Cluster Headache Management: Evaluating Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches Among Family and Emergency Medicine Physicians

Abstract

1. Introduction

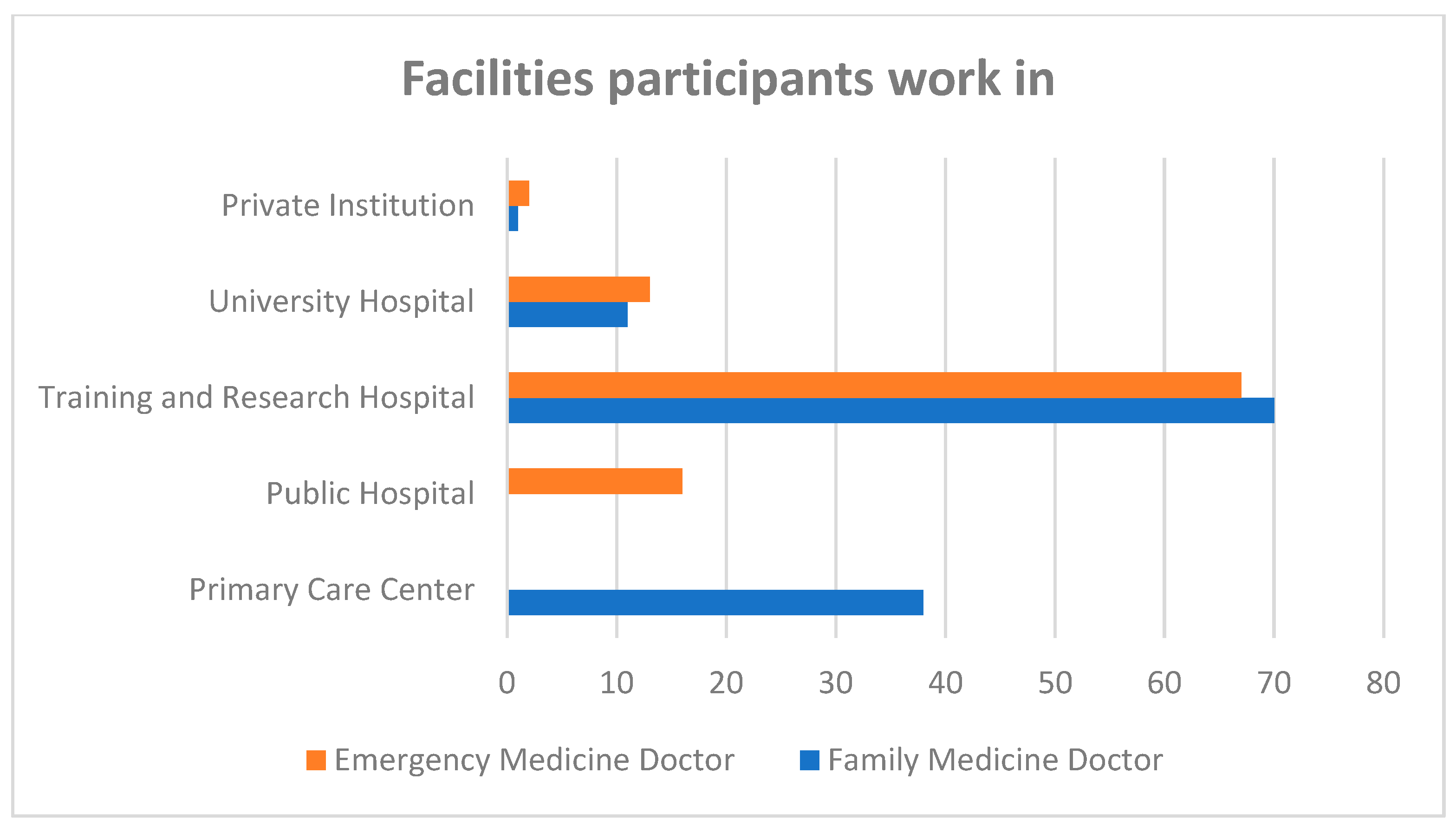

2. Method

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- San-Juan, D.; Velez-Jimenez, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Martínez-Mayorga, A.P.; Melo-Carrillo, A.; Rodríguez-Leyva, I.; García, S.; Collado-Ortiz, M.Á.; Chiquete, E.; Gudiño-Castelazo, M.; et al. Cluster headache: An update on clinical features, epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Front. Pain Res. 2024, 5, 1373528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allena, M.; De Icco, R.; Sances, G.; Ahmad, L.; Putortì, A.; Pucci, E.; Greco, R.; Tassorelli, C. Gender differences in the clinical presentation of cluster headache: A role for sexual hormones? Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, C.-A.; Lin, G.-Y.; Ting, C.-H.; Sung, Y.-F.; Lee, J.-T.; Tsai, C.-K.; Lin, Y.-K.; Ho, T.-H.; Yang, F.-C. Clinical features of cluster headache: A hospital-based study in taiwan. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 636888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.B. Epidemiology and genetics of cluster headache. Lancet Neurol. 2004, 3, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischera, M.; Marziniak, M.; Gralow, I.; Evers, S. The incidence and prevalence of cluster headache: A meta-analysis of population-based studies. Cephalalgia 2008, 28, 614–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, G.C.; Camarda, C.; Genovese, A.; Quintana, S.; Rausa, F.; Taga, A.; Torelli, P. Cluster headache in relation to different age groups. Neurol. Sci. 2019, 40, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waung, M.W.; Taylor, A.; Qualmann, K.J.; Burish, M.J. Family history of cluster headache: A systematic review. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malu, O.O.; Bailey, J.; Hawks, M.K. Cluster headache: Rapid evidence review. Am. Fam. Physician 2022, 105, 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018, 38, 1–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Andrea, G.; Gucciardi, A.; Perini, F.; Leon, A. Pathogenesis of cluster headache: From episodic to chronic form, the role of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2019, 59, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilati, L.; Torrente, A.; Alonge, P.; Vassallo, L.; Maccora, S.; Gagliardo, A.; Pignolo, A.; Iacono, S.; Ferlisi, S.; Di Stefano, V.; et al. Sleep and chronobiology as a key to understand cluster headache. Neurol. Int. 2023, 15, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, B.d.F.; Robinson, C.L.; Villar-Martinez, M.D.; Ashina, S.; Goadsby, P.J. Current and Novel Therapies for Cluster Headache: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther. 2024, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Holland, P.R.; Martins-Oliveira, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Schankin, C.; Akerman, S. Pathophysiology of migraine: A disorder of sensory processing. Physiol. Rev. 2017, 97, 553–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahra, A.; May, A.; Goadsby, P.J. Cluster headache. Neurology 2002, 58, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pringsheim, T. Cluster headache: Evidence for a disorder of circadian rhythm and hypothalamic function. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002, 29, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R.B.; Doesborg, P.G.G.; Haan, J.; Ferrari, M.D.; Fronczek, R. Pharmacotherapy for cluster headache. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji Lee, M.; Cho, S.J.; Wook Park, J.; Kyung Chu, M.; Moon, H.S.; Chung, P.W.; Myun Chung, J.; Sohn, J.H.; Kim, B.K.; Kim, B.S.; et al. Increased suicidality in patients with cluster headache. Cephalalgia 2019, 39, 1249–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Kim, B.-K.; Chung, P.-W.; Lee, M.J.; Park, J.-W.; Chu, M.K.; Ahn, J.-Y.; Song, T.-J.; Sohn, J.-H.; Oh, K.; et al. Impact of cluster headache on employment status and job burden: A prospective cross-sectional multicenter study. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, H.; Gantenbein, A.R.; Sandor, P.S.; Schoenen, J.; Andrée, C. Cluster headache and the comprehension paradox. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2022, 4, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnet, A.; Lanteri-Minet, M.; Guegan-Massardier, E.; Mick, G.; Fabre, N.; Geraud, G.; Lucas, C.; Navez, M.; Valade, D.; Société Française d’Etude des Migraines et Céphalées (SFEMC). Chronic cluster headache: A French clinical descriptive study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.L.; Snoer, A.H.; Jensen, R.H. The influence of lifestyle and gender on cluster headache. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2019, 32, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.; Petersen, A.; Snoer, A.; Jensen, R.H.; Barloese, M. Cluster headache is associated with unhealthy lifestyle and lifestyle-related comorbid diseases: Results from the Danish Cluster Headache Survey. Cephalalgia 2018, 39, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barloese, M.C.J.; Jennum, P.J.; Lund, N.T.; Jensen, R.H. Sleep in cluster headache—Beyond a temporal rapid eye movement rela-tionship? Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 656-e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barloese, M. Current understanding of the chronobiology of cluster headache and the role of sleep in its management. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2021, 13, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahra, A.; Goadsby, P.J. Diagnostic delays and mis-management in cluster headache. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2004, 109, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buture, A.; Ahmed, F.; Mehta, Y.; Paemeleire, K.; Goadsby, P.J.; Dikomitis, L. Perceptions, experiences, and understandings of cluster headache among GPs and neurologists: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e514–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-M.; Ren, L.-N.; Xu, X.-F.; Dai, Y.-L.; Jin, C.-Q.; Yang, R.-R. Cluster headache: Understandings of current knowledge and directions for whole process management. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1456517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiticovschi-Iosob, C.; Allena, M.; De Cillis, I.; Nappi, G.; Sjaastad, O.; Antonaci, F. Diagnostic and therapeutic errors in cluster headache: A hospital-based study. J. Headache Pain 2014, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Van Alboom, E.; Louis, P.; Van Zandijcke, M.; Crevits, L.; Vakaet, A.; Paemeleire, K. Diagnostic and therapeutic trajectory of cluster headache patients in Flanders. Acta Neurol. Belg. 2009, 109, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- May, A.; Schwedt, T.J.; Magis, D.; Pozo-Rosich, P.; Evers, S.; Wang, S.-J. Cluster headache. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2018, 4, 18006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollesen, A.L.H.; Snoer, A.; Beske, R.P.; Guo, S.; Hoffmann, J.; Jensen, R.H.; Ashina, M. Effect of infusion of calcitonin gene-related peptide on cluster headache attacks: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 1187–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, R.-J.; Zhu, Y.-S.; Wang, A.-P. Cluster headache due to structural lesions: A systematic review of published cases. World J. Clin. Cases 2021, 9, 3294–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakramaweera, R.; Evans, R.W.; I Schor, L.; Pearson, S.M.; Martinez, R.; Cammarata, J.S.; Amin, A.J.; Yoo, S.-H.; Zhang, W.; Yan, Y.; et al. A brief diagnostic screen for cluster headache: Creation and initial validation of the Erwin Test for Cluster Headache. Cephalalgia 2021, 41, 1298–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.Y.; Goadsby, P.J. Cluster headache pathophysiology—Insights from current and emerging treatments. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021, 17, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.S.; Starling, A.J.; Pringsheim, T.M.; Becker, W.J.; Schwedt, T.J. Treatment of Cluster Headache: The American Headache Society Evidence-Based Guidelines. Headache 2016, 56, 1093–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Jensen, R.; Katsarava, Z.; Linde, M.; MacGregor, E.A.; Osipova, V.; Paemeleire, K.; Olesen, J.; Peters, M.; Martelletti, P. Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition): On behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: The Global Campaign against Headache. J. Headache Pain 2019, 20, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nagy, A.J.; Gandhi, S.; Bhola, R.; Goadsby, P.J. Intravenous dihydroergotamine for inpatient management of refractory primary headaches. Neurology 2011, 77, 1827–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagenais, R.; Zed, P.J. Intranasal Lidocaine for Acute Management of Primary Headaches: A Systematic Review. Pharmacotherapy 2018, 38, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matharu, M.S.; Levy, M.J.; Meeran, K.; Goadsby, P.J. Subcutaneous octreotide in cluster headache: Randomized placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study. Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 488–494, Erratum in Ann. Neurol. 2004, 56, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, S.; Rapoport, A. The use of oxygen in cluster headache treatment worldwide—A survey of the International Headache Society (IHS). Cephalalgia 2016, 37, 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirkx, T.H.T.; Haane, D.Y.P.; Koehler, P.J. Oxygen treatment for cluster headache attacks at different flow rates: A double-blind, randomized, crossover study. J. Headache Pain 2018, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.S.; Lund, N.; Jensen, R.H.; Barloese, M. Real-life treatment of cluster headache in a tertiary headache center—Results from the Danish Cluster Headache Survey. Cephalalgia 2020, 41, 333102420970455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, N.L.T.; Petersen, A.S.; Fronczek, R.; Tfelt-Hansen, J.; Belin, A.C.; Meisingset, T.; Tronvik, E.; Steinberg, A.; Gaul, C.; Jensen, R.H. Current treatment options for cluster headache: Limitations and the unmet need for better and specific treatments—A consensus article. J. Headache Pain 2023, 24, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hasırcı Bayır, B.R.; Gürsoy, G.; Sayman, C.; Yüksel, G.A.; Çetinkaya, Y. Greater occipital nerve block is an effective treat-ment method for primary headaches? Agri 2022, 34, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, A.; Roe, T.; Villar-Martínez, M.D.; Moreno-Ajona, D.; Goadsby, P.J.; Hoffmann, J. Effectiveness and safety profile of greater occipital nerve blockade in cluster headache: A systematic review. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2023, 95, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orvin, C.A.; Zaheri, S.C.; Perilloux, D.M.; Field, E.; Ahmadzadeh, S.; Shekoohi, S.; Kaye, A.D. Divalproex, Valproate, & Developing Treatment Options for Cluster Headache Prophylaxis: Clinical Practice Considerations. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2024, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; D’amico, D.; Frediani, F.; Moschiano, F.; Grazzi, L.; Attanasio, A.; Bussone, G. Verapamil in the prophylaxis of episodic cluster headache: A double-blind study versus placebo. Neurology 2000, 54, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, J.N.; Engel, H.O. Individualizing Treatment with Verapamil for Cluster Headache Patients. Headache 2004, 44, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.-P.; Burish, M.J. Management of cluster headache: Treatments and their mechanisms. Cephalalgia 2023, 43, 3331024231196808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolova, V.L.; Pattanaseri, K.; Hidalgo-Mazzei, D.; Taylor, D.; Young, A.H. Is lithium monitoring NICE? Lithium monitoring in a UK secondary care setting. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, M.; Dodick, D.; Rigamonti, A.; D’Amico, D.; Grazzi, L.; Mea, E.; Bussone, G. Topiramate in Cluster Headache Prophylaxis: An Open Trial. Cephalalgia 2003, 23, 1001–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steiner, T.J.; Jensen, R.; Katsarava, Z.; Linde, M.; MacGregor, E.A.; Osipova, V.; Paemeleire, K.; Olesen, J.; Peters, M.; Martelletti, P. Hellenic Headache Society Recommendations for the Use of Monoclonal Antibodies Targeting the Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide Pathway for the Prevention of Migraine and Cluster Headache—2023 Update. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2023, 5, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.L.; Millán-Vázquez, M.; González-Oria, C. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab as chronic cluster headache preventive treatment under real world conditions: Observational prospective study. Cephalalgia 2024, 44, 3331024231226181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goadsby, P.J.; Dodick, D.W.; Leone, M.; Bardos, J.N.; Oakes, T.M.; Millen, B.A.; Zhou, C.; Dowsett, S.A.; Aurora, S.K.; Ahn, A.H.; et al. Trial of galcanezumab in prevention of episodic cluster headache. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyriou, A.A.; Vikelis, M.; Mantovani, E.; Litsardopoulos, P.; Tamburin, S. Recently available and emerging therapeutic strategies for the acute and prophylactic management of cluster headache: A systematic review and expert opinion. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2020, 21, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Membrilla, J.A.; Torres-Ferrus, M.; Alpuente, A.; Caronna, E.; Pozo-Rosich, P. Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab as a treatment of refractory episodic and chronic cluster headache: Case series and narrative review. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2022, 62, 1395–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenberg, R.; Gaul, C.; Stroud, C.E.; Dong, Y.; Bangs, M.E.; Wenzel, R.; Martinez, J.M.; Oakes, T.M. Long-term open-label safety study of galcanezumab in patients with episodic or chronic cluster headache. Cephalalgia 2022, 42, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, H.; Kim, B.K.; Moon, H.S.; Cho, S.J. Real-world experience with 240 mg of galcanezumab for the preventive treatment of cluster headache. J. Headache Pain 2022, 23, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsikostas, D.D.; Ashina, M.; Craven, A.; Diener, H.C.; Goadsby, P.J.; Ferrari, M.D.; Lampl, C.; Paemeleire, K.; Pascual, J.; Siva, A.; et al. European headache federation consensus on technical investigation for primary headache disorders. J. Headache Pain 2015, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panel on Neurologic Imaging. Whitehead, M.T.; Cardenas, A.M.; Corey, A.S.; Policeni, B.; Burns, J.; Chakraborty, S.; Crowley, R.W.; Jabbour, P.; Ledbetter, L.N.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Headache. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2019, 16, S364–S377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.Y.; Khalil, M.; Goadsby, P.J. Managing cluster headache. Pract. Neurol. 2019, 19, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Statement | Answer | FM Group n: 120 (%) | EM Group n: 98 (%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHs are a primary headache disorder | Yes | 116 (96.7) | 93 (94.9) | NS |

| No | 4 (3.3) | 5 (4.1) | ||

| CHs are a subtype or variant of migraine | Yes | 11 (9.2) | 6 (6.1) | NS |

| No | 109 (90.8) | 92 (93.9) | ||

| Localization of CH | Unilateral | 87 (72.5) | 71 (72.4) | NS |

| Bilateral | 33 (27.5) | 27 (27.6) | ||

| CH attacks usually last | 1–600 s | 14 (11.7) | 19 (19.4) | NS |

| 15–180 min | 66 (55.0) | 51 (52) | ||

| 4–72 h | 40 (33.3) | 28 (28.6) | ||

| Severity of headache | Moderate | 39 (32.5) | 31 (31.6) | NS |

| Severe | 81 (67.5) | 67 (68.4) | ||

| Gender predominance | Male | 61 (50.8) | 56 (57.1) | NS |

| Female | 59 (49.2) | 42 (42.9) | ||

| ‘CH episodes usually occur at the same time of the year.’ | True | 77 (64.2) | 65 (66.3) | NS |

| False | 10 (8.3) | 5 (5.1) | ||

| Not sure | 33 (27.5) | 28 (28.6) | ||

| ‘For the diagnosis of CH, autonomic findings must always be present, and these findings should be ipsilateral and simultaneous with the pain.’ | True | 53 (44.2) | 35 (35.7) | 0.033 * |

| False | 49 (40.8) | 34 (34.7) | ||

| Not sure | 18 (15.0) | 29 (29.6) | ||

| ‘The most common autonomic findings accompanying CH are lacrimation and conjunctival hyperemia.’ | True | 88 (73.3) | 72 (73.5) | NS |

| False | 8 (6.7) | 5 (5.1) | ||

| Not sure | 24 (20.0) | 21 (21.4) | ||

| ‘Even if it presents as typical episodic CH, neuroimaging is recommended for every patient with CH.’ | True | 61 (50.8) | 29 (29.6) | 0.002 * |

| False | 35 (29.2) | 50 (51.0) | ||

| Not sure | 24 (20.0) | 19 (19.4) | ||

| ‘Paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective in CH.’ | True | 56 (46.7) | 54 (55.1) | NS |

| False | 54 (45.0) | 31 (31.6) | ||

| Not sure | 10 (8.3) | 13 (13.3) | ||

| ‘During a CH attack, 100% oxygen therapy is administered via a face mask for 15–20 min, at a flow rate of 7–12 L per minute.’ | True | 83 (69.2) | 70 (45.8) | NS |

| False | 8 (6.7) | 7 (7.1) | ||

| Not sure | 29 (24.2) | 21 (21.4) | ||

| ‘Smoking and alcohol are the most important triggers of CH.’ | True | 68 (56.7) | 53 (54.1) | NS |

| False | 16 (13.3) | 10 (10.2) | ||

| Not sure | 36 (30.0) | 35 (35.7) |

| Statement | Answer | FM Group n: 120 (%) | EM Group n: 98 (%) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I can easily recognize CH patients in my daily practice. | Agree | 60 (50.0%) | 40 (40.8%) | 0.029 * |

| Disagree | 16 (13.3%) | 6 (6.1%) | ||

| Not sure | 44 (36.7%) | 52 (53.1%) | ||

| I can inform a patient with a suspected CH diagnosis about the necessary steps to take. | Agree | 75 (62.5%) | 63 (64.3%) | NS |

| Disagree | 11 (9.2%) | 7 (7.1%) | ||

| Not sure | 34 (28.3%) | 28 (28.6%) | ||

| A patient with CH must be referred to Neurology. | Agree | 91 (75.8%) | 89 (90.8%) | 0.008 * |

| Disagree | 10 (8.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | ||

| Not sure | 19 (15.8%) | 8 (8.2%) | ||

| When encountering a patient with CH, I worry about possibly overlooking another diagnosis. | Agree | 93 (77.5%) | 61 (62.2%) | 0.029 * |

| Disagree | 5 (4.2%) | 11 (11.2%) | ||

| Not sure | 22 (18.3%) | 26 (26.5%) | ||

| I am well-versed in acute attack treatments for cluster headache patients and can guide them appropriately. | Agree | 51 (42.5%) | 50 (51.0%) | 0.003 * |

| Disagree | 29 (24.2%) | 7 (7.1%) | ||

| Not sure | 40 (33.3%) | 41 (41.8%) | ||

| I have adequate knowledge about CH. | Agree | 15 (12.5%) | 18 (18.4%) | 0.006 * |

| Disagree | 60 (50.0%) | 28 (28.6%) | ||

| Not sure | 45 (37.5%) | 52 (53.1%) | ||

| It would make me feel more confident to have a better understanding of CH. | Agree | 107 (89.2%) | 83 (84.7%) | NS |

| Disagree | 2 (1.7%) | 6 (6.1%) | ||

| Not sure | 11 (9.2%) | 9 (9.2%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasirci Bayir, B.R.; Nazli, E.; Ulutas, C. Cluster Headache Management: Evaluating Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches Among Family and Emergency Medicine Physicians. Medicina 2025, 61, 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030437

Hasirci Bayir BR, Nazli E, Ulutas C. Cluster Headache Management: Evaluating Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches Among Family and Emergency Medicine Physicians. Medicina. 2025; 61(3):437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030437

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasirci Bayir, Buse Rahime, Ezgi Nazli, and Can Ulutas. 2025. "Cluster Headache Management: Evaluating Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches Among Family and Emergency Medicine Physicians" Medicina 61, no. 3: 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030437

APA StyleHasirci Bayir, B. R., Nazli, E., & Ulutas, C. (2025). Cluster Headache Management: Evaluating Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches Among Family and Emergency Medicine Physicians. Medicina, 61(3), 437. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61030437