Hyperleptinemia Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Vascular Reactivity Impairment in Patients with Hypertension

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Anthropometric Analysis and Biochemical Determinations

2.3. Endothelial Function Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Areas under the curve |

| BCa | Bias-corrected and accelerated |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| BUN | Blood urea nitrogen |

| CAD | Coronary artery disease |

| CVD | Cardiovascular disease |

| DBP | Diastolic blood pressure |

| DM | Diabetes mellitus |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| eNOS | Endothelial nitric oxide synthase |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| SBP | Systolic blood pressure |

| TCH | Total cholesterol |

| VRI | Vascular reactivity index |

References

- Wu, X.; Sha, J.; Yin, Q.; Gu, Y.; He, X. Global burden of hypertensive heart disease and attributable risk factors, 1990–2021: Insights from the global burden of disease study 2021. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, F.D.; Whelton, P.K. High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2020, 75, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Volpe, M.; Savoia, C. Endothelial dysfunction in hypertension: Current concepts and clinical implications. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 798958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konukoglu, D.; Uzun, H. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 511–540. [Google Scholar]

- Morioka, T.; Emoto, M.; Yamazaki, Y.; Kawano, N.; Imamura, S.; Numaguchi, R.; Urata, H.; Motoyama, K.; Mori, K.; Fukumoto, S.; et al. Leptin is associated with vascular endothelial function in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2014, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahima, R.S.; Flier, J.S. Leptin. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2000, 62, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltowski, J. Leptin and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2006, 189, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, L.; Hesong, Z. Role of leptin in atherogenesis. Exp. Clin. Cardiol. 2006, 11, 269–275. [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg, S.; Ahrén, B.; Jansson, J.H.; Johnson, O.; Hallmans, G.; Asplund, K.; Olsson, T. Leptin is associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction. J. Intern. Med. 1999, 246, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A.M.; McMahon, A.D.; Packard, C.J.; Kelly, A.; Shepherd, J.; Gaw, A.; Sattar, N. Plasma leptin and the risk of cardiovascular disease in the west of Scotland coronary prevention study (WOSCOPS). Circulation 2001, 104, 3052–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adya, R.; Tan, B.K.; Randeva, H.S. Differential effects of leptin and adiponectin in endothelial angiogenesis. J. Diabetes Res. 2015, 2015, 648239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruder-Nascimento, T.; Faulkner, J.L.; Haigh, S.; Kennard, S.; Antonova, G.; Patel, V.S.; Fulton, D.J.R.; Chen, W.; Belin de Chantemèle, E.J. Leptin restores endothelial function via endothelial PPARγ-Nox1-mediated mechanisms in a mouse model of congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Hypertension 2019, 74, 1399–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, K.; Higashi, Y.; Sasaki, S.; Oshima, T.; Matsuura, H.; Chayama, K. Leptin causes vasodilation in humans. Hypertens. Res. 2002, 25, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Teragawa, H.; Fukuda, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Higashi, Y.; Chayama, K. Leptin causes nitric-oxide independent coronary artery vasodilation in humans. Hypertens. Res. 2003, 26, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembo, G.; Vecchione, C.; Fratta, L.; Marino, G.; Trimarco, V.; d’Amati, G.; Trimarco, B. Leptin induces direct vasodilation through distinct endothelial mechanisms. Diabetes 2000, 49, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korda, M.; Kubant, R.; Patton, S.; Malinski, T. Leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction in obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2008, 295, H1514–H1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knudson, J.D.; Dincer, U.D.; Zhang, C.; Swafford, A.N., Jr.; Koshida, R.; Picchi, A.; Focardi, M.; Dick, G.M.; Tune, J.D. Leptin receptors are expressed in coronary arteries, and hyperleptinemia causes significant coronary endothelial dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005, 289, H48–H56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundell, J.; Huupponen, R.; Raitakari, O.T.; Nuutila, P.; Knuuti, J. High serum leptin is associated with attenuated coronary vasoreactivity. Obes. Res. 2003, 11, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Lind, L.; Söderberg, S. Leptin and endothelial function in the elderly: The prospective investigation of the vasculature in Uppsala seniors (PIVUS) study. Atherosclerosis 2013, 228, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Liu, B.; Song, J.; Bao, S.; Zhen, J.; Lv, Z.; Wang, R. Leptin promotes endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease through AKT/GSK3β and β-catenin signals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016, 480, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.W.; Chi, P.J.; Lin, Y.L.; Wang, C.H.; Hsu, B.G. Serum leptin levels are positively associated with aortic stiffness in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3-5. Adipocyte 2020, 9, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Yen, A.A.; Lin, A.W.; Tanaka, H.; Kleis, S. New indices of endothelial function measured by digital thermal monitoring of vascular reactivity: Data from 6084 patients registry. Int. J. Vasc. Med. 2016, 2016, 1348028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, N.; McQuilkin, G.L.; Akhtar, M.W.; Hajsadeghi, F.; Kleis, S.J.; Hecht, H.; Naghavi, M.; Budoff, M. Reproducibility and variability of digital thermal monitoring of vascular reactivity. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2011, 31, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, M.; Gourley, D.; Naghavi, M.; Klies, S.; Tanaka, H. Digital thermal monitoring techniques to assess vascular reactivity following finger and brachial occlusions. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2020, 23, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seals, D.R.; Jablonski, K.L.; Donato, A.J. Aging and vascular endothelial function in humans. Clin. Sci. 2011, 120, 357–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Lin, Y.L.; Hsu, B.G. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic kidney disease: Mechanisms, biomarkers, diagnostics, and therapeutic strategies. Tzu Chi Med. J. 2025, 37, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitocco, D.; Tesauro, M.; Alessandro, R.; Ghirlanda, G.; Cardillo, C. Oxidative stress in diabetes: Implications for vascular and other complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21525–21550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinzari, F.; Tesauro, M.; Rovella, V.; Galli, A.; Mores, N.; Porzio, O.; Lauro, D.; Cardillo, C. Generalized impairment of vasodilator reactivity during hyperinsulinemia in patients with obesity-related metabolic syndrome. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 299, E947–E952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesauro, M.; Rizza, S.; Iantorno, M.; Campia, U.; Cardillo, C.; Lauro, D.; Leo, R.; Turriziani, M.; Cocciolillo, G.C.; Fusco, A.; et al. Vascular, metabolic, and inflammatory abnormalities in normoglycemic offspring of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 2007, 56, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, G.F. Arterial stiffness in aging: Does it have a place in clinical practice? Recent advances in hypertension. Hypertension 2021, 77, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellott, E.; Faulkner, J.L. Mechanisms of leptin-induced endothelial dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2023, 32, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Shen, X. Oxidative stress and adipokine levels were significantly correlated in diabetic patients with hyperglycemic crises. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2019, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessie, G.; Ayelign, B.; Akalu, Y.; Shibabaw, T.; Molla, M.D. Effect of leptin on chronic inflammatory disorders: Insights to therapeutic target to prevent further cardiovascular complication. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3307–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakrania, B.A.; Spradley, F.T.; Drummond, H.A.; LaMarca, B.; Ryan, M.J.; Granger, J.P. Preeclampsia: Linking placental ischemia with maternal endothelial and vascular dysfunction. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1315–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradovic, M.; Sudar-Milovanovic, E.; Soskic, S.; Essack, M.; Arya, S.; Stewart, A.J.; Gojobori, T.; Isenovic, E.R. Leptin and obesity: Role and clinical implication. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 585887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savova, M.S.; Mihaylova, L.V.; Tews, D.; Wabitsch, M.; Georgiev, M.I. Targeting PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in obesity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 159, 114244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, P.; Khanal, S. Leptin in atherosclerosis: Focus on macrophages, endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.N.; Rivera-Gonzalez, O.; Gibert, Y.; Speed, J.S. Endothelin-1 in the pathophysiology of obesity and insulin resistance. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A. Novel molecular aspects of ghrelin and leptin in the control of adipobiology and the cardiovascular system. Obes. Facts 2014, 7, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaszak-Jasiecka, A.; Płoska, A.; Wierońska, J.M.; Dobrucki, L.W.; Kalinowski, L. Endothelial dysfunction due to eNOS uncoupling: Molecular mechanisms as potential therapeutic targets. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2023, 28, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; do Carmo, J.M.; da Silva, A.A.; Wang, Z.; Hall, M.E. Obesity-induced hypertension: Interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Stornetta, R.L.; Stornetta, D.S.; Abbott, S.B.G.; Brooks, V.L. The arcuate nucleus: A site of synergism between angiotensin II and leptin to increase sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2022, 785, 136773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechanick, J.I.; Farkouh, M.E.; Newman, J.D.; Garvey, W.T. Cardiometabolic-based chronic disease, adiposity and dysglycemia drivers: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedewa, M.V.; Hathaway, E.D.; Ward-Ritacco, C.L.; Williams, T.D.; Dobbs, W.C. The effect of chronic exercise training on leptin: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 1437–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varady, K.A. Intermittent versus daily calorie restriction: Which diet regimen is more effective for weight loss? Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, e593–e601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Sohouli, M.H.; Rohani, P.; Fotros, D.; Velu, P.; Ziamanesh, F.; Fatahi, S.; Shojaie, S.; Li, Y. The effect of metformin on adipokines levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 207, 111076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iepsen, E.W.; Lundgren, J.; Dirksen, C.; Jensen, J.E.; Pedersen, O.; Hansen, T.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Torekov, S.S. Treatment with a GLP-1 receptor agonist diminishes the decrease in free plasma leptin during maintenance of weight loss. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | All Participants (n = 100) | Good Vascular Reactivity (n = 44) | Intermediate Vascular Reactivity (n = 46) | Poor Vascular Reactivity (n = 10) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.52 ± 8.26 | 61.61 ± 7.20 | 63.98 ± 8.79 | 66.79 ± 7.35 | 0.015 * |

| Height (cm) | 163.89 ± 7.40 | 162.30 ± 7.63 | 165.51 ± 7.44 | 163.50 ± 4.65 | 0.118 |

| Body weight (kg) | 73.39 ± 11.52 | 71.03 ± 9.35 | 76.27 ± 13.53 | 70.57 ± 6.98 | 0.069 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.27 ± 3.47 | 26.96 ± 3.05 | 27.76 ± 4.09 | 26.34 ± 1.44 | 0.373 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 86.82 ± 8.53 | 82.84 ± 6.62 | 89.02 ± 8.17 | 94.20 ± 9.76 | <0.001 * |

| Vascular reactivity index | 1.89 ± 0.62 | 2.42 ± 0.35 | 1.66 ± 0.21 | 0.62 ± 0.22 | <0.001 * |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 135.17 ± 18.66 | 136.68 ± 16.86 | 134.63 ± 20.14 | 131.00 ± 20.29 | 0.666 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 79.96 ± 11.05 | 81.55 ± 10.04 | 78.98 ± 12.00 | 77.50 ± 10.78 | 0.418 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 139.50 (141.00–178.00) | 160.00 (141.00–176.75) | 156.50 (135.75–187.50) | 172.00 (154.00–189.50) | 0.351 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 141.00 (104.50–206.00) | 136.00 (101.25–205.50) | 138.00 (110.00–204.00) | 174.00 (83.75–217.00) | 0.892 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 46.44 ± 10.29 | 47.57 ± 10.14 | 44.39 ± 10.03 | 50.90 ± 10.95 | 0.120 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | 87.00 (71.00–106.00) | 87.00 (70.25–97.00) | 85.50 (69.75–112.25) | 96.00 (79.50–113.25) | 0.446 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dL) | 112.00 (92.25–152.25) | 115.00 (95.50–153.75) | 112.00 (92.75–155.75) | 98.50 (87.25–136.75) | 0.297 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.37 ± 0.23 | 4.41 ± 0.25 | 4.34 ± 0.19 | 4.30 ± 0.31 | 0.239 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 17.00 (14.00–20.00) | 16.50 (13.00–19.00) | 17.00 (14.00–22.25) | 18.50 (13.75–23.50) | 0.164 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.00 (0.83–1.10) | 0.90 (0.80–1.10) | 1.00 (0.90–1.13) | 1.00 (0.90–1.10) | 0.160 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 80.76 ± 22.44 | 86.27 ± 23.71 | 77.34 ± 20.13 | 72.21 ± 23.20 | 0.074 |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 27.82 ± 10.65 | 23.02 ± 8.08 | 30.36 ± 10.75 | 37.27 ± 10.60 | <0.001 * |

| Male, n (%) | 82 (82.0) | 35 (79.5) | 40 (87.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0.383 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 48 (48.0) | 23 (52.3) | 18 (39.1) | 7 (70.0) | 0.156 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 72 (72.0) | 32 (72.7) | 34 (73.9) | 6 (60.0) | 0.667 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 19 (19.0) | 12 (27.3) | 5 (10.9) | 2 (20.0) | 0.140 |

| ACE inhibitor use, n (%) | 20 (20.0) | 9 (20.5) | 10 (21.7) | 1 (10.0) | 0.669 |

| ARB use, n (%) | 51 (51.0) | 24 (54.5) | 21 (45.7) | 6 (60.0) | 0.585 |

| β-blocker use, n (%) | 43 (43.0) | 17 (38.6) | 21 (45.7) | 5 (50.0) | 0.714 |

| CCB use, n (%) | 45 (45.0) | 21 (47.7) | 21 (45.7) | 3 (30.0) | 0.592 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 74 (74.0) | 31 (70.5) | 36 (78.3) | 7 (70.0) | 0.669 |

| Fibrate use, n (%) | 7 (7.0) | 4 (9.1) | 2 (4.3) | 1 (10.0) | 0.628 |

| Model | Leptin (per 1 ng/mL of Increase) for Vascular Reactivity Dysfunction | Leptin (per 1 ng/mL of Increase) for Poor Vascular Reactivity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Crude model | 1.098 (1.045–1.153) | <0.001 * | 1.092 (1.025–1.162) | 0.006 * |

| Adjusted model | 1.096 (1.025–1.171) | 0.007 * | 1.197 (1.034–1.387) | 0.016 * |

| Variables | Vascular Reactivity Index | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Regression | Multivariable Regression | ||||

| r | p Value | Beta | Adjusted R2 Change | p Value | |

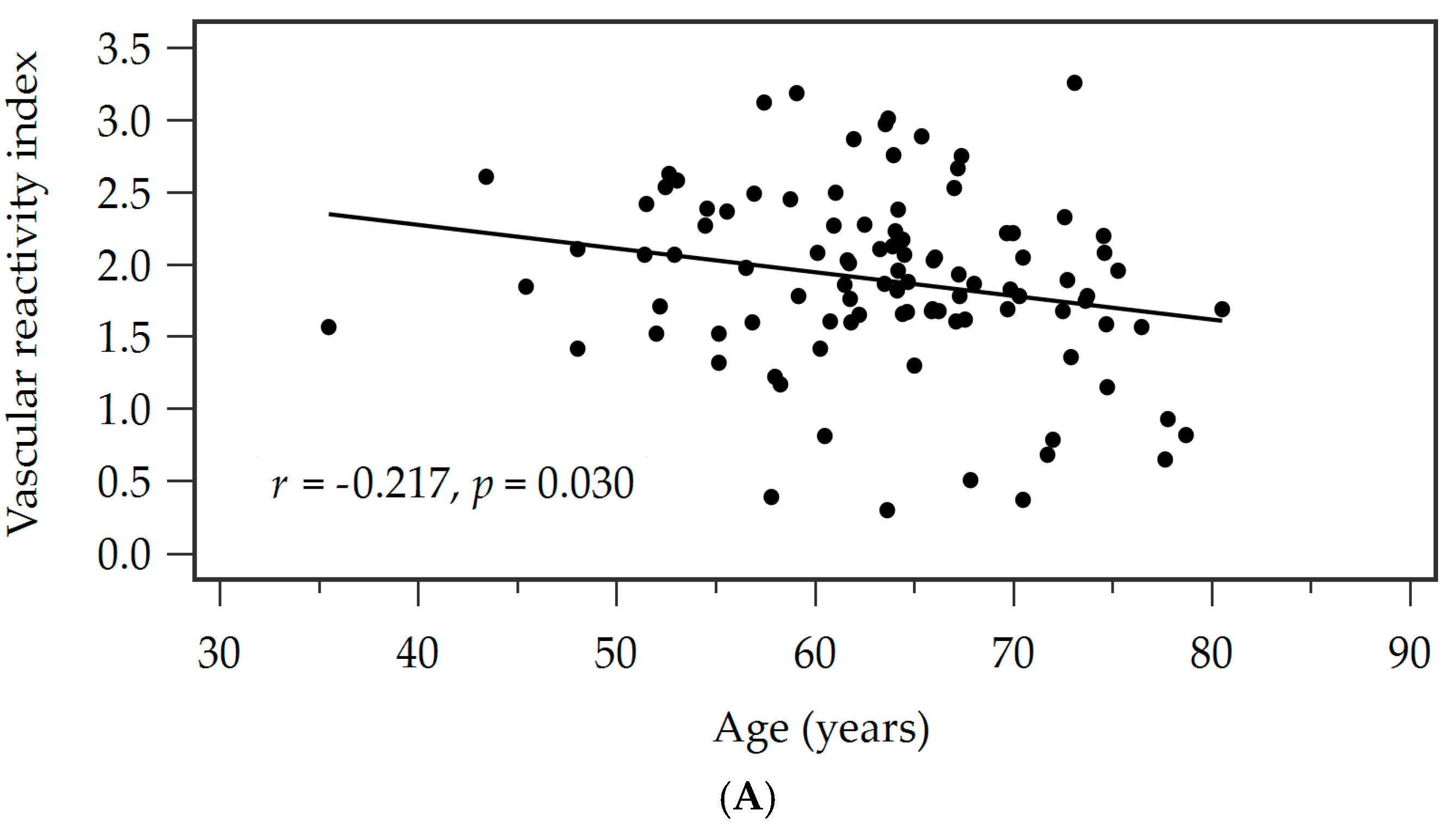

| Age (years) | −0.217 | 0.030 * | −0.178 | 0.025 | 0.036 * |

| Height (cm) | −0.069 | 0.494 | – | – | – |

| Body weight (kg) | −0.095 | 0.345 | – | – | – |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | −0.061 | 0.544 | – | – | – |

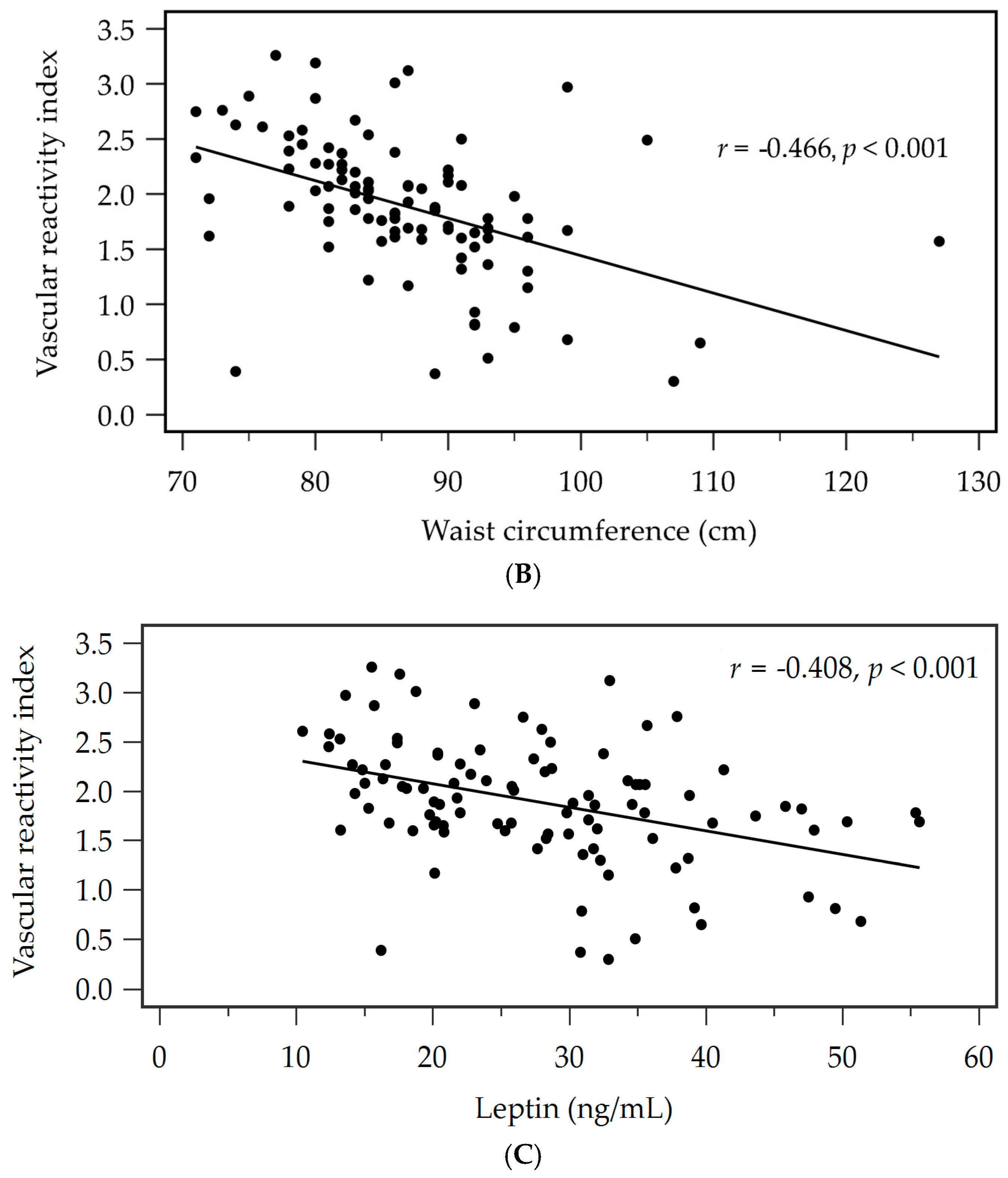

| Waist circumference (cm) | −0.466 | <0.001 * | −0.413 | 0.209 | <0.001 * |

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.089 | 0.379 | – | – | – |

| DBP (mmHg) | 0.123 | 0.222 | – | – | – |

| Log-TCH (mg/dL) | −0.163 | 0.104 | – | – | – |

| Log-Triglyceride (mg/dL) | −0.044 | 0.663 | – | – | – |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | −0.019 | 0.847 | – | – | – |

| Log-LDL-C (mg/dL) | −0.112 | 0.268 | – | – | – |

| Log-Glucose (mg/dL) | 0.143 | 0.157 | – | – | – |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 0.167 | 0.096 | – | – | – |

| Log-BUN (mg/dL) | −0.169 | 0.092 | – | – | – |

| Log-Creatinine (mg/dL) | −0.124 | 0.220 | – | – | – |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 0.153 | 0.129 | – | – | – |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | −0.408 | <0.001 * | −0.296 | 0.098 | 0.001 * |

| Vascular Reactivity Dysfunction | |||||||

| AUC (95% CI) | p Value | Cut-Off | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 0.724 (0.625–0.824) | <0.001 * | 28.70 | 60.71 | 79.55 | 79.07 | 61.40 |

| Poor Vascular Reactivity | |||||||

| AUC (95% CI) | p Value | Cut-Off | Sen (%) | Spe (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | |

| Leptin (ng/mL) | 0.770 (0.606–0.932) | 0.0012 * | 30.25 | 90.0 | 65.56 | 22.50 | 98.33 |

| Variables | B | BCa 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leptin, ng/mL | 0.092 | 0.009, 0.361 | 0.004 |

| Waist circumference, cm | 0.147 | 0.027, 0.825 | <0.001 |

| Age, year | 0.099 | −0.014, 0.456 | 0.027 |

| Diabetes, present | −0.349 | −0.2.165, 1.047 | 0.591 |

| Smoking, present | −0.863 | −2.804, 0.516 | 0.237 |

| Height, cm | 0.097 | −0.060, 0.439 | 0.058 |

| Body weight, kg | 0.018 | −0.076, 0.141 | 0.581 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL | −0.024 | −0.112, 0.039 | 0.445 |

| eGFR, mL/min | −0.009 | −0.062, 0.026 | 0.594 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, I.-M.; Chuang, L.-L.; Wang, J.-H.; Hsu, B.-G. Hyperleptinemia Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Vascular Reactivity Impairment in Patients with Hypertension. Medicina 2025, 61, 2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122132

Su I-M, Chuang L-L, Wang J-H, Hsu B-G. Hyperleptinemia Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Vascular Reactivity Impairment in Patients with Hypertension. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122132

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, I-Min, Li-Liang Chuang, Ji-Hung Wang, and Bang-Gee Hsu. 2025. "Hyperleptinemia Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Vascular Reactivity Impairment in Patients with Hypertension" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122132

APA StyleSu, I.-M., Chuang, L.-L., Wang, J.-H., & Hsu, B.-G. (2025). Hyperleptinemia Is a Risk Factor for the Development of Vascular Reactivity Impairment in Patients with Hypertension. Medicina, 61(12), 2132. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122132