The Association Between Oral Health and the Tendencies to Obsessive–Compulsive Behavior in Biomedical Students—A Questionnaire Based Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Questionnaires

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.Y.; Watt, R.G.; Williams, D.M.; Giannobile, W.V. A New Definition for Oral Health: Implications for Clinical Practice, Policy, and Research. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamster, I.B. Defining oral health: A new comprehensive definition. Int. Dent. J. 2016, 66, 321. [Google Scholar]

- Hescot, P. The New Definition of Oral Health and Relationship between Oral Health and Quality of Life. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 20, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Skallevold, H.E.; Rokaya, N.; Wongsirichat, N.; Rokaya, D. Importance of oral health in mental health disorders: An updated review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2023, 13, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M.; Cooper, S.A.; Hughes-McCormack, L.; Macpherson, L.; Kinnear, D. Oral health of adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 1359–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kisely, S.; Sawyer, E.; Siskind, D.; Lalloo, R. The oral health of people with anxiety and depressive disorders—A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 200, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancebo, M.C.; Eisen, J.L.; Grant, J.E.; Rasmussen, S.A. Obsessive compulsive personality disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder: Clinical characteristics, diagnostic difficulties, and treatment. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 17, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Choi-Kain, L.W.; Rodriguez-Villa, A.M.; Ilagan, G.S.; Iliakis, E.A. Personality Disorders. In Introduction to Psychiatry: Preclinical Foundations and Clinical Essentials; Walker, A., Schlozman, S., Alpert, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Diedrich, A.; Voderholzer, U. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: A current review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2015, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, A.; Torrico, T.J. Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK597372/ (accessed on 15 January 2024).

- Moharrami, M.; Perez, A.; Mohebbi, S.Z.; Bassir, S.H.; Amin, M. Oral health status of individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder considering oral hygiene habits. Spec. Care Dent. 2022, 42, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura, M.; Ikeda-Nakaoka, Y.; Sasahara, H. An assessment of oral self-care level among Japanese dental hygiene students and general nursing students using the Hiroshima University--Dental Behavioural Inventory (HU-DBI): Surveys in 1990/1999. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2000, 4, 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, S.A.; Suzuki, T.; Lynam, D.R.; Crego, C.; Widiger, T.A.; Miller, J.D.; Samuel, D.B. Development and Examination of the Five-Factor Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Short Form. Assessment 2018, 25, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildiz, S.; Dogan, B. Self reported dental health attitudes and behaviour of dental students in Turkey. Eur. J. Dent. 2011, 5, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.; Teller, J.; Wheaton, M.G. Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder: A Review of Symptomatology, Impact on Functioning, and Treatment. Focus 2022, 20, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkamash, H.M.; Abuohashish, H.M. The Behavior of Patients with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Dental Clinics. Int. J. Dent. 2021, 2021, 5561690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, T.; Kelly, A.; Randall, C.L.; Tranby, E.; Franstve-Hawley, J. Association Between Mental Health and Oral Health Status and Care Utilization. Front. Oral Health 2022, 2, 732882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDI World Dental Federation. Alcohol as a Risk for Oral Health. Int. Dent. J. 2024, 74, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, K.; Sudhir, K.M.; Reddy, V.C.S.; Kumar, R.K.; Srinivasulu, G. Impact of Alcohol Dependency on Oral Health—A Cross-sectional Comparative Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC43–ZC46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicone, P.F.; Tarli, C.; Mirijello, A.; Raffaelli, L.; Vassallo, G.A.; Antonelli, M.; Rando, M.M.; Mosoni, C.; Cossari, A.; Lavorgna, L.; et al. Dental health in patients affected by alcohol use disorders: A cross-sectional study. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 21, 5021–5027. [Google Scholar]

- Çetinkaya, H.; Romaniuk, P. Relationship between consumption of soft and alcoholic drinks and oral health problems. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2020, 28, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, A.L.; Zetu, L.; Teslaru, S. Instability of self-esteem, self-confidence, self-liking, self-control, self-competence and perfectionism: Associations with oral health status and oral health-related behaviours. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2012, 10, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhong, J.; Li, H.; Pei, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Yue, Y.; Xiong, X. The relationship between perfectionism, self-perception of orofacial appearance, and mental health in college students. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1154413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisen, J.L.; Coles, M.E.; Shea, M.T.; Pagano, M.E.; Stout, R.L.; Yen, S.; Grilo, C.M.; Rasmussen, S.A. Clarifying the convergence between obsessive compulsive personality disorder criteria and obsessive compulsive disorder. J. Pers. Disord. 2006, 20, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.K.; Gan, K.Q.; Lui, W.K. The Associations between Obsessive Compulsive Personality Traits, Self-Efficacy, and Exercise Addiction. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán, M.; Simón, M.A. Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Oral Lichen Planus: A Case Study. Scand. J. Behav. Ther. 1999, 28, 143–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaigian, A.; Chaffee, B.W. Mental Health and Oral Health in a Nationally Representative Cohort. J. Dent. Res. 2023, 102, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khairunnisa, Z.; Siluvai, S.; Kanakavelan, K.; Agnes, L.; Indumathi, K.P.; Krishnaprakash, G. Mental and Oral Health: A Dual Frontier in Healthcare Integration and Prevention. Cureus 2024, 16, e76264. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, S.; Yoshimura, H. Impact of oral health management on mental health and psychological disease: A scoping review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2023, 51, 3000605221147186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komabayashi, T.; Kwan, S.Y.; Hu, D.Y.; Kajiwara, K.; Sasahara, H.; Kawamura, M. A comparative study of oral health attitudes and behaviour using the Hiroshima University—Dental Behavioural Inventory (HU-DBI) between dental students in Britain and China. J. Oral Sci. 2005, 47, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Study Sample N = 384 | Lower Tendency Toward OCPD FFOCI-SF ≤ 144 N = 206 | Higher Tendency toward OCPD FFOCI-SF > 144 N = 178 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (N, %) | ||||

| Male | 112 (29.2) | 73 (35.4) | 39 (21.9) | 0.005 * |

| Female | 272 (70.8) | 133 (64.6) | 139 (78.1) | |

| Age (years) | 23.2 ± 1.9 | 22.8 ± −2.0 | 23.4 ± 1.7 | 0.003 ‡ |

| Economic situation (N, %) | ||||

| Lower than average | 23 (6.0) | 10 (4.9) | 13 (7.3) | 0.109 # |

| Average | 270 (70.3) | 139 (67.5) | 131 (73.6) | |

| Above average | 91 (23.7) | 57 (27.7) | 34 (19.1) | |

| Study (N, %) | ||||

| Medicine | 172 (44.8) | 85 (40.8) | 66 (44.0) | 0.703 * |

| Dental medicine | 150 (39,1) | 91 (44.2) | 81 (45.5) | |

| Pharmacy | 62 (16.1) | 31 (15.0) | 31 (17.4) | |

| Study year (N, %) | ||||

| 1st | 42 (10.9) | 30 (14.6) | 12 (6.7) | 0.001 * |

| 2nd | 48 (12.5) | 37 (18.0) | 11 (6.2) | |

| 3rd | 50 (13.0) | 21 (10.2) | 29 (16.3) | |

| 4th | 56 (14.6) | 29 (14.1) | 27 (15.2) | |

| 5th | 60 (15.6) | 34 (16.5) | 26 (14.6) | |

| 6th | 128 (33.3) | 55 (26.7) | 73 (41.0) | |

| Average grade | 4.0 (3.8–4.2) | 3.9 (3.7–4.0) | 4.1 (3.8–4.2) | <0.001 † |

| Smoking (N, %) | ||||

| Yes | 118 (30.7) | 72 (35.0) | 46 (25.8) | |

| No | 266 (69.3) | 134 (65.0) | 132 (74.2) | 0.069 * |

| Alcohol consumption (N, %) | ||||

| Yes | 222 (57.8) | 139 (66.5) | 85 (47.8) | 0.003 * |

| No | 162 (42.2) | 69 (33.5) | 93 (52.2) |

| Parameter | I Don’t Agree | I Agree |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I do not worry much about visiting the dentist. | 102 (26.6) | 282 (73.4) |

| 2. My gum tends to bleed when I brush my teeth. | 362 (94.3) | 22 (5.7) |

| 3. I worry about the color of my teeth. | 220 (57.3) | 164 (42.7) |

| 4. I have noticed some white sticky deposits on my teeth. | 360 (93.7) | 24 (6.2) |

| 5. I use a child sized toothbrush. | 382 (99.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| 6. I think that I cannot help having false teeth when I am old. | 326 (84.9) | 58 (15.1) |

| 7. I am bothered by the color of my gum. | 368 (95.8) | 16 (4.2) |

| 8. I think my teeth are getting worse despite my daily brushing. | 288 (75.0) | 96 (25.0) |

| 9. I brush each of my teeth carefully. | 88 (22.9) | 296 (77.1) |

| 10. I have never been taught professionally how to brush. | 257 (66.9) | 127 (33.1) |

| 11. I think I can clean my teeth well without using toothpaste. | 319 (83.1) | 65 (16.9) |

| 12. I often check my teeth in a mirror after brushing. | 78 (20.3) | 306 (79.7) |

| 13. I worry about having bad breath. | 244 (63.5) | 140 (36.5) |

| 14. It is impossible to prevent gum disease with tooth brushing alone. | 308 (80.2) | 76 (19.8) |

| 15. I put off going to dentist until I have a toothache. | 293 (76.3) | 91 (23.7) |

| 16. I have used a dye to see how clean my teeth are. | 332 (86.5) | 52 (13.5) |

| 17. I use a toothbrush which has hard bristles. | 288 (75.0) | 96 (25.0) |

| 18. I do not feel I have brushed well unless I brush with hard strokes. | 294 (76.6) | 90 (23.4) |

| 19. I feel I sometimes take too much time to brush my teeth. | 264 (68.7) | 120 (31.2) |

| 20. I have had my dentist tell me that I brush very well. | 106 (27.7) | 278 (72.3) |

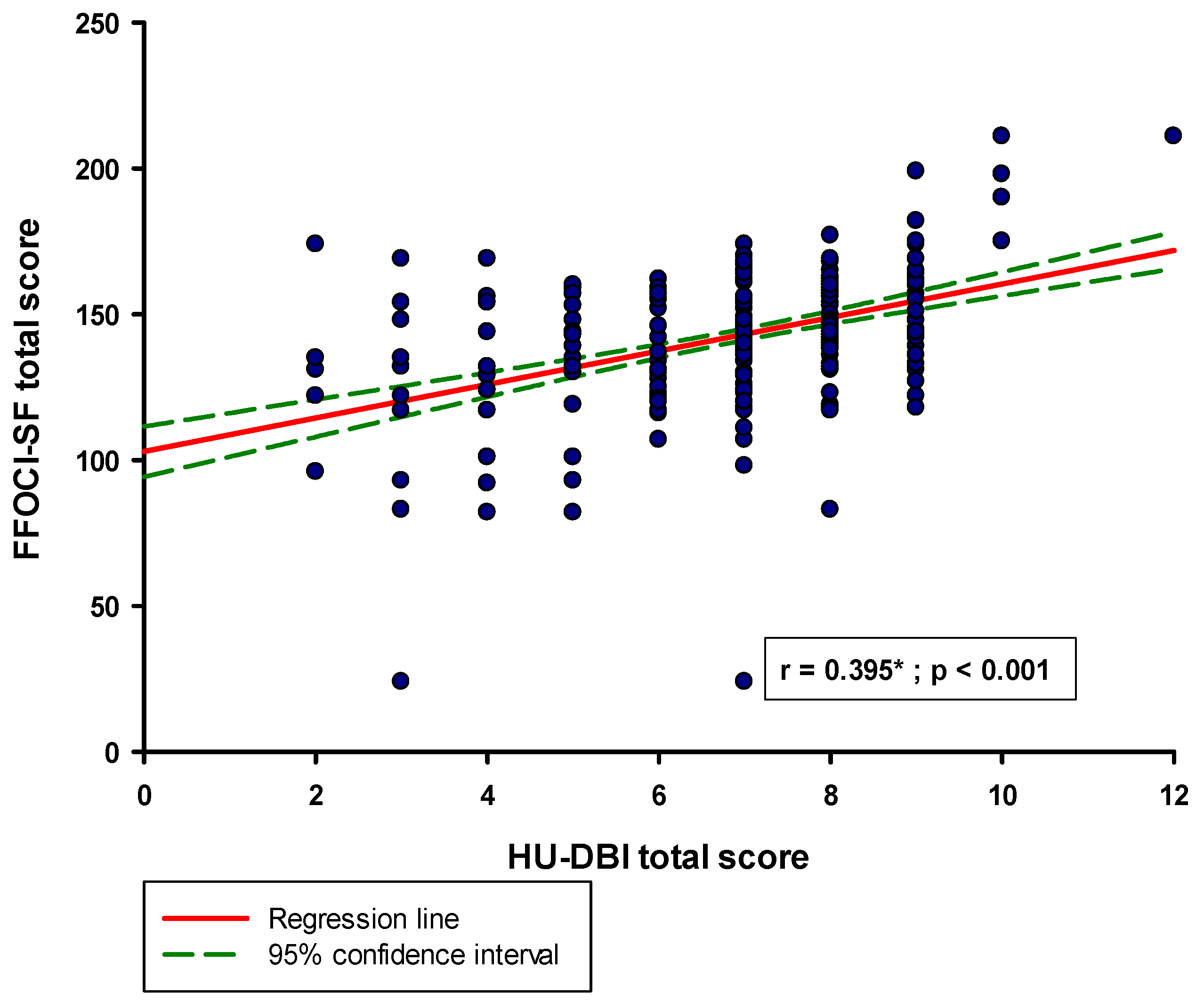

| Parameter | Study Sample N = 384 | r * | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 4.0 (3.0–4.0) | 0.223 | <0.001 |

| Attitudes | 2.0 (2.0–2.0) | 0.231 | <0.001 |

| Behavior | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 0.272 | <0.001 |

| Parameter | Study Sample N = 384 | r * | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive Worry | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 0.213 | <0.001 |

| Detached Coldness | 9.0 (7.0–11.0) | −0.013 | 0.747 |

| Risk-Aversion | 12.0 (10.0–14.0) | 0.036 | 0.474 |

| Constricted | 9.0 (8.0–11.0) | 0.044 | 0.380 |

| Inflexible | 11.5 (9.0–14.0) | 0.072 | 0.154 |

| Dogmatism | 13.0 (11.0–14.0) | 0.184 | 0.003 |

| Perfectionism | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 0.359 | <0.001 |

| Fastidiousness | 13.0 (12.0–14.0) | 0.386 | <0.001 |

| Punctiliousness | 10.5 (9.0–12.0) | 0.322 | <0.001 |

| Workaholism | 11.0 (9.0–13.0) | 0.290 | <0.001 |

| Doggedness | 11.0 (9.0–14.0) | 0.375 | <0.001 |

| Ruminative Deliberation | 14.0 (12.0–16.0) | 0.460 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinovic, D.; Cernak, M.; Lasic, S.; Puizina, E.; Lesin, A.; Rakusic, M.; Lupi-Ferandin, M.; Jurina, L.; Kulis, E.; Bozic, J. The Association Between Oral Health and the Tendencies to Obsessive–Compulsive Behavior in Biomedical Students—A Questionnaire Based Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040593

Martinovic D, Cernak M, Lasic S, Puizina E, Lesin A, Rakusic M, Lupi-Ferandin M, Jurina L, Kulis E, Bozic J. The Association Between Oral Health and the Tendencies to Obsessive–Compulsive Behavior in Biomedical Students—A Questionnaire Based Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(4):593. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040593

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinovic, Dinko, Matea Cernak, Slaven Lasic, Ema Puizina, Antonella Lesin, Mihaela Rakusic, Marino Lupi-Ferandin, Laura Jurina, Ena Kulis, and Josko Bozic. 2025. "The Association Between Oral Health and the Tendencies to Obsessive–Compulsive Behavior in Biomedical Students—A Questionnaire Based Study" Medicina 61, no. 4: 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040593

APA StyleMartinovic, D., Cernak, M., Lasic, S., Puizina, E., Lesin, A., Rakusic, M., Lupi-Ferandin, M., Jurina, L., Kulis, E., & Bozic, J. (2025). The Association Between Oral Health and the Tendencies to Obsessive–Compulsive Behavior in Biomedical Students—A Questionnaire Based Study. Medicina, 61(4), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040593