Importance of Secondary Prevention in Coronary Heart Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patient Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

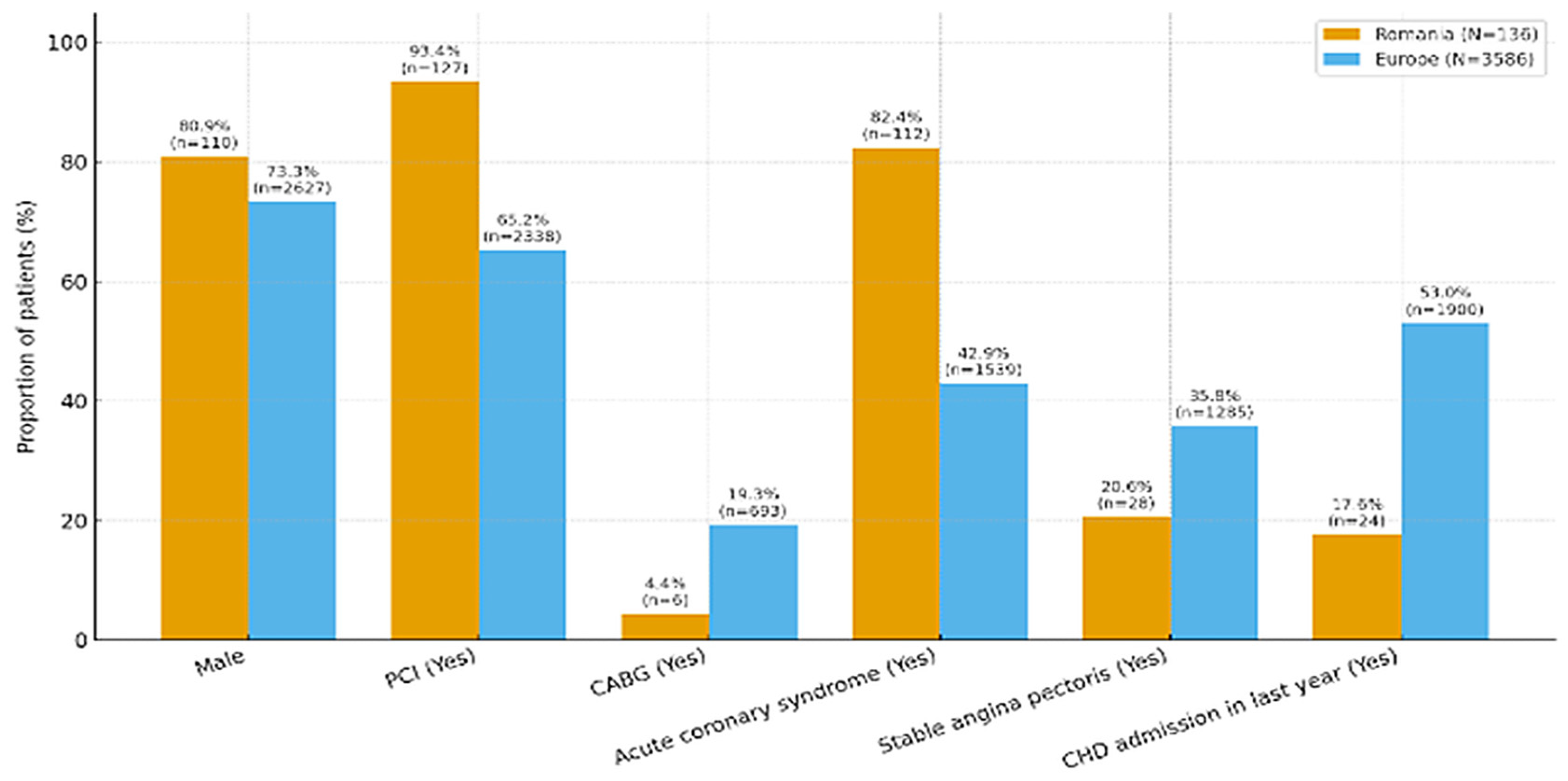

- Male sex: higher in Romania (80.9%) than Europe (73.3%); p = 0.048

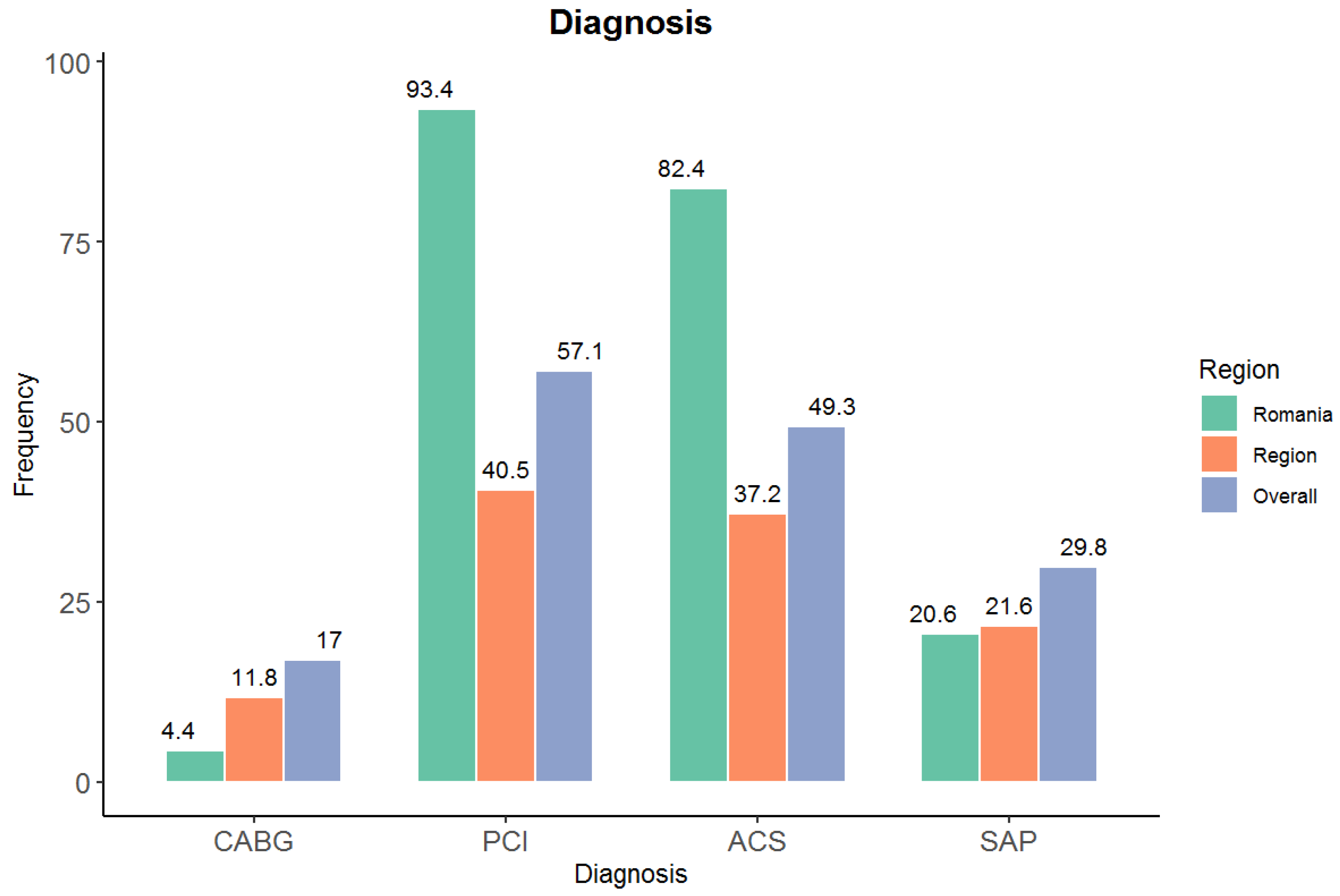

- CABG (Yes): lower in Romania (4.4%) vs. Europe (19.3%); p < 0.001.

- PCI (Yes): higher in Romania (93.4%) vs. Europe (65.2%); p < 0.001.

- Acute coronary syndrome (Yes): higher in Romania (82.4%) vs. Europe (42.9%); p < 0.001.

- Stable angina (Yes): lower in Romania (20.6%) vs. Europe (35.8%); p < 0.001.

- CHD readmission last year (Yes): lower in Romania (17.6%) vs. Europe (53.7% of non-missing); p < 0.001.

- Age: Romania mean 61.7 vs. Europe 64.9 years; Welch t-test p < 1 × 10−6 (younger in Romania).

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marzà-Florensa, A.; Vaartjes, I.; Graham, I.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Grobbee, D.E.; Joseph, M.; Costa, Y.C.; Enrique, N.E.; Gabulova, R.; Isaveva, M.; et al. A Global Perspective on Cardiovascular Risk Factors by Educational Level in CHD Patients: SURF CHD II. Glob. Heart 2024, 19, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Newby, L.K.; Arnold, S.V.; Bittner, V.; Brewer, L.C.; Demeter, S.H.; Dixon, D.L.; Fearon, W.F.; Hess, B.; Johnson, H.M.; et al. 2023 AHA/ACC/ACCP/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, e59–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotseva, K.; De Bacquer, D.; De Backer, G.; Rydén, L.; Jennings, C.; Gyberg, V.; Abreu, A.; Aguiar, C.; Conde, A.C.; Davletov, K.; et al. Lifestyle and risk factor management in people at high risk of cardiovascular disease: A report from the European Society of Cardiology European Action on Secondary and Primary Prevention by Intervention to Reduce Events (EUROASPIRE) IV cross-sectional survey in 14 European regions. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 2007–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Back, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies with the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/multisociety guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2019, 139, e1082–e1143. [Google Scholar]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; D’Agostino, M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023: Protect People from Tobacco Smoke; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240077164 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Babb, S.; Malarcher, A.; Schauer, G.; Asman, K.; Jamal, A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000–2015. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 65, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, K.E.; Paluch, A.E.; Blair, S.N. Physical activity for health: What kind? How much? How intense? On top of what? Annu. Rev. Public Health 2011, 32, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240015128 (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekelund, U.; Tarp, J.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Hansen, B.H.; Jefferis, B.; Fagerland, M.W.; Whincup, P.; Diaz, K.M.; Hooker, S.P.; Chernofsky, A.; et al. Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. BMJ 2019, 366, l4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayıroğlu, M.İ. Telemedicine: Current Concepts and Future Perceptions. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2019, 22 (Suppl. S2), 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalidis, I.; Lu, H.; Maurizi, N.; Fournier, S.; Tsigkas, G.; Apostolos, A.; Cook, S.; Iglesias, J.F.; Garot, P.; Hovasse, T.; et al. Mobile Health Applications for Secondary Prevention After Myocardial Infarction or PCI: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chooi, Y.C.; Ding, C.; Magkos, F. The epidemiology of obesity. Metabolism 2019, 92, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.D.; Ryan, D.H.; Apovian, C.M.; Ard, J.D.; Comuzzie, A.G.; Donato, K.A.; Hu, F.B.; Hubbard, V.S.; Jakicic, J.M.; Kushner, R.F.; et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2014, 129 (Suppl. S2), S102–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Oldridge, N.; Thompson, D.R.; Zwisler, A.D.; Rees, K.; Martin, N.; Taylor, R.S. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD001800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, N.H.; Shaw, J.E.; Karuranga, S.; Huang, Y.; da Rocha Fernandes, J.D.; Ohlrogge, A.W.; Malanda, B. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 138, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Sarwar, N.; Gao, P.; Seshasai, S.R.; Gobin, R.; Kaptoge, S.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Ingelsson, E.; Lawlor, D.A.; Selvin, E.; et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010, 375, 2215–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.J.; Peters, J.R.; Tynan, A.; Evans, M.; Heine, R.J.; Bracco, O.L.; Zagar, T.; Poole, C.D. Survival as a function of HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2010, 375, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cosentino, F.; Grant, P.J.; Aboyans, V.; Bailey, C.J.; Ceriello, A.; Delgado, V.; Federici, M.; Filippatos, G.; Grobbee, D.E.; Hansen, T.B.; et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 255–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seshasai, S.R.; Kaptoge, S.; Thompson, A.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Gao, P.; Sarwar, N.; Whincup, P.H.; Mukamal, K.J.; Gillum, R.F.; Holme, I.; et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 829–841. [Google Scholar]

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998, 352, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewington, S.; Clarke, R.; Qizilbash, N.; Peto, R.; Collins, R.; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: A meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002, 360, 1903–1913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bundy, J.D.; Li, C.; Stuchlik, P.; Bu, X.; Kelly, T.N.; Mills, K.T.; He, H.; Chen, J.; Whelton, P.K.; He, J. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelton, P.K.; Carey, R.M.; Aronow, W.S.; Casey, D.E., Jr.; Collins, K.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; DePalma, S.M.; Gidding, S.; Jamerson, K.A.; Jones, D.W.; et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, e127–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Romania | Europe | |

| (N = 136) | (N = 3586) | |

| Male | 110 (80.9%) | 2627 (73.3%) |

| Mean Age (SD) | 61.7 (10.9) | 64.9 (10.7) |

| Median [Min, Max] | 63.0 [28.0, 84.0] | 65.0 [27.0, 99.0] |

| CABG | 6 (4.4%) | 693 (19.3%) |

| PCI | 127 (93.4%) | 2338 (65.2%) |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome | 112 (82.4%) | 1539 (42.9%) |

| Stable Angina Pectoris | 28 (20.6%) | 1285 (35.8%) |

| CHD hospital admission in the last year | ||

| Yes | 24 (17.6%) | 1900 (53.0%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 47 (1.3%) |

| 3 (0.1%) |

| Variable | Romania n/N (%) | Europe n/N (%) | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex | 110/136 (80.9%) | 2627/3585 (73.3%) | 7.6% [0.1%, 15.2%] | 1.10 [1.01, 1.20] | 1.54 [1.00, 2.38] | 1.97 | 0.048 |

| CABG (Yes) | 6/136 (4.4%) | 693/3586 (19.3%) | −14.9% [−21.6%, −8.2%] | 0.23 [0.10, 0.50] | 0.19 [0.08, 0.44] | −4.37 | 1.24 × 10−5 |

| PCI (Yes) | 127/136 (93.4%) | 2338/3586 (65.2%) | 28.2% [20.1%, 36.3%] | 1.43 [1.36, 1.51] | 7.53 [3.82, 14.86] | 6.82 | 8.99 × 10−12 |

| Acute Coronary Syndrome (Yes) | 112/136 (82.4%) | 1539/3586 (42.9%) | 39.4% [30.9%, 47.9%] | 1.92 [1.76, 2.09] | 6.21 [3.97, 9.69] | 9.09 | 1.02 × 10−19 |

| Stable Angina Pectoris (Yes) | 28/136 (20.6%) | 1285/3585 (35.8%) | −15.2% [−23.4%, −7.1%] | 0.57 [0.41, 0.80] | 0.46 [0.30, 0.71] | −3.65 | 2.58 × 10−4 |

| CHD admission last year (Yes) | 24/136 (17.6%) | 1900/3536 (53.7%) | −36.1% [−44.6%, −27.5%] | 0.33 [0.23, 0.47] | 0.18 [0.12, 0.29] | −8.27 | 1.35 × 10−16 |

| Variable | Romania Mean (SD) | Europe Mean (SD) | Mean Difference (RO-EU) | Welch t | df (Approx) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.7 (10.9) | 64.9 (10.7) | −3.2 | −3.36 | ~145 | 9.9 × 10−4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mosteoru, S.; Kundnani, N.R.; Rus, A.; Ilin, S.; Ciocan, V.; Albulescu, N.; Neagu, M.N.; Gaita, L.; Gaita, D. Importance of Secondary Prevention in Coronary Heart Disease. Medicina 2025, 61, 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112011

Mosteoru S, Kundnani NR, Rus A, Ilin S, Ciocan V, Albulescu N, Neagu MN, Gaita L, Gaita D. Importance of Secondary Prevention in Coronary Heart Disease. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112011

Chicago/Turabian StyleMosteoru, Svetlana, Nilima Rajpal Kundnani, Andreea Rus, Simona Ilin, Veronica Ciocan, Nicolae Albulescu, Marioara Nicula Neagu, Laura Gaita, and Dan Gaita. 2025. "Importance of Secondary Prevention in Coronary Heart Disease" Medicina 61, no. 11: 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112011

APA StyleMosteoru, S., Kundnani, N. R., Rus, A., Ilin, S., Ciocan, V., Albulescu, N., Neagu, M. N., Gaita, L., & Gaita, D. (2025). Importance of Secondary Prevention in Coronary Heart Disease. Medicina, 61(11), 2011. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112011