Temperature, Humidity and Regional Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease in Argentina

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

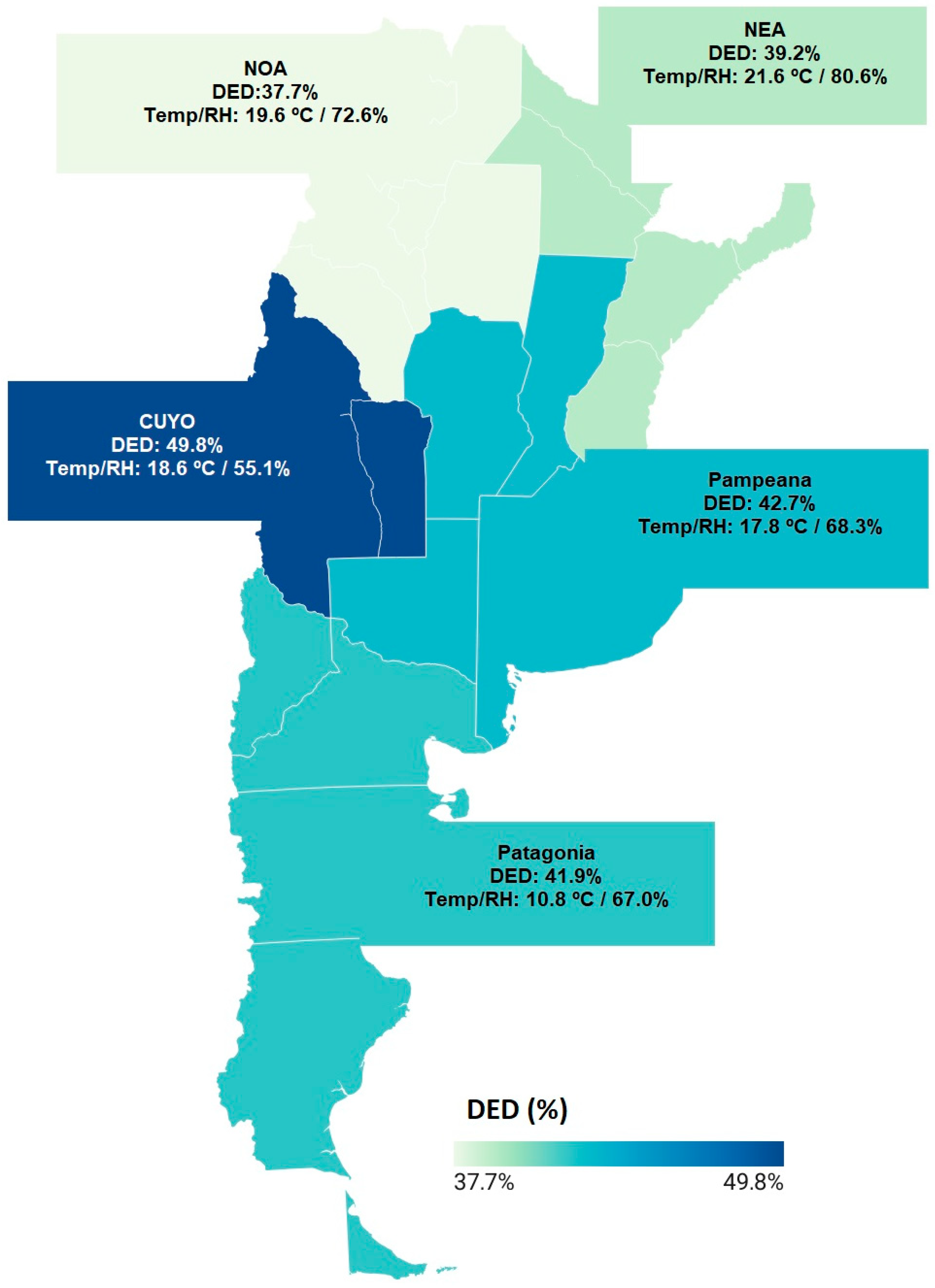

3.1. Regional Prevalence of DED and Demographic Characteristics by Region

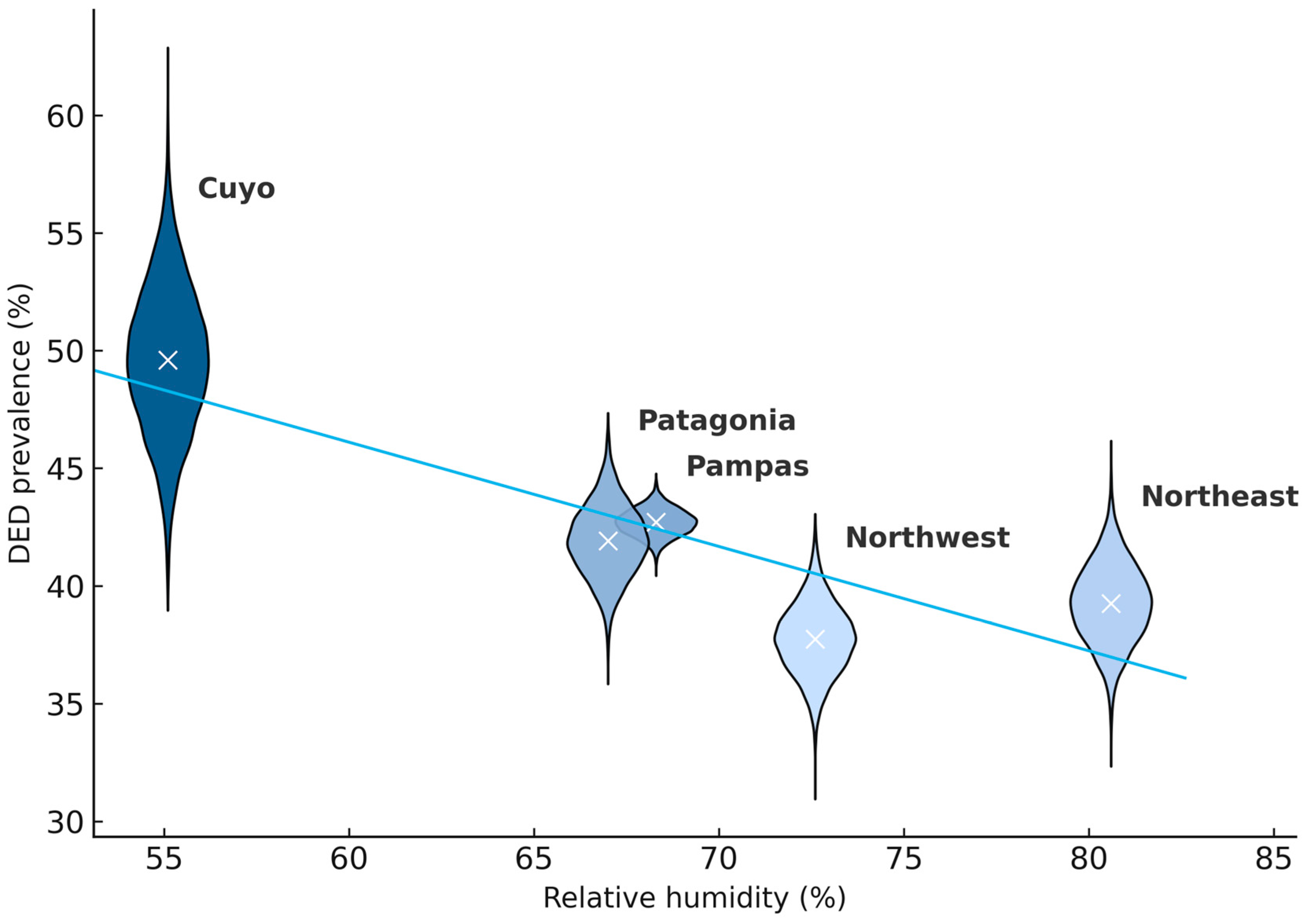

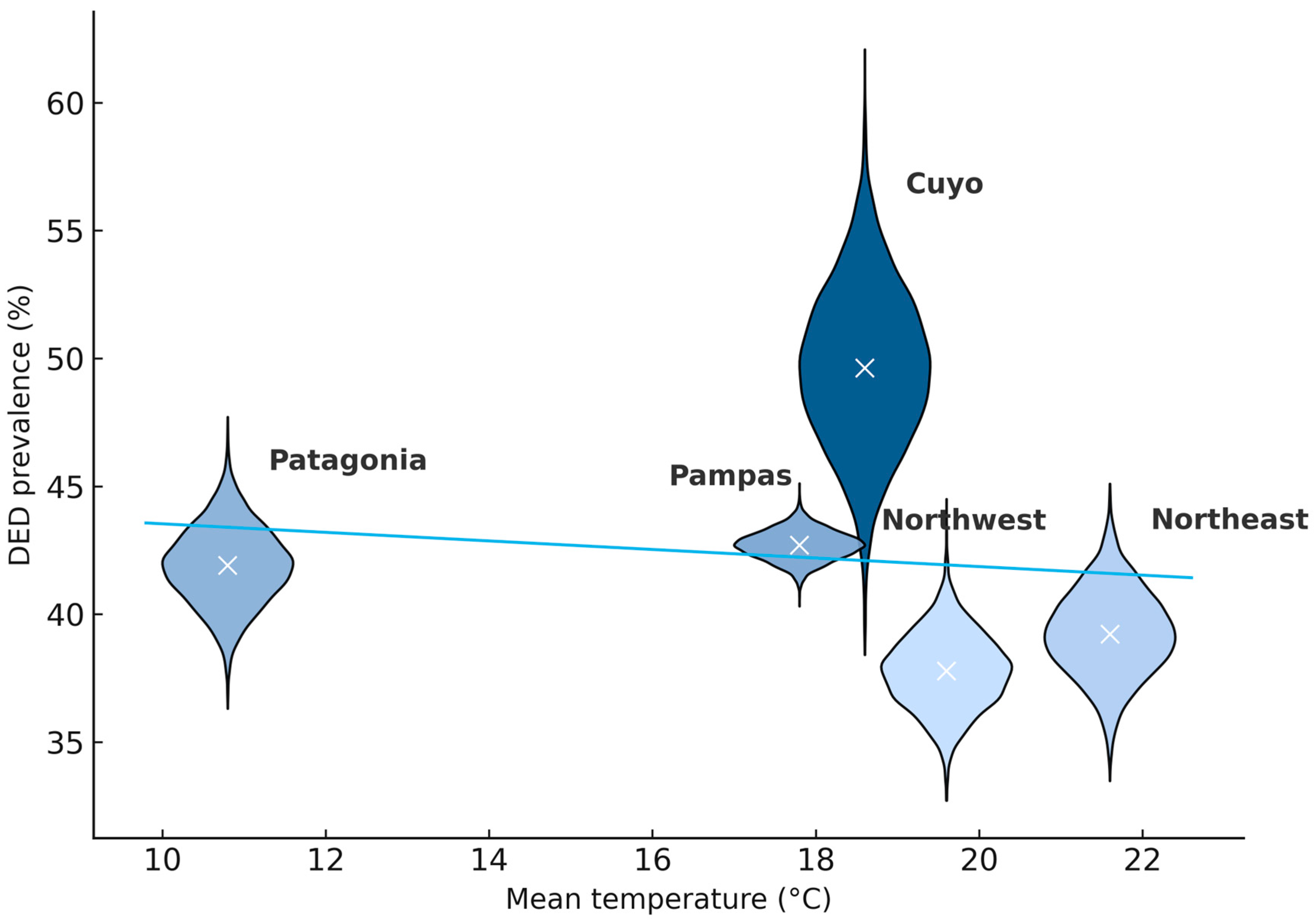

3.2. DED Prevalence, Climate Patterns, and Geographic Distribution

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DED | Dry Eye Disease |

| CAO | Consejo Argentino de Oftalmología |

| NEA | Northeast Argentina |

| NOA | Northest Argentina |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| WHS | Women’s Health Study |

| WLS | Weighted least squares |

| SASO | Sociedad Argentina de Superficie Ocular |

References

- Stapleton, F.; Argüeso, P.; Asbell, P.; Azar, D.; Bosworth, C.; Chen, W.; Ciolino, J.B.; Craig, J.P.; Gallar, J.; Galor, A.; et al. TFOS DEWS III: Digest. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2025, 279, 451–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.; Asbell, P.; Dogru, M.; Giannaccare, G.; Grau, A.; Gregory, D.; Kim, D.H.; Marini, M.C.; Ngo, W.; Nowinska, A.; et al. TFOS Lifestyle Report: Impact of environmental conditions on the ocular surface. Ocul. Surf. 2023, 29, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alryalat, S.A.; Toubasi, A.A.; Patnaik, J.L.; Kahook, M.Y. The impact of air pollution and climate change on eye health: A global review. Rev. Environ. Health 2022, 39, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tong, Y.; Cifuentes-González, C.; Agrawal, K.; Shakarchi, F.; Song, X.Y.R.; Ji, J.S.; Agrawal, R. Climate change and the impact on ocular infectious diseases: A narrative review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 1695–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, T.E.G.; Rorie, A.C.; Ramon, G.D.; Keswani, A.; Bernstein, J.; Codina, R.; Codispoti, C.; Craig, T.; Dykewicz, M.; Ferastraoaru, D.; et al. Impact of climate change on aerobiology, rhinitis, and allergen immunotherapy: Work Group Report from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2025, 155, 1767–1782.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, F.; Alves, M.; Bunya, V.Y.; Jalbert, I.; Lekhanont, K.; Malet, F.; Na, K.-S.; Schaumberg, D.; Uchino, M.; Vehof, J.; et al. TFOS DEWS II: Epidemiology Report. Ocul. Surf. 2017, 15, 334–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidet, J.R.; Chen, X.; Ræder, S.; Badian, R.A.; Utheim, T.P. Seasonal variations in presenting symptoms and signs of dry eye disease in Norway. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Li, G.; Zuo, Y.Y. Effect of Model Tear Film Lipid Layer on Water Evaporation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2023, 64, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, D.B.; Nag, N.; Tran, J.; Chen, L.B.; Visnagra, K.B.; Marshall, K.O.; Wade, M. A Novel Epidemiological Approach to Geographically Mapping Population Dry Eye Disease in the United States Through Google Trends. Cornea 2021, 40, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, P.K.; Kaushik, J.; Mathur, V.; Kumar, P.; Chauhan, N. Determining the effect of climate and profession on dry eye disease: A prevalence study among young males in north, north-west and central India. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2023, 79, S75–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSomali, A.I.; Alsaad, M.A.; Alshammary, A.A.; Al-Omair, A.M.; Alqahtani, R.M.; Almalki, A.S.; Alhejji, A.E.; Alqahtani, W.Y.; AlSomali, A.I.; Alsaad, M.A.; et al. Awareness About Dry Eye Symptoms and Risk Factors Among Eastern Province Population in Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2023, 15, e48197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabata, Y.; Terauchi, R.; Nakano, T. Seasonal variations and environmental influences on dry eye operations in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazreg, S.; Hosny, M.; Ahad, M.A.; Sinjab, M.M.; Messaoud, R.; Awwad, S.T.; Rousseau, A. Dry Eye Disease in the Middle East and Northern Africa: A Position Paper on the Current State and Unmet Needs. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2024, 18, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeze, N.S.; Jacob, J. Climate Change and Its Impact on Ocular Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e91614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, S.Y.; Wang, F.; Qiao, J.C.; Wang, X.-C.; Huang, Z.-H.; Yang, F.; Hu, C.-Y.; Tao, F.-B.; Tao, L.-M.; Liu, D.-W.; et al. Short-term effect of meteorological factors and extreme weather events on daily outpatient visits for dry eye disease between 2013 and 2020: A time-series study in Urumqi, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 111967–111981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papas, E.B. The global prevalence of dry eye disease: A Bayesian view. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 2021, 41, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britten-Jones, A.C.; Wang, M.T.M.; Samuels, I.; Jennings, C.; Stapleton, F.; Craig, J.P. Epidemiology and risk factors of dry eye disease: Considerations for clinical management. Medicina 2024, 60, 1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; McCann, P.; Lien, T.; Xiao, M.; Abraham, A.G.; Gregory, D.G.; Hauswirth, S.G.; Qureshi, R.; Liu, S.-H.; Saldanha, I.J.; et al. Prevalence of dry eye and Meibomian gland dysfunction in Central and South America: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2024, 24, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benítez-Del-Castillo, J.M.; Burgos-Blasco, B. Prevalence of dry eye disease in Spain: A population-based survey (PrevEOS). Ocul. Surf. 2025, 36, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münch, K.; Nöhre, M.; Westenberger, A.; Akkus, D.; Morfeld, M.; Brähler, E.; Framme, C.; de Zwaan, M. Prevalence and correlates of dry eye in a German population sample. Cornea 2024, 43, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, K.; Singh, S.; Singh, K.; Kumar, S.; Dwivedi, K. Prevalence of dry eye, its categorization (Dry Eye Workshop II), and pathological correlation: A tertiary care study. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 71, 1454–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, M.F.; Khalafalla, I.; Qarbote, A.I. Prevalence of dry eye disease in African populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Ophthalmol. 2025, 25, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.A.; Arantes, L.B.; Persona, E.L.S.; Garcia, D.M.; Persona, I.G.S.; Pontelli, R.C.N.; Rocha, E.M. Prevalence of dry eye in Brazil: Home survey reveals differences in urban and rural regions. Clinics 2025, 80, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jareebi, M.A.; Akkur, A.A.; Otayf, D.A.H.; Najmi, A.Y.; Mobarki, O.A.; Omar, E.Z.; Najmi, M.A.; Madkhali, A.Y.; Abu Alzawayid, N.A.N.; Darbeshi, Y.M.; et al. Exploring the prevalence of dry eye disease and its impact on quality of life in Saudi adults: A cross-sectional investigation. Medicina 2025, 61, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INDEC). National Census of Population, Households and Housing 2022; INDEC: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Marini, M.C.; Liviero, B.; Torres, R.M.; Galperin, G.; Galletti, J.G.; Alves, M. Epidemiology of dry eye disease in Argentina. Discov. Public Health 2024, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumberg, D.A.; Sullivan, D.A.; Buring, J.E.; Dana, M.R. Prevalence of dry eye syndrome among US women. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 136, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, M.; Miglio, M.; Keitelman, I.; Shiromizu, C.M.; Sabbione, F.; Fuentes, F.; Trevani, A.S.; Giordano, M.N.; Galletti, J.G. Transient tear hyperosmolarity disrupts the neuroimmune homeostasis of the ocular surface and facilitates dry eye onset. Immunology 2020, 161, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, E.J.; Ying, G.S.; Maguire, M.G.; Sheffield, P.E.; Szczotka-Flynn, L.B.; Asbell, P.A.; Shen, J.F. Climatic and Environmental Correlates of Dry Eye Disease Severity: A Report from the Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) Study. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, S.B.; Kim, N.H.; Lee, H.K.; Song, J.S.; Kim, H.C. Spatial epidemiology of dry eye disease: Findings from South Korea. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2014, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkoff, P.; Kjaergaard, S.K. The dichotomy of relative humidity on indoor air quality. Environ. Int. 2007, 33, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abusharha, A.A.; Pearce, E.I. The effect of low humidity on the human tear film. Cornea 2013, 32, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Miguel, A.; Tesón, M.; Martín-Montañez, V.; Enríquez-De-Salamanca, A.; Stern, M.E.; Calonge, M.; González-García, M.J. Dry eye exacerbation in patients exposed to desiccating stress under controlled environmental conditions. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2014, 157, 788–798.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendell, M.J.; Mirer, A.G.; Cheung, K.; Tong, M.; Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 748–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.T.; Chiu, C.Y.; Chang, S.W. Low ambient temperature correlates with the severity of dry eye symptoms. Taiwan J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 12, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; EMO Research Group. Symptoms of dry eye related to the relative humidity of living places. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2023, 46, 101865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Cuyo (n = 256) | Northeast (n = 836) | Northwest (n = 1060) | Pampas (n = 7457) | Patagonia (n = 1036) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DED, n (%) [95% CI] | 127 (49.8%) [95% CI: 43.5–55.7%] | 328 (39.2%) [95% CI: 36.0–42.6%] | 401 (37.7%) [95% CI: 35.0–40.8%] | 3173 (42.7%) [95% CI: 41.4–43.7%] | 435 (41.9%) [95% CI: 39.0–45.0%] | 0.001 |

| Women, % | 85 | 81 | 80 | 85 | 86 | 0.022 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 43.7 (15) | 41.9 (13) | 55.5 (14) | 46.5 (15) | 45.2 (13) | <0.001 |

| 12–20 years, n (%) | 6 (2.3) | 9 (1.1) | 9 (0.8) | 39 (0.5) | 13 (1.3) | 0.001 |

| 21–40 years, n (%) | 49 (19.1) | 155 (18.5) | 139 (13.1) | 1120 (15.0) | 147 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| 41–60 years, n (%) | 52 (20.3) | 136 (16.3) | 199 (18.8) | 1425 (19.1) | 208 (20.1) | 0.125 |

| >60 years, n (%) | 20 (7.8) | 28 (3.3) | 54 (5.1) | 586 (7.9) | 67 (6.5) | <0.001 |

| Relative humidity, % | 55.1 | 80.6 | 72.6 | 68.3 | 67.0 | <0.001 |

| Mean temperature, °C | 18.6 | 21.6 | 19.6 | 17.8 | 10.8 | <0.001 |

| Max. temperature, °C | 26.1 | 26.3 | 26.0 | 24.0 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Min. temperature, °C | 11.1 | 17.0 | 13.3 | 11.5 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Model | Covariates | RH Slope (pp per + 1% RH) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RH (%) | −0.409 | Regions with higher RH tended to show lower DED prevalence. |

| 2 | RH (%), Mean age (years) | −0.407 | Adjustment for age did not materially change the RH–DED pattern. |

| 3 | RH (%), Women (%) | −0.252 | Adjustment for the proportion of women attenuated the RH–DED gradient. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marini, M.C.; Liviero, B.; Torres, R.M.; Galletti, J.G.; Galperin, G.; Alves, M.; Merayo-Lloves, J. Temperature, Humidity and Regional Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease in Argentina. Medicina 2025, 61, 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122226

Marini MC, Liviero B, Torres RM, Galletti JG, Galperin G, Alves M, Merayo-Lloves J. Temperature, Humidity and Regional Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease in Argentina. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122226

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarini, María C., Belén Liviero, Rodrigo M. Torres, Jeremías G. Galletti, Gustavo Galperin, Monica Alves, and Jesús Merayo-Lloves. 2025. "Temperature, Humidity and Regional Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease in Argentina" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122226

APA StyleMarini, M. C., Liviero, B., Torres, R. M., Galletti, J. G., Galperin, G., Alves, M., & Merayo-Lloves, J. (2025). Temperature, Humidity and Regional Prevalence of Dry Eye Disease in Argentina. Medicina, 61(12), 2226. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122226