Prognostic Value of Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systemic Involvement and Prognostic Complexity

1.2. Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis: Principles, Clinical Relevance and Diagnostic Potential

1.3. Rationale: Prognostic Value of MF-BIA in COPD

1.4. Objectives

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: Adult patients (≥18 years) diagnosed with COPD, based on accepted international guidelines (e.g., GOLD). Studies with mixed populations were included only if COPD-specific results were reported separately.

- Intervention: Use of MF-BIA to assess body composition. Studies using BIA without explicit frequency specification were eligible only if BIA-derived parameters were clearly central to the prognostic model. Studies using SF-BIA were excluded.

- Comparators: Not required for eligibility. Both single-arm and comparative studies were included.

- Outcomes: Studies were required to report prognostic endpoints associated with BIA parameters, including all-cause mortality, survival, frequency of exacerbations, or hospital readmissions.

- Study design: Eligible studies included observational (prospective or retrospective cohort, case–control) and interventional studies. Reviews, meta-analyses, editorials, opinion pieces, conference abstracts without full text, and studies with insufficient methodological quality were excluded.

- Language: No language restrictions were applied; full texts were evaluated directly or via assisted translation.

- Publication date: No restrictions by year of publication; studies indexed up to 29 April 2025 were eligible.

- Citation tracking: Backward and forward citation tracking was not applied.

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search Strategy

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: “COPD”, “chronic obstructive pulmonary disease”.

- Bioelectrical impedance analysis: “bioimpedance”, “bioelectrical impedance”, “BIA”, “multifrequency bioimpedance”, “multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance”.

- Prognostic relevance: “prognosis”, “prognostic”, “outcome”, “mortality”, “survival”.

2.5. Selection Process

2.6. Data Collection Process

2.7. Data Items

- Study identification: first author, year of publication and country.

- Study characteristics: study design, sample size and follow-up duration.

- Population details: baseline characteristics and relevant cardiac comorbidities, where available.

- BIA-related information: device used and BIA parameters.

- Prognostic outcomes: mortality, exacerbation rates, hospitalizations, or composite endpoints. All reported results that were compatible with these outcome domains were sought, regardless of time point or statistical model.

- Statistical analysis: effect measures, covariates used in multivariate models, confidence intervals.

- Key findings: main conclusions regarding the prognostic relevance of MF-BIA parameters.

2.8. Risk of Bias Assessment

2.9. Effect Measures

- For time-to-event outcomes (e.g., mortality, survival), hazard ratios were preferred when available.

- For dichotomous outcomes, odds ratios or relative risks were recorded.

- For continuous outcomes, mean differences or standardized mean differences were noted.

2.10. Synthesis Methods

2.11. Reporting Bias Assessment

2.12. Certainty Assessment

2.13. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

3. Results

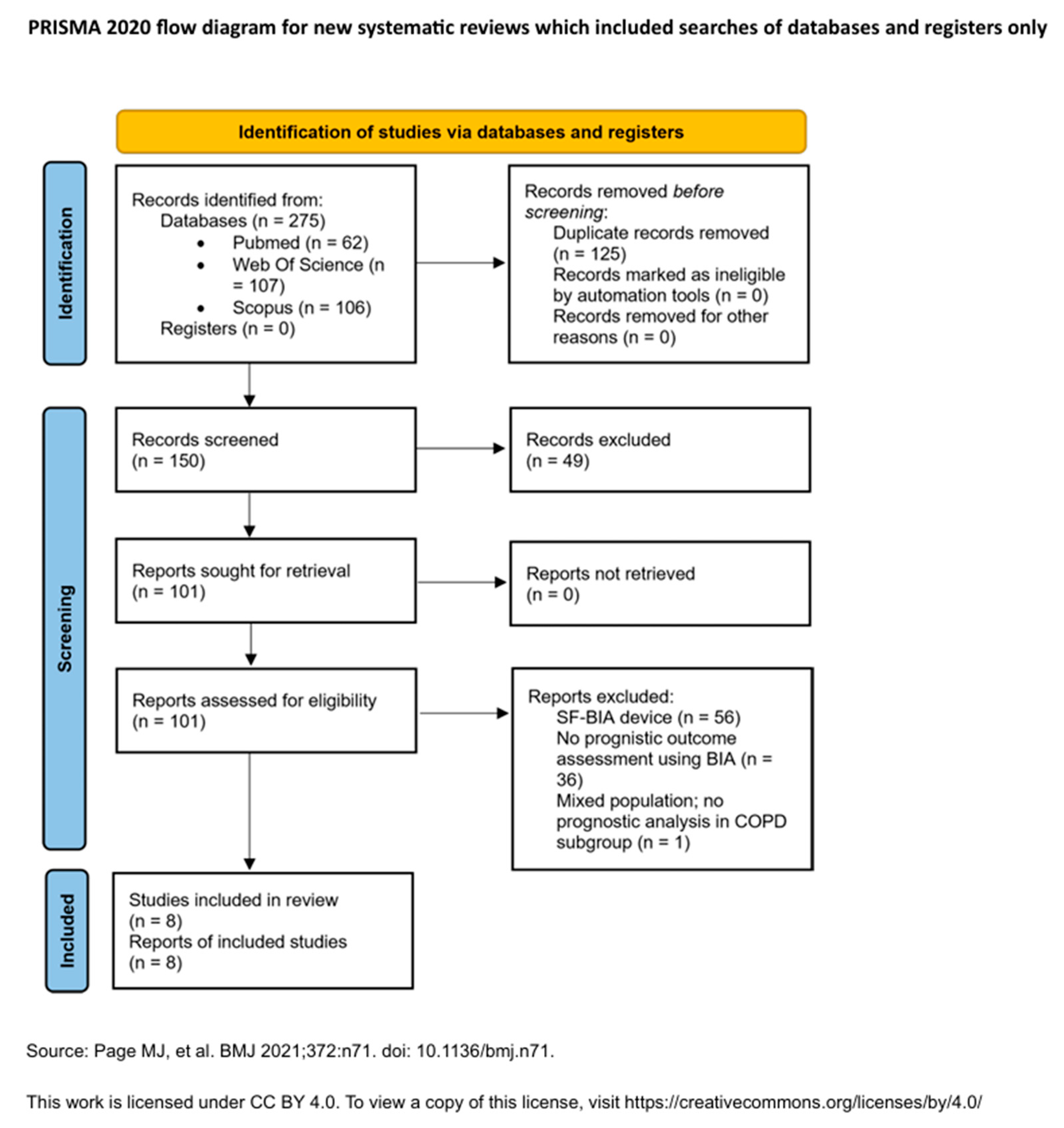

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

- ECW/TBW (1 study) [29].

- Hospitalizations, emergency visits, and pneumonia incidence (in multicenter or longitudinal studies).

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Individual Studies

3.5. Synthesis of Results

3.5.1. Mortality

3.5.2. Exacerbations and Hospitalizations

3.5.3. Functional or Composite Outcomes

3.6. Reporting Biases

3.7. Certainty of Evidence

- Use of validated clinical endpoints (e.g., mortality, exacerbations).

- Consistent findings for PhA and FFMI across multiple studies.

- Application of multivariate statistical models in most analyses.

- Methodological heterogeneity.

- Incomplete adjustment for confounders such as comorbidities.

- Small sample sizes and absence of standardized outcome definitions in several studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Implications for Practice

- Standardizing methodology, including device calibration, patient posture, and frequency selection

- Defining validated cutoffs for PhA, FFMI, and ECW%, tailored to COPD populations

- Integrating comorbidities and biomarkers (e.g., NT-proBNP) into prognostic models

- Assessing longitudinal changes in BIA parameters following rehabilitation, nutrition, or diuretic therapy

- Incorporating BIA into composite risk scores and exploring advanced tools such as segmental BIA and machine learning-based phenotyping

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AE | Acute Exacerbation |

| ASMI | Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass |

| ASMMI | Appendicular Skeletal Muscle Mass Index |

| BCM | Body Cell Mass |

| BFM | Body Fat Mass |

| BIA | Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| BMC | Bone Mineral Content |

| BODE | Body mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise capacity index |

| CAR | CRP-to-albumin ratio |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| DXA | Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| ECW | Extracellular Water |

| ECW/ICW | Extracellular Water/Intracellular Water Ratio |

| ECW/TBW | Extracellular Water/Total Body Water Ratio |

| FEV1 | Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second |

| FFM | Fat-Free Mass |

| FFMI | Fat-Free Mass Index |

| FM | Fat Mass |

| FMI | Fat Mass Index |

| GDF-15 | Growth Differentiation Factor-15 |

| HfpEF | Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| ICW | Intracellular Water |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 | Interleukin-8 |

| IR | Impedance Ratio |

| MCR | Motoric Cognitive Risk |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MF-BIA | Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte Ratio |

| NOS | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type Natriuretic Peptide |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| PBF | Percent Body Fat |

| PhA | Phase Angle |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RR | Relative Risk |

| SAA | Serum Amyloid A |

| SF-BIA | Single-Frequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis |

| SMI | Skeletal Muscle Index |

| SLM | Soft Lean Mass |

| SMM | Skeletal Muscle Mass |

| TBW | Total Body Water |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

| VFA | Visceral Fat Area |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Search Strategies

- Scopus:

- Web of Science:

- PubMed:

Appendix A.2. Data Extraction Forms

| Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Follow-Up Duration | Baseline Characteristics | Device | BIA Parameters | Prognostic Outcome | Key Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Appendix A.3. Risk of Bias Assessment Tools

| Author | Year | Study Design | Tool Used | Score | Level of Bias | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi et al. [28] | 2024 | Prospective cohort | Newcastle–Ottawa | 7.5 | Low | Clear follow-up and objective outcomes; limited by single-center, small all-male sample (external validity). |

| Xie et al. [29] | 2024 | Cross-sectional with logistic regression | Newcastle–Ottawa | 5.5 | Moderate | Retrospective outcome: logistic regression applied. Sample small and male-only. |

| Gomez-Martinez et al. [34] | 2023 | Prospective cohort | Newcastle–Ottawa | 9 | Low | Well-defined prospective cohort with standardized BIA, mortality outcome, and low bias risk. |

| Choi et al. [30] | 2023 | Retrospective cohort (multicenter) | Newcastle–Ottawa | 7 | Moderate | Multicenter retrospective cohort: outcome and follow-up clearly defined. Device variability not controlled. |

| Karanikas et al. [31] | 2021 | Prospective cohort | Newcastle–Ottawa | 8 | Low | Prospective study with multifrequency BIA and valid AE-COPD outcome; sample small but protocol clearly reported. |

| De Blasio et al. [32] | 2019 | Prospective cohort | Newcastle–Ottawa | 8 | Low | Prospective design with standardized BIA and adjusted analyses; single center and low event count are limitations. |

| Rodrigues et al. [35] | 2018 | Retrospective cohort | Newcastle–Ottawa | 7 | Moderate | Retrospective with validated mortality outcome; device not reported, and model lacks external validation. |

| Maddocks et al. [33] | 2015 | Prospective observational | Newcastle–Ottawa | 8 | Low | Large prospective cohort, standardized BIA; follow-up timing unclear, but outcome data robust. |

Appendix A.4. Summary of Findings from Included Studies

| Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size (n=) | Follow-Up Duration | Baseline Characteristics | Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi et al. [28] | 2024 | Japan | Prospective observational cohort study | 108 | 3 years (median 1082 days) | Male patients with stable COPD. Mean values: age (years) 75.1 ± 7.9, BMI (Kg/m2) 22.7 ± 3.5, FEV1 (liters) 1.46 ± 0.58, FEV1% pred. 55.7 ± 20.7. GOLD stage (%): I 16.7, II 56.7, III 20, IV 6.7. Comorbidities: cardiovascular disease 20.4%. | InBody S10 |

| Xie et al. [29] | 2024 | China | Cross-sectional study with prognostic stratification via logistic regression | 159 | 1 year (retrospective) | Male patients (77 AE-COPD, 82 stable COPD). Mean values in AE-COPD: age (years) 67 ± 8.8, BMI (kg/m2) 18.6 ± 3.4, CAT 21. Mean values in stable COPD: age (years) 62.9 ± 8.3, BMI (kg/m2) 21.4 ± 4.1, CAT 13.5. | InBody S10 |

| Gomez-Martinez et al. [34] | 2023 | Mexico | Prospective cohort study | 240 | 7 years (mean 6.66 years) | 51% male. Mean age (years) 72.3 ± 8.2, BMI (kg/m2) 28.4 ± 7.4, FEV1 (liters) 1.26 ± 0.63, FEV1 (%) 57.61 ± 23.55, GOLD stage (%) I and II 60.18, III and IV 39.82. Comorbidities: heart failure 42.08%. | BodyStat QuadScan 4000 |

| Choi et al. [30] | 2023 | South Korea | Retrospective cohort (multicenter) | 253 | 10 years (median 3.3 years) | 74.7% male. Mean: age (years) 71.0, BMI (kg/m2) 22.8 (20.4–25.0). Comorbidities: heart failure 31.6%. | Not reported |

| Karanikas et al. [31] | 2021 | Greece | Prospective observational cohort study | 76 | 12 months | 50% male. Without AE (n = 25): FEV1 (%) 62.6 ± 20.9. With AE (n = 51): FEV1 (%) 48.5 ± 17.4. | InBody S10 |

| De Blasio et al. [32] | 2019 | Italy | Prospective cohort study | 210 | 24 months | 69% male. Survivors: mean age 68.9 ± 8, BMI 26.2 ± 5.4, FEV1 (%) 41 ± 16, GOLD-IV (%) 29.3; Non-survivers: mean age 72.4 ± 8.3, BMI 23.8 ± 6.4, FEV1 (%) 36 ± 23.9, GOLD-IV (%) 51.7. | Human IM-Touch |

| Rodrigues et al. [35] | 2018 | Brazil | Retrospective cohort | 141 | 24 months | 56% male. Mean: age 70 ± 8, BMI (kg/m2) 24.6, FEV1 (%) 42 ± 17. | Not reported |

| Maddocks et al. [33] | 2015 | United Kingdom | Prospective observational | 502 | Follow-up: 90 days (mortality outcome); median cohort follow-up: 469 days | Stable COPD. 58.7% male. Median: age (years) 71, BMI (kg/m2) 24.7, FEV1 (%) 45. | BodyStat QuadScan 4000 |

| Author (Year) | BIA Parameters | Prognostic Outcome | Key Results | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi et al. (2024) [28] | Segmental PhA (mean values): PhA-RA (4.96 ± 0.73), PhA-LA (4.92 ± 0.73), Ph-RL (4.61 ± 1.10), PhA-LL (4.44 ± 1.06), PhA-TR (5.04 ± 1.07). Whole-body PhA (4.83 ± 0.82). | Severe exacerbation of COPD (hospitalization/emergency department visit) | Low PhA for RL (HR = 3.50, 95% CI 1.33–9.20, p= 0.010), LL (HR = 3.26, 95% CI 1.18–9.04, p = 0.023) and LA (HR = 2.61, 95% CI 1.17–5.8, p = 0.020) were significant predictors for severe exacerbations (adjusted for age, FEV1% pred, CAT score, history of severe exacerbations in the past year). Whole-body PhA and trunk PhA were not significant. RL PhA had the best predictive performance (AUC = 0.73, 95% CI 0.64–0.82), followed by LL (AUC = 0.71, 95% CI 0.62–0.81). Cut-off values of PhA for predicting severe exacerbations: RL 4.5°, LL 4.5°, RA 5.0°. | Segmental PhA in the lower limbs may serve as a noninvasive prognostic marker for severe COPD exacerbations in male patients. |

| Xie et al. (2024) [29] | SMI (Kg/m2), FFMI (kg/m2), FMI (kg/m2), PBF (%), ECW/ICW, PhA (°). | Exacerbation phenotype (frequent vs. infrequent). | Lower PhA was associated with reduced odds of being a frequent exacerbator (OR = 0.396, C95% CI 0.164–0.957, p = 0.040), while higher ECW/TBW increased the odds (OR = 1.086, (5% CI 1.010–1.168, p = 0.026). Cut-off values: PhA < 4.85° (AUC = 0.753, 95% CI 0.624–0.882), ECW/TBW > 0.393 (AUC= 0.744, 95 %CI 0.611–0.876). | PhA and ECW/TBW may serve as noninvasive markers for exacerbation risk stratification in COPD. |

| Gomez-Martinez et al. (2023) [34] | Mean values: FFMI (kg/m2) 16.62 ± 3.42, IR 0.83, TBW (%) 51.64 ± 8.17, ECW (%) 27.77 ± 6.03, PhA 5.05 ± 0.96 | All-cause mortality | PhA (per degree) was protective (HR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.37–0.94, p = 0.026). PhA < 50th percentile associated with increased mortality risk (HR = 3.47, 95% CI 1.45–8.29, p = 0.005). Sarcopenia (HR = 2.10, 95% CI 1.02–4.33, p = 0.043) was also associated with higher mortality. IR was not significant in multivariate analysis. | PhA and functional indicators of muscle mass may serve as independent prognostic markers of all-cause mortality in COPD. |

| Choi et al. (2023) [30] | FMI (kg/m2) 6.0 (4.5–8.0), FFMI (kg/m2) 16.4 ± 2.2, SMI (kg/m2) 14.2 (12.7–15.5). | AE-COPD, pneumonia development, outpatient/ER visits, (within 1 year). All-cause in hospital mortality. | Low TSMI—independently associated with acute exacerbations (HR = 0.200, 95% CI 0.048–0.838, p = 0.028). | Low muscle mass, particularly low TSMI, is associated with increased risk of exacerbation. |

| Karanikas et al. (2021) [31] | FFM (kg), FFMI (kg/m2), PhA, BFM (%). | COPD acute exacerbation | In multivariate logistic regression (Model 1, adjusted for age, sex, and smoking index): FFM (OR = 0.876, 95% CI: 0.790–0.971, p = 0.012), FFMI (OR = 0.671, 95% CI: 0.502–0.897, p = 0.007) were significantly associated with a lower risk of acute COPD exacerbation within one year. | Associations lost significance after adjusting for prior AE; not independent prognostic factors. |

| De Blasio et al. (2019) [32] | FFM (Survivors 46.8 ± 8.5, non-survivors 43.2 ± 9.2, p = 0.031), FFMI, PhA (Survivors 5.2 ± 1.2, non-survivors 4.3 ± 1.2, p < 0.001). | 2-year all-cause mortality | Cox regression model 3: PhA (B = −0.63, HR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.36–0.77, p < 0.001); 50/5 IR (B = 0.30, HR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.14–1.66, p < 0.001); 100/5 IR (B = 0.26, HR = 1.29, 95% CI: 1.30–1.49, p < 0.001); 250/5 IR (B = 0.15, HR = 1.16, 95% CI: 1.03–1.30, p < 0.001); PhA < 4.1° and IR > 0.843 strongly predicted mortality across quintiles. | IR and PhA are strong, independent predictors of mortality in COPD patients. |

| Rodrigues et al. (2018) [35] | FFMI (kg/m2). | 2-year all-cause mortality | Cluster I (worse status, including lower FFMI) had 5.17× higher risk of 2-year mortality (HR = 5.17; 95% CI: 1.7–15.7; p = 0.004). FFMI < 16.7 kg/m2 among cut-offs significantly associated with high mortality risk (AUC = 0.750). | Cluster analysis using FFMI and other known mortality predictors outperformed BODE index in identifying 2-year mortality risk in COPD patients. |

| Maddocks et al. (2015) [33] | PhA (median: 4.7), FFMI (kg/m2). | Mortality | Low PhA associated with higher mortality (8.2% vs. 3.6%, p = 0.02), worse functional scores (ISW, 5STS, 4MGS, QMVC), and higher ADO/iBODE. PhA outperformed FFMI in predicting mortality. | PhA is a stronger functional and prognostic marker than FFMI in stable COPD and may aid in identifying high-risk patients. |

Appendix A.5. Excluded Studies and Reasons for Exclusion

| Author | Year | Title | Reason | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abbatecola et al. | 2014 | Body composition markers in older persons with COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 2 | Ahmadi et al. | 2020 | Fortified whey beverage for improving muscle mass in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A single-blind, randomized clinical trial | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 3 | Alsharaway | 2019 | Pulmonary rehabilitation outcome in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with a different body composition | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 4 | Attaway et al. | 2024 | Muscle loss phenotype in COPD is associated with adverse outcomes in the UK Biobank | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 5 | Boesch et al. | 2024 | Tracking Real-World Physical Activity in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Over One Year: Results from a Monocentric, Prospective, Observational Cohort Study | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 6 | Budweiser et al. | 2008 | Nutritional depletion and its relationship to respiratory impairment in patients with chronic respiratory failure due to COPD or restrictive thoracic diseases | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 7 | Byun et al. | 2017 | Sarcopenia correlates with systemic inflammation in COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 8 | Camargo et al. | 2023 | Impact of Obstructive Sleep Apnea on Cardiac Autonomic Control during the Respiratory Sinus Arrhythmia Maneuver in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 9 | Camillo et al. | 2008 | Heart Rate Variability and Disease Characteristics in Patients with COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 10 | Caro De Miguel et al. | 2009 | Relación entre la masa libre de grasa, la masa muscular, la fuerza de contracción voluntaria máxima del cuádriceps y el test de la marcha de 6 minutos en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 11 | Choi et al. | 2022 | Peak oxygen uptake and respiratory muscle performance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Clinical findings and implications | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 12 | Chua et al. | 2019 | Body composition of Filipino chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients in relation to their lung function, exercise capacity and quality of life | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 13 | Creutzberg et al. | 2003 | Efficacy of nutritional supplementation therapy in depleted patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 14 | De Benedetto et al. | 2018 | Supplementation with Qter® and Creatine improves functional performance in COPD patients on long term oxygen therapy | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 15 | De Blasio et al. | 2017 | Raw BIA variables are predictors of muscle strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 16 | Del Ponte and Marinari | 2007 | Body composition abnormalities in patients with COPD: limitations and intervention | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 17 | Dela Coleta et al. | 2008 | Predictors of first-year survival in patients with advanced COPD treated using long-term oxygen therapy | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 18 | Demircioglu et al. | 2020 | Frequency of sarcopenia and associated outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 19 | Dore et al. | 2000 | Composition corporelle des patients ayand une bronchopneumopathie chronique obstructive—Comparaison de l’impedancemetrie bioelectrique et de l’anthropometrie | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 20 | Eisner et al. | 2007 | Body composition and functional limitation in COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 21 | Faisy et al. | 2000 | Bioelectrical impedance analysis in estimating nutritional status and outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory failure | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 22 | Finamore et al. | 2018 | Validation of exhaled volatile organic compounds analysis using electronic nose as index of COPD severity | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 23 | Franssen et al. | 2004 | Effects of whole-body exercise training on body composition and functional capacity in normal-weight patients with COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 24 | Franssen et al. | 2005 | Limb muscle dysfunction in COPD: Effects of muscle wasting and exercise training | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 25 | Giron et al. | 2009 | Nutritional state during COPD exacerbation: Clinical and prognostic implications | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 26 | Gologanu et al. | 2014 | Body composition in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 27 | Gurgun | 2013 | Effects of nutritional supplementation combined with conventional pulmonary rehabilitation in muscle-wasted chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective, randomized and controlled study | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 28 | Hallin et al. | 2011 | Relation between physical capacity, nutritional status and systemic inflammation in COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 29 | Halytska and Stupnytska | 2023 | Clinical features of asthma-COPD overlap syndrome with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 30 | Hamada et al. | 2024 | Phase angle measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Associations with physical inactivity and frailty | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 31 | Hitzl et al. | 2010 | Nutritional status in patients with chronic respiratory failure receiving home mechanical ventilation: Impact on survival | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 32 | Hopkinson et al. | 2008 | Vitamin D receptor genotypes influence quadriceps strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 33 | Hopkinson et al. | 2007 | A prospective study of decline in fat free mass and skeletal muscle strength in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 34 | Hsu et al. | 2014 | Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) is Useful for Assessing the Nutritional Status of Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Cross-sectional Study | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 35 | Ibrayeva et al. | 2024 | Bioimpedansometry in patients with chronic lung diseases in the context of the pulmonary-cardio-renal continuum | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA; cross-sectional correlations only (based on English abstract, no full-text translation available |

| 36 | Ingadottir et al. | 2018 | Two components of the new ESPEN diagnostic criteria for malnutrition are independent predictors of lung function in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 37 | Joppa et al. | 2016 | Sarcopenic Obesity, Functional Outcomes, and Systemic Inflammation in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 38 | Juarez Morales et al. | 2013 | Anemia en pacientes ingresados por una exacerbación de EPOC. Influencia sobre el pronóstico de la enfermedad | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 39 | Jungblut et al. | 2009 | The effects of physical training on the body composition of patients with copd | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 40 | Kaymaz et al. | 2015 | Comparison of the effects of neuromuscular electrical stimulation and endurance training in patients with severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 41 | Kilduff et al. | 2003 | Clinical relevance of inter-method differences in fat-free mass estimation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 42 | Kobayashi et al. | 2024 | Phase angle as an indicator of physical activity in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 43 | Kurosaki et al. | 2009 | Extent of emphysema on HRCT affects loss of fat-free mass and fat mass in COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 44 | Kyle et al. | 2006 | Body composition in patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 45 | Lima et al. | 2011 | Potentially modifiable predictors of mortality in patients treated with long-term oxygen therapy | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 46 | Luo et al. | 2016 | Fat-free mass index for evaluating the nutritional status and disease severity in COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 47 | Machado et al. | 2023 | Differential Impact of Low Fat-Free Mass in People With COPD Based on BMI Classifications: Results From the COPD and Systemic Consequences-Comorbidities Network | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 48 | Marco et al. | 2019 | Malnutrition according to ESPEN consensus predicts hospitalizations and long-term mortality in rehabilitation patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 49 | Marinari et al. | 2013 | Effects of nutraceutical diet integration, with coenzyme Q10 (Q-Ter multicomposite) and creatine, on dyspnea, exercise tolerance, and quality of life in COPD patients with chronic respiratory failure | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 50 | Martinez-Luna et al. | 2022 | Association between body composition, sarcopenia and pulmonary function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 51 | Maynard-Paquette et al. | 2020 | Ultrasound evaluation of the quadriceps muscle contractile index in patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Relationships with clinical symptoms, disease severity and diaphragm contractility | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 52 | McDonald et al. | 2017 | Chest computed tomography-derived low fat-free mass index and mortality in COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 53 | Mete et al. | 2018 | Prevalence of malnutrition in COPD and its relationship with the parameters related to disease severity | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 54 | Minas et al. | 2011 | The Association of Metabolic Syndrome with Adipose Tissue Hormones and Insulin Resistance in Patients with COPD without Co-morbidities | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 55 | Mijd et al. | 2021 | Composition corporelle des patients atteints de bpco et son impact sur la fonction respiratoire | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 56 | Mogelberg et al. | 2022 | High-protein diet during pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 57 | Monteiro et al. | 2012 | Obesity and Physical Activity in the Daily Life of Patients with COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 58 | Mostert et al. | 2000 | Tissue depletion and health related quality of life in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 59 | Muller et al. | 2006 | Assessment of body composition of patients with COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 60 | Mursic et al. | 2024 | Body composition, pulmonary function tests, exercise capacity, and quality of life in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with obesity | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 61 | Naranjo-Hernandez et al. | 2024 | Smart Bioimpedance Device for the Assessment of Peripheral Muscles in Patients with COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 62 | Nezu et al. | 2001 | The effect of nutritional status on morbidity in COPD patients undergoing bilateral lung reduction surgery | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 63 | Norden et al. | 2015 | Nutrition impact symptoms and body composition in patients with COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 64 | Ogasawara et al. | 2018 | Effect of eicosapentaenoic acid on prevention of lean body mass depletion in patients with exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective randomized controlled trial | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 65 | Orea-Tejeda et al. | 2022 | The impact of hydration status and fluid distribution on pulmonary function in COPD patients | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 66 | Ovsyannikov et al. | 2019 | Cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and obesity | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 67 | Persson et al. | 2015 | Vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, and longitudinal outcomes in COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 68 | Pison et al. | 2004 | Effects of home pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic respiratory failure and nutritional depletion | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 69 | Ramires et al. | 2012 | Resting energy expenditure and carbohydrate oxidation are higher in elderly patients with COPD: A case–control study | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 70 | Ramirez-Fuentes et al. | 2019 | Ultrasound assessment of rectus femoris muscle in rehabilitation patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease screened for sarcopenia: correlation of muscle size with quadriceps strength and fat-free mass | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 71 | Rodrigues et al. | 2020 | Are the Effects of High-Intensity Exercise Training Different in Patients with COPD Versus COPD + Asthma Overlap? | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 72 | Rubinsztajn et al. | 2015 | Correlation between hyperinflation defined as an elevated RV/TLC ratio and body composition and cytokine profile in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 73 | Rubinsztajn et al. | 2016 | Body composition analysis performed by bioimpedance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 74 | Sabino et al. | 2010 | Nutritional status is related to fat-free mass, exercise capacity and inspiratory strength in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 75 | Saglam et al. | 2013 | Relationship between obesity and respiratory muscle strength, functional capacity, and physical activity level in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 76 | Sanchez et al. | 2011 | Anthropometric midarm measurements can detect systemic fat-free mass depletion in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 77 | Scarlata et al. | 2021 | Association between frailty index, lung function, and major clinical determinants in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 78 | Schols et al. | 2005 | Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 79 | Seymour et al. | 2009 | Ultrasound measurement of rectus femoris cross-sectional area and the relationship with quadriceps strength in COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 80 | Sepulveda Loyola et al. | 2024 | Impact of pre-sarcopenia and sarcopenia on biological and functional outcomes in individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 81 | Slinde et al. | 2005 | Body composition by bioelectrical impedance predicts mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 82 | Souza et al. | 2019 | Inspiratory muscle strength, diaphragmatic mobility, and body composition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 83 | Texeira et al. | 2021 | Low Muscle Mass Is a Predictor of Malnutrition and Prolonged Hospital Stay in Patients With Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Longitudinal Study | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 84 | Thibault et al. | 2010 | Assessment of nutritional status and body composition in patients with COPD: Comparison of several methods | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 85 | Tomita et al. | 2024 | Impact of Energy Malnutrition on Exacerbation Hospitalization in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Retrospective Observational Study | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 86 | Vakhlamov and Tyurikova | 2015 | Rationale for the use of new methods of investigation of metabolic syndrome in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with broncho-obstructive diseases | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 87 | Vestbo et al. | 2006 | Body mass, fat-free body mass, and prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a random population sample: Findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 88 | Waatevik et al. | 2012 | Different COPD characteristics are related to different outcomes in the 6 min walk test | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 89 | Waatevik et al. | 2016 | Oxygen desaturation in 6 min walk test is a risk factor for adverse outcomes in COPD | Single-frequency BIA device |

| 90 | Welch et al. | 2025 | Establishing Predictors of Acute Sarcopenia: A Proof-OfConcept Study Utilising Network Analysis | Mixed population; no prognostic analysis in COPD subgroup |

| 91 | Yogesh et al. | 2024 | The triad of physiological challenges: investigating the intersection of sarcopenia, malnutrition, and malnutrition-sarcopenia syndrome in patients with COPD—a cross-sectional study | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 92 | Yoshikawa and Kanazawa | 2021 | Association of plasma adiponectin levels with cellular hydration state measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis in patients with COPD | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

| 93 | Yoshimura et al. | 2018 | Interdependence of physical inactivity, loss of muscle mass and low dietary intake: Extrapulmonary manifestations in older chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients | No prognostic outcome assessment using BIA |

References

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD: 2023 Report [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Canepa, M.; Franssen, F.; Olschewski, H.; Lainscak, M.; Böhm, M.; Tavazzi, L.; Rosenkranz, S. Diagnostic and therapeutic gaps in patients with heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2019, 7, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.M. Heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Diagnostic pitfalls and epidemiology. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2009, 11, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltais, F.; Decramer, M.; Casaburi, R. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update on limb muscle dysfunction in COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 189, e15–e62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutten, E.P.A. Changes in body composition in patients with COPD: Do they influence patient-related outcomes? Chron. Respir. Dis. 2014, 11, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustí, A.; Edwards, L.D.; Rennard, S.I.; MacNee, W.; Tal-Singer, R.; Miller, B.E.; Vestbo, J.; Lomas, D.A.; Calverley, P.M.; Wouters, E.; et al. Persistent systemic inflammation is associated with poor clinical outcomes in COPD: A novel phenotype. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.H.; Han, M.F.; Teng, X.B.; Shi, J.F.; Xu, X.L. Combined inflammatory markers for predicting acute exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with respiratory failure. J. Inflamm. Res. 2025, 18, 2513–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, T.; Doi, K.; Matsunaga, K.; Takahashi, S.; Donishi, T.; Suga, K.; Oishi, K.; Yasuda, K.; Mimura, Y.; Harada, M.; et al. A novel role of growth differentiation factor (GDF)-15 in overlap with sedentary lifestyle and cognitive risk in COPD. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schols, A.M.W.J. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 82, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.A.; Ionescu, A.A.; Nixon, L.S.; Lewis-Jenkins, V.; Matthews, S.B.; Griffiths, T.L.; Shale, D.J. Inflammatory response and body composition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2001, 164, 1414–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagan, T.M.L.; Aukrust, P.; Ueland, T.; Hardie, J.A.; Johannessen, A.; Mollnes, T.E.; Damås, J.K.; Bakke, P.S.; Wagner, P.D. Body composition and plasma levels of inflammatory biomarkers in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bragança, B.; Moreira, M.; Lopes, R.G.; Campos, I.G.; Ferraro, J.L.; Barbosa, R.; Apolinário, S.; Aguiar, L.; Soares, M.; Silva, P.; et al. Subclinical congestion assessed by whole-body bioelectrical impedance analysis in HFrEF outpatients. Neth. Heart J. 2025, 33, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbrignadello, S.; Göbl, C.; Tura, A. Bioelectrical impedance analysis for the assessment of body composition in sarcopenia and type 2 diabetes. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celli, B.R.; Cote, C.G.; Marin, J.M.; Casanova, C.; Montes de Oca, M.; Mendez, R.A.; Plata, V.P.; Cabral, H.J. The Body-Mass Index, Airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise Capacity Index in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, U.G.; Bosaeus, I.; De Lorenzo, A.D.; Deurenberg, P.; Elia, M.; Gómez, J.M.; Heitmann, B.L.; Kent-Smith, L.; Melchior, J.-C.; Pirlich, M.; et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis—Part I: Review of principles and methods. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 1226–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, D.; Baig, I.; Subbiondo, R.; Iqbal, U. The usefulness of bioelectrical impedance as a marker of fluid status in patients with congestive heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e37377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalin, S.F.; Acar, H.; Kılıç, M.; Şahin, M.; Duman, E. Single-frequency and multi-frequency bioimpedance analysis: What is the difference? Nephrology 2018, 23, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gába, A.; Kapuš, O.; Cuberek, R.; Botek, M.; Kohliková, E.; Přidalová, M. Comparison of multi- and single-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for assessment of body composition in post-menopausal women: Effects of body mass index and accelerometer-determined physical activity. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosy-Westphal, A.; Schautz, B.; Later, W.; Kehayias, J.J.; Gallagher, D.; Müller, M.J. What makes a BIA equation unique? Validity of eight-electrode multifrequency BIA to estimate body composition in a healthy adult population. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67 (Suppl. 1), S14–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K.J.; Siders, W.A.; Johnson, L.K.; Lukaski, H.C. Validity of segmental multiple-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis to estimate body composition of adults across a range of body mass indexes. Nutrition 2009, 25, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looney, D.P.; Schafer, E.A.; Chapman, C.L.; Pryor, R.R.; Potter, A.W.; Roberts, B.M.; Friedl, K.E. Reliability, biological variability, and accuracy of multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analysis for measuring body composition components. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1491931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupertuis, Y.M.; Jimaja, W.; Beardsley Levoy, C.; Genton, L. Bioelectrical impedance analysis instruments: How do they differ, what do we need for clinical assessment? Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2025, 28, 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, K.; Stobäus, N.; Pirlich, M.; Bosy-Westphal, A. Bioelectrical phase angle and impedance vector analysis—Clinical relevance and applicability of impedance parameters. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 31, 854–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.C. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in the assessment of sarcopenia. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2018, 21, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, G.; Shao, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Correlation between body composition and disease severity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1304384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, F.; Marinari, S.; De Blasio, F. Phase angle in assessment and monitoring treatment of individuals with respiratory disease. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2023, 24, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, T.; Murakami, T.; Ono, H.; Togashi, S.; Takahashi, T. Segmental phase angle can predict incidence of severe exacerbation in male patients with COPD. Nutrition 2025, 132, 112681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, A.; Huang, W.; Ko, C. Extracellular Water Ratio and Phase Angle as Predictors of Exacerbation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Adv. Respir. Med. 2024, 92, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J.; Park, H.J.; Cho, J.H.; Byun, M.K. Low Skeletal Muscle Mass and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2023, 86, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikas, I.; Karayiannis, D.; Karachaliou, A.; Papanikolaou, A.; Chourdakis, M.; Kakavas, S. Body composition parameters and functional status test in predicting future acute exacerbation risk among hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5605–5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Blasio, F.; Scalfi, L.; Di Gregorio, A.; Alicante, P.; Bianco, A.; Tantucci, C.; Bellofiore, B.; De Blasio, F. Raw Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis Variables Are Independent Predictors of Early All-Cause Mortality in Patients with COPD. Chest 2019, 155, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, M.; Kon, S.S.C.; Jones, S.E.; Canavan, J.L.; Nolan, C.M.; Higginson, I.J.; Gao, W.; Polkey, M.I.; Man, W.D.C. Bioelectrical impedance phase angle relates to function, disease severity and prognosis in stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Martínez, M.; Rodríguez-García, W.; González-Islas, D.; Orea-Tejeda, A.; Keirns-Davis, C.; Salgado-Fernández, F.; Hernández-López, S.; Jiménez-Valentín, A.; Ríos-Pereda, A.V.; Márquez-Cordero, J.C.; et al. Impact of Body Composition and Sarcopenia on Mortality in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.; Camillo, C.A.; Furlanetto, K.C.; Paes, T.; Morita, A.A.; Spositon, T.; Donaria, L.; Ribeiro, M.; Probst, V.S.; Hernandes, N.A.; et al. Cluster analysis identifying patients with COPD at high risk of 2-year all-cause mortality. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2019, 16, 1479972318809452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faisy, C.; Rabbat, A.; Kouchakji, B.; Laaban, J.P. Bioelectrical impedance analysis in estimating nutritional status and outcome of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acute respiratory failure. Intensive Care Med. 2000, 26, 518–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, P.P.; Kowalski, V.H.; Valduga, K.; de Araújo, B.E.; Silva, F.M. Low Muscle Mass Is a Predictor of Malnutrition and Prolonged Hospital Stay in Patients with Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Longitudinal Study. JPEN J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2021, 45, 1221–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mjid, M.; Snène, H.; Hedhli, A.; Rouhou, S.C.; Toujani, S.; Dhahri, B. COPD patients’ body composition and its impact on lung function. Tunis. Med. 2021, 99, 285–290. [Google Scholar]

| Author and Year | Study Design | Sample | Device | BIA Parameters | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kobayashi et al. 2024 [28] | Prospective observational cohort study | 108, male | InBody S10 | Segmental and whole-body PhA. | Segmental PhA in the lower limbs was associated with the incidence of severe COPD exacerbations in male patients and may serve as a noninvasive prognostic marker for severe COPD exacerbations. |

| Xie et al. 2024 [29] | Cross-sectional study with prognostic stratification via logistic regression. | 159, male | InBody S10 | BCM, BMC, ECW, ECW/ICW, ECW/TBW, FFM, FFMI, FM, FMI, ICW, Mineral, PBF, PhA, Protein, SLM, SMI, SMM, TBW, VFA. | Low PhA and/or high ECW/TBW were associated with frequent exacerbations. They may serve as noninvasive markers for exacerbation frequency in COPD. |

| Gomez-Martinez et al. 2023 [34] | Prospective cohort study | 240, 51% male | BodyStat QuadScan 4000 | ASMMI, ECW, FM, FFMI, IR, PhA, TBW. | PhA below the 50th percentile was independently associated with mortality. PhA may serve as independent prognostic marker of all-cause mortality in COPD. |

| Choi et al. 2023 [30] | Retrospective observational cohort study (multicenter) | 253, 74.7% male | Not specified | ASMI, FMI, FFMI, SMI, TSMI. | Low muscle mass was associated with poor prognosis, particularly low TSMI was significantly associated with increased risk of acute exacerbation. |

| Karanikas et al. 2021 [31] | Prospective observational cohort study | 76, 50% male | InBody S10 | BFM, FFM, FFMI, PhA. | BIA parameters such as FFM and FFMI were associated with the incidence of AE in one year, but associations lost significance after adjusting for prior AE. |

| De Blasio et al. 2019 [32] | Prospective observational cohort study | 210, 69% male | Human IM-Touch analyzer (DS Medica) | FM, FFM, FFMI, IR, PhA. | Higher IR and lower PhA were strong, independent predictors of 2-year all-cause mortality in COPD patients. |

| Rodrigues et al. 2018 [35] | Retrospective cohort | 141, 56% male | Not specified | FFMI. | Cluster analysis using FFMI and other known mortality predictors outperformed BODE index in identifying 2-year mortality risk in COPD patients. |

| Maddocks et al. 2015 [33] | Prospective observational | 502, 58.7% male | BodyStat QuadScan 4000 | FFM, FFMI, PhA. | PhA was a marker of function and disease severity in stable COPD and a possible predictor for mortality. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tiucă, L.-C.; Gheorghe, G.; Ionescu, V.A.; Antonie, N.I.; Diaconu, C.C. Prognostic Value of Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review. Medicina 2025, 61, 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112003

Tiucă L-C, Gheorghe G, Ionescu VA, Antonie NI, Diaconu CC. Prognostic Value of Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112003

Chicago/Turabian StyleTiucă, Loredana-Crista, Gina Gheorghe, Vlad Alexandru Ionescu, Ninel Iacobus Antonie, and Camelia Cristina Diaconu. 2025. "Prognostic Value of Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review" Medicina 61, no. 11: 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112003

APA StyleTiucă, L.-C., Gheorghe, G., Ionescu, V. A., Antonie, N. I., & Diaconu, C. C. (2025). Prognostic Value of Multifrequency Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Systematic Review. Medicina, 61(11), 2003. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61112003