Mental Health Among Spanish Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period: A Gender Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Rationale

1.2. COVID-19 Pandemic in Spain

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

- General Health Questionnaire, 12-item version (GHQ-12) [62]. The GHQ-12 is a widely used tool in epidemiological research and a popular measure of psychological distress [63]. It consists of 12 items with several scoring options, two of which were used in this study: the Likert method (0-1-2-3) and the GHQ scoring method (0-0-1-1). The Likert score was used in all analyses, except for discriminating cases with distress from cases without distress, for which the GHQ score was used. According to Lundin et al. [64], the most appropriate threshold for distinguishing cases with distress from cases without distress is ≥ 4. This threshold has a sensitivity of 81.7 and a specificity of 85.4. For the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 when the 12 items were scored using the Likert method and 0.89 when scored using the GHQ scoring method.

- Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) [65]. The SPANE is a 12-item scale in which 6 items assess positive feelings, and 6 items assess negative feelings. Each item is scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (very rarely or never) to 5 (very often or always). The positive and negative scales are scored separately and then combined to measure affect balance. Higher scores indicate that positive feelings are experienced more than negative feelings. For the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were 0.93 for positive feelings, 0.87 for negative feelings, and 0.92 for affect balance.

- Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT) [66]. The term “Thriving denotes the state of positive functioning at its fullest range—mentally, physically, and socially” and the BIT has been designed to measure the core of psychological well-being [66] (p. 256). The scale consists of 10 items with a 5-point Likert response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90 for the current sample.

- Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) [67]. The SWLS is a scale designed to measure global life satisfaction as a cognitive–judgmental process [67]. It consists of 5 items with a 7-point response scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.89.

- Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) [68]. The RSES is a 10-item scale that measures self-esteem and is the most widely used measure of global self-esteem [69]. The response scale is 4-point. It ranges from 0 (strongly disagree) to 3 (strongly agree). In the present study sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.85.

- Social Support Scale (SSS) [70]. This 12-item scale assesses perceived social support and is structured into two factors: emotional social support (7 items) and instrumental social support (5 items). The response scale has five points, ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). For the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 for the emotional social support factor and 0.89 for the instrumental social support factor.

- Stressful Events [39]. Participants were asked if, since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, they had experienced any of the following events and/or losses: (1) loss of employment, (2) financial problems, (3) major disagreement with partner, (4) major disagreement with family, (5) illness of family members or loved ones, (6) death of one or more family members or loved ones, (7) own illness, and (8) other events or losses. During the post-pandemic assessment, participants were asked if they had experienced any of these events in the past year (within the last 12 months). Each event was scored as one point for its presence and zero for its absence. The total number of events was calculated by summing the number of affirmative answers.

- Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) [71]. The BRS is a six-item scale that assess “resilience as the ability to bounce back or recover from stress” [71] (p. 194). The response scale is five points. It ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.81 for the current sample.

- Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Questionnaire (PVD) [72] in the Spanish translation by Díaz et al. [73]. PVD is a 15-item self-report instrument that assesses beliefs about personal susceptibility to infectious disease transmission and emotional discomfort in the presence of potential disease transmission. It has been used in several countries, and data from young adults in 16 countries during the pandemic revealed a global factor associated with the fear of COVID-19 across various levels of threat [74]. The response scale is a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the 15 items was 0.78 for the current sample.

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

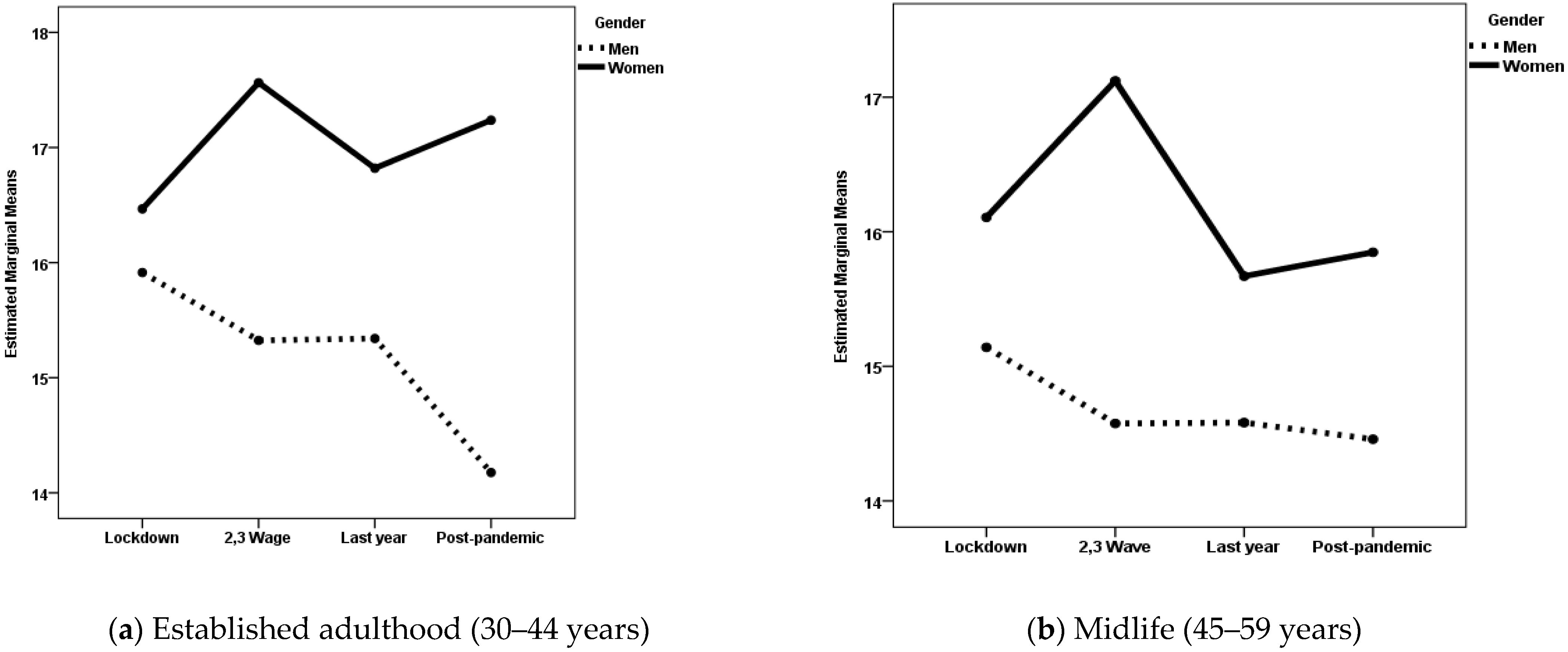

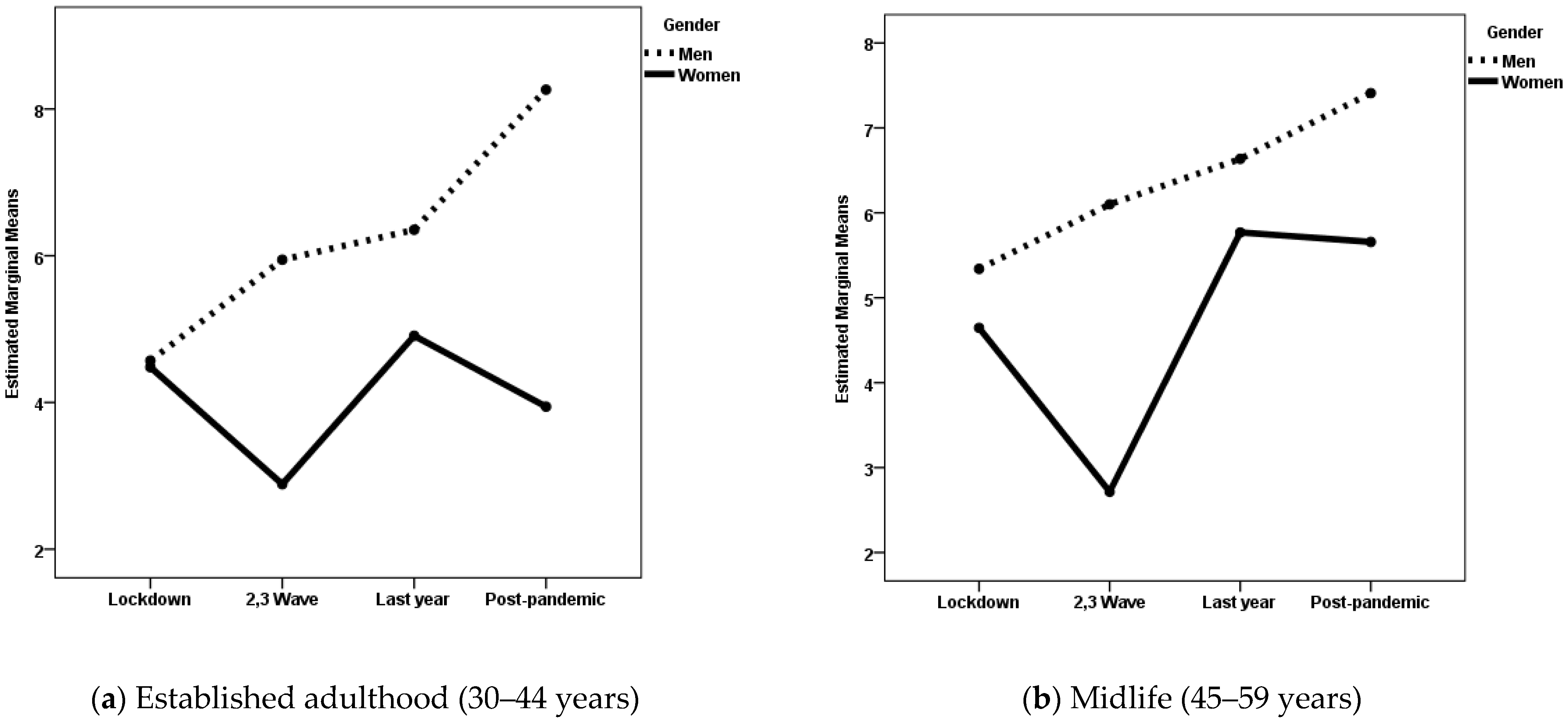

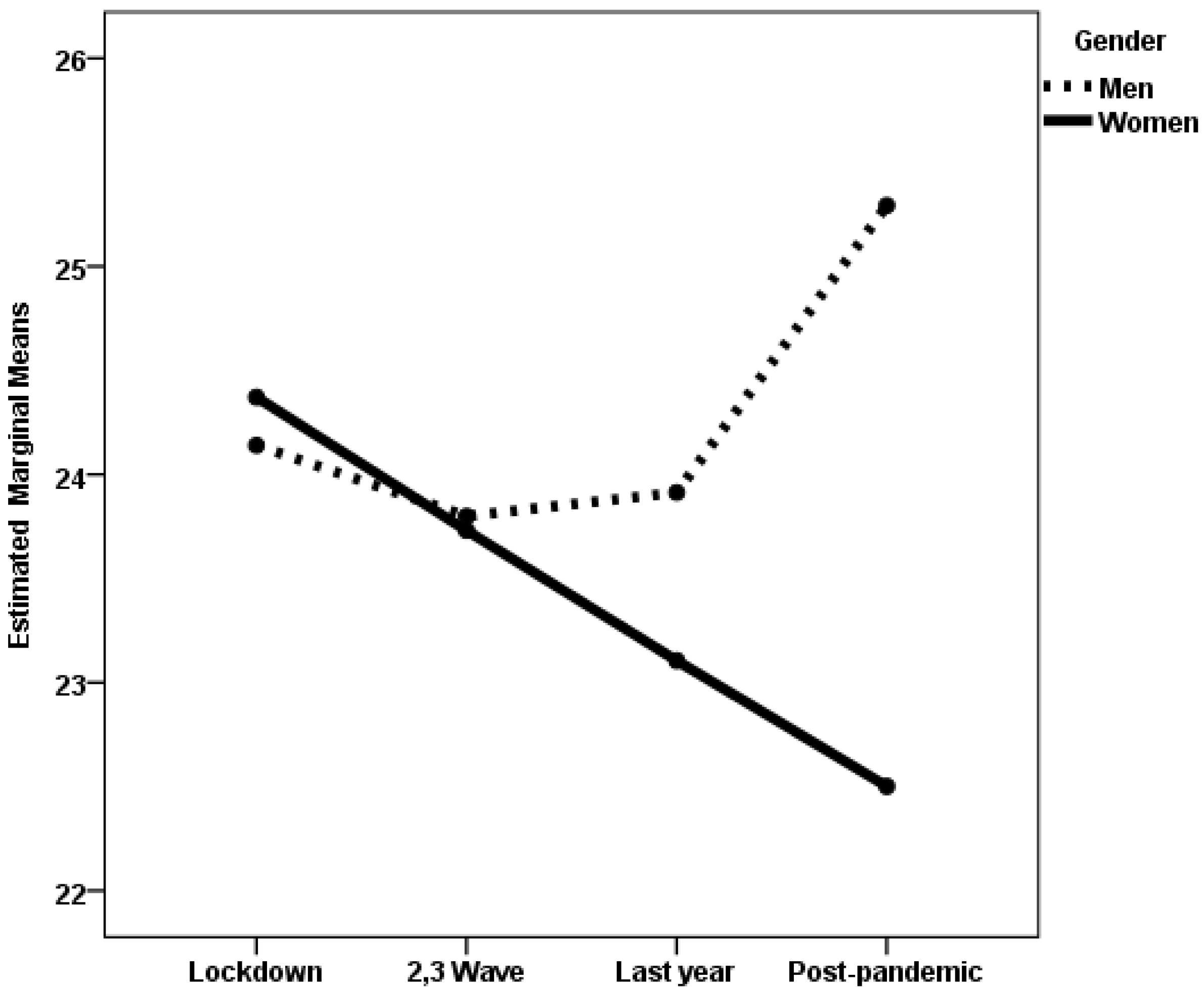

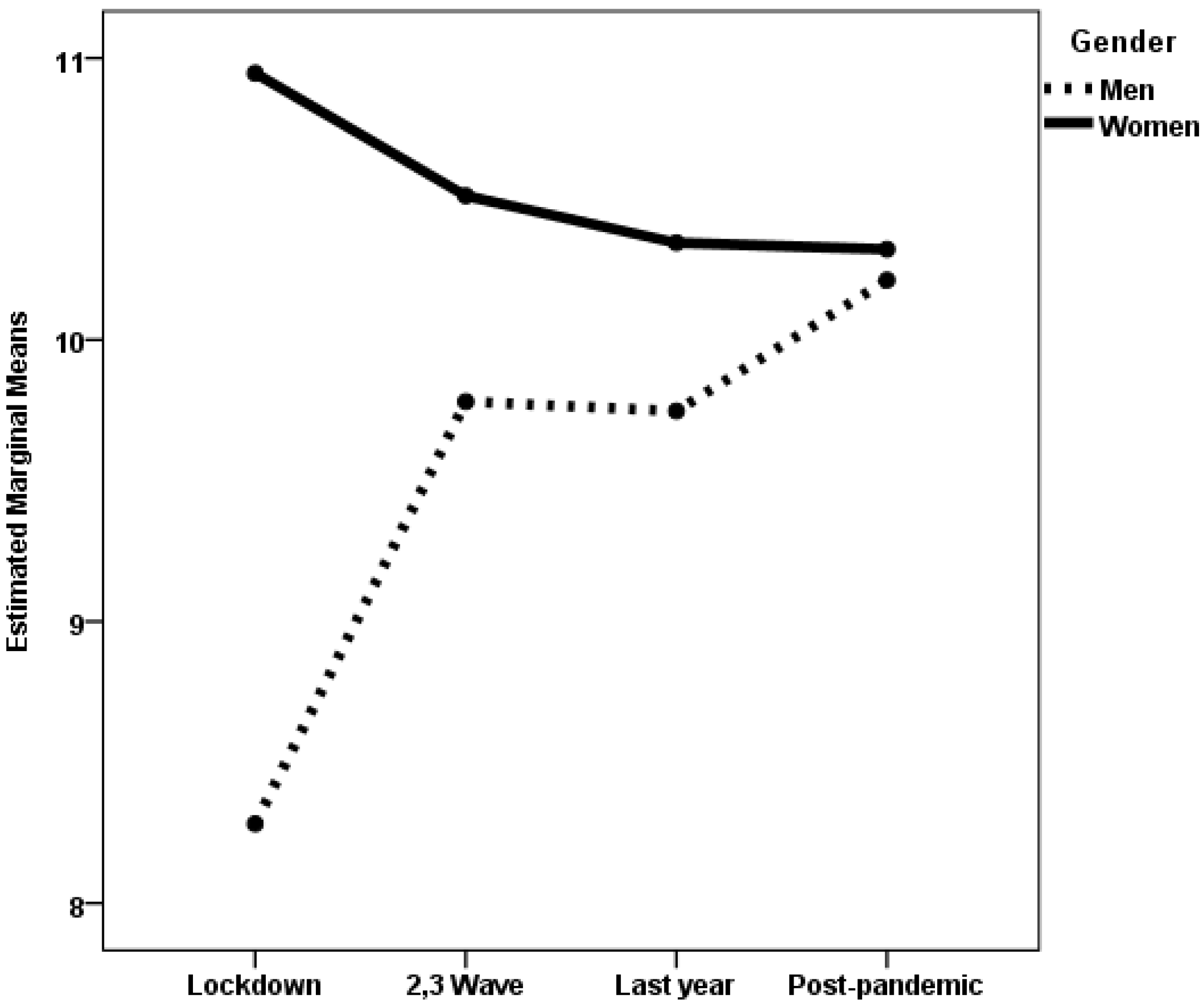

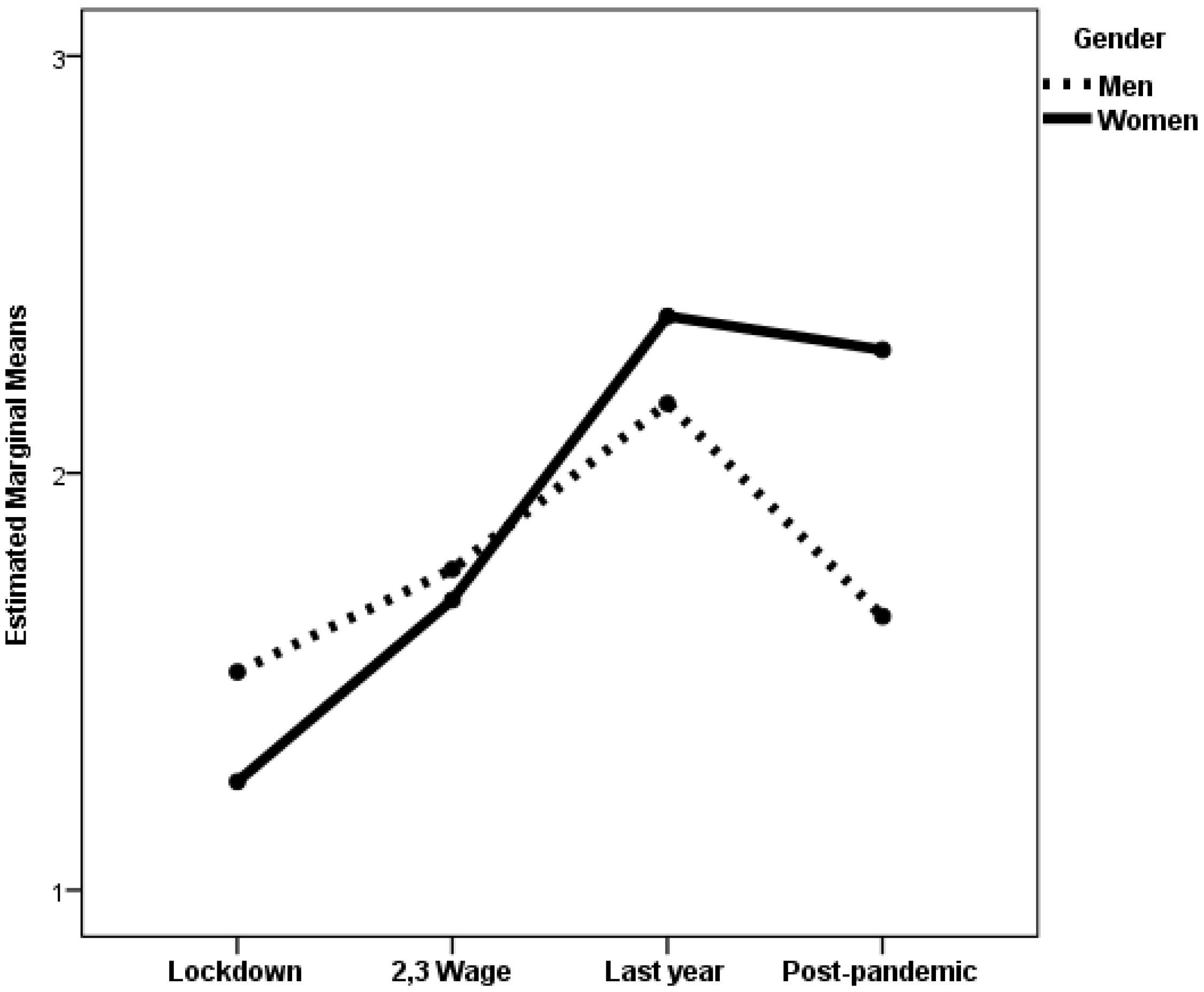

3.1. Differences in Psychological Distress, Well-Being, Social Support, and Stress by Gender and Pandemic Period

3.2. Predictors of Psychological Distress and Well-Being Among Women and Men at Each Life Stage During the Post-Pandemic Period

4. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Cases, World. 2025. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19-11 March 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- World Health Organization. The impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health Cannot be Made Light of. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-mental-health-cannot-be-made-light-of (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Lipsitz, O.; Nasri, F.; Lui, L.M.W.; Gill, H.; Phan, L.; Chen-Li, D.; Iacobucci, M.; Ho, R.; Majeed, A.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aknin, L.B.; De Neve, J.-E.; Dunn, E.W.; Fancourt, D.E.; Goldberg, E.; Helliwell, J.F.; Jones, S.P.; Karam, E.; Layard, R.; Lyubomirsky, S.; et al. Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 17, 915–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Zhou, Y. The COVID-19 Pandemic and its impact on the global economy: What does it take to turn crisis into opportunity? China World Econ. 2020, 28, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyah, Y.; Benjelloun, M.; Lairini, S.; Lahrichi, A. COVID-19 Impact on Public Health, Environment, Human Psychology, Global Socioeconomy, and Education. Sci. World J. 2022, 2022, 5578284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xu, Z.; Skare, M.; Wang, X. The impact of COVID-19 on unemployment dynamics: A panel analysis of youth and gender-specific unemployment in European countries. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2025, 21, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamison, D.T.; Summers, L.H.; Chang, A.Y.; Karlsson, O.; Mao, W.; Norheim, O.F.; Ogbuoji, O.; Schäferhoff, M.; Watkins, D.; Adeyi, O.; et al. Global health 2050: The path to halving premature death by mid-century. Lancet 2024, 404, 1561–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J.J.; Mitra, D. COVID-19 and Americans’ mental health: A persistent crisis, especially for emerging adults 18 to 29. J. Adult Dev. 2024. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Whittingham, M.; Marmarosh, C.L.; Mallow, P.; Scherer, M. Mental health care equity and access: A group therapy solution. Am. Psychol. 2023, 78, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G. Mental health and its psychosocial predictors during national quarantine in Italy against the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Anxiety Stress. Coping 2021, 34, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msherghi, A.; Alsuyihili, A.; Alsoufi, A.; Ashini, A.; Alkshik, Z.; Alshareea, E.; Idheiraj, H.; Nagib, T.; Abusriwel, M.; Mustafa, N.; et al. Mental health consequences of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 605279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieh, C.; Budimir, S.; Humer, E.; Probst, T. Comparing mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown and 6 months after the lockdown in Austria: A longitudinal study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 625973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Hernández, M.E.; Fanjul, L.F.; Díaz-Megolla, A.; Reyes-Hurtado, P.; Herrera-Rodríguez, J.F.; Enjuto-Castellanos, M.d.P.; Peñate, W. COVID-19 lockdown and mental health in a sample population in Spain: The role of self-compassion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams-Prassl, A.; Boneva, T.; Golin, M.; Rauh, C. The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on mental health: Evidence from the United States. Econ. Policy 2022, 37, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Lo Moro, G.; Voglino, G.; Bert, F.; Siliquini, R. Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Fan, S.; Santo, T.D.; Li, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Tasleem, A.; Krishnan, A.; et al. Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ 2023, 380, e074224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyes, B.; McCombe, G.; Broughan, J.; Frawley, T.; Guerandel, A.; Gulati, G.; Kelly, B.D.; Osborne, B.; O’Connor, K.; Cullen, W. Enhancing GP care of mental health disorders post-COVID-19: A scoping review of interventions and outcomes. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2023, 40, 470–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, M.; Zimmerman, L.; Azevedo, K.J.; Ruzek, J.I.; Gala, S.; Magid, H.S.A.; Cohen, N.; Walser, R.; Mahtani, N.D.; Hoggatt, K.J.; et al. Addressing the mental health impact of COVID-19 through population health. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 85, 102006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Awiphan, R.; Phosuya, C.; Ruanta, Y.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Sutin, A.R.; Daly, M.; Jones, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 296, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Longitudinal changes in psychological distress in the UK from 2019 to September 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a large nationally representative study. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Robinson, E. Psychological distress and adaptation to the COVID-19 crisis in the United States. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 136, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, E.; Daly, M. Explaining the rise and fall of psychological distress during the COVID-19 crisis in the United States: Longitudinal evidence from the Understanding America Study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2021, 26, 570–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwong, A.S.F.; Pearson, R.M.; Adams, M.J.; Northstone, K.; Tilling, K.; Smith, D.; Fawns-Ritchie, C.; Bould, H.; Warne, N.; Zammit, S.; et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in two longitudinal UK population cohorts. Br. J. Psychiatry 2021, 218, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamonal-Limcaoco, S.; Montero-Mateos, E.; Lozano-López, M.T.; Maciá-Casas, A.; Matías-Fernández, J.; Roncero, C. Perceived stress in different countries at the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 2022, 57, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, A.B.; Young, S.Y.; Cuijpers, P.; Ayuso-Mateos, J.L.; Barbui, C.; Bertolini, F.; Cabello, M.; Cadorin, C.; Downes, N.; Franzoi, D.; et al. COVID-19 and common mental health symptoms in the early phase of the pandemic: An umbrella review of the evidence. PLoS Med. 2023, 20, e1004206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyland, P.; Shevlin, M.; Murphy, J.; McBride, O.; Fox, R.; Bondjers, K.; Karatzias, T.; Bentall, R.P.; Martinez, A.; Vallières, F. A longitudinal assessment of depression and anxiety in the Republic of Ireland before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.S.; Crivelli, L.; Guimet, N.M.; Allegri, R.F.; Pedreira, M.E. Psychological distress associated with COVID-19 quarantine: Latent profile analysis, outcome prediction and mediation analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchia, M.; Gathier, A.W.; Yapici-Eser, H.; Schmidt, M.V.; de Quervain, D.; van Amelsvoort, T.; Bisson, J.I.; Cryan, J.F.; Howes, O.D.; Pinto, L.; et al. The impact of the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic on stress resilience and mental health: A critical review across waves. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 55, 22–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkire, N.; Nwachukwu, I.; Shalaby, R.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Gusnowski, A.; Surood, S.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Agyapong, V.I.O. COVID-19 pandemic: Influence of relationship status on stress, anxiety, and depression in Canada. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2022, 39, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrens, K.F.; Neumann, R.J.; Kollmann, B.; Brokelmann, J.; von Werthern, N.M.; Malyshau, A.; Weichert, D.; Lutz, B.; Fiebach, C.J.; Wessa, M.; et al. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health in Germany: Longitudinal observation of different mental health trajectories and protective factors. Transl. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, I.; Arora, T.; Thomas, J.; Saneh, A.; Tohme, P.; Abi-Habib, R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Luo, S.; Mu, W.; Li, Y.; Ye, L.; Zheng, X.; Xu, B.; Ding, Y.; Ling, P.; Zhou, M.; et al. Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P.; Zueco, J.; Díaz, A.; Del Pino, M.J.; Fortes, D. Gender differences in mental distress and affect balance during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 21790–21804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matud, M.P.; Del Pino, M.J.; Bethencourt, J.M.; Hernández-Lorenzo, D.E. Stressful events, psychological distress and well-being during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: A gender analysis. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2023, 18, 1291–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, J.; Konaszewski, K.; Skalski, S.; Dobrakowski, P.P.; Muszyńska, J. Resilience and mental health in the Polish Population during the COVID-19 lockdown: A mediation analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Panzeri, A.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Castelnuovo, G.; Mannarini, S. The anxiety-buffer hypothesis in the time of COVID-19: When self-esteem protects from the impact of loneliness and fear on anxiety and depression. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, W.; Su, Y.; Song, Y.; Si, H.; Zhu, L. Death anxiety, self-esteem, and health-related quality of life among geriatric caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychogeriatrics 2022, 22, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, M.M.; Ono, P.; Posada-Villa, S.; Seedat, W. Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 785–795. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinpoor, A.R.; Williams, J.S.; Amin, A.; De Carvalho, I.A.; Beard, J.; Boerma, T.; Kowal, P.; Naidoo, N.; Chatterji, S. Social determinants of self-reported health in women and men: Understanding the role of gender in population health. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heise, L.; Greene, M.E.; Opper, N.; Stavropoulou, M.; Harper, C.; Nascimento, M.; Zewdie, D.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Greene, M.E.; Hawkes, S.; et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: Framing the challenges to health. Lancet 2019, 393, 2440–2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pua, S.Y.; Yu, R.L. Effects of executive function on age-related emotion recognition decline varied by sex. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 361, 117392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, J.; Roth, E.A.; Baird, M.D.; Carman, K.G.; Collins, R.L. A longitudinal study of predictors of serious psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Med. 2023, 53, 2418–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, C.M.; Arnett, J.J.; Palmer, C.G.; Nelson, L.J. Established adulthood: A new conception of ages 30 to 45. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/ (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- United Nations. 2030 Agenda in Lain America and the Caribbean. Goal 5: Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. Available online: https://agenda2030lac.org/en/sdg/5-gender-equality (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- European Institute for Gender Equality. A Better Work–Life Balance: Bridging the Gender Care Gap; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Matud, M.P.; Bethencourt, J.M.; del Pino, M.J.; Hernández-Lorenzo, D.E.; Fortes, D.; Ibánez, I. Time use, health, and well-being across the life cycle: A gender analysis. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, K.; Chaudhari, B.; Ali, T.; Chaudhury, S. Impact of COVID-19 on medical students well-being and psychological distress. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2024, 33, S201–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-García, P.; Hong, S.L.; Bollen, N.; Dellicour, S.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Posada, D. International importance and spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants Alpha, Delta, and Omicron BA.1 into Spain. Commun. Med. 2025, 5, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. The end of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2022, 52, e13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hromić-Jahjefendić, A.; Barh, D.; Uversky, V.; Aljabali, A.A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Alzahrani, K.J.; Alzahrani, F.M.; Alshammeri, S.; Lundstrom, K. Can COVID-19 vaccines induce premature non-communicable diseases: Where are we heading to? Vaccines 2023, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. May 5 Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-pandemic (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Tian, C.; Balmer, L.; Tan, X. COVID-19 lessons to protect populations against future pandemics by implementing PPPM principles in healthcare. EPMA J. 2023, 14, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, V.; Ganado-Pinilla, P.; Sanchez-Santos, M.; Gómez-Gallego, F.; Barreiro, P.; de Mendoza, C.; Corral, O. Main differences between the first and second waves of COVID-19 in Madrid, Spain. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 105, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano, V.; de Mendoza, C.; Gómez-Gallego, F.; Corral, O.; Barreiro, P. Third wave of COVID-19 in Madrid, Spain. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendieta-Aragón, A. Effects of COVID-19 on the tourism sector in the European Union: Economic analysis for the case of Spain. Rev. Univ. Eur. 2023, 38, 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D.P.; Williams, P.; Lobo, A.; Muñoz, P.E. Cuestionario de Salud General GHQ (General Health Questionnaire). Guía Para el Usuario de las Distintas Versiones; Masson: Barcelona, Spain, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gnambs, T.; Staufenbiel, T. The structure of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12): Two meta-analytic factor analyses. Health Psychol. Rev. 2018, 12, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, A.; Åhs, J.; Åsbring, N.; Kosidou, K.; Dal, H.; Tinghög, P.; Saboonchi, F.; Dalman, C. Discriminant validity of the 12-item version of the general health questionnaire in a Swedish case-control study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2017, 71, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. The development and validation of the Comprehensive Inventory of Thriving (CIT) and the Brief Inventory of Thriving (BIT). Appl. Psychol. Health Well Being 2014, 6, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Pers. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich, J.; Tomaka, J. Measures of self-esteem. In Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes; Robinson, J.P., Shaver, P.R., Wrightsman, L.S., Eds.; Academic: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 115–160. [Google Scholar]

- Matud, M.P. Social Support Scale [Database Record]; PsycTESTS: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.W.; Dalen, J.; Wiggins, K.; Tooley, E.; Christopher, P.; Bernard, J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2008, 15, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, L.A.; Schaller, M.; Park, J.H. Perceived Vulnerability to Disease: Development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2009, 47, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, A.; Soriano, J.F.; Beleña, Á. Perceived Vulnerability to Disease Questionnaire: Factor structure, psychometric properties and gender differences. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 101, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakulak, A.; Stogianni, M.; Alonso-Arbiol, I.; Shukla, S.; Bender, M.; Yeung, V.W.L.; Jovanović, V.; Musso, P.; Scardigno, R.; Scott, R.A.; et al. The perceived vulnerability to disease scale: Cross-cultural measurement invariance and associations with fear of COVID-19 across 16 countries. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2023, 17, e12878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etheridge, B.; Spantig, L. The gender gap in mental well-being at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2022, 145, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matud, M.P. COVID-19 and mental distress and well-being among older people: A gender analysis in the first and last year of the pandemic and in the post-pandemic period. Geriatrics 2025, 10, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daly, M.; Sutin, A.R.; Robinson, E. Longitudinal changes in mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from the UK Household Longitudinal Study. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 2549–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; McDonnell, D.; Šegalo, S.; Ahmad, J.; Bennett, B. Gender inequality and health disparity amid COVID-19. Nurs. Outlook 2022, 70, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.N.; Ryan, M.K. Gender inequalities during COVID-19. Group. Process Intergroup Relat. 2021, 24, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor, L.S.; Friedman, J.; Spencer, C.N.; Cagney, J.; Arrieta, A.; E Herbert, M.; Stein, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Hon, J.; Patwardhan, V.; et al. Quantifying the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on gender equality on health, social, and economic indicators: A comprehensive review of data from March, 2020, to September, 2021. Lancet 2022, 399, 2381–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Men | Women | χ2 | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | ||

| Level of Education: | 24.47 | <0.001 | ||||

| Primary | 279 | 22.5 | 464 | 19.2 | ||

| Secondary | 440 | 35.5 | 732 | 30.2 | ||

| University | 520 | 42.0 | 1225 | 50.6 | ||

| Non-data | 5 | 12 | ||||

| Occupation: | 59.18 | <0.001 | ||||

| Employed | 1094 | 88.9 | 1890 | 78.6 | ||

| Unemployed | 104 | 8.4 | 377 | 15.7 | ||

| Other | 33 | 2.7 | 139 | 5.8 | ||

| Non-data | 13 | 27 | ||||

| Marital status: | 9.68 | 0.008 | ||||

| Never married | 263 | 21.3 | 501 | 20.7 | ||

| Married/partnered | 824 | 66.6 | 1532 | 63.3 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 150 | 12.1 | 386 | 16.0 | ||

| Non-data | 7 | 14 | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | t | p | |

| Age | 45.73 | 8.52 | 45.71 | 8.25 | 0.04 | 0.97 |

| Number of children | 1.26 | 1.10 | 1.32 | 0.99 | −1.70 | 0.09 |

| Variable | Men | Women | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Effect | F Ratio | ηp2 | |

| Psychological distress | |||||||

| Lockdown | 13.09 | 6.68 | 14.22 | 6.84 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 13.84 | 6.69 | 16.32 | 6.71 | Period | 4.34 *** | 0.009 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 12.73 | 5.81 | 15.24 | 7.51 | Gender | 38.00 *** | 0.025 |

| Post-pandemic period | 11.83 | 5.74 | 15.08 | 7.02 | Period × Gender | 1.21 | 0.002 |

| Negative feelings | |||||||

| Lockdown | 15.91 | 4.51 | 16.47 | 4.79 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 15.32 | 4.34 | 17.56 | 4.39 | Period | 1.90 | 0.004 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 15.34 | 4.12 | 16.82 | 4.50 | Gender | 55.34 *** | 0.036 |

| Post-pandemic period | 14.18 | 4.06 | 17.24 | 4.26 | Period × Gender | 4.53 ** | 0.009 |

| Positive feelings | |||||||

| Lockdown | 20.48 | 4.15 | 20.95 | 4.32 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 21.27 | 4.31 | 20.45 | 3.99 | Period | 5.66 ** | 0.011 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 21.69 | 4.62 | 21.73 | 4.34 | Gender | 2.71 | 0.002 |

| Post-pandemic period | 22.44 | 4.07 | 21.18 | 4.55 | Period × Gender | 2.61 | 0.005 |

| Affect Balance | |||||||

| Lockdown | 4.57 | 7.71 | 4.48 | 8.29 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 5.94 | 7.59 | 2.89 | 7.51 | Period | 4.02 ** | 0.008 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 6.35 | 7.82 | 4.91 | 7.99 | Gender | 26.03 *** | 0.017 |

| Post-pandemic period | 8.26 | 7.24 | 3.94 | 7.96 | Period × Gender | 4.33 ** | 0.009 |

| Thriving | |||||||

| Lockdown | 37.14 | 6.51 | 37.77 | 6.54 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 37.81 | 7.34 | 36.54 | 6.54 | Period | 1.54 | 0.003 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 38.59 | 6.56 | 37.61 | 7.23 | Gender | 4.99 * | 0.003 |

| Post-pandemic period | 38.96 | 6.58 | 37.17 | 7.30 | Period × Gender | 1.66 | 0.003 |

| Life satisfaction | |||||||

| Lockdown | 24.14 | 7.05 | 24.37 | 6.35 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 23.80 | 6.74 | 23.73 | 6.71 | Period | 0.56 | 0.001 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 23.91 | 6.64 | 23.10 | 6.98 | Gender | 5.07 * | 0.003 |

| Post-pandemic period | 25.29 | 6.36 | 22.50 | 7.25 | Period × Gender | 3.57 * | 0.007 |

| Self-esteem | |||||||

| Lockdown | 20.97 | 4.76 | 20.79 | 4.92 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 20.96 | 4.98 | 20.22 | 4.86 | Period | 0.62 | 0.001 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 21.19 | 5.26 | 20.60 | 5.37 | Gender | 7.48 ** | 0.005 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.91 | 5.05 | 20.24 | 5.59 | Period × Gender | 1.24 | 0.003 |

| Emotional Social Support | |||||||

| Lockdown | 15.33 | 4.08 | 16.31 | 4.76 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 16.23 | 5.08 | 16.23 | 4.96 | Period | 1.63 | 0.003 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 15.49 | 4.33 | 15.89 | 5.04 | Gender | 1.38 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 16.47 | 4.52 | 16.35 | 4.65 | Period × Gender | 0.77 | 0.002 |

| Instrumental Social Support | |||||||

| Lockdown | 8.28 | 3.79 | 10.95 | 3.83 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 9.78 | 3.89 | 10.51 | 3.97 | Period | 1.44 | 0.003 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 9.75 | 3.60 | 10.34 | 4.21 | Gender | 21.38 *** | 0.014 |

| Post-pandemic period | 10.21 | 3.78 | 10.32 | 4.05 | Period × Gender | 5.49 ** | 0.011 |

| Number of stressful events | |||||||

| Lockdown | 1.52 | 1.51 | 1.26 | 1.26 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 1.77 | 1.40 | 1.70 | 1.53 | Period | 14.84 *** | 0.030 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 2.17 | 1.89 | 2.38 | 1.80 | Gender | 2.04 | 0.002 |

| Post-pandemic period | 1.66 | 1.39 | 2.29 | 1.57 | Period × Gender | 5.12 ** | 0.011 |

| Variable | Men | Women | ANOVA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | Effect | F Ratio | ηp2 | |

| Psychological distress | |||||||

| Lockdown | 12.53 | 5.89 | 14.61 | 7.09 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 13.10 | 6.10 | 15.48 | 6.83 | Period | 9.05 *** | 0.012 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 12.08 | 5.54 | 13.81 | 6.37 | Gender | 40.27 *** | 0.018 |

| Post-pandemic period | 11.53 | 5.24 | 13.32 | 6.52 | Period × Gender | 0.29 | 0.000 |

| Negative feelings | |||||||

| Lockdown | 15.14 | 4.83 | 16.11 | 4.63 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 14.57 | 4.16 | 17.12 | 4.37 | Period | 3.44 * | 0.005 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 14.58 | 4.51 | 15.67 | 4.46 | Gender | 48.23 *** | 0.022 |

| Post-pandemic period | 14.46 | 4.05 | 15.85 | 4.12 | Period × Gender | 3.18 * | 0.004 |

| Positive feelings | |||||||

| Lockdown | 20.48 | 3.94 | 20.75 | 4.39 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 20.67 | 3.88 | 19.84 | 4.09 | Period | 13.15 *** | 0.018 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 21.22 | 4.64 | 21.44 | 4.20 | Gender | 0.74 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.87 | 3.68 | 21.50 | 4.32 | Period × Gender | 1.75 | 0.002 |

| Affect Balance | |||||||

| Lockdown | 5.34 | 7.88 | 4.65 | 8.33 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 6.10 | 7.16 | 2.71 | 7.50 | Period | 9.03 *** | 0.012 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 6.63 | 8.14 | 5.77 | 7.78 | Gender | 19.56 *** | 0.009 |

| Post-pandemic period | 7.41 | 7.02 | 5.66 | 7.58 | Period × Gender | 2.90 * | 0.004 |

| Thriving | |||||||

| Lockdown | 38.01 | 5.45 | 37.45 | 6.71 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 36.99 | 6.09 | 36.03 | 6.44 | Period | 8.08 *** | 0.011 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 37.68 | 5.78 | 37.67 | 6.28 | Gender | 3.72 | 0.002 |

| Post-pandemic period | 38.72 | 5.96 | 37.86 | 6.41 | Period × Gender | 0.60 | 0.001 |

| Life satisfaction | |||||||

| Lockdown | 23.64 | 6.88 | 23.62 | 6.91 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 23.67 | 6.67 | 22.66 | 6.66 | Period | 3.55 * | 0.005 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 24.05 | 6.38 | 23.85 | 6.59 | Gender | 2.73 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 24.87 | 5.92 | 23.93 | 6.80 | Period × Gender | 0.61 | 0.001 |

| Self-esteem | |||||||

| Lockdown | 21.97 | 4.23 | 21.10 | 4.97 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 21.01 | 4.19 | 20.39 | 4.45 | Period | 2.76 * | 0.004 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 21.23 | 4.24 | 21.30 | 5.00 | Gender | 3.22 | 0.001 |

| Post-pandemic period | 21.52 | 4.45 | 21.26 | 5.09 | Period × Gender | 0.72 | 0.001 |

| Emotional Social Support | |||||||

| Lockdown | 14.82 | 4.61 | 14.79 | 5.06 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 15.40 | 4.95 | 15.36 | 4.95 | Period | 1.27 | 0.002 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 14.82 | 5.24 | 15.30 | 5.10 | Gender | 0.34 | 0.000 |

| Post-pandemic period | 15.36 | 4.72 | 15.51 | 5.01 | Period × Gender | 0.28 | 0.000 |

| Instrumental Social Support | |||||||

| Lockdown | 8.14 | 3.71 | 9.06 | 4.06 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 8.81 | 4.04 | 9.57 | 4.01 | Period | 4.31 ** | 0.006 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 8.60 | 4.22 | 9.45 | 4.21 | Gender | 16.16 *** | 0.007 |

| Post-pandemic period | 9.26 | 4.05 | 9.99 | 4.07 | Period × Gender | 0.04 | 0.000 |

| Number of stressful events | |||||||

| Lockdown | 1.15 | 1.27 | 1.46 | 1.42 | |||

| Second and Third pandemic waves | 1.38 | 1.48 | 1.52 | 1.47 | Period | 19.41 *** | 0.027 |

| Last year of the pandemic | 2.01 | 1.65 | 2.05 | 1.71 | Gender | 5.58 * | 0.003 |

| Post-pandemic period | 1.78 | 1.52 | 2.02 | 1.52 | Period × Gender | 0.58 | 0.001 |

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | n | % | n | % | Χ2 | p |

| Established adulthood (30 to 45 years) | ||||||

| Loss of employment | 27 | 16.6 | 34 | 13.9 | 0.53 | 0.466 |

| Financial problems | 41 | 25.0 | 70 | 28.9 | 0.76 | 0.384 |

| Major disagreements with partner a | 18 | 18.4 | 51 | 34.0 | 7.21 | 0.007 |

| Major disagreements with family | 24 | 14.6 | 66 | 27.3 | 9.05 | 0.003 |

| Illness of family members or loved ones | 80 | 48.8 | 141 | 58.0 | 3.37 | 0.066 |

| Death of one or more family members or loved ones | 49 | 29.9 | 86 | 35.4 | 1.34 | 0.247 |

| Own illness | 14 | 8.6 | 62 | 25.5 | 18.37 | <0.001 |

| Other events | 1 | 0.6 | 15 | 6.1 | 7.98 | 0.005 |

| Midlife (45 to 59 years) | ||||||

| Loss of employment | 29 | 9.6 | 33 | 9.0 | 0.06 | 0.804 |

| Financial problems | 50 | 16.6 | 93 | 25.5 | 7.92 | 0.005 |

| Major disagreements with partner a | 48 | 20.9 | 36 | 16.3 | 1.56 | 0.212 |

| Major disagreements with family | 38 | 12.6 | 70 | 19.2 | 5.29 | 0.021 |

| Illness of family members or loved ones | 144 | 47.7 | 206 | 56.9 | 5.62 | 0.018 |

| Death of one or more family members or loved ones | 123 | 40.7 | 136 | 37.4 | 0.79 | 0.375 |

| Own illness | 65 | 21.7 | 101 | 27.9 | 3.93 | 0.065 |

| Other events | 12 | 4.0 | 32 | 8.8 | 6.16 | 0.013 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Established adulthood | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.11 | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.18 | −0.03 | −0.43 | −0.04 | −0.73 |

| Number of children | −0.08 | −1.01 | −0.03 | −0.38 | −0.03 | −0.47 | 0.02 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.66 |

| Education | −0.14 | −2.04 * | −0.13 | −2.02 * | −0.08 | −1.22 | −0.05 | −0.86 | −0.02 | −0.45 |

| Married/partnered | 0.01 | 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.64 | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.26 | 0.03 | 0.61 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.26 | 3.96 *** | 0.20 | 3.11 ** | 0.12 | 2.13 * | 0.06 | 1.03 | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.34 | 5.32 *** | 0.29 | 5.06 *** | 0.19 | 3.52 ** | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.42 | −7.48 *** | −0.22 | −3.79 *** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.34 | 5.16 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | −0.14 | −1.69 | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | −0.04 | −0.45 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.19 | 0.36 | 0.49 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.47 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.02 | 0.07 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.13 *** | |||||

| Midlife women | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.02 | −0.33 | −0.02 | −0.45 | −0.02 | −0.39 | −0.03 | −0.76 | −0.03 | −0.70 |

| Number of children | −0.07 | −1.17 | −0.06 | −0.96 | −0.06 | −1.06 | −0.03 | −0.52 | −0.01 | −0.12 |

| Education | −0.08 | −1.41 | −0.05 | −0.95 | −0.02 | −0.32 | 0.05 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 1.38 |

| Married/partnered | −0.07 | −1.20 | −0.08 | −1.40 | −0.03 | −0.57 | −0.05 | −1.17 | −0.06 | −1.55 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.28 | 5.32 *** | 0.23 | 4.66 *** | 0.11 | 2.45 * | 1.00 | 2.49 * | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.38 | 7.82 *** | 0.34 | 7.60 *** | 0.27 | 6.56 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.41 | −8.94 *** | −0.25 | −5.58 *** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.37 | −8.27 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | −0.11 | −1.44 | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | −0.02 | −0.28 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.52 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.51 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.02 | 0.08 *** | 0.14 *** | 0.15 *** | 0.14 *** | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Established adulthood | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.02 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.05 | 0.77 |

| Number of children | 0.04 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.45 | 0.07 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.06 | 0.84 |

| Education | −0.05 | −0.60 | −0.05 | −0.55 | −0.03 | −0.42 | −0.02 | −0.34 | −0.01 | −0.19 |

| Married/partnered | −0.23 | −2.67 ** | −0.23 | −2.62 * | −0.27 | −3.28 ** | −0.25 | −3.49 ** | −0.19 | 2.82 ** |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.03 | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.55 | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.32 | 4.15 *** | 0.24 | 3.50 ** | 0.15 | 2.34 * | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.46 | 6.71 *** | −0.15 | −1.92 | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.45 | −5.17 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | −0.24 | −2.24 * | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | 0.15 | 1.50 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.36 | 0.51 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.48 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.10 *** | 0.20 *** | 0.15 *** | |||||

| Midlife | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.02 | −0.41 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.19 | −0.01 | −0.17 |

| Number of children | 0.05 | 0.86 | 0.07 | 1.17 | 0.04 | 0.65 | 0.04 | 0.84 | 0.04 | 0.79 |

| Education | −0.07 | −1.11 | −0.05 | −0.92 | −0.04 | −0.78 | −0.02 | −0.36 | −0.03 | −0.62 |

| Married/partnered | −0.18 | −3.07 ** | −0.18 | −3.10 ** | −0.15 | −2.71 ** | −0.11 | −2.20 * | −0.07 | −1.39 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.28 | 4.89 *** | 0.23 | 4.20 *** | 0.12 | 2.27 * | 0.10 | 1.93 | ||

| Number of stressful events | 0.32 | 5.88 *** | 0.29 | 5.65 *** | 0.24 | 4.84 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | −0.31 | −5.75 *** | −0.17 | −2.99 ** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | −0.30 | −5.43 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | 0.04 | 0.55 | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | −0.18 | −2.49 * | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.29 | 0.40 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.38 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.04 * | 0.07 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.11 *** | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Established adulthood | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.11 | −1.61 | −0.10 | −1.55 | −0.09 | −1.46 | −0.08 | −1.43 | −0.06 | −1.48 |

| Number of children | 0.22 | 2.91 ** | 0.16 | 2.23 * | 0.17 | 2.40 * | 0.12 | 1.89 | 0.09 | 1.86 |

| Education | 0.18 | 2.69 ** | 0.17 | 2.71 ** | 0.12 | 2.01 * | 0.09 | 1.74 | 0.06 | 1.37 |

| Married/partnered | −0.01 | −0.17 | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.01 | 0.19 | −0.01 | −0.11 | −0.03 | −0.78 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | −0.30 | −4.70 *** | −0.25 | −3.93 *** | −0.17 | −3.00 ** | −0.07 | −1.65 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.29 | −4.70 *** | −0.24 | −4.40 *** | −0.10 | −2.33 * | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.45 | 8.21 *** | 0.16 | 3.33 ** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.50 | 9.53 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | 0.22 | 3.20 ** | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | 0.02 | 0.32 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.41 | 0.68 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.66 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.06 ** | 0.09 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.27 *** | |||||

| Midlife | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.60 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.04 | 1.18 |

| Number of children | 0.15 | 2.60 * | 0.14 | 2.47 * | 0.14 | 2.61 ** | 0.11 | 2.24 * | 0.08 | 2.17* |

| Education | 0.15 | 2.70 ** | 0.13 | 2.37 * | 0.10 | 1.92 | 0.03 | 0.60 | 0.02 | 0.42 |

| Married/partnered | 0.06 | 1.04 | 0.06 | 1.18 | 0.02 | 0.47 | 0.05 | 1.14 | 0.06 | 1.68 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | −0.20 | −3.90 *** | −0.16 | −3.21 ** | −0.03 | −0.69 | −0.02 | −0.51 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.32 | −6.35 *** | −0.27 | −6.03 *** | −0.16 | −4.63 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.47 | 10.04 *** | 0.24 | 6.24 *** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.47 | 12.12 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | 0.17 | 2.68 ** | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | 0.06 | 0.93 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.37 | 0.64 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.36 | 0.63 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.05 ** | 0.04 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.27 *** | |||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value | β | t-Value |

| Established adulthood | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.40 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Number of children | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.85 |

| Education | 0.12 | 1.38 | 0.12 | 1.45 | 0.11 | 1.37 | 0.10 | 1.51 | 0.07 | 1.36 |

| Married/partnered | 0.11 | 1.28 | 0.12 | 1.33 | 0.16 | 1.90 | 0.14 | 2.03 * | 0.05 | 0.95 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | 0.05 | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.53 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.04 | 0.71 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.32 | −4.00 *** | −0.22 | −3.35 ** | −0.07 | −1.40 | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.57 | 8.97 *** | 0.18 | 2.84 ** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.52 | 7.35 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | 0.07 | 0.83 | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | 0.15 | 1.77 | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.67 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.42 | 0.65 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.10 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.23 *** | |||||

| Midlife | ||||||||||

| Age | −0.03 | −0.46 | −0.03 | −0.60 | −0.05 | −0.82 | −0.06 | −1.11 | −0.02 | −0.62 |

| Number of children | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.02 | 0.39 |

| Education | 0.09 | 1.59 | 0.09 | 1.48 | 0.08 | 1.38 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.07 | 1.85 |

| Married/partnered | 0.23 | 3.94 *** | 0.23 | 3.93 *** | 0.20 | 3.61 *** | 0.16 | 3.06 ** | 0.06 | 1.36 |

| Perceived vulnerability to infection | −0.15 | −2.60 * | −0.11 | −1.89 | 0.04 | 0.75 | 0.08 | 1.86 | ||

| Number of stressful events | −0.28 | −5.02 *** | −0.24 | −4.80 *** | −0.15 | −3.66 *** | ||||

| Stress resilience | 0.44 | 8.21 *** | 0.19 | 4.06 *** | ||||||

| Self-esteem | 0.46 | 9.96 *** | ||||||||

| Emotional social support | 0.15 | 2.31 * | ||||||||

| Instrumental social support | 0.14 | 2.40 * | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.32 | 0.60 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.31 | 0.58 | |||||

| R2 Change | 0.06 ** | 0.02 * | 0.08 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.28 *** | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matud, M.P.; Medina, L.; Ibañez, I.; Pino, M.-J.d. Mental Health Among Spanish Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period: A Gender Analysis. Medicina 2025, 61, 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101734

Matud MP, Medina L, Ibañez I, Pino M-Jd. Mental Health Among Spanish Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period: A Gender Analysis. Medicina. 2025; 61(10):1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101734

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatud, M. Pilar, Lorena Medina, Ignacio Ibañez, and Maria-José del Pino. 2025. "Mental Health Among Spanish Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period: A Gender Analysis" Medicina 61, no. 10: 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101734

APA StyleMatud, M. P., Medina, L., Ibañez, I., & Pino, M.-J. d. (2025). Mental Health Among Spanish Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic and in the Post-Pandemic Period: A Gender Analysis. Medicina, 61(10), 1734. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61101734