The Dermatology Fast Track as a Model for Integrated Care Pathways Between Emergency Medicine and Outpatient Specialty Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

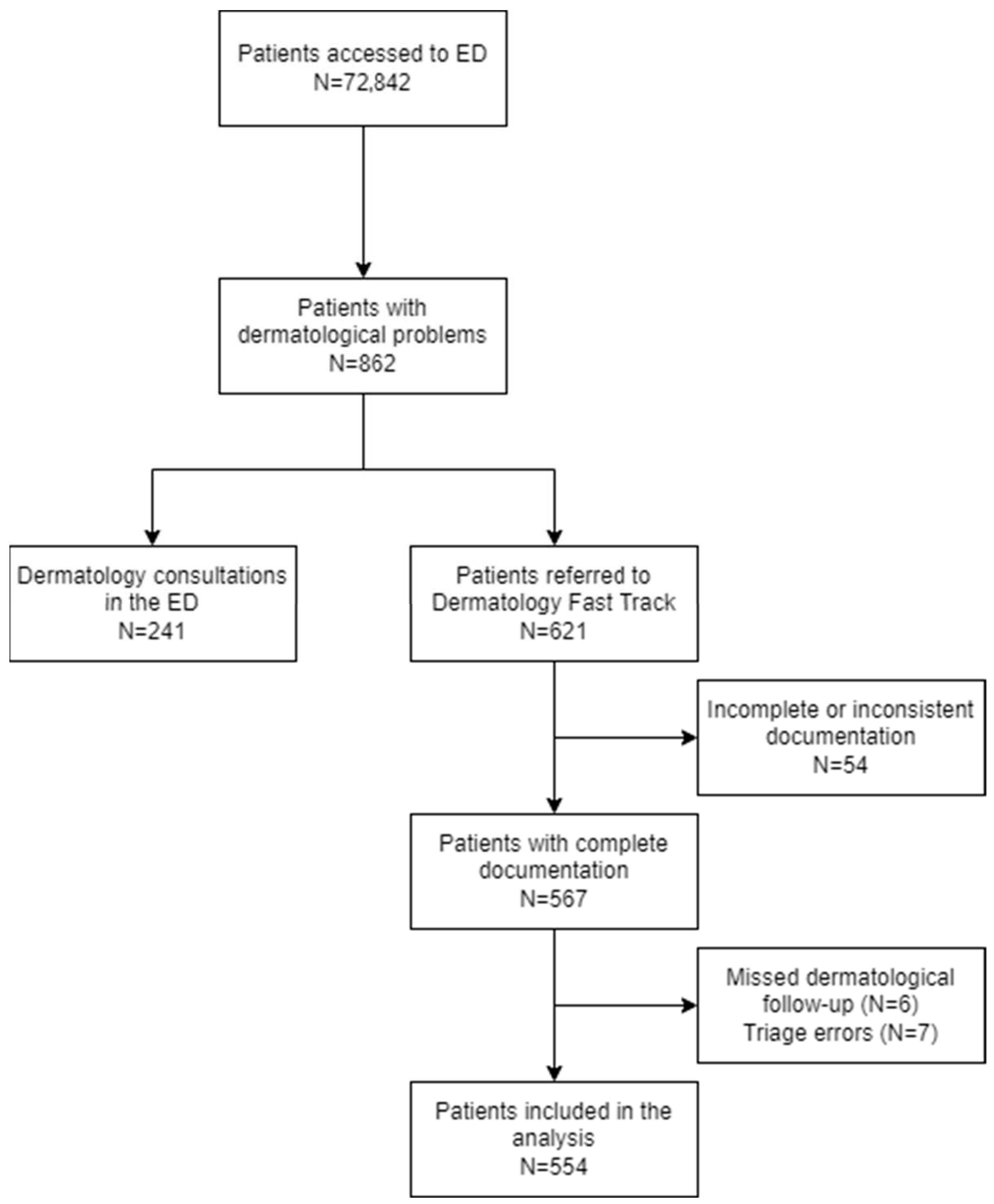

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Subjects, and Methods

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Concordance Between Admission and Discharge Priority Codes

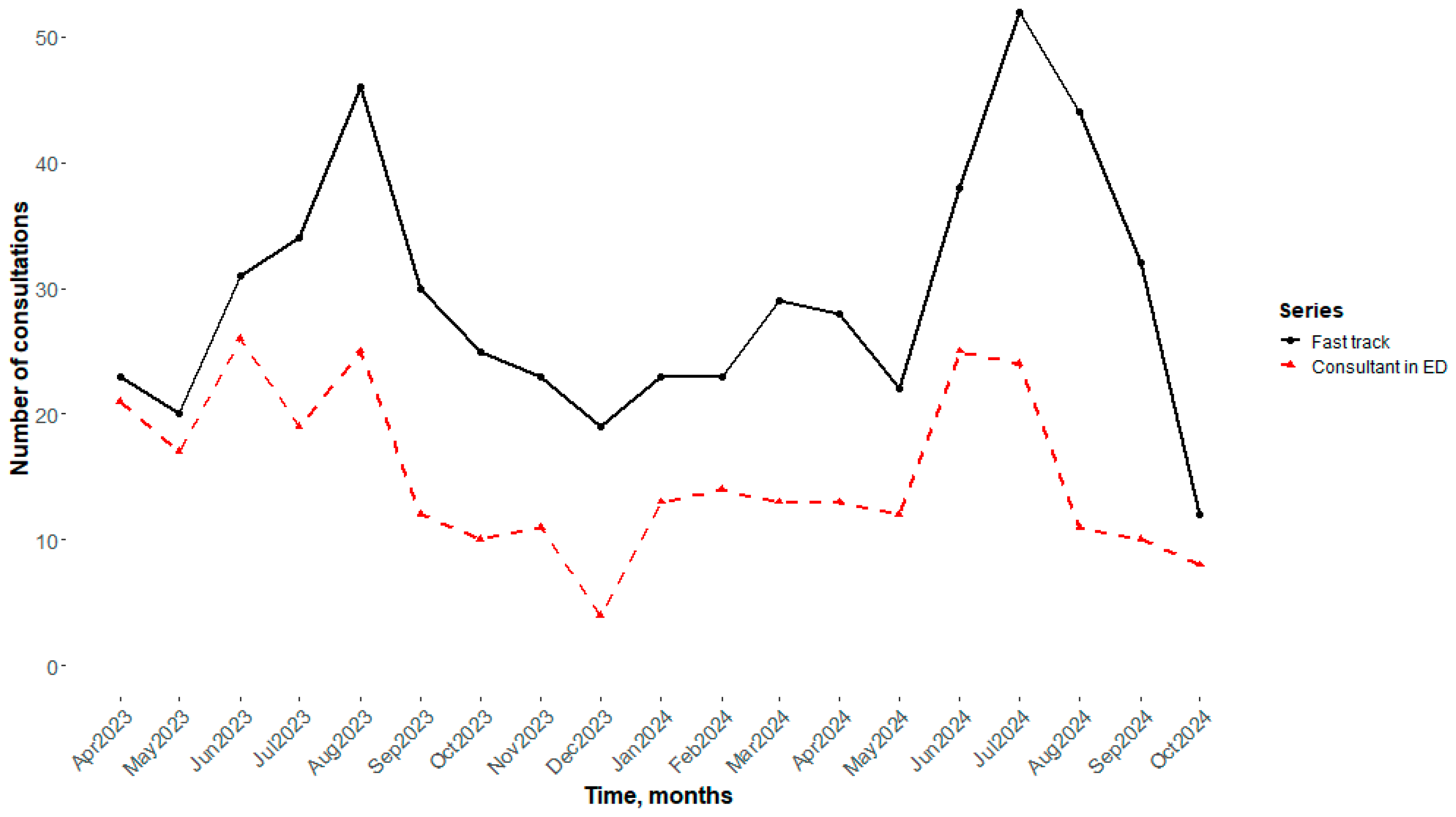

3.3. Temporal Trend of Visits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFT | Dermatologic Fast Track |

| ED | Emergency Department |

References

- Morley, C.; Unwin, M.; Peterson, G.M.; Stankovich, J.; Kinsman, L. Emergency department crowding: A systematic review of causes, consequences and solutions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pines, J.M.; Hollander, J.E. Emergency department crowding is associated with poor care for patients with severe pain. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2008, 51, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considine, J.; Kropman, M.; Kelly, E.; Winter, C. Effect of emergency department fast track on emergency department length of stay: A case-control study. Emerg. Med. J. 2008, 25, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oredsson, S.; Jonsson, H.; Rognes, J.; Lind, L.; Göransson, K.E.; Ehrenberg, A.; Asplund, K.; Castrén, M.; Farrohknia, N. A systematic review of triage-related interventions to improve patient flow in emergency departments. Scand. J. Trauma Reusc. Emerg. Med. 2011, 19, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodi, S.W.; Grau, M.V.; Orsini, C.M. Evaluation of a fast-track unit: Alignment of resources and demand results in improved satisfaction and decreased length of stay for emergency department patients. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2006, 15, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K.; Zachariah, B.; Nitschmann, J.; Psencik, B. Evaluation of the fast-track unit of a university emergency department. J Emerg. Nurs. 2007, 33, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baibergenova, A.; Shear, N.H. Skin Conditions That Bring Patients to Emergency Departments. Arch. Dermatol. 2011, 147, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, E.; Vano -Galvan, S.; Jimenez-Gomez, N.; Ballester, A.; Munoz-Zato, E.; Jaen, P. Dermatologic Emergencies: Descriptive Analysis of 861 Patients in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital. Actas. Dermosifiliogr. 2013, 104, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, D.; Yigit, O.; Kilic, T.; Buyurgan, C.S.; Dicle, O. Epidemiologic Characteristics of Patients Admitted to Emergency Department with Dermatological Complaints; a Retrospective Cross sectional Study. Arch. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2019, 7, e47. [Google Scholar]

- Algarni, A.S.; Alshiakh, S.M.; Alghamdi, S.M.; Alahmadi, M.A.; Bokhari, A.W.; Aljubayri, S.N.; Almutairy, W.A.; Alfahmi, N.M.; Samargandi, S. From Rash Decisions to Critical Conditions: A Systematic Review of Dermatological Presentations in Emergency Departments. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Martinez, M.L.; Escario-Travesedo, E.; Rodriguez-Vaquez, M.; Azana-Defez, J.M.; Martin de Hijas-Santos, M.C.; Juan-Perez-Garcia, L. Dermatology consultations in an emergency department prior to establishment of emergency dermatology cover. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011, 102, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Garcia, L.M.; Bou-Prieto, A.; Carrasquillo-Bonilla, D.; Valentin-Nogueras, S.; Figueroa-Guzman, L. Dermatologists in the Emergency Department: A 6-Year Retrospective Analysis. Puerto Rico Health Sci. J. 2015, 34, 215–218. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.Y.; Yun, S.J.; Kim, G.H.; Lee, A.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Hong, J.S. Dermatologic Diagnosis in the Emergency Department in Korea: An 11-Year Descriptive Study. Ann. Dermatol. 2020, 32, 87–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hay, R.J.; Johns, N.E.; Williams, H.C.; Bolliger, I.W.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Margolis, D.J.; Marks, R.; Naldi, L.; Weinstock, M.A.; Wulf, S.K.; et al. The global burden of skin disease in 2010: An analysis of the prevalence and impact of skin conditions. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzolo, E.; Naldi, L. Epidemiology of major chronic inflammatory immune-related skin diseases in 2019. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2020, 16, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, M.A.; Paul, C.; Nijsten, T.; Gisondi, P.; Salavastru, C.; Taieb, C.; Trakatelli, M.; Puig, L.; Stratigos, A.; EADV burden of skin diseases project team. Prevalence of most common skin diseases in Europe: A population-based study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Concia, E.; Giusti, M.; Mazzone, A.; Santini, C.; Stefani, S.; Violi, F. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in internal medicine wards: Old and new drugs. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2016, 11, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; Pagliano, P.; De Simone, G.; Pan, A.; Brambilla, P.; Gattuso, G.; Mastroianni, C.; Kertusha, B.; Contini, C.; Massoli, L.; et al. Epidemiology, aetiology and treatment of skin and soft tissue infections: Final report of a prospective multicentre national registry. J. Chemother. 2022, 34, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzza, N.; Itin, P.H.; Beltraminelli, H. Urgent consultations at the dermatology department of Basel University Hospital, Switzerland: Characterisation of patients and setting—A 12-month study with 2222 patients data and review of the literature. Dermatology 2014, 228, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alpalhao, M.; Uva, L.; Soromenho, G.; Filipe, P. Dermatological emergencies: One-year data analysis of 8,620 patients from the largest Portuguese tertiary teaching hospital. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2016, 26, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Otmy, S.S.; Abduljabbar, Z.A.; Al-Raddadi, R.M.; Farahat, F. Factors associated with non-urgent visits to the emergency department in a tertiary care centre, western Saudi Arabia: Cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e035951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnasser, S.; Alharabi, M.; Alibrahim, A.A.; Aal Ibrahim, A.A.; Kentab, O.; Alassaf, W.; Ajahany, M. Analysis of Emergency Department Use by Non-Urgent Patients and Their Visit Characteristics at an Academic Center. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2023, 16, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, J.Y.H.; Al-Manji, I.; Oakley, A. Urgency vs triage prioritisation: Appropriateness of referrer-rated urgency of referrals to a public dermatology service. N. Z. Med. J. 2025, 138, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, P.E.; Warton, E.M.; Mark, D.G.; Reed, E.M. Emergency Department Triage Accuracy and Delays in Care for High-Risk Conditions. JAMA Netw. Open. 2025, 18, e258498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rubaian, N.F.; Al Omar, R.S.; Alzahrani, A.S.; Alotaibi, F.M.; Alharbi, M.A.; Alanazi, B.S.; Almuhaidib, S.R.; Alsaadoon, N.F.; Alfaraj, D.; Al Shamlan, N.A. Epidemiological Trends and Characteristics of Dermatological Conditions Presenting to a Saudi Major Emergency Department. Open Access Emerg. Med. 2024, 16, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Astolto, R.; Quintarelli, L.; Corrà, A.; Caproni, M.; Fania, L.; Di Zenzo, G.; Didona, B.; Gasparini, G.; Cozzani, E.; Feliciani, C. Environmental factors in autoimmune bullous diseases with a focus on seasonality: New insights. Dermatol. Rep. 2023, 15, 9641. [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi, R.; Mazmudar, R.S.; Knusel, K.D.; Ezaldein, H.H.; Bordeaux, J.S.; Scott, J.F. Trends in emergency department visits due to sunburn and factors associated with severe sunburns in the United States. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dei-Cas, I.; Carrizo, D.; Giri, M.; Boyne, G.; Dominguez, N.; Novello, V.; Acuna, K.; Dei-Cas, P. Infectious skin disorders encountered in a pediatric emergency department of a tertiary care hospital in Argentina: A descriptive study. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, M.G.; Holzer, K.J.; Carbone, J.T.; Salas-Wright, C.P. Arthropod Bites and Stings Treated in Emergency Departments: Recent Trends and Correlates. Wilderness Environ. Med. 2019, 30, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Localized skin lesions (<10% BSA), excluding periorbital and oral regions *; erythematous, edematous, vesicular, urticarial, or crusted | Altered vital signs |

| Arthropod or parasite bites (e.g., tick bite), with or without parasite presence | Diffuse erythematous, urticarial, or bullous skin lesions and/or lesions associated with systemic symptoms |

| First- or second-degree burns <10% BSA (excluding face, neck, genitals, groin, axilla *, burns with dangerous mechanism or inhalation) | Chemical skin contamination |

| Single pre-existing skin lesion with recent changes and/or bleeding (e.g., melanocytic lesion) | Lesions suspicious for physical abuse or maltreatment |

| Dehiscence of surgical wounds (after dermatological procedures) | Requests for medico-legal investigations by judicial authorities |

| Nonspecific or post-traumatic abrasions (in trauma already evaluated) | Patients referred directly from other healthcare facilities (e.g., GPs, out-of-hours services, nursing homes) |

| Genital ulcers |

| Dermatological Diagnosis | N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous Infections and Infestations | Infectious 1 | 117 (21.12%) | 236 (42.60%) |

| Entomodermatoses | 69 (12.45%) | ||

| Scabies | 32 (5.78%) | ||

| Tick bites | 18 (3.25%) | ||

| Inflammatory Skin Diseases | Eczema | 98 (17.69%) | 185 (33.39%) |

| Urticaria | 26 (4.69%) | ||

| Drug eruptions | 15 (2.71%) | ||

| Psoriasis | 14 (2.53%) | ||

| Pruritus and associated lesions | 12 (2.17%) | ||

| Inflammatory skin lesions | 11 (1.99%) | ||

| Non-eczematous erythematous lesions | 9 (1.62%) | ||

| Burns | 34 (6.14%) | 34 (6.14%) | |

| Skin Tumors and Cystic Lesions | Cystic lesions | 32 (5.78%) | 42 (7.58%) |

| Neoplasms | 10 (1.81%) | ||

| Other | 57 (10.29%) | 57 (10.29%) | |

| Diagnosis | <30 Years N (%) | 30–65 Years N (%) | >65 Years N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutaneous Infections and Infestations | 63 (47.73) | 126 (40.78) | 47 (41.59) |

| Inflammatory Skin Diseases | 44 (33.33) | 102 (33.01) | 39 (34.51) |

| Burns | 7 (5.30) | 26 (8.41) | 1 (0.88) |

| Skin Tumors and Cystic Lesions | 6 (4.55) | 25 (8.09) | 11 (9.73) |

| Other | 12 (9.09) | 30 (9.71) | 15 (13.27) |

| Total | 132 (23.83%) | 309 (55.78%) | 113 (20.40%) |

| Admission Code * | Discharge Code White | Discharge Code Green | Discharge Code Blue | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 106 | 22 | 0 | 128 |

| Green | 207 | 212 | 0 | 419 |

| Blue | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Total | 313 | 234 | 7 | 554 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cammarata, E.; Airoldi, C.; Zavattaro, E.; Gavelli, F.; Fazzini, U.; Bellan, M.; Savoia, P.; on behalf of the DFT Group. The Dermatology Fast Track as a Model for Integrated Care Pathways Between Emergency Medicine and Outpatient Specialty Services. Medicina 2025, 61, 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122133

Cammarata E, Airoldi C, Zavattaro E, Gavelli F, Fazzini U, Bellan M, Savoia P, on behalf of the DFT Group. The Dermatology Fast Track as a Model for Integrated Care Pathways Between Emergency Medicine and Outpatient Specialty Services. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122133

Chicago/Turabian StyleCammarata, Edoardo, Chiara Airoldi, Elisa Zavattaro, Francesco Gavelli, Ugo Fazzini, Mattia Bellan, Paola Savoia, and on behalf of the DFT Group. 2025. "The Dermatology Fast Track as a Model for Integrated Care Pathways Between Emergency Medicine and Outpatient Specialty Services" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122133

APA StyleCammarata, E., Airoldi, C., Zavattaro, E., Gavelli, F., Fazzini, U., Bellan, M., Savoia, P., & on behalf of the DFT Group. (2025). The Dermatology Fast Track as a Model for Integrated Care Pathways Between Emergency Medicine and Outpatient Specialty Services. Medicina, 61(12), 2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122133