Understanding Anxiety Symptoms of Mood Disorders Across Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder Using Network Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Ethical Statement

2.2. Measurements

Beck Anxiety Inventory

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

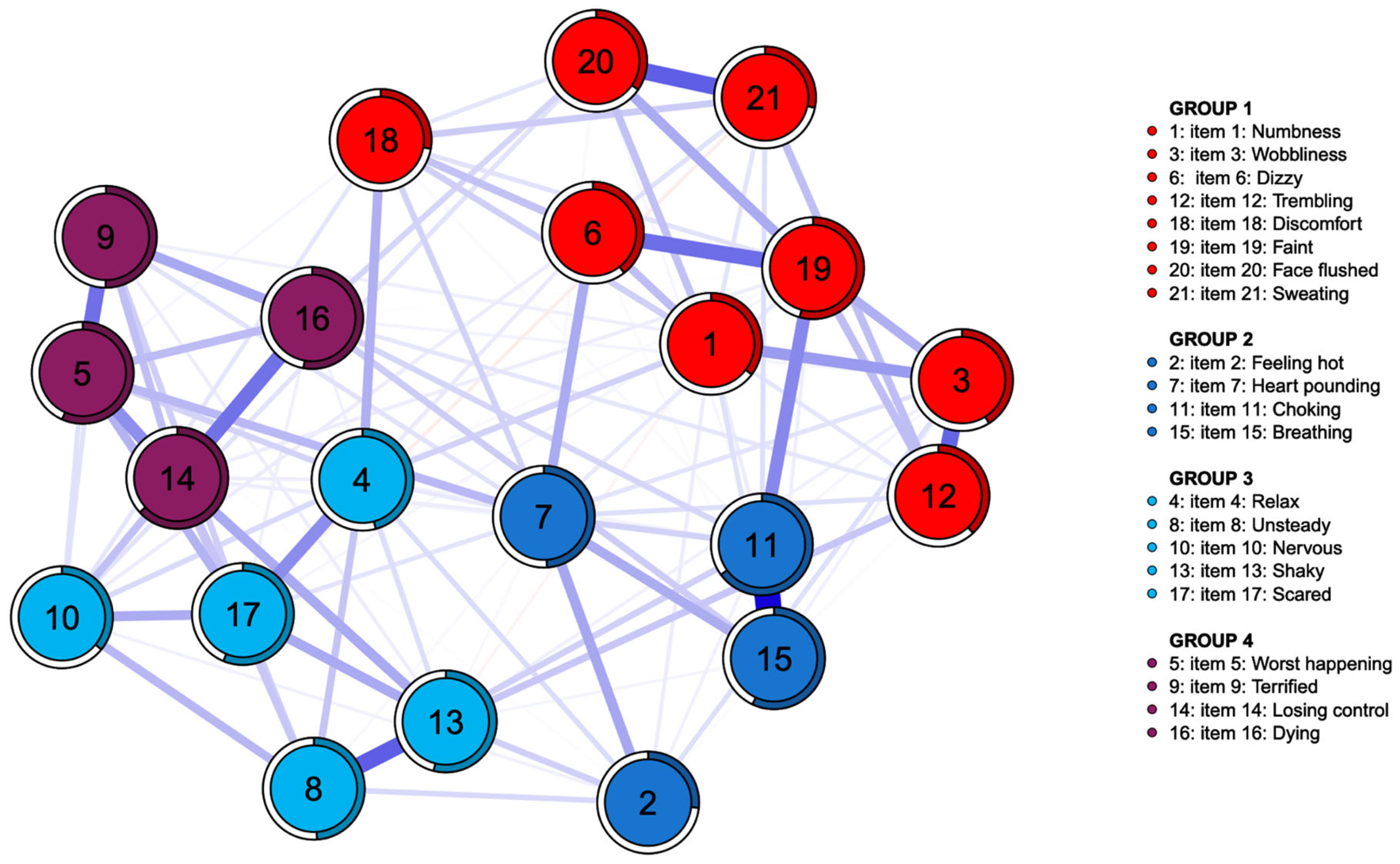

3.2. Network and Community Estimation

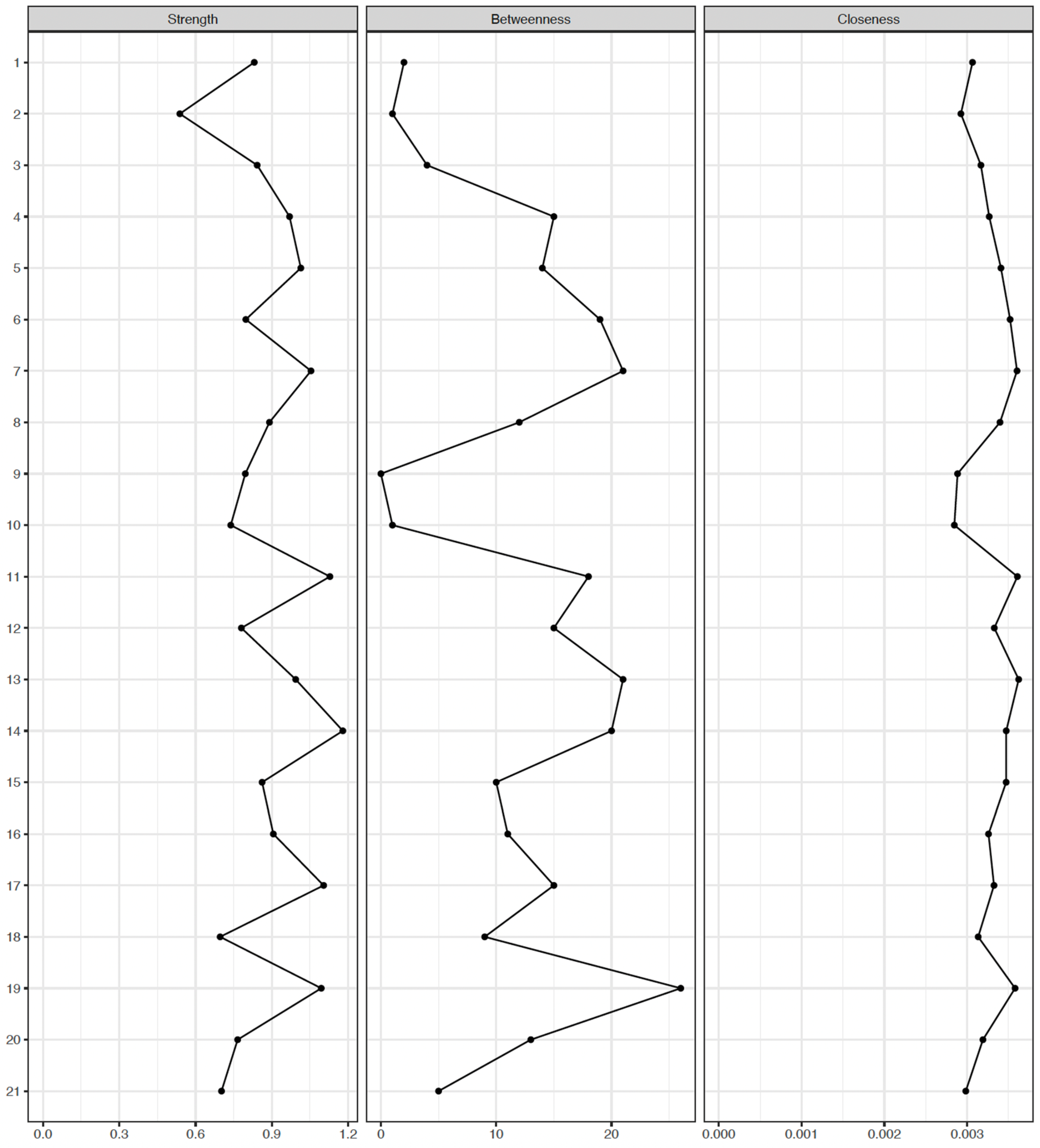

3.3. Centrality Indices and Edge Weights

3.4. Network Stability

3.5. Network Comparisons

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McIntyre, R.S.; Soczynska, J.K.; Cha, D.S.; Woldeyohannes, H.O.; Dale, R.S.; Alsuwaidan, M.T.; Gallaugher, L.A.; Mansur, R.B.; Muzina, D.J.; Carvalho, A.; et al. The prevalence and illness characteristics of DSM-5-defined “mixed feature specifier” in adults with major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder: Results from the International Mood Disorders Collaborative Project. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 172, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Nesse, R.M. Depression sum-scores don’t add up: Why analyzing specific depression symptoms is essential. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angst, F.; Stassen, H.H.; Clayton, P.J.; Angst, J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: Follow-up over 34–38 years. J. Affect. Disord. 2002, 68, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zazula, R.; Mohebbi, M.; Dodd, S.; Dean, O.M.; Berk, M.; Vargas, H.O.; Nunes, S.O.V. Cognitive profile and relationship with quality of life and psychosocial functioning in mood disorders. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2022, 37, 376–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakostas, G.I.; Petersen, T.; Mahal, Y.; Mischoulon, D.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Fava, M. Quality of life assessments in major depressive disorder: A review of the literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2004, 26, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthenelli, R.M. Focus on: Comorbid mental health disorders. Alcohol Res. Health 2010, 33, 109–117. [Google Scholar]

- Üçok, A.; Karaveli, D.; Kundakçi, T.; Yazici, O. Comorbidity of personality disorders with bipolar mood disorders. Compr. Psychiatry 1998, 39, 72–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineka, S.; Watson, D.; Clark, L.A. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1998, 49, 377–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerevanian, B.I.; Koek, R.J.; Ramdev, S. Anxiety disorders comorbidity in mood disorder subgroups: Data from a mood disorders clinic. J. Affect. Disord. 2001, 67, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, R.C.; Sampson, N.A.; Berglund, P.; Gruber, M.J.; Al-Hamzawi, A.; Andrade, L.; Bunting, B.; Demyttenaere, K.; Florescu, S.; De Girolamo, G.; et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2015, 24, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.M.; Otto, M.W.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Fossey, M.; Sagduyu, K.; Frank, E.; Sachs, G.S.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Thase, M.E.; Pollack, M.H. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am. J. Psychiatry 2004, 161, 2222–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Ormel, J.; Petukhova, M.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Green, J.G.; Russo, L.J.; Stein, D.J.; Zaslavsky, A.M.; Aguilar-Gaxiola, S.; Alonso, J.; et al. Development of lifetime comorbidity in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2011, 68, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niles, A.N.; Dour, H.J.; Stanton, A.L.; Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Stein, M.B.; Sullivan, G.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Rose, R.D.; Craske, M.G. Anxiety and depressive symptoms and medical illness among adults with anxiety disorders. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalin, N.H. The critical relationship between anxiety and depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K.R.; Akiskal, H.S.; Angst, J.; Greenberg, P.E.; Hirschfeld, R.M.; Petukhova, M.; Kessler, R.C. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2007, 64, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O.; Kalis, A. Brain disorders? Not really: Why network structures block reductionism in psychopathology research. Behav. Brain Sci. 2019, 42, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullarkey, M.C.; Marchetti, I.; Beevers, C.G. Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of adolescent depression. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, M.J.; Schneck, C.D.; Miklowitz, D.J. Network analysis of mood symptoms in adolescents with or at high risk for bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2020, 22, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, C.; Sundquist, K.; Winkleby, M.A.; Sundquist, J. Comorbidities and mortality in bipolar disorder: A Swedish national cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringmann, L.F.; Elmer, T.; Epskamp, S.; Krause, R.W.; Schoch, D.; Wichers, M.; Wigman, J.T.; Snippe, E. What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2019, 128, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-C.; Kim, D. The centrality of depression and anxiety symptoms in major depressive disorder determined using a network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 271, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McElroy, E.; Fearon, P.; Belsky, J.; Fonagy, P.; Patalay, P. Networks of depression and anxiety symptoms across development. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birkeland, M.S.; Greene, T.; Spiller, T.R. The network approach to posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1700614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, E.I.; Epskamp, S.; Nesse, R.M.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Borsboom, D. What are’good’depression symptoms? Comparing the centrality of DSM and non-DSM symptoms of depression in a network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 189, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Li, B.; Fan, X.; Chen, H.; Dang, Z.; Li, Z. A network analysis study of anxiety, depression and loneliness among middle-aged and elderly people in Xining area. BMC Psychol. 2025, 13, 931. [Google Scholar]

- Steer, R.A.; Ranieri, W.F.; Beck, A.T.; Clark, D.A. Further evidence for the validity of the Beck Anxiety Inventory with psychiatric outpatients. J. Anxiety Disord. 1993, 7, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, C.E.; Moss, T.G.; Harris, A.L.; Edinger, J.D.; Krystal, A.D. Should we be anxious when assessing anxiety using the Beck Anxiety Inventory in clinical insomnia patients? J. Psychiatr. Res. 2011, 45, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1998, 59, 22–33. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-K.; Lee, E.-H.; Hwang, S.-T.; Hong, S.-H.; Kim, J.-H. Psychometric properties of the Beck Anxiety Inventory in the community-dwelling sample of Korean adults. Korean J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 35, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabacoff, R.I.; Segal, D.L.; Hersen, M.; Van Hasselt, V.B. Psychometric properties and diagnostic utility of the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory with older adult psychiatric outpatients. J. Anxiety Disord. 1997, 11, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.; Park, K.; Yoon, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, Y.Y.; Choi, K.-H. Clinical utility of Beck Anxiety Inventory in clinical and nonclinical Korean samples. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, S.; Jiang, X.; Yu, H.; Ding, S.; Lu, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, B.; Cui, Y.; et al. Common and specific functional activity features in schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S.; Waldorp, L.J.; Mõttus, R.; Borsboom, D. The Gaussian graphical model in cross-sectional and time-series data. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2018, 53, 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Sparse inverse covariance estimation with the graphical lasso. Biostatistics 2008, 9, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Z. Extended Bayesian information criteria for model selection with large model spaces. Biometrika 2008, 95, 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behav. Res. Methods 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H.F.; Epskamp, S. Exploratory graph analysis: A new approach for estimating the number of dimensions in psychological research. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.; Golino, H. Estimating the stability of the number of factors via Bootstrap Exploratory Graph Analysis: A tutorial. PsyArXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H.; Shi, D.; Christensen, A.P.; Garrido, L.E.; Nieto, M.D.; Sadana, R.; Thiyagarajan, J.A.; Martinez-Molina, A. Investigating the performance of exploratory graph analysis and traditional techniques to identify the number of latent factors: A simulation and tutorial. Psychol. Methods 2020, 25, 292–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondel, V.D.; Guillaume, J.-L.; Lambiotte, R.; Lefebvre, E. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2008, 2008, P10008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, N.; Kang, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Yang, B.; Li, R.; Xiang, D.; et al. Using network analysis to identify central symptoms of college students’ mental health. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 311, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.P.; Golino, H. Estimating the stability of psychological dimensions via bootstrap exploratory graph analysis: A Monte Carlo simulation and tutorial. Psych 2021, 3, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golino, H.; Christensen, A.P.; Moulder, R. EGAnet: Exploratory Graph Analysis: A Framework for Estimating the Number of Dimensions in Multivariate Data Using Network Psychometrics. R Package Version 0.9. 2020, Volume 5. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=EGAnet (accessed on 17 January 2024).

- Fried, E.I.; Boschloo, L.; Van Borkulo, C.D.; Schoevers, R.A.; Romeijn, J.-W.; Wichers, M.; De Jonge, P.; Nesse, R.M.; Tuerlinckx, F.; Borsboom, D. Commentary: “Consistent superiority of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors over placebo in reducing depressed mood in patients with major depression”. Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Borkulo, C.D.; van Bork, R.; Boschloo, L.; Kossakowski, J.J.; Tio, P.; Schoevers, R.A.; Borsboom, D.; Waldorp, L.J. Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychol. Methods 2023, 28, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zung, W.W. How normal is depression? Psychosom. J. Consult. Liaison Psychiatry 1972, 13, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom, D.; Cramer, A.O.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Epskamp, S.; Waldorp, L.J. The small world of psychopathology. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I. Problematic assumptions have slowed down depression research: Why symptoms, not syndromes are the way forward. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.-N.; Chen, Y.-H.; Yan, W.-J. A network analysis of difficulties in emotion regulation, anxiety, and depression for adolescents in clinical settings. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2023, 17, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, D.; Montgomery, W.; Aguado, J.; Kadziola, Z.; Peng, X.; Brugnoli, R.; Haro, J.M. Which somatic symptoms are associated with an unfavorable course in Asian patients with major depressive disorder? J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhuis, E.; Boschloo, L.; Rosmalen, J.G.; Schoevers, R.A. Differential associations of specific depressive and anxiety disorders with somatic symptoms. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohman, H.; Jonsson, U.; Von Knorring, A.L.; Von Knorring, L.; Päären, A.; Olsson, G. Somatic symptoms as a marker for severity in adolescent depression. Acta Paediatr. 2010, 99, 1724–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, J.N.; Dryman, M.T.; Morrison, A.S.; Gilbert, K.E.; Heimberg, R.G.; Gruber, J. Positive and negative affect as links between social anxiety and depression: Predicting concurrent and prospective mood symptoms in unipolar and bipolar mood disorders. Behav. Ther. 2017, 48, 820–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corponi, F.; Anmella, G.; Verdolini, N.; Pacchiarotti, I.; Samalin, L.; Popovic, D.; Azorin, J.-M.; Angst, J.; Bowden, C.L.; Mosolov, S.; et al. Symptom networks in acute depression across bipolar and major depressive disorders: A network analysis on a large, international, observational study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 35, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, T.; Herzog, P.; Voderholzer, U.; Brakemeier, E.L. Unraveling the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in a large inpatient sample: Network analysis to examine bridge symptoms. Depress. Anxiety 2021, 38, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, C.; Millner, A.J.; Forgeard, M.J.; Fried, E.I.; Hsu, K.J.; Treadway, M.T.; Leonard, C.V.; Kertz, S.; Björgvinsson, T. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptom relationships in a psychiatric sample. Psychol. Med. 2016, 46, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platania, G.A.; Savia Guerrera, C.; Sarti, P.; Varrasi, S.; Pirrone, C.; Popovic, D.; Ventimiglia, A.; De Vivo, S.; Cantarella, R.A.; Tascedda, F.; et al. Predictors of functional outcome in patients with major depression and bipolar disorder: A dynamic network approach to identify distinct patterns of interacting symptoms. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0276822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, R.O., Jr.; Tandon, N.; Masters, G.A.; Margolis, A.; Cohen, B.M.; Keshavan, M.; Öngür, D. Differential brain network activity across mood states in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2017, 207, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, R.J. Anxiety sensitivity and panic disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2002, 52, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, A.S.; Mortensen, E.L.; Mors, O. The structure of emotional and cognitive anxiety symptoms. J. Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlattani, T.; Cavatassi, A.; Bologna, A.; Socci, V.; Trebbi, E.; Malavolta, M.; Rossi, A.; Martiadis, V.; Tomasetti, C.; De Berardis, D.; et al. Glymphatic system and psychiatric disorders: Need for a new paradigm? Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1642605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Total Sample (n = 815) Mean ± SD, n or % | MDD (n = 332) Mean ± SD, n or % | BD (n = 483) Mean ± SD, n or % | Test Statistics | Bonferroni Corrected p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 34.85 ± 12.66 | 38.53 ± 13.26 | 32.34 ± 11.59 | 7.0452 | <0.001 *** |

| Gender (%) | 1.25 | 1.00 | |||

| Male | 29.3 | 31.6 | 27.7 | ||

| Female | 70.7 | 68.4 | 72.3 | ||

| Education (%) | 1.10 | 1.00 | |||

| High school or below | 29.4 | 31.6 | 28.0 | ||

| Others | 70.6 | 68.4 | 72.0 | ||

| Employment status (%) | 0.33 | 1.00 | |||

| Unemployed | 63.7 | 62.3 | 64.6 | ||

| Employed | 36.3 | 37.7 | 35.4 | ||

| Marital status (%) | 21.0294 | <0.001 *** | |||

| Married | 35.5 | 44.9 | 29.0 | ||

| Others (Single, divorced, or widowed) | 64.5 | 55.1 | 71.0 | ||

| Alcohol use status (%) | 6.2666 | 0.098 | |||

| Former or current | 55.7 | 50.3 | 59.4 | ||

| Never | 44.3 | 49.7 | 40.6 | ||

| Smoking status (%) | 3.0244 | 0.656 | |||

| Past or current | 28.5 | 25.0 | 30.8 | ||

| Never | 71.5 | 75.0 | 69.2 | ||

| Psychiatric familial history | 44.8 | 33.7 | 52.4 | 26.9147 | <0.001 *** |

| Zung Self rating depression scale score | 55.28 ± 9.00 | 54.92 ± 9.58 | 55.53 ± 8.58 | −0.93669 | 1.00 |

| Range (n) | |||||

| <50 | 208 | 99 | 109 | ||

| 50 ≤ x < 60 | 310 | 115 | 195 | ||

| 60 ≤ x < 70 | 270 | 107 | 163 | ||

| ≥70 | 27 | 11 | 16 |

| Items | Mean (SD) | U_Statistic | p-Value | Bonferroni Corrected | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD (n = 332) | BD (n = 483) | p-Value | ||||

| 1 | Numbness or tingling | 1.16 (0.98) | 1.06 (0.95) | 84,790.5 | 0.14 | 1.00 |

| 2 | Feeling hot | 0.99 (0.91) | 1.03 (0.93) | 78,216 | 0.53 | 1.00 |

| 3 | Wobbliness in legs | 0.72 (0.83) | 0.77 (0.84) | 76,879.5 | 0.28 | 1.00 |

| 4 | Unable to relax | 1.64 (0.94) | 1.61 (0.97) | 81,104.5 | 0.77 | 1.00 |

| 5 | Fear of worst happening | 1.46 (0.96) | 1.56 (1.00) | 75,714 | 0.16 | 1.00 |

| 6 | Dizzy or lightheaded | 1.20 (0.94) | 1.17 (0.94) | 80,992.5 | 0.80 | 1.00 |

| 7 | Heart pounding/racing | 1.47 (0.88) | 1.46 (0.96) | 81,205.5 | 0.74 | 1.00 |

| 8 | Unsteady | 1.36 (0.87) | 1.42 (0.90) | 76,784.5 | 0.27 | 1.00 |

| 9 | Terrified or afraid | 1.31 (0.96) | 1.39 (0.97) | 77,055.5 | 0.32 | 1.00 |

| 10 | Nervous | 1.75 (0.89) | 1.72 (0.94) | 81,274.5 | 0.73 | 1.00 |

| 11 | Feeling of choking | 1.05 (1.02) | 1.06 (1.02) | 79,616.5 | 0.86 | 1.00 |

| 12 | Hands trembling | 0.90 (0.95) | 1.03 (1.02) | 74,967 | 0.10 | 1.00 |

| 13 | Shaky | 1.23 (0.93) | 1.35 (0.97) | 74,409.5 | 0.07 | 1.00 |

| 14 | Fear of losing control | 1.19 (1.03) | 1.21 (1.08) | 79,573 | 0.85 | 1.00 |

| 15 | Difficulty in breathing | 0.99 (0.99) | 1.06 (1.01) | 77,491 | 0.39 | 1.00 |

| 16 | Fear of dying | 0.91 (0.92) | 0.96 (1.04) | 78,531.5 | 0.6 | 1.00 |

| 17 | Scared | 1.76 (0.89) | 1.77 (0.92) | 79,347 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

| 18 | Indigestion | 1.37 (0.96) | 1.30 (0.98) | 83,617 | 0.28 | 1.00 |

| 19 | Faint | 0.59 (0.88) | 0.61 (0.87) | 78,025.5 | 0.46 | 1.00 |

| 20 | Face flushed | 0.76 (0.88) | 0.76 (0.91) | 81,235 | 0.73 | 1.00 |

| 21 | Hot/cold sweats | 0.83(0.96) | 0.82 (0.94) | 80,569.5 | 0.90 | 1.00 |

| Total score | 24.63 (12.21) | 25.11 (12.35) | 78,388 | 0.59 | 1.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, S.S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Lee, D.; Yu, H.; Kang, H.S.; Ha, T.H.; Park, J.; Myung, W. Understanding Anxiety Symptoms of Mood Disorders Across Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder Using Network Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2245. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122245

Kwon SS, Lee H, Lee J, Jang J, Lee D, Yu H, Kang HS, Ha TH, Park J, Myung W. Understanding Anxiety Symptoms of Mood Disorders Across Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder Using Network Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2245. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122245

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Sarah Soonji, Hyukjun Lee, Jakyung Lee, Junwoo Jang, Daseul Lee, Hyeona Yu, Hyo Shin Kang, Tae Hyon Ha, Jungkyu Park, and Woojae Myung. 2025. "Understanding Anxiety Symptoms of Mood Disorders Across Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder Using Network Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2245. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122245

APA StyleKwon, S. S., Lee, H., Lee, J., Jang, J., Lee, D., Yu, H., Kang, H. S., Ha, T. H., Park, J., & Myung, W. (2025). Understanding Anxiety Symptoms of Mood Disorders Across Bipolar and Major Depressive Disorder Using Network Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2245. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122245