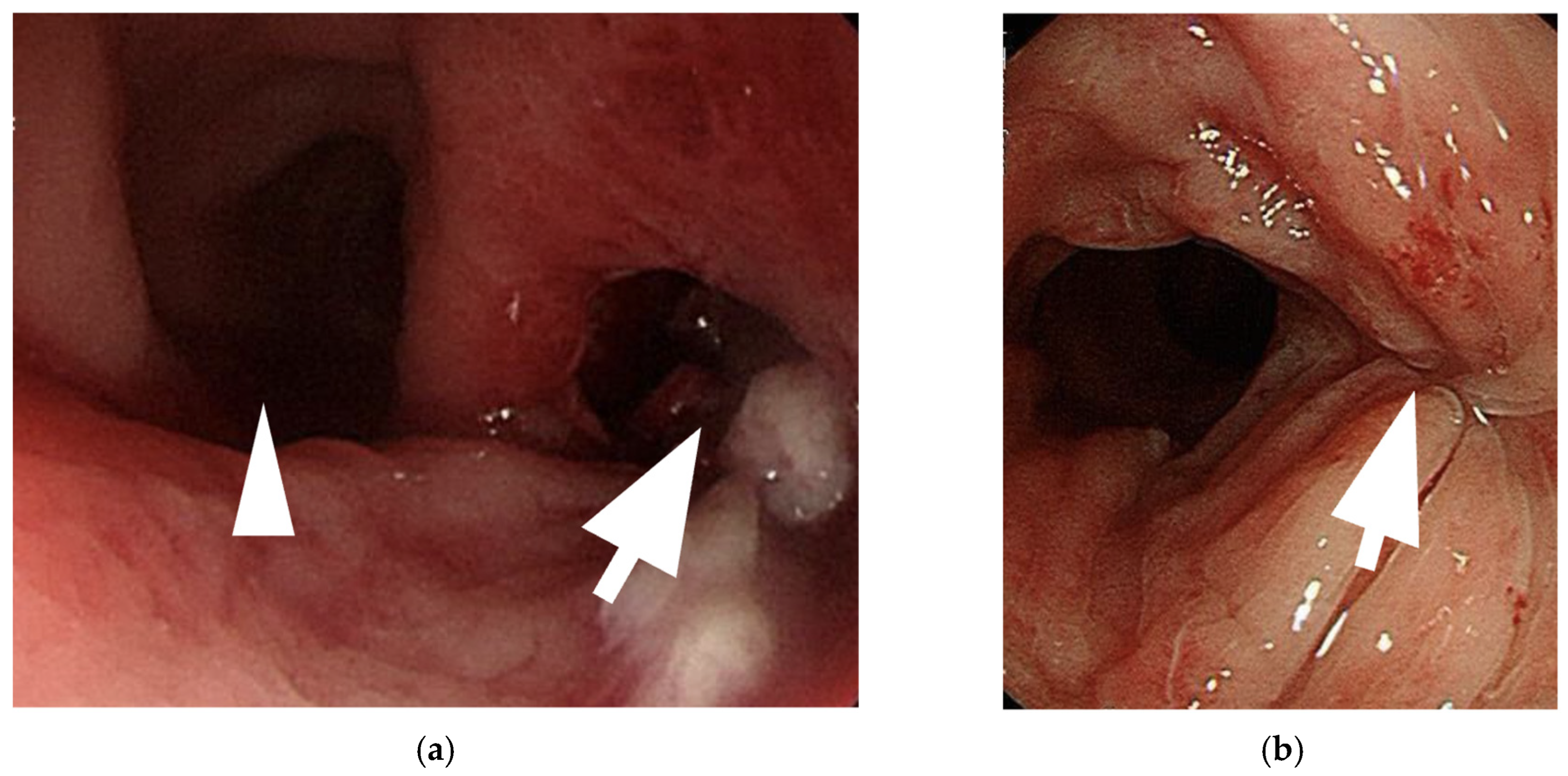

- Shimamura et al. (2015) described a case of neovaginal perforation complicated by an intra-abdominal abscess, where the clinical symptoms and radiologic findings were incongruent [18]. Surgical intraperitoneal drainage was performed due to concerns that the abscess might not resolve with antibiotics alone.

- Meece et al. reported two cases involving diffuse stenosis of unknown etiology, leading to ischemia and subsequent perforation of the sigmoid conduit [1]. One patient underwent midline laparotomy and was found to have multiple interloop abscesses, requiring prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy. The second patient, who developed vaginal stenosis secondary to a high-riding perineum, required laparoscopic sigmoid conduit resection, followed by a midline incision and internal suturing of the colon flap one month postoperatively.

3.4. Diagnosis

3.5. Management Strategies

4. Discussion

5. Future Directions

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meece, M.S.; Weber, L.E.; Hernandez, A.E.; Danker, S.J.; Paluvoi, N.V. Major complications of sigmoid vaginoplasty: A case series. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2023, 2023, rjad333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, J.F.X.I.V. The Formation of an Artificial Vagina by Intestinal Trransplantation. Ann. Surg. 1904, 40, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salgado, C.J.; Nugent, A.; Kuhn, J.; Janette, M.; Bahna, H. Primary Sigmoid Vaginoplasty in Transwomen: Technique and Outcomes. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4907208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendren, W.H.; Atala, A. Use of bowel for vaginal reconstruction. J. Urol. 1994, 152, 752–755; discussion 756–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, C.; Hastings, D. Vaginal reconstruction using cecal and sigmoid bowel segments in transsexual patients. J. Urol. 1974, 111, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedler, V.; Meuli-Simmen, C.; Guggenheim, M.; Schneller-Gustafsson, M.; Künzi, W. Laparoscopic technique for secondary vaginoplasty in male to female transsexuals using a modified vascularized pedicled sigmoid. Gynecol. Obstet. Investig. 2004, 57, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Campbell, B.; Ferrer, F. Robotic sigmoid vaginoplasty: A novel technique. Urology 2008, 72, 847–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, N.; Jindal, O.; Bhardwaj, D.K. Sigma-lead male-to-female gender affirmation surgery: Blending cosmesis with functionality. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2019, 7, e2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowier, A.; Esmat, M.; Hamza, R.T. Surgical and functional outcomes of sigmoid vaginoplasty among patients with variants of disorders of sex development. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2012, 38, 380–386; discussion 387–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, J.H.; Lee, K.C.; Park, J.M.; Kim, J.T.; Kim, M.C. Long-term results in patients after rectosigmoid vaginoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003, 112, 143–151. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, J.K.; Gearhart, S.L.; Gearhart, J.P. Vaginal reconstruction utilizing sigmoid colon: Complications and long-term results. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002, 37, 629–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, S.; Guillot-Tantay, C.; Sabbagh, P.; Vidart, A.; Bosset, P.-O.; Lebret, T.; Biardeau, X.; Schirmann, A.; Madec, F.-X. Systematic review of neovaginal prolapse after vaginoplasty in trans women. Eur. Urol. Open Sci. 2024, 66, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouman, M.-B.; van Zeijl, M.C.T.; Buncamper, M.E.; Meijerink, W.J.H.J.; van Bodegraven, A.A.; Mullender, M.G. Intestinal vaginoplasty revisited: A review of surgical techniques, complications, and sexual function. J. Sex. Med. 2014, 11, 1835–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manrique, O.J.; Adabi, K.; Martinez-Jorge, J.; Ciudad, P.; Nicoli, F.; Kiranantawat, K. Complications and patient-reported outcomes in male-to-female vaginoplasty-where we are today: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 80, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deliktas, H.; Ozcan, O.; Cullu, N.; Erdogan, O. Neovaginal perforation following sexual intercourse in a transsexual patient. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoder, W.Y.; Stief, C.G.; Burgmann, M.; Burges, A. Laparoscopic reconstruction of an iatrogenic perforation of the neovagina and urinary bladder by a neovaginal dilator in a patient with Mayer–Rokitansky–Küster–Hauser syndrome. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2015, 26, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, A.; Butt, S. Perforation of sigmoid neovagina in a patient with Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser syndrome. IDCases 2021, 24, e01110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimamura, Y.; Fujikawa, A.; Kubota, K.; Ishii, N.; Fujita, Y.; Ohta, K. Perforation of the neovagina in a male-to-female transsexual: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2015, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, G.; Trombetta, C.; Buttazzi, L.; Belgrano, E. Acute peritonitis due to introital stenosis and perforation of a bowel neovagina in a transsexual. Obstet. Gynecol. 2001, 97, 828–829. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, S.D.; Satterwhite, T.; Grant, D.W.; Kirby, J.; Laub, D.R.; VanMaasdam, J. Long-Term Outcomes of Rectosigmoid Neocolporrhaphy in Male-to-Female Gender Reassignment Surgery. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2015, 136, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, I.; Gögenur, I.; Rosenberg, J. Conservatively treated perforation of the neovagina in a male to female transsexual patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2011, 2011, bcr0820103241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvaggi, G.; Ceulemans, P.; De Cuypere, G.; VanLanduyt, K.; Blondeel, P.; Hamdi, M.; Bowman, C.; Monstrey, S. Gender identity disorder: General overview and surgical treatment for vaginoplasty in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005, 116, 135e–145e. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dy, G.W.; Jun, M.S.; Blasdel, G.; Bluebond-Langner, R.; Zhao, L.C. Outcomes of Gender Affirming Peritoneal Flap Vaginoplasty Using the Da Vinci Single Port Versus Xi Robotic Systems. Eur. Urol. 2021, 79, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buncamper, M.E.; van der Sluis, W.B. Surgical outcome after penile inversion vaginoplasty: A retrospective study of 475 transgender women. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2016, 138, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclère, F.M.; Casoli, V.; Weigert, R. Outcome of Vaginoplasty in Male-to-Female Transgenders: A Systematic Review of Surgical Techniques. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 1655–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lava, C.X.; Huffman, S.S.; Berger, L.E.; Marable, J.K.; Spoer, D.L.; Fan, K.L.; Lisle, D.M.; Del Corral, G.A. Rectovaginal fistula repair following vaginoplasty in transgender females: A systematic review of surgical techniques. Plast. Surg. 2025, 33, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Risk Factor | Potential Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Related Factors | MRKH syndrome or prior pelvic anomalies | Anatomical challenges and altered tissue planes may increase susceptibility |

| Poor compliance with dilation protocols | Improper dilation may lead to stenosis or pressure-related trauma | |

| Comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, smoking) | Impaired healing and tissue fragility | |

| Surgical Factors | Excessive graft length or tension | Increased mechanical stress and risk of ischemia |

| Inadequate neovaginal fixation | Higher risk of graft movement or instability | |

| Ischemia or poor vascular supply | Tissue necrosis or perforation risk | |

| Postoperative Factors | Introital stenosis | Distal obstruction and pressure buildup |

| Traumatic intercourse or instrumentation | Direct mechanical trauma to the neovaginal wall | |

| Inadequate postoperative follow-up | Delayed detection of complications |

| 2001 Liguori et al. [19] | 2011 Amirian et al. [21] | 2015 Shimamura et al. [18] | 2023 Meece et al. [1] | 2023 Meece et al. [1] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early complication after surgery | Total introital stenosis of the neovagina | no | Mild stenosis of the neovagina | Cellulitis and prolonged urinary retention on postoperative days 19 and 20 | Vaginal stenosis secondary to a high riding perineum |

| Symptom | Colicky abdominal pain, abdominal distension, and vomiting | Lower abdominal pain and fever | Persistent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting | Abdominal pain, vomiting, fever, large volume of mucinous discharge, and an inability to dilate | Abdominal pain, fever, nausea, vomiting |

| Onset | 1 year postoperatively | Unknown | Unknown | 1 year postoperatively | 3 years postoperatively |

| Image findings | A large amount of fetid mucus in the abdominal cavity via laparoscopy |

| CT: a massive abscess occupying a significant portion of the intra-abdominal cavity |

|

|

| Management | Exploratory laparotomy with primary repair | Intravenous antibiotics only | Exploratory laparotomy with primary repair | Midline laparotomy and resection of the necrotic sigmoid conduit | Laparoscopic resection of the sigmoid conduit |

| Prognosis | Recurrent total stenosis of the neovaginal introitus | Fair and no complications noted | No complications related to the surgery | Without further complication | Without further complication |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Y.-N.; You, J.-F.; Hu, C.-H. Neovaginal Perforation in Sigmoid Vaginoplasty: An Underrecognized Complication—A Literature Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040691

Huang Y-N, You J-F, Hu C-H. Neovaginal Perforation in Sigmoid Vaginoplasty: An Underrecognized Complication—A Literature Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(4):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040691

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Yen-Ning, Jeng-Fu You, and Ching-Hsuan Hu. 2025. "Neovaginal Perforation in Sigmoid Vaginoplasty: An Underrecognized Complication—A Literature Review" Medicina 61, no. 4: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040691

APA StyleHuang, Y.-N., You, J.-F., & Hu, C.-H. (2025). Neovaginal Perforation in Sigmoid Vaginoplasty: An Underrecognized Complication—A Literature Review. Medicina, 61(4), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040691