Trends in Sudden Death Among Schizophrenia Inpatients

Abstract

1. Introduction

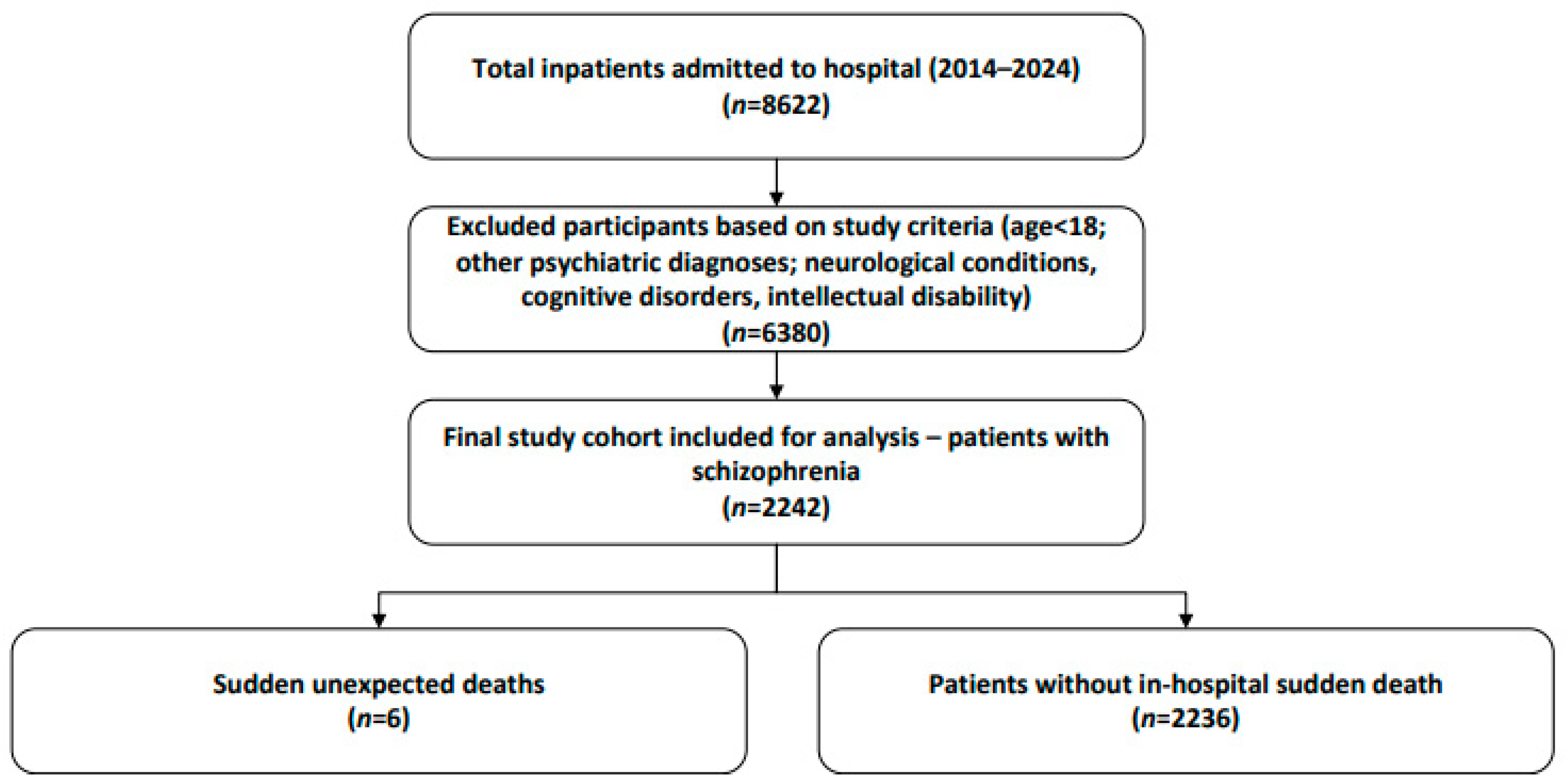

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Definition of Sudden Death

2.4. Data Collection and Ethics

2.5. Statistical Analyses

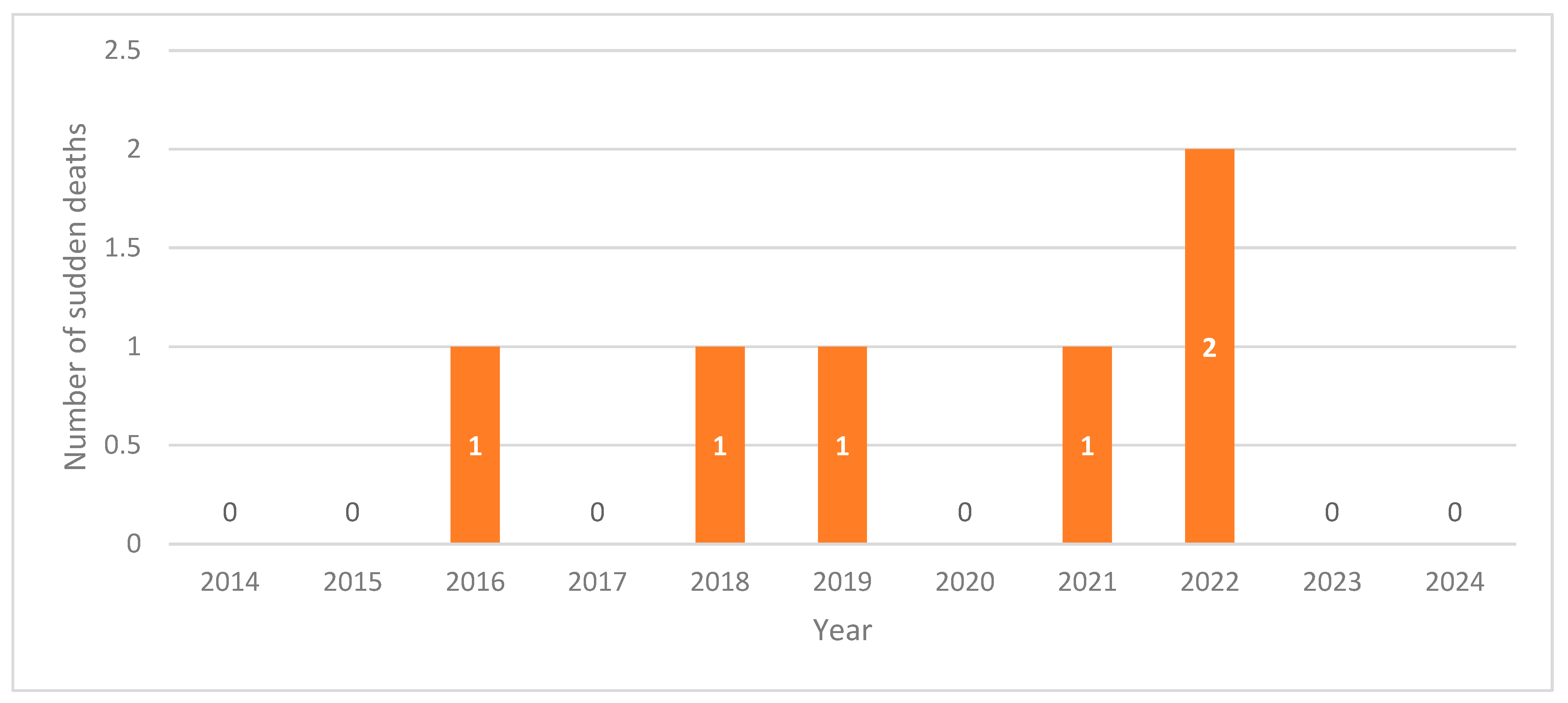

3. Results

3.1. Causes of Death

3.2. Case Descriptions

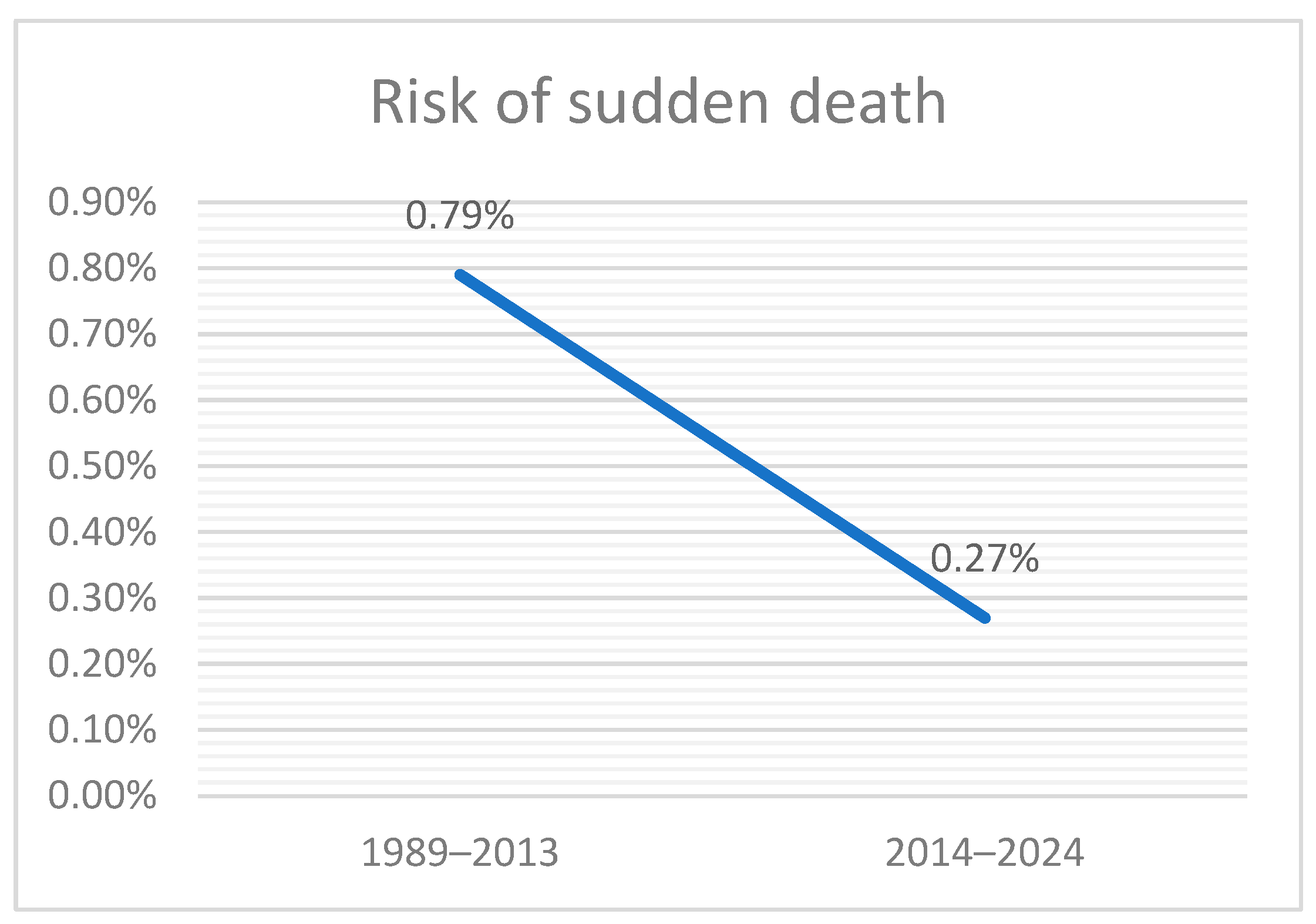

3.3. Comparison with Historical Cohort

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| PLN | Phospholamban |

| ANKRD1 | Ankyrin Repeat Domain 1 |

| CALN1 | Calneuron 1 |

| CACNA1A | Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel Subunit Alpha1 A |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| VCAM-1 | Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| ICAM-1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| LAI | Long-Acting Injectable |

| SCD | Sudden cardiac death |

| SMR | Standardized mortality ratio |

| DUP | Duration of untreated psychosis |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| FGAs | First-generation antipsychotics |

| SGAs | Second-generation antipsychotics |

References

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Veronese, N.; Bortolato, B.; Rosson, S.; Santonastaso, P.; Thapa-Chhetri, N.; Fornaro, M.; Gallicchio, D.; Collantoni, E.; et al. Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bushe, C.J.; Taylor, M.; Haukka, J. Mortality in schizophrenia: A measurable clinical endpoint. J. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 24, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zipes, D.P.; Wellens, H.J. Sudden cardiac death. Circulation 1998, 98, 2334–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, P.; Kane, J.M.; Correll, C.U. Sudden deaths in psychiatric patients. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2011, 72, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, L.; Thomas, S.; Ferrier, N.; Lewis, G.; Shaw, J.; Amos, T. Sudden unexplained death in psychiatric in-patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 2000, 176, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ifteni, P.; Correll, C.U.; Burtea, V.; Kane, J.M.; Manu, P. Sudden unexpected death in schizophrenia: Autopsy findings in psychiatric inpatients. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 155, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeting, J.; Duflou, J.; Semsarian, C. Postmortem analysis of cardiovascular deaths in schizophrenia: A 10-year review. Schizophr. Res. 2013, 150, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Blanchard, T.G.; Fowler, D.R.; Li, L. Causes of Sudden Unexpected Death in Schizophrenia Patients: A Forensic Autopsy Population Study. Am. J. Forensic Med. Pathol. 2019, 40, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujkanovic, J.; Warming, P.E.; Kessing, L.V.; Køber, L.V.; Winkel, B.G.; Lynge, T.H.; Tfelt-Hansen, J. Nationwide burden of sudden cardiac death among patients with a psychiatric disorder. Heart 2024, 110, 1365–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paratz, E.D.; van Heusden, A.; Zentner, D.; Morgan, N.; Smith, K.; Thompson, T.; James, P.; Connell, V.; Pflaumer, A.; Semsarian, C.; et al. Sudden Cardiac Death in People With Schizophrenia: Higher Risk, Poorer Resuscitation Profiles, and Differing Pathologies. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2023, 9, 1310–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas, J.; Miranda, C.; Restrepo, A.; Hernández, M.; Erazo, J.M.; Martínez, M.J.; Lasso, J.; López, L.; Gómez-Mesa, J.E. Cardiovascular Risk Evaluation in a Latin American Population With Severe Mental Illness: An Observational Study. Actas Esp. Psiquiatr. 2025, 53, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Dev, S.I.; Chen, G.; Liou, S.C.; Martin, A.S.; Irwin, M.R.; Carroll, J.E.; Tu, X.; Jeste, D.V.; Eyler, L.T. Abnormal levels of vascular endothelial biomarkers in schizophrenia. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2018, 268, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmawla, N.; Mitchell, A.J. Sudden cardiac death and antipsychotics. Part 1: Risk factors and mechanisms. Adv. Psychiatr. Treat. 2006, 12, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refisch, A.; Schumann, A.; Gupta, Y.; Schulz, S.; Voss, A.; Malchow, B.; Bär, K.-J. Characterization of cardiac autonomic dysfunction in acute Schizophrenia: A cluster analysis of heart rate variability parameters. Schizophrenia 2025, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, K.-J. Cardiac Autonomic Dysfunction in Patients with Schizophrenia and Their Healthy Relatives—A Small Review. Front. Neurol. 2015, 6, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-S.; Song, Z.-Y.; Chen, X.-L.; Bo, Y.-M.; Li, L.-L. Heart abnormality associates with a wide spectrum of psychiatric disorders: Evidence from Mendelian randomization analyses. World J. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1988–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treur, J.L.; Thijssen, A.B.; Smit, D.J.A.; Tadros, R.; Veeneman, R.R.; Denys, D.; Vermeulen, J.M.; Barc, J.; Bergstedt, J.; Pasman, J.A.; et al. Associations of schizophrenia with arrhythmic disorders and electrocardiogram traits: Genetic exploration of population samples. Br. J. Psychiatry 2025, 226, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vohra, J.; Thompson, T.; Morgan, N.; Parsons, S.; Zentner, D.; Thompson, B.; Verma, K.; Winship, I. A Study of Sudden Cardiac Death in Schizophrenia. Heart Lung Circ. 2025, 34, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ma, L.; Bo, Y.; Xia, B.; Guo, Y.; Shang, Y.; Yan, F.; Huang, E.; Shi, W.; Ding, R.; et al. Single-nucleus RNA sequencing and machine learning identify CACNA1A as a myocyte-specific biomarker for sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia. Forensic Sci. Int. 2025, 377, 112646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaylaci, S.; Tamer, A.; Kocayigit, I.; Gunduz, H. Atrıal fıbrıllatıon due to olanzapıne overdose. Clin. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.-H.; Lo, L.-W.; Liou, Y.-J.; Shu, J.-H.; Hsu, H.-C.; Liang, Y.; Huang, C.-C.; Huang, P.-H.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, J.-W.; et al. Antipsychotic treatment is associated with risk of atrial fibrillation: A nationwide nested case-control study. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 227, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, R.A.J.; Fuller, M.A.; Popli, A. Clozapine Induced Atrial Fibrillation. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1998, 18, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.-S.; Lin, C.-C.; Chang, C.-M.; Wu, K.-Y.; Liang, H.-Y.; Huang, Y.-W.; Tsai, H.-J. Antipsychotic treatment and the occurrence of venous thromboembolism: A 10-year nationwide registry study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2013, 74, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakov, E.A.; Dmitrieva, E.M.; Parshukova, D.A.; Kazantseva, D.V.; Vasilieva, A.R.; Smirnova, L.P. Oxidative Stress-Related Mechanisms in Schizophrenia Pathogenesis and New Treatment Perspectives. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 8881770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pini, S.; Raia, A.; Carpita, B.; Nardi, B.; Benvenuti, M.; Scatena, A.; Di Paolo, M. Unexplained Coma and Sudden Death in Psychiatric Patients Due to Self-Induced Water Intoxication: Clinical Insights and Autopsy Findings From Two Fatal Cases. Cureus 2025, 17, e79813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneeweiss, S.; Avorn, J. Antipsychotic agents and sudden cardiac death--how should we manage the risk? N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 294–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, W.A.; Chung, C.P.; Murray, K.T.; Hall, K.; Stein, C.M. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Hou, W.; Xu, Y.; Ji, F.; Wang, G.; Chen, C.; Lin, C.; Lin, X.; Li, J.; Zhuo, C.; et al. Antipsychotic drugs and sudden cardiac death: A literature review of the challenges in the prediction, management, and future steps. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 281, 112598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-Q.; Tang, X.-R.; Li, L.-L. Antipsychotics cardiotoxicity: What’s known and what’s next. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 736–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhang, M.-L.; Tang, X.-R.; Li, X.-Q.; Wang, J.; Li, L.-L. Cardiotoxicity of current antipsychotics: Newer antipsychotics or adjunct therapy? World J. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, S.; Bilker, W.B.; Knauss, J.S.; Margolis, D.J.; Kimmel, S.E.; Reynolds, R.F.; Glasser, D.B.; Morrison, M.F.; Strom, B.L. Cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia in patients taking antipsychotic drugs: Cohort study using administrative data. BMJ 2002, 325, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvo, F.; Pariente, A.; Shakir, S.; Robinson, P.; Arnaud, M.; Thomas, S.; Raschi, E.; Fourrier-Réglat, A.; Moore, N.; Sturkenboom, M.; et al. Sudden cardiac and sudden unexpected death related to antipsychotics: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 99, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Tsai, Y.; Tsai, H. Antipsychotic Drugs and the Risk of Ventricular Arrhythmia and/or Sudden Cardiac Death: A Nation-wide Case-Crossover Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2025, 4, e001568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, H.; Crotti, L.; Aiba, T.; Spazzolini, C.; Denjoy, I.; Fressart, V.; Hayashi, K.; Nakajima, T.; Ohno, S.; Makiyama, T.; et al. The genetics underlying acquired long QT syndrome: Impact for genetic screening. Eur. Heart J. 2016, 37, 1456–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Zuccarello, P.; Sessa, F.; Capasso, E.; Giorgetti, A.; Pesaresi, M.; Salerno, M.; Barbera, N.; Pomara, C. Sudden cardiac death in young adults and the role of antipsychotic drugs: A multicenter autopsy study. Forensic Sci. Med. Pathol. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yan, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Yan, F. Sudden Cardiac Death in Schizophrenia During Hospitalization: An Autopsy-Based Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 933025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; He, M.; Andersen, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Li, L. Sudden unexplained death in schizophrenia patients: An autopsy-based comparative study from China. Asian J. Psychiatr. 2023, 79, 103314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, K.-P.; Liao, W.-L.; Ho, P.-S.; Lin, J.-W.; Tung, C.-L.; Yang, Y.-H.; Hung, C.-S.; Tsai, J.-H. Association of antipsychotic formulations with sudden cardiac death in patients with schizophrenia: A nationwide population-based case-control study. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 342, 116171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Choudhary, H.; Chawla, N. Association of antipsychotic formulations with sudden cardiac death in patients with schizophrenia: A nationwide population-based case-control study: Letter to the editor. Psychiatry Res. 2025, 343, 116299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ma, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, X.; Wei, X.; Han, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, T. Mapping the Knowledge of Antipsychotics-Induced Sudden Cardiac Death: A Scientometric Analysis in CiteSpace and VOSviewer. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 925583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruschena, D.; Mullen, P.E.; Burgess, P.; Cordner, S.M.; Barry-Walsh, J.; Drummer, O.H.; Palmer, S.; Browne, C.; Wallace, C. Sudden death in psychiatric patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1998, 172, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drevinskaite, M.; Kaceniene, A.; Germanavicius, A.; Smailyte, G. Increased mortality risk in people with schizophrenia in Lithuania 2001–2020. Schizophrenia 2025, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, A.-V.; Ifteni, P.I.; Țâbian, D.; Petric, P.S.; Teodorescu, A. What is behind the 17-year life expectancy gap between individuals with schizophrenia and the general population? Schizophrenia 2025, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Ramcharran, D.; Yang, C.-W.W.; Chang, C.-C.; Chuang, P.-Y.; Qiu, H.; Chung, K.-H. A nationwide study of the risk of all-cause, sudden death, and cardiovascular mortality among antipsychotic-treated patients with schizophrenia in Taiwan. Schizophr. Res. 2021, 237, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz Diaz, J.C.; Frenkel, D.; Aronow, W.S. The relationship between atypical antipsychotics drugs, QT interval prolongation, and torsades de pointes: Implications for clinical use. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2020, 19, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, S.M.J.M.; Bleumink, G.S.; Dieleman, J.P.; van der Lei, J.; ’t Jong, G.W.; Kingma, J.H.; Sturkenboom, M.C.J.M.; Stricker, B.H.C. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch. Intern. Med. 2004, 164, 1293–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, P.M.; Taylor, M.; Niaz, O.S. First-generation antipsychotic long-acting injections v. oral antipsychotics in schizophrenia: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br. J. Psychiatry. Suppl. 2009, 52, S20–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koponen, H.; Alaräisänen, A.; Saari, K.; Pelkonen, O.; Huikuri, H.; Raatikainen, M.J.P.; Savolainen, M.; Isohanni, M. Schizophrenia and sudden cardiac death: A review. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2008, 62, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Hert, M.; Mazereel, V.; Stroobants, M.; De Picker, L.; Van Assche, K.; Detraux, J. COVID-19-Related Mortality Risk in People With Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic and Critical Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 798554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, A.L.; Krause, T.M.; Ghosh, L.; Shahani, L.; Machado-Vieira, R.; Lane, S.D.; Boerwinkle, E.; Soares, J.C. Analysis of COVID-19 Infection and Mortality Among Patients With Psychiatric Disorders, 2020. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2134969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, H.F.; Tahir, M.; Faheem, M.S.B.; Khabir, M.; Tahir, A.; Qureshi, M.A.A.; Ashraf, D.A.; Iqbal, M.S.; Samadi, S. Trends in schizophrenia-related mortality from 1999 to 2020: Year, gender, and regional variations. Ann. Med. Surg. 2025, 87, 4336–4343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luykx, J.J.; Correll, C.U.; Manu, P.; Tanskanen, A.; Hasan, A.; Tiihonen, J.; Taipale, H. Pneumonia Risk, Antipsychotic Dosing, and Anticholinergic Burden in Schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiatry 2024, 81, 967–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, C.; Liao, Y. Analysis of risk factors for hospital-acquired pneumonia in schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1414332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, A.-A.; Ifteni, P.I.; Lungu, A.-E.; Dragomirescu, E.-L.; Dima, L.; Teodorescu, A. Pre- and Post- COVID-19 Pandemic Pneumonia Rates in Hospitalized Schizophrenia Patients. Medicina 2025, 61, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, B.; Nordt, C.; Rössler, W. Trends in psychiatric hospitalisation of people with schizophrenia: A register-based investigation over the last three decades. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 97, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.T.H.; Chan, J.K.N.; Chiu, W.C.Y.; Tsang, L.L.W.; Chan, K.S.W.; Wong, M.M.C.; Wong, H.H.; Pang, P.F.; Chang, W.C. Risk of mortality and complications in patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. J. Eur. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2025, 91, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringen, P.A.; Engh, J.A.; Birkenaes, A.B.; Dieset, I.; Andreassen, O.A. Increased mortality in schizophrenia due to cardiovascular disease—A non-systematic review of epidemiology, possible causes, and interventions. Front. Psychiatry 2014, 5, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritogiannis, V.; Ninou, A.; Samakouri, M. Mortality in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders: Recent Advances in Understanding and Management. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCreadie, R.G. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: Descriptive study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybakowski, J. Infections and mental diseases: From tuberculosis to COVID-19. Psychiatr. Pol. 2022, 56, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinowska, S.; Trześniowska-Drukała, B.; Kłoda, K.; Safranow, K.; Misiak, B.; Cyran, A.; Samochowiec, J. The Association between Lifestyle Choices and Schizophrenia Symptoms. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aymerich, C.; Pedruzo, B.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Madaria, L.; Goena, J.; Sanchez-Gistau, V.; Fusar-Poli, P.; McGuire, P.; González-Torres, M.Á.; Catalan, A. Sexually transmitted infections, sexual life and risk behaviours of people living with schizophrenia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2024, 10, e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicala, G.; Barbieri, M.A.; Spina, E.; de Leon, J. A comprehensive review of swallowing difficulties and dysphagia associated with antipsychotics in adults. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 12, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cause of Death | Number of Patients (n = 6) |

|---|---|

| Mechanical asphyxia | 2 (33.33%) |

| Cardiovascular causes | 3 (50%) |

| Respiratory infection (bronchopneumonia) | 1 (16.67%) |

| Study Period | Total Schizophrenia Patients | Sudden Deaths | Deaths per 1000 Inpatients | Annualized Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1989–2013 | 7189 | 57 | 7.93 | 2.375 |

| 2014–2024 | 2242 | 6 | 2.68 | 0.60 |

| Characteristics | 1989–2013 [6] (n = 51) | 2014–2024 (n = 6) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ± SD) | 55.9 ± 9.4 | 53.2 ± 17.8 | 0.55 |

| Male gender (%) | 56.9 | 66.7 | 0.65 |

| Duration of schizophrenia (years ± SD) | 27.7 ± 10.3 | 28.7 ± 17.7 | 0.83 |

| Length of stay (days ± SD) | 11.7 ± 7.6 | 9.2 ± 5.6 | 0.4356 |

| First-generation antipsychotics (%) | 83.4 | 0 | <0.0001 |

| Second-generation antipsychotics (%) | 15.7 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| Benzodiazepines (%) | 74.5 | 50 | 0.21 |

| Mood stabilizers (%) | 35.3 | 50 | 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popa, A.-V.; Ifteni, P.I.; Petric, P.S.; Țâbian, D.; Teodorescu, A. Trends in Sudden Death Among Schizophrenia Inpatients. Medicina 2025, 61, 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122081

Popa A-V, Ifteni PI, Petric PS, Țâbian D, Teodorescu A. Trends in Sudden Death Among Schizophrenia Inpatients. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122081

Chicago/Turabian StylePopa, Andreea-Violeta, Petru Iulian Ifteni, Paula Simina Petric, Daniel Țâbian, and Andreea Teodorescu. 2025. "Trends in Sudden Death Among Schizophrenia Inpatients" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122081

APA StylePopa, A.-V., Ifteni, P. I., Petric, P. S., Țâbian, D., & Teodorescu, A. (2025). Trends in Sudden Death Among Schizophrenia Inpatients. Medicina, 61(12), 2081. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122081