Intraoperative Management of Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula in Cholesteatoma Surgery: Retrospective Case Series and Audiovestibular Follow-Up

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Chronic Otitis Media and Cholesteatoma

1.2. Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula: Incidence and Pathophysiology

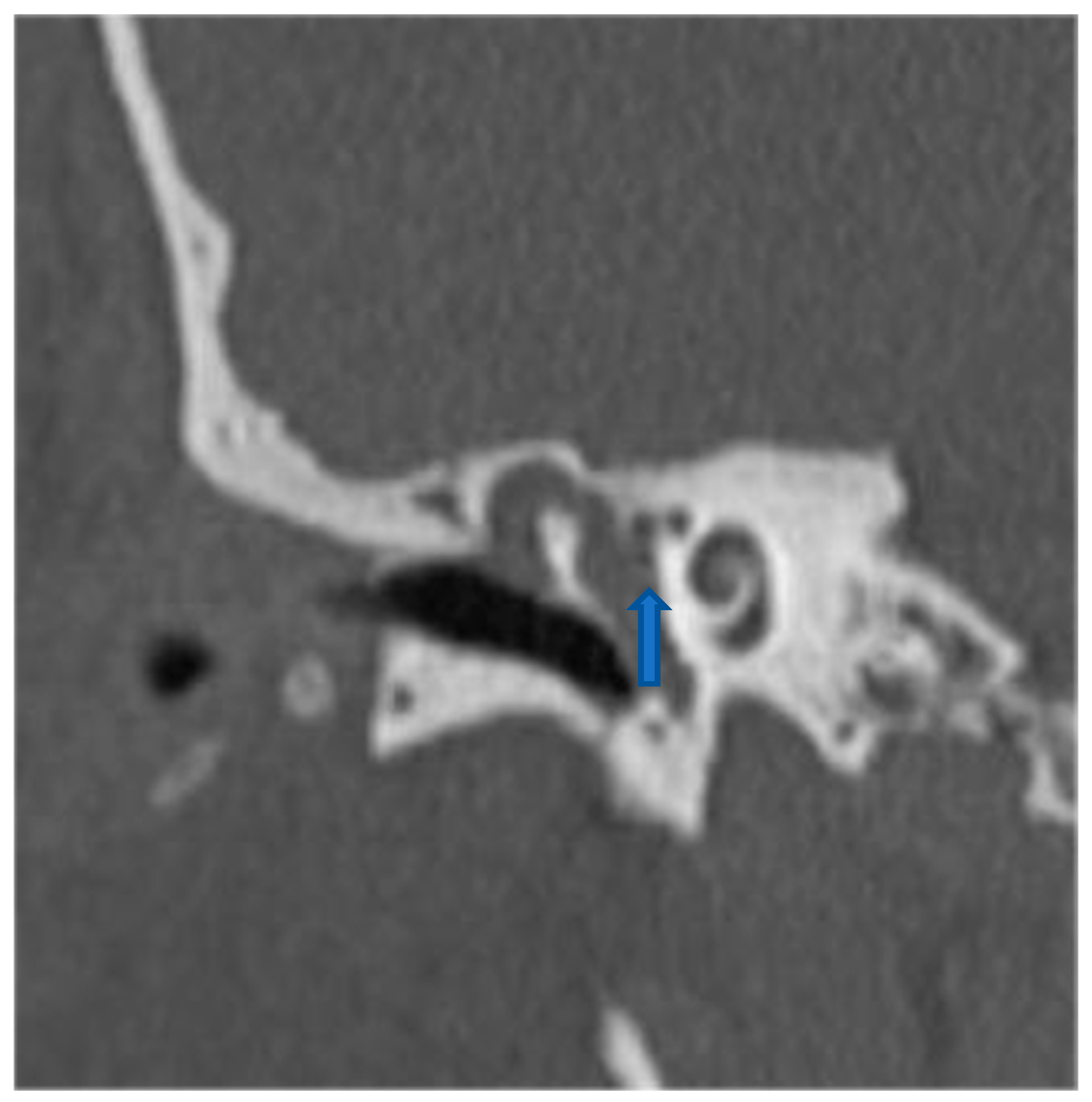

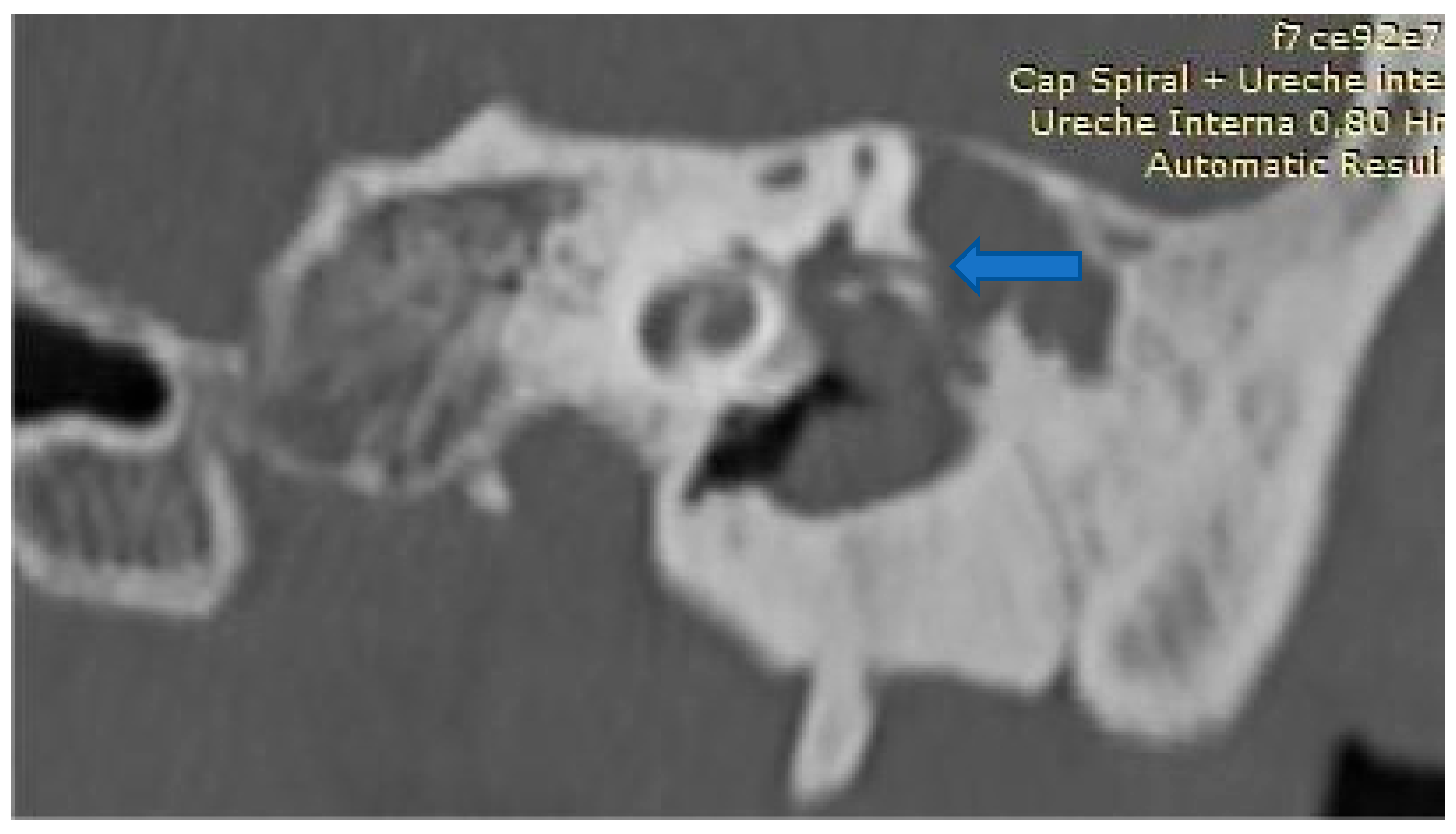

1.3. Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Workup

1.4. Surgical Management—A Therapeutic Dilemma

1.5. Surgical Innovations: “Underwater” and “Sandwich” Techniques

1.6. Evidence from the Literature: The Surgical Management of Semicircular Canal Fistulas

1.7. The Aim of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Study Cohort and Data Management

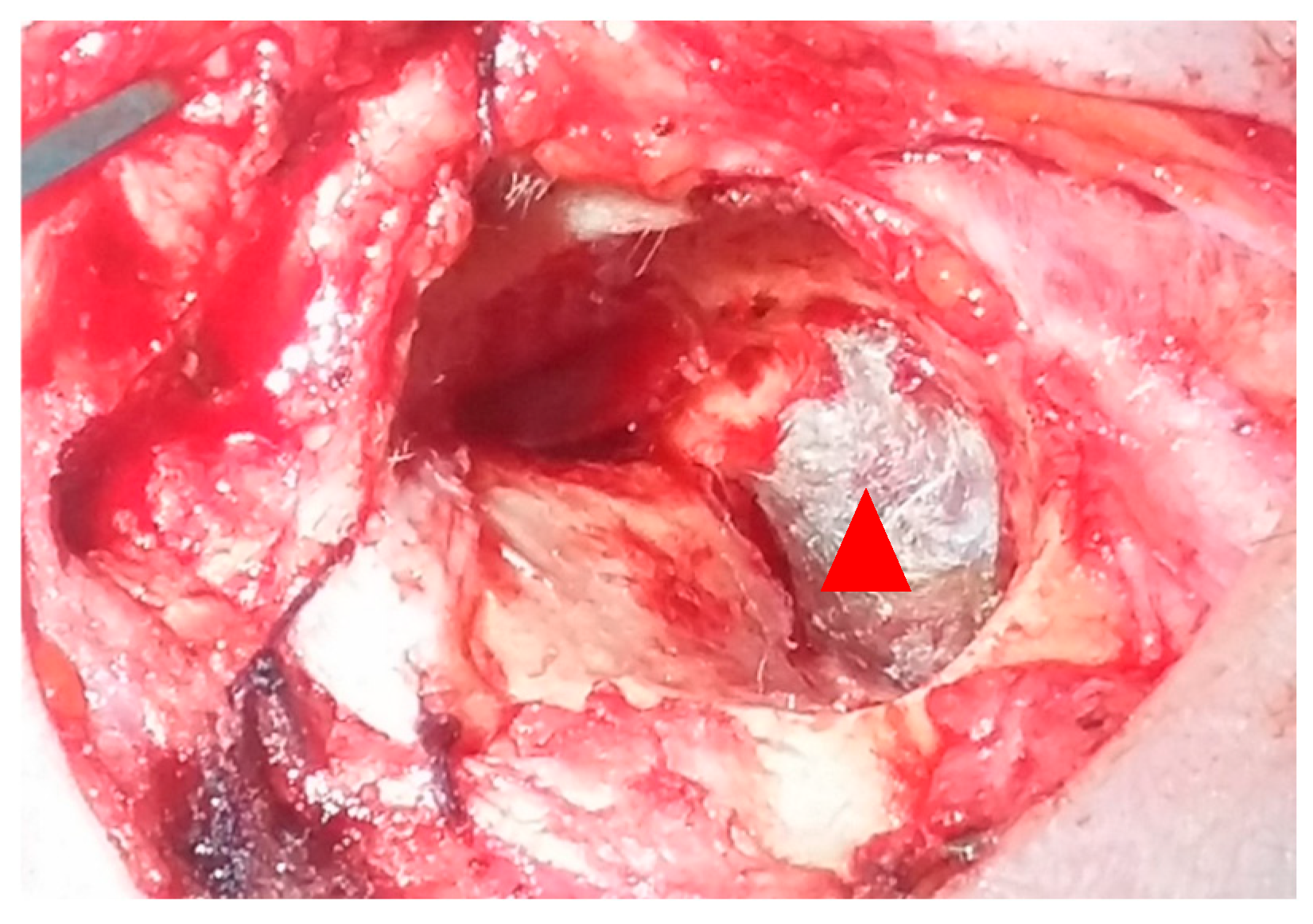

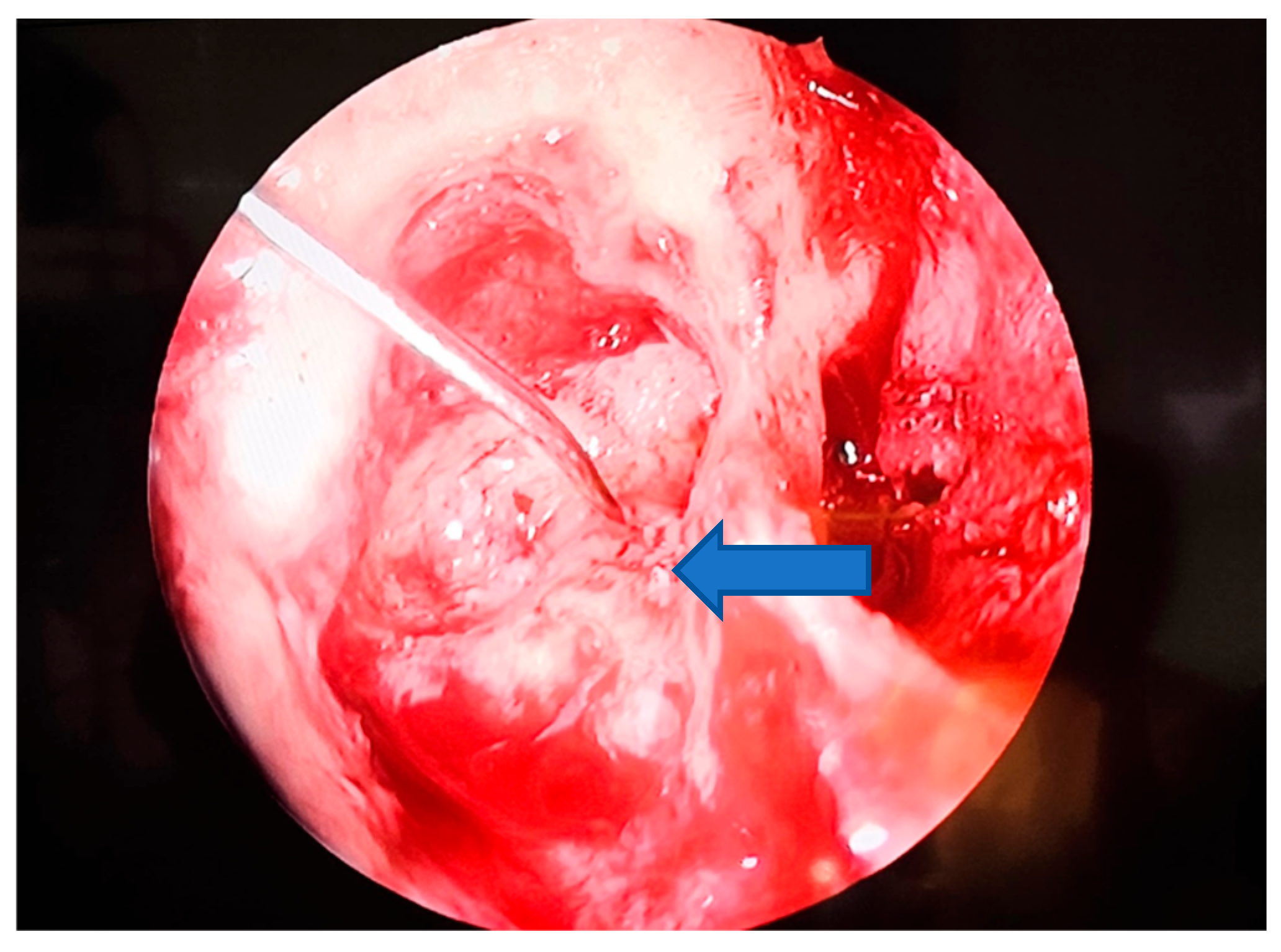

2.5. Surgical Methods

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Characteristics

3.2. Intraoperative Findings

3.3. Audiological Outcomes

3.4. Vestibular Outcomes

3.5. Complications

4. Discussion

4.1. Audiological Outcomes

4.2. Vestibular Outcomes

4.3. Technical Considerations

4.4. Study Limitations

4.5. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rosito, L.P.S.; Canali, I.; Teixeira, A.; Silva, M.N.; Selaimen, F.; Costa, S.S.D. Cholesteatoma labyrinthine fistula: Prevalence and impact. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 85, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gomaa, M.A.; Abdel Karim, A.R.; Abdel Ghany, H.S.; Elhiny, A.A.; Sadek, A.A. Evaluation of temporal bone cholesteatoma and the correlation between high resolution computed tomography and surgical finding. Clin. Med. Insights Ear Nose Throat 2013, 6, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gacek, R.R. The surgical management of labyrinthine fistulae in chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 1974, 83 (Suppl. 10), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, B.J.; Buchman, C.A. Management of labyrinthine fistulae in chronic ear surgery. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2003, 24, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiatr, M.; Składzien, J.; Wiatr, A.; Tomik, J.; Strêk, P.; Medoń, D. Postoperative bone conduction threshold changes in patients operated on for chronic otitis media–analysis. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2015, 69, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yamauchi, D.; Yamazaki, M.; Ohta, J.; Kadowaki, S.; Nomura, K.; Hidaka, H.; Oshima, T.; Kawase, T.; Katori, Y. Closure technique for labyrinthine fistula by “underwater” endoscopic ear surgery. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 2616–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.; Sousa, F.; Azevedo, S.; Lino, J.; Abrunhosa, J.; Meireles, L. Labyrinthine Fistula in Chronic Otitis Media Surgery: Management and Outcomes. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75 (Suppl. 1), 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aw, N.M.Y.; Thong, J.F.; Tan, B.Y.B.; Tan, V.Y.J. Managing cholesteatomas with labyrinthine fistula. Singap. Med. J. 2023; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartochowska, A.; Pietraszek, M.; Wierzbicka, M.; Gawęcki, W. “Sandwich technique” enables preservation of hearing and antivertiginous effect in cholesteatomatous labyrinthine fistula. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 279, 2329–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thangavelu, K.; Weiß, R.; Mueller-Mazzotta, J.; Schulze, M.; Stuck, B.A.; Reimann, K. Post-operative hearing among patients with labyrinthine fistula as a complication of cholesteatoma using “under water technique”. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2022, 279, 3355–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, R.; Delsing, C.P.A.; Saxby, A.; Kong, J.H.K.; Jufas, N.; Patel, N.P. Underwater endoscopic ear surgery for repair of lateral semicircular canal fistulae secondary to cholesteatoma—A pilot safety analysis. Aust. J. Otolaryngol. 2024, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Tian, K.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liang, K.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. A retrospective study on post-operative hearing of middle ear cholesteatoma patients with labyrinthine fistula. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016, 136, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornhoffer, J.L.; Milewski, C. Management of the open labyrinth. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1995, 112, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, F.X., Jr.; Zhang, L.; Ward, B.; Carey, J.P. Hearing outcomes for an underwater endoscopic technique for transmastoid repair of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Otol. Neurotol. 2021, 42, e1691–e1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djalilian, H.; Borrelli, M.; Desales, A. Cholesteatoma causing a horizontal semicircular canal fistula. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021, 100, 888s–891s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerse, S.; de Wolf, M.J.F.; Ebbens, F.A.; van Spronsen, E. Management of labyrinthine fistula: Hearing preservation versus prevention of residual disease. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 3605–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassannia, F.; Douglas-Jones, P.; Rutka, J.A. Gauging the effectiveness of canal occlusion surgery: How I do it. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2019, 133, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A.; Bouchetemblé, P.; Costentin, B.; Dehesdin, D.; Lerosey, Y.; Marie, J.P. Lateral semicircular canal fistula in cholesteatoma: Diagnosis and management. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 2055–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Xu, M.; Yao, Q.; Li, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Yu, D.; Shi, H.; Yin, S. Changes of vestibular symptoms in menière’s disease after triple semicircular canal occlusion: A long-term follow-up study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 797699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Yamauchi, D.; Kobayashi, T.; Ikeda, R.; Kawase, T.; Katori, Y. Hearing outcomes of transmastoid plugging for superior canal dehiscence syndrome by underwater endoscopic surgery: With special reference to transient bone conduction increase in early postoperative period. Otol. Neurotol. 2022, 43, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontorinis, G.; Thachil, G. Triple semicircular canal occlusion: A surgical perspective with short- and long-term outcomes. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2022, 136, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, P.; Gleich, O.; Spruss, T.; Strutz, J. Different materials for plugging a dehiscent superior semicircular canal: A comparative histologic study using a gerbil model. Otol. Neurotol. 2019, 40, e532–e541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Gangal, A.; Gluth, M.B. Surgery for cholesteatomatous labyrinthine fistula. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2017, 126, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulec, A.A.; Poe, D.S.; McKenna, M.J. Operative management of superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misale, P.; Lepcha, A.; Chandrasekharan, R.; Manusrut, M. Labyrinthine fistulae in squamosal type of chronic otitis media: Therapeutic outcome. Iran. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 31, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Lagman, C.; Sheppard, J.P.; Romiyo, P.; Duong, C.; Prashant, G.N.; Gopen, Q.; Yang, I. Middle cranial fossa approach for the repair of superior semicircular canal dehiscence is associated with greater symptom resolution compared to transmastoid approach. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 1219–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossen, M.E.; Stokroos, R.; Kingma, H.; van Tongeren, J.; Van Rompaey, V.; Temel, Y.; van de Berg, R. Heterogeneity in reported outcome measures after surgery in superior canal dehiscence syndrome-a systematic literature review. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, N.; Liuzzi, C.; Zizzi, S.; Dicorato, A.; Quaranta, A. Surgical treatment of labyrinthine fistula in cholesteatoma surgery. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2009, 140, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rah, Y.C.; Han, W.G.; Joo, J.W.; Nam, K.J.; Rhee, J.; Song, J.J.; Im, G.J.; Chae, S.W.; Jung, H.H.; Choi, J. One-stage complete resection of cholesteatoma with labyrinthine fistula: Hearing changes and clinical outcomes. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2018, 127, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committeri, U.; Monarchi, G.; Gilli, M.; Caso, A.R.; Sacchi, F.; Abbate, V.; Troise, S.; Consorti, G.; Giovacchini, F.; Mitro, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in the Surgery-First Approach: Harnessing Deep Learning for Enhanced Condylar Reshaping Analysis: A Retrospective Study. Life 2025, 15, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stultiens, J.J.A.; Guinand, N.; Van Rompaey, V.; érez Fornos, A.P.; Kunst, H.P.M.; Kingma, H.; van de Berg, R. The resilience of the inner ear-vestibular and audiometric impact of transmastoid semicircular canal plugging. J. Neurol. 2022, 269, 5229–5238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziylan, F.; Kinaci, A.; Beynon, A.J.; Kunst, H.P. A comparison of surgical treatments for superior semicircular canal dehiscence: A systematic review. Otol. Neurotol. 2017, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Study (Author, Year) | Patients (n) | Fistula Types (Dornhoffer) | Fistula Location | Surgical Technique | Reconstruction Material | Audiological Outcomes | Vestibular Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosito et al., 2019 (Braz J. Otorhinolaryngol.) [1] | 9 patients with fistula (2.7% of 333 cholesteatomas), all LSCC | 7 × Type II, 1 × Type III | Lateral (100%) | Mastoidectomy; matrix removed in Type II, matrix preserved in Type III; defect repaired in same stage | Autologous temporalis fascia + bone pâté, layered | BC thresholds preserved in ~80%; 1 patient (Type III, matrix preserved) progressed to profound deafness | Not reported |

| Castro et al., 2023 (Indian J. OHNS) [7] | 26 patients with fistula (9.9% of 263 cholesteatomas), all LSCC | 10 × Type I, 15 × Type II, 1 × Type III | Lateral (100%) | CWU or CWD mastoidectomy, tailored; matrix removed in 25/26 cases | Autologous fascia and/or bone pâté | BC preserved or improved in 73%; no significant link between fistula grade/material and HL | Not reported |

| Aw et al., 2023 (Singapore Med. J.) [8] | 14 ears in 13 patients (15.6% of cholesteatomas), mostly LSCC | Not specified (≥Type II; 2 large fistulas with matrix left in situ) | Predominantly lateral | CWD mastoidectomy for all; matrix removed in 12/14, preserved in 2 with large fistulas and good preop hearing | Autologous fascia ± bone pâté | 78% stable BC, 11% improved, 11% worsened after matrix removal; hearing worsened in matrix-preserved cases | Not reported |

| Bartochowska et al., 2022 (Eur. Arch. ORL) [9] | 38 patients (from 53 fistulas, 87% LSCC) | 4 × Type I, ~19 × Type IIa, ~9 × Type IIb, 6 × Type III | Predominantly lateral (LSCC 87%) | CWU or CWD depending on disease; better results with CWU; complete matrix removal in all | Autologous fascia + bone pâté, “sandwich technique” for Type II–III | Hearing preserved/improved in 79%; protective factors: CWU, intact membranous labyrinth, sandwich technique | Postop vertigo significantly less frequent with sandwich technique; episodes transient (3–30 days) |

| Thangavelu et al., 2022 (Eur. Arch. ORL) [10] | 20 patients (4.4% incidence) | 5 × Type I, 7 × Type II, 10 × Type III | Mostly lateral: 15 LSCC, 2 SSCC, 1 combined LSCC+SSCC | CWD mastoidectomy; complete matrix removal with underwater technique (continuous irrigation, no suction) | Autologous fascia, bone pâté, fibrin glue | No new SNHL; 20% improved BC > 10 dB, 80% unchanged; 2 dead ears remained unchanged | Preop vertigo in 35%; only 10% postop, both transient; no new or persistent vestibular deficits |

| Chen et al., 2024 (Aust. J. Otolaryngol.) [11] | 11 patients, all LSCC | 5 × Type IIa, 5 × Type IIb, 1 × Type III | Lateral (100%) | Underwater Endoscopic Ear Surgery (UWEES), transcanal approach | Fascia, bone pâté, cartilage composite | Hearing preserved in 10/11; no significant BC change; only 1 patient (Type III) developed significant SNHL | Vertigo resolved in 82%; only 1 patient (11%) had mild residual vertigo at 6 months |

| Yue et al., 2016 (Acta Otolaryngol.) [12] | 35 patients (25 LSCC, 4 PSCC, 2 SSCC, 4 multiple) | Not classified; 4 cases with vestibule/cochlea involvement (likely Type III) | 71% LSCC; 6% SSCC; 11% PSCC | Radical or CWD mastoidectomy; complete matrix removal in all | Fascia temporalis | No postoperative BC deterioration; complete matrix removal considered safe for hearing | Not reported |

| Case Number | Gender | Affected Ear | Affected Semicircular Canal | Fistula Grading | Surgical Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | m | Left ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type I | CWD |

| 2 | m | Right ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type II | CWD |

| 3 | m | Left ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type III | CWD |

| 4 | f | Right ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type IIb | CWD |

| 5 | f | Left ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type IIa | CWD |

| 6 | f | Right ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type IIb | CWD |

| 7 | f | Left ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type II | CWD |

| 8 | f | Right ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type I | CWU |

| 9 | f | Left ear | LSCF | Dornhoffer Type IIa | CWD |

| Domain | Assessment Method |

|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation | Otoscopy and otomicroscopy—tympanic membrane status, extent of cholesteatoma |

| Audiological tests | Pure-tone audiometry (0.5, 1, 2, 4 kHz); air–bone gap (ABG) calculation |

| Vestibular tests | Bedside clinical evaluation including Head Impulse, Nystagmus, and Test of Skew (HINTS) |

| Imaging | High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of temporal bone for disease extent, ossicular erosion, and fistula localization |

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Surgical approach |

|

| Fistula classification (Dornhoffer and Milewski) |

|

| Matrix removal | Gentle dissection under continuous irrigation with cottonoids soaked in dexamethasone and adrenaline; suction/traction strictly avoided |

| Closure materials | Temporalis fascia, temporalis muscle, gelfoam, or combinations thereof |

| Repair techniques |

|

| Intraoperative monitoring | Continuous facial nerve monitoring |

| Domain | Protocol |

|---|---|

| Medical therapy | Intravenous antibiotics, corticosteroids, vestibular suppressants |

| Audiological follow-up | Bedside audiometry on day 1, repeated at 6 and 12 months |

| Vestibular follow-up | HINTS evaluation immediately postoperative and during follow-up visits |

| Rehabilitation | Vestibular rehabilitation if imbalance >2 weeks; betahistine (24 mg BID) in selected cases |

| Long-term follow-up | Minimum 12 months with serial audiological and vestibular assessments |

| Variable | All Mastoidectomy Patients (n = 1861) | Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula Subgroup (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male: ~55% Female: ~45 | Male: 3 (33%) Female: 6 (67%) |

| Age (years) | Mean: ~50–55 years | Mean: 65.8 ± 13.6 (range: 40–82) |

| Type of mastoidectomy | CWD: 68% CWU: 22% Other: 10% (based on institutional data) | CWD: 8 (89%) CWU: 1 (11%) |

| Labyrinthine fistula incidence | 9 (0.5%) of cohort | — |

| Complications | Facial nerve dehiscence: 5 (56%) Tegmen tympani dehiscence: 1 (11%) Meningitis: 1 (11%) | |

| Audiological outcomes | Improved: 3 (33%) Stable: 4 (44%) Worsened: 2 (22%) | |

| Vestibular outcomes | Immediate resolution: 7 (78%) Delayed resolution (≤3 months): 2 (22%) Persistent deficit: 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zica, M.D.; Voiosu, C.; Rusescu, A.; Ionita, I.; Gherasie, L.M.; Alius, O.R.; Bizdu Branovici, A.; Hainarosie, R.; Zainea, V. Intraoperative Management of Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula in Cholesteatoma Surgery: Retrospective Case Series and Audiovestibular Follow-Up. Medicina 2025, 61, 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122144

Zica MD, Voiosu C, Rusescu A, Ionita I, Gherasie LM, Alius OR, Bizdu Branovici A, Hainarosie R, Zainea V. Intraoperative Management of Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula in Cholesteatoma Surgery: Retrospective Case Series and Audiovestibular Follow-Up. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122144

Chicago/Turabian StyleZica, Maria Denisa, Catalina Voiosu, Andreea Rusescu, Irina Ionita, Luana Maria Gherasie, Oana Ruxandra Alius, Alexandra Bizdu Branovici, Razvan Hainarosie, and Viorel Zainea. 2025. "Intraoperative Management of Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula in Cholesteatoma Surgery: Retrospective Case Series and Audiovestibular Follow-Up" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122144

APA StyleZica, M. D., Voiosu, C., Rusescu, A., Ionita, I., Gherasie, L. M., Alius, O. R., Bizdu Branovici, A., Hainarosie, R., & Zainea, V. (2025). Intraoperative Management of Lateral Semicircular Canal Fistula in Cholesteatoma Surgery: Retrospective Case Series and Audiovestibular Follow-Up. Medicina, 61(12), 2144. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122144