Exploring Perceptions and Experiences of Patients Undergoing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for Depression and Adjustment Disorder in Romanian Private Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Study Instrument

- Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

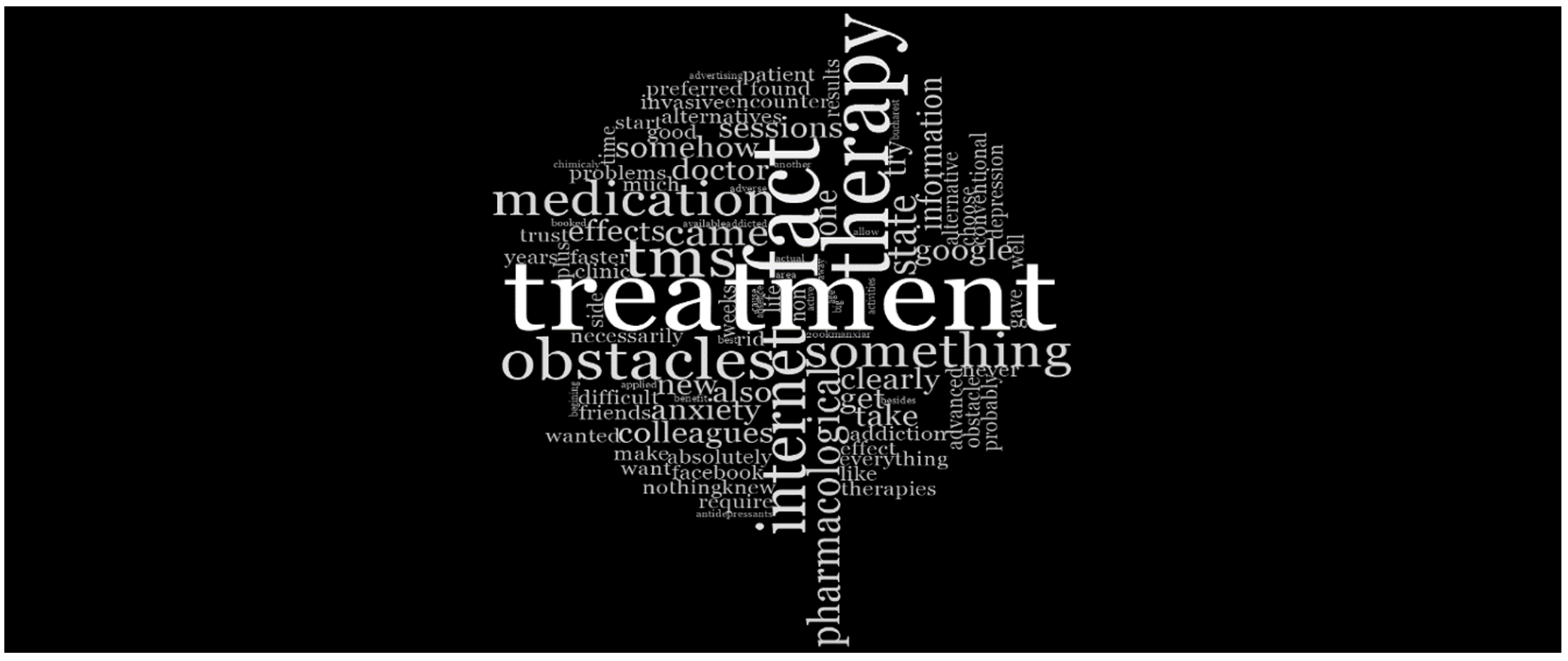

3. Results

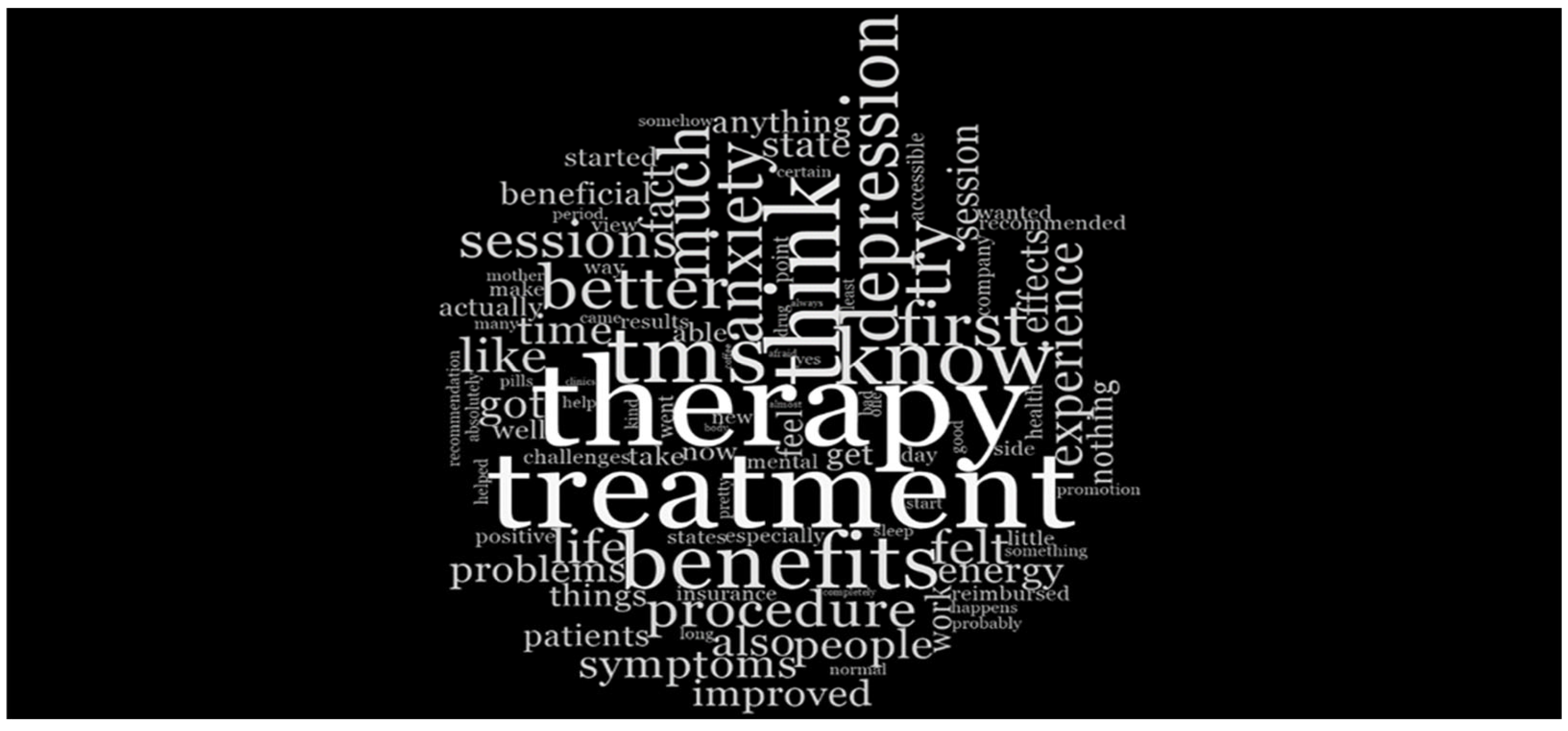

- Theme 1: Effectiveness and Acceptability of TMS

- Sub-Theme 1: Accepting TMS

“I was looking for different types of treatment because I felt vague, I had problems sleeping, I was no longer motivated, and had a lack of energy and I started looking on the Internet and I wanted to avoid drugs as much as possible because I heard that they give adverse effects or can give addiction”(P10).

“I would promote it more and propose that it be reimbursed by the National Health Insurance Fund because many people believe they would benefit from this type of treatment. It is also a more modern treatment technique with such rapid results”(P05).

- Sub-Theme 2: Effectiveness

“At first I was cautious because I had never heard of this therapy and I was a little afraid of the possible effects, how my body might react to the therapy....But in addition to some tingling in the scalp or a mild, very mild migraine that was, anyway, transient immediately after the treatment, I can say that it had a positive impact on my mental state”(P19).

“I did not experience very strong effects, but I felt the beginning of symptom relief, which helped me regain my emotional and inner balance. It was like a kind of trigger—one could call it ‘trigger therapy’”(P03).

“The decrease and disappearance of anxiety in a very large percentage, probably 90%, because everything that happens every day, if we look at them with an anxiety filter, happens badly”(P20).

“Everything that happens in a day through the filter where this anxiety is missing happens completely differently, is much better, and, after all, the end of the day is satisfactory”(P20).

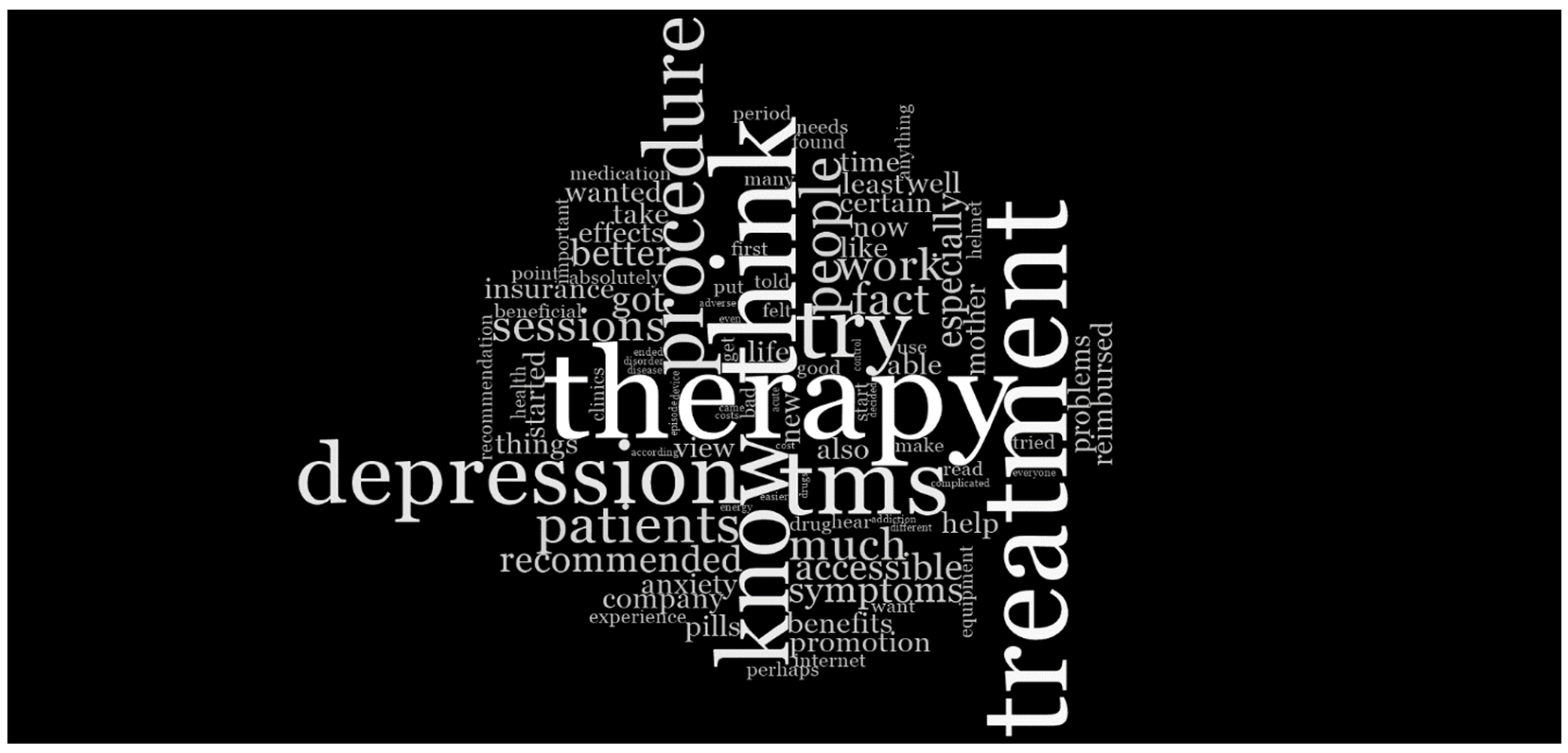

- Theme 2: Influential Factors in Deciding for TMS

“I was not willing to choose the pharmacological option. I would never have chosen pharmacological therapy to treat the symptoms. The fact that there are no side effects, that there is no risk of addiction”(P04).

“I wanted to try something that could provide fast and reliable results, that, again, does not create dependency or cause other problems. And since I read about it on the internet… I decided to give it a try”(P05).

“Being at a fairly young age, I did not want to start a conventional treatment, a medication that would require to be continued for many years. I wanted something that can be applied in the short term and that does not require years of therapy”(P19).

- The Role of Online Promotion

“The previous treatment with medication did not work, and I found the TMS therapy clinic on Facebook”(P01).

“I saw a lot of advertisements on Google and Facebook and decided that it would definitely be a good method”(P11).

“Mainly my friend, and after that, the information I found available on Google”(P12).

“Information—I searched on Google and the internet to find out what else I could do to recover”(P15).

“My colleagues, plus the internet, because I also searched about it online”(P03).

- Obstacles in Accessing TMS Treatment

“No, I did not encounter any obstacles; everything went smoothly. I started being active again, having a generally good mood, and being efficient both in carrying out my activities and in everyday life”(P01).

“As an obstacle, a significant one, though not necessarily major, was the fact that the location where I had to go for these therapies was quite far from me, and the traffic in Bucharest made it somewhat difficult for me to get to the therapy sessions. That was the only obstacle. Clearly, there were determining factors besides recommendations, and the fear of becoming dependent for life on conventional therapy somehow led me toward TMS”(P19).

“Obstacles are about distance and the fact that there are 200 km in the middle and you can’t commute every time you do TMS. My schedule, which is quite crowded, doesn’t allow me to take a few weeks off to do this treatment, but if things were to evolve and if I reached the point when I would necessarily feel the need, I would do this and I would take the same decision to start treatment with antidepressants for anxiety. So clearly, I’d go to TMS variants”(P20).

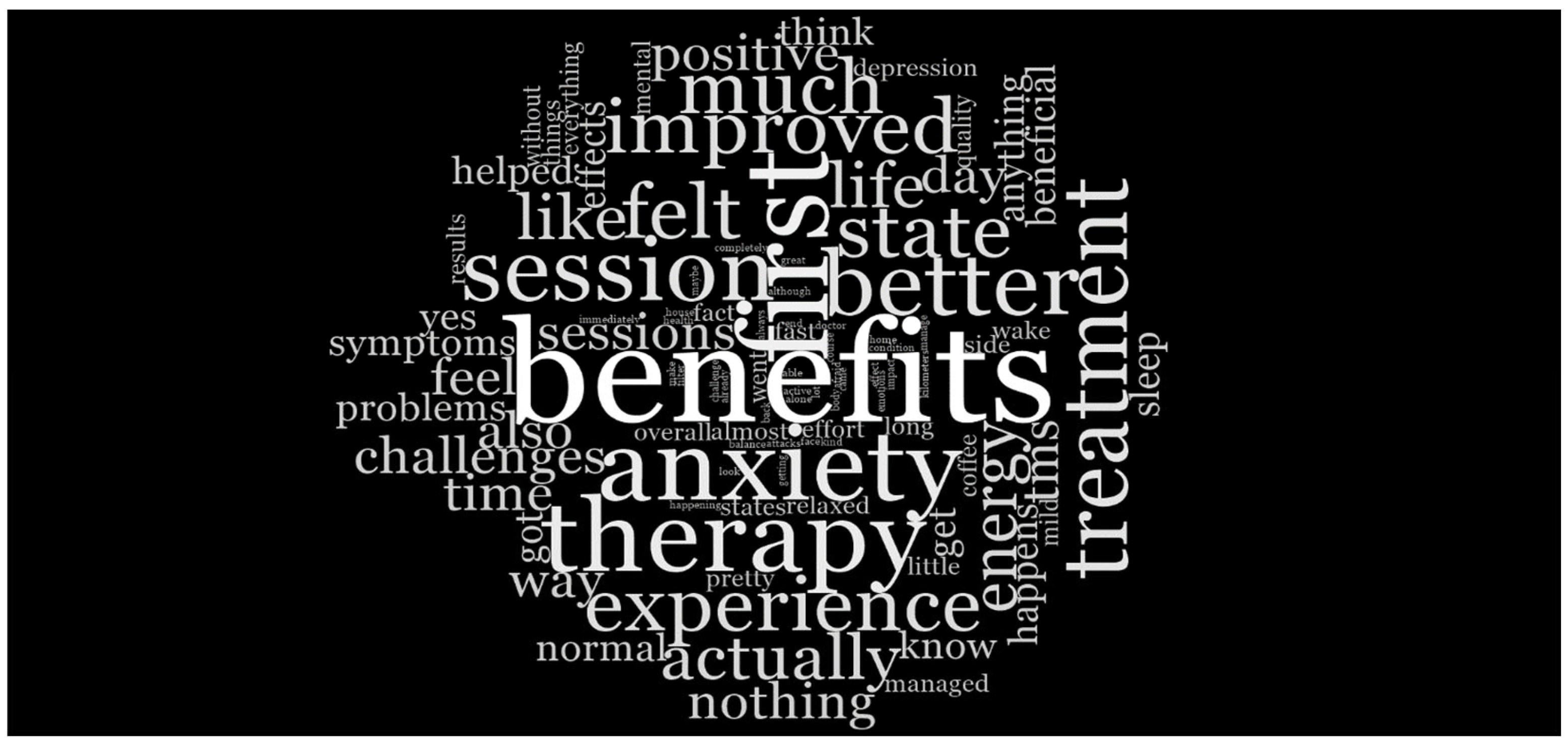

- Theme 3: TMS Compared to Other Types of Treatments

“I did not try other types of treatments because I disagree with the pills, which is why I wanted to try this variant for anxiety, and finally it solved my problem without the need to take medication”(P05).

- Negative Perceptions of Pharmacological Treatments

“I have a very good opinion from the simple fact that this therapy has no side effects compared to pharmacological treatments and overall time of therapy is shorter than for medication”(P06).

“I did not do other types of treatments, but TMS is level 99, should be part of a program, at the national level, somewhat compensated and mandatory in certain situations, because of its efficacy. It’s very relevant to me personally”(P17).

“I did not experience very strong effects, but I felt the beginning of symptom relief, which helped me regain my emotional and inner balance. It was like a kind of trigger—one could call it ‘trigger therapy’”(P03).

- Comparing the Speed and Side Effects of Medication vs. TMS

“Because of the medication, I had a state of drowsiness that affected my daily activities. With the help of rTMS, my health improved without any adverse effects”(P01).

“In the past, I took pharmacological treatment and knew that it had side effects. At that time, it seemed much more advantageous to use this non-invasive procedure”(P07).

“I have a very positive opinion simply because this therapy has no side effects compared to pharmacological treatments, and the total duration of therapy is shorter than that of medication”(P06).

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L. The Global Burden of Disease Study at 30 years. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 2019–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J.B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieling, C.; Buchweitz, C.; Caye, A.; Silvani, J.; Ameis, S.H.; Brunoni, A.R.; Cost, K.T.; Courtney, D.B.; Georgiades, K.; Merikangas, K.R.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability From Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, H.E.; Moffitt, T.E.; Copeland, W.E.; Costello, E.J.; Ferrari, A.J.; Patton, G.; Degenhardt, L.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A.; Scott, J.G. A heavy burden on young minds: The global burden of mental and substance use disorders in children and youth. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 1551–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Results. Seattle, United States: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). 2022. Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Iordache, M.M.; Sorici, C.O.; Aivaz, K.A.; Lupu, E.C.; Dumitru, A.; Tocia, C.; Dumitru, E. Depression in Central and Eastern Europe: How Much It Costs? Cost of Depression in Romania. Healthcare 2023, 11, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, J.J.; Diefenbacher, A. The adjustment disorders: The conundrums of the diagnoses. Compr. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradus, J. Prevalence and prognosis of stress disorders: A review of the epidemiologic literature. Clin. Epidemiol. 2017, 9, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaesmer, H.; Romppel, M.; Brähler, E.; Hinz, A.; Maercker, A. Adjustment disorder as proposed for ICD-11: Dimensionality and symptom differentiation. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 940–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaseen, Y.A. Adjustment disorder: Prevalence, sociodemographic risk factors, and its subtypes in outpatient psychiatric clinic. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2017, 28, 82–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, D.; Dinu, E.A.; Rogozea, L.; Burtea, V.; Leasu, F.-G. Therapeutic Interventions for Adjustment Disorder: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Ther. 2020, 27, e375–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooij, S.J.H.; Arulpragasam, A.R.; McDonald, W.M.; Philip, N.S. Accelerated TMS—Moving quickly into the future of depression treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klomjai, W.; Katz, R.; Lackmy-Vallée, A. Basic principles of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and repetitive TMS (rTMS). Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2015, 58, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.W.; Hill, A.T.; Rogasch, N.C.; Hoy, K.E.; Fitzgerald, P.B. Use of theta-burst stimulation in changing excitability of motor cortex: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 63, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanella, S.M.; Roe, D.; Paciorek, R.; Cappon, D.; Ruffini, G. Sleep, Noninvasive Brain Stimulation, and the Aging Brain: Challenges and Opportunities. Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 61, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, J.-P.; Jodoin, V.D.; Lespérance, P.; Blumberger, D.M. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for major depressive disorder: Basic principles and future directions. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 11, 20451253211042696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reardon, J.P.; Solvason, H.B.; Janicak, P.G.; Sampson, S.; Isenberg, K.E.; Nahas, Z.; McDonald, W.M.; Avery, D.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Loo, C.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in the Acute Treatment of Major Depression: A Multisite Randomized Controlled Trial. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberger, D.M.; Vila-Rodriguez, F.; Thorpe, K.E.; Feffer, K.; Noda, Y.; Giacobbe, P.; Knyahnytska, Y.; Kennedy, S.H.; Lam, R.W.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): A randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2018, 391, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuronetics. NeuroStar® Advanced Therapy for Mental Health Receives FDA Clearance for Treatment of Anxious Depression. Neuronetics. Available online: https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2022/07/19/2481621/0/en/NeuroStar-Advanced-Therapy-for-Mental-Health-Receives-FDA-Clearance-for-Treatment-of-Anxious-Depression.html (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Brainsway. BrainsWay Receives Expanded FDA Labeling to Treat Late Life Depression. Available online: https://www.brainsway.com/news_events/brainsway-receives-expanded-fda-labeling-to-treat-late-life-depression/ (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Food and Drug Administration. FDA Permits Marketing of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Treatment of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. FDA. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-transcranial-magnetic-stimulation-treatment-obsessive-compulsive-disorder (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Zangen, A.; Moshe, H.; Martinez, D.; Barnea-Ygael, N.; Vapnik, T.; Bystritsky, A.; Duffy, W.; Toder, D.; Casuto, L.; Grosz, M.L.; et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for smoking cessation: A pivotal multicenter double-blind randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry 2021, 20, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; André-Obadia, N.; Antal, A.; Ayache, S.S.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Cantello, R.M.; Cincotta, M.; de Carvalho, M.; De Ridder, D.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS): An update (2014–2018). Clin. Neurophysiol. 2020, 131, 474–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Hallett, M.; Rossini, P.M.; Pascual-Leone, A. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2009, 120, 2008–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillianesis, G.; Cavaleri, R.; Summers, S.J.; Tang, C. Exploring patient perceptions of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation as a treatment for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e058928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manescu, E.A.; Henderson, C.; Paroiu, C.R.; Mihai, A. Mental health related stigma in Romania: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, D.; Druguș, D.; Leașu, F.; Azoicăi, D.; Repanovici, A.; Rogozea, L.M. Patients’ perceptions of healthcare professionalism—A Romanian experience. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Mental Disorders Manual of Fifth Edition DSM-5. Am. Psychiatr. Publ. 2013, 17, 461–462. [Google Scholar]

- Constantin, D.A.; Monescu, V.; Cioriceanu, I.H.; Leaşu, F.G.; Rogozea, L.M. Can Medication be a Factor that Can Negatively Affect the Effect of Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation in Depression? Am. J. Ther. 2024, 31, e30–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin Dan-Alexandru. Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of rTMS (Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation)—An Emerging Public Health Issue in Adjustment and Depressive Disorders. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Medicine, Brasov, Romania, 2024.

- Carpenter, L.L.; Janicak, P.G.; Aaronson, S.T.; Boyadjis, T.; Brock, D.G.; Cook, I.A.; Dunner, D.L.; Lanocha, K.; Solvason, H.B.; Demitrack, M.A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) for major depression: A multisite, naturalistic, observational study of acute treatment outcomes in clinical practice. Depress. Anxiety 2012, 29, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlim, M.T.; Van den Eynde, F.; Daskalakis, Z.J. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the efficacy and acceptability of bilateral repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) for treating major depression. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.R.; Sockol, L.; Barber, J.P.; Moseley, M.; Lamprou, L.; Rickels, K.; O’Reardon, J.P.; Epperson, C.N. A survey of patient acceptability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) during pregnancy. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 129, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheper, A.; Rosenfeld, C.; Dubljević, V. The public impact of academic and print media portrayals of TMS: Shining a spotlight on discrepancies in the literature. BMC Med. Ethics 2022, 23, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldbloom, D.S.; Gratzer, D. Barriers to Brain Stimulation Therapies for Treatment-Resistant Depression: Beyond Cost Effectiveness. Can. J. Psychiatry 2020, 65, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.; Lankappa, S.; Burnett, M.; Khalifa, N.; Beer, C. Patients with depression who self-refer for transcranial magnetic stimulation treatment: Exploratory qualitative study. BJPsych Bull. 2018, 42, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Code | Sex | Age in years |

|---|---|---|

| P01 | F | 21 |

| P02 | F | 51 |

| P03 | F | 39 |

| P04 | F | 30 |

| P05 | F | 28 |

| P06 | F | 28 |

| P07 | F | 35 |

| P08 | F | 41 |

| P09 | F | 40 |

| P10 | F | 28 |

| P11 | F | 29 |

| P12 | F | 44 |

| P13 | F | 61 |

| P14 | F | 64 |

| P15 | F | 26 |

| P16 | F | 31 |

| P17 | M | 36 |

| P18 | M | 35 |

| P19 | F | 25 |

| P20 | F | 42 |

| Descriptive Statistic | Major Depressive Disorder | AD with Mixed Anxiety and Depressed Mood | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| N | Valid Data | 10 | 10 |

| Missing Data | 0 | 0 | |

| Mean | 42.90 | 33.00 | |

| Minimum | 21 | 25 | |

| Maximum | 64 | 44 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Constantin, D.-A.; Cioriceanu, I.-H.; Constantin, D.A.-M.; Nacu, A.-G.; Rogozea, L.M. Exploring Perceptions and Experiences of Patients Undergoing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for Depression and Adjustment Disorder in Romanian Private Practices. Medicina 2025, 61, 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040560

Constantin D-A, Cioriceanu I-H, Constantin DA-M, Nacu A-G, Rogozea LM. Exploring Perceptions and Experiences of Patients Undergoing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for Depression and Adjustment Disorder in Romanian Private Practices. Medicina. 2025; 61(4):560. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040560

Chicago/Turabian StyleConstantin, Dan-Alexandru, Ionut-Horia Cioriceanu, Daiana Anne-Marie Constantin, Andrada-Georgiana Nacu, and Liliana Marcela Rogozea. 2025. "Exploring Perceptions and Experiences of Patients Undergoing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for Depression and Adjustment Disorder in Romanian Private Practices" Medicina 61, no. 4: 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040560

APA StyleConstantin, D.-A., Cioriceanu, I.-H., Constantin, D. A.-M., Nacu, A.-G., & Rogozea, L. M. (2025). Exploring Perceptions and Experiences of Patients Undergoing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) for Depression and Adjustment Disorder in Romanian Private Practices. Medicina, 61(4), 560. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61040560