Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Risk Factors of CRD in Saudi Arabia

3. Burden of Chronic Respiratory Disease in Saudi Arabia

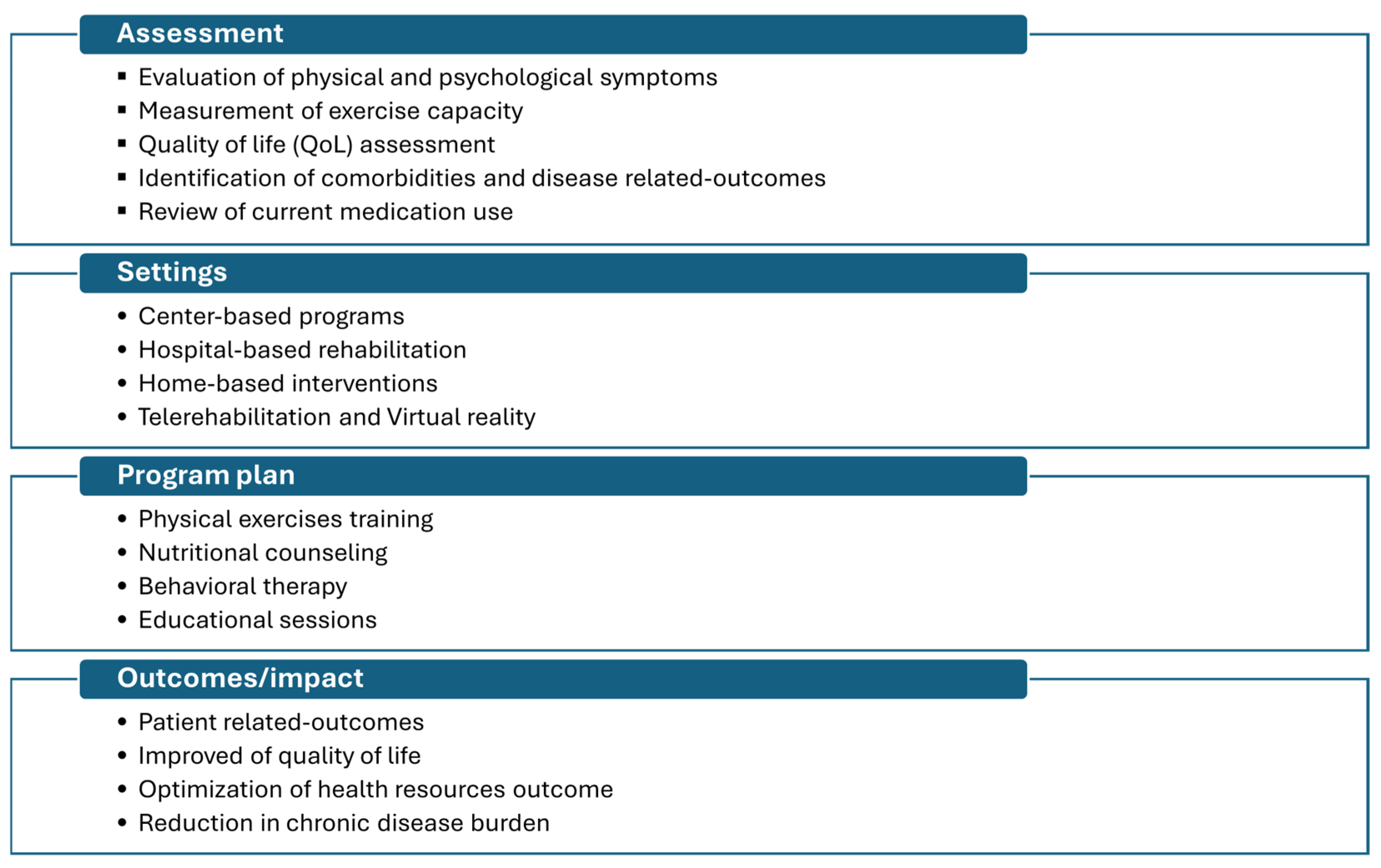

4. Management of CRD

5. Pulmonary Rehabilitation and Telerehabilitation: An Overview

6. Pulmonary Rehabilitation’s Current Status and Utilization in Saudi Arabia

7. Availability and Utilization of PR Services in Saudi Arabia

8. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Outcomes in Saudi Arabia

9. Stakeholder Perspectives on Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia

10. Future Directions and Forward Planning

11. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Momtazmanesh, S.; Moghaddam, S.S.; Ghamari, S.H.; Rad, E.M.; Rezaei, N.; Shobeiri, P.; Aali, A.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, Z.; Abdelmasseh, M.; et al. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990–2019: An update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 59, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.D.; Lavelle, M.; Boursiquot, B.C.; Wan, E.Y. Long-term complications of COVID-19. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2022, 322, C1–C11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.S. Prevalence, incidence, morbidity and mortality rates of COPD in Saudi Arabia: Trends in burden of COPD from 1990 to 2019. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, J.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Paulson, K.R.; Gupta, V.; Abrams, E.M.; Adedoyin, R.A.; Adhikari, T.B.; Advani, S.M.; Agrawal, A.; Ahmadian, E.; et al. Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mccarthy, B.; Casey, D.; Devane, D.; Murphy, K.; Murphy, E.; Lacasse, Y. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD003793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochester, C.L.; Vogiatzis, I.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Marciniuk, D.D.; Puhan, M.A.; Spruit, M.A.; Masefield, S.; Casaburi, R.; Clini, E.M.; et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: Enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2015, 192, 1373–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahham, A.; Holland, A.E. The Need for Expanding Pulmonary Rehabilitation Services. Life 2021, 11, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, A.M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Alqahtani, K.A.; Al Rajah, A.M.; Alkhathlan, B.S.; Singh, S.J.; Mandal, S.; Hurst, J.R. Pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: A narrative review and call for further implementation in Saudi Arabia. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2021, 16, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alqarni, A.A.; Khormi, S.K.; Alwafi, H.; Samannodi, M.; Siraj, R.A.; Alhotye, M.; Naser, A.Y.; et al. Physicians’ Attitudes, Beliefs and Barriers to a Pulmonary Rehabilitation for COPD Patients in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2022, 10, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hasnaoui, A.; Rashid, N.; Lahlou, A.; Salhi, H.; Doble, A.; Nejjari, C. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the adult population within the Middle East and North Africa region: Rationale and design of the BREATHE study. Respir. Med. 2012, 106, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghobain, M. The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Saudi Arabia: Where do we stand? Ann. Thorac. Med. 2011, 6, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Moamary, M.S.; Al Ghobain, M.A.; Al Shehri, S.N.; Alfayez, A.I.; Gasmelseed, A.Y.; Al-Hajjaj, M.S. The prevalence and characteristics of water-pipe smoking among high school students in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2012, 5, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al Moamary, M.S.; Al Ghobain, M.O.; Al Shehri, S.N.; Gasmelseed, A.Y.; Al-Hajjaj, M.S. Predicting tobacco use among high school students by using the global youth tobacco survey in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2012, 7, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Waness, A.; ABU El-Sameed, Y.; Mahboub, B.; Noshi, M.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Vats, M.; Mehta, A.C. Respiratory disorders in the Middle East: A review. Respirology 2011, 16, 755–766. [Google Scholar]

- Alsubaiei, M.; Cafarella, P.; Frith, P.; McEvoy, R.D.; Effing, T.W. Factors influencing management of chronic respiratory diseases in general and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in particular in Saudi Arabia: An overview. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2018, 13, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Lázaro, D.; Santamaría, G.; Sánchez-Serrano, N.; Caeiro, E.L.; Seco-Calvo, J. Efficacy of Therapeutic Exercise in Reversing Decreased Strength, Impaired Respiratory Function, Decreased Physical Fitness, and Decreased Quality of Life Caused by the Post-COVID-19 Syndrome. Viruses 2022, 14, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soares, M.N.; Eggelbusch, M.; Naddaf, E.; Gerrits, K.H.; van der Schaaf, M.; van den Borst, B.; Wiersinga, W.J.; van Vugt, M.; Weijs, P.J.; Murray, A.J.; et al. Skeletal muscle alterations in patients with acute Covid-19 and post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumtaz, S.U. Chronic Respiratory Diseases: Innovations in Treatment and Management. Pak. J. Health Sci. 2024, 5, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Vasques, F.; Camporota, L.; Barrett, N.A. Nonantibiotic Pharmacological Treatment of Severe Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations. Semin. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020, 41, 842–850. [Google Scholar]

- Nici, L. Improving the lives of individuals with chronic respiratory disease: The need for innovation. Thorax 2022, 77, 636–637. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Q.; Jiang, D. Global trends of interstitial lung diseases from 1990 to 2019: An age–period–cohort study based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019, and projections until 2030. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1141372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijsenbeek, M.S.; Holland, A.E.; Swigris, J.J.; Renzoni, E.A. Comprehensive supportive care for patients with fibrosing interstitial lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Franssen, F.M.; Alison, J.A. Rehabilitation in chronic respiratory diseases: Live your life to the max. Respirology 2019, 24, 828–829. [Google Scholar]

- Sundar, D. Integrating psychological interventions into holistic management of chronic respiratory diseases. Int. J. Health Sci. 2024, 8, 324–333. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Shao, Y.; He, D. Advancing Treatment Strategies: A Comprehensive Review of Drug Delivery Innovations for Chronic Inflammatory Respiratory Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Cox, N.S.; Houchen-Wolloff, L.; Rochester, C.L.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Limberg, T.; Lareau, S.C.; Yawn, B.P.; et al. Defining modern pulmonary rehabilitation: An official American thoracic society workshop report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, e12–e29. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, C.-C.; Chu, W.-H.; Yang, M.-C.; Lee, C.-H.; Wu, Y.-K.; Wu, C.-P. Benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD and normal exercise capacity. Respir. Care 2013, 58, 1482–1488. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi, T.; Shingai, K.; Ichiki, K.; Jimi, T.; Kawano, T.; Kato, K.; Tsuda, T. Effects of exercise intensity on nutritional status, body composition, and energy balance in patients with COPD: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm. Med. 2025, 25, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Rochester, C.L.; Alison, J.A.; Carlin, B.; Jenkins, A.R.; Cox, N.S.; Bauldoff, G.; Bhatt, S.P.; Bourbeau, J.; Burtin, C.; Camp, P.G.; et al. Pulmonary Rehabilitation for Adults with Chronic Respiratory Disease: An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 208, E7–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, M.A.; Singh, S.J.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Rochester, C.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.E.; Lareau, S.C.; Man, W.D.-C.; et al. An official American thoracic society/European respiratory society statement: Key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, e13–e64. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, N.S.; Dal Corso, S.; Hansen, H.; McDonald, C.F.; Hill, C.J.; Zanaboni, P.; Alison, J.A.; O’Halloran, P.; Macdonald, H.; Holland, A.E. Telerehabilitation for chronic respiratory disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD013040. [Google Scholar]

- Burge, A.T.; Cox, N.S.; Holland, A.E.; McDonald, C.F.; Alison, J.A.; Wootton, R.; Hill, C.J.; Zanaboni, P.; O’halloran, P.; Bondarenko, J.; et al. Telerehabilitation Compared with Center-based Pulmonary Rehabilitation for People with Chronic Respiratory Disease: Economic Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2025, 22, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kahtani, N.; Alrawiai, S.; Al-Zahrani, B.M.; Abumadini, R.A.; Aljaffary, A.; Hariri, B.; Alissa, K.; Alakrawi, Z.; Alumran, A. Digital health transformation in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional analysis using Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society’ digital health indicators. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221117742. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. SEHA Virtual Hospital: Our Future Is Today; Saudi Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sheerah, H.A.; AlSalamah, S.; Alsalamah, S.A.; Lu, C.-T.; Arafa, A.; Zaatari, E.; Alhomod, A.; Pujari, S.; Labrique, A. The Rise of Virtual Health Care: Transforming the Health Care Landscape in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Review Article. Telemed. e-Health 2024, 30, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar]

- Alamri, H.M.; Alshagrawi, S. Factors Influencing Telehealth Adoption in Managing Healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2024, 17, 5225. [Google Scholar]

- A Alodhayani, A.; Hassounah, M.M.; Qadri, F.R.; A Abouammoh, N.; Ahmed, Z.; Aldahmash, A.M. Culture-Specific Observations in a Saudi Arabian Digital Home Health Care Program: Focus Group Discussions with Patients and Their Caregivers. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Almalki, M.; Fitzgerald, G.; Clark, M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: An overview. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2011, 17, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Saudi Ministry of Health. Annual Health Statistical Report; Saudi Ministry of Health: Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2022; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Observatory Data on Hospital Beds; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mani, Z.A.; Goniewicz, K. Transforming Healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Vision 2030’s Impact. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Annual Health Statistical Report 2023. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/Statistics/book/Documents/Statistical-Yearbook-2023.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Liu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, K. The Cost-Effectiveness of Pulmonary Rehabilitation for COPD in Different Settings: A Systematic Review. Appl. Health Econ. Health Policy 2021, 19, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khushhal, A.; Alsubaiei, M. Barriers to Establishing Outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhahir, A.M.; Alqahtani, J.S.; A AlDraiwiesh, I.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alsulayyim, A.S.; A Alqarni, A.; Alhotye, M.; Alwafi, H.; Siraj, R.; Alrajeh, A.; et al. Healthcare providers’ attitudes, beliefs and barriers to pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e063900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Moamary, M.S. Experience with pulmonary rehabilitation program in a tertiary care center in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al Moamary, M.S. Health Care Utilization among Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients and the Effect of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Med. Princ. Pract. 2010, 19, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Moamary, M.S. Impact of a pulmonary rehabilitation programme on respiratory parameters and health care utilization in patients with chronic lung diseases other than COPD. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2012, 18, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.M.; Almutairi, A.M.; Aldhahi, M.I.; Alotaibi, T.F.; AbuNurah, H.Y.; Olayan, L.H.; Aljuhani, T.K.; Alanazi, A.A.; Aldriwesh, M.G.; Alamri, H.S.; et al. The Intersection of Health Rehabilitation Services with Quality of Life in Saudi Arabia: Current Status and Future Needs. Healthcare 2023, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikman, Å.; Stenberg, G.; Lundell, S. Interprofessional collaboration in the care delivery pathway for patients with COPD—Experiences of nurses and physical therapists: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Physiother. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author and Year | Objective | Study Design | Participants’ Characteristics | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M.S. Al Moamary, 2012 [48] | To evaluate PR on health care utilization and to find factors that predict good adherence to the PR program | Retrospective study (Data were analyzed for 12 months pre- and post-pulmonary rehabilitation) | 51 patients (15 males, 36 females; mean age 57.2 years) with interstitial lung diseases, bronchiectasis, asthma, and scoliosis | -functional exercise capacity 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) improved by an average of 113 m across all patients (from 226 m to 339 m). -Healthcare utilization patterns (ER visits reduced from 2.5 to 0.9 visits per patient, outpatient clinic visits decreased from 5.3 to 2.8 visits, OCS reduced from 117 mg to 33 mg, and antibiotic use dropped from 2.0 to 0.9 courses per patient, which may help to predict the level of adherence to the PR program) -Adherent patients showed better outcomes than non-adherent ones across all metrics |

| M.S. Al Moamary, 2010 [47] | To assess the impact of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) on health care utilization and functional outcomes in COPD patients, while identifying barriers to adherence | Retrospective study | 62 patients who were diagnosed with COPD were referred to PR—50 patients enrolled; 27 (54%) were adherent and 23 (46%) non-adherent. Patients had a mean age of 66 years and a mean FEV1 of 49% | -Adherent Group: Reduced emergency department visits (2.0 to 0.8 per year), hospital stays (2.2 to 0.6 days), outpatient visits (5.3 to 2.6 per year), short-acting bronchodilator use (9.9 to 4.9), prednisone dose (379 mg to 260 mg), and antibiotic use (3.2 to 1.5 courses) -Non-Adherent Group: Increased prednisone and antibiotic use. Improvements in 6-minute walking distance (218 to 339 m) -Barriers to Adherence: 7 were hospitalized (30.4%), 3 had transportation issues (13.0%), 2 reported program intolerance (8.6%), and 11 were unspecified (47.8%) |

| M.S. Al Moamary, 2008 [46] | To present the experience of implementing the first pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) program in Saudi Arabia and assess its impact | Prospective cohort study over 30 months | 121 patients referred to PR: 89 (73.6%) attended, and 32 (26.4%) did not. Of the attendees, 51 (57.3%) adhered, and 38 (42.7%) did not complete the program. Diagnoses included COPD, bronchiectasis, chronic asthma, interstitial lung disease, and kyphoscoliosis | Significant improvements in adherent patients: Exercise Capacity: 6MWD increased from 216 ± 110 m to 544 ± 269 m; treadmill, arm ergometer, and bicycle performance significantly improved Non-Adherence Causes: Transportation issues (34.2%), hospital admission (23.7%), and unspecified reasons (42.1%) Program Feasibility: Demonstrated improvements in exercise performance and physical fitness |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alahmadi, F.H. Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions. Medicina 2025, 61, 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040673

Alahmadi FH. Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions. Medicina. 2025; 61(4):673. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040673

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlahmadi, Fahad H. 2025. "Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions" Medicina 61, no. 4: 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040673

APA StyleAlahmadi, F. H. (2025). Optimizing Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Saudi Arabia: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Directions. Medicina, 61(4), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040673