Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia: Impact of Catheterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Variables

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

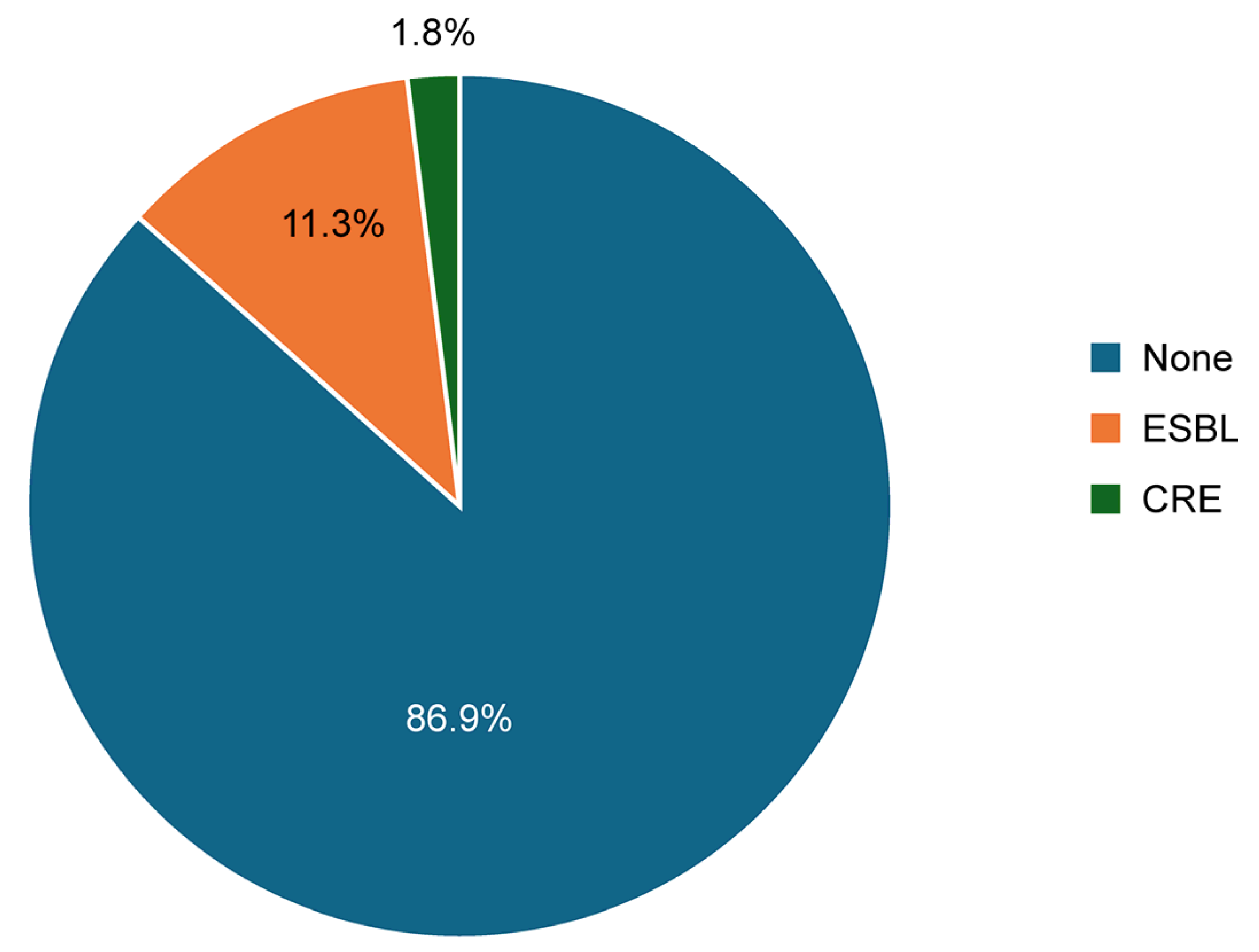

3.1. Overall Prevalence of ESBL and CRE in Enterobacterales Isolates: Comparison Between Catheterized and Non-Catheterized Patients

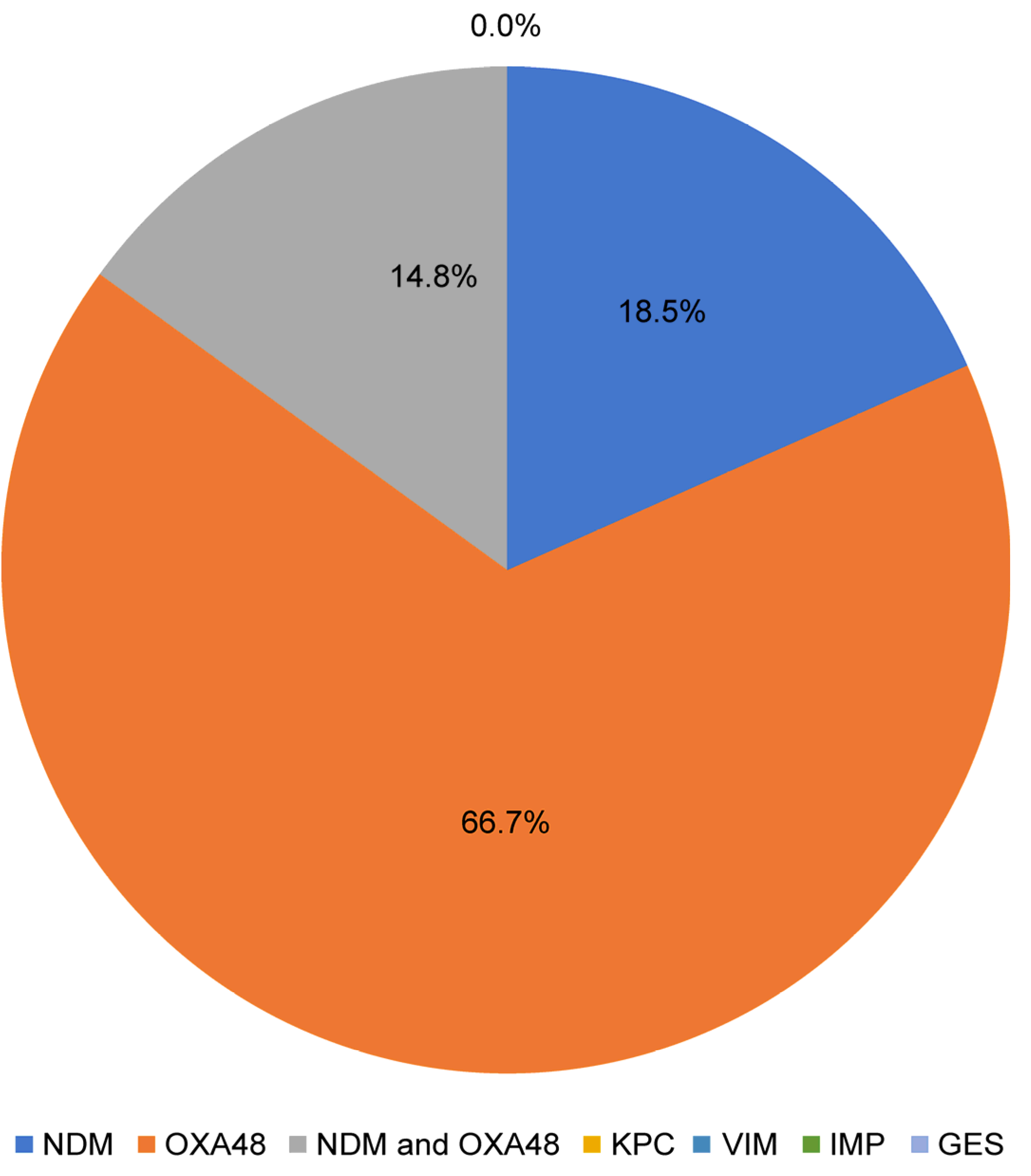

3.2. Predominant Bacterial Species and Distribution and Molecular Resistance Patterns

3.3. Patient Characteristics and Potential Risk Factors for ESBL and CRE Infections

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of ESBL and CRE in Enterobacteriales Isolates and the Impact of Catheterization

4.2. Predominant Bacterial Species and Molecular Resistance Patterns

4.3. Patient Characteristics and Potential Risk Factors for ESBL and CRE Infections

4.4. Summary of Findings: Clinical Implications

4.5. Application

4.6. Limitations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeng, Z.; Zhan, J.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Cheng, S. Global, regional, and national burden of urinary tract infections from 1990 to 2019: An analysis of the global burden of disease study 2019. World J. Urol. 2022, 40, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi, A.H.; Alameer, K.M.; Abuageelah, B.M.; Alharbi, R.H.; Mobarki, M.; Musawi, S.; Haddad, M.; Matabi, A.; Dhayhi, N. Epidemiology and antimicrobial resistance patterns of urinary tract infections: A cross-sectional study from southwestern Saudi Arabia. Medicina 2023, 59, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, L.E. Catheter associated urinary tract infections. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2014, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, V.D.; Yin, R.; Brown, E.C.; Lee, B.H.; Rodrigues, C.; Myatra, S.N.; Kharbanda, M.; Rajhans, P.; Mehta, Y.; Todi, S.K.; et al. Incidence and risk factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infection in 623 intensive care units throughout 37 Asian, African, Eastern European, Latin American, and Middle Eastern nations: Multinational prospective research of INICC. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2024, 45, 567–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougnon, V.; Assogba, P.; Anago, E.; Déguénon, E.; Dapuliga, C.; Agbankpè, J.; Zin, S.; Akotègnon, R.; Moussa, L.B.; Bankolé, H. Enterobacteria responsible for urinary infections: A review about pathogenicity, virulence factors and epidemiology. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokhn, E.S.; Salami, A.; El Roz, A.; Salloum, L.; Bahmad, H.F.; Ghssein, G. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and laboratory profiles of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis isolates as agents of urinary tract infection in Lebanon: Paving the way for better diagnostics. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mireles, A.; Hreha, T.N.; Hunstad, D.A. Pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Top. Spinal Cord. Inj. Rehabil. 2019, 25, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlugu, E.M.; Mohamedi, J.A.; Sangeda, R.Z.; Mwambete, K.D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of uropathogens with biofilm forming capacity among outpatients in Morogoro, Tanzania: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guh, A.Y.; Limbago, B.M.; Kallen, A.J. Epidemiology and prevention of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in the United States. Expert. Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2014, 12, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abalkhail, A.; AlYami, A.S.; Alrashedi, S.F.; Almushayqih, K.M.; Alslamah, T.; Alsalamah, Y.A.; Elbehiry, A. The prevalence of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli producing ESBL among male and female patients with urinary tract infections in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, F.; Iram, S.; Riaz, G.; Rasheed, F.; Shaukat, M. Comparison between non-catheterized and catheter-associated urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae. bioRxiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmare, Z.; Awoke, T.; Genet, C.; Admas, A.; Melese, A.; Mulu, W. Incidence of catheter-associated urinary tract infections by Gram-negative bacilli and their ESBL and carbapenemase production in specialized hospitals of Bahir Dar, northwest Ethiopia. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legese, M.H.; Weldearegay, G.M.; Asrat, D. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase- and carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among Ethiopian children. Infect. Drug Resist. 2017, 10, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natoubi, S.; Barguigua, A.; Diawara, I.; Timinouni, M.; Rakib, K.; Amghar, S.; Zerouali, K. Epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamases and carbapenemases producing Enterobacteriaceae in Morocco. J. Contemp. Clin. Pract. 2020, 6, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. In CLSI guideline M100, 34th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gorgulho, A.; Grilo, A.M.; de Figueiredo, M.; Selada, J. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in a Portuguese hospital: A five-year retrospective study. Germs 2020, 10, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Guo, Z.; Chai, Y.; Fang, Y.P.; Mu, X.; Xiao, N.; Guo, J.; Wang, Z. Risk factors for and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial infections: A retrospective study in a tertiary hospital in Beijing, China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alraddadi, B.M.; Heaphy, E.L.G.; Aljishi, Y.; Ahmed, W.; Eljaaly, K.; Al-Turkistani, H.H.; Alshukairi, A.N.; Qutub, M.O.; Alodini, K.; Alosaimi, R.; et al. Molecular epidemiology and outcome of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.; Mowallad, A.; Mufti, A.; Althaqafi, A.; Jiman-Fatani, A.A.; El-Hossary, D.; Ossenkopp, J.; AlhajHussein, B.; Kaaki, M.; Jawi, N.; et al. Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in western Saudi Arabia and increasing trends in the antimicrobial resistance of Enterobacteriaceae. Cureus 2023, 15, e35050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, I.A.; Alasiri, B.A.; Alkhawajah, M.M.; Shibl, A.M.; Memish, Z.A. The emergence of OXA-48- and NDM-1-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 69, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopotsa, K.; Sekyere, J.O.; Mbelle, N.M. Plasmid evolution in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: A review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1457, 61–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paczosa, M.K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2016, 80, 629–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00001-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, R.; Chakkour, M.; El Dine, H.Z.; Obaseki, E.F.; Obeid, S.T.; Jezzini, A.; Ghssein, G.; Ezzeddine, Z. General Overview of Klebsiella pneumonia: Epidemiology and the Role of Siderophores in Its Pathogenicity. Biology 2024, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.C.; Hung, Y.P.; Lin, W.T.; Dai, W.; Huang, Y.L.; Ko, W.C. Risk factors and clinical impact of bacteremia due to carbapenem-nonsusceptible Enterobacteriaceae: A multicenter study in southern Taiwan. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2021, 54, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Pramanik, A.; Gwinner, T.; Köberle, M.; Bohn, E. Siderophore–drug complexes: Potential medicinal applications of the ‘Trojan horse’ strategy. Microbiology 2009, 155 Pt 9, 2699–2708. [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeddine, Z.; Ghssein, G. Towards new antibiotics classes targeting bacterial metallophores. Microb. Pathog. 2023, 182, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooton, T.M.; Bradley, S.F.; Cardenas, D.D.; Colgan, R.; Geerlings, S.E.; Rice, J.C.; Saint, S.; Schaeffer, A.J.; Tambayh, P.A.; Tenke, P.; et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of catheter-associated urinary tract infection in adults: 2009 International Clinical Practice Guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 50, 625–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | ESBL Specimen Type | p-Value § | CRE Specimen Type | p-Value § | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catheter N (%) (n = 150) | Non-Catheter N (%) (n = 331) | Catheter N (%) (n = 62) | Non-Catheter N (%) (n = 15) | |||

| Age group | ||||||

| ≤45 years | 76 (50.7%) | 194 (58.6%) | 0.104 | 13 (21.0%) | 01 (6.7%) | 0.280 |

| >45 years | 74 (49.3%) | 137 (41.4%) | 49 (79.0%) | 14 (93.3%) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 41 (27.3%) | 68 (20.5%) | 0.099 | 34 (54.8%) | 05 (33.3%) | 0.160 |

| Female | 109 (72.7%) | 263 (79.5%) | 28 (45.2%) | 10 (66.7%) | ||

| Nationality | ||||||

| Saudi | 129 (86.0%) | 281 (84.9%) | 0.751 | 48 (77.4%) | 14 (93.3%) | 0.277 |

| Non-Saudi | 21 (14.0%) | 50 (15.1%) | 14 (22.6%) | 01 (6.7%) | ||

| Type | ||||||

| Emergency | 97 (64.7%) | 229 (69.2%) | <0.001 ** | 13 (21.0%) | 04 (26.7%) | 0.227 |

| Inpatient | 44 (29.3%) | 20 (6.0%) | 47 (75.8%) | 09 (60.0%) | ||

| Outpatient | 09 (6.0%) | 82 (24.8%) | 02 (3.2%) | 02 (13.3%) | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sawan, A.A.; Alghamdi, N.S.; Alzahrani, S.A.; Alharbi, M.S.; Alabdulkareem, N.; Alnufaily, D.A.; Alalwan, S.J.; Mustafa, T.; Alqurashi, M.; El-Badry, A.A. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia: Impact of Catheterization. Medicina 2025, 61, 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111907

Sawan AA, Alghamdi NS, Alzahrani SA, Alharbi MS, Alabdulkareem N, Alnufaily DA, Alalwan SJ, Mustafa T, Alqurashi M, El-Badry AA. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia: Impact of Catheterization. Medicina. 2025; 61(11):1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111907

Chicago/Turabian StyleSawan, Asma Ali, Nada S. Alghamdi, Shahad A. Alzahrani, Muzn S. Alharbi, Nora Alabdulkareem, Dana Ahmed Alnufaily, Sajidah Jaffar Alalwan, Tajammal Mustafa, Maher Alqurashi, and Ayman A. El-Badry. 2025. "Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia: Impact of Catheterization" Medicina 61, no. 11: 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111907

APA StyleSawan, A. A., Alghamdi, N. S., Alzahrani, S. A., Alharbi, M. S., Alabdulkareem, N., Alnufaily, D. A., Alalwan, S. J., Mustafa, T., Alqurashi, M., & El-Badry, A. A. (2025). Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing and Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia: Impact of Catheterization. Medicina, 61(11), 1907. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61111907