Early and Mid-Term Results of Solid Organ Transplantation After Circulatory Death: A 4-Year Single Centre Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

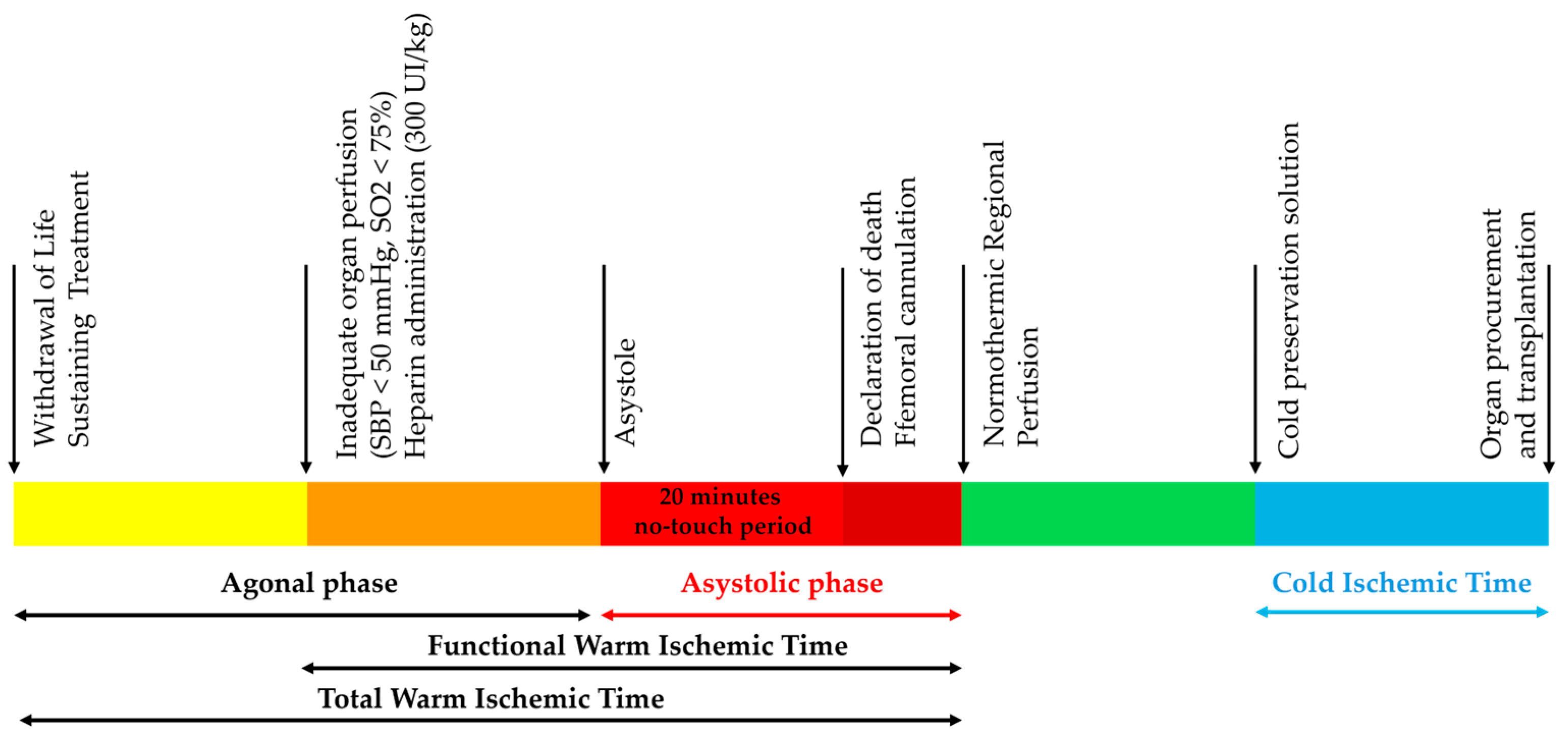

2.1. cDCD Procedure

2.2. Endpoints

2.3. Statistical Analysis

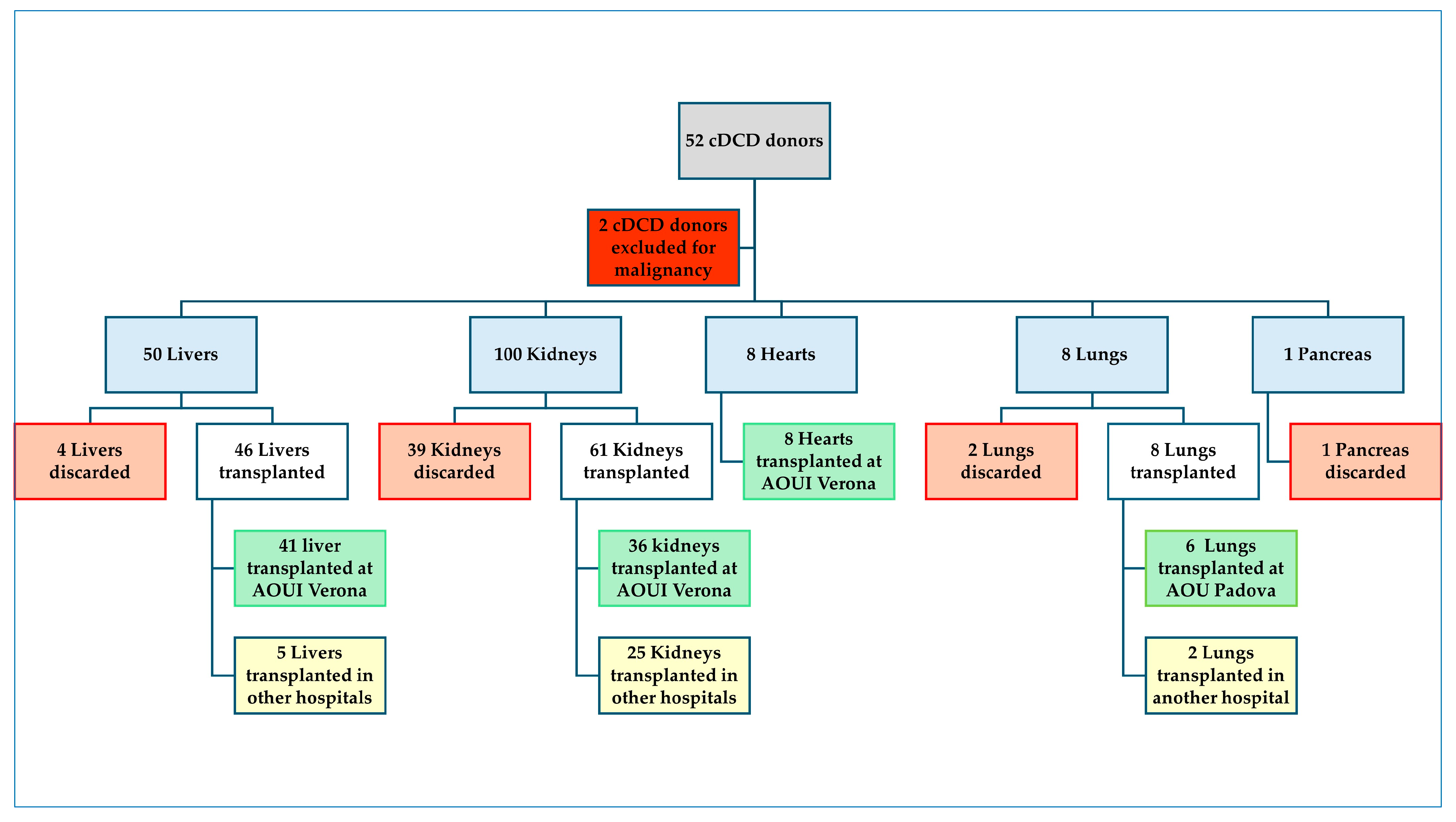

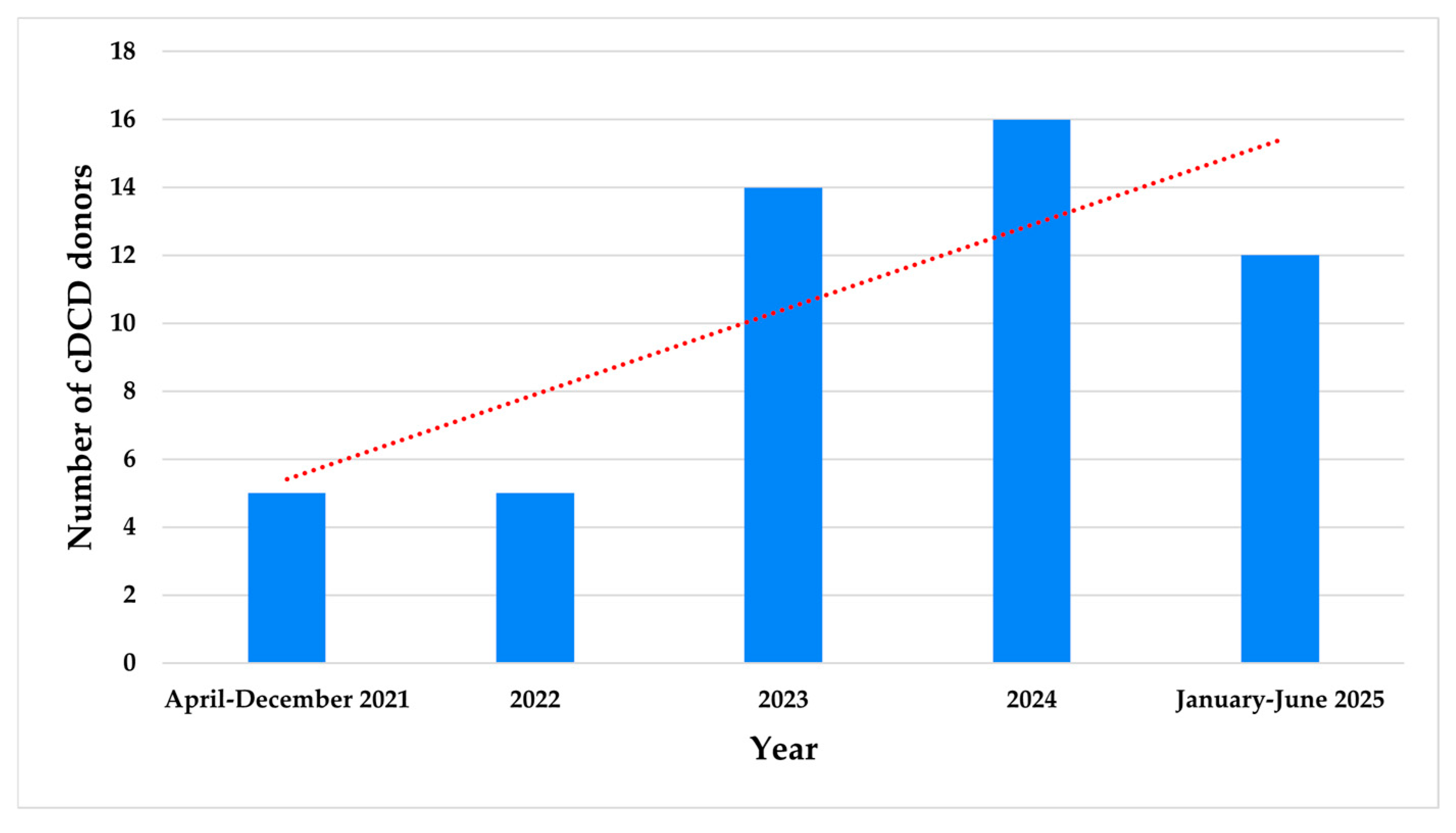

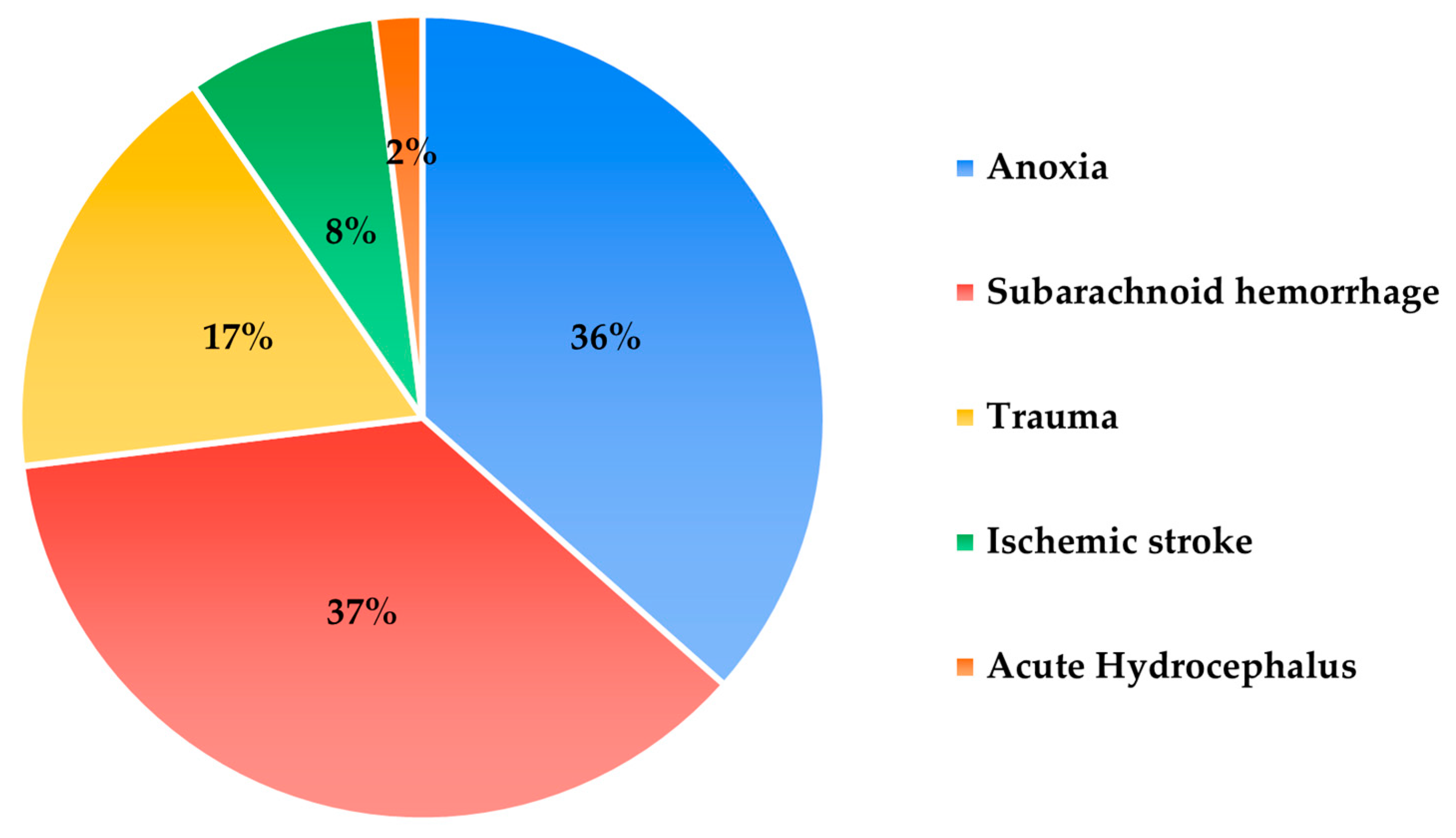

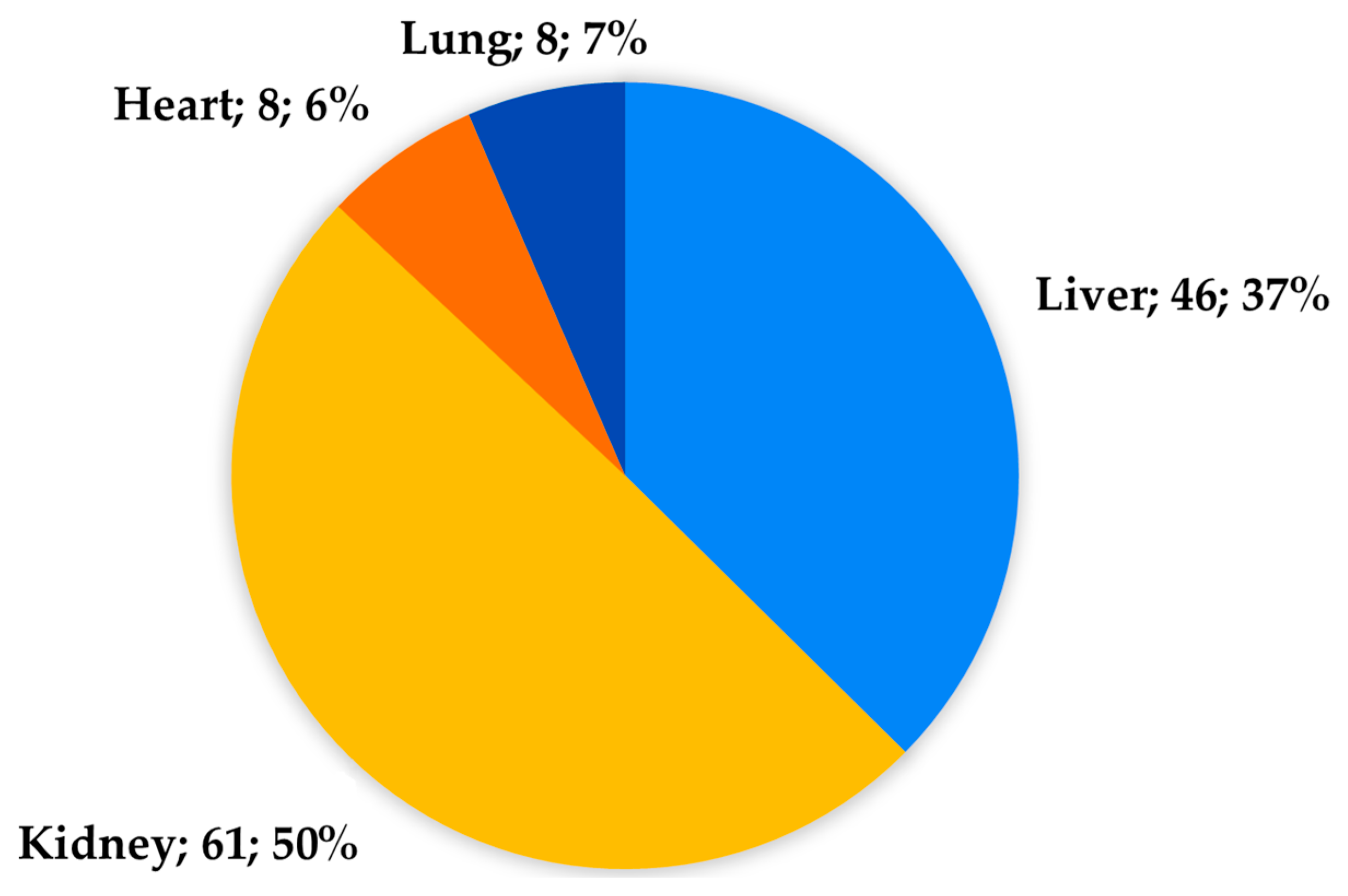

3. Results

3.1. Liver Transplantation

3.2. Kidney Transplantation

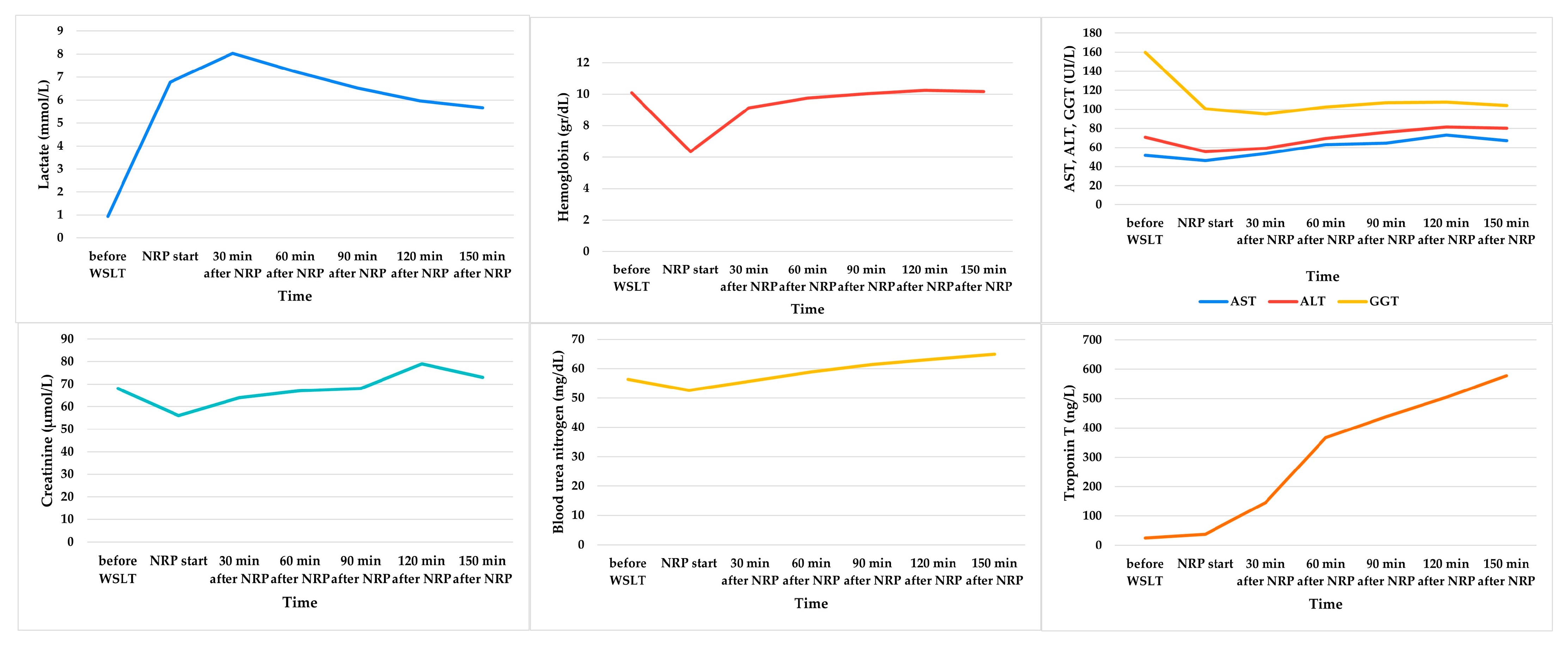

3.3. Heart Transplantation

3.4. Lung Transplantation

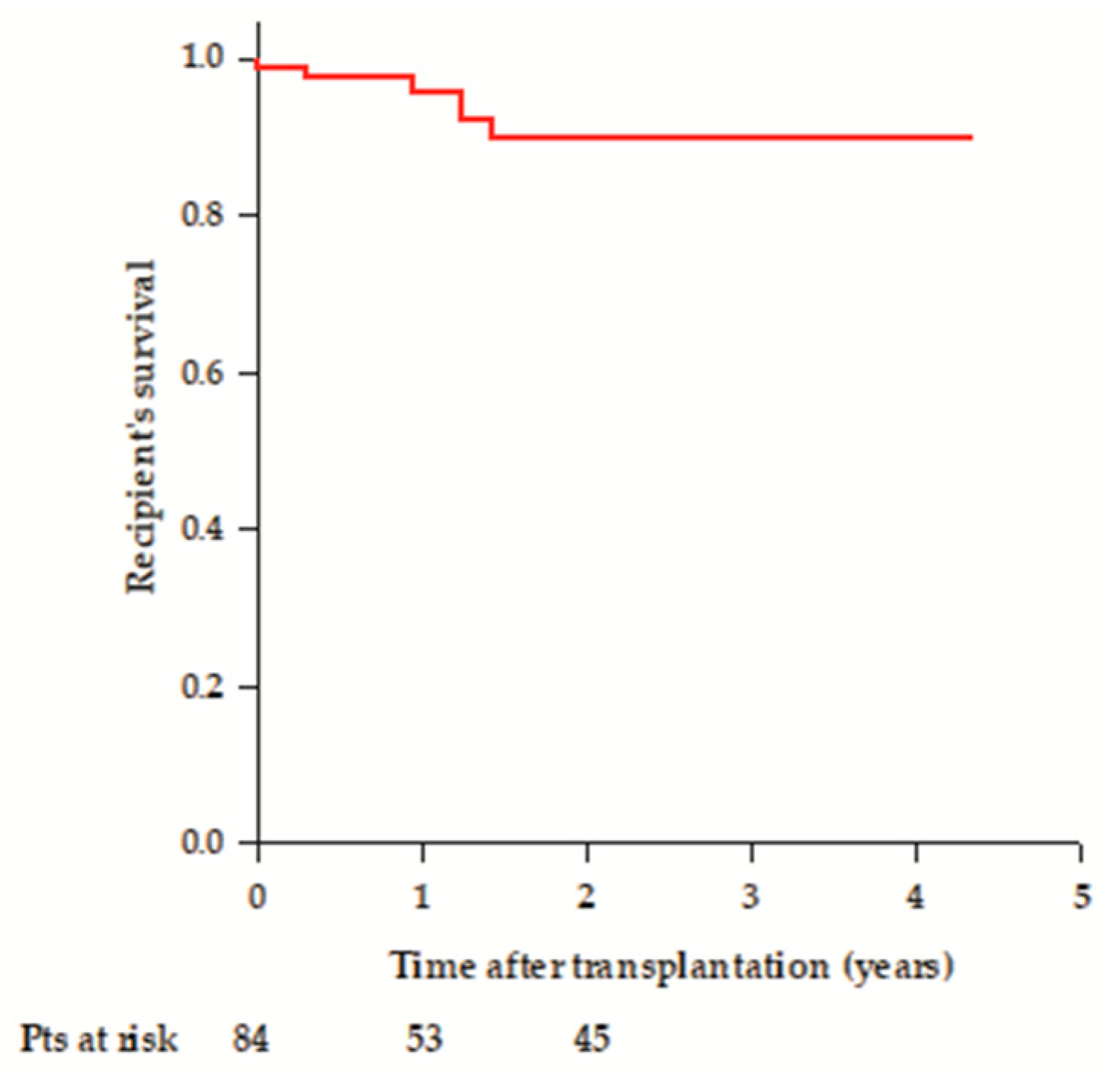

3.5. Overall Recipient’s Survival After Transplantation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADPKD | Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease |

| ALT | Alanine transaminase |

| AOUI | Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata of Verona |

| AST | Aspartate transaminase |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| cDCD | Controlled Donation after Circulatory Death |

| CLAD | Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction |

| CPB | Cardio-pulmonary bypass |

| CPFE | Combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema |

| CRRT | Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy |

| D-HOPE | Dual Hypothermic oxygenated machine perfusion |

| ECMO | Extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation |

| EVLP | Ex vivo lung perfusion |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| ILD | Interstitial Lung Disease |

| LAS | Lung allocation score |

| NMP | Normothermic machine perfusion |

| NRP | Normothermic Regional Perfusion |

| PSM | Propensity score matching |

| RAI | Rejection Activity Index |

| SLE | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| UNOS | United Network for Organ Sharing |

| WIT | Warm Ischemic Time |

| WLST | Withdrawal of Life Sustaining Therapy |

References

- Starzl, T.E.; Marchioro, T.L.; Vonkaulla, K.N.; Hermann, G.; Brittain, R.S.; Waddell, W.R. Homotransplantation of the liver in humans. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1963, 117, 659–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barnard, C.N. The operation. A human cardiac transplant: An interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S. Afr. Med. J. 1967, 41, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- A definition of irreversible coma. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA 1968, 205, 337–340. [CrossRef]

- Vodkin, I.; Kuo, A. Extended Criteria Donors in Liver Transplantation. Clin. Liver Dis. 2017, 21, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeone, A.; Lebreton, G.; Coutance, G.; Demondion, P.; Schmidt, M.; Amour, J.; Varnous, S.; Leprince, P. A single-center long-term experience with marginal donor utilization for heart transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2020, 34, e14057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Brotherton, A.; Chaudhry, D.; Evison, F.; Nieto, T.; Dabare, D.; Sharif, A. All Expanded Criteria Donor Kidneys are Equal But are Some More Equal Than Others? A Population-Cohort Analysis of UK Transplant Registry Data. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 11421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomero, M.; Gardiner, D.; Coll, E.; Haase-Kromwijk, B.; Procaccio, F.; Immer, F.; Gabbasova, L.; Antoine, C.; Jushinskis, J.; Lynch, N.; et al. Donation after circulatory death today: An updated overview of the European landscape. Transpl. Int. 2020, 33, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurotransplant International Foundation. Annual Report 2024. Available online: https://www.eurotransplant.org/statistics/annual-report (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- NHS Blood and Transplant. Organ and Tissue Donation and Transplantation. Activity Report 2024/2025. Available online: https://nhsbtdbe.blob.core.windows.net/umbraco-assets-corp/36694/activity-report-2024-2025-final.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Kootstra, G.; Daemen, J.H.; Oomen, A.P. Categories of non-heart-beating donors. Transplant. Proc. 1995, 27, 2893–2894. [Google Scholar]

- Thuong, M.; Ruiz, A.; Evrard, P.; Kuiper, M.; Boffa, C.; Akhtar, M.Z.; Neuberger, J.; Ploeg, R. New classification of donation after circulatory death donors definitions and terminology. Transpl. Int. 2016, 29, 749–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, N.; Shaw, D.; Shemie, S.; Wiebe, K.; van Mook, W.; Bollen, J. Directed Organ Donation After Euthanasia. Transpl. Int. 2023, 36, 11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorko, D.J.; Shemie, J.; Hornby, L.; Singh, G.; Matheson, S.; Sandarage, R.; Wollny, K.; Kongkiattikul, L.; Dhanani, S. Autoresuscitation after circulatory arrest: An updated systematic review. Can J Anaesth 2023, 70, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italian Law n. 578/1993. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/1994/01/08/5/sg/pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Italian Ministerial Decree n.582/1994. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/1994/10/19/245/sg/pdf (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Fernández-de la Varga, M.; Del Pozo-Del Valle, P.; Béjar-Serrano, S.; López-Andújar, R.; Berenguer, M.; Prieto, M.; Montalvá, E.; Aguilera, V. Good post-transplant outcomes using liver donors after circulatory death when applying strict selection criteria: A propensity-score matched-cohort study. Ann. Hepatol. 2022, 27, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessheimer, A.J.; Coll, E.; Torres, F.; Ruíz, P.; Gastaca, M.; Rivas, J.I.; Gómez, M.; Sánchez, B.; Santoyo, J.; Ramírez, P.; et al. Normothermic regional perfusion vs. super-rapid recovery in controlled donation after circulatory death liver transplantation. J. Hepatol. 2019, 70, 658–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hessheimer, A.J.; de la Rosa, G.; Gastaca, M.; Ruíz, P.; Otero, A.; Gómez, M.; Alconchel, F.; Ramírez, P.; Bosca, A.; López-Andújar, R.; et al. Abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in controlled donation after circulatory determination of death liver transplantation: Outcomes and risk factors for graft loss. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, C.J.E.; Hunt, F.; Messer, S.; Currie, I.; Large, S.; Sutherland, A.; Crick, K.; Wigmore, S.J.; Fear, C.; Cornateanu, S.; et al. In situ normothermic perfusion of livers in controlled circulatory death donation may prevent ischemic cholangiopathy and improve graft survival. Am. J. Transplant. 2019, 19, 1745–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagness, M.; Foss, S.; Sørensen, D.W.; Syversen, T.; Bakkan, P.A.; Dahl, T.; Fiane, A.; Line, P. Liver Transplant After Normothermic Regional Perfusion from Controlled Donors After Circulatory Death: The Norwegian Experience. Transplant. Proc. 2019, 51, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, A.L.; Sellers, M.T.; Abt, P.L.; Croome, K.P.; Merani, S.; Wall, A.; Abreu, P.; Alebrahim, M.; Baskin, R.; Bohorquez, H.; et al. US Liver Transplant Outcomes After Normothermic Regional Perfusion vs Standard Super Rapid Recovery. JAMA Surg. 2024, 159, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrovangelis, C.; Frost, C.; Hort, A.; Laurence, J.; Pang, T.; Pleass, H. Normothermic Regional Perfusion in Controlled Donation After Circulatory Death Liver Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transpl. Int. 2024, 37, 13263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, J.; Sousa Da Silva, R.; Cortes-Cerisuelo, M.; Croome, K.; De Carlis, R.; Hessheimer, A.J.; Muller, X.; de Goeij, F.; Banz, V.; Magini, G.; et al. Utilization of livers donated after circulatory death for transplantation—An international comparison. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carlis, R.; Schlegel, A.; Frassoni, S.; Olivieri, T.; Ravaioli, M.; Camagni, S.; Patrono, D.; Bassi, D.; Pagano, D.; Di Sandro, S.; et al. How to preserve liver grafts from circulatory death with long warm ischemia? A retrospective italian cohort study with normothermic regional perfusion and hypothermic oxygenated perfusion. Transplantation 2021, 105, 2385–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurink, I.J.; van de Leemkolk, F.E.M.; Fondevila, C.; De Carlis, R.; Savier, E.; Oniscu, G.C.; Huurman, V.A.L.; de Jonge, J. Donor eligibility criteria and liver graft acceptance criteria during normothermic regional perfusion: A systematic review. Liver Transpl. 2022, 28, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, M.T.; Nassar, A.; Alebrahim, M.; Sasaki, K.; Lee, D.D.; Bohorquez, H.; Cannon, R.M.; Selvaggi, G.; Neidlinger, N.; McMaster, W.G.; et al. Early United States experience with liver donation after circulatory determi-nation of death using thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion: A multi-institutional observational study. Clin. Transplant. 2022, 36, e14659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torri, F.; Balzano, E.; Melandro, F.; Maremmani, P.; Bertini, P.; Lo Pane, P.; Masini, M.; Rotondo, M.I.; Babboni, S.; Del Turco, S.; et al. Sequential Normothermic Regional Perfusion and End-ischemic Ex Situ Machine Perfusion Allow the Safe Use of Very Old DCD Donors in Liver Transplantation. Transplantation 2024, 108, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foss, S.; Nordheim, E.; Sørensen, D.W.; Syversen, T.B.; Midtvedt, K.; Åsberg, A.; Dahl, T.; Bakkan, P.A.; Foss, A.E.; Geiran, O.R.; et al. First Scandinavian Protocol for Controlled Donation After Circulatory Death Using Normothermic Regional Perfusion. Transplant. Direct 2018, 4, e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miñambres, E.; Suberviola, B.; Dominguez-Gil, B.; Rodrigo, E.; Ruiz-San Millan, J.C.; Rodríguez-San Juan, J.C.; Ballesteros, M.A. Improving the outcomes of organs obtained from controlled donation after circulatory death donors using abdominal normothermic regional perfusion. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, P.; Vázquez, D.; Rodríguez, G.; Rubio, J.J.; Pérez, M.; Portolés, J.M.; Carballido, J. Kidney transplants in controlled donation following circulatory death, or maastricht type III donors, with abdominal normothermic regional perfusion, optimizing functional outcomes. Transplant. Direct 2021, 7, e725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, M.; Coll, E.; Fernández-Pérez, C.; Pont, T.; Ruiz, Á.; Pérez-Redondo, M.; Oliver, E.; Atutxa, L.; Manciño, J.M.; Daga, D.; et al. Improved short-term outcomes of kidney transplants in controlled donation after the circulatory determination of death with the use of normothermic regional perfusion. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 3618–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoye, E.; Legeai, C.; Branchereau, J.; Gay, S.; Riou, B.; Gaudez, F.; Veber, B.; Bruyere, F.; Cheisson, G.; Kerforne, T.; et al. Optimal donation of kidney transplants after controlled circulatory death. Am. J. Transplant. 2021, 21, 2424–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravaioli, M.; De Pace, V.; Comai, G.; Capelli, I.; Baraldi, O.; D’Errico, A.; Bertuzzo, V.R.; Del Gaudio, M.; Zanfi, C.; D’ARcangelo, G.L.; et al. Preliminary experience of sequential use of normothermic and hypothermic oxygenated perfusion for donation after circulatory death kidney with warm ischemia time over the conventional criteria—A retrospective and observational study. Transpl. Int. 2018, 31, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noterdaeme, T.; Detry, O.; Hans, M.F.; Nellessen, E.; Ledoux, D.; Joris, J.; Meurisse, M.; Defraigne, J.O. What is the potential increase in the heart graft pool by cardiac donation after circulatory death? Transpl. Int. 2013, 26, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, S.; Lannon, J.; Wong, E.; Hopkinson, C.; Fielding, S.; Axell, R.; Ali, A.; Tsui, S.; Large, S. The Potential of Transplanting Hearts from Donation After Circulatory Determined Death (DCD) Donors Within the United Kingdom. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015, 34, S275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cámara, S.; Asensio-López, M.C.; Royo-Villanova, M.; Soler, F.; Jara-Rubio, R.; Garrido-Peñalver, J.F.; Pinar, E.; Hernández-Vicente, Á.; Hurtado, J.A.; Lax, A.; et al. Critical warm ischemia time point for cardiac donation after circulatory death. Am. J. Transplant. 2022, 22, 1321–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerosa, G.; Luciani, G.B.; Pradegan, N.; Tarzia, V.; Lena, T.; Zanatta, P.; Pittarello, D.; Onorati, F.; Galeone, A.; Gottin, L.; et al. Against Odds of Prolonged Warm Ischemia: Early Experience with DCD Heart Transplantation After 20-Minute No-Touch Period. Circulation 2024, 150, 1391–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, S.J.; Axell, R.G.; Colah, S.; White, P.A.; Ryan, M.; Page, A.A.; Parizkova, B.; Valchanov, K.; White, C.W.; Freed, D.H.; et al. Functional assessment and transplantation of the donor heart after circulatory death. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2016, 35, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, H.K.; Trahanas, J.; Xu, M.; Wells, Q.; Farber-Eger, E.; Pasrija, C.; Amancherla, K.; Debose-Scarlett, A.; Brinkley, D.M.; Lindenfeld, J.; et al. Outcomes of Heart Transplant Donation After Circulatory Death. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 1512–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.M.; Ahmad, A.; Bommareddi, S.; Lima, B.; Nguyen, D.; Quintana, E.; Wang, C.C.; Petrovic, M.; Siddiqi, H.K.; Amancherla, K.; et al. Normothermic regional perfusion in donation after circulatory death compared with brain dead donors: Single-center cardiac allograft outcomes. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2025, 170, 585–593.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messer, S.; Cernic, S.; Page, A.; Berman, M.; Kaul, P.; Colah, S.; Ali, J.; Pavlushkov, E.; Baxter, J.; Quigley, R.; et al. A 5-year single-center early experience of heart transplantation from donation after circulatory-determined death donors. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2020, 39, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Blanco, A.; González-Vilchez, F.; González-Costello, J.; Royo-Villanova, M.; Miñambres, E.; Cuenca, J.J.; Cánovas, S.J.; Garrido, I.P.; Moreno-González, G.; Sbraga, F.; et al. DCDD heart transplantation with thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion and static cold storage: The experience in Spain. Am. J. Transplant. 2025, 25, 1526–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manara, A.; Shemie, S.D.; Large, S.; Healey, A.; Baker, A.; Badiwala, M.; Berman, M.; Butler, A.J.; Chaudhury, P.; Dark, J.; et al. Maintaining the permanence principle for death during in situ normothermic regional perfusion for donation after circulatory death organ recovery: A United Kingdom and Canadian proposal. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20, 2017–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, J.A.; Lewis, A.; James, L.; Melmed, K.; Parent, B.; Raz, E.; Hussain, S.T.; Smith, D.E.; Moazami, N. Thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion in donation after circulatory death does not restore brain blood flow. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, J.O.; Manara, A.; Shah, A.; Schlendorf, K.; Lima, B.; Schroder, J.; Casalinova, S.; Milano, C.; Khush, K.; Luikart, H.; et al. Increasing the acceptance of thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion in DCD heart donation: A case for collaborative donor research. Am. J. Transplant. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhital, K.K.; Iyer, A.; Connellan, M.; Chew, H.C.; Gao, L.; Doyle, A.; Hicks, M.; Kumarasinghe, G.; Soto, C.; Dinale, A.; et al. Adult heart transplantation with distant procurement and ex-vivo preservation of donor hearts after circulatory death: A case series. Lancet 2015, 385, 2585–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, Y.; Scheuer, S.; Chew, H.; Ru Qiu, M.; Soto, C.; Villanueva, J.; Gao, L.; Doyle, A.M.; Takahara, S.; Jenkinson, C.M.; et al. Heart transplantation from DCD donors in Australia: Lessons learned from the first 74 cases. Transplantation 2023, 107, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasrija, C.; DeBose-Scarlett, A.; Siddiqi, H.K.; DeVries, S.A.; Keck, C.D.; Scholl, S.R.; Warhoover, M.; Schlendorf, K.H.; Shah, A.S.; Trahanas, J.M. Donation After Circulatory Death Cardiac Recovery Technique: Single-Center Observational Outcomes. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2024, 118, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Wall, A.E.; Narang, N.; Khush, K.K.; Hoffman, J.R.H.; Zhang, K.C.; Parker, W.F. Post-transplant survival after normothermic regional perfusion versus direct procurement and perfusion in donation after circulatory determination of death in heart transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2024, 43, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, P.D.; Kim, S.T.; Zappacosta, H.; White, J.P.; McKay, S.; Biniwale, R.; Ardehali, A. Severe primary graft dysfunction in heart transplant recipients using donor hearts after circulatory death: United States experience. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2025, 44, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, J.O.; Öchsner, M.; Bhagra, S.; Shah, A.; Schlendorf, K.; Lima, B.; Wang, C.C.; Siddiqi, H.; Irshad, A.; Schroder, J.; et al. Outcomes after DCD cardiac transplantation: An international, multicenter retrospective study. JACC Heart Fail. 2025. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiyar, S.S.; Maksimuk, T.E.; Gutowski, J.; Park, S.Y.; Cain, M.T.; Rove, J.Y.; Reece, T.B.; Cleveland, J.C.; Pomposelli, J.J.; Bababekov, Y.J.; et al. Association of procurement technique with organ yield and cost following donation after circulatory death. Am. J. Transplant. 2024, 24, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Chen, Q.; Roach, A.; Wolfe, S.; Osho, A.A.; Sundaram, V.; Wisel, S.A.; Megna, D.; Emerson, D.; Czer, L.; et al. Donation after circulatory death heart procurement strategy impacts utilization and outcomes of concurrently procured abdominal organs. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, M.; Castleberry, A.W.; Markin, N.W.; Chacon, M.M.; Strah, H.M.; Um, J.Y.; Berkheim, D.; Merani, S.; Siddique, A. Successful lung transplantation with graft recovered after thoracoabdominal normothermic perfusion from donor after circulatory death. Am. J. Transpl. 2022, 22, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelhouwer, C.; Vandendriessche, K.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Jochmans, I.; Monbaliu, D.; Degezelle, K.; Gunst, J.; Vandenbriele, C.; van Beersel, D.; Vos, R.; et al. Lung transplantation following donation after thoraco-abdominal normothermic regional perfusion (TA-NRP): A feasibility case study. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2022, 41, 1864–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.Y.; Hay-Arthur, E.; Bashian, E.J.; Le, H.; Schäfer, M.; Campbell, D.N.; Teman, N.R.; Gray, A.L.; Hoffman, J.R.H.; Cain, M.T. Donation after circulatory death with thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion recovery has similar outcomes with donation after brain death for lung transplantation. JHLT Open 2025, 9, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malas, J.; Chen, Q.; Thomas, J.; Emerson, D.; Megna, D.; Esmailian, F.; Bowdish, M.E.; Chikwe, J.; Catarino, P. The impact of thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion on early outcomes in donation after circulatory death lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2023, 42, 1040–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.H.; Geraci, T.C.; Piper, G.L.; Chan, J.; James, L.; Paone, D.; Sommer, P.M.; Natalini, J.; Rudym, D.; Lesko, M.; et al. Outcomes of lung and heart-lung transplants utilizing donor after circulatory death with thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion. JHLT Open 2024, 4, 100058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.T.; Park, S.Y.; Schäfer, M.; Hay-Arthur, E.; Justison, G.A.; Zhan, Q.P.; Campbell, D.; Mitchell, J.D.; Randhawa, S.K.; Meguid, R.A.; et al. Lung recovery utilizing thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion during donation after circulatory death: The Colorado experience. JTCVS Tech. 2023, 22, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasyan, A.; de la Torre, M.; Rosado Rodriguez, J.; Jauregui Abularach, A.; Romero Román, A.; Novoa Valentin, N.; Serna, I.M.; García, P.G.; Fontana, A.; Badia, G.S.; et al. Outcomes of controlled DCDD lung transplantation after thoraco-abdominal vs abdominal normothermic regional perfusion: The Spanish experience. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2025, 44, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description | Type |

|---|---|---|

| I Ia: out-of-hospital Ib: in-hospital | Unwitnessed cardiac arrest (Dead on arrival/Found dead) | Uncontrolled |

| II IIa: out-of-hospital IIb: in-hospital | Witnessed cardiac arrest (Unsuccessful resuscitation) | Uncontrolled |

| III | Awaiting cardiac arrest after WSLT | Controlled |

| IV | Cardiac arrest while brain dead | Uncontrolled/ controlled |

| V | Medically assisted cardiac arrest (Euthanasia) | Controlled |

| Donors’ Characteristics | n = 52 |

| Sex, male | 33 (63%) |

| Age, years | 74 (65–79) |

| BMI | 25 (23–29) |

| BSA | 1.8 (1.7–1.9) |

| Agonal phase, min | 13 (10–15) |

| fWIT, min | 37 (34–40) |

| tWIT, min | 40 (37–42) |

| Asystolic phase, min | 24 (23–26) |

| NRP, min | 192 (166–212) |

| A-NRP | 44 (85%) |

| TA-NRP | 8 (15%) |

| Recipients’ Characteristics | Liver Recipient (n = 41) |

|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | |

| Age, years | 58 (51–65) |

| Sex, male | 35 (85%) |

| BMI | 25 (23–28) |

| Liver disease: Alcoholic HCV infection HBV infection Autoimmune Biliary atresia Cholestasis | 19 (46%) 10 (24%) 6 (15%) 4 (10%) 1 (2%) 1 (2%) |

| Hepatocarcinoma | 21 (51%) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 3 (7%) |

| MELD score | 14 (11–26) |

| MELD Na score | 17 (11–26) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 5 (12%) |

| Cardio-respiratory support | 6 (15%) |

| Peri and post-operative characteristics | |

| Cold Ischemia, min | 240 (179–320) |

| Ex situ machine perfusion: DHOPE NMP | 21 (51%) 17 (41%) 4 (10%) |

| Primary non-function | 2 (5%) |

| ICU stay, days | 2 (1–4) |

| Hospital stay, days | 18 (13–29) |

| Hepatic artery thrombosis | 1 (2%) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 1 (2%) |

| Biliary leak | 6 (15%) |

| Anastomotic biliary stricture | 7 (17%) |

| Non-anastomotic biliary stricture | 2 (5%) |

| Ischemic cholangiopathy | 0 |

| Acute cellular rejection RAI ≥ 3 | 2 (5%) |

| Re liver transplant | 2 (5%) |

| 30-day graft survival | 39 (95%) |

| 30-day patient survival | 40 (98%) |

| Recipients’ Characteristics | Kidney Recipient (n = 32) |

|---|---|

| Preoperative characteristics | |

| Age, years | 61 (54–68) |

| Sex, male | 25 (78%) |

| BMI | 25 (23–28) |

| Kidney disease: ADPKD Chronic glomerulonephritis Nephroangiosclerosis Membranous glomerulonephritis Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis Congenital single kidney IgA nephropathy Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis Diabetic nephropathy Balkan endemic nephropathy SLE Wegener granulomatosis Vesicoureteral Reflux Obstructive uropathy | 8 (25%) 6 (17%) 4 (13%) 2 (6%) 2 (6%) 2 (6%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) 1 (3%) |

| Dialysis: Hemodialysis Peritoneal dialysis | 18 (56%) 11 (34%) |

| Pre-emptive kidney transplant | 3 (9%) |

| Peri and post-operative characteristics | |

| Ex situ machine perfusion | 10 (31%) |

| Cold ischemic time, hours | 6 (5–7) |

| Double kidney transplant | 4 (13%) |

| Primary non-function | 0 |

| Delayed graft function | 3 (9%) |

| Acute cellular rejection | 0 |

| Re-transplant | 0 |

| 30-day graft survival | 31 (97%) |

| 30-day patient survival | 32 (100%) |

| Recipients’ Characteristics | Heart Recipients (n = 8) |

|---|---|

| Pre-operative characteristics | |

| Age, years | 63 (58–68) |

| Sex, male | 7 (88%) |

| BMI | 26 (23–32) |

| BSA, m2 | 2 (1.8–2.1) |

| Cardiomyopathy: Dilatative Ischemic Valvular Endocardial fibroelastosis | 3 (38%) 3 (38%) 1 (12%) 1 (12%) |

| Diabetes | 3 (38%) |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 1 (12%) |

| Redo surgery | 2 (25%) |

| LVAD | 1 (12%) |

| Status at transplant: 2A 2B | 2 (25%) 6 (75%) |

| Waiting list time, days | 190 (39–615) |

| Intra and peri-operativecharacteristics | |

| Cold ischemic time, min | 76 (67–84) |

| CPB, min | 166 (130–200) |

| Primary graft dysfunction | 0 |

| ECMO/IABP | 0 |

| Lactate peak, mmol/L | 7 (4–13) |

| Troponin T peak, ng/L | 2389 (1804–2770) |

| CRRT | 2 (25%) |

| Mechanical ventilation, days | 4 (2–5) |

| ICU stay, days | 7 (5–11) |

| Hospital stay, days | 32 (24–34) |

| Post-operative characteristics | |

| Acute cellular rejection grade ≥ 2R | 2 (25%) |

| Cardiac allograft vasculopathy | 1 (12%) |

| LVEF at last follow-up, % | 60 (57–60) |

| Re-transplant | 0 |

| 30-day graft survival | 8 (100%) |

| 30-day patient survival | 8 (100%) |

| Recipients’ Characteristics | Lung Recipients (n = 3) |

|---|---|

| Pre-operative characteristics | |

| Age, years | 64 (64–65) |

| Sex, male | 2 (67%) |

| Lung disease: CPFE Emphysema ILD | 1 (33%) 1 (33%) 1 (33%) |

| LAS | 37 (33–38) |

| Hospitalization | 0 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 0 |

| ECMO | 0 |

| Waiting list time, days | 5 (19–60) |

| Intra and peri-operative characteristics | |

| EVLP | 1 (33%) |

| Cold ischemia, min Right lung Left lung | 275 (272–317) 190 (183–240) |

| Intra-operative ECMO time, min | 188 (163–208) |

| Bilateral lung transplant | 3 (100%) |

| Primary graft dysfunction ≥ 2: T0 T24 T48 T72 | 2 (67%) 2 (67%) 1 (33%) 1 (33%) |

| Mechanical ventilation, hours | 24 (12–42) |

| ICU stay, days | 6 (5–6) |

| Hospital stay, days | 30 (29–38) |

| Post-operative characteristics | |

| Bronchial stenosis | 1 (33%) |

| Acute cellular rejection | 0 |

| CLAD | 0 |

| Re-transplant | 0 |

| 30-day graft survival | 3 (100%) |

| 30-day patient survival | 3 (100%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galeone, A.; Casartelli Liviero, M.; Borin, A.; Nguefouet Momo, R.E.; Gottin, L.; Onorati, F.; Maffei, I.; Schiavon, M.; Persona, P.; Menon, T.; et al. Early and Mid-Term Results of Solid Organ Transplantation After Circulatory Death: A 4-Year Single Centre Experience. Medicina 2025, 61, 2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122126

Galeone A, Casartelli Liviero M, Borin A, Nguefouet Momo RE, Gottin L, Onorati F, Maffei I, Schiavon M, Persona P, Menon T, et al. Early and Mid-Term Results of Solid Organ Transplantation After Circulatory Death: A 4-Year Single Centre Experience. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122126

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaleone, Antonella, Marilena Casartelli Liviero, Alex Borin, Rostand Emmanuel Nguefouet Momo, Leonardo Gottin, Francesco Onorati, Irene Maffei, Marco Schiavon, Paolo Persona, Tiziano Menon, and et al. 2025. "Early and Mid-Term Results of Solid Organ Transplantation After Circulatory Death: A 4-Year Single Centre Experience" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122126

APA StyleGaleone, A., Casartelli Liviero, M., Borin, A., Nguefouet Momo, R. E., Gottin, L., Onorati, F., Maffei, I., Schiavon, M., Persona, P., Menon, T., Boschiero, L., Antonelli, A., Luciani, G. B., & Carraro, A. (2025). Early and Mid-Term Results of Solid Organ Transplantation After Circulatory Death: A 4-Year Single Centre Experience. Medicina, 61(12), 2126. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122126