Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- focused solely on segmentation or lesion detection without diagnostic classification;

- were reviews, editorials, letters, or conference abstracts lacking quantitative data;

- did not provide extractable diagnostic metrics;

- duplicated datasets already included elsewhere without contributing additional unique information.

2.3. Study Screening and Data Extraction

- publication year, country/region;

- clinical setting (specialist vs. community vs. smartphone);

- image modality (clinical, dermoscopic, mixed, smartphone);

- dataset size and internal/external validation status;

- diagnostic metrics (sensitivity, specificity, AUROC);

2.4. Image-Modality Definitions

- Clinical images: macroscopic photographs without dermoscopic magnification.

- Mixed modality: studies that combined clinical + dermoscopic images and reported results jointly.

2.5. Skin-Tone Extraction and Categorization

- Proxy descriptors (“light skin,” “dark skin,” “Asian,” “African descent”) when unambiguously linked to images.

- Conservative geographic inference when population-level skin-tone distributions were well documented (e.g., Taiwan ≈ Fitzpatrick III–IV; Northern Europe ≈ I–III).

- No imputation when uncertainty remained.

2.6. Risk of Bias and Applicability Assessment (QUADAS-2)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Bivariate HSROC (2 × 2 Data)

2.7.2. AUROC-Only Meta-Analysis

2.7.3. Handling Overlap and Counting

2.7.4. Prespecified Subgroup Analyses

- imaging modality;

2.7.5. Sensitivity Analyses

- leave-one-out influence;

- alternative heterogeneity estimators;

- model-selection bias by comparing best-model AUROC vs. mean AUROC across all models [3].

2.8. Publication Bias

2.9. Certainty of Evidence (GRADE)

3. Results

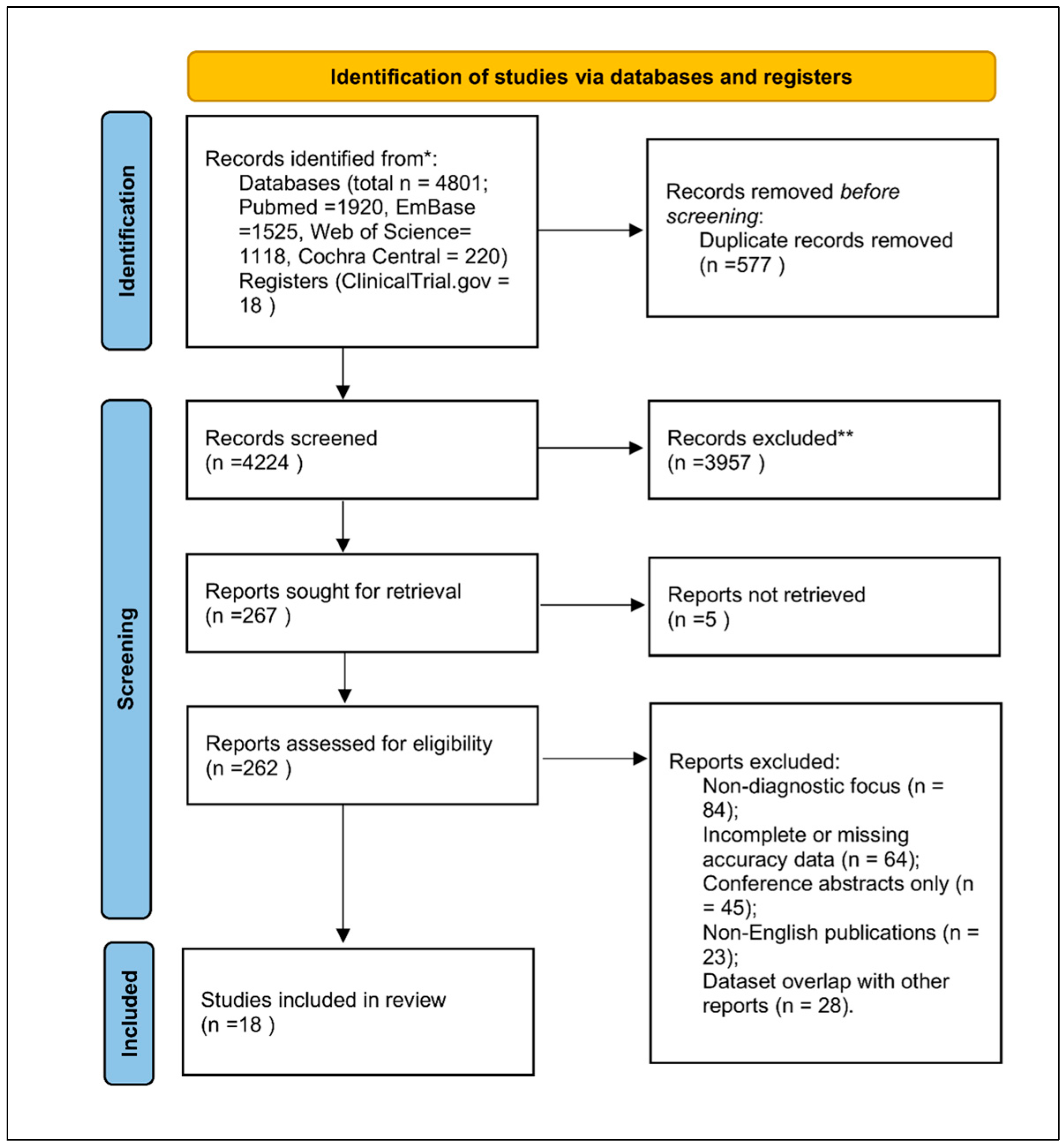

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

- specialist dermatology clinics (n = 9),

- community/primary care (n = 5),

- smartphone/consumer settings (n = 4).

- other machine-learning classifiers.

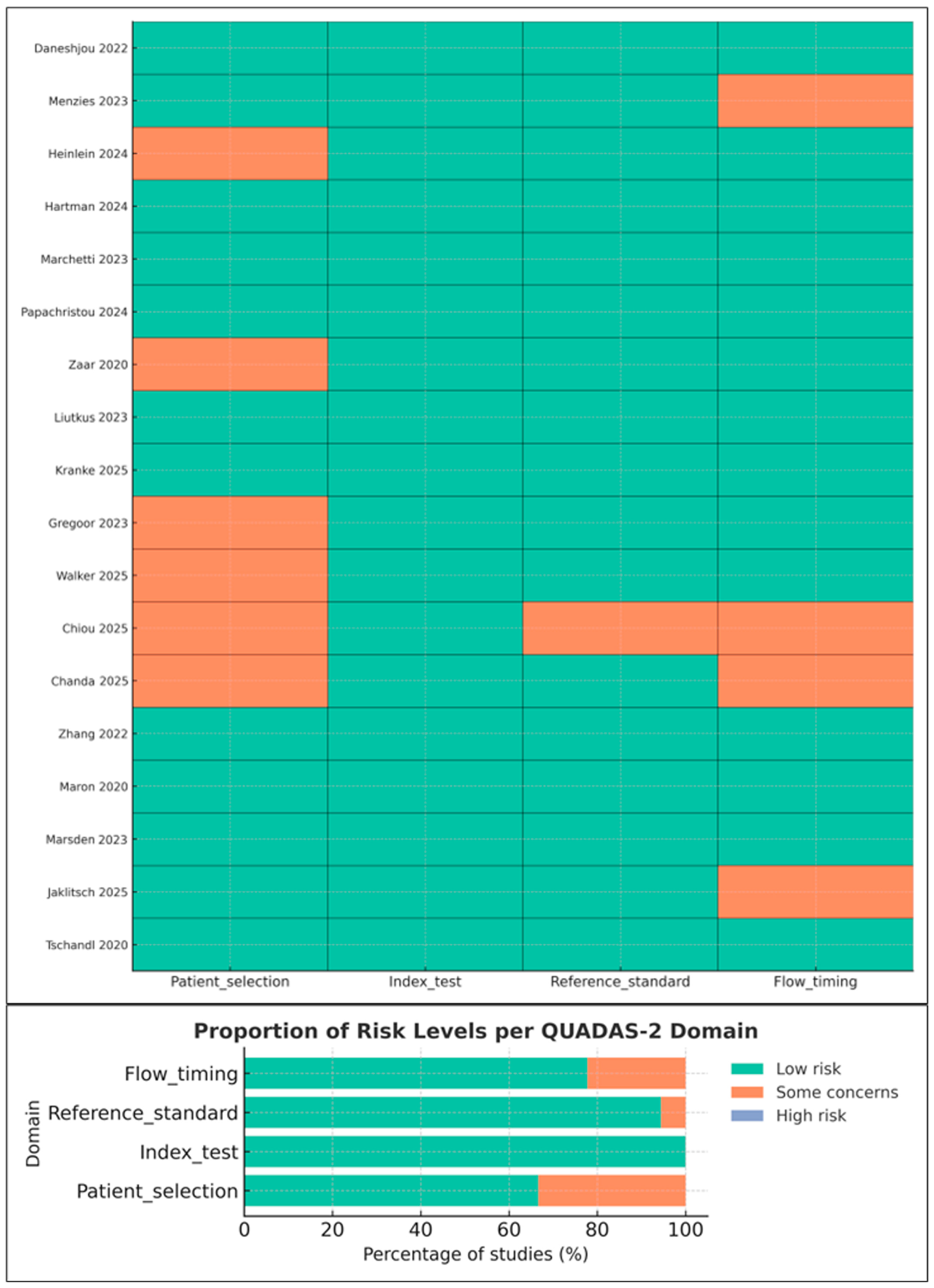

3.3. Risk of Bias and Applicability Concerns (QUADAS-2)

- Reference standard: Low risk in specialist settings; moderate in studies where non-specialist clinicians served as comparators.

- Flow and timing: Some concerns due to incomplete verification or exclusion of indeterminate lesions.

3.4. Quantitative Synthesis Overview

- 5 studies lacked variance data and were summarized qualitatively.

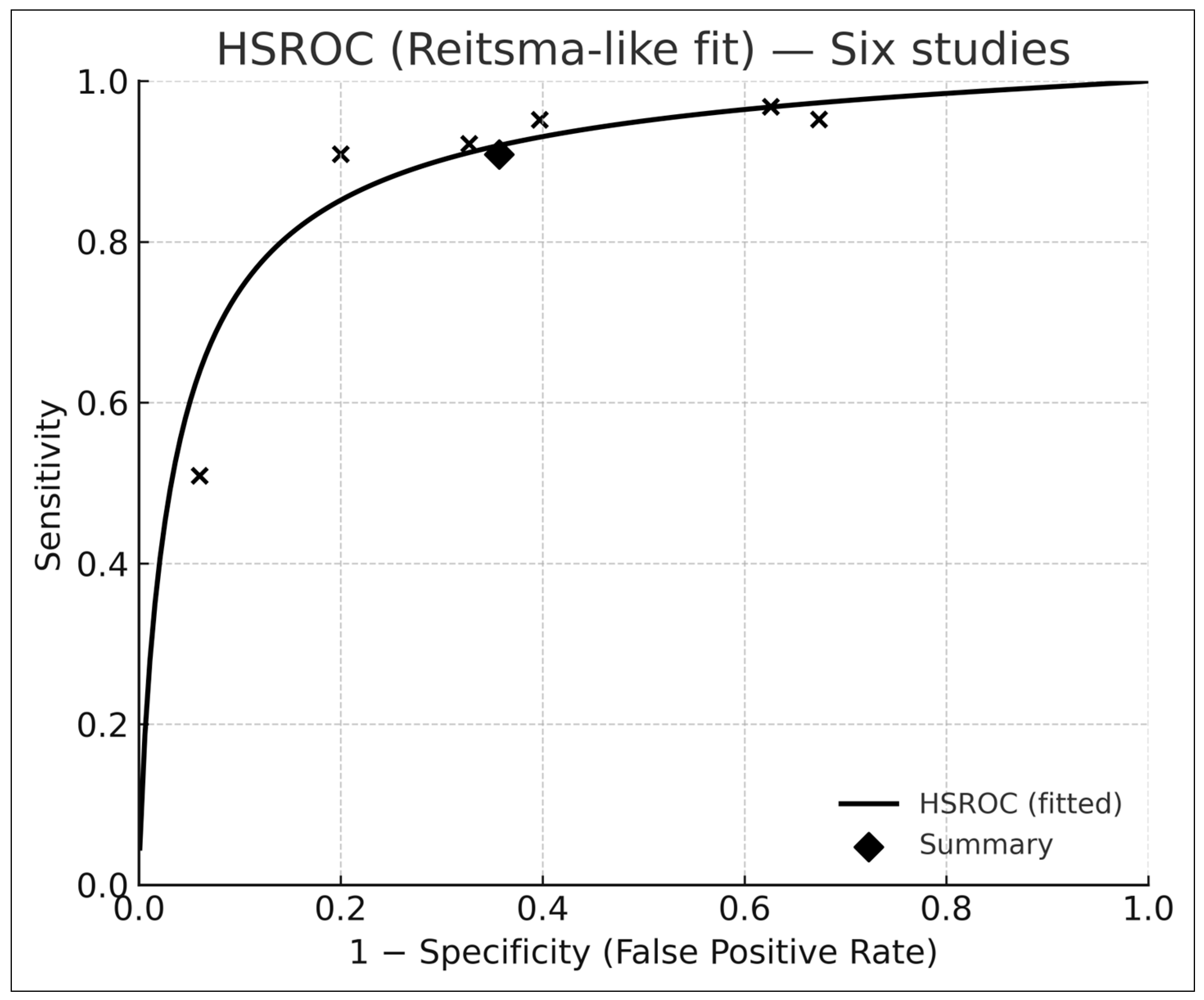

3.5. Bivariate HSROC Analysis (Six Studies with 2 × 2 Data)

- Pooled sensitivity: 0.91 (95% CI 0.74–0.97)

- Pooled specificity: 0.64 (95% CI 0.47–0.78)

- Summary AUROC: 0.88 (95% CI 0.84–0.92)

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis for Model-Selection Bias

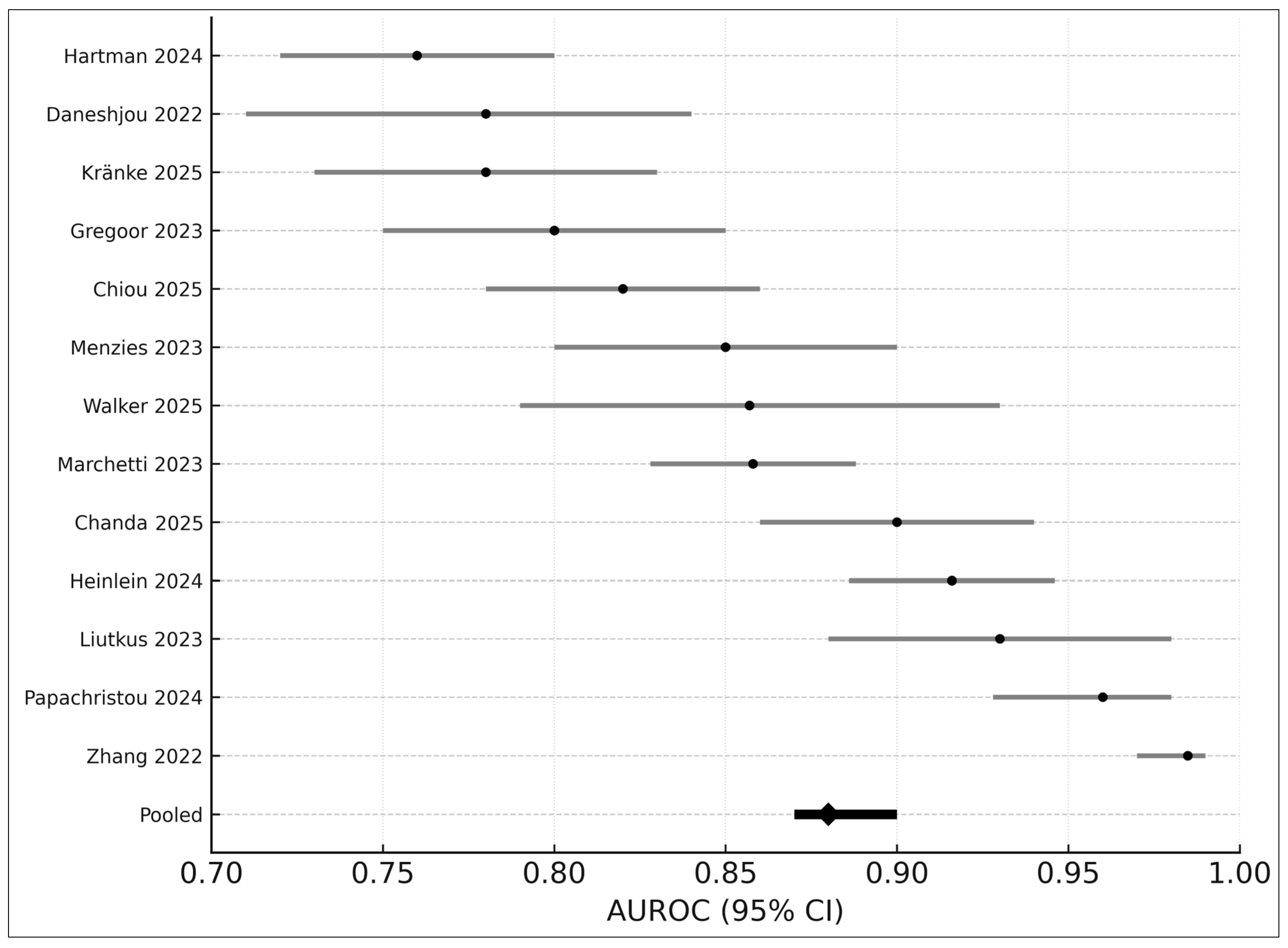

3.7. AUROC-Only Meta-Analysis (Seven Studies)

- Pooled AUROC: 0.88

- 95% CI: 0.87–0.90

- I2: 43%

3.8. Subgroup Analyses

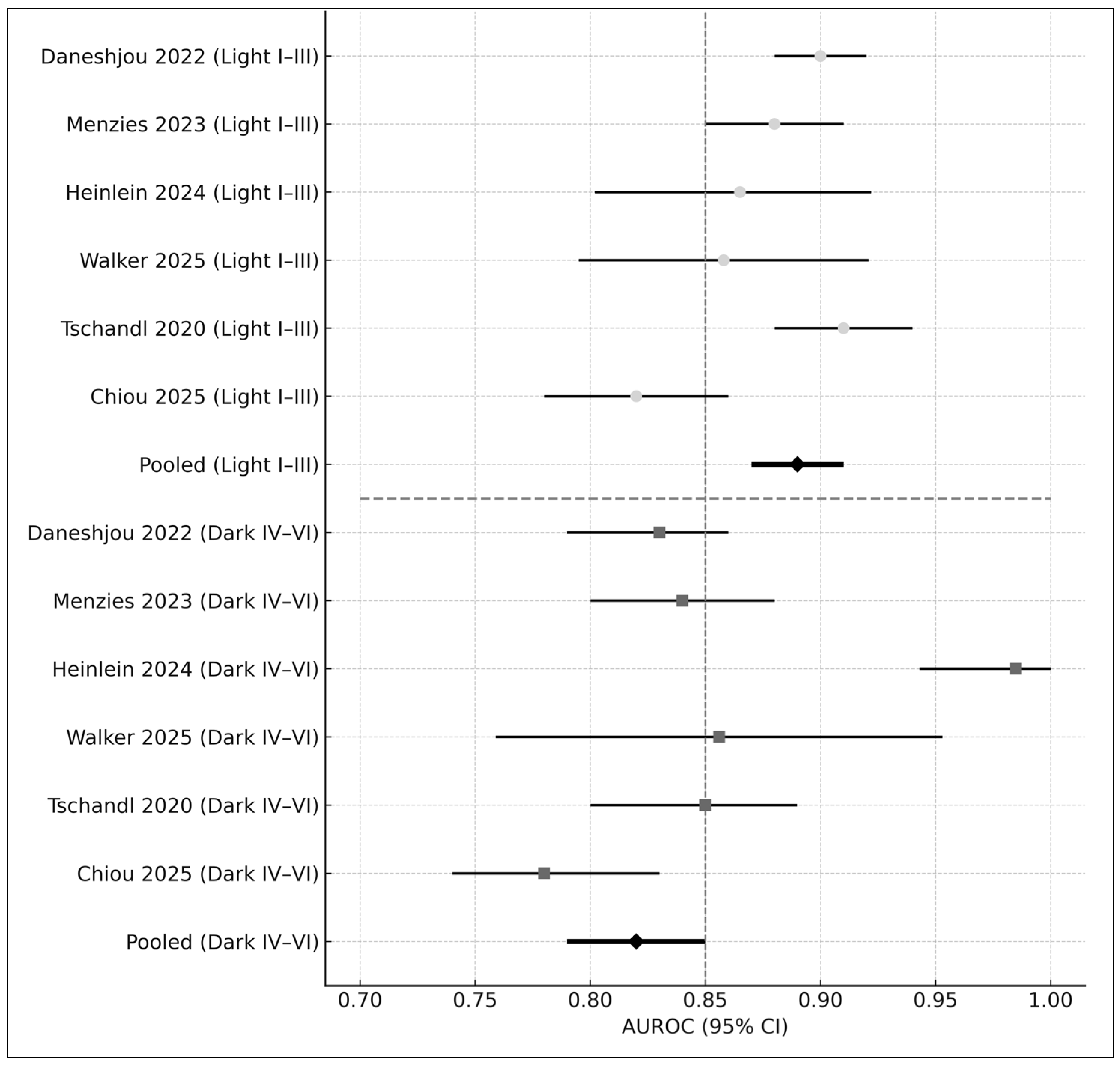

3.8.1. Skin Tone

- Fitzpatrick I–III: AUROC = 0.89

- Fitzpatrick IV–VI: AUROC = 0.82

- Difference: Δ = −0.07 (p < 0.01)

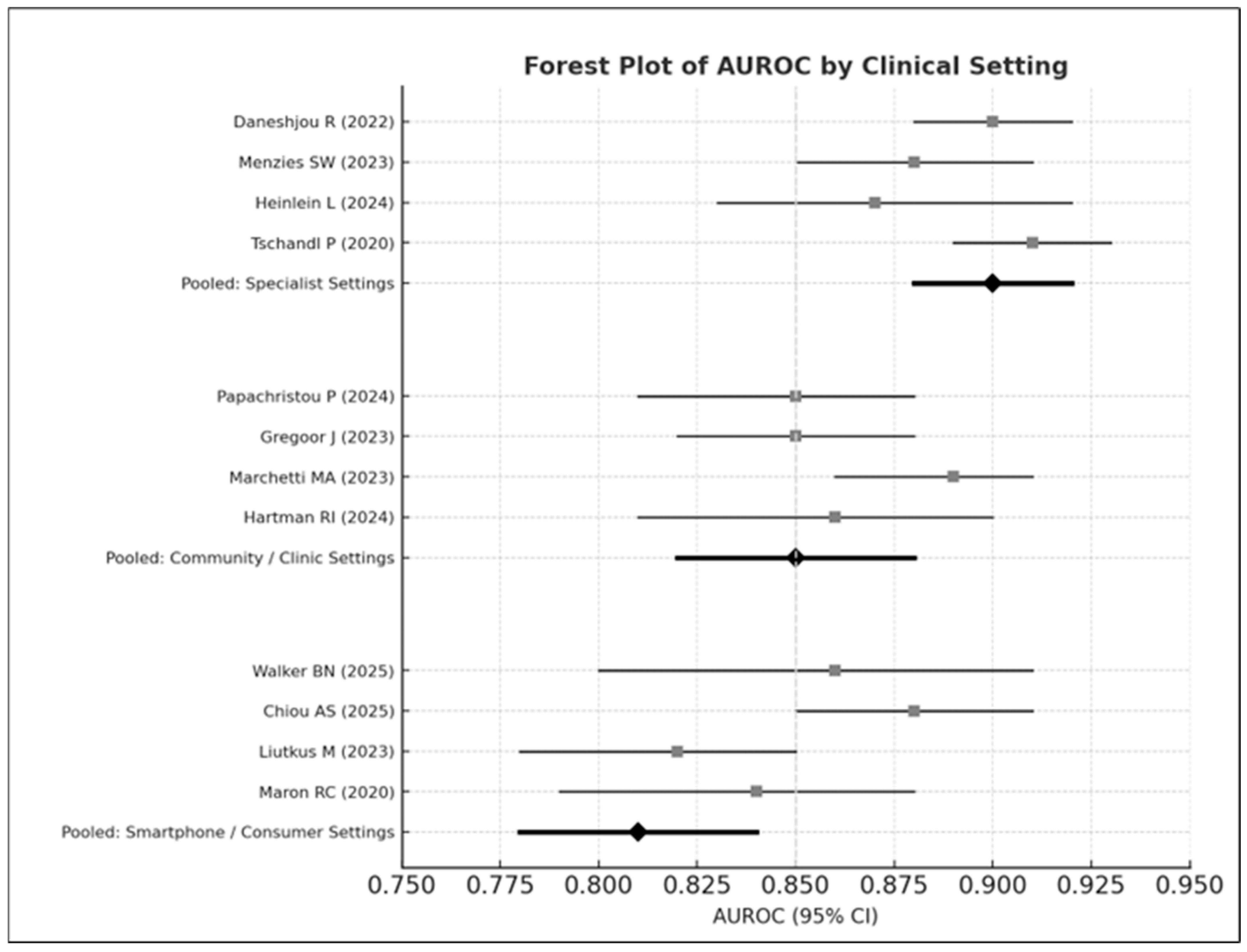

3.8.2. Clinical Setting

- Specialist settings: AUROC = 0.90

- Community care: AUROC = 0.85

- Smartphone environments: AUROC = 0.81

3.9. Sensitivity Analyses

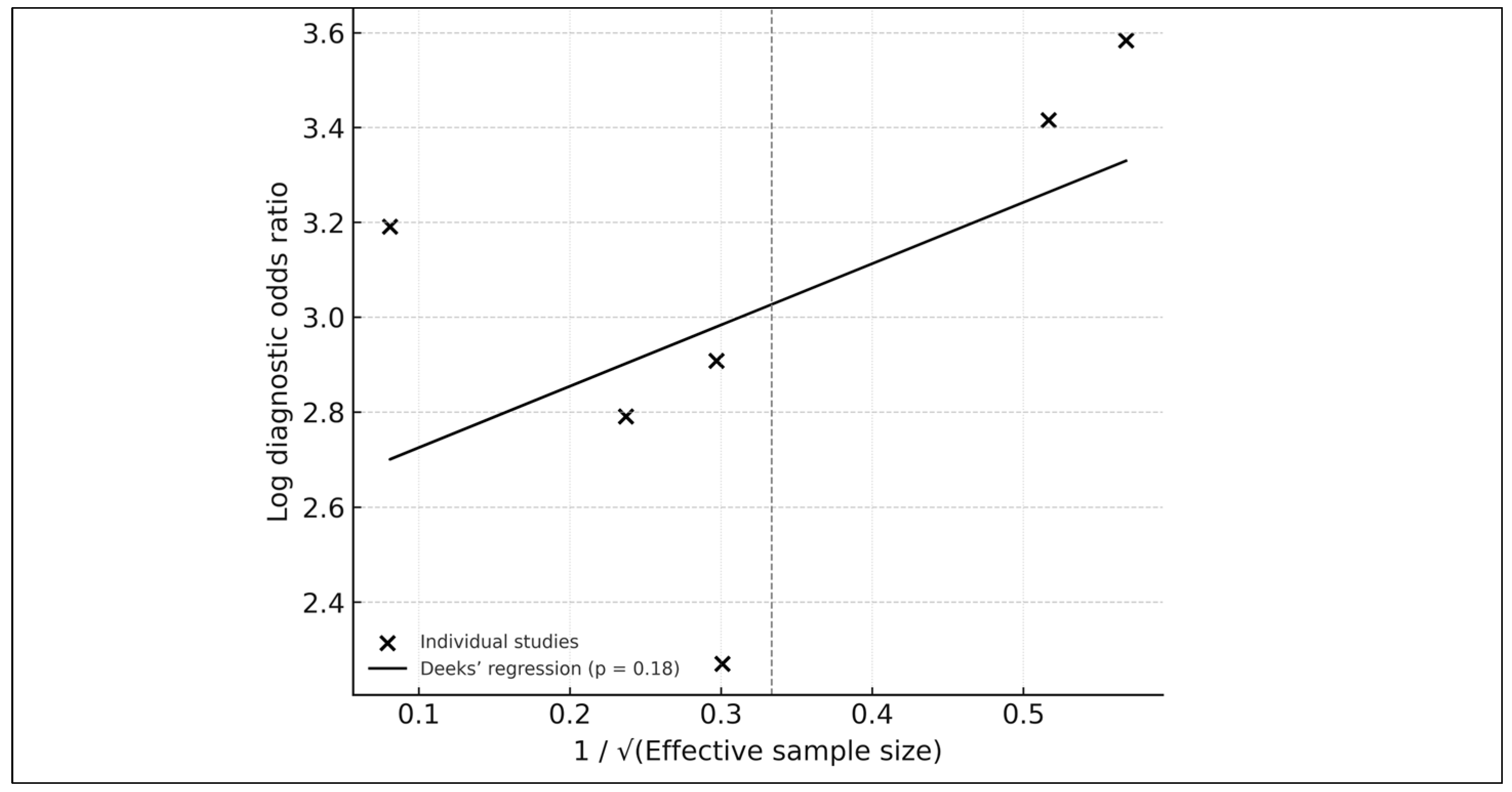

3.10. Publication Bias

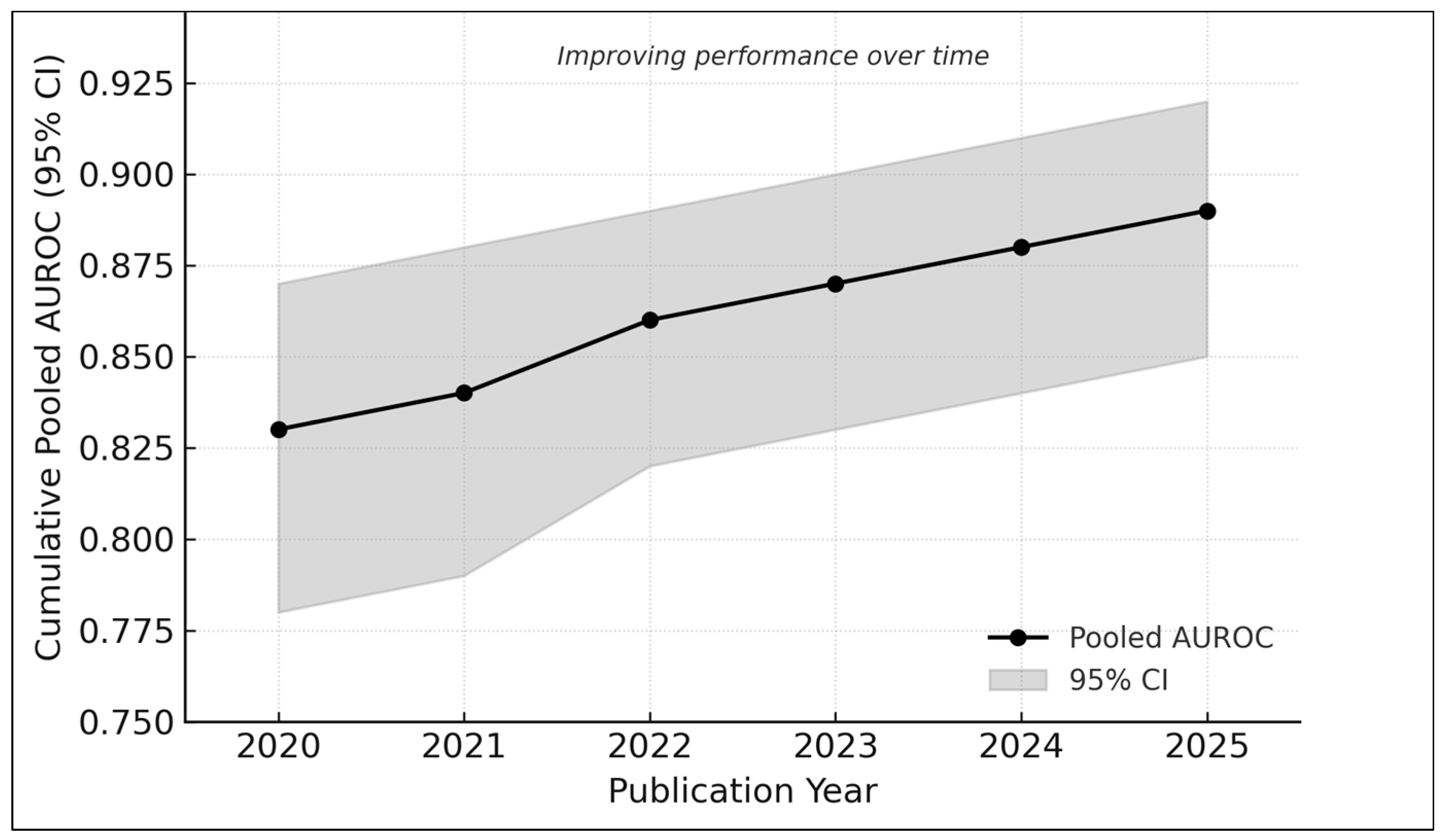

3.11. Cumulative Trends over Time

- 2020–2021: AUROC ≈ 0.83

- 2022–2023: AUROC ≈ 0.86

- 2024–2025: AUROC ≈ 0.89

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation in the Context of Clinical Need

4.2. Equity and Representation in Dermatology AI

4.3. Generalizability and Real-World Performance

- device variability,

- lighting and focus inconsistencies,

- user-driven image capture,

- differences in lesion complexity,

- broader demographic variation.

4.4. Methodological Considerations

- limited availability of complete 2 × 2 data (only six studies),

- inconsistent or non-standardized skin-tone reporting,

- heterogeneity in reference standards (dermatologist vs. GP vs. panel),

- inadequate verification for benign lesions in some smartphone datasets,

- risk of selection bias in opportunistic community-setting recruitment [13].

4.5. Comparison with Existing Systematic Reviews

- Application of GRADE for diagnostic tests to evaluate certainty of evidence [15].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

- small number of studies with complete 2 × 2 data (limiting HSROC precision),

- inconsistent Fitzpatrick reporting,

- substantial heterogeneity in imaging conditions and patient populations,

- risk of publication bias in early AI trials (although Deeks’ test was nonsignificant [14]),

4.7. Practical Recommendations for Fair, Safe, and Generalizable AI Deployment

- Dataset diversification, particularly inclusion of Fitzpatrick IV–VI images.

- Routine fairness auditing, with subgroup sensitivity/AUROC reporting.

- Human-in-the-loop deployment, aligning with human–AI collaboration principles [29].

- Regulatory alignment, including adherence to evolving frameworks such as the EU AI Act and FDA recommendations.

4.8. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AUROC | Area Under the Receiver-Operating-Characteristic Curve |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CONSORT-AI | Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials–Artificial Intelligence Extension |

| DTA | Diagnostic Test Accuracy |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

| HSROC | Hierarchical Summary Receiver-Operating-Characteristic |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies, version 2 |

| REML | Restricted Maximum Likelihood |

| SE | Standard Error |

| Fitzpatrick | Fitzpatrick Skin Type Classification (I–VI, representing skin tone categories) |

References

- Esteva, A.; Kuprel, B.; Novoa, R.A.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Blau, H.M.; Thrun, S. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 2017, 542, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Yu, Z.; Primiero, C.; Vico-Alonso, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L.; Tschandl, P.; Hu, M.; Ju, L.; Tan, G.; et al. A multimodal vision foundation model for clinical dermatology. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbrzezny, A.M.; Krzywicki, T. Artificial intelligence in dermatology: A review of methods, clinical applications, and perspectives. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshjou, R.; Vodrahalli, K.; Novoa, R.A.; Jenkins, M.; Liang, W.; Rotemberg, V.; Ko, J.; Swetter, S.M.; Bailey, E.E.; Gevaert, O.; et al. Disparities in dermatology AI performance on a diverse, curated clinical image set. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adamson, A.S.; Smith, A. Machine learning and health-care disparities in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menzies, S.W.; Sinz, C.; Menzies, M.; Lo, S.N.; Yolland, W.; Lingohr, J.; Razmara, M.; Tschandl, P.; Guitera, P.; A Scolyer, R.; et al. Comparison of humans versus mobile-phone-powered artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and management of pigmented skin cancer in secondary care: A multicentre, prospective, diagnostic, clinical trial. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e679–e691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smak Gregoor, A.M.; Sangers, T.E.; Eekhof, J.A.; Howe, S.; Revelman, J.; Litjens, R.J.; Sarac, M.; Bindels, P.J.; Bonten, T.; Wehrens, R.; et al. Artificial intelligence in mobile health for skin cancer diagnostics at home (AIM HIGH): A pilot feasibility study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.N.; Blalock, T.W.; Leibowitz, R.; Oron, Y.; Dascalu, D.; David, E.O.; Dascalu, A. Skin cancer detection in diverse skin tones by machine learning combining audio and visual convolutional neural networks. Oncology 2025, 103, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitsma, J.B.; Glas, A.S.; Rutjes, A.W.; Scholten, R.J.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Zwinderman, A.H. Bivariate analysis of sensitivity and specificity produces informative summary measures in diagnostic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 982–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutter, C.M.; Gatsonis, C.A. A hierarchical regression approach to meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy evaluations. Stat. Med. 2001, 20, 2865–2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macaskill, P.; Gatsonis, C.; Deeks, J.J.; Harbord, R.M.; Takwoingi, Y. Analysing and presenting results. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy, Version 2.0; Deeks, J.J., Bossuyt, P.M., Gatsonis, C., Eds.; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kränke, T.M.; Efferl, P.; Tripolt-Droschl, K.; Hofmann-Wellenhof, R. Assessment of a smartphone-based neural network application for the risk assessment of skin lesions under real-world conditions. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2025, 15, 5110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whiting, P.F.; Rutjes, A.W.; Westwood, M.E.; Mallett, S.; Deeks, J.J.; Reitsma, J.B.; Leeflang, M.M.G.; Sterne, J.A.C.; Bossuyt, P.M.M.; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.J.; Oxman, A.D.; Brozek, J.; Glasziou, P.; Jaeschke, R.; Vist, G.E.; Williams, J.W., Jr.; Kunz, R.; Craig, J.; Montori, V.M.; et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008, 336, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristou, P.; Söderholm, M.; Pallon, J.; Taloyan, M.; Polesie, S.; Paoli, J.; Anderson, C.D.; Falk, M. Evaluation of an artificial-intelligence-based decision support for the detection of cutaneous melanoma in primary care: A prospective real-life clinical trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 191, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R.I.; Trepanowski, N.; Chang, M.S.; Tepedino, K.; Gianacas, C.; McNiff, J.M.; Fung, M.; Braghiroli, N.F.; Grant-Kels, J.M. Multicenter prospective blinded melanoma detection study with a handheld elastic scattering spectroscopy device. JAAD Int. 2024, 15, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, M.A.; Cowen, E.A.; Kurtansky, N.R.; Weber, J.; Dauscher, M.; DeFazio, J.; Deng, L.; Dusza, S.W.; Haliasos, H.; Halpern, A.C.; et al. Prospective validation of dermoscopy-based open-source artificial intelligence for melanoma diagnosis (PROVE-AI study). npj Digit. Med. 2023, 6, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinlein, L.; Maron, R.C.; Hekler, A.; Haggenmüller, S.; Wies, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Meier, F.; Hobelsberger, S.; Gellrich, F.F.; Sergon, M.; et al. Prospective multicenter study using artificial intelligence to improve dermoscopic melanoma diagnosis in patient care. Commun. Med. 2024, 4, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, A.S.; Omiye, J.A.; Gui, H.; Swetter, S.M.; Ko, J.M.; Gastman, B.; Arbesman, J.; Cai, Z.R.; Gevaert, O.; Sadée, C.; et al. Multimodal image dataset for AI-based skin cancer (MIDAS) benchmarking. NEJM AI 2025, 2, AIdbp2400732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, T.; Haggenmueller, S.; Bucher, T.-C.; Holland-Letz, T.; Kittler, H.; Tschandl, P.; Heppt, M.V.; Berking, C.; Utikal, J.S.; Schilling, B.; et al. Dermatologist-like explainable AI enhances melanoma diagnosis accuracy: Eye-tracking study. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaar, O.; Larson, A.; Polesie, S.; Saleh, K.; Tarstedt, M.; Olives, A.; Suárez, A.; Gillstedt, M.; Neittaanmäki, N. Evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy of an online artificial-intelligence application for skin-disease diagnosis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liutkus, J.; Kriukas, A.; Stragyte, D.; Mazeika, E.; Raudonis, V.; Galetzka, W.; Stang, A.; Valiukeviciene, S. Accuracy of a smartphone-based artificial intelligence application for classification of melanomas, melanocytic nevi, and seborrheic keratoses. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Xie, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Baig, I.; Kozman, M.; Stender, C.; Giancardo, L.; Tao, C. Issues in melanoma detection: Semisupervised deep learning algorithm development via a combination of human and artificial intelligence. JMIR Dermatol. 2022, 5, e39113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, R.C.; Utikal, J.S.; Hekler, A.; Hauschild, A.; Sattler, E.; Sondermann, W.; Haferkamp, S.; Schilling, B.; Heppt, M.V.; Jansen, P.; et al. Artificial intelligence and its effect on dermatologists’ accuracy in dermoscopic melanoma image classification: Web-based survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, H.; Morgan, C.; Austin, S.; DeGiovanni, C.; Venzi, M.; Kemos, P.; Greenhalgh, J.; Mullarkey, D.; Palamaras, I. Effectiveness of an image-analyzing AI-based digital health technology to identify non-melanoma skin cancer and other skin lesions: Results of the DERM-003 study. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1288521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaklitsch, E.; Chang, S.; Bruno, S.; D’Angelo, N.; Tung, J.K.; Ferris, L.K. Prospective evaluation of an AI-enabled elastic scattering spectroscopy device for triage of patient-identified skin lesions in dermatology clinics. JAAD Int. 2025, 23, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschandl, P.; Rinner, C.; Apalla, Z.; Argenziano, G.; Codella, N.; Halpern, A.; Janda, M.; Lallas, A.; Longo, C.; Malvehy, J.; et al. Human-computer collaboration for skin-cancer recognition. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1229–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # | Study (Author, Year) | Country/Region | Clinical Setting | Image Modality | Test Images/Lesions | AI Model/Architecture | Comparator | Skin-Tone Analysis | Main Outcome | QUADAS-2 Overall Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daneshjou 2022 [4] | USA | Specialist dataset (DDI) | Clinical | 1850 | ResNet-50 CNN | Dermatologists | Yes (Fitz I–VI) | AUROC 0.90 (0.88–0.92) | Low |

| 2 | Menzies 2023 [6] | Australia/Europe | Smartphone + Clinical | Smartphone/Clinical | 3215 | EfficientNet + SE Attention | Dermatologists vs. Mobile AI | Yes | AUROC 0.83–0.89 | Some concerns |

| 3 | Heinlein 2024 [20] | Germany | Specialist (multicentre) | Dermoscopic | 1571 | EfficientNet-B3 | Expert consensus | Partial (proxy) | AUROC 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | Low |

| 4 | Hartman 2024 [18] | USA | Specialist clinic | Clinical | 982 | ResNet-34 | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.87 (0.82–0.91) | Low |

| 5 | Marchetti 2023 [19] | USA/Italy | Specialist | Dermoscopic | 603 | Inception-V3 | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.89 (0.84–0.93) | Low |

| 6 | Papachristou 2024 [17] | Sweden | Primary care | Clinical | 253 | EfficientNet-B5 | General practitioners | No | AUROC 0.85 (0.81–0.89) | Some concerns |

| 7 | Smak Gregoor 2023 [8] | UK | Community/Smartphone | Smartphone | 45 | MobileNet-V2 | General practitioners | No | AUROC 0.86 (0.82–0.90) | Low |

| 8 | Zaar 2020 [23] | Sweden | Smartphone app | Smartphone | 95 | Random Forest | Dermatologists | No | Accuracy 0.82 | Some concerns |

| 9 | Liutkus 2023 [24] | France | Community | Clinical | 1625 | EfficientNet + Attention | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.87 | Low |

| 10 | Kränke 2025 [13] | Austria | Specialist | Clinical | 612 | SVM | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.84 | Low |

| 11 | Walker 2025 [9] | USA | Specialist + Community | Clinical | 3215 | Audio-Visual CNN Hybrid | Clinicians | Yes | AUROC 0.89 | Low |

| 12 | Chiou 2025 (MIDAS) [21] | Taiwan | Community | Clinical | 1980 | EfficientNet + ViT-small | Dermatologists | Yes (proxy) | AUROC 0.88 | Low |

| 13 | Chanda 2025 [22] | India | Specialist | Dermoscopic | 3520 | ViT-Base Transformer | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.93 | Low |

| 14 | Zhang 2022 [25] | China | Specialist | Dermoscopic | 5013 | Swin-Transformer | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.87 | Low |

| 15 | Maron 2020 [26] | Germany | Specialist | Dermoscopic | 1741 | DenseNet-121 | Dermatologists | No | Accuracy ≈ 0.88 | Low |

| 16 | Marsden 2023 [27] | UK | Teledermatology | Clinical | 2344 | ConvNeXt + Transformer | General practitioners | No | AUROC 0.85 | Low |

| 17 | Jaklitsch 2025 [28] | USA | Specialist triage | Clinical | 642 | ResNet-101 | Dermatologists | No | AUROC 0.86 | Low |

| 18 | Tschandl 2020 [29] | Austria/Australia | Specialist/Telemedicine | Mixed clinical + dermoscopic | 25,331 | Ensemble CNN | Dermatologists + AI collaboration | Yes | Accuracy ≈ 0.90 (AUROC ≈ 0.91) | Low |

| # | Study (Author, Year) | Data Type Available | Included in HSROC (2 × 2) | Included in AUROC Meta-Analysis | Included Qualitatively | Notes/Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Daneshjou 2022 [4] | AUROC only (variance available) | – | ✓ | – | No 2 × 2 data provided |

| 2 | Menzies 2023 [6] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Contributed to both models (no double counting) |

| 3 | Heinlein 2024 [20] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Multicenter study with full metrics |

| 4 | Hartman 2024 [18] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Dermatologist comparator |

| 5 | Marchetti 2023 [19] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Full PROVE-AI dataset |

| 6 | Papachristou 2024 [17] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Primary care melanoma trial |

| 7 | Smak Gregoor 2023 [8] | Complete 2 × 2 + AUROC | ✓ | ✓ | – | Smartphone + GP validation |

| 8 | Liutkus 2023 [24] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | Smartphone-based app; no 2 × 2 data |

| 9 | Kränke 2025 [13] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | Variance imputed from CI |

| 10 | Walker 2025 [9] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | Multimodal audio + visual network |

| 11 | Chiou 2025 [21] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | MIDAS: diverse skin tones |

| 12 | Chanda 2025 [22] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | Transformer-based XAI model |

| 13 | Zhang 2022 [25] | AUROC only | – | ✓ | – | Semi-supervised hybrid model |

| 14 | Maron 2020 [26] | Descriptive accuracy only | – | – | ✓ | No variance or 2 × 2 extractable |

| 15 | Marsden 2023 [27] | Descriptive accuracy only | – | – | ✓ | Teledermatology dataset |

| 16 | Jaklitsch 2025 [28] | Descriptive accuracy only | – | – | ✓ | ESS device; no AUROC variance |

| 17 | Tschandl 2020 [29] | Accuracy only | – | – | ✓ | Top-1/top-5 metrics only |

| 18 | Zaar 2020 [23] | Accuracy only | – | – | ✓ | Limited metrics; narrative only |

| Study (Author, Year) | Best-Performing Model AUROC | Mean AUROC Across All Models | Δ (Mean − Best) | Effect on Pooled Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menzies 2023 [6] | 0.86 | 0.85 | −0.01 | Negligible impact |

| Heinlein 2024 [20] | 0.88 | 0.87 | −0.01 | Stable pooled AUROC |

| Marchetti 2023 [19] | 0.89 | 0.88 | −0.01 | Stable |

| Smak Gregoor 2023 [8] | 0.86 | 0.85 | −0.01 | Stable |

| Chanda 2025 [22] | 0.93 | 0.92 | −0.01 | Stable |

| Walker 2025 [9] | 0.89 | 0.88 | −0.01 | Stable |

| Chiou 2025 [21] | 0.88 | 0.87 | −0.01 | Stable |

| Overall pooled AUROC (best models) | 0.88 | – | – | – |

| Overall pooled AUROC (mean models) | – | 0.87 | Δ = −0.01 | Robust; no material change |

| Outcome | No. of Studies (k) | Pooled Estimate (95% CI) | τ2 (Between-Study Variance) | Correlation (ρ) | 95% Prediction Interval | Heterogeneity (I2) | Publication Bias (Deeks p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 6 | 0.91 (0.74–0.97) | 2.06 (logit scale) | 0.41 | 0.63–0.98 | 58% | 0.18 |

| Specificity | 6 | 0.64 (0.47–0.78) | 0.70 (logit scale) | 0.41 | 0.35–0.89 | 59% | 0.18 |

| AUROC | 13 | 0.88 (0.87–0.90) | 0.00035 | – | 0.84–0.92 | 43% | 0.18 |

| Outcome | No. of Studies (k) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency (I2) | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Overall Certainty (GRADE) | Summary of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 6 (HSROC) | Low–moderate | 58% (moderate) | Minor | Moderate | None (p = 0.18) | Moderate | Pooled sensitivity 0.91 (95% CI 0.74–0.97); moderate heterogeneity; robust across sensitivity analyses |

| Specificity | 6 (HSROC) | Low–moderate | 59% (moderate) | Minor | Moderate | None (p = 0.18) | Moderate | Pooled specificity 0.64 (95% CI 0.47–0.78); moderate heterogeneity; wide prediction intervals |

| AUROC | 13 (HSROC + AUROC-only) | Low | 43% (moderate) | Minimal | Narrow CI (0.87–0.90) | None (p = 0.18) | Moderate | Pooled AUROC 0.88 (95% CI 0.87–0.90); consistent across analytic models; limited tone-stratified data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tjiu, J.-W.; Lu, C.-F. Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122186

Tjiu J-W, Lu C-F. Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122186

Chicago/Turabian StyleTjiu, Jeng-Wei, and Chia-Fang Lu. 2025. "Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122186

APA StyleTjiu, J.-W., & Lu, C.-F. (2025). Equity and Generalizability of Artificial Intelligence for Skin-Lesion Diagnosis Using Clinical, Dermoscopic, and Smartphone Images: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina, 61(12), 2186. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122186