Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- Studies on human adult subjects (age ≥ 18 years).

- -

- Articles published in English.

- -

- Studies focusing on the diagnostic performance, clinical utility, comparative effectiveness, or integration of echocardiography, cardiac computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or nuclear imaging techniques in the diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis.

- -

- No specific diagnostic performance thresholds were required for inclusion, in keeping with the broad scope of this review.

- -

- Priority was given to clinical guidelines, randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case–control studies, large case series (>10 patients), and societal guidelines.

- -

- Studies about native valve endocarditis (NVE), prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE), and/or cardiac implantable electronic device (CIED) endocarditis were all considered eligible.

- -

- Studies conducted exclusively on pediatric populations.

- -

- Studies not published in English.

- -

- Studies not primarily focused on cardiac imaging or where the relevant imaging data could not be extracted.

- -

- Studies focusing exclusively on non-cardiac or highly specific cardiac devices (e.g., ventricular assist devices, left atrial appendage occluders, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair systems) were excluded, as the available evidence was limited and their inclusion would have made the scope of the review too broad.

3. Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis

- (1)

- Typical microorganisms consistent with IE from two separate blood cultures: Oral streptococci, Streptococcus Gallolyticus (formerly S. Bovis), HACEK group, S. aureus, E. faecalis. Specifically, the sample might be acquired through:

- two separate blood cultures (drawn 30 min apart or 12 h apart) or

- all of 3 or a majority of ≥4 separate cultures of blood (with first and last samples drawn ≥1 h apart).

- (2)

- Evidence of infective endocardial involvement demonstrated by imaging findings such as valvular, perivalvular/periprosthetic and foreign material anatomic and metabolic lesions characteristic of IE. These lesions can be detected by any of the following imaging techniques: echocardiography (TTE and TEE), cardiac CT, [18F]-FDG-PET/CT(A) and WBC SPECT/CT.

- Predisposing heart condition (such as having a prosthetic heart valve or previous heart infection) or injection drug use

- Fever above > 38 °C (100.4 °F)

- Vascular phenomena (such as major arterial emboli—blockages in large arteries, septic pulmonary infarcts—infections causing dead lung tissue, mycotic aneurysm—a blood vessel swelling caused by infection, intracranial hemorrhage—bleeding in the brain, conjunctival hemorrhages—bleeding in the eye, or Janeway lesions—painless red or purple skin spots)

- Immunological phenomena (such as glomerulonephritis—a type of kidney inflammation, Osler’s nodes—tender bumps on fingers or toes, Roth’s spots—retinal hemorrhages in the eye, or a positive rheumatoid factor—a blood antibody).

- Microbiological evidence not meeting major criteria (positive blood culture or serological evidence—blood test showing immune response—infection with an organism consistent with Infective endocarditis.

Blood Culture-Negative Endocarditis

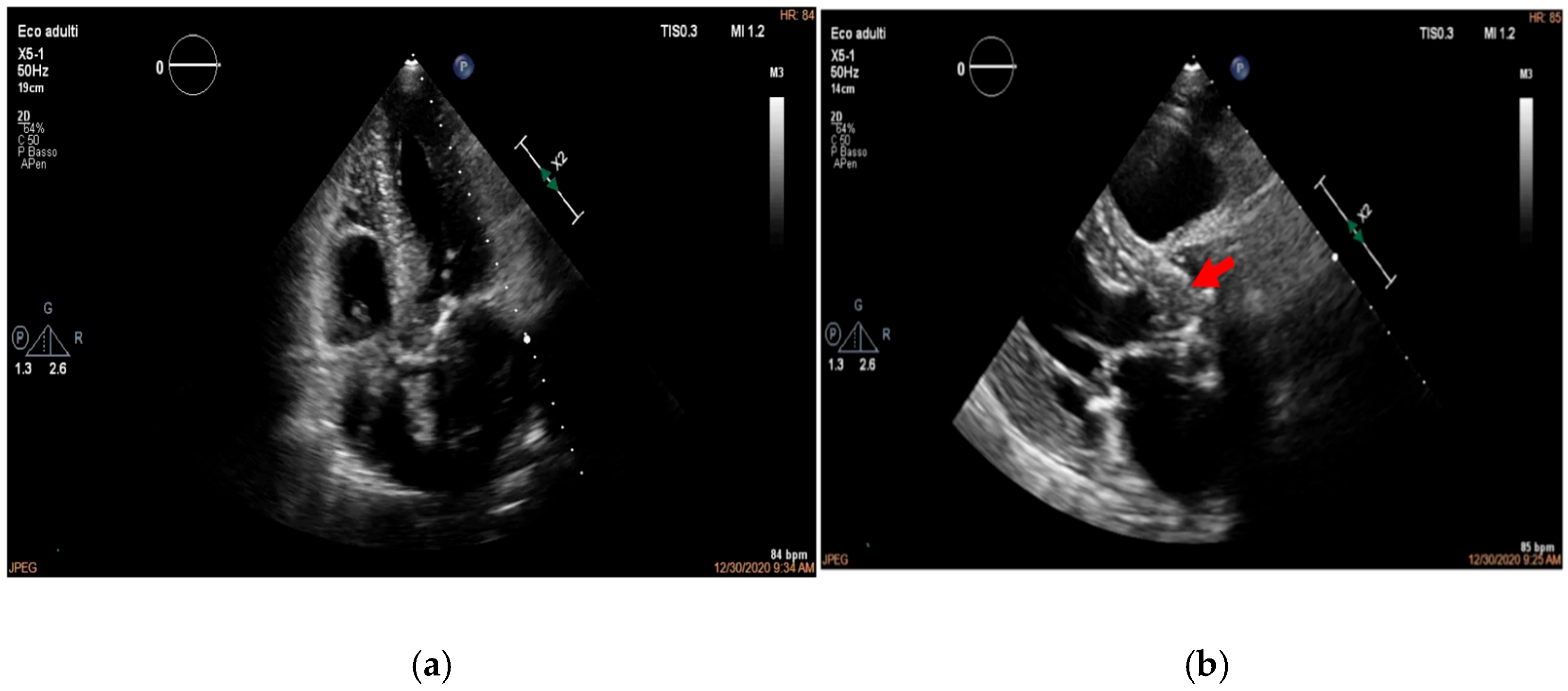

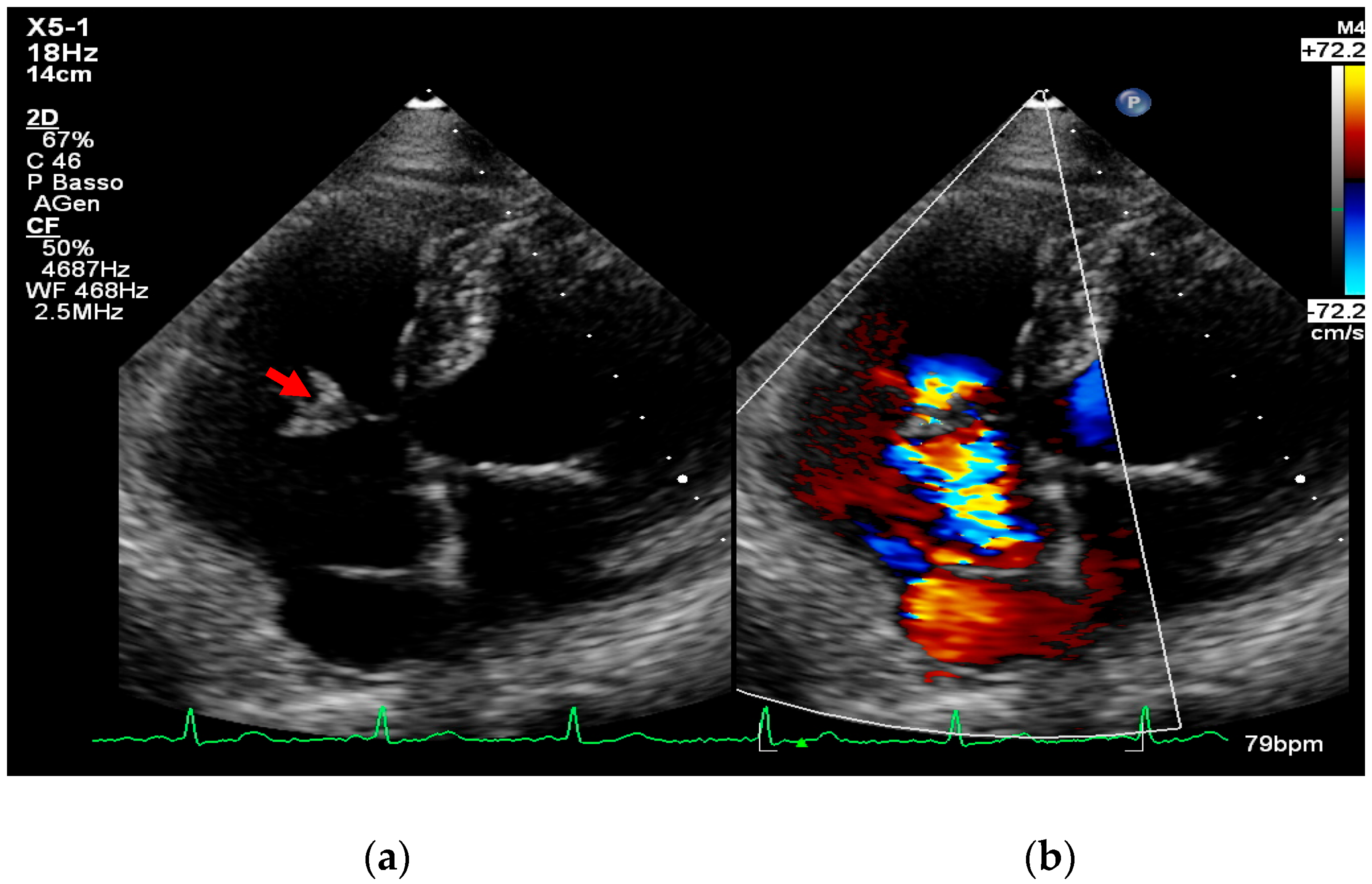

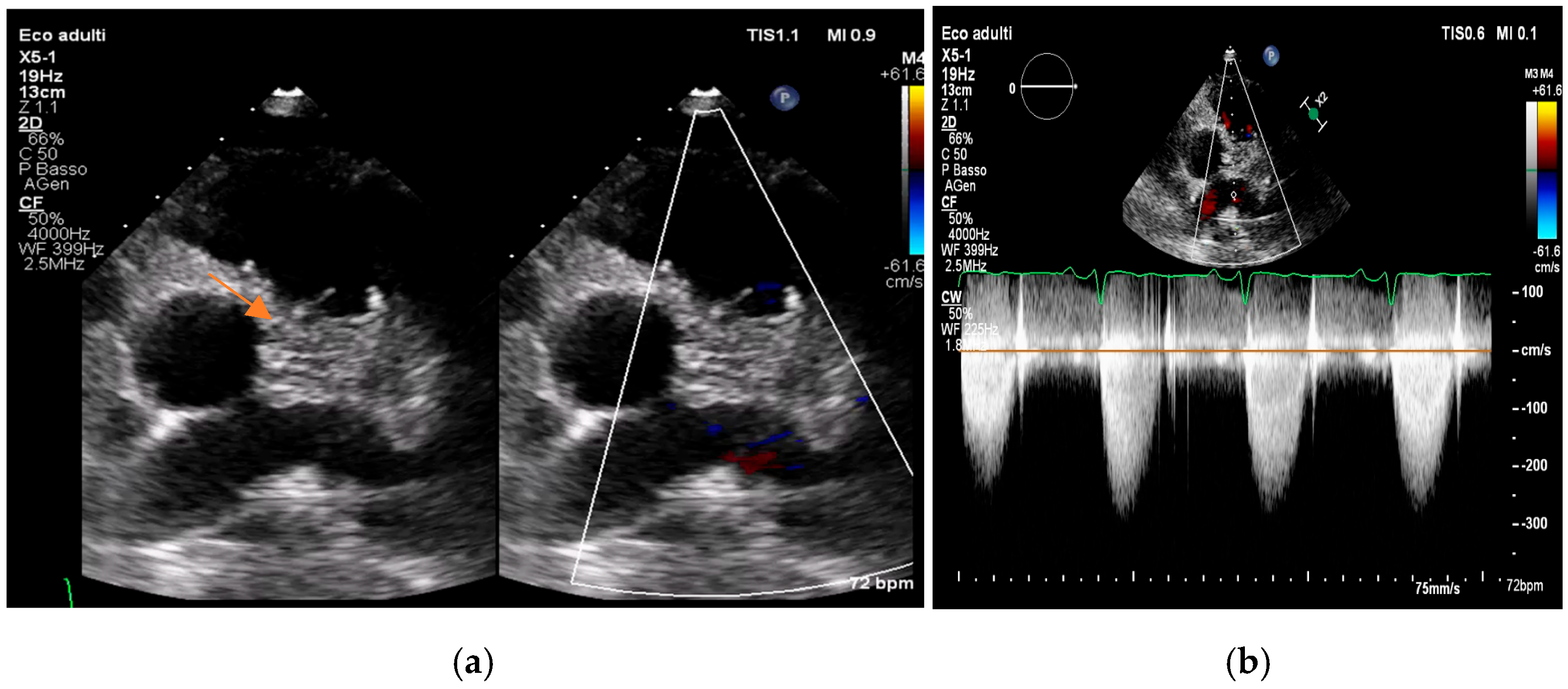

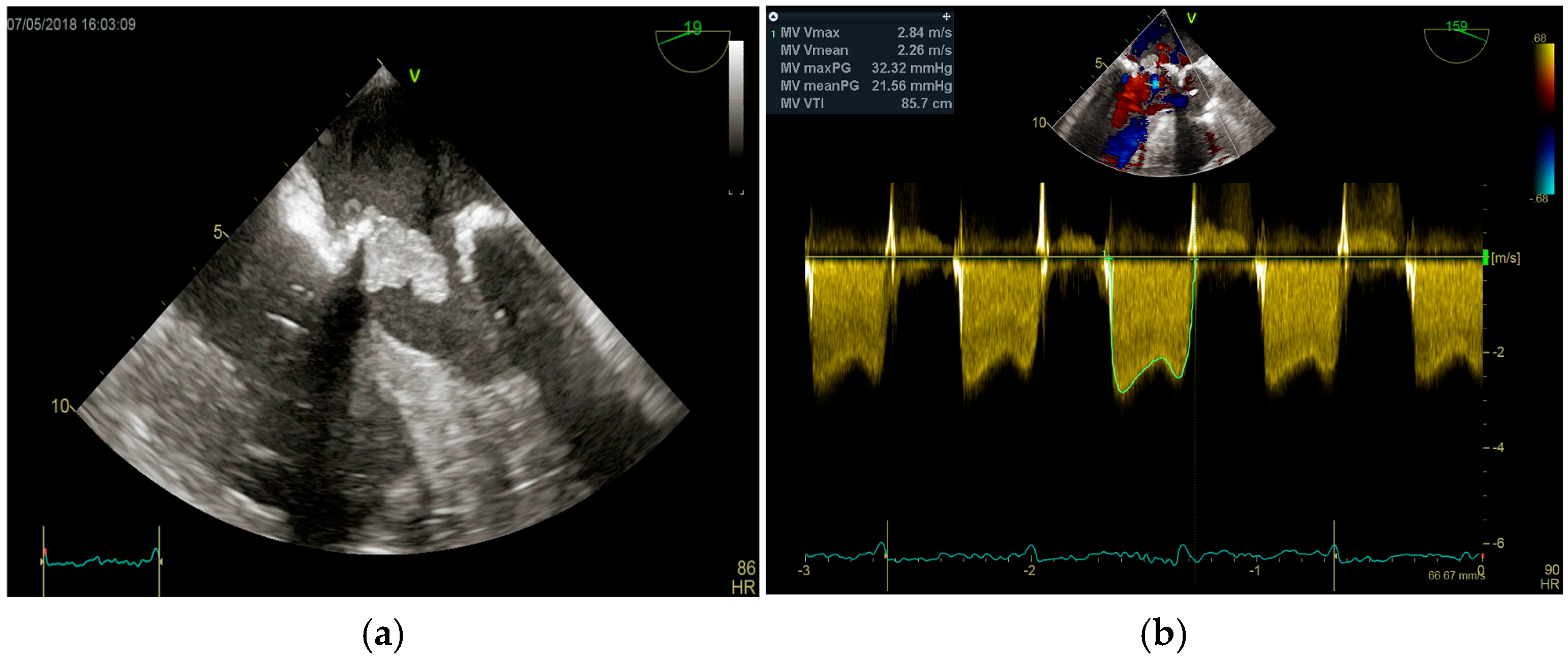

4. Echocardiography

- valvular or leaflet perforation, i.e., tissue defects causing valvular regurgitation originating from the site of perforation.

- valvular aneurysm, a saccular outpouching of a valve leaflet, protruding into the atrium or ventricle.

- perivalvular or perigraft abscess, an echolucent or echodense area adjacent to the valve annulus or prosthetic ring often with irregular borders and sometimes with evidence of cavity formation.

- pseudoaneurysm, a contrast-filled outpouching with a narrow neck communicating with the cardiac lumen, often adjacent to the valve annulus. On echocardiography, it appears as a pulsatile cavity with systolic expansion and diastolic collapse.

- intracardiac fistula, visualized as an abnormal communication between cardiac chambers or vessels, is often detected by using color Doppler.

- significant new valvular regurgitation compared with previous imaging, i.e., increase in regurgitant jet size, vena contracta width…

Differential Diagnosis

5. Cardiac Computed Tomography

6. Magnetic Resonance

6.1. The Primary Role: Detection of Embolic Complications

- -

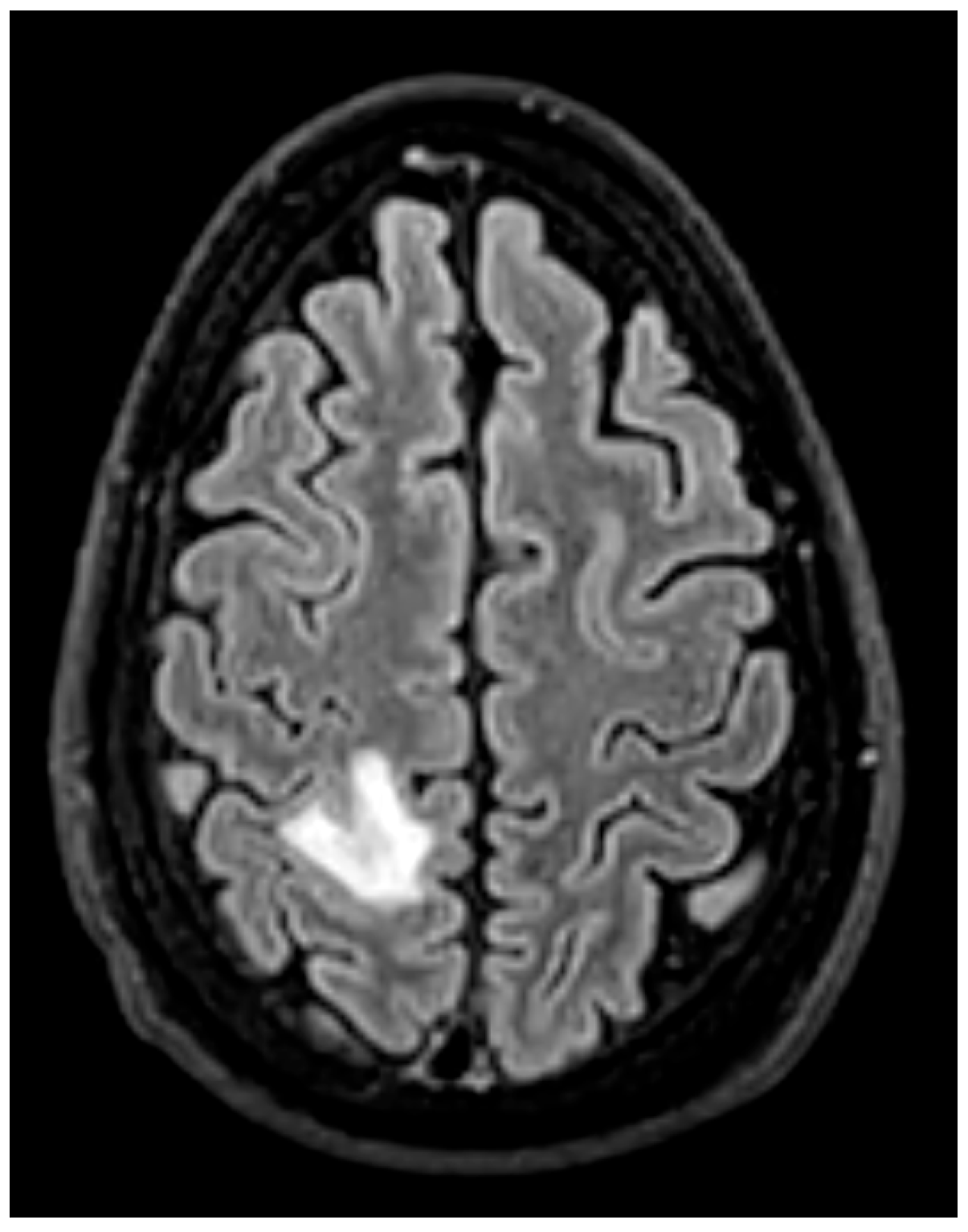

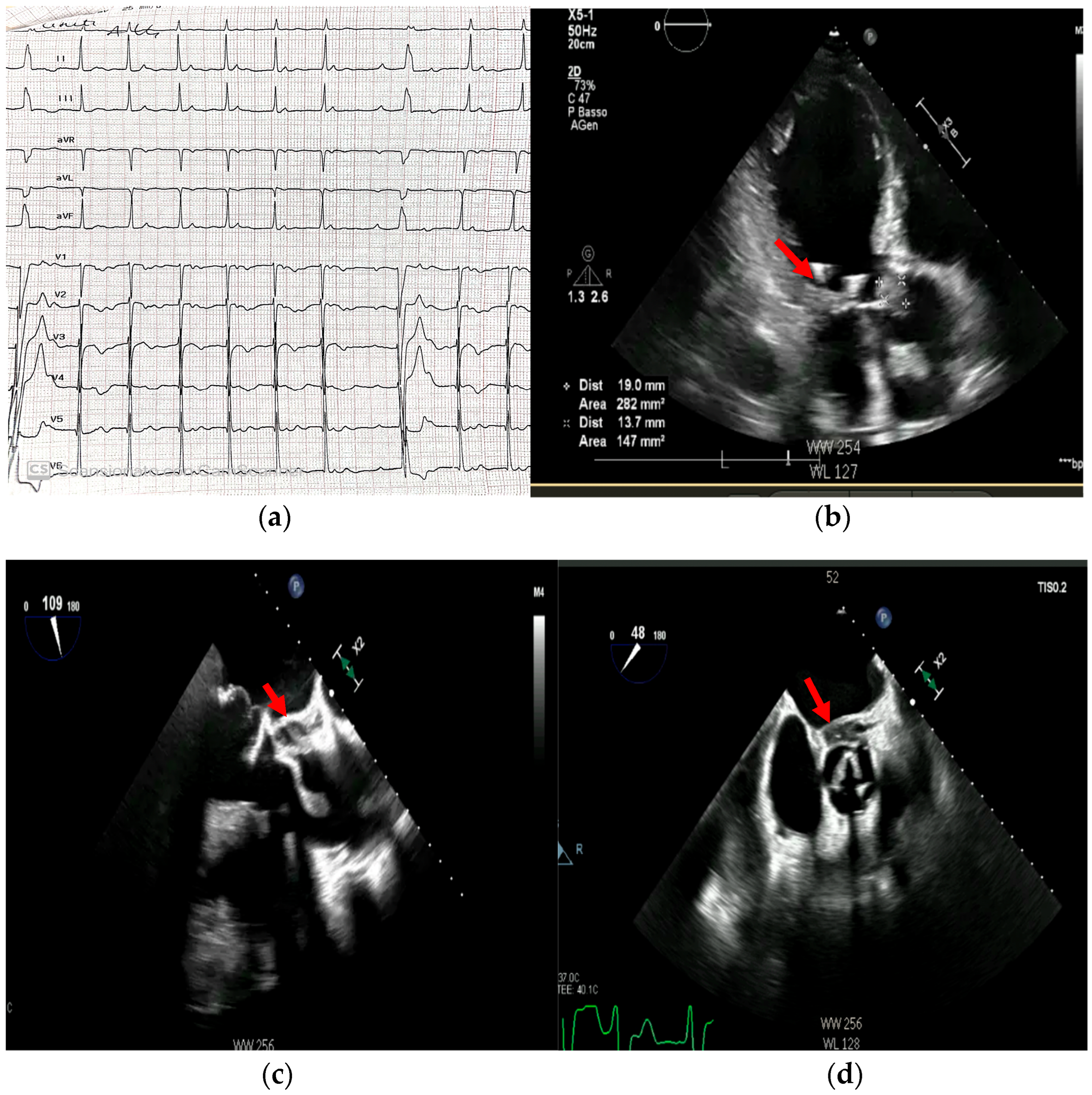

- Brain MRI is especially valuable for identifying clinically occult cerebral emboli, which can influence management decisions and prognosis [24,36] (Figure 15). These occur in 20–40% of IE cases, and a significant portion are clinically silent. Brain MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) is the most sensitive modality for detecting acute cerebral infarcts, microabscesses, mycotic aneurysms, and hemorrhages [35,38]. Identifying these findings, even in asymptomatic patients, is critical as it can significantly influence surgical timing and risk stratification. The 2023 ESC guidelines recommend considering brain MRI before cardiac surgery in patients with IE, especially in those with neurological symptoms or high-risk clinical features [13]. For example, the presence of a large cerebral infarct, hemorrhagic lesions, or mycotic aneurysms may prompt delay of valve surgery to reduce the risk of perioperative neurological complications. Conversely, detection of small, non-hemorrhagic embolic lesions may support earlier surgery to prevent further embolization [30]. Prospective data demonstrate that routine cerebral MRI led to changes in surgical plans in up to 14% of cases, including both delays and accelerations of surgery based on neurological risk [39].

- -

- Whole-Body MRI: While less established than PET/CT, whole-body MRI can be used to detect embolic phenomena in other organs, such as the spleen and kidneys, particularly in patients for whom radiation exposure is a major concern [40].

6.2. The Complementary Role in Cardiac Assessment

- Assessment of Perivalvular Complications: Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) CMR can help characterize perivalvular tissue. In cases where echocardiography and CT are inconclusive, CMR can identify perivalvular abscesses or pseudoaneurysms by demonstrating a core of hyperintense signal on T2-weighted images (edema) with peripheral LGE (inflammatory capsule) [38,41].

- Comprehensive Functional Assessment: CMR provides the reference standard for quantifying biventricular volumes, ejection fraction, and valvular regurgitation. This is particularly useful for serial monitoring of ventricular function during and after treatment, especially in cases of associated valve dysfunction or heart failure.

6.3. Contrasting the Role of MRI/CMR with CT and PET/CT

- vs. Cardiac CT: Cardiac CT is superior for detailed anatomical delineation of paravalvular structures, calcifications, and pseudoaneurysms due to its higher spatial resolution. It is the preferred modality for pre-surgical coronary angiography. CMR, however, provides superior soft-tissue characterization (differentiating edema, necrosis, and thrombus) and functional data without radiation [17,38].

- vs. FDG-PET/CT: PET/CT excels at detecting metabolic activity, making it superior for diagnosing active infection around prosthetic material and identifying occult septic emboli throughout the body. MRI does not assess metabolism but provides exquisite anatomical detail of embolic lesions (e.g., defining the exact size and hemorrhagic component of a splenic infarct) and can detect complications like cerebral microabscesses with higher sensitivity than CT [17,18].

7. Nuclear Imaging

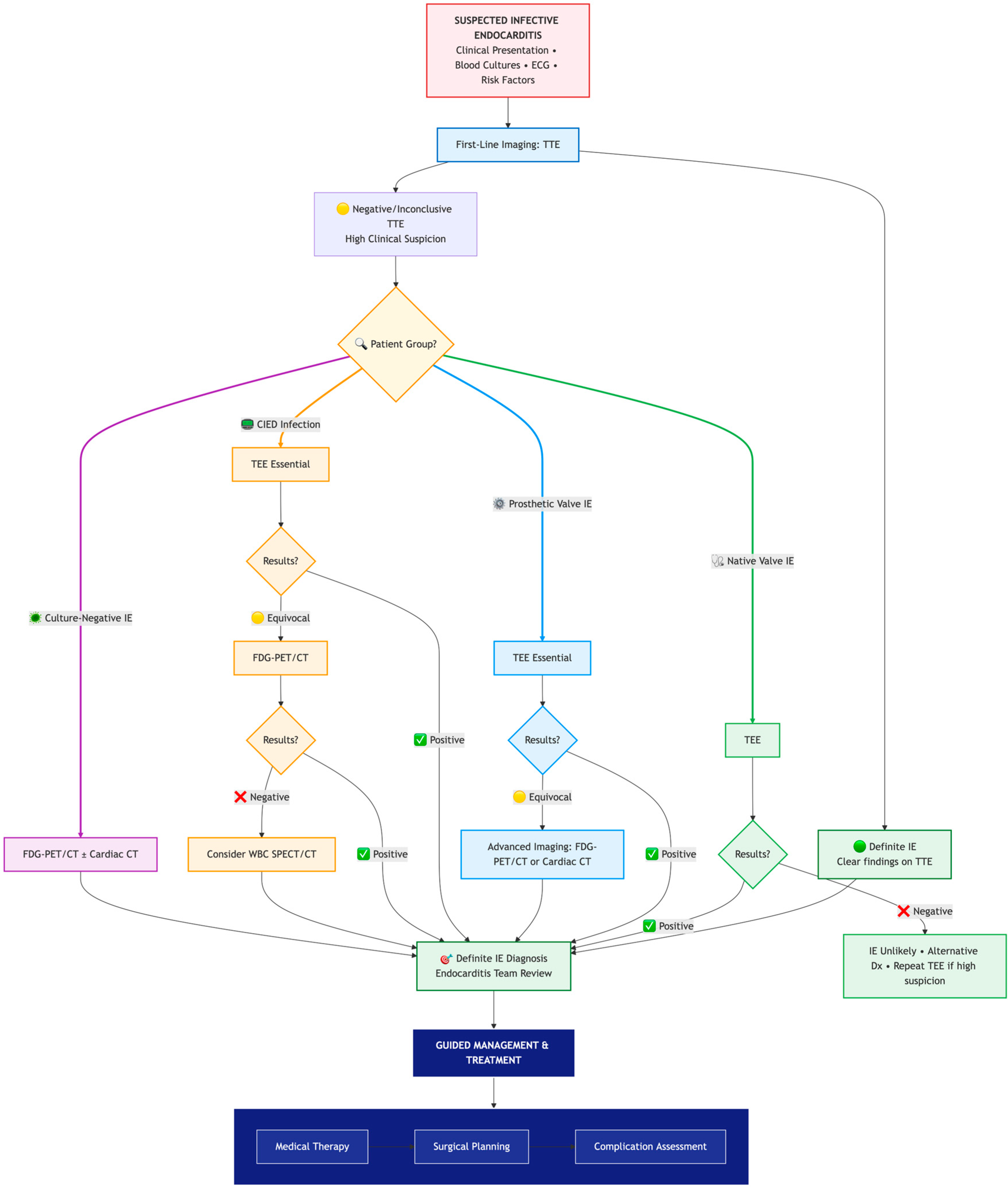

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE): FDG-PET/CT and WBC scintigraphy are recommended when echocardiography is inconclusive or negative, but clinical suspicion remains high. These modalities are especially valuable for detecting perivalvular infection, invasive complications, and extracardiac septic emboli. Abnormal focal uptake around the prosthesis is considered a significant criterion for PVE diagnosis, and can reclassify cases from “possible” to “definite” IE within the modified Duke criteria framework [13,43,44,45]

- Cardiac device infections: Nuclear imaging is indicated for suspected infection of cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) when conventional imaging is non-diagnostic. FDG-PET/CT can identify device pocket infection, lead infection, and associated extracardiac complications, and is integrated into the diagnostic algorithm for device-related IE [46]

- Reclassification from possible to definite IE: The ESC guidelines incorporate abnormal FDG-PET/CT or WBC scintigraphy findings as a significant criterion for IE diagnosis in patients with prosthetic valves or devices. This allows for reclassification of cases initially deemed “possible” IE to “definite” IE when nuclear imaging demonstrates focal uptake consistent with infection, particularly in the setting of non-diagnostic echocardiography or ambiguous clinical findings (Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18) [43,44,46].

Advanced Imaging in Cardiac Implantable Devices

8. Multimodality Imaging and Clinical Synergy: From Diagnosis to Management

8.1. Constructing the Diagnostic Puzzle

8.2. When Clinical Findings Reshape the Pathway: The Case of Systemic Embolism

8.2.1. Triggering an Expeditious and Expanded Diagnostic Workup

- -

- Confirmation of IE: In a patient with suspected IE but an inconclusive initial echocardiography, a new embolic event significantly raises the pre-test probability. This should prompt an urgent repeat transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and strongly warrant the use of advanced imaging to secure the diagnosis

- -

- Search for Silent Emboli: A single clinically apparent embolus is often the “tip of the iceberg.” The discovery of one embolic event mandates a systematic search for other, silent emboli, particularly cerebral, which can drastically alter surgical risk and timing. As such, whole-body CT angiography or FDG-PET/CT is recommended to define the full embolic burden [13,39]. Brain MRI is the gold standard for detecting silent cerebral emboli and should be strongly considered before surgery in high-risk patients, even in the absence of neurological symptoms [22].

8.2.2. Directly Influencing Surgical Indications and Timing

- -

- Recurrent Emboli: The occurrence of a second, clinically recognizable embolic event during appropriate antibiotic therapy is a strong indication for urgent surgery to remove the embolic source, irrespective of vegetation size or antibiotic course duration.

- -

- Large Vegetation Size: While controversial, a persistent large vegetation (>10 mm) following a single embolic event is a Class IIa recommendation for surgery, reflecting the desire to pre-empt a potentially catastrophic recurrence [13].

- -

- Impact of Silent Emboli: The discovery of multiple silent emboli, particularly cerebral, creates a complex risk-benefit calculus. While not a direct surgical indication, it necessitates a nuanced, multidisciplinary decision regarding the timing of surgery to balance the risk of recurrent embolism against the risk of hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarcts.

9. Multidisciplinary Approach

10. Limitations, Evidence Gaps, and Future Research

10.1. Pitfalls and Limitations of Advanced Imaging

- -

- Echocardiography: As the cornerstone of diagnosis, echocardiography’s limitations in the setting of prosthetic material and operator dependence are well-known. The presence of sewing ring and stent frame shadowing can obscure critical findings, and Doppler flow malalignment may lead to underestimation of prosthetic valve gradients and regurgitation severity [37,58].

- -

- FDG-PET/CT: Sterile post-surgical inflammation can cause increased FDG uptake, leading to false positives and reduced specificity within the first 1–3 months after valve implantation or cardiac surgery. Therefore, caution is advised when interpreting FDG-PET/CT results during this period [18,59]. Moreover, strict patient preparation is required in order to suppress physiological myocardial glucose uptake and improve diagnostic accuracy. A minimum 6 h fast and a low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet prior to imaging is needed, as this reduces background myocardial FDG uptake and enhances visualization of infectious foci. This stringent preparation can be challenging to achieve in acutely ill or diabetic patients, potentially limiting its real-world applicability.

- -

- Cardiac CT: While excellent for anatomical definition, cardiac CT has limited sensitivity for small (<10 mm) mobile vegetations and cannot assess hemodynamic status. Its use is also limited by radiation exposure and the need for a stable sinus rhythm for accurate electrocardiographic gating, as arrhythmias can degrade image resolution and diagnostic yield [37,60,61]. Additionally, the use of iodinated contrast media carries a risk of nephrotoxicity, a relevant concern in a patient population often affected by chronic kidney disease.

10.2. Ongoing Controversies

- -

- Standardized Protocols: Future research must focus on standardizing imaging protocols (e.g., patient preparation for FDG-PET/CT, standardized scoring systems, and Standardized Uptake Value measurements, describing pattern and distribution of uptake…) and reporting criteria to improve consistency and comparability across studies. Crucially, large, prospective, multicenter studies are needed to validate whether these advanced imaging strategies, when guided by a multidisciplinary team, translate into a measurable improvement in hard outcomes such as mortality, recurrent embolization, and need for reoperation.

10.3. Emerging Technologies

- -

- Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models have demonstrated promise in improving diagnostic accuracy for prosthetic valve endocarditis, with automated vegetation quantification enhancing risk stratification. Machine learning algorithms can predict postsurgical mortality and identify high-risk patients using imaging and biomarker data. Recent literature highlights that AI/ML can outperform traditional diagnostic methods in certain contexts, especially in complex cases such as prosthetic valve or device-related IE [62]. Current consensus supports the use of AI-enhanced imaging as a supplement to, not a replacement for, expert clinical judgment and multidisciplinary team-based decision-making in IE [17,21,55]. These technologies offer potential for real-time decision support and personalized management, but require rigorous external validation and assessment of clinical workflow integration before routine adoption [62].

- -

- Novel radiotracers, such as 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT/CT (Technetium-99m-Hexamethylpropyleneamine Oxime) and experimental PET agents, have demonstrated improved specificity for infection over inflammation in small cohorts, but their clinical utility and cost-effectiveness remain unproven in large, multicenter studies [63,64]. 99mTc-HMPAO-SPECT/CT provides additional specificity by directly imaging leukocyte accumulation at sites of active infection [51,64]. Emerging PET tracers target bacterial components or specific leukocyte subsets [65]. Hybrid molecular imaging, such as PET/MRI, is also being explored for simultaneous molecular and anatomical assessment, with potential advantages in soft tissue characterization and reduced radiation exposure [18].

10.4. Key Unanswered Questions Include

- -

- What is the optimal timing and modality for follow-up imaging after initiation of treatment or device extraction?

- -

- How can healthcare systems address the significant access disparities and cost barriers associated with advanced imaging modalities like FDG-PET/CT?

- -

- And ultimately, do these advanced imaging strategies, when guided by a multidisciplinary team, translate into a measurable improvement in hard outcomes such as mortality and recurrent embolization? Most of the current data derives from observational studies, rather than randomized trials.

11. Summary and Recommendations

11.1. Practical Recommendations for Clinical Practice

- Always start with TTE, followed by TEE in suspected cases and specific populations (e.g, prosthetic heart valves).

- Use cardiac CT for suspected paravalvular complications or when TEE is non-diagnostic.

11.2. Key Points

- Diagnostic Hierarchy is Critical: While transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is the essential first-line test, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is often mandatory, and its limitations in the setting of prosthetic material must be actively recognized.

- Scenario-Based Imaging Selection is Paramount: The diagnostic pathway must be tailored, with early integration of advanced modalities like FDG-PET/CT and Cardiac CT for prosthetic valve and cardiac device-related infections, where they significantly increase diagnostic certainty.

- Advanced Modalities Offer Complementary Data: Cardiac CT excels at defining paravalvular anatomy for surgery, FDG-PET/CT detects occult metabolic activity and emboli, and MRI is indispensable for diagnosing silent cerebral complications.

- Clinical Vigilance Drives Management Shifts: The occurrence of systemic embolism is not just a diagnostic clue but a pivotal event that should trigger an escalated imaging protocol and urgent surgical evaluation.

- A Multidisciplinary Endocarditis Team is Non-Negotiable: Optimal patient outcomes depend on the collaborative interpretation of multimodality imaging findings within a dedicated team framework to guide complex therapeutic decisions.

- Acknowledge the Evidence Landscape: Practitioners must be aware of modality-specific pitfalls (e.g., PET/CT’s post-surgical inflammation, MRI’s limited spatial resolution) and that many recommendations are grounded in expert consensus, requiring integration with clinical judgment.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IE | Infective Endocarditis |

| CIED | Cardiac implantable Electronic Devices |

| ESC | European society of cardiology |

| PET/CT | Positron Emission Tomography/Computerized Scan |

| AHA | American Heart Association |

| ACC | American College of Cardiology |

| TEE | Transesophageal Echocardiography |

| TTE | Transthoracic Echocardiography |

| ISCVID | International Society for CardioVascular Infectious Diseases |

| SPECT | Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography |

| AV | Atrioventricular |

| PVE | Prosthetic Valve Endocarditis |

| NVE | Native Valve Endocarditis |

| WBC | White Blood Cells |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| 99mTc | Technetium-99m |

| HMPAO | Hexamethylpropyleneamine Oxime) |

| MAIVF | Mitral-Aortic Intervalvular Fibrosa |

| LCA | Left Coronary Artery |

| BVP | Biological Valve Prosthesis |

| LVOT | Left Ventricular Outflow Tract |

| LA | Left Atrium |

| DWI | Diffusion-Weighted Imaging |

| MALDI | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization |

| TOF | Time-of-Flight |

| NBTE | Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis |

| BCNE | Blood Culture Negative Endocarditis |

References

- Murdoch, D.R. Clinical Presentation, Etiology, and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis in the 21st Century: The International Collaboration on Endocarditis–Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosioni, J.; Hernández-Meneses, M.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Tattevin, P.; Olaison, L.; Freiberger, T. Epidemiological Changes and Improvement in Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis in Europe in the Twenty-First Century: An International Collaboration on Endocarditis (ICE) Prospective Cohort Study (2000–2012). Infect. Dis. Ther. 2023, 12, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, D.H.; Woolhandler, S.; Nardin, R.; Brusch, J.; Himmelstein, D.U. Infective Endocarditis in the U.S., 1998–2009: A Nationwide Study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, H.F.; Bayer, A.S. Native-Valve Infective Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylonakis, E.; Calderwood, S.B. Infective Endocarditis in Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1318–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.S.V.; McAllister, D.A.; Gallacher, P.; Astengo, F.; Rodríguez Pérez, J.A.; Hall, J. Incidence, Microbiology, and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized with Infective Endocarditis. Circulation 2020, 141, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talha, K.M.; DeSimone, D.C.; Sohail, M.R.; Baddour, L.M. Pathogen influence on epidemiology, diagnostic evaluation and management of infective endocarditis. Heart 2020, 106, 1878–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Gaca, J.G.; Chu, V.H. Management Considerations in Infective Endocarditis: A Review. JAMA 2018, 320, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selton-Suty, C.; Célard, M.; Le Moing, V.; Doco-Lecompte, T.; Chirouze, C.; Iung, B. Preeminence of Staphylococcus aureus in Infective Endocarditis: A 1-Year Population-Based Survey. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slipczuk, L.; Codolosa, J.N.; Davila, C.D.; Romero-Corral, A.; Yun, J.; Pressman, G.S. Infective Endocarditis Epidemiology Over Five Decades: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, S.J.; Mediratta, A.; Gillam, L.D. Cardiovascular Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Multimodality Approach. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, e008956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, S.; Arvanitaki, A.; Oldfield, K.; Tsoumani, Z.; Iannaccone, G.; Kacar, P.; Dahiya, A.; Montanaro, C. A multimodality imaging approach to the diagnosis of infective endocarditis: Incremental value of combining modalities. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 41, 1907–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; De Waha, S.; Bonaros, N.; Brida, M.; Burri, H. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3948–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowler, V.G.; Durack, D.T.; Selton-Suty, C.; Athan, E.; Bayer, A.S.; Chamis, A.L.; Dahl, A.; DiBernardo, L.; Durante-Mangoni, E.; Duval, X.; et al. The 2023 Duke-International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Criteria for Infective Endocarditis: Updating the Modified Duke Criteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Vaart, T.W.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; Durack, D.T.; Baddour, L.M.; Bayer, A.S.; Durante-Mangoni, E. External Validation of the 2023 Duke–International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases Diagnostic Criteria for Infective Endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 78, 922–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boufoula, I.; Philip, M.; Arregle, F.; Tessonnier, L.; Camilleri, S.; Hubert, S. Comparison between Duke, European Society of Cardiology 2015, International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases 2023, and European Society of Cardiology 2023 criteria for the diagnosis of transcatheter aortic valve replacement-related infective endocarditis. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2025, 26, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broncano, J.; Rajiah, P.S.; Vargas, D.; Sánchez-Alegre, M.L.; Ocazionez-Trujillo, D.; Bhalla, S. ultimodality Imaging of Infective Endocarditis. RadioGraphics 2024, 44, e230031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.; Glaudemans, A.W.J.M.; Touw, D.J.; Van Melle, J.P.; Willems, T.P.; Maass, A.H. Diagnostic value of imaging in infective endocarditis: A systematic review. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, M.; Tessonier, L.; Mancini, J.; Mainardi, J.-L.; Fernandez-Gerlinger, M.-P.; Lussato, D. omparison Between ESC and Duke Criteria for the Diagnosis of Prosthetic Valve Infective Endocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 13, 2605–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSimone, D.C.; Garrigos, Z.E.; Marx, G.E.; Tattevin, P.; Hasse, B.; McCormick, D.W. Blood Culture–Negative Endocarditis: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association: Endorsed by the International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases. J. Am. Hear. Assoc. 2025, 14, e040218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, A.; Wiefels, C.; Lau, L.; Cuellar-Calabria, H.; Palomar Muñoz, A.; Diez, M.J.; Herance, J.R.; Erba, P.A.; Pizzi, M.N. Contemporary Approaches to the Use of Imaging in Infective Endocarditis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2025. Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, A.D.; Steinberg, M.; Showler, A.; Burry, L.; Bhatia, R.S.; Tomlinson, G.A. Diagnostic Accuracy of Transthoracic Echocardiography for Infective Endocarditis Findings Using Transesophageal Echocardiography as the Reference Standard: A Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 639–646.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, C.A.; Zaccaria, S.; Casali, G.; Nicolardi, S.; Albanese, M. Echocardiography in Endocarditis. Echocardiography 2024, 41, e15945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddour, L.M.; Wilson, W.R.; Bayer, A.S.; Fowler, V.G.; Tleyjeh, I.M.; Rybak, M.J. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015, 132, 1435–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, T.L.; Mottram, P.M.; Stuart, R.L.; Cameron, J.D.; Moir, S. Transthoracic Echocardiography Is Still Useful in the Initial Evaluation of Patients with Suspected Infective Endocarditis: Evaluation of a Large Cohort at a Tertiary Referral Center. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P.; Gentile, F. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, e25–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoen, B.; Duval, X. Infective Endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandau, K.E.; Funk, M.; Auerbach, A.; Barsness, G.W.; Blum, K.; Cvach, M. pdate to Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, E273–E344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddour, L.M.; Esquer Garrigos, Z.; Rizwan Sohail, M.; Havers-Borgersen, E.; Krahn, A.D.; Chu, V.H. pdate on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Infections and Their Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2024, 149, e201–e216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Kim, J.B.; Sastry, B.K.S.; Chen, M. Infective endocarditis. Lancet 2024, 404, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poterała, M.; Kutarski, A.; Brzozowski, W.; Tomaszewski, M.; Gromadziński, L.; Tomaszewski, A. Echocardiographic assessment of residuals after transvenous intracardiac lead extraction. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 36, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narducci, M.L.; Di Monaco, A.; Pelargonio, G.; Leoncini, E.; Boccia, S.; Mollo, R. Presence of ‘ghosts’ and mortality after transvenous lead extraction. Europace 2016, 19, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Le Dolley, Y.; Thuny, F.; Mancini, J.; Casalta, J.-P.; Riberi, A.; Gouriet, F. Diagnosis of Cardiac Device–Related Infective Endocarditis After Device Removal. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2010, 3, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, L.; Han, Q.; Yin, X.; Feng, Y. Ghost in the right atrium: A case report on successful identification of residual fibrous tissue. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dilsizian, V.; Budde, R.P.J.; Chen, W.; Mankad, S.V.; Lindner, J.R.; Nieman, K. Best Practices for Imaging Cardiac Device–Related Infections and Endocarditis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 15, 891–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.; Rubinshtein, R.; Keynan, Y. Alternative Cardiac Imaging Modalities to Echocardiography for the Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 1410–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budde, R.P.J.; Faure, M.E.; Abbara, S.; Alkadhi, H.; Cremer, P.C.; Feuchtner, G.M. Cardiac Computed Tomography for Prosthetic Heart Valve Assessment. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2025, 86, 1203–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorska, K.; Michalowska, I.; Duchnowski, P.; Szymanski, P.; Kusmierczyk, M.; Hryniewiecki, T. The Usefulness of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in the Diagnosis of Infectious Endocarditis. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2015, 24, 767–775. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duval, X.; Iung, B.; Klein, I.; Brochet, E.; Thabut, G.; Arnoult, F. Effect of Early Cerebral Magnetic Resonance Imaging on Clinical Decisions in Infective Endocarditis: A Prospective Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2010, 152, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iung, B.; Klein, I.; Mourvillier, B.; Olivot, J.-M.; Detaint, D.; Longuet, P. Respective effects of early cerebral and abdominal magnetic resonance imaging on clinical decisions in infective endocarditis. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2012, 13, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.B.; Hsu, J.Y.; Hurwitz Koweek, L.M.; Ghoshhajra, B.B.; Beache, G.M.; Brown, R.K.J. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Infective Endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2021, 18, S52–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, H.; Restrepo, C.S.; Marmol-Velez, J.A.; Vargas, D.; Ocazionez, D.; Martinez-Jimenez, S.; Reddick, R.L.; Baxi, A.J. Infectious Diseases of the Heart: Pathophysiology, Clinical and Imaging Overview. Radiographics 2016, 36, 963–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, X.; Le Moing, V.; Tubiana, S.; Esposito-Farèse, M.; Ilic-Habensus, E.; Leclercq, F. Impact of Systematic Whole-body 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT on the Management of Patients Suspected of Infective Endocarditis: The Prospective Multicenter TEPvENDO Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, C.-I.; Munteanu, A.-E.; Mititelu, M.R.; Alexandru Ștefan, M.; Buzilă, C.-A.; Streinu-Cercel, A. Diagnostic Utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in Infective Endocarditis. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primus, C.P.; Clay, T.A.; McCue, M.S.; Wong, K.; Uppal, R.; Ambekar, S. 18F-FDG PET/CT improves diagnostic certainty in native and prosthetic valve Infective Endocarditis over the modified Duke Criteria. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 2119–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikail, N.; Hyafil, F. Nuclear Imaging in Infective Endocarditis. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Dilsizian, V. Molecular Imaging of Cardiovascular Device Infection: Targeting the Bacteria or the Host–Pathogen Immune Response? J. Nucl. Med. 2020, 61, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calais, J.; Touati, A.; Grall, N.; Laouénan, C.; Benali, K.; Mahida, B. Diagnostic Impact of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography and White Blood Cell SPECT/Computed Tomography in Patients with Suspected Cardiac Implantable Electronic Device Chronic Infection. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, e007188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, A.; Olmos, C.; Vilacosta, I.; Ortega-Candil, A.; Rodríguez-Rey, C.; Pérez-Castejón, M.J. Accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with the suspicion of cardiac implantable electronic device infections. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcman, K.; Małecka, B.; Rubiś, P.; Ząbek, A.; Szot, W.; Boczar, K. The role of 99mTc-HMPAO-labelled white blood cell scintigraphy in the diagnosis of cardiac device-related infective endocarditis. Eur. Heart J.—Cardiovasc. Imaging 2020, 21, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, J.M.; Birgersdotter-Green, U.; Bravo, P.E.; Budde, R.P.J.; Chen, W.; Chu, V.H. 18F-FDG PET/CT and radiolabeled leukocyte SPECT/CT imaging for the evaluation of cardiovascular infection in the multimodality context. Heart Rhythm 2024, 21, e1–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petkovic, A.; Menkovic, N.; Petrovic, O.; Bilbija, I.; Radovanovic, N.N.; Stanisavljevic, D. The Role of Echocardiography and Cardiac Computed Tomography in Diagnosis of Infective Endocarditis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San, S.; Ravis, E.; Tessonier, L.; Philip, M.; Cammilleri, S.; Lavagna, F. Prognostic Value of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in Infective Endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, L.; Baddour, L.; Fernández Hidalgo, N.; Brothers, T.D.; Kong, W.K.F.; Borger, M.A. Infective endocarditis: It takes a team. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 2275–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erba, P.A.; Pizzi, M.N.; Roque, A.; Salaun, E.; Lancellotti, P.; Tornos, P. Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: An Imaging Team within the Endocarditis Team. Circulation 2019, 140, 1753–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, P.; Boni, R.; Slart, R.H.; Erba, P.A. Imaging of Endocarditis and Cardiac Device-Related Infections: An Update. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2023, 53, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayer, M.J.; Quintero-Martinez, J.A.; Thornhill, M.H.; Chambers, J.B.; Pettersson, G.B.; Baddour, L.M. Recent Insights Into Native Valve Infective Endocarditis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1431–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoghbi, W.A.; Asch, F.M.; Bruce, C.; Gillam, L.D.; Grayburn, P.A.; Hahn, R.T. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Valvular Regurgitation After Percutaneous Valve Repair or Replacement. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2019, 32, 431–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swart, L.E.; Gomes, A.; Scholtens, A.M.; Sinha, B.; Tanis, W.; Lam, M.G.E.H. Improving the Diagnostic Performance of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography in Prosthetic Heart Valve Endocarditis. Circulation 2018, 138, 1412–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-C.; Chang, S.; Hong, G.-R.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, S.; Ha, J.-W. Comparison of Cardiac Computed Tomography with Transesophageal Echocardiography for Identifying Vegetation and Intracardiac Complications in Patients with Infective Endocarditis in the Era of 3-Dimensional Images. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, e006986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, O.K.; Veillet-Chowdhury, M.; Choi, A.D.; Feuchtner, G.; Lopez-Mattei, J. Cardiac computed tomography in the contemporary evaluation of infective endocarditis. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2021, 15, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MOdat, R.; Marsool Marsool, M.D.; Nguyen, D.; Idrees, M.; Hussein, A.M.; Ghabally, M. Presurgery and postsurgery: Advancements in artificial intelligence and machine learning models for enhancing patient management in infective endocarditis. Int. J. Surg. 2024, 110, 7202–7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burban, A.; Słupik, D.; Reda, A.; Szczerba, E.; Grabowski, M.; Kołodzińska, A. Novel Diagnostic Methods for Infective Endocarditis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holcman, K.; Rubiś, P.; Ząbek, A.; Boczar, K.; Podolec, P.; Kostkiewicz, M. Advances in Molecular Imaging in Infective Endocarditis. Vaccines 2023, 11, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roll, W.; Faust, A.; Hermann, S.; Schäfers, M. Infection Imaging: Focus on New Tracers? J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 59S–67S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Modality | Primary Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transthoracic Echocardiography (TTE) |

|

|

|

| Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE) |

|

|

|

| Cardiac Computed Tomography (CT) |

|

|

|

| FDG-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) |

|

|

|

| White Blood Cell SPECT/CT (WBC Scan) |

|

|

|

| Cardiac Magnetic Resonance (CMR) |

|

|

|

| Brain/Whole-Body MRI |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brugiatelli, L.; Patani, F.; Lofiego, C.; Benedetti, M.; Capodaglio, I.; Giulia, P.; Matteo, F.; Enrico, P.; Marco, N.; Maurizi, K.; et al. Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122241

Brugiatelli L, Patani F, Lofiego C, Benedetti M, Capodaglio I, Giulia P, Matteo F, Enrico P, Marco N, Maurizi K, et al. Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122241

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrugiatelli, Leonardo, Francesca Patani, Carla Lofiego, Martina Benedetti, Irene Capodaglio, Pongetti Giulia, Francioni Matteo, Paolini Enrico, Nazziconi Marco, Kevin Maurizi, and et al. 2025. "Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122241

APA StyleBrugiatelli, L., Patani, F., Lofiego, C., Benedetti, M., Capodaglio, I., Giulia, P., Matteo, F., Enrico, P., Marco, N., Maurizi, K., Giulia, F., Arianna, M., Simone, L., Benedetta, A., Chiara, G., Nicolò, S., Marco, F., Giovanni, T., Antonio, D. R., ... Vagnarelli, F. (2025). Multimodality Imaging in Infective Endocarditis: A Clinical Approach to Diagnosis. Medicina, 61(12), 2241. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122241