Differential Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alcoholic Versus Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

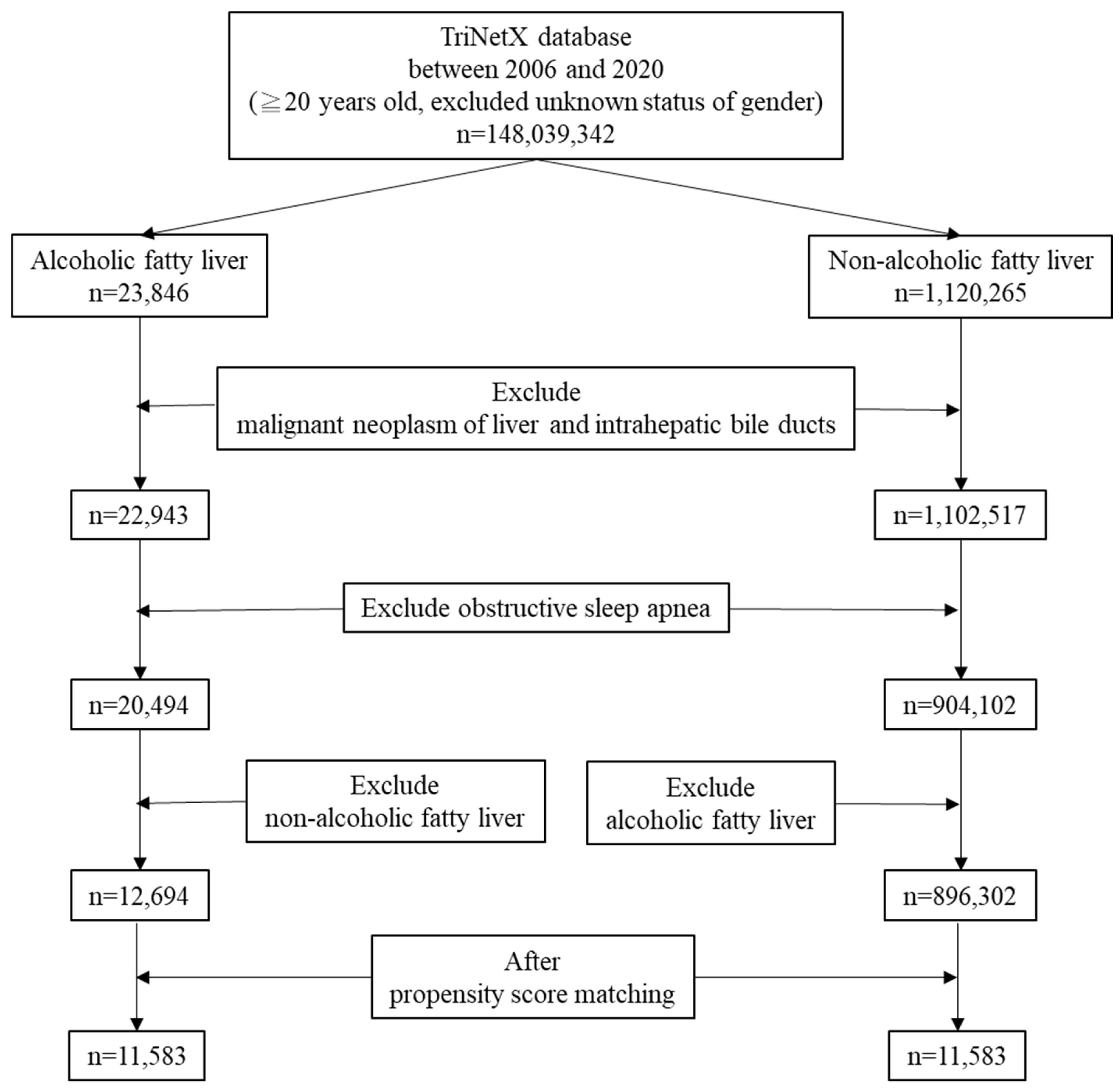

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkhouri, N.; Almomani, A.; Le, P.; Payne, J.Y.; Asaad, I.; Sakkal, C.; Vos, M.; Noureddin, M.; Kumar, P. The prevalence of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescents and young adults in the United States: Analysis of the NHANES database. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022, 22, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Hirode, G.; Singal, A.K.; Sundaram, V.; Wong, R.J. Alcoholic liver disease epidemiology in the United States: A retrospective analysis of 3 US databases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Cho, Y.K.; Cho, J.; Jung, H.S.; Yun, K.E.; Ahn, J.; Sohn, C.I.; Shin, H.; Ryu, S. Alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver-related mortality: A cohort study. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 114, 620–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Koenig, A.B.; Abdelatif, D.; Fazel, Y.; Henry, L.; Wymer, M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016, 64, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M.L.; Ng, C.H.; Huang, D.Q.; Chan, K.E.; Tan, D.J.; Lim, W.H.; Yang, J.D.; Tan, E.; Muthiah, M.D. Global incidence and prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2023, 29 (Suppl.), S32–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, Y.; Fu, X.; Mu, C.; Yao, M.; Ni, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z. Estimating global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease from 2000 to 2021: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1682–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Le, M.H.; Le, D.M.; Baez, T.C.; Wu, Y.; Ito, T.; Lee, E.Y.; Lee, K.; Stave, C.D.; Henry, L.; Barnett, S.D.; et al. Global incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 63 studies and 1,201,807 persons. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taveira, K.V.M.; Kuntze, M.M.; Berretta, F.; de Souza, B.D.M.; Godolfim, L.R.; Demathe, T.; De Luca Canto, G.; Porporatti, A.L. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and alcohol, caffeine and tobacco: A meta-analysis. J. Oral Rehabil. 2018, 45, 890–902. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Jiang, S.; Hu, A. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2018, 22, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Guo, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Alcohol as an independent risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 191, 1325–1330. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J.; Lim, J.H.; Kim, D.B.; Joo, M.J.; Jang, Y.S.; Park, E.C.; Shin, J. Association between alcohol use disorder and risk of obstructive sleep apnea. J. Sleep Res. 2024, 33, e14128. [Google Scholar]

- Kolla, B.P.; Foroughi, M.; Saeidifard, F.; Chakravorty, S.; Wang, Z.; Mansukhani, M.P. The impact of alcohol on breathing parameters during sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018, 42, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simou, E.; Britton, J.; Leonardi-Bee, J. Alcohol and the risk of sleep apnoea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2018, 42, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppard, P.E.; Austin, D.; Brown, R.L. Association of alcohol consumption and sleep disordered breathing in men and women. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2007, 3, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, G.E.; Cho, E.J.; Yoo, J.J.; Chang, Y.; Cho, Y.; Park, S.H.; Shin, D.W.; Han, K.; Yu, S.J. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with the development of obstructive sleep apnea. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Choi, H.; Lee, J.; Kim, J. Obstructive sleep apnea and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population: A cross-sectional study using nationally representative data. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, X.; Chen, M.; Lin, T.; Chen, G. Association between metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea: A cross-sectional study. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Türkay, C.; Ozol, D.; Kasapoğlu, B.; Kirbas, I.; Yıldırım, Z.; Yiğitoğlu, R. Influence of obstructive sleep apnea on fatty liver disease: Role of chronic intermittent hypoxia. Respir. Care 2012, 57, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolow, G.K.; Garcia, E.; Schoor, F.; Araujo, F.B.S.; Coral, G.P. Obstructive sleep apnea and severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 33, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Umbro, I.; Fabiani, V.; Fabiani, M.; Angelico, F.; Del Ben, M. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 2669–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesarwi, O.A.; Loomba, R.; Malhotra, A. Obstructive sleep apnea, hypoxia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zheng, P.; Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Evidence, mechanism, and treatment. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2024, 16, 917–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron-Wisnewsky, J.; Clement, K.; Pépin, J.L. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and obstructive sleep apnea. Metabolism 2016, 65, 1124–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, M.A.; Alabdulathim, S.; Alhejaili, S.A.M.; Al Sheif, Z.A.A.; Aldossari, K.K.; Bakhsh, J.I.; Alharbi, F.M.; Ahmad, A.A.Y.; Aloufi, R.M.; Mushaeb, H. The association between obesity and the development and severity of obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review. Cureus 2024, 16, e69962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, Z. Association between obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and type1/type2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Diabetes Investig. 2025, 16, 521–534. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Huang, X.; Wang, H.; Bai, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in whole spectrum chronic kidney disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 526–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.F.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Sun, X.; Su, C.Y.; Zhang, L.Q. Association between obstructive sleep apnea severity and depression risk: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2024, 28, 2175–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Ren, Y.; Wu, K.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, N. Association between smoking behavior and ostructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2023, 25, 364–371. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S.R.; Seol, H.; Abbas, Z.; Lee, S.W. Exploring the role of artificial intelligence in smart healthcare: A capability and function-oriented review. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, D.; Cha, H.R.; Chung, S.W.; Choi, J.; Lee, D.; Shim, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Lim, Y.S.; Lee, H.C.; Lee, S.W.; et al. Association between statin use and the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: A nationwide cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 65, 102300. [Google Scholar]

| NAFLD (n, %) | AFLD (n, %) | p-Value | Std Diff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 896,302) | (n = 12,694) | |||

| Age at index (mean ± SD) | 51.3 ± 16.0 | 52.0 ± 13.0 | <0.0001 | 0.0457 |

| Female | 481,679 (53.7%) | 3743 (29.5%) | <0.0001 | 0.5077 |

| Male | 414,623 (46.3%) | 8951 (70.5%) | <0.0001 | 0.5077 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Depressive episode | 113,141 (12.6%) | 1620 (12.8%) | 0.6400 | 0.0042 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 175,000 (19.5%) | 1349 (10.6%) | <0.0001 | 0.2506 |

| Overweight and obesity | 165,746 (18.5%) | 750 (5.9%) | <0.0001 | 0.3918 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 39,062 (4.4%) | 456 (3.6%) | <0.0001 | 0.0392 |

| NAFLD (n, %) | AFLD (n, %) | p-Value | Std Diff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 11,583) | (n = 11,583) | |||

| Age at index (mean ± SD) | 51.9 ± 13.0 | 51.9 ± 13.0 | 0.9972 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 3499 (30.2%) | 3499 (30.2%) | 1.0000 | <0.0001 |

| Male | 8084 (69.8%) | 8084 (69.8%) | 1.0000 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Depressive episode | 1530 (13.2%) | 1531 (13.2%) | 0.9845 | 0.0003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1189 (10.3%) | 1188 (10.3%) | 0.9827 | 0.0003 |

| Overweight and obesity | 732 (6.3%) | 733 (6.3%) | 0.9785 | 0.0004 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 434 (3.7%) | 434 (3.7%) | 1.0000 | <0.0001 |

| Patients with OSA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD (Risk) (n = 896,302) | AFLD (Risk) (n = 12,694) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value for Proportionality | |

| 1-year | 2183 (0.244%) | 17 (0.134%) | 1.819 (1.129, 2.930) | 1.821 (1.129, 2.935) | 1.630 (1.011, 2.627) | 0.2165 |

| 2-year | 6531 (0.729%) | 40 (0.315%) | 2.312 (1.695, 3.154) | 2.322 (1.701, 3.170) | 2.022 (1.482, 2.759) | 0.8089 |

| 3-year | 12,643 (1.411%) | 66 (0.520%) | 2.713 (2.131, 3.453) | 2.738 (2.148, 3.489) | 2.318 (1.820, 2.953) | 0.9652 |

| 5-year | 27,244 (3.040%) | 152 (1.197%) | 2.538 (2.166, 2.974) | 2.587 (2.203, 3.037) | 2.086 (1.778, 2.446) | 0.3062 |

| Till 28 September 2025 | 51,673 (5.767%) | 292 (2.300%) | 2.506 (2.237, 2.808) | 2.598 (2.313, 2.919) | 2.062 (1.838, 2.313) | 0.2409 |

| Patients with OSA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAFLD (Risk) (n = 11,583) | AFLD (Risk) (n = 11,583) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value for Proportionality | |

| 1-year | 24 (0.207%) | 17 (0.147%) | 1.412 (0.759, 2.626) | 1.413 (0.759, 2.631) | 1.289 (0.693, 2.400) | 0.7202 |

| 2-year | 79 (0.682%) | 40 (0.345%) | 1.975 (1.351, 2.887) | 1.982 (1.354, 2.901) | 1.764 (1.206, 2.580) | 0.5512 |

| 3-year | 157 (1.355%) | 66 (0.570%) | 2.369 (1.786, 3.168) | 2.398 (1.796, 3.200) | 2.078 (1.559, 2.770) | 0.5847 |

| 5-year | 349 (3.013%) | 150 (1.295%) | 2.327 (1.925, 2.812) | 2.368 (1.952, 2.872) | 1.950 (1.610, 2.361) | 0.6414 |

| Till 28 September 2025 | 668 (5.767%) | 290 (2.504%) | 2.303 (2.012, 2.637) | 2.383 (2.071, 2.742) | 1.940 (1.690, 2.227) | 0.7488 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, L.-H.; Lin, H.-C.; Hsieh, W.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y. Differential Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alcoholic Versus Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122146

Chang L-H, Lin H-C, Hsieh W-C, Hsu C-Y. Differential Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alcoholic Versus Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122146

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Ling-Hui, Hui-Cheng Lin, Wen-Che Hsieh, and Chao-Yu Hsu. 2025. "Differential Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alcoholic Versus Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122146

APA StyleChang, L.-H., Lin, H.-C., Hsieh, W.-C., & Hsu, C.-Y. (2025). Differential Risk of Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Alcoholic Versus Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Propensity-Matched Cohort Study. Medicina, 61(12), 2146. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122146